Executive Summary

Education provides the best chance for children to break the cycle of poverty and homelessness. Not only is academic achievement crucial for life outcomes, but the social and emotional development that happens in school is vital as well. The connections created in the classroom are even more critical for any child who has experienced housing instability and homelessness.

More than 140,000 children attending New York City public schools have experienced homelessness within the past six years. Together, these children would form a city larger than White Plains and New Rochelle combined, with roughly the same population size as Syracuse, New York. Given the prevalence of homelessness among school-age students, educators and policymakers need to understand the educational challenges that students experiencing homelessness face, and the opportunities that exist to help students in temporary housing succeed.

Homelessness is more than a lack of housing. For the more than 140,000 students in New York City who have been homeless, the impact of housing instability is all too real. These children are not only struggling with maintaining a place to sleep, but also attending school, succeeding academically, and accessing supports for their additional educational and behavioral needs. Improving student achievement for homeless and formerly homeless students is not as simple as addressing a student’s housing, but knowing more about homeless students’ experiences in school is an important step to addressing their unique support needs.

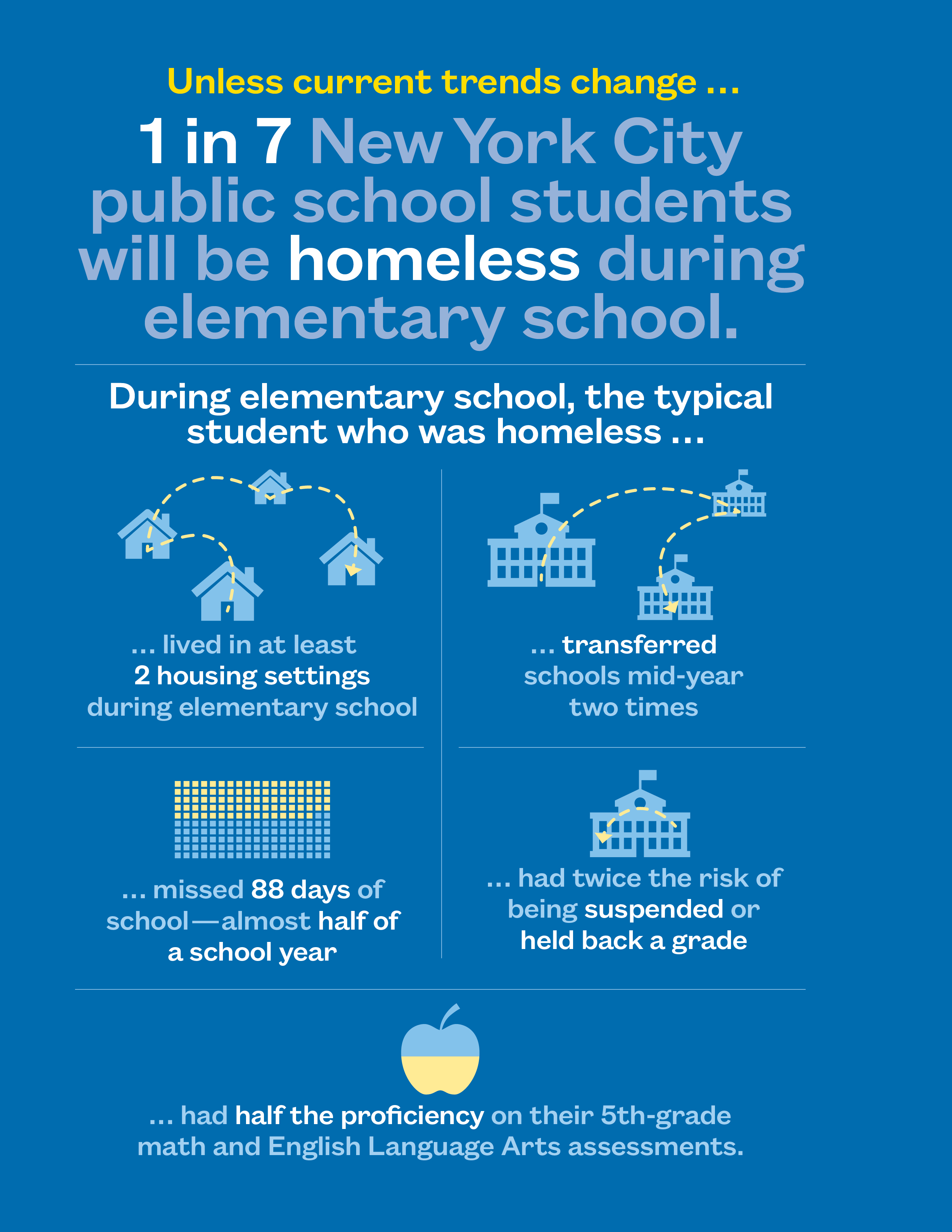

The 2017 Atlas of Student Homelessness in New York City builds on the 2016 Atlas of Student Homelessness, providing a more in-depth look at the educational outcomes of homeless students. Using a six-year cohort of elementary students, this publication highlights the educational risks faced by the one in seven children who will experience housing instability by the end of elementary school if current trends do not change. This publication also reveals the different educational risks faced by students living in shelters compared to those living doubled up or in other temporary situations, as well as outcomes of formerly homeless students, who experience continued instability in the classroom.

What’s New?

- The number of homeless students in NYC public schools increased by almost 33,000 students—a 50 percent jump— in six years.

- If current trends continue, more than one out of seven NYC public school students will experience homelessness at least once by the time they reach fifth grade.

- Despite improvement in academic outcomes between SY 2010–11 and SY 2015–16, gaps by housing status and type of homelessness persist. Students in shelter achieve proficiency on 3rd–8th grade math State assessments at just half the rate of homeless students living doubled up.

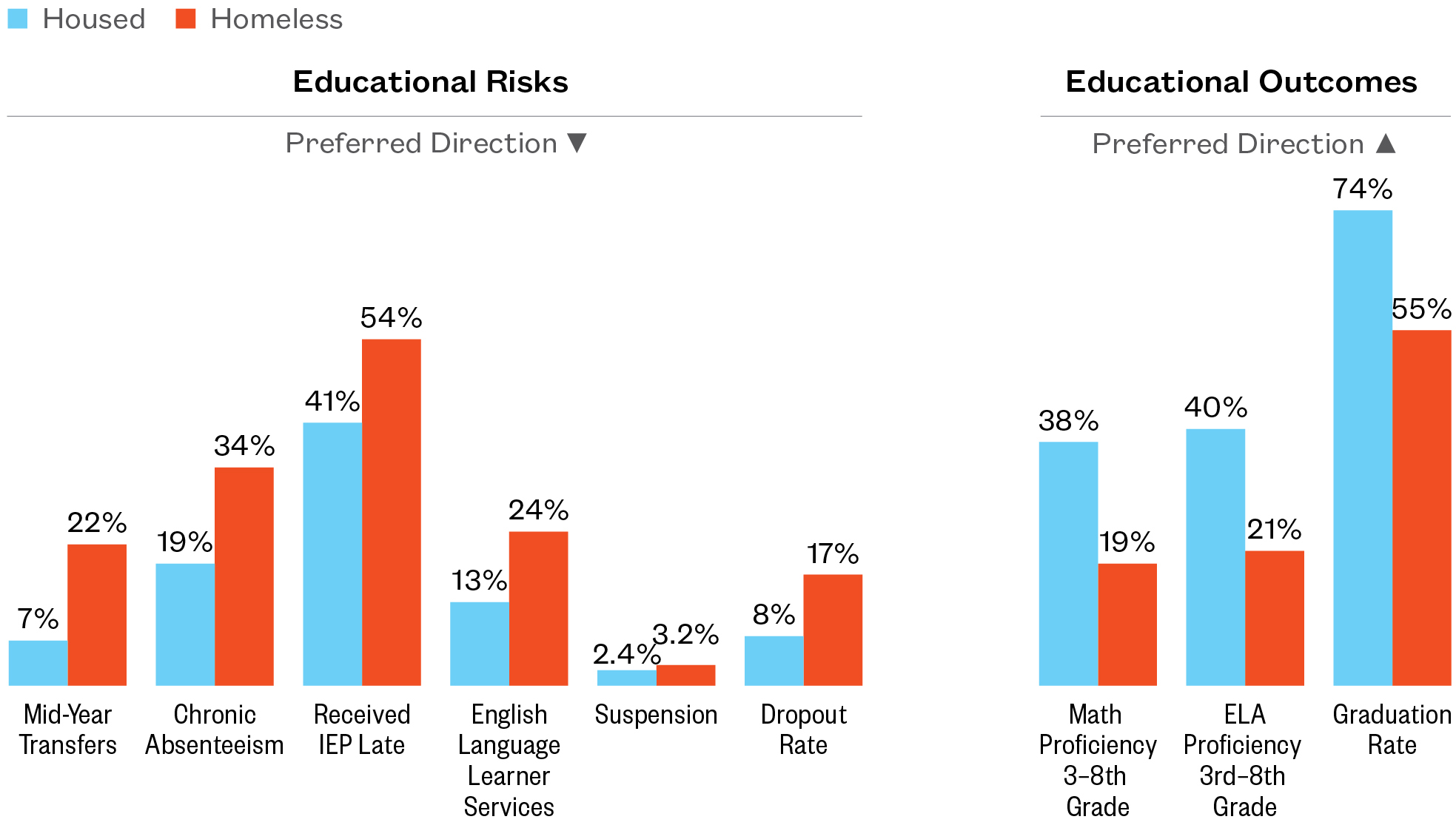

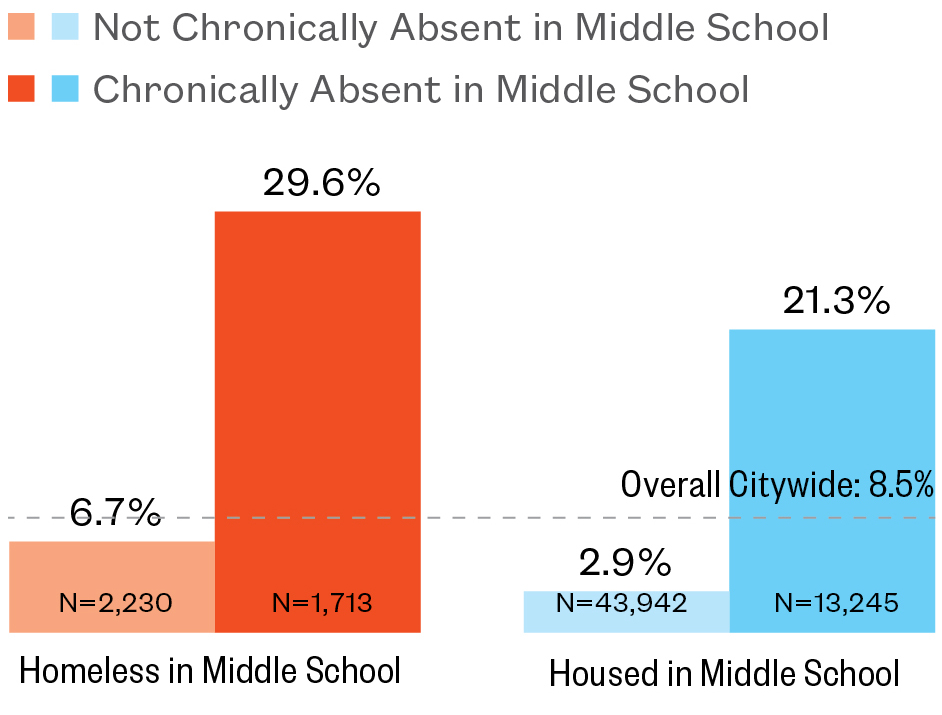

- Even after moving into stable housing, students with a history of homelessness experience lasting effects of instability, with 1.5 times the chronic absenteeism and mid-year transfer rates of their low-income peers who had always been housed.

Policy Considerations

- The way that available data are used must change in order to effectively improve educational outcomes for homeless students. Schools, service providers, policymakers, and elected officials need to look at the type of homelessness students experience, since gaps between sheltered and other homeless students are persistent.

- Additional supports in schools like IEP and ELL programs must take students’ housing status into consideration when delivering services. Students who have been homeless are more likely to need additional educational and language learning supports, but are less likely to receive those supports in a timely and effective manner. IEP and ELL programs must consider the unstable housing situations that many students are facing and the unique challenges placed on their attendance and school stability.

- It is critical to recognize that the effects of homelessness last beyond the experience itself. Available data that show whether students have a history of homelessness should be made more accessible to teachers and administrators, and can help ensure that supports exist both for students who are currently living in unstable housing as well as those who have been homeless in the past.

- A student’s record of homelessness is only captured roughly once per year. This fails to account for students who experienced homelessness later in the year, and also does not provide a full picture of the students’ history of homelessness to teachers and school administrators.

Key Citywide Findings

- The number of homeless students in NYC public schools jumped by 20% in just one year, reaching close to 100,000 in SY 2015–16.

- An average of nine percent of New York City public school students were homeless in one year (SY 2015–16).

- In addition to the nine percent of students homeless in SY 2015–16, another four percent were currently housed but had experienced homelessness at some point since SY 2010–11 (formerly homeless).

- The City has succeeded in increasing pre-K enrollment among homeless children, with a 17% increase from SY 2014–15 to SY 2015–16.

- On average, 6.6% of students in New York City charter schools were homeless in SY 2015–16—three points lower than the rate of students experiencing homelessness in public schools (9.3%).

- Students who had a history of homelessness but were housed in SY 2015–16 (formerly homeless) were still facing instability at school. Almost a third were chronically absent and 13% transferred schools mid-year compared to 19% and 7% among housed students citywide.

- Absenteeism places students at risk of not only falling behind academically, but also having their additional support needs be identified later. Homeless students who were absent 40 or more days in Kindergarten had a 12-point higher rate of late IEP identification compared to their homeless peers with 0–4 absences.

- One in every six English Language Learner (ELL) students was homeless in SY 2015–16. The majority (82%) of homeless students with ELL needs were living doubled up.

- Homeless students were not only more likely to have ELL needs, but they were also more likely to be designated as ELL for longer than their housed peers who were both low income and not low income. More than 40% of homeless ELL students still had ELL needs after six years compared to one-third of low-income housed students and only 4% of non-low-income housed students.

- Amidst citywide policy and curricula changes over time, achievement gaps by housing status persisted. Homeless students scored proficient at roughly half the rate of housed students overall on State English Language Arts (ELA) assessments (21% to 40% in SY 2015–16).

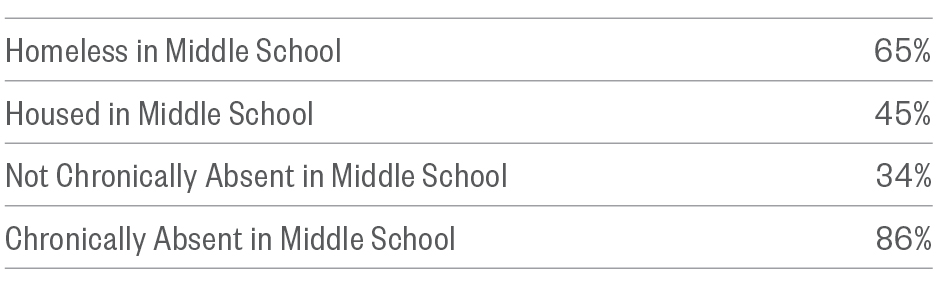

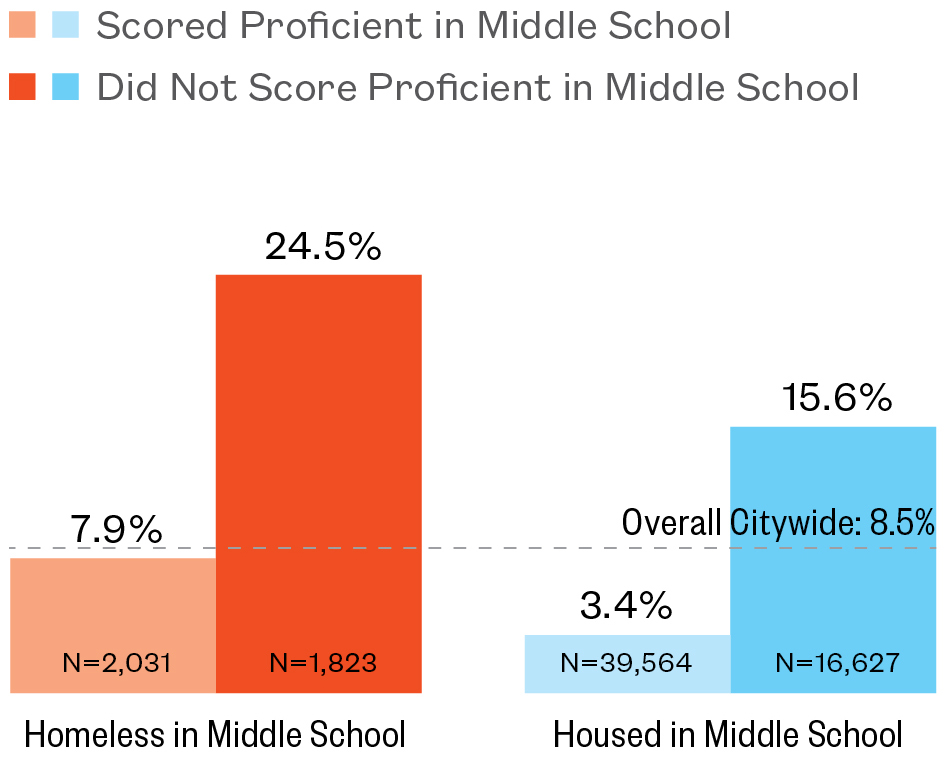

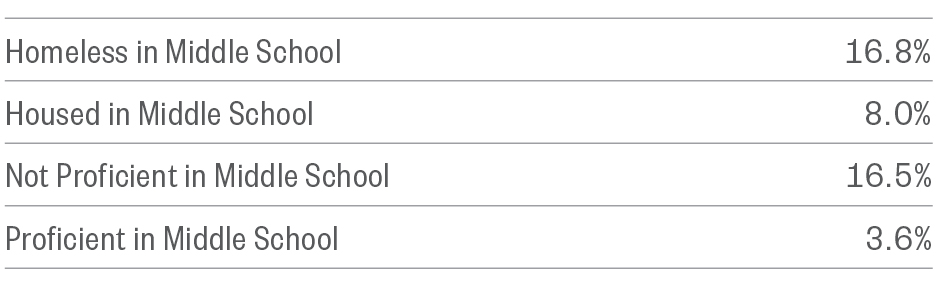

- Middle school proficiency is a strong predictor of dropping out of high school: overall, 16.5% of those who were not proficient ended up dropping out compared to 3.6% of students who did score proficient. For homeless students, this is an even stronger predictor. One in four (24.5%) homeless students who did not score proficient in middle school dropped out of high school.

How Are Homeless Students Faring?

