A Guest Policy Research Commentary

October 2016

As the November presidential election inches closer, many organizations are putting the finishing touches on their “transition” plans—their vision and recommendations for the next administration. This, therefore, is an opportune time to re-examine the assumptions and the outcomes of current federal policy on homelessness. A review of available evidence makes clear that in order to address homelessness now and prevent it in the future, we must focus on the complex realities and comprehensive needs of homeless children and youth—by adopting an honest definition of homelessness, retooling homeless assistance with child and youth development at the forefront, and ensuring that early care, education, and services are linked directly to any family homelessness housing initiatives.

Evaluating the Chronic Homelessness Priority

The Obama administration’s strategic federal plan on homelessness, “Opening Doors,” established the national goal of ending chronic and veteran homelessness by 2015.1 That goal, which extended the (George W.) Bush administration’s target of ending chronic homelessness by 2012, has since been pushed back two more times, to 2016 and then 2017—despite the fact that the federal government has focused its energy and funding overwhelmingly on chronically homeless adults since 2004.

In its quest to end chronic homelessness, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has changed the way it scores local communities’ applications for homeless assistance funding and has used its formidable administrative and regulatory power to force communities to maximize services for chronically homeless people throughout the country, regardless of local circumstances and needs. An examination of ten years of this approach reveals flawed economic logic, a failure to “end” chronic homelessness today, and a paradigm that might actually sustain chronic homelessness into the future.

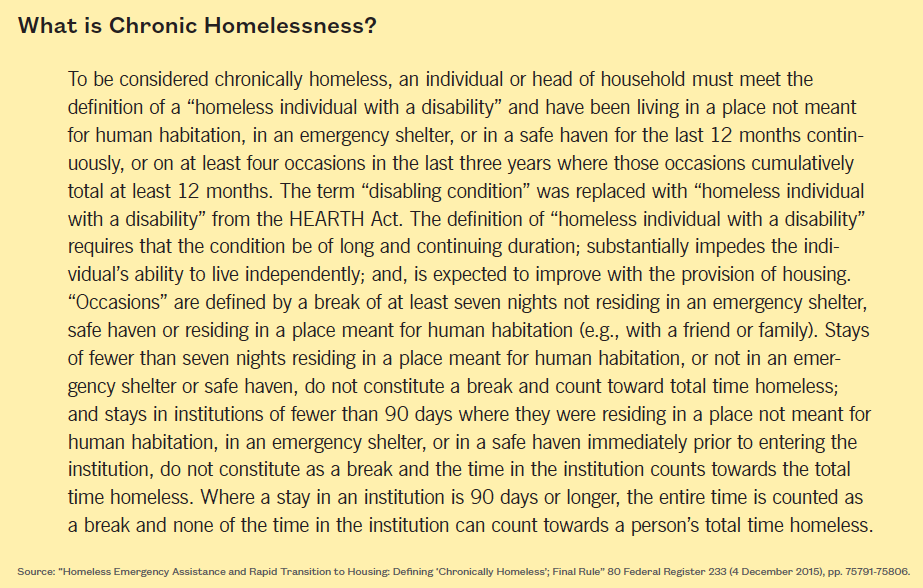

The problems with the chronic homelessness priority begin with how chronic homelessness is defined. What is meant by “chronically homeless?” HUD now considers an individual or head of household to be chronically homeless only if he or she meets the definition of a “homeless individual with a disability” and has been living in a place not meant for human habitation, in an emergency shelter, or in a safe haven for the last 12 months continuously, or on at least four occasions in the last three years where those occasions cumulatively total at least 12 months.2 Last year HUD promulgated regulations to further restrict the definition of what constitutes chronic homelessness, adding layers to an already complex definition (see the detailed definition in sidebar, page 2). The narrowness of this definition excludes many homeless single adults, and even more parents and children.

The economic justification for the chronic homelessness priority is equally flawed. The original argument was that targeting resources to chronically homeless people will “free up” resources to serve other homeless populations—eventually. Yet, after more than a decade of these policies, neither HUD nor the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) has freed up resources for other homeless populations. They have not explained when or how any savings that might someday materialize will be passed on to other homeless populations. To the contrary, both agencies continue to fight efforts to allow local communities to prioritize other populations with HUD homeless assistance, even when those communities repeatedly identify other, more urgent needs.