SY 2015–16

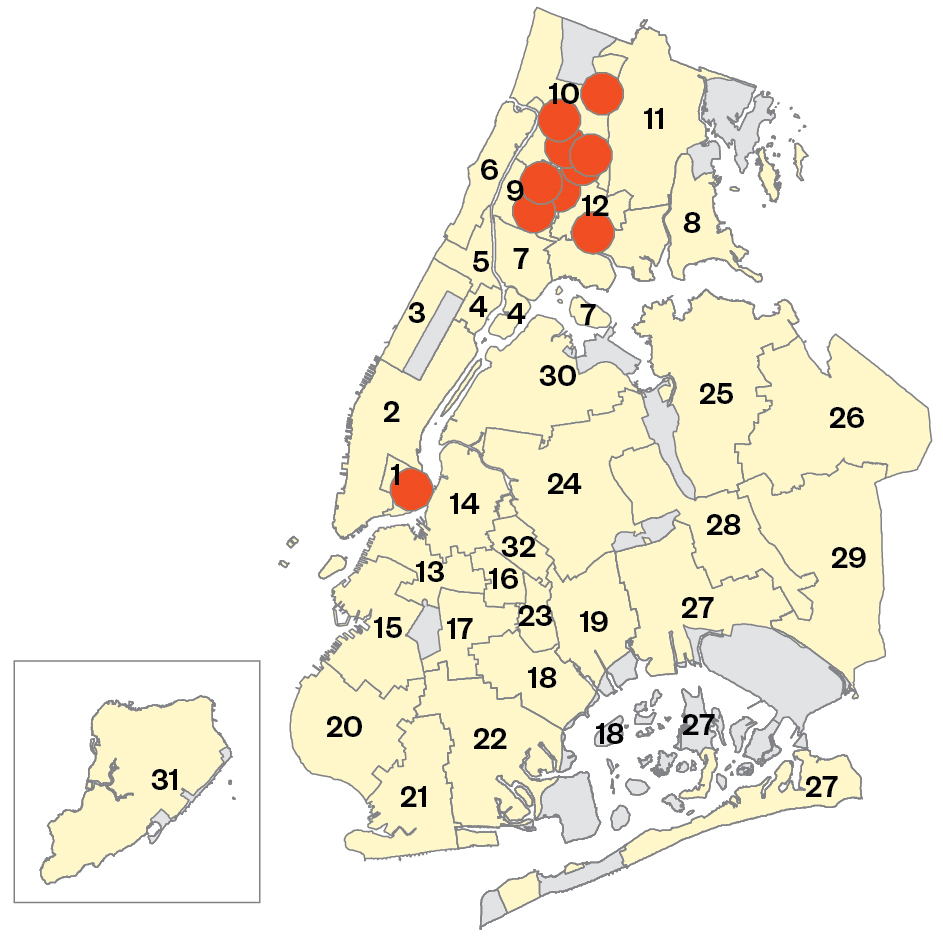

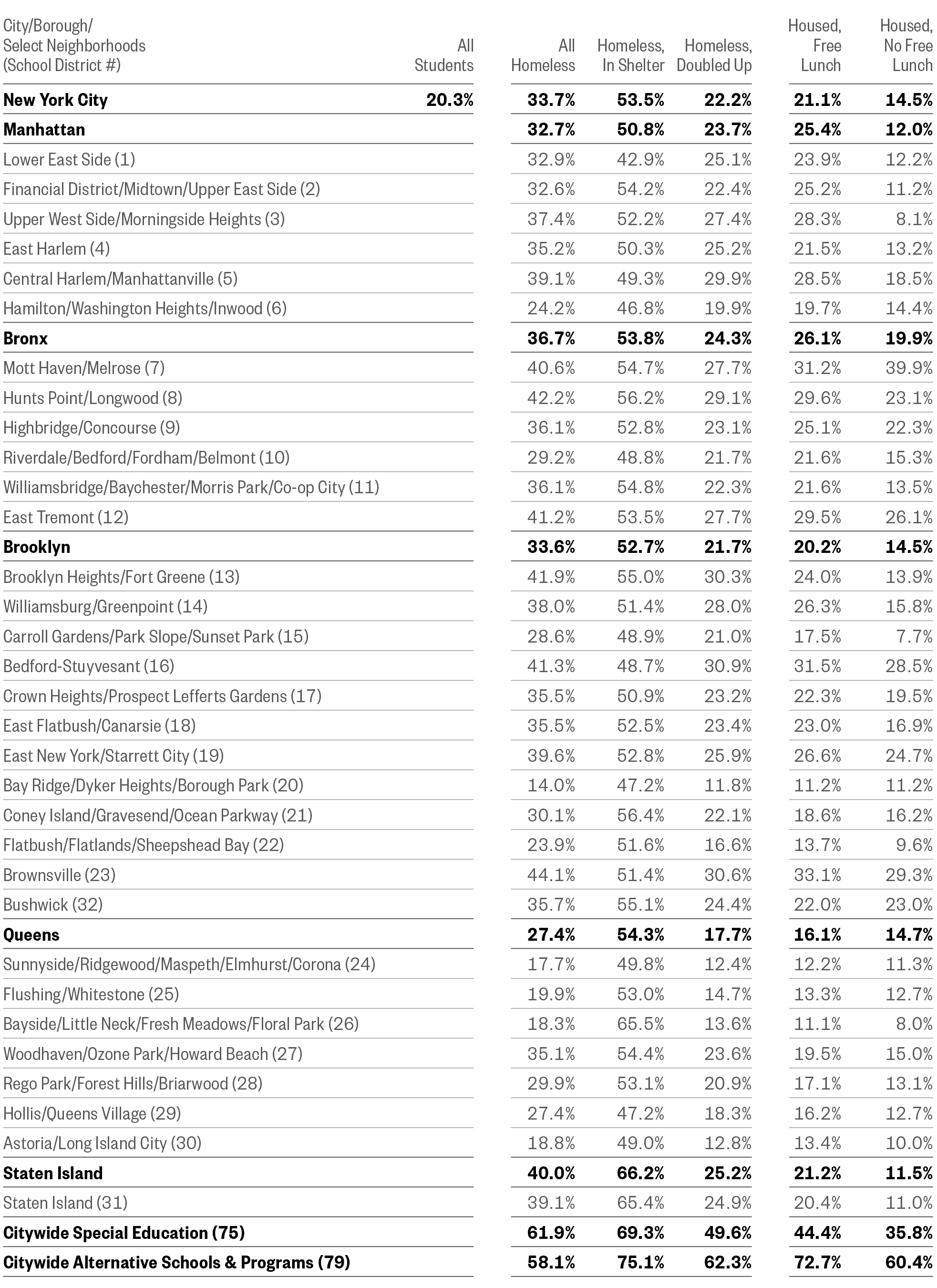

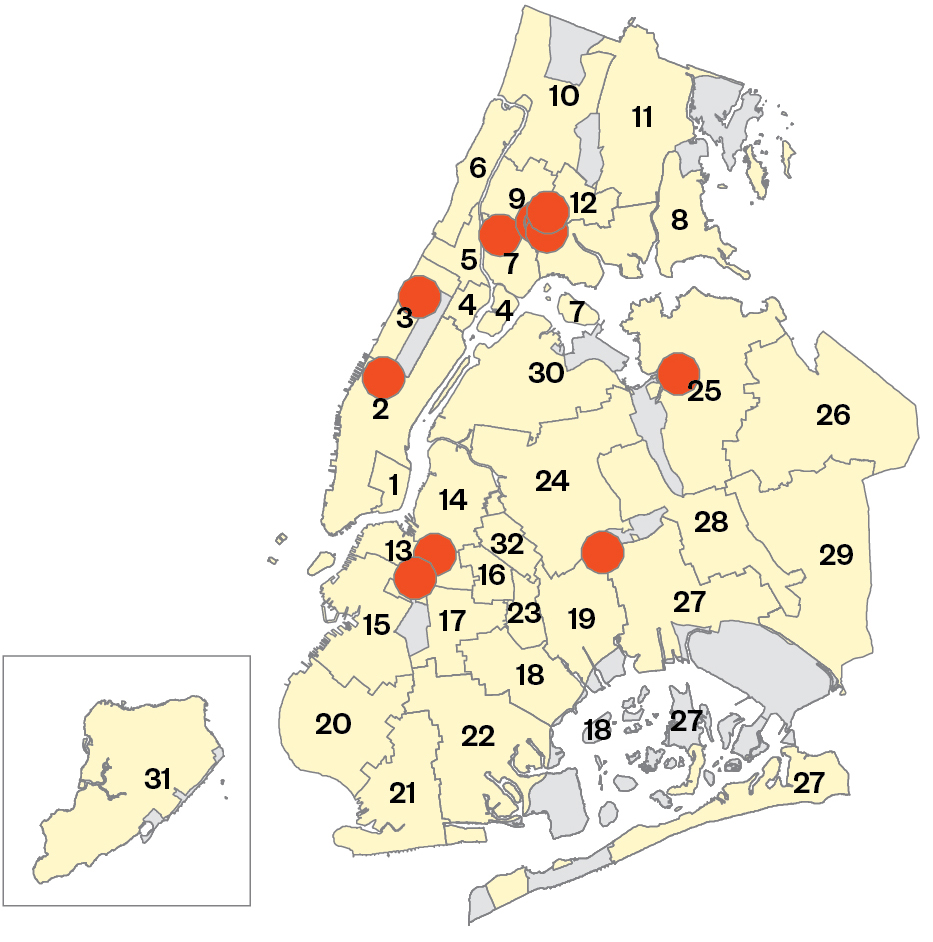

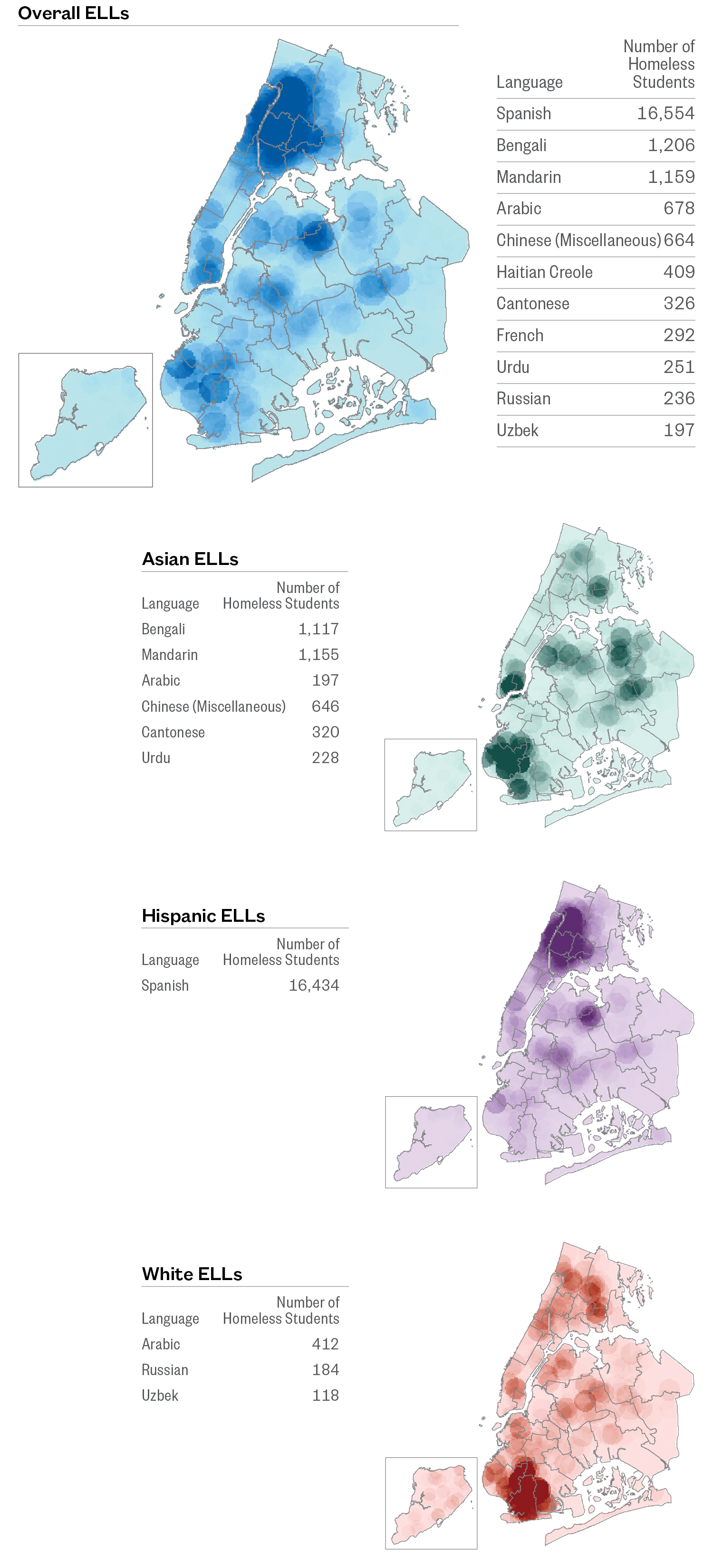

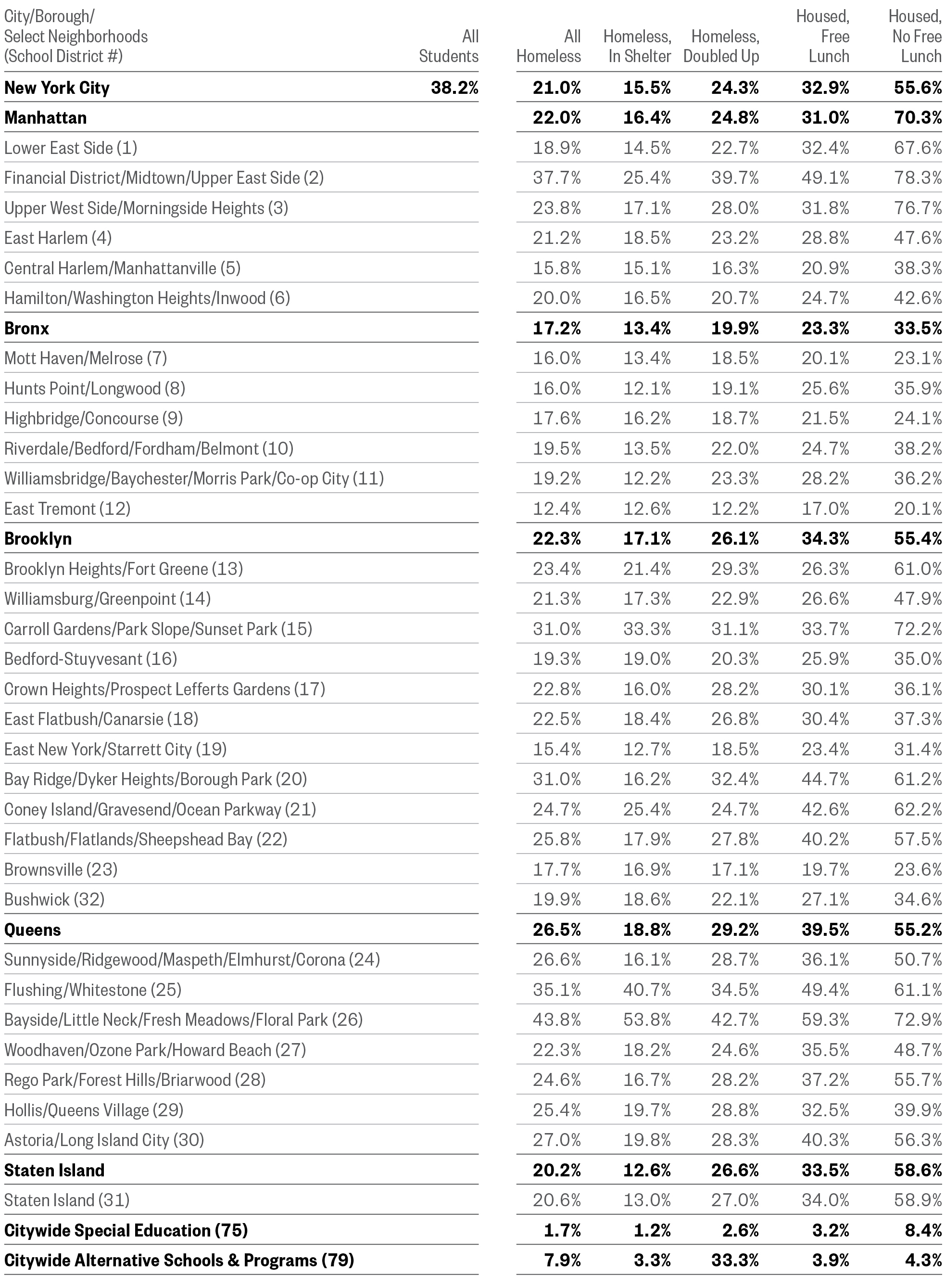

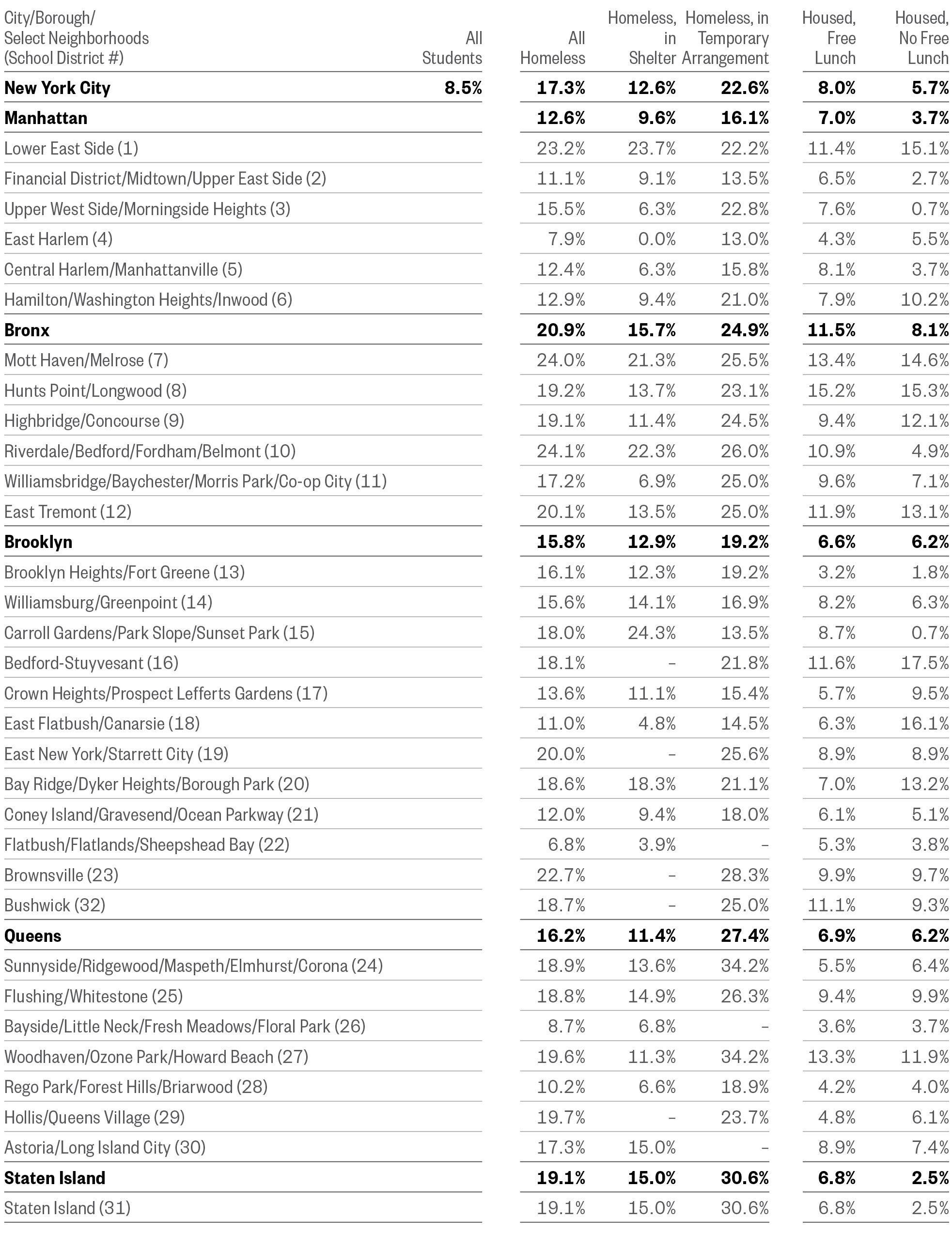

Key District-Level Findings

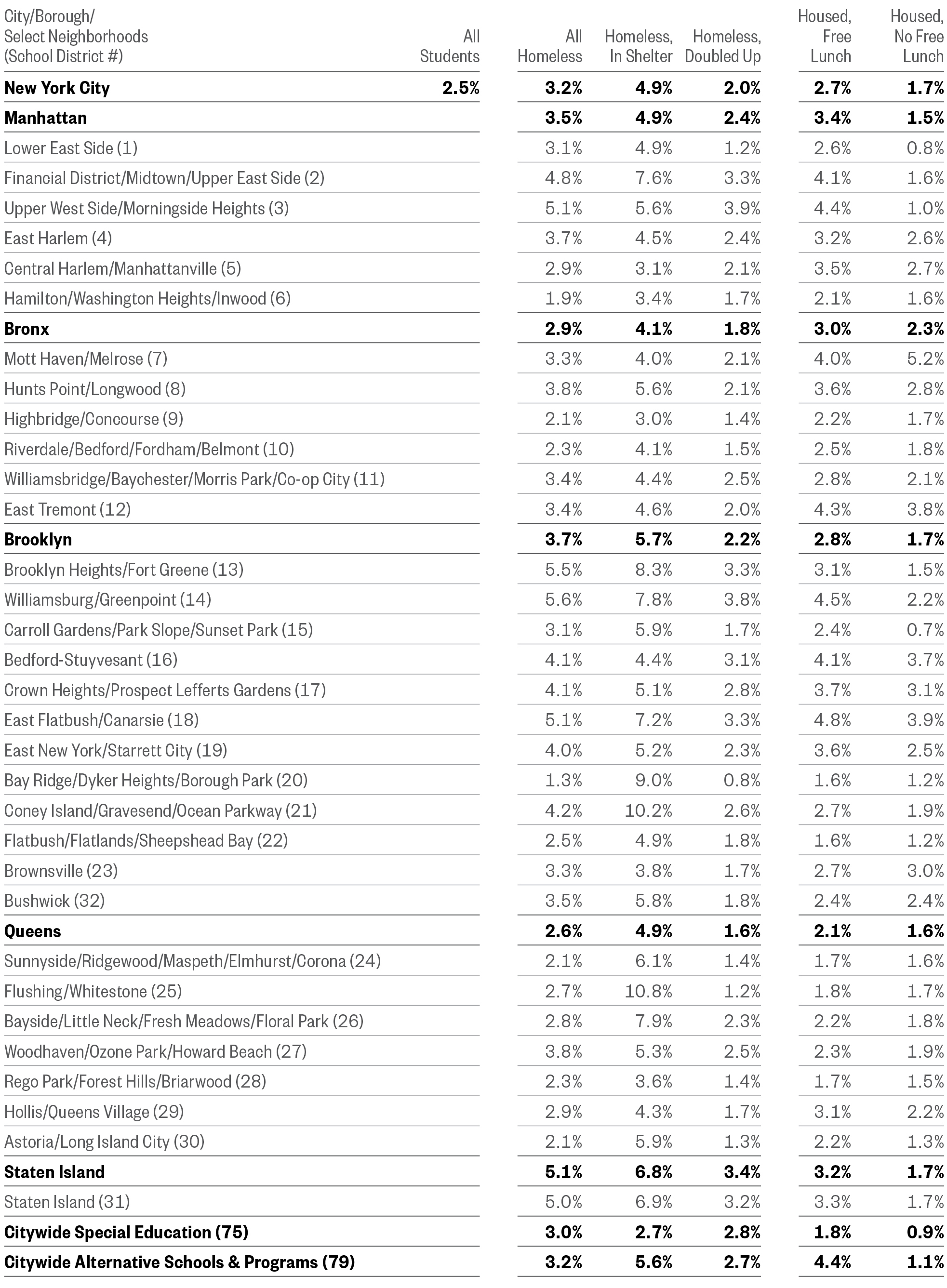

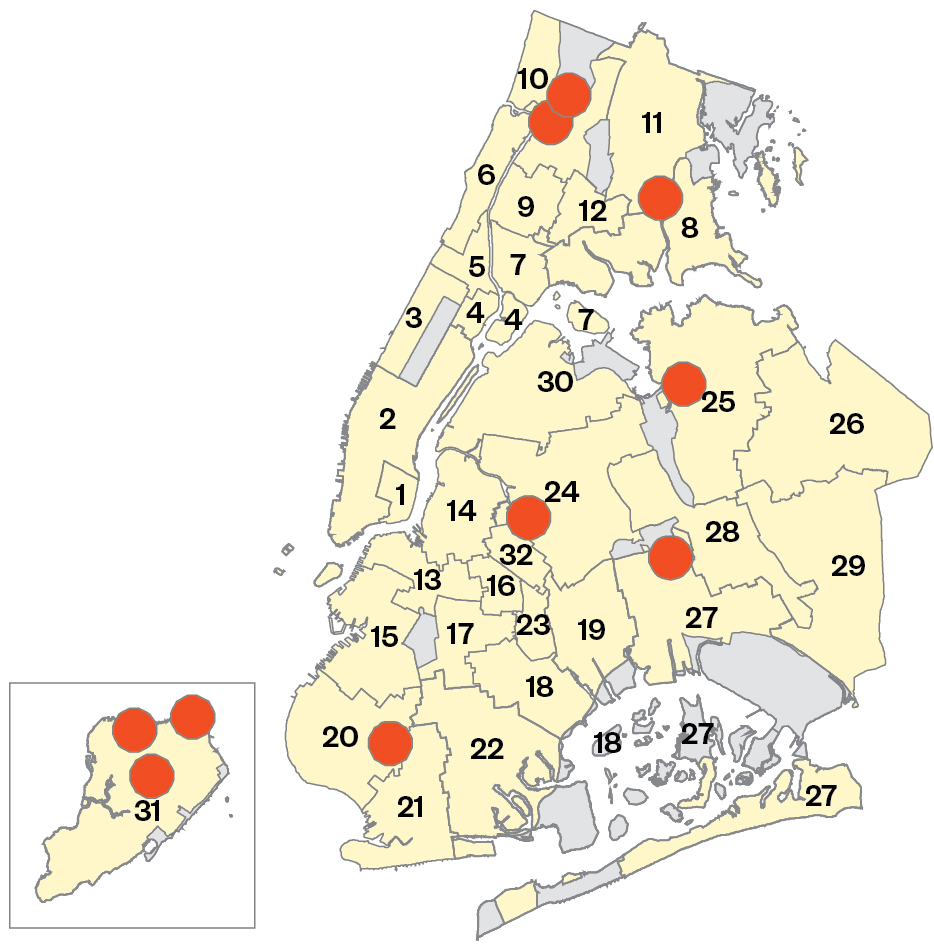

- The rate of student homelessness ranged from a low of 2.5% in Bayside, Queens to a high of 20% in the Bronx’s Highbridge/ Concourse. (Districts 26 and 9)

- Riverdale/Bedford in the Bronx continues to have the largest number of homeless students citywide (over 10,000). (District 10)

- Homelessness increased in every school district in New York City between SY 2014–15 and SY 2015–16.

- Both Flushing in Queens and Staten Island saw substantial growth in homelessness from the prior year, with increases of at least 520 homeless students each. This represented a 39% growth or more in the numbers of homeless students in those districts. (Districts 25 and 31)

- School districts located in areas of the Bronx, northern Manhattan, and central Brooklyn not only had large numbers of students who are currently experiencing homelessness, but also had an additional 6%–7% of students who were formerly homeless. (Districts 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 12, 16, and 23)

- By district, the share of homeless students with ELL needs ranged from just 5% of homeless students in Bedford-Stuyvesant to over half (52%) of homeless students in Bay Ridge. (Districts 16 and 20)

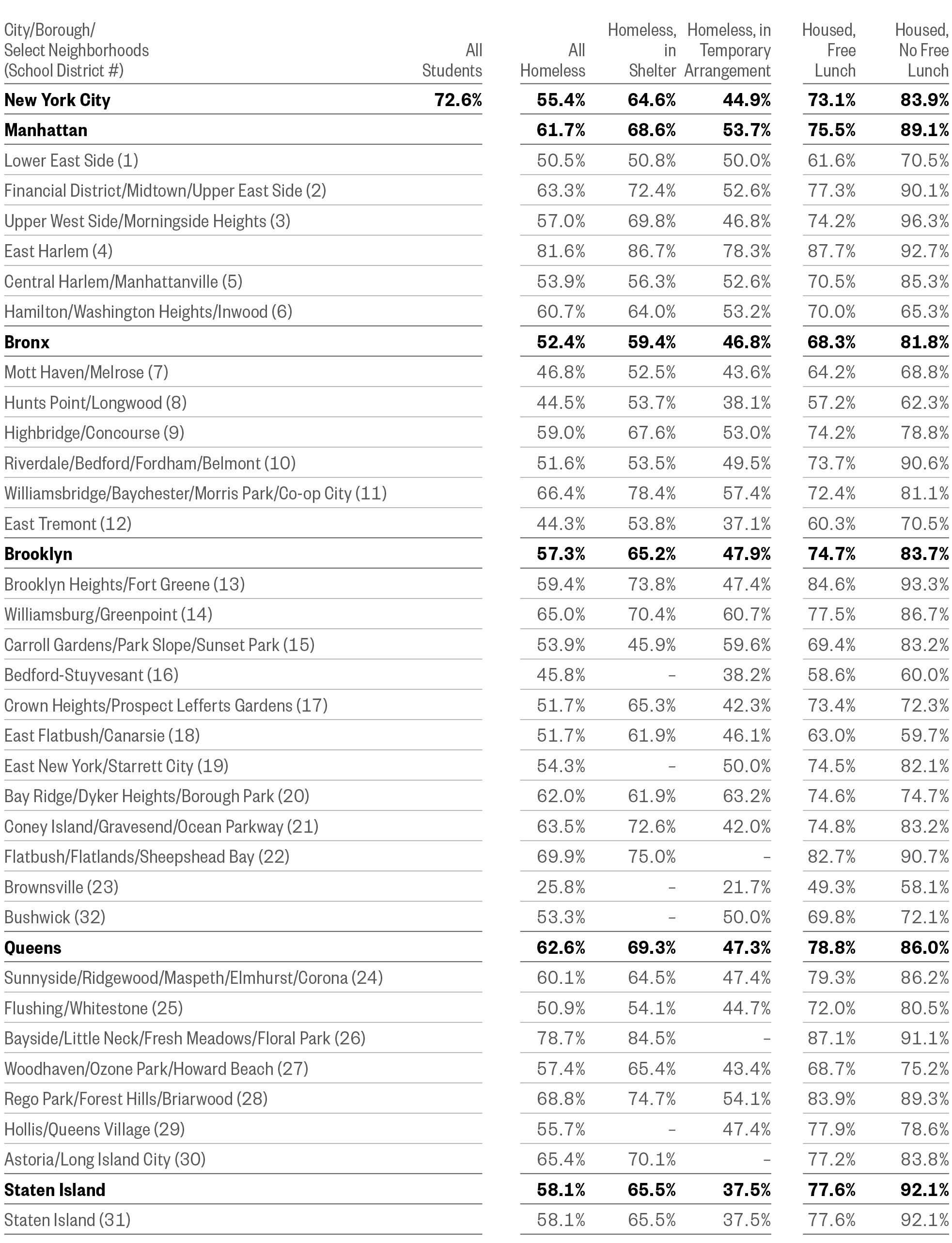

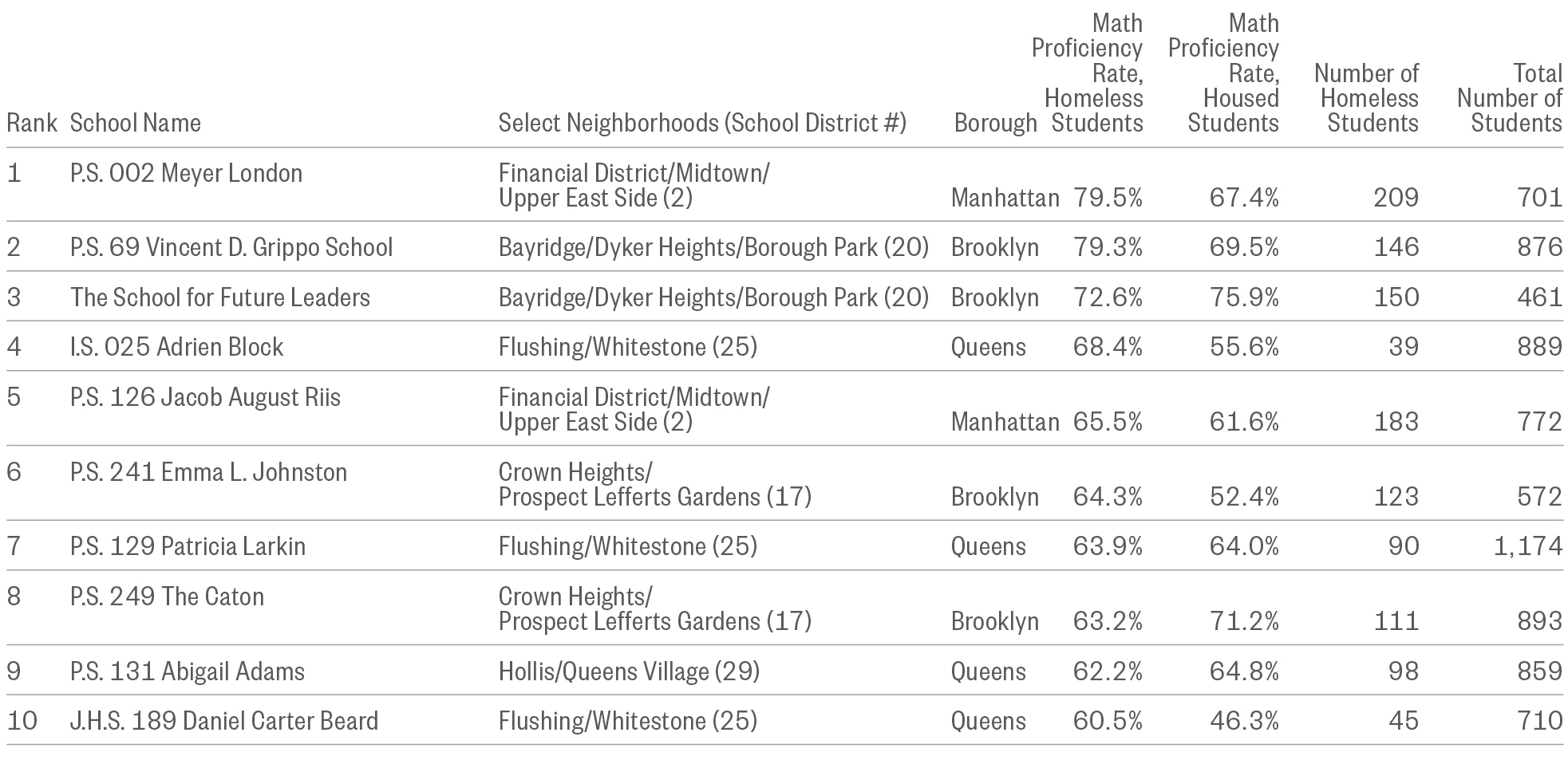

- Students in shelter were left behind academically compared to their classmates, in some districts scoring proficient at just one-half the rate or less of their housed and other homeless peers. This was true in the districts with the highest rates of math proficiency for homeless students, including the Financial District, Midtown, and Upper East Side in Manhattan, Bay Ridge/Dyker Heights in Brooklyn, and Bayside/Little Neck in Queens. (Districts 2, 20, and 26)

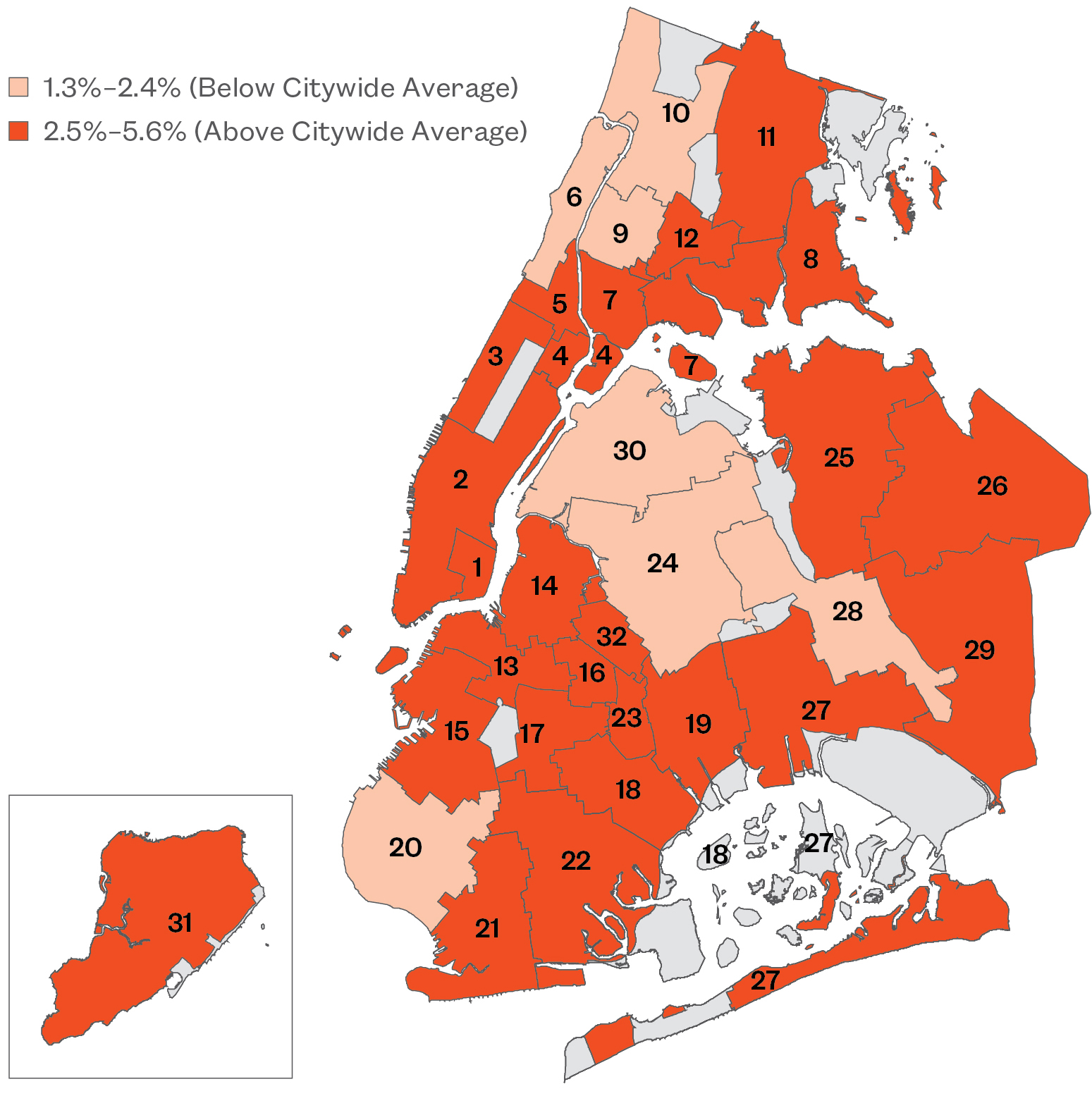

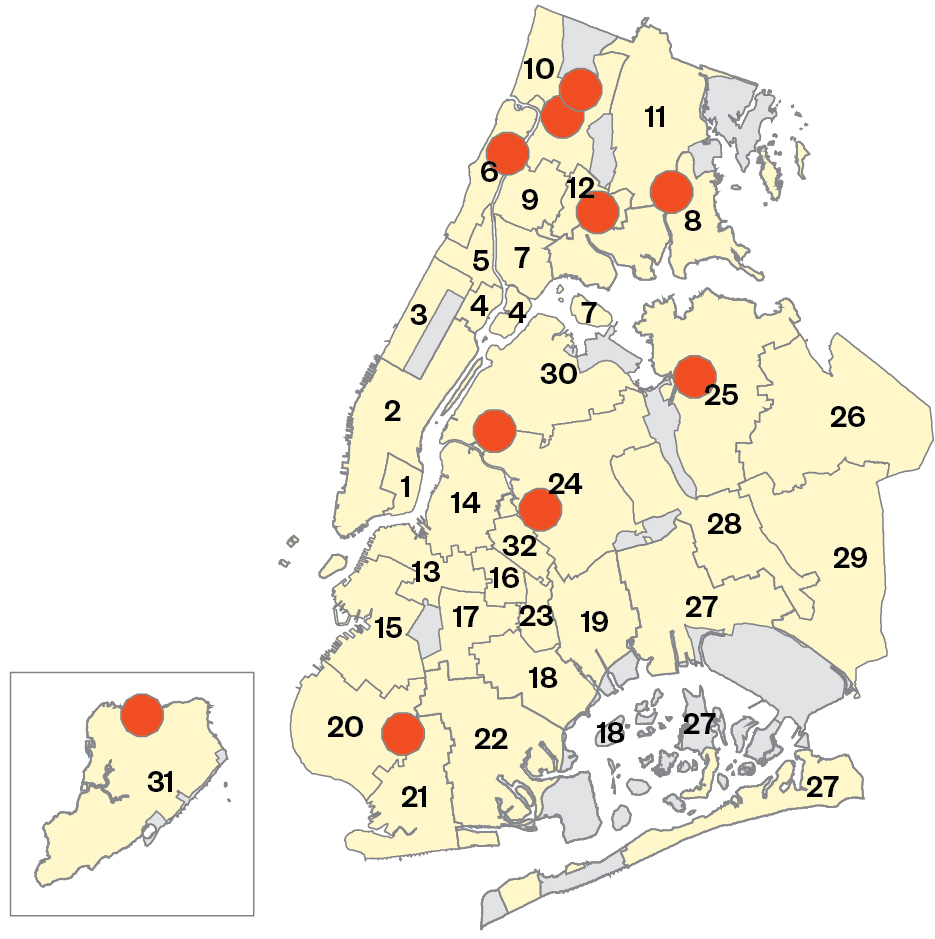

- In virtually every City school district, students in shelter were suspended at a higher rate than both their housed and doubled-up peers. The suspension rate for students living in shelter was the highest at 10.8% in Flushing, Queens— over four times the citywide average (2.5%). (District 25)

- Homeless students attending school in Manhattan’s East Harlem and Bayside in Queens had the highest graduation rates for homeless students citywide, and even exceeded the overall graduation rate for the class of 2016 (82% in District 4 and 79% in District 26; 73% overall). Meanwhile, in four districts located in the Bronx and Brooklyn, less than 46% of homeless students graduated, a rate nearly 30 points lower than the citywide average (73%). (Districts 8, 12, 16, and 23)