The “trickle-down” feature of the chronic homelessness priority is also absent on the ground. Programs for homeless families have not seen an increase in resources as a result of the supposed decrease in chronic homelessness. In fact, many of these programs have lost funding as a direct result of HUD’s emphasis on chronic homelessness. This loss is compounded by the fact that many private foundations and local and state governments have followed the federally-established priority on chronic homelessness. HUD’s Point-in-Time counts, which exclude large segments of the homeless population, prop up these misguided federal policies, and encourage redirection of private and local funding.

Despite the failure of the trickle-down economic justification for the focus on chronic homelessness, one still might accept the campaign to end chronic homelessness if it effectively addressed the plight of chronically homeless people. But what about those triumphant headlines trumpeting the end of chronic homelessness in various communities? Is the end of chronic homelessness in sight?

Certainly, some communities have seen significant reductions in the counts of chronically homeless people, although HUD’s creative definitions may well have contributed to the reported successes. In addition to the narrowing of the definition of chronic homelessness mentioned previously, HUD also invented the term “functional zero.”3 This Orwellian term does not mean that there are no more chronically homeless people in the communities that have reached “functional zero.” Instead, it means that the availability of resources in the community exceeds the size of the population needing the resources. Whether homeless people use those resources or are successful with them is not relevant. Under “functional zero,” people remain chronically homeless on the streets even after their communities have “ended” chronic homelessness.