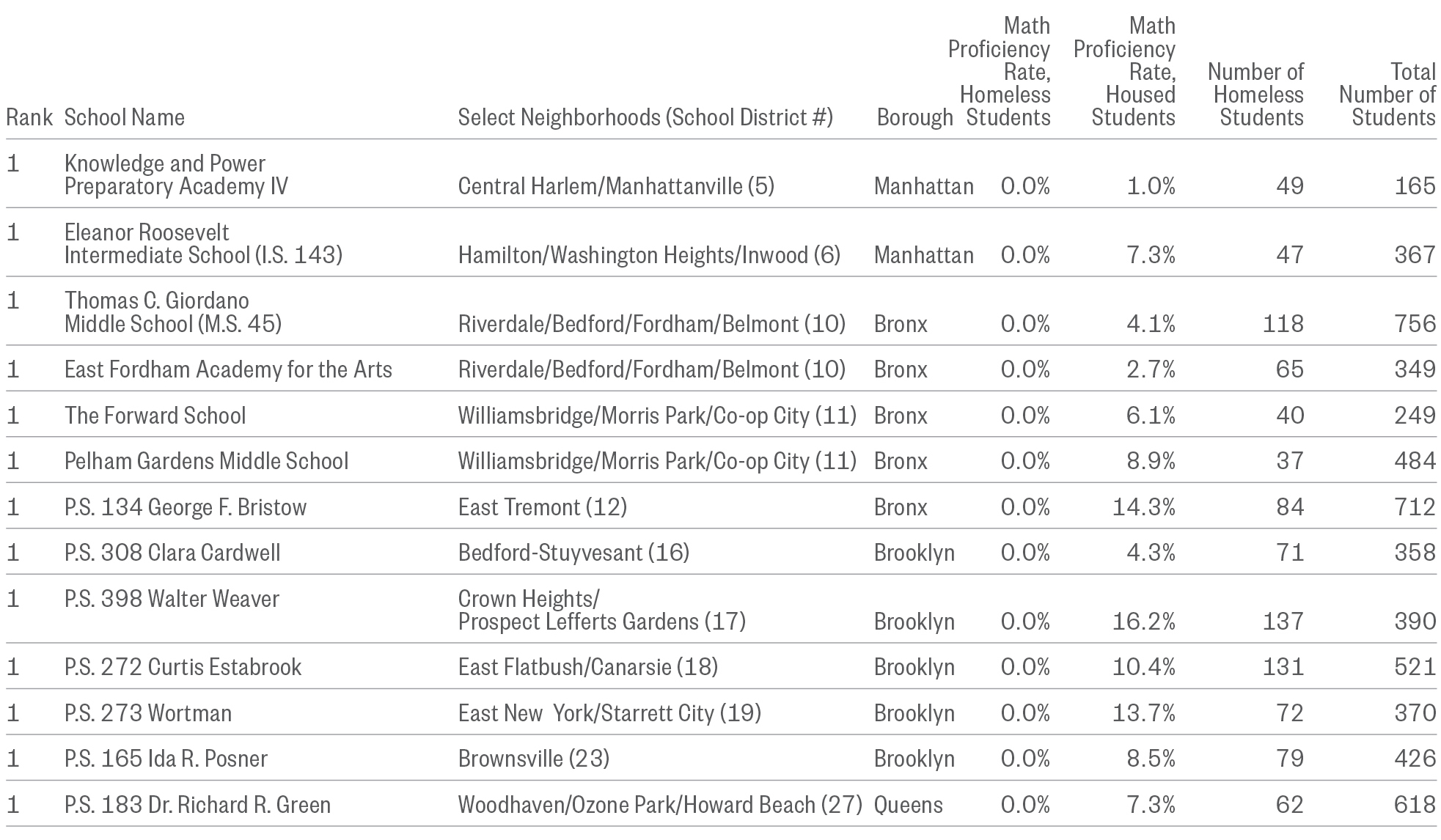

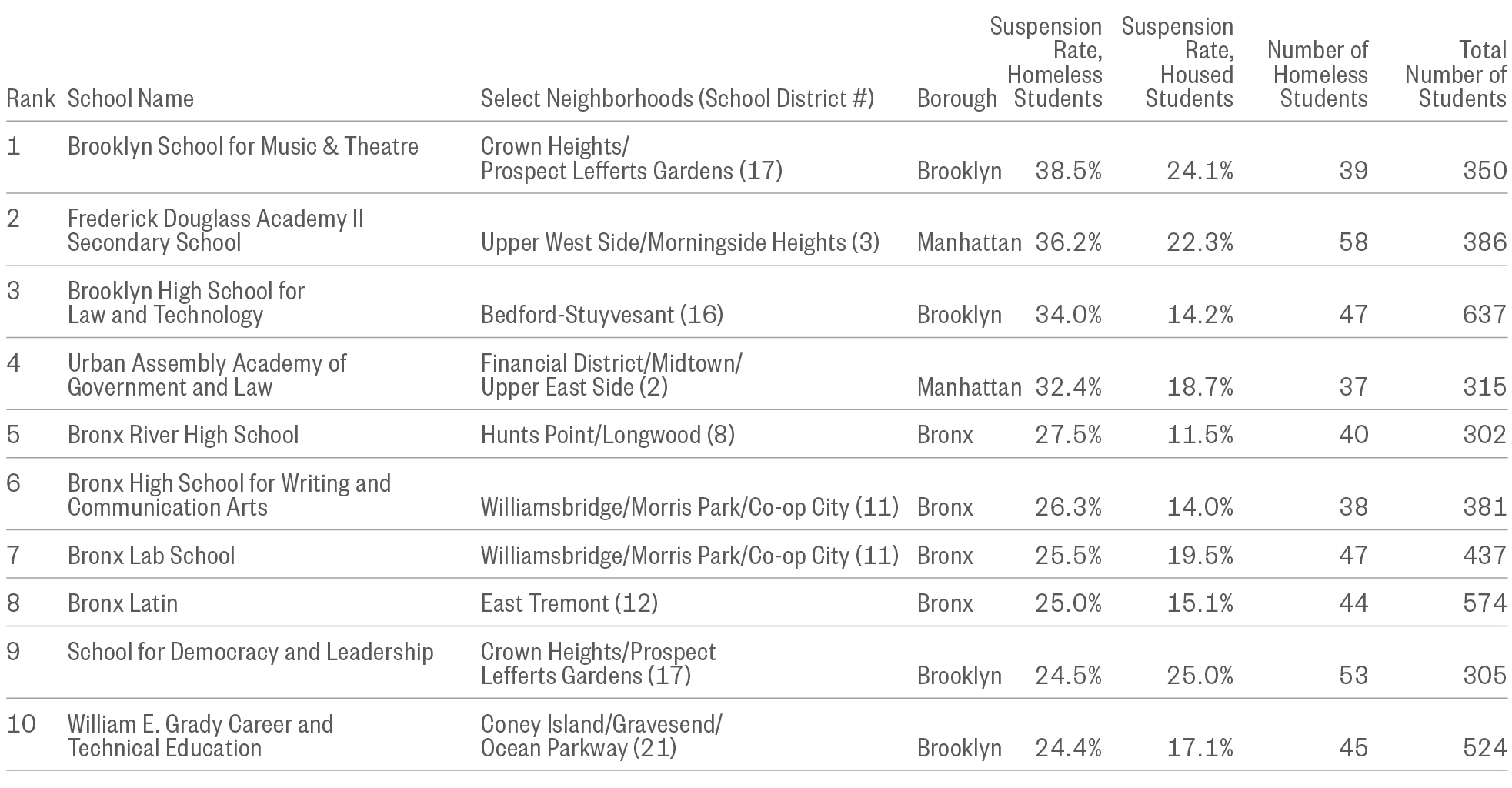

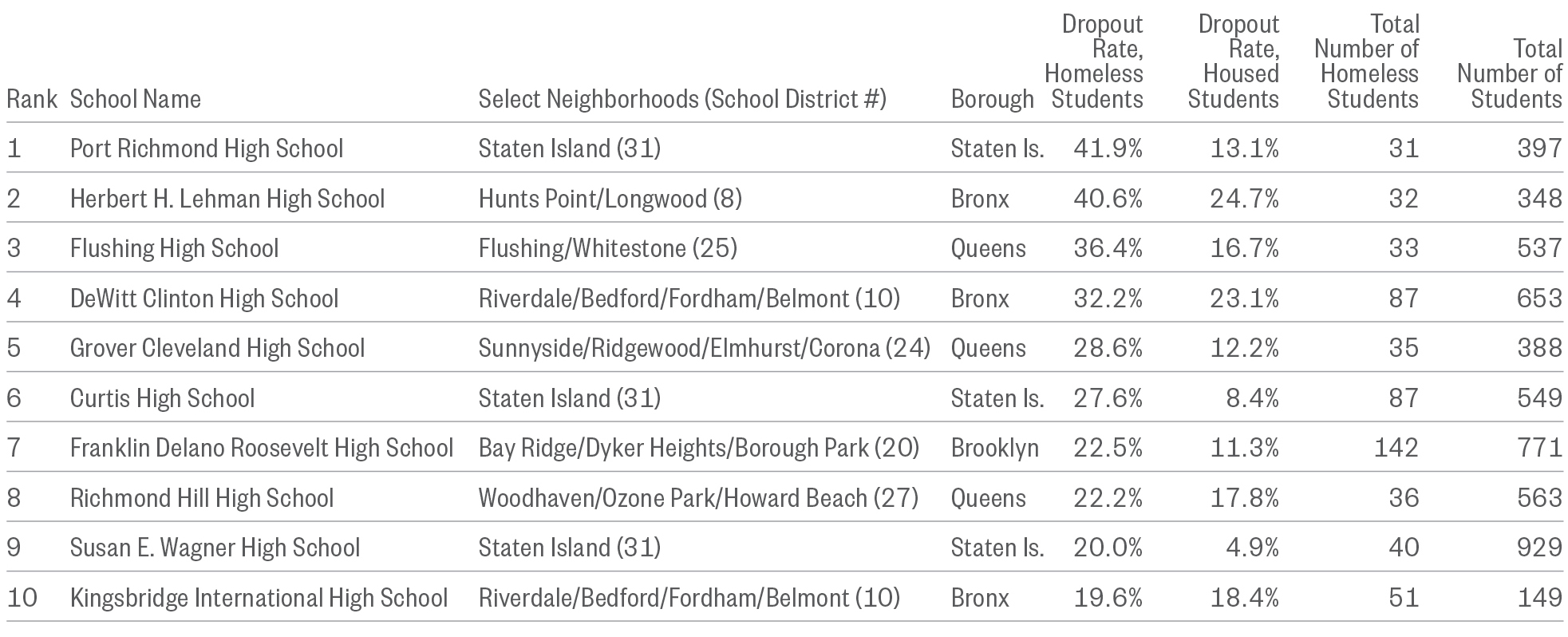

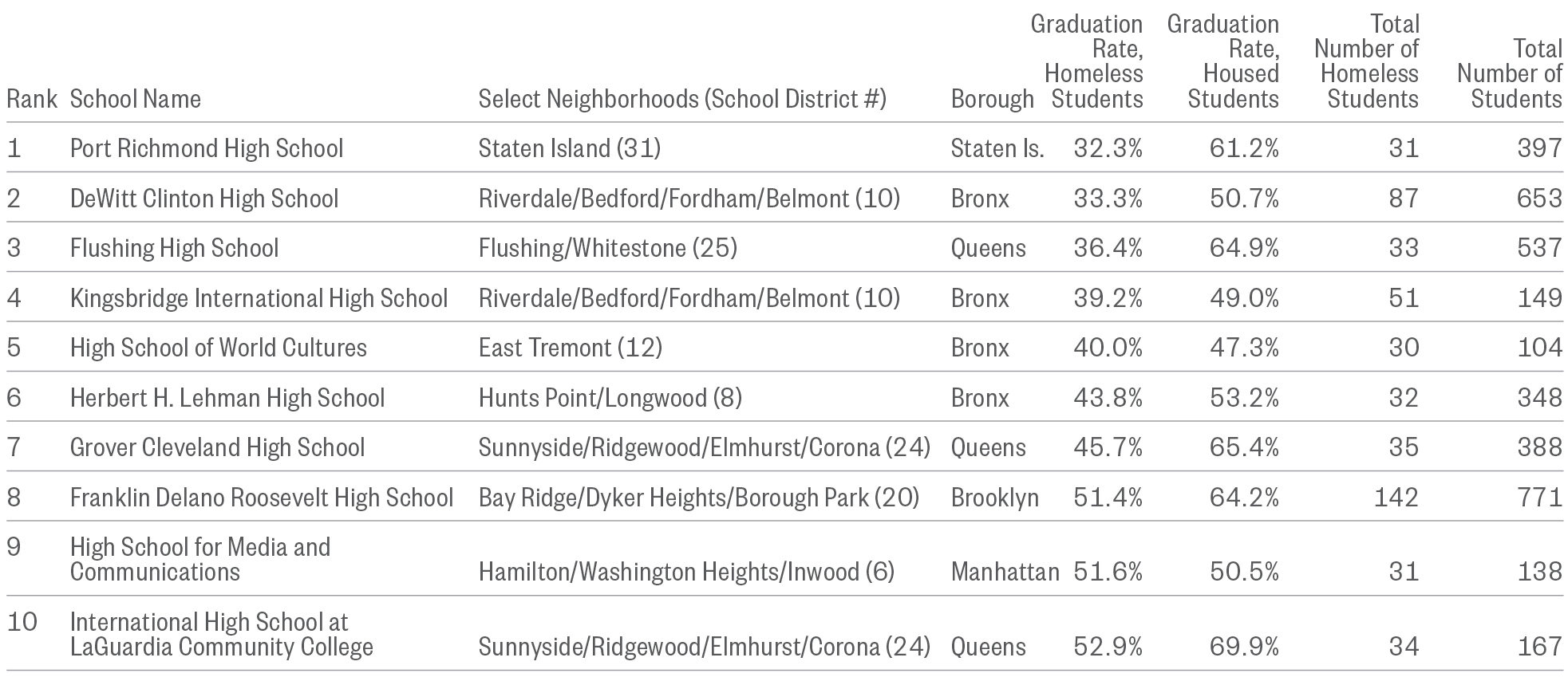

Key School-Level Findings

- Two schools located in Norwood and Highbridge/Concourse had the most homeless students transferring into the school mid-year (126 and 125 students each). In these schools, homeless students represented more than half of all students who transferred in mid-year, while citywide, homeless students represented 24% of students who transferred mid-year. (Districts 10 and 9)

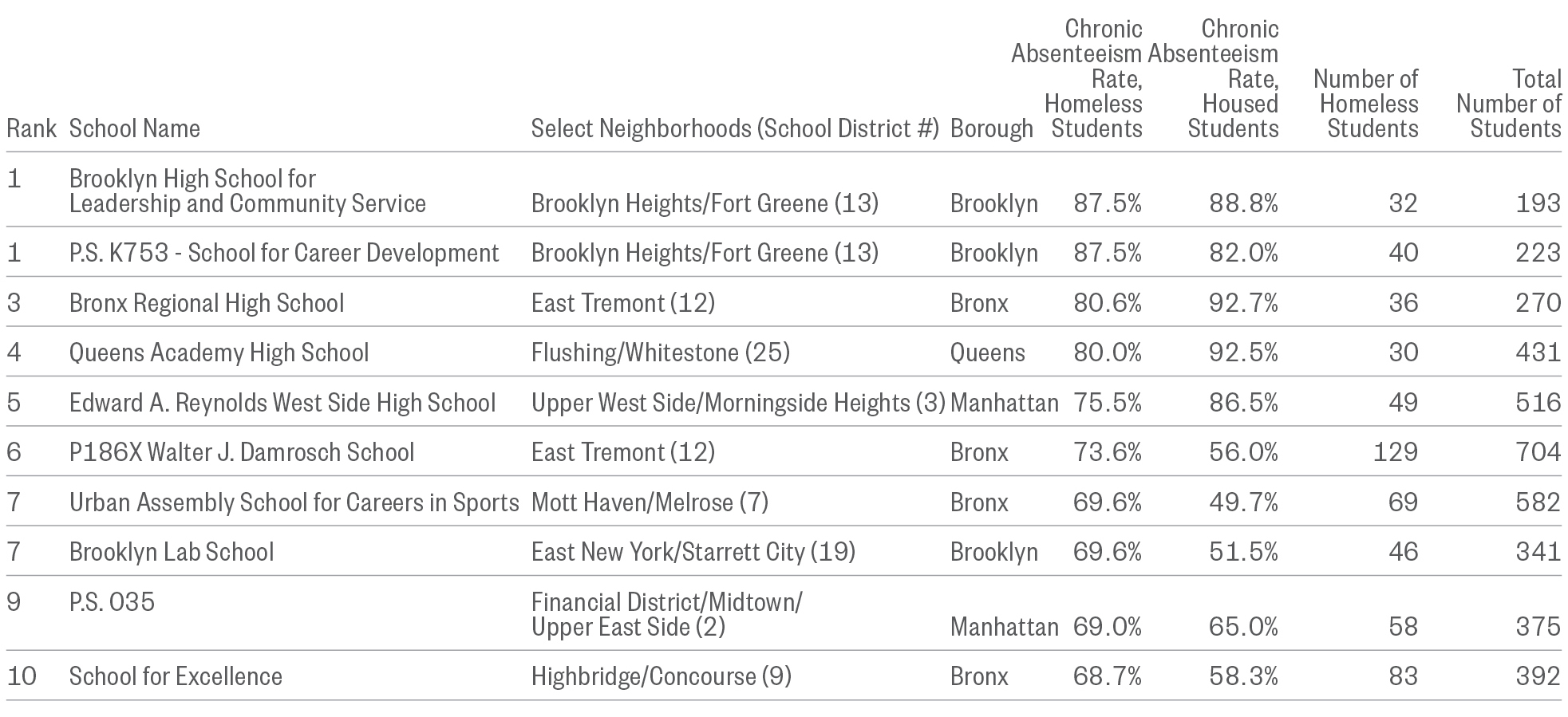

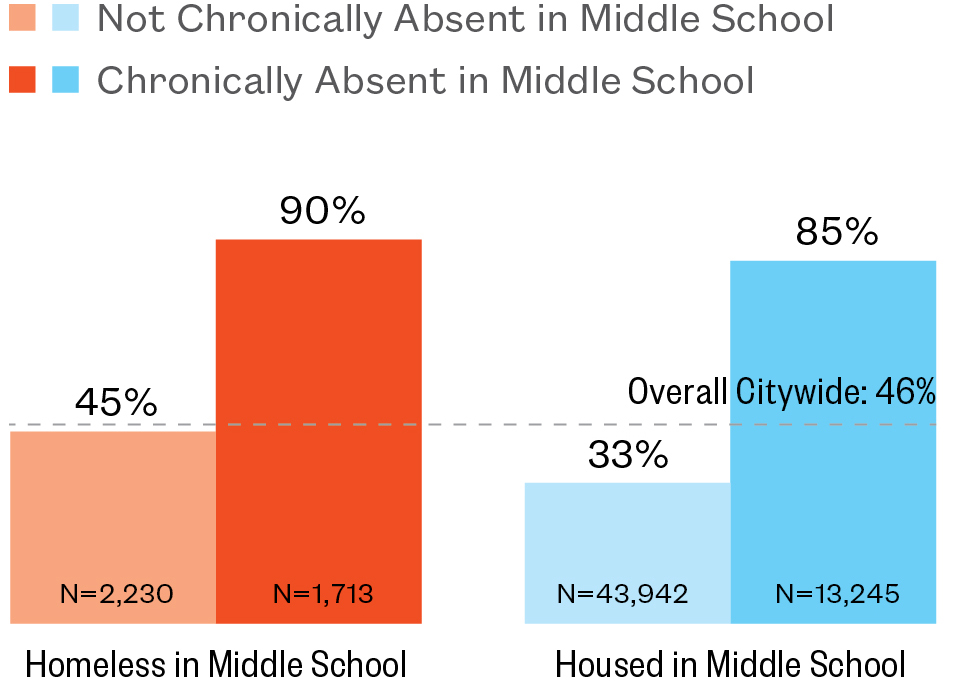

- Schools with the highest rates of absenteeism for homeless students were likely to be schools where housed students struggled as well. Close to 90% of homeless students were chronically absent at two high schools in Clinton Hill, while over 80% of their housed classmates were chronically absent. (District 13)

- ELA proficiency rates for homeless students ranged from 0% in two schools citywide to a high of 66% in one school located in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. (District 17) Citywide, 21% of homeless students scored proficient in ELA.

- At the school level, proficiency rates were similar between housed and homeless students: among schools in the top for highest math proficiency rate of homeless students, the proficiency rate for housed students exceeded the overall citywide average. Similarly, in most of the 13 schools where no homeless students scored proficient, the housed student rate was 10% or less.

- Charter schools with the highest rates of student homelessness (9%–18.5%) were clustered in the districts where the most homeless students attend public schools. By contrast, in public schools in those districts, up to 48% of students were homeless.

- School suspensions disproportionately affect homeless students, but also some schools overall. At the ten schools with the highest suspension rates for homeless students, an average of 29% of homeless students and 18% of housed students were suspended, compared to a citywide average of 2.5%.

Download the Executive Summary.

To explore homelessness in New York City schools, try our interactive map.

To learn more about the educational outcomes of homeless New York city students, try our Student Atlas app.

Return to top.

Section 1

Growth of Student Homelessness in New York City

“Every six months, it’s like you’re in a new family. It’s so destabilizing. One of the biggest problems is that the next housing assignment is not in the same community. If the housing assignment is anywhere near where they were, you could stabilize those kids in schools. But if you’re going from Rockaway to Staten Island to the Bronx, any kid would really lose it. We would lose it if our home moved every six months and the people we know and trust weren’t available to us. … It takes several months to gain the trust of a student and to figure out what kind of learning support they need, to put a program in place. By January you’re feeling the flow and have figured out what triggers a tantrum or causes the child to run away. Just as you start to figure it all out, the kids are gone.”

—Former Principal, Community School in Brooklyn

“We work with a fourth-grade student who was placed in a shelter in Manhattan and he misses a lot of school. If the bus is late, or if he misses the bus, or if he sleeps in for five minutes, there’s no way for him to get to school. He’s very delayed. He’s made a lot of progress this year, but he feels like he doesn’t have many friends. He doesn’t know a lot of the kids because they live close to the school in the neighborhood, and they have been going to the same school since pre-K.”

—Social Work Director, Partnership with Children, working in Brooklyn public schools

More than 140,000 New York City public school students have been homeless at some point between SY 2010–11 and SY 2015–16. One in seven New York City children will be homeless before they finish elementary school unless current trends change. Looking at this cohort over six years, children who were homeless in elementary school faced heightened school instability and educational challenges. This section explores where students experiencing homelessness are attending school, building off of the 2016 Atlas of Student Homelessness to examine the patterns of formerly homeless students in public schools and homeless students attending charter schools in SY 2015–16.

What’s New?

- The number of homeless students in NYC public schools jumped by 20% in just one year, reaching close to 100,000 students in SY 2015–16.

- In addition to the nine percent of students homeless in SY 2015–16, another four percent were currently housed but had experienced homelessness at some point since SY 2010–11 (formerly homeless).

- On average, 6.6% of students in New York City charter schools were homeless in SY 2015–16—lower than the rate among students in public schools (9.3%).

Policy Considerations

- Every type of unstable housing setting is not the same. Living in a shelter, living doubled up, or having a history of housing instability can impact children’s lives differently. Identifying students by their specific experience is one critical tool that can help educators and policymakers further target interventions to children who are most vulnerable.

- Children are most likely to experience housing instability and homelessness when they are young. Identifying barriers and supporting young homeless students and their families is crucial to helping them access early education programs.

Student Homelessness Is Growing

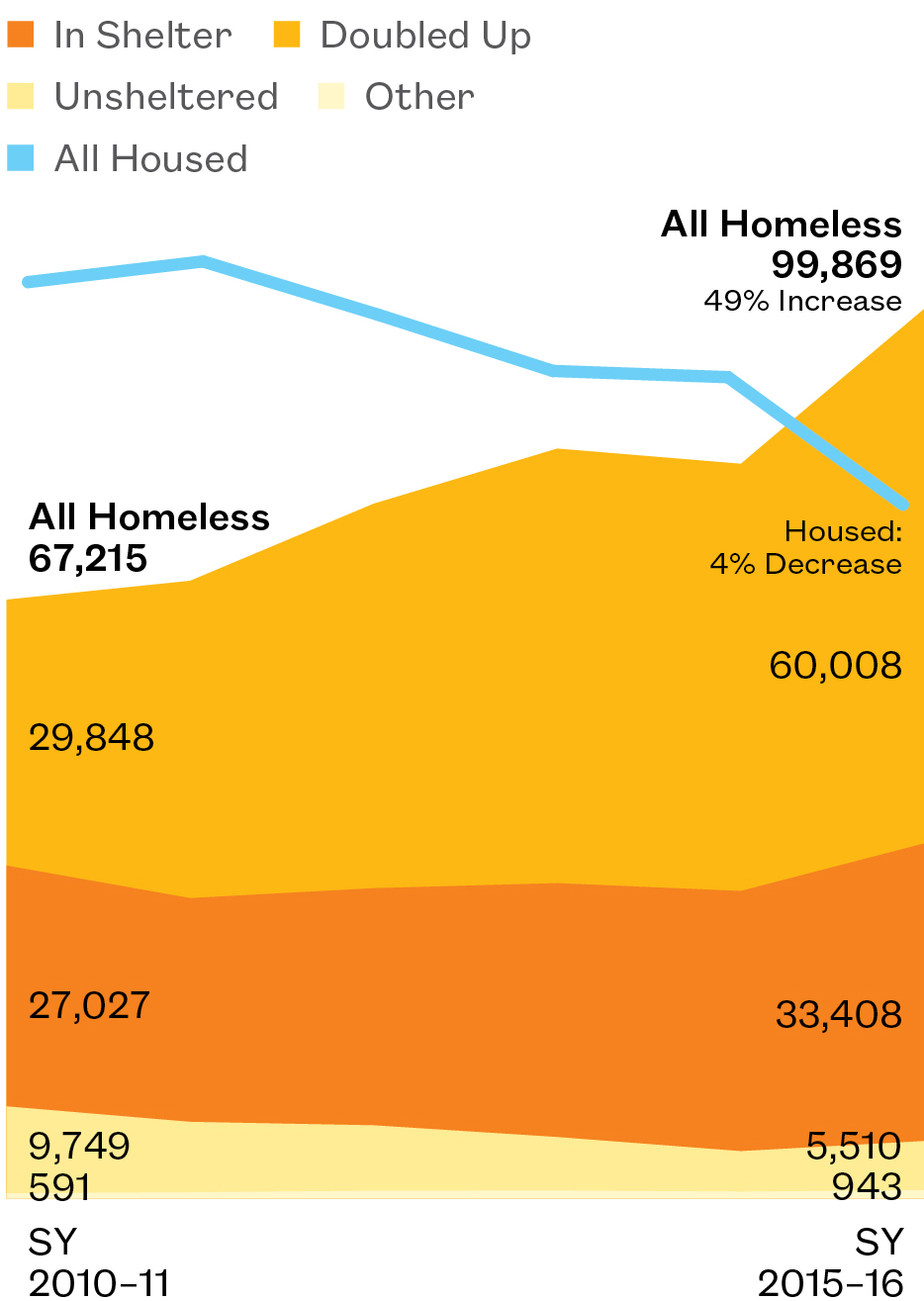

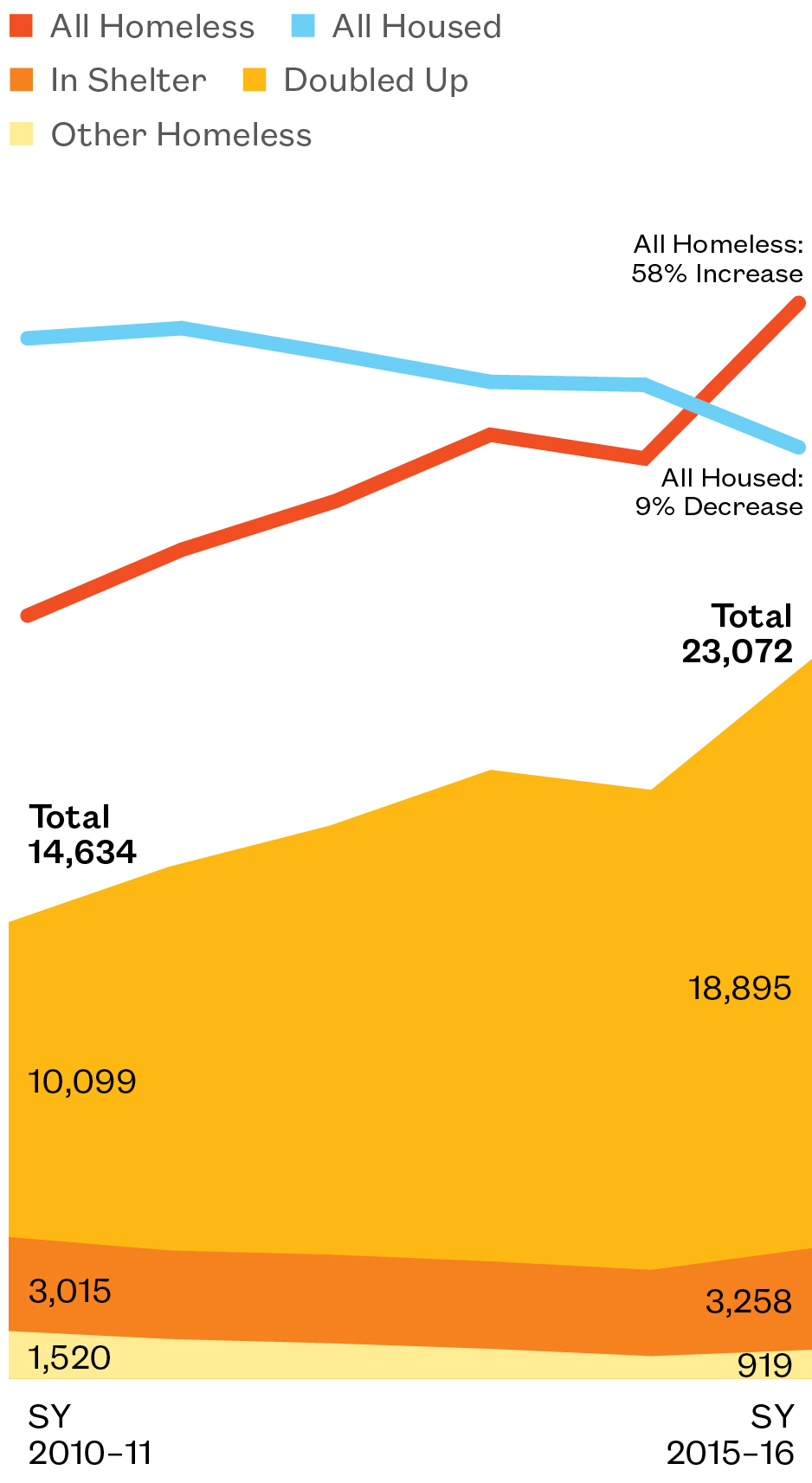

- Close to 100,000 homeless students attended New York City public schools in SY 2015–16. This was a 49% increase in six years. Over the same period, the overall enrollment among housed students declined.