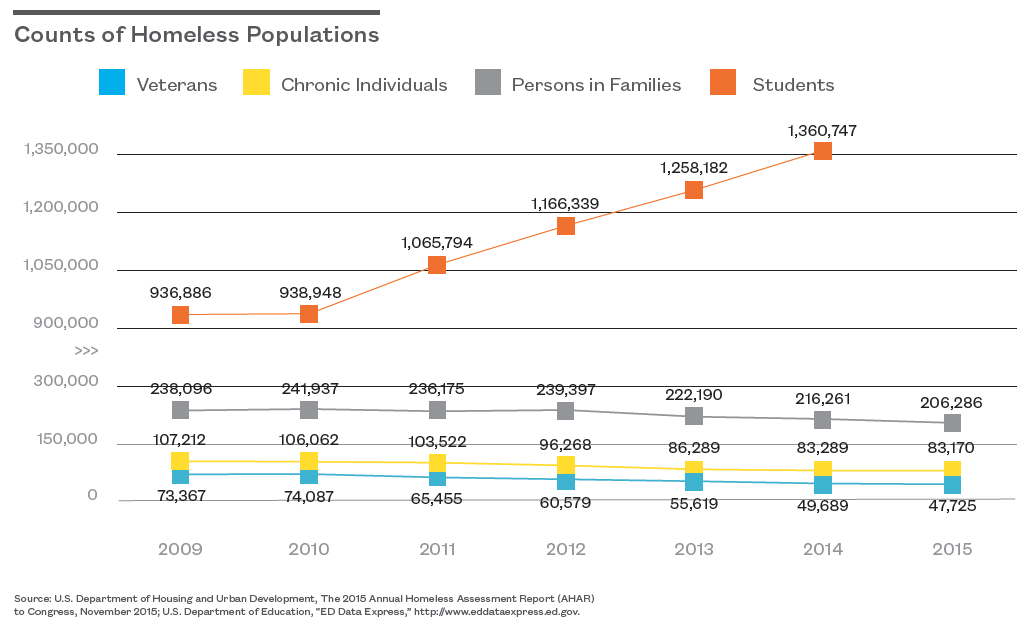

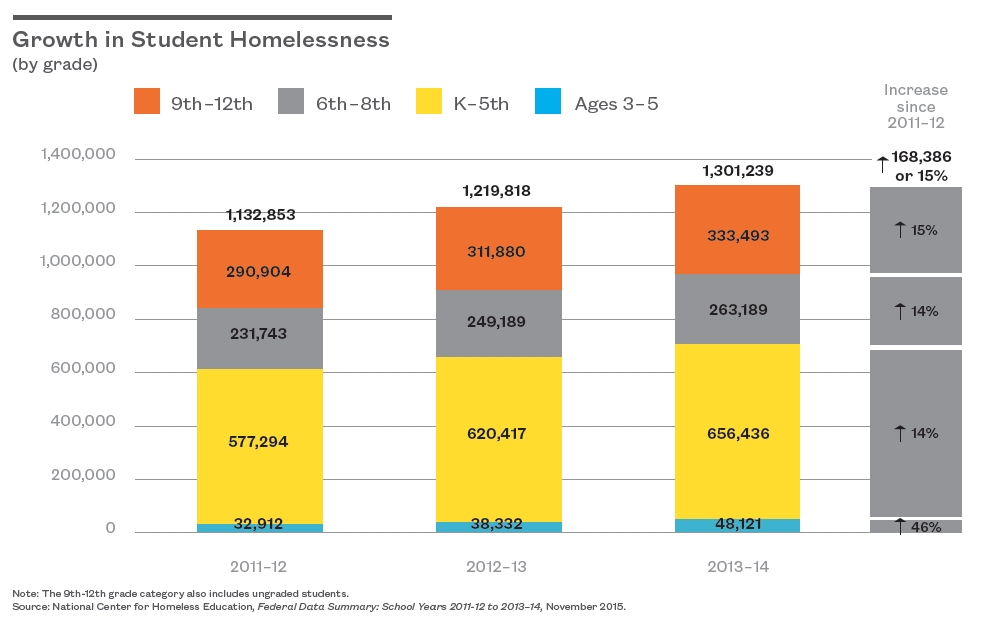

Meanwhile, other headlines on homelessness describe our national predicament more clearly and forthrightly. Family homelessness has reached record levels in many major cities, leading some officials to declare a state of emergency. Public schools are yet another barometer of this disastrous state of affairs: schools identified 1,301,239 homeless children and youth in 2013–14, a seven percent increase over the previous year, and a 100 percent increase since the 2006–07 school year.4 The number of young homeless children enrolled in Head Start increased by 92 percent over approximately the same period.5

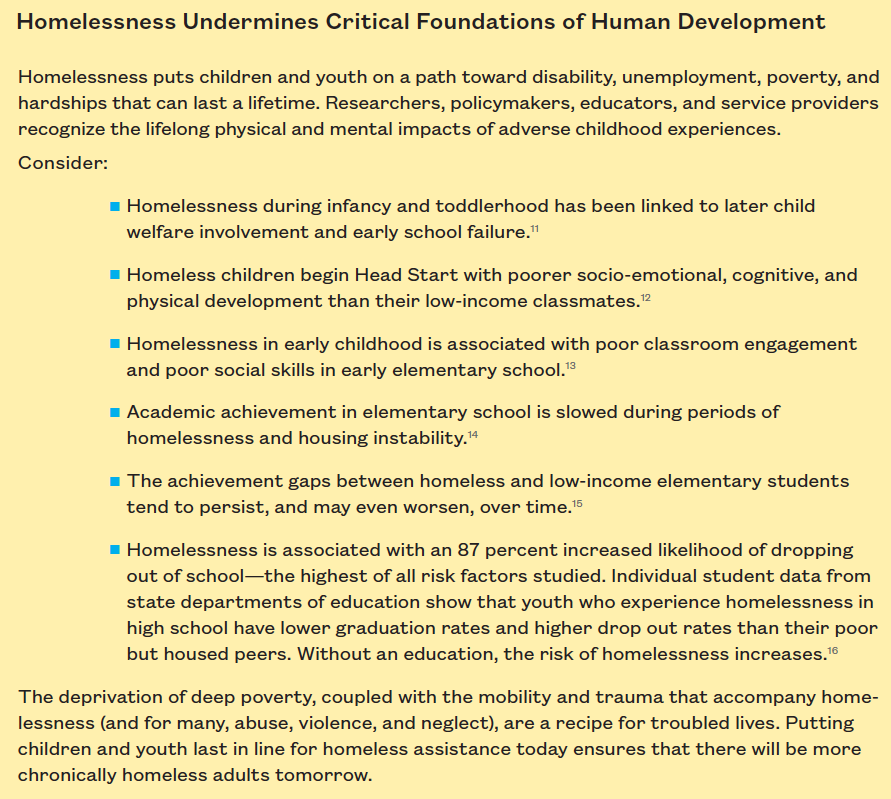

As some types of homelessness are declared to be dwindling while others explode, the chronic homelessness priority reveals another, more fundamental weakness. Targeting assistance to people who currently meet the definition of chronically homeless does nothing to prevent chronic homelessness from happening in the first place. While some of today’s chronically homeless adults are receiving supportive housing to end their homelessness, by relegating children and youth to the end of the queue in the nation’s plan to end homelessness, and failing to promote assistance that meets their unique needs, we ensure a continuous flow of homeless young people falling through the cracks, many to become “chronically homeless” themselves as the system continues to fail them over time.

‘Ending’ Family Homelessness by 2020?

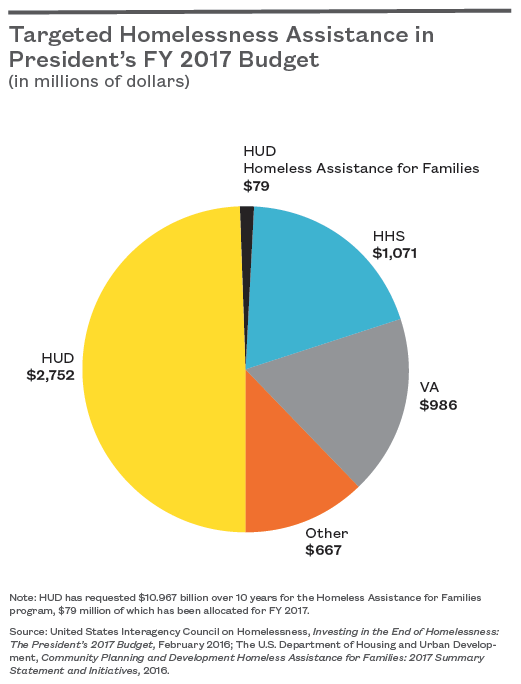

As a secondary goal, the administration’s “Opening Doors” plan proposed to end youth and family homelessness by 2020.6 Yet, it was not until this year—the final year of the Obama administration and just four years before the deadline to end family homelessness—that HUD’s budget called for any focused effort on family homelessness. This came in the form of an $11 billion request in mandatory funding over ten years for housing assistance (mostly Housing Choice Vouchers, plus new funding for rapid re-housing) for families who meet HUD’s limited definition of homelessness.7

HUD’s FY 2017 family homelessness proposal is regarded by most observers as dead on arrival, due to the size of the funding request, the limited legislative calendar, and the tense fiscal and political budget climate. The proposal therefore is being positioned as the centerpiece of family homelessness policy for the next administration. As such, it merits careful consideration.

The claim that HUD’s proposal will “end family homelessness” is based on an assumption that family homelessness is primarily, even exclusively, a problem of housing affordability, and can be remedied by the provision of short- or longer-term housing assistance. HUD supports this claim with preliminary findings from the Family Options Study, which found that families offered a housing voucher experienced significantly less homelessness, fewer moves, and better outcomes than families assigned to other interventions.8 Yet questions have been raised about the methodology and design of the Family Options Study, casting doubt on whether its preliminary findings are as conclusive as stated.9 At a minimum, the study demands more scrutiny before serving as the justification for a massive investment that purports to “end” family homelessness in the United States.

Framing family homelessness as primarily a housing problem appears to be rooted more in wishful thinking and ideology than in the reality of homelessness experienced by parents and children—a complex problem caused by deep poverty, and exacerbated by lack of education, lack of child care, lack of employment options, and a severe shortage of affordable housing.