- This increase was seen across housing statuses, with doubled-up students driving the growth. The number of doubled-up students grew to over 60,000 in SY 2015–16, a 25% increase from the prior year.

- For every homeless student living in shelter, roughly two more are homeless living in some other temporary location, such as doubled up with another family.

With little growth in City family shelter capacity, more and more families are doubling up. Ensuring that the varied social and educational needs of the close to 100,000 homeless students are met will be critical for New York City’s future.

Homeless Students in New York City Public Schools

SY 2010–11 to SY 2015–16

Note: In earlier years, the total number of “unsheltered” students may be less reliable than other categories.

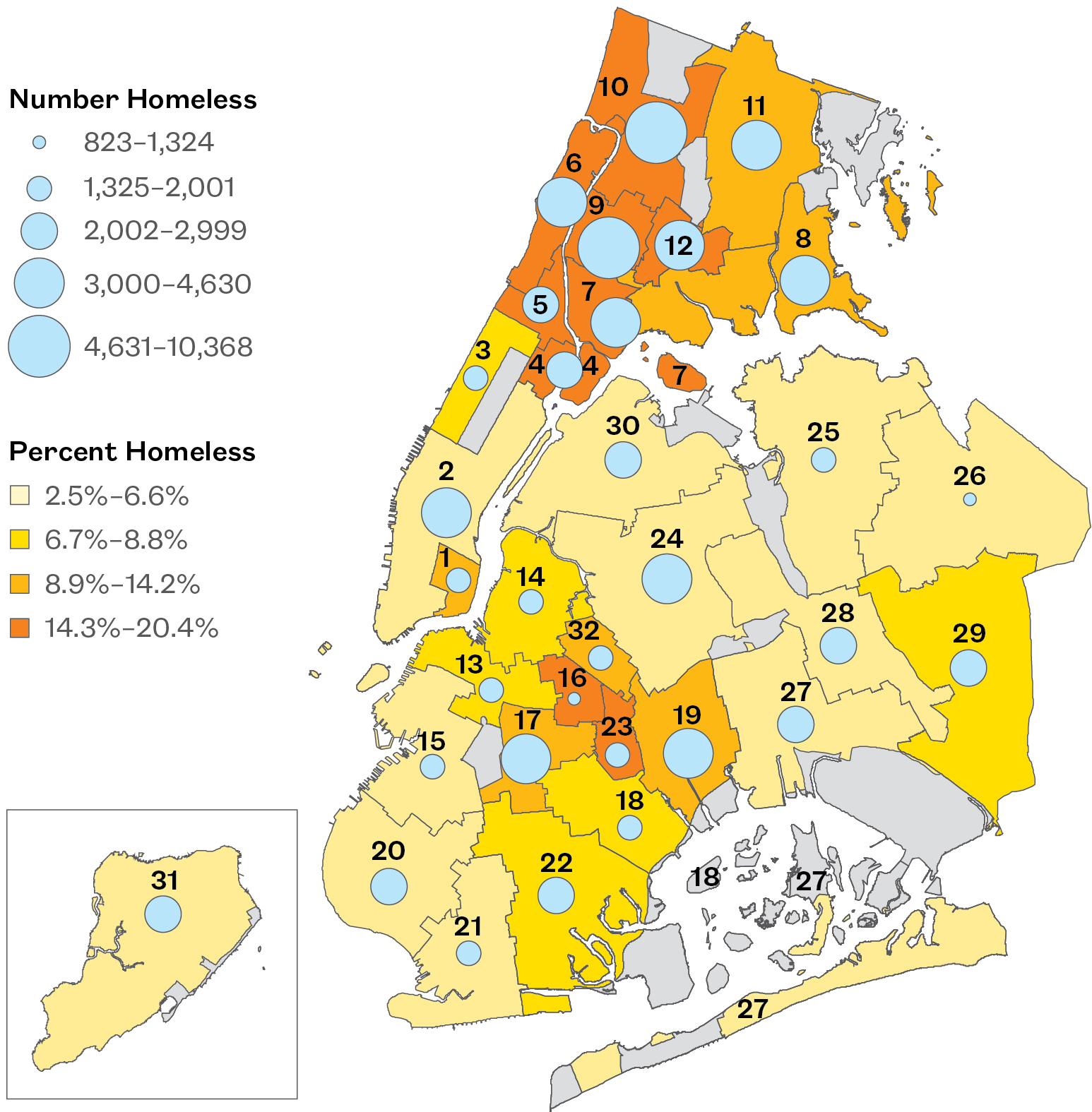

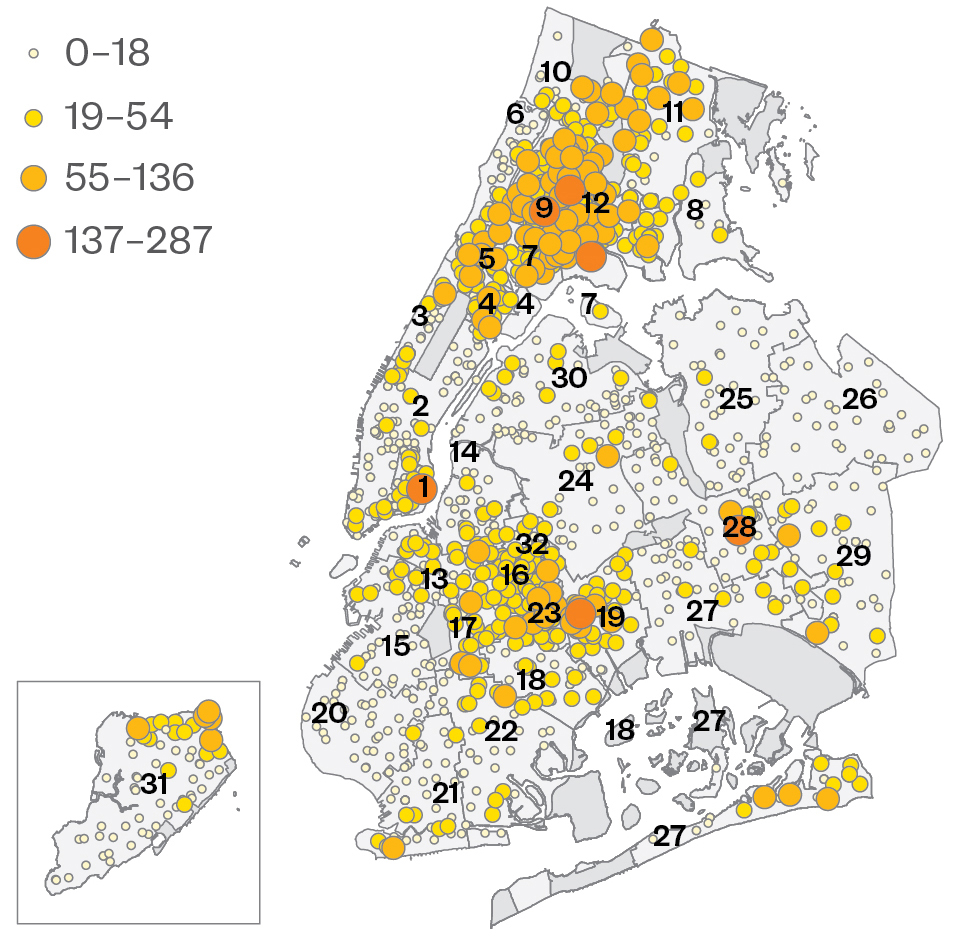

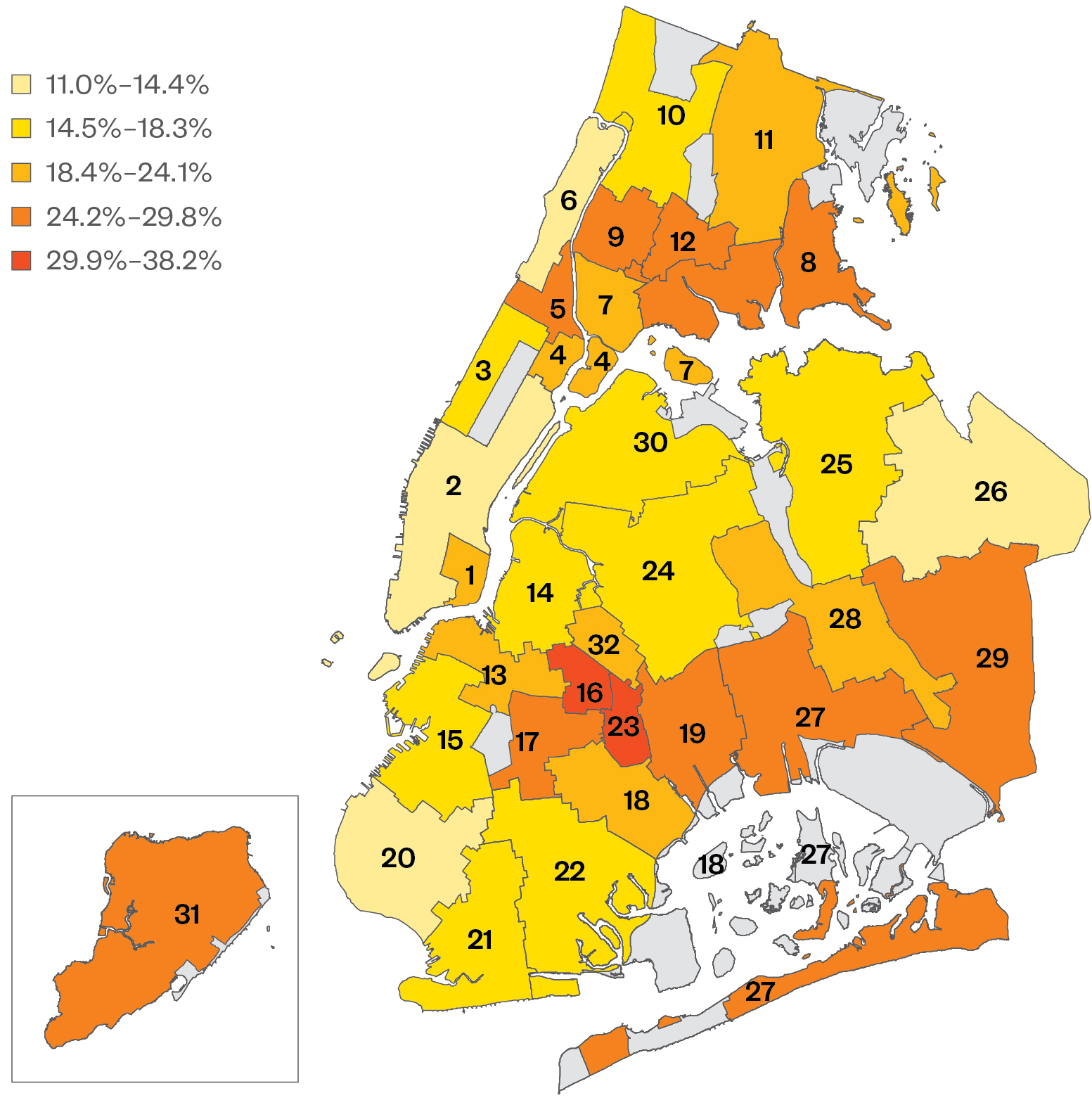

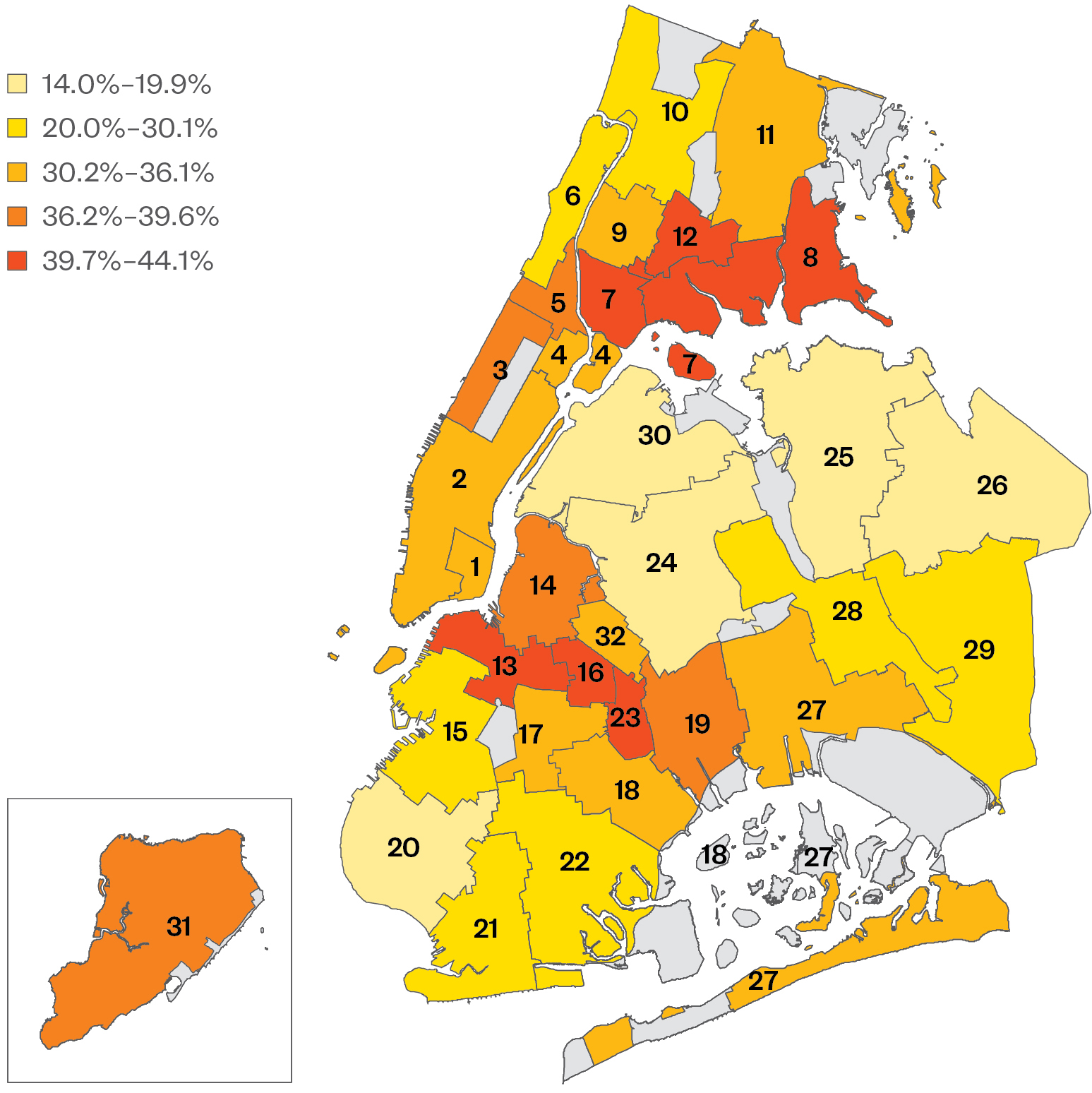

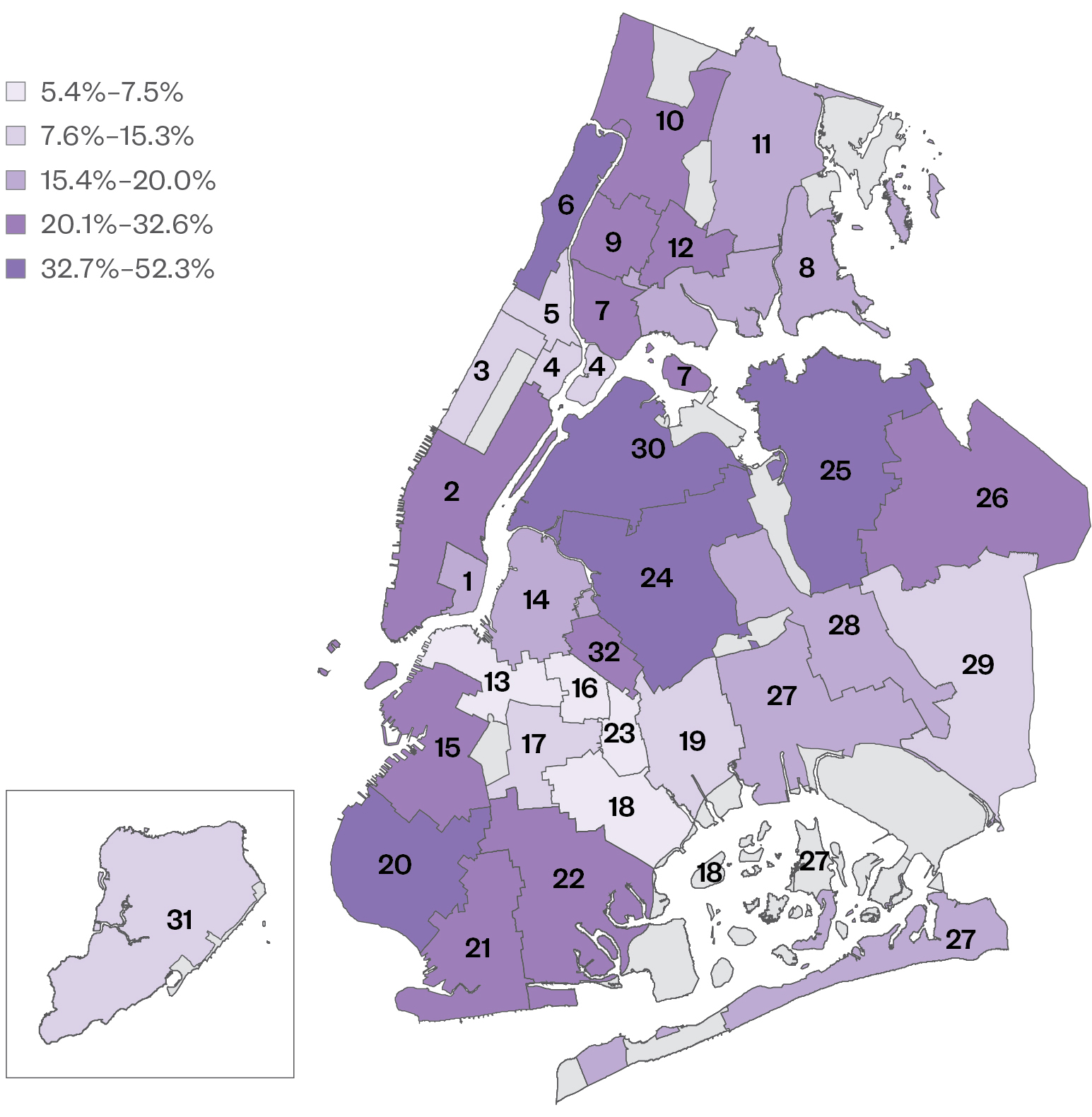

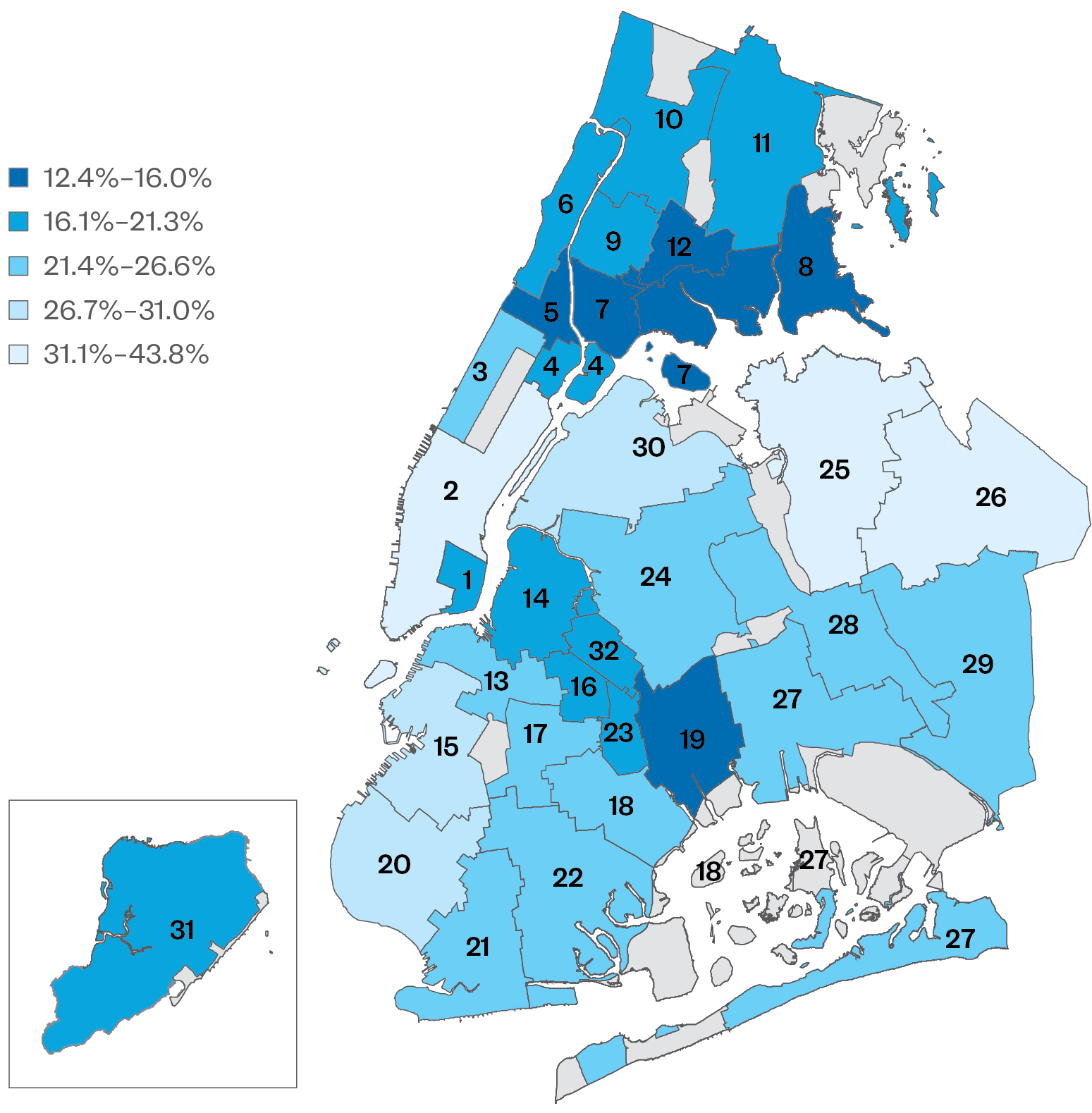