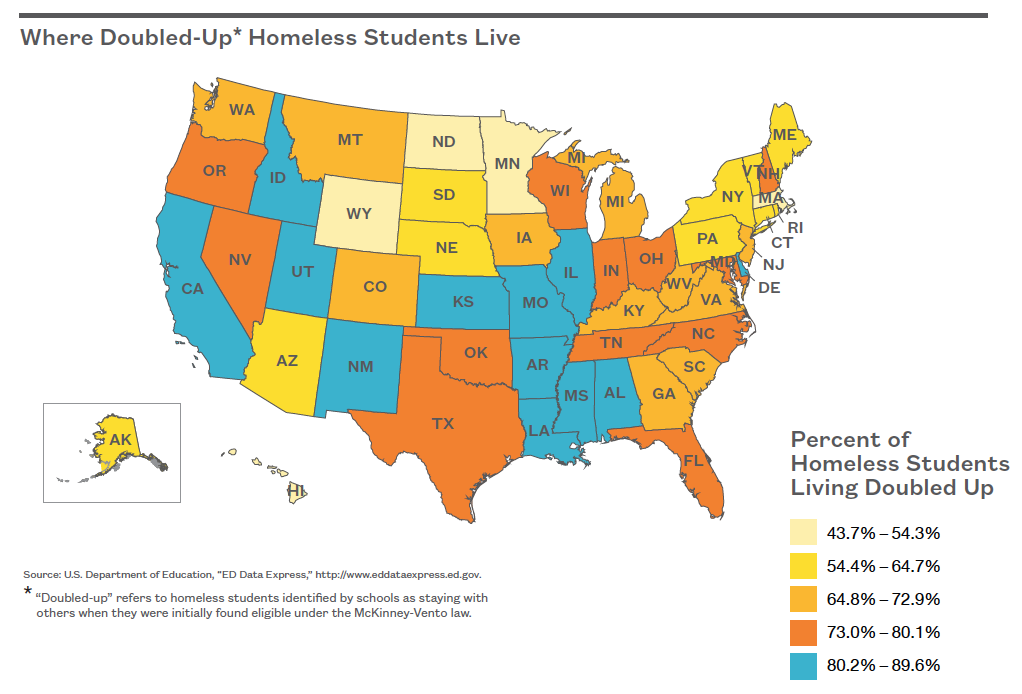

But there is another equally significant problem: putting aside its dubious premises, HUD’s family homelessness proposal is limited to families who meet HUD’s restrictive definition of homelessness—those in shelters or in unsheltered locations. It therefore excludes over 80 percent of the homeless children and youth who are identified by public schools and early care programs, but who do not meet HUD’s definition because there are no shelters, shelters are full, or shelters restrict eligibility.10 These children and their parents have no other option but to stay in motels or temporarily with other people in crowded, precarious, and often unsafe situations that jeopardize children’s health, safety, and development. HUD’s steadfast refusal to acknowledge that these families, children, and youth are homeless and that homelessness fundamentally looks different for families, children, and youth bodes poorly for any hope of ending family homelessness, chronic homelessness, or any other type of homelessness. Even if HUD’s family homelessness proposal were enacted tomorrow and all the families currently in homeless shelters were provided housing, these same shelters would be full the next day with these “new” homeless families in need of help.

Looking to the Future

What is needed now, in this time of reflection and transition, is a new paradigm that connects cause and consequence throughout the human lifespan— from before birth through adulthood. This new paradigm must reject the grossly mistaken assumption that homeless parents and children simply need housing—and that they are less vulnerable, easier to serve, and have fewer disabling conditions simply because they are not visible on the streets. We must contend with the complexity of family homelessness—its many layers, causes, and impacts.

To do so, we must recognize that, while housing is a critical need of homeless families, it is not their only need: housing is necessary, but not sufficient. Nor are “mainstream services” for homeless parents and children the panacea claimed by some advocates. Mainstream services are often inaccessible, not only due to lack of funding, but because homelessness itself creates barriers to accessing them: high mobility, lack of transportation, missing documentation, and lack of outreach all create barriers to accessing child care, early childhood programs, food, employment, education, and health care. We are setting families up to fail if these barriers are not addressed with the same vigor that the federal government demanded of communities in assisting chronically homeless adults. We must acknowledge that homelessness presents qualitatively different perils for children and youth, necessitating different standards for eligibility and different standards for assessing risk. Their brains, bodies, and spirits are developing now (see sidebar, page 6). They cannot wait any longer to become a priority, or for solutions that meet their unique and comprehensive needs.

What should drive the vision of the next administration? We propose a realistic, two-generational approach to family and youth homelessness, grounded in the interconnected and equally vital roles of housing, education, early care, and services.

Indeed, without early care and education, the prospect of affording any kind of housing as an adult is slim, making today’s homeless children more likely to become tomorrow’s homeless adults. A two-generational approach to ending family homelessness calls for full engagement of child care, early learning programs, schools, and other children’s services as essential and equal partners with housing agencies and homeless service providers. In addition, homeless assistance services, program design, outcomes, and policies must be built around the specific and unique needs of children and youth as clients—with needs equal to, but separate from and different than, the needs of their parents. While these measures are ultimately the best long-term approach to addressing both single adult and family homelessness, they cannot be packaged neatly into a 10-year-plan, “ending” homelessness by 2020, or in other marketing campaigns masquerading as public policy.

In sum, if the national dialogue and outline for action on family homelessness is limited to initiatives that provide housing for a narrowly and artificially defined segment of homeless children, youth, and families (that is, only those who meet HUD’s outdated definition of homelessness), minimize the role of essential services (including education), and ignore or treat as an after-thought children’s unique developmental needs, we will be generating poverty and homelessness for the foreseeable future. We will not truly end chronic homelessness, or any other kind of homelessness, until the complex realities and comprehensive needs of homeless children and youth take a front seat in federal homelessness policy. Only then will we see true cost savings and real homelessness prevention, albeit with a longer time frame than a presidential administration.

Barbara Duffield is the Director of Policy and Programs for the National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth (NAEHCY).

Updated from the Summer 2016 issue of UNCENSORED, vol 7.2.