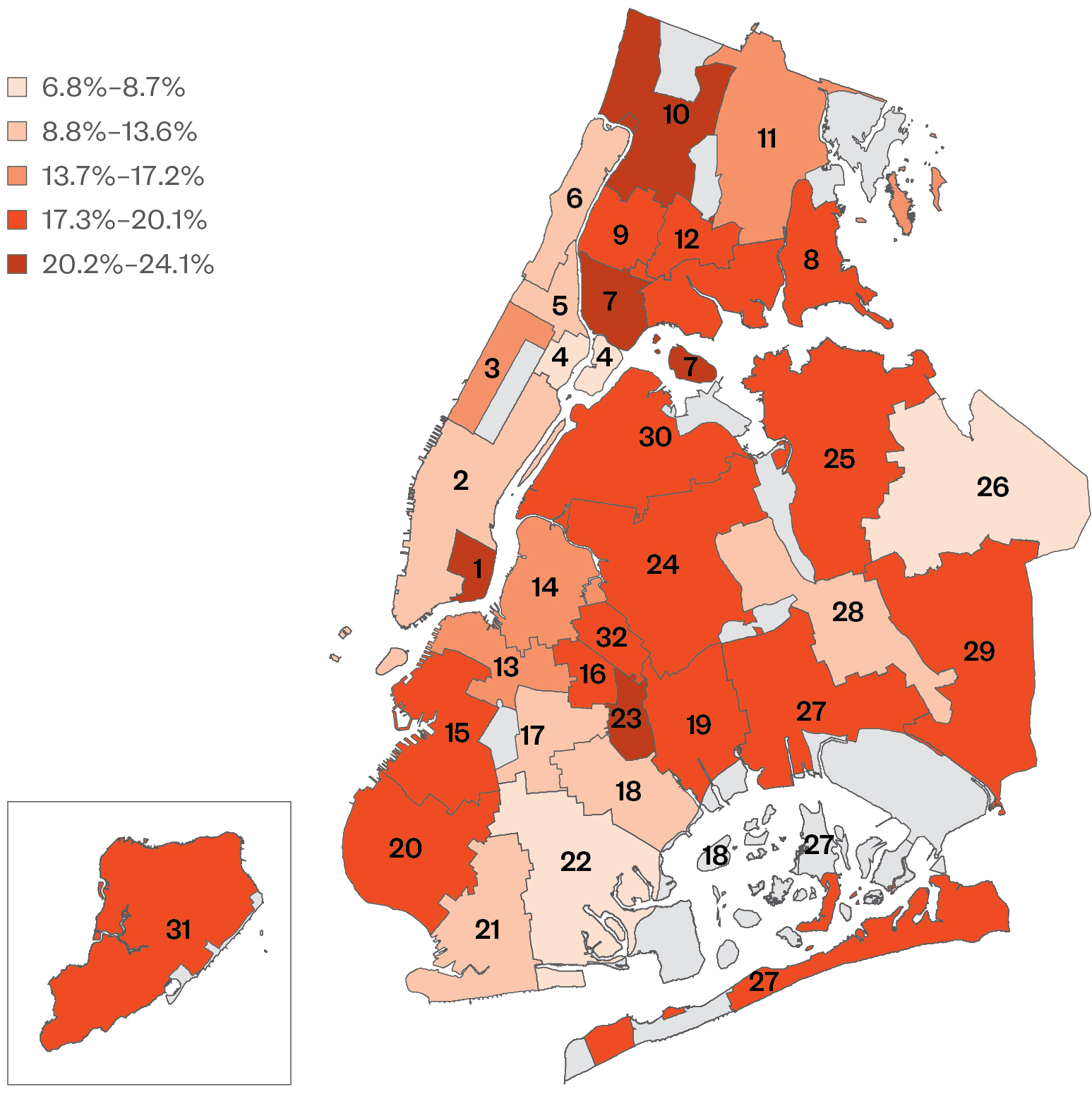

Where Are Homeless Students?

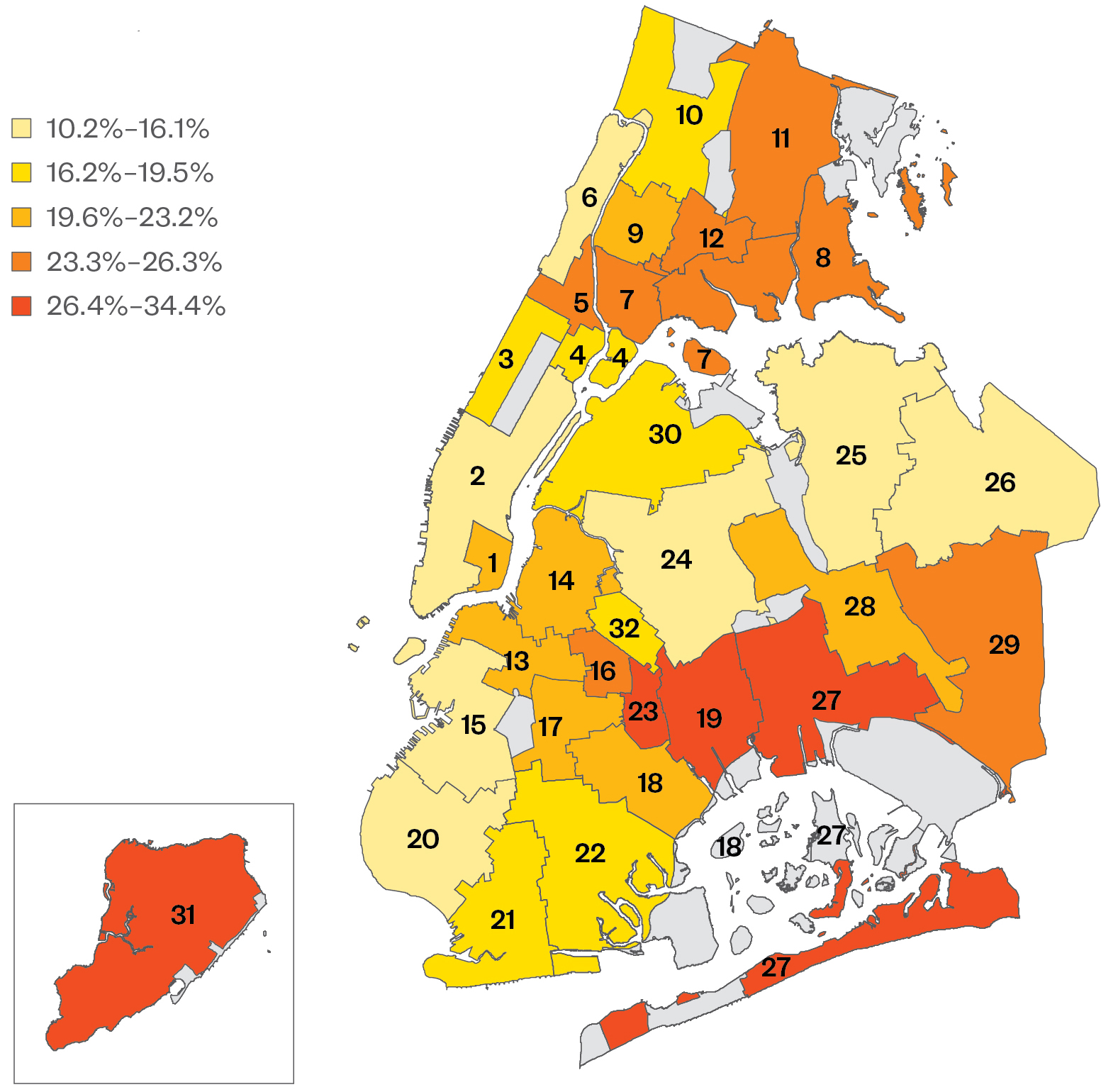

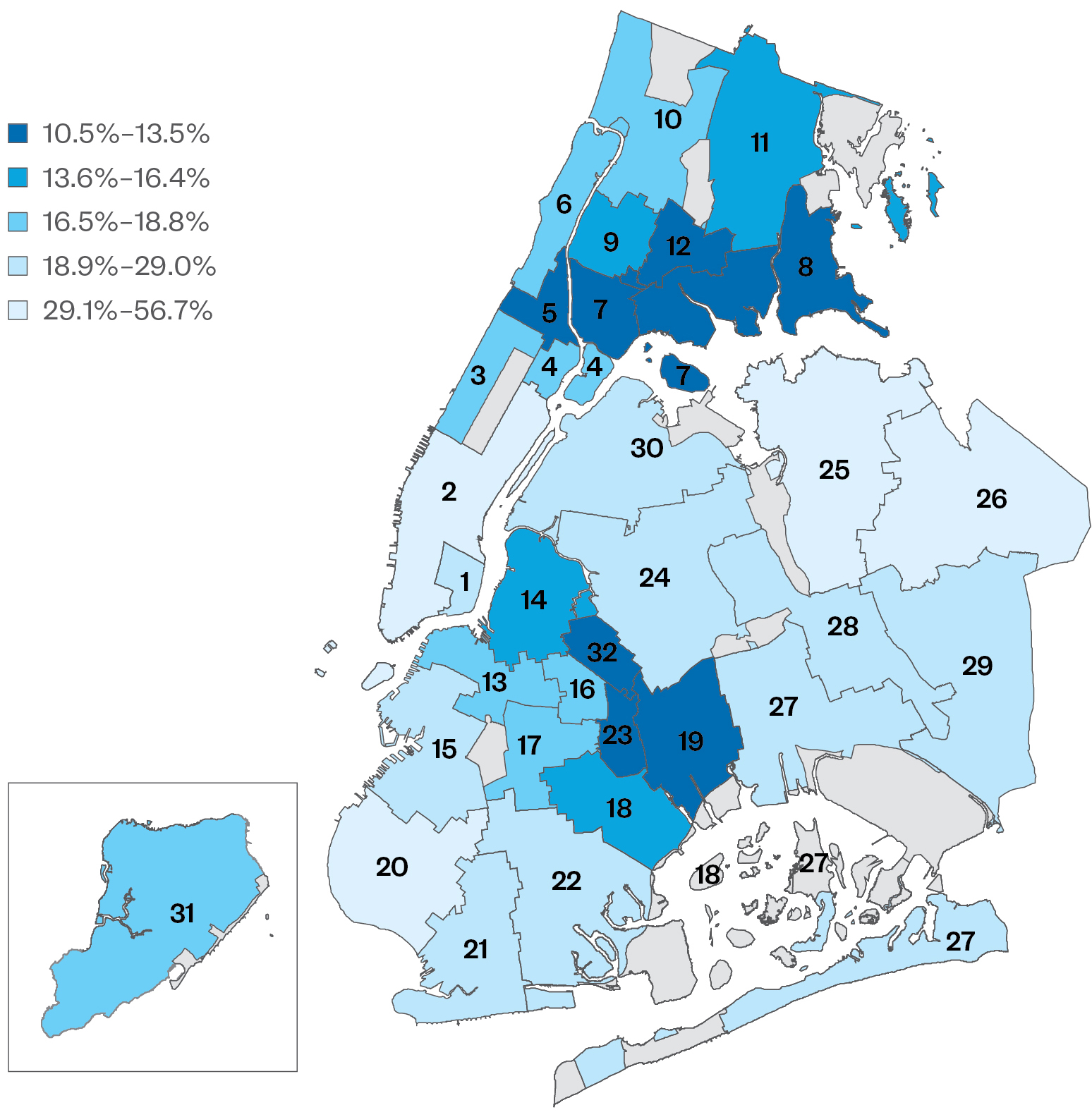

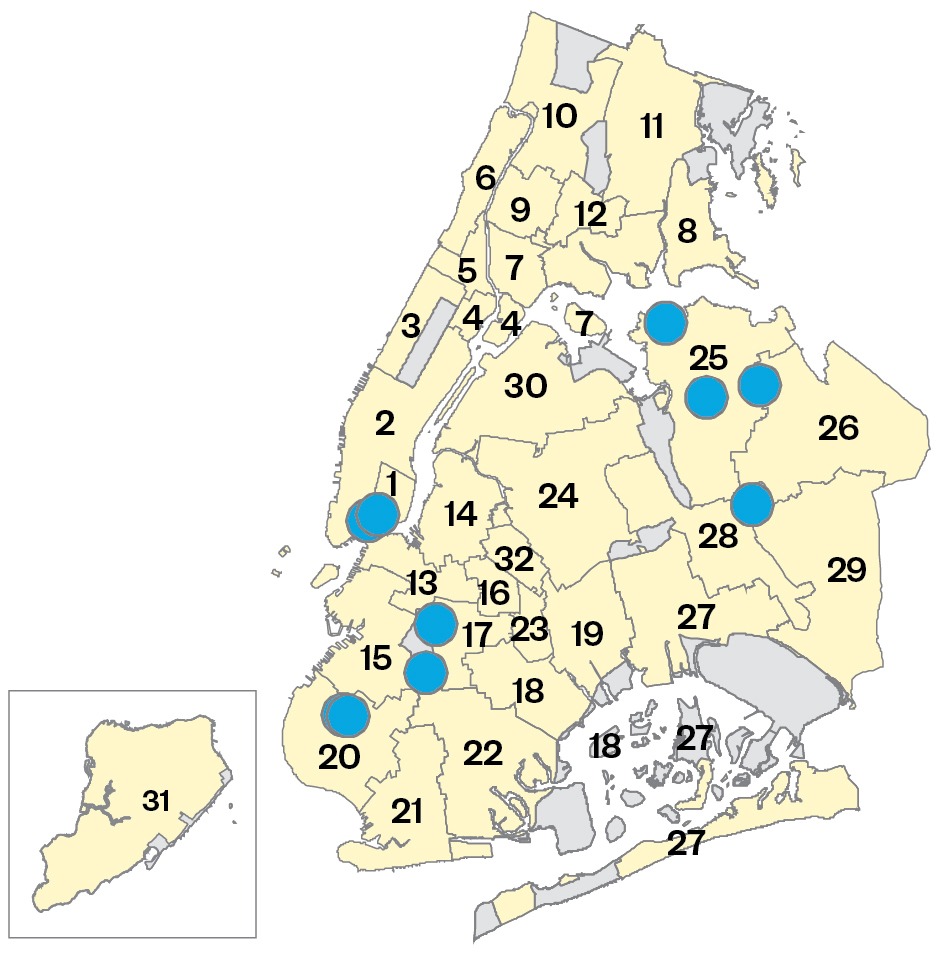

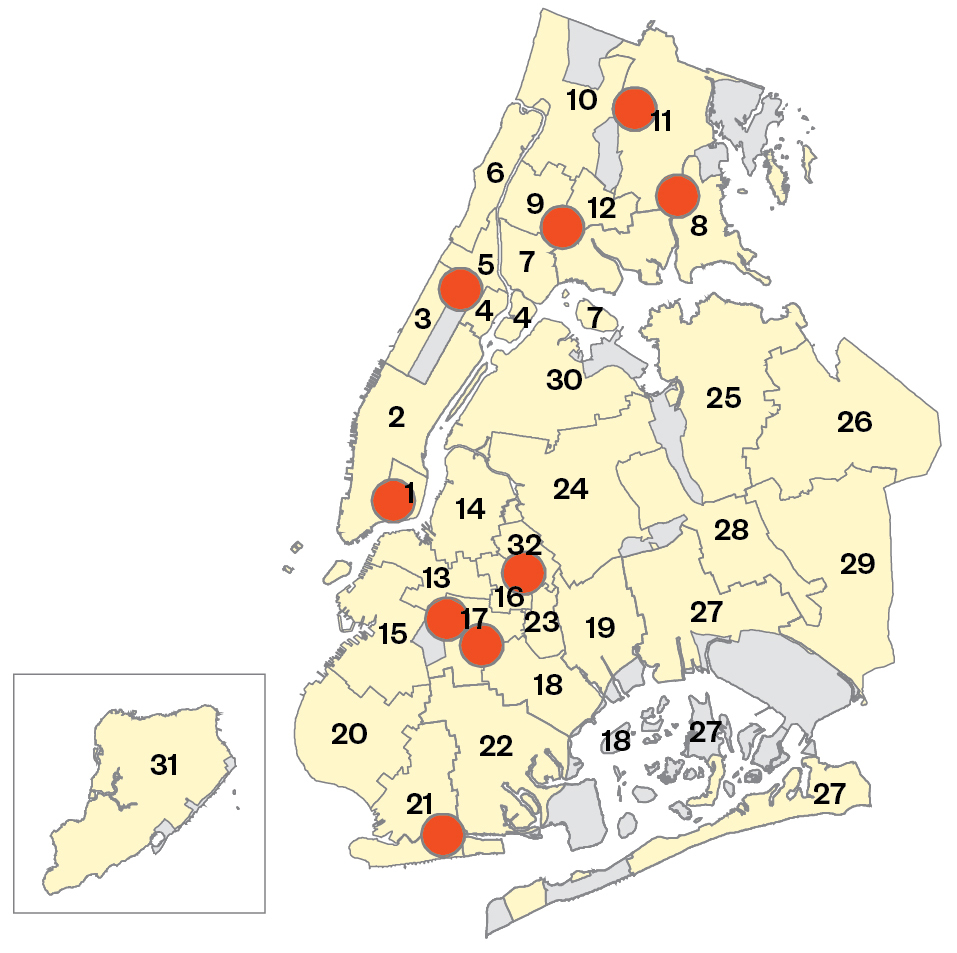

Number and Percent of Students Homeless, by School District

SY 2015–16

Explore Districts at bit.ly/StudentAtlasApp.

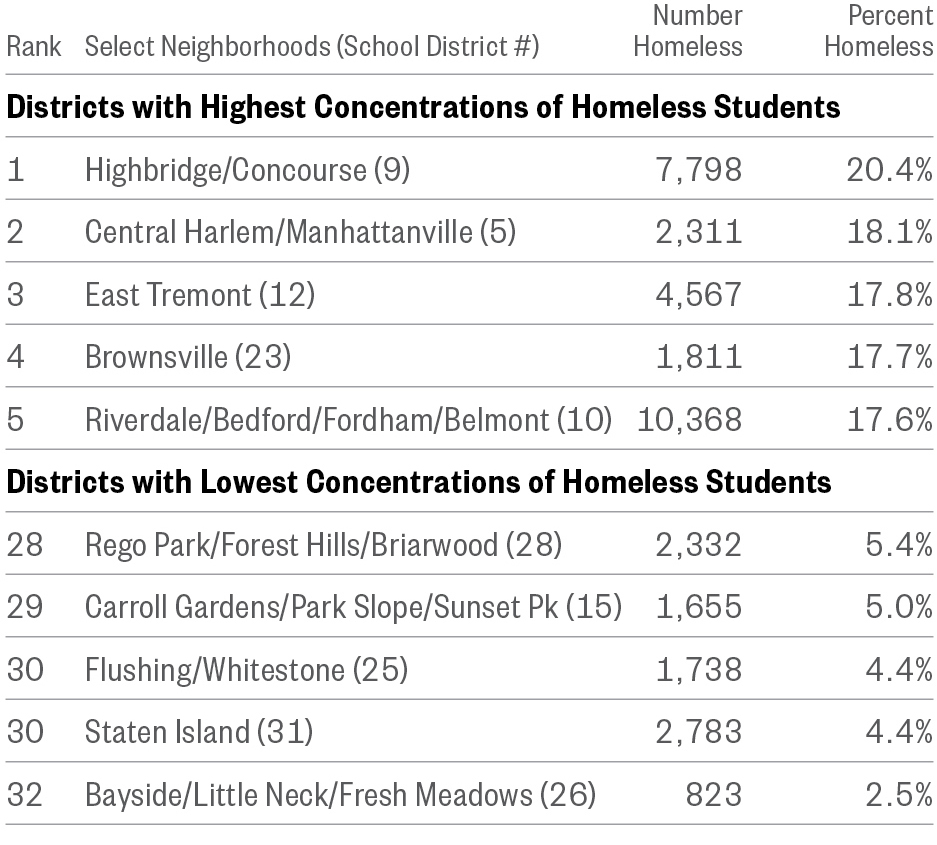

Districts with Highest and Lowest Concentrations of Homeless Students

SY 2015–16

Note: Data are by school district and do not include schools in non-geographic districts.

- An average of nine percent of New York City public school students were homeless in one year. This ranged from a low of 2.5% in Queens’ Bayside to a high of 20% in the Bronx’s Highbridge/ Concourse. (Districts 26 and 9)

- Riverdale/Bedford in the Bronx continues to have the largest number of homeless students citywide (over 10,000). (District 10)

- Bayside in Queens ranks lowest citywide for both the percent of students homeless and the overall number of homeless students (823).

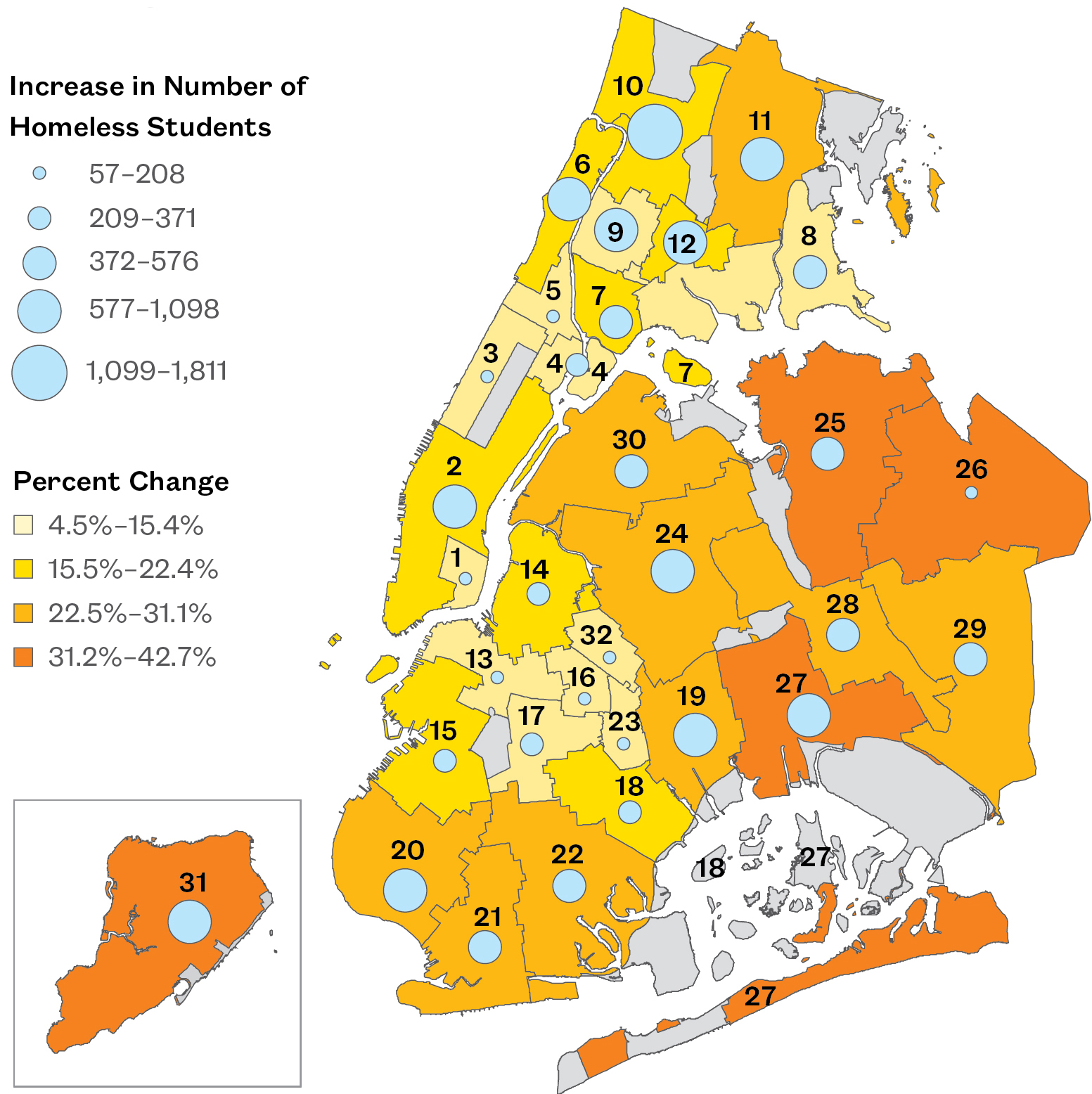

Where Is Homelessness Growing?

Percent Increase in Student Homelessness, by School District

SY 2014–15 to SY 2015–16

Note: Data are by school district and do not include schools in non-geographic districts.

Explore Districts at bit.ly/StudentAtlasApp.

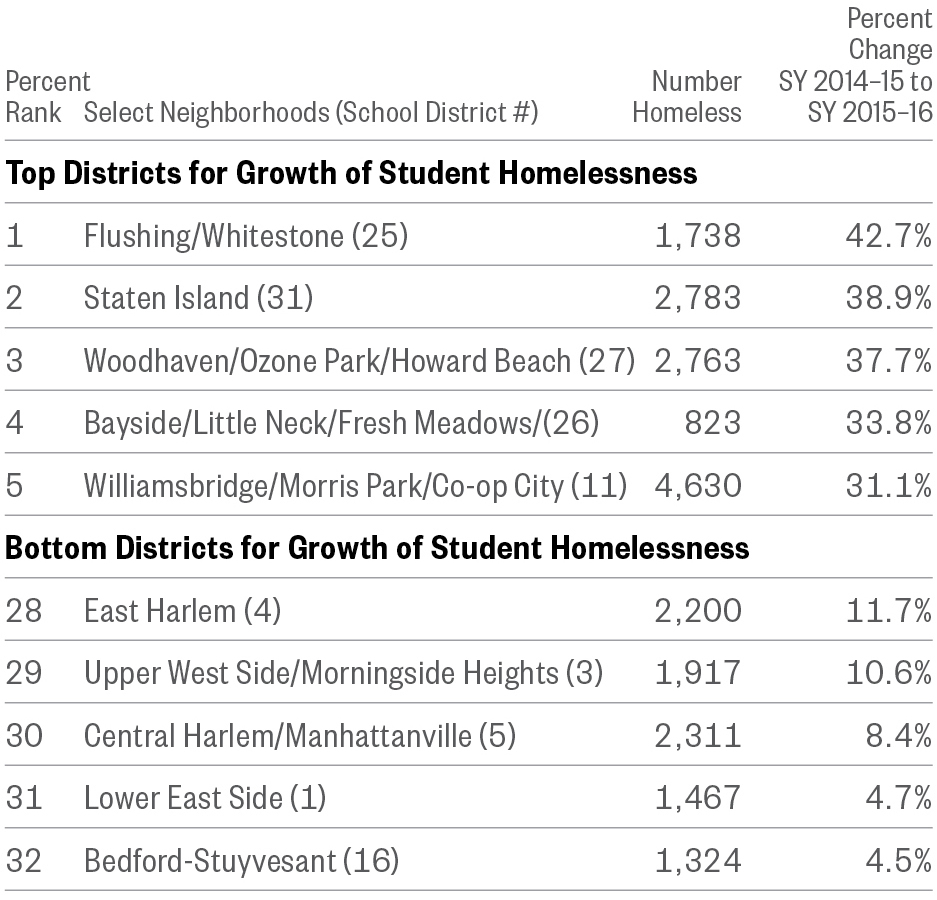

Growth of Student Homelessness

SY 2014–15 to SY 2015–16

- Homelessness increased in every school district in New York City between SY 2014–15 and SY 2015–16.

- Riverdale/Bedford in the Bronx saw the largest number increase in student homelessness, with an increase of more than 1,800 students in one year. (District 10)

- Both Flushing in Queens and Staten Island saw substantial growth in homelessness from the prior year, with increases of at least 520 homeless students each. This represented a 39% growth or more in the numbers of homeless students in those districts. (Districts 25 and 31)

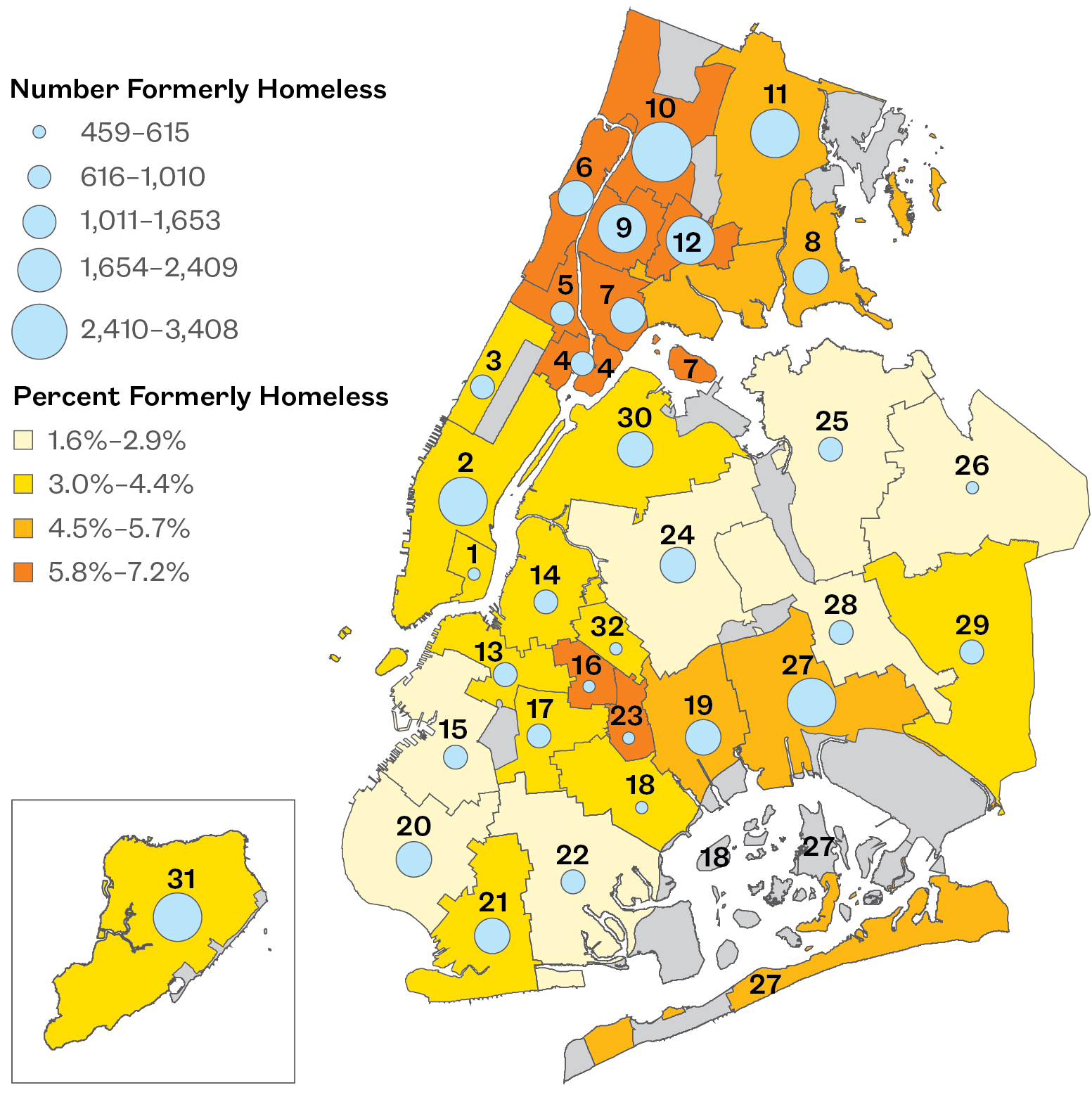

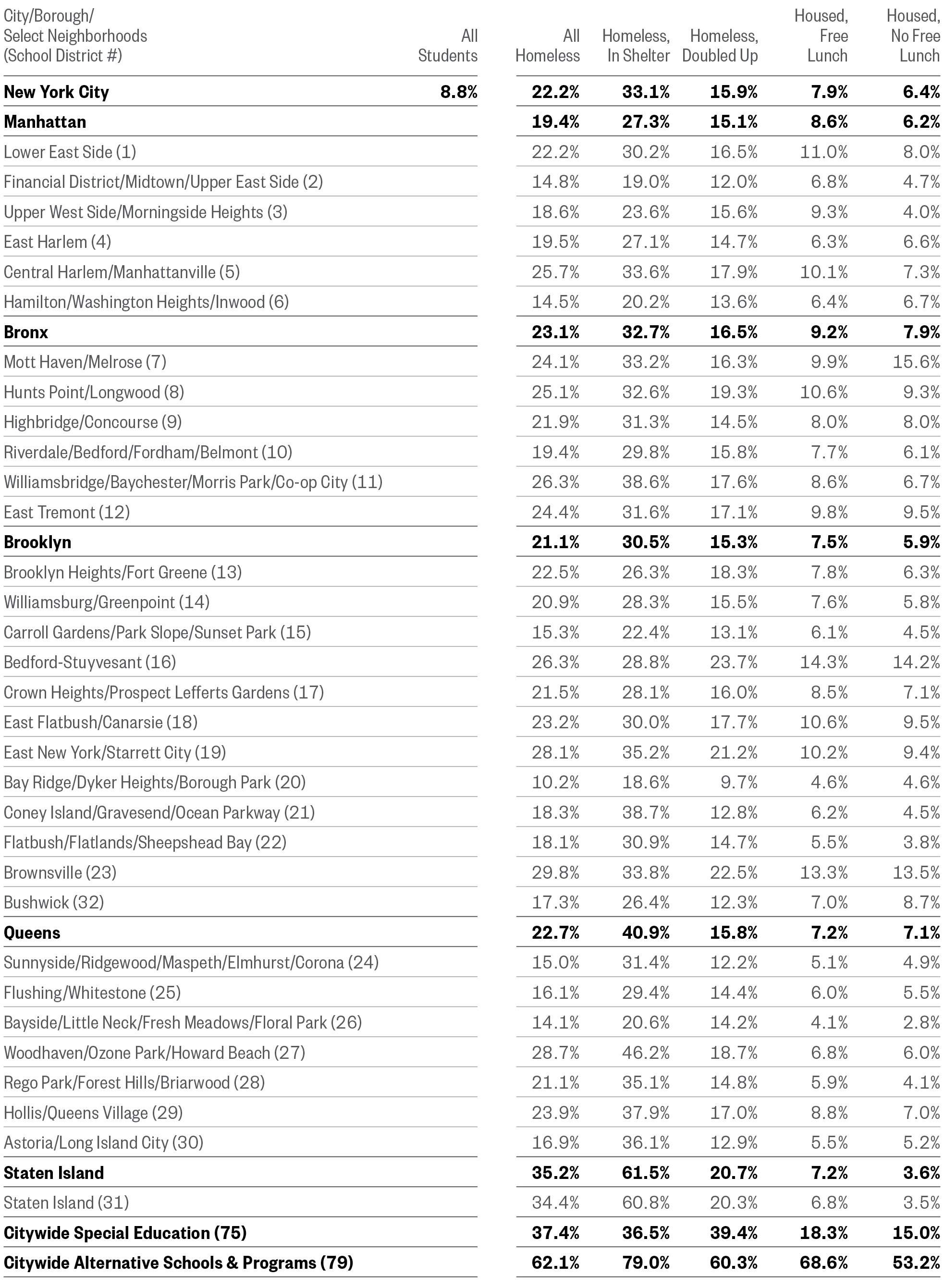

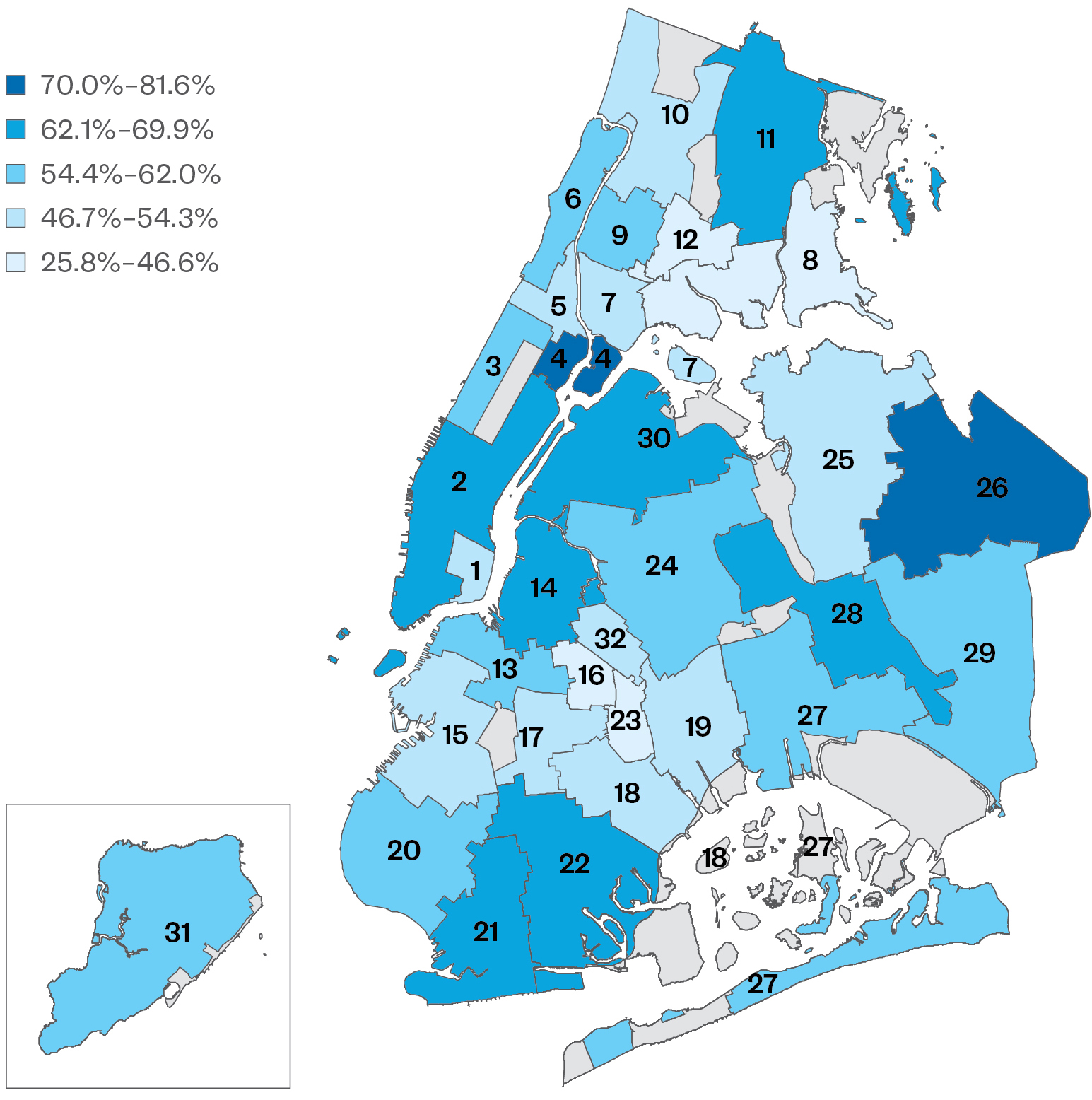

Where Are Formerly Homeless Students?

Number and Percent of Students Formerly Homeless, by School District

SY 2015–16

Note: Data are by school district and do not include schools in non-geographic districts. “Formerly Homeless” includes students who were housed during SY 2015–16 but were homeless at any point during SY 2010–11, SY 2011–12, SY 2012–13, SY 2013–14, and/or SY 2014–15.

Explore Districts at bit.ly/StudentAtlasApp.

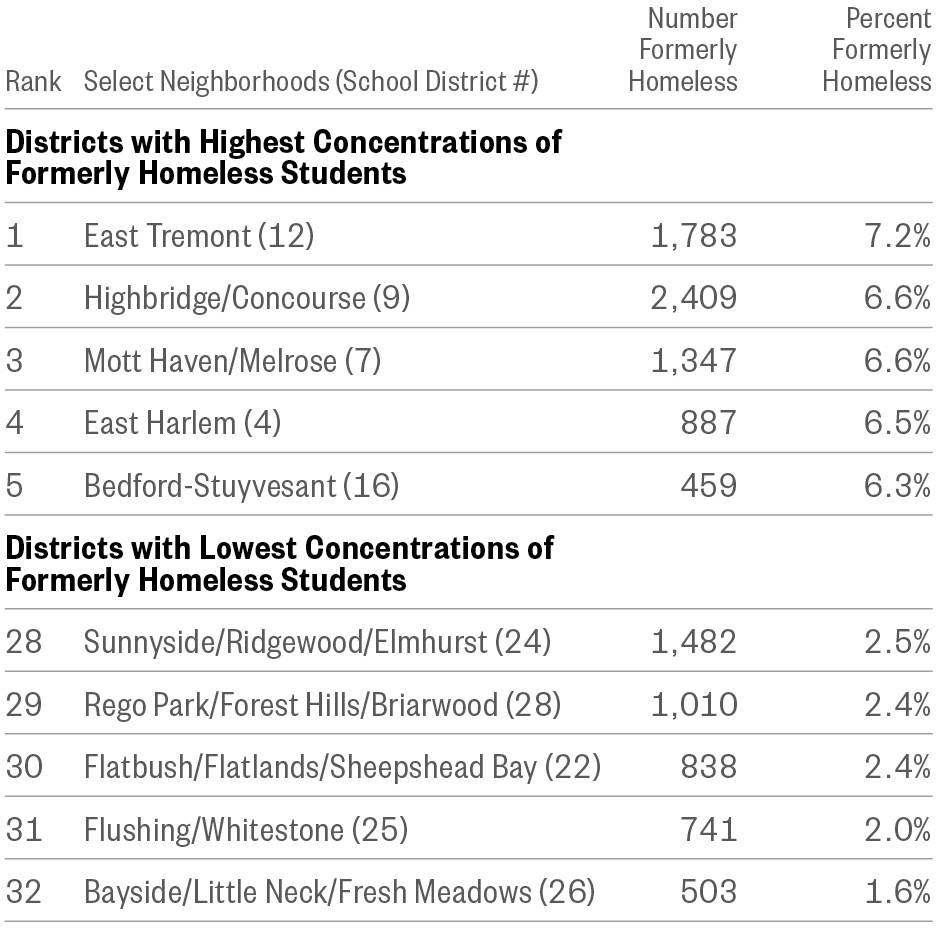

Formerly Homeless Students

SY 2015–16

- In addition to the nine percent of students homeless in SY 2015–16, another four percent were currently housed but had experienced homelessness at some point since SY 2010–11 (formerly homeless).

- In half of the City’s school districts, more than 1,000 students were formerly homeless. The districts with the most formerly homeless students—over 1,650—were located across boroughs, including Manhattan’s Financial District/ Upper East Side; Highbridge, Riverdale, Williamsbridge, and East Tremont in the Bronx; Woodhaven in Queens; and Staten Island. (Districts 2, 9–12, 27, and 31)

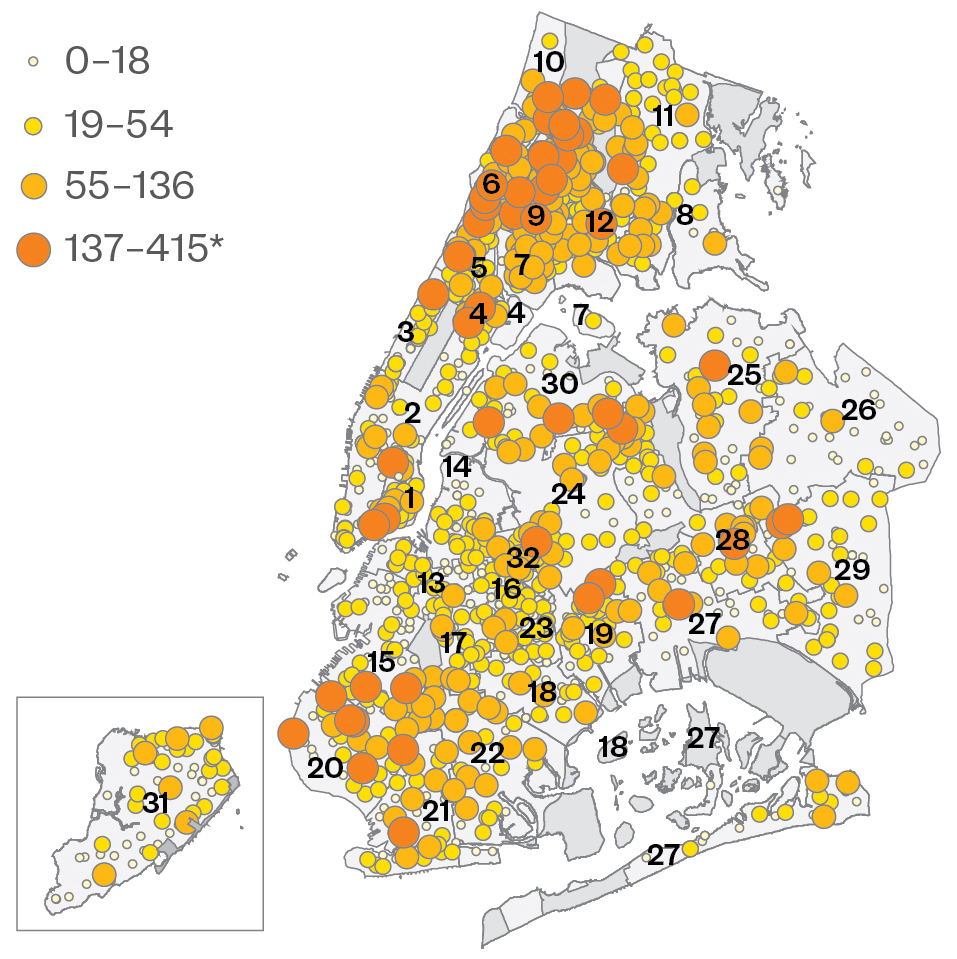

See schools at bit.ly/MapNYCHomelessStudents

- Students living doubled up attended school in every district, including many areas with no family shelters.

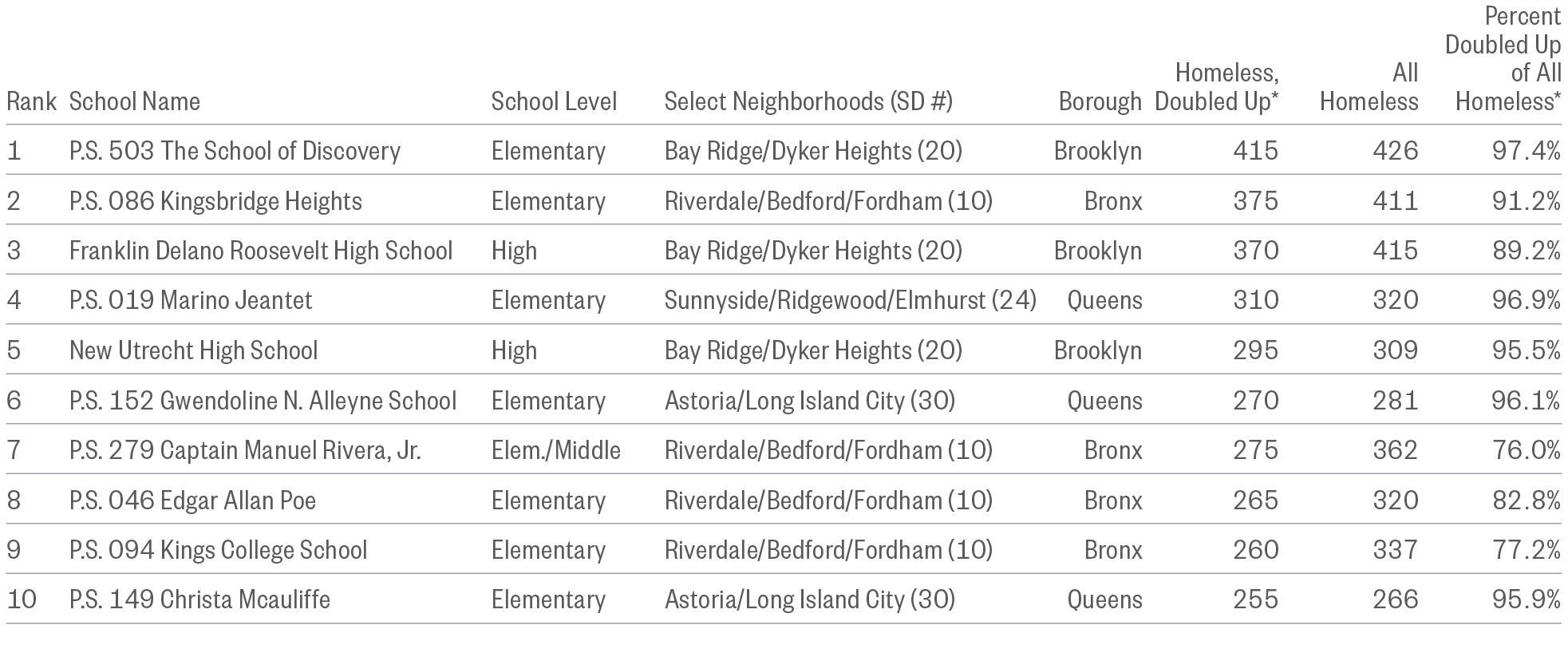

- P.S. 503 The School of Discovery, an elementary school in Bay Ridge, had the largest number (over 415) of doubled-up students enrolled out of all NYC public schools. (District 20)

- More than 250 students living doubled up attended each of the top ten schools for the largest number of doubled-up students in SY 2015–16. These ten schools saw an average 14% growth in the number of students living doubled up from the prior year.

Where Students Living Doubled Up Go to School

Number of Doubled-up Students by School

SY 2015–16

See schools at bit.ly/MapNYCHomelessStudents

Top 10 Schools for Students Living Doubled Up

*Numbers of doubled-up students are rounded down in order to protect student privacy and adhere to the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act.

Note: Data include schools in both geographic and non-geographic districts. Data groupings for the map of doubled-up students by school and the map of sheltered students by school are matched for the purpose of comparison. For comparison and readability, number breaks are manually classified to match the 2016 Atlas of Student Homelessness.

- Homeless students living in shelter attended schools in every district, but were clustered in northern Manhattan, the south and west Bronx, and central Brooklyn. This pattern mirrors the locations of City shelters, suggesting that homeless students in shelter often transfer to schools closer to their shelter placement.

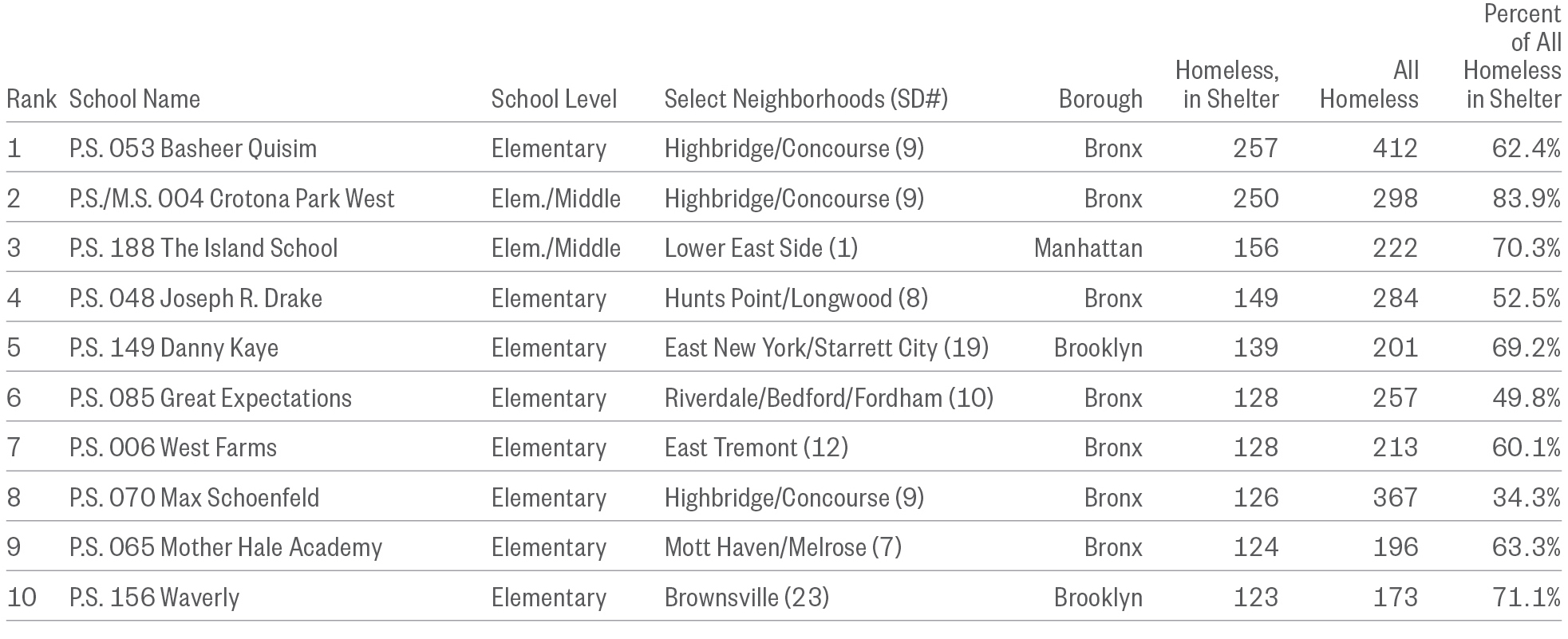

- The top three schools for the largest number of students in shelter are the same as last year. P.S. 053 Basheer Quisim Elementary School in Highbridge/Concourse had the largest number of students living in shelter for the third consecutive year. (District 9)

Where Students Living in Shelter Go to School

Number of Students in Shelter by School

SY 2015–16

See schools at bit.ly/MapNYCHomelessStudents

Top 10 Schools for Students Living in Shelter

Note: Data include schools in both geographic and non-geographic districts. Data groupings for the map of doubled-up students by school and the map of sheltered students by school are matched for the purpose of comparison. For comparison and readability, number breaks are manually classified to match the 2016 Atlas of Student Homelessness.

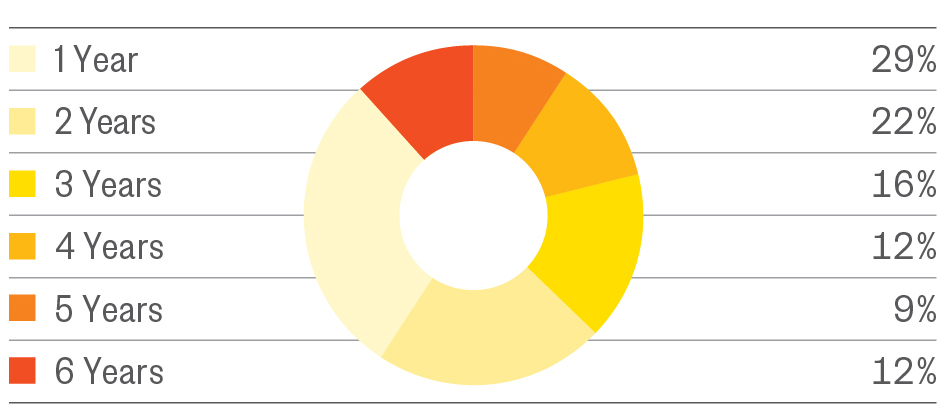

Most Children Are Homeless for More Than One School Year

- Housing instability is a recurring experience for homeless students in New York City. Two-thirds of homeless children in NYC were identified as homeless in more than one school year.

- One-third of homeless students were identified as homeless in at least four of the last six years. Of these students who were repeatedly or continuously homeless, roughly half transitioned housing statuses, living in multiple homeless settings or transitioning into or out of permanent housing at some point.

Housing transitions and repeated experiences of homelessness place students at risk for instability at school.

Number of Years in which Students Have Been Homeless

SY 2015–16

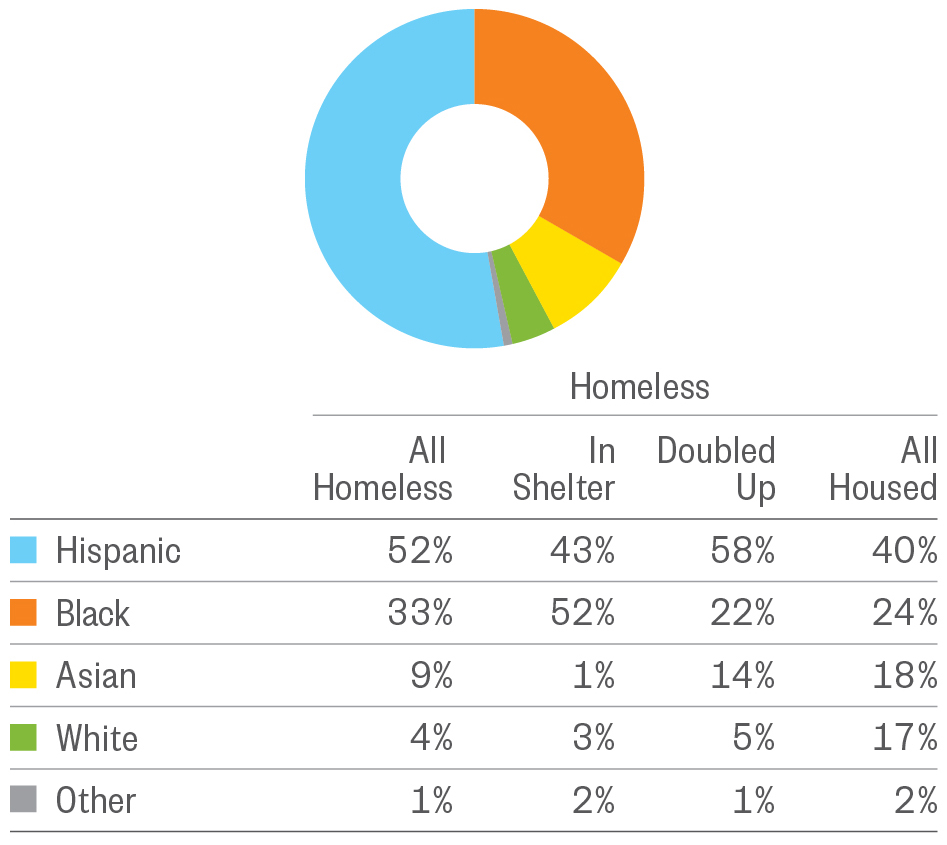

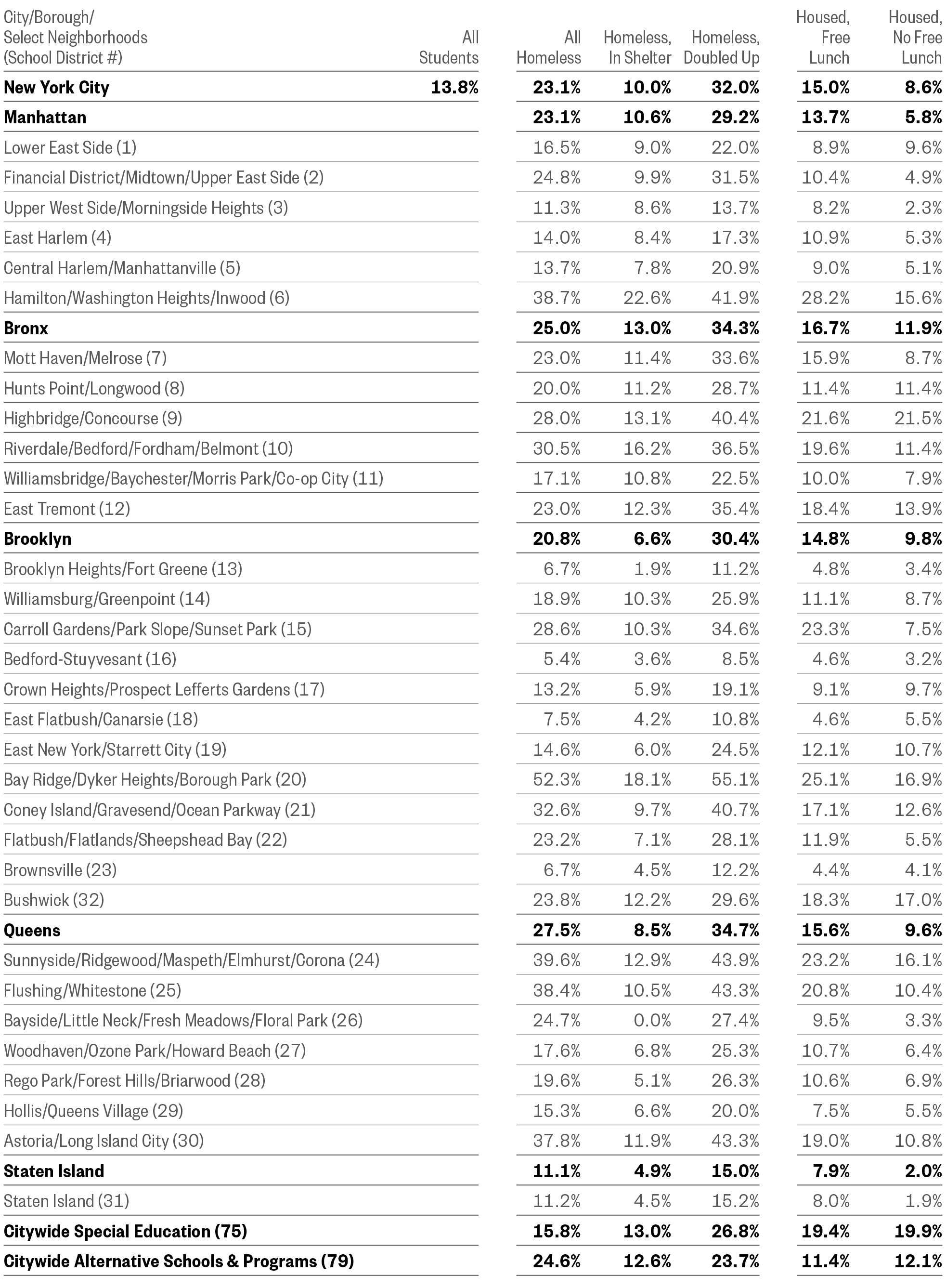

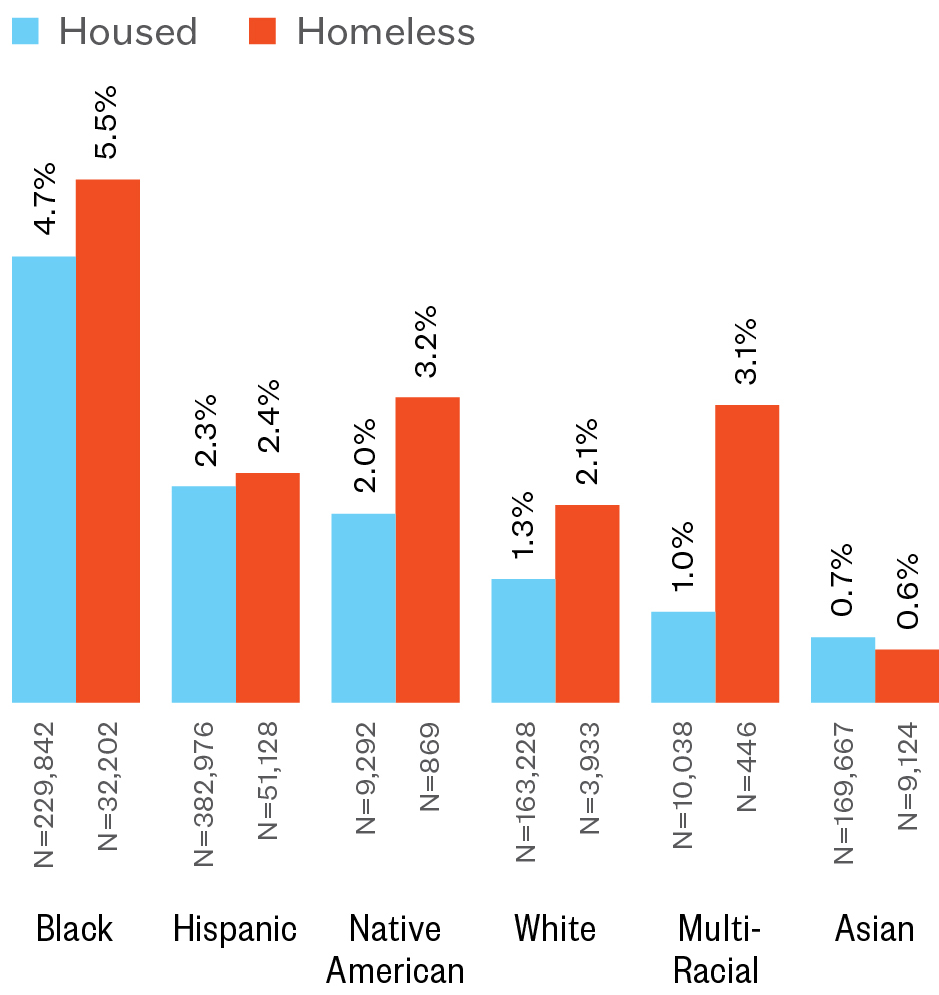

Hispanics and Blacks Are Over-Represented

- One-half of all homeless students in NYC are Hispanic, 25 percent higher than housed students (52% to 40%). Among all Hispanic students enrolled in public schools, 12% were homeless in SY 2015–16.

- One-third of homeless students in NYC were black in SY 2015–16, almost 50 percent higher than housed students (33% to 24%). Among all black students enrolled in public schools, 12% were homeless.

- Students’ race and ethnicity varied by type of homelessness. The majority (52%) of students in shelter were black, while 58% of students living doubled up were Hispanic.

Race and Ethnicity of Homeless Students

SY 2015–16

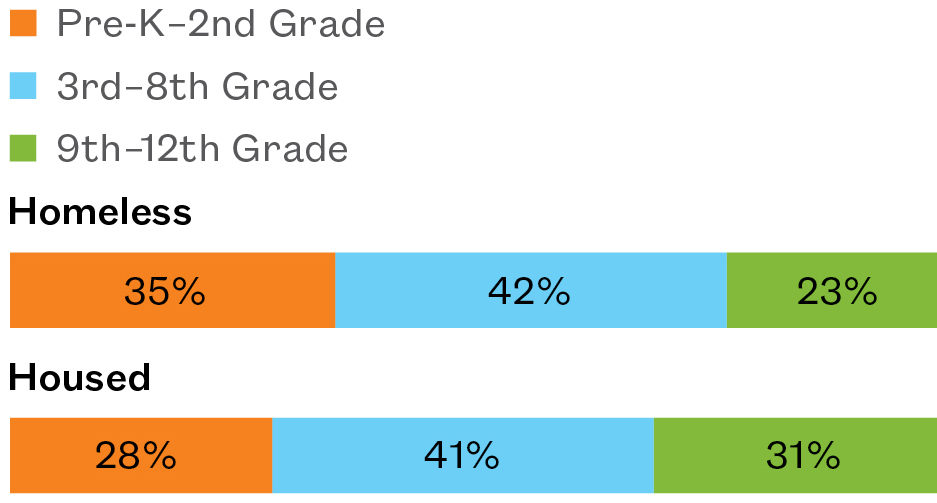

Young Students Are Most At Risk for Homelessness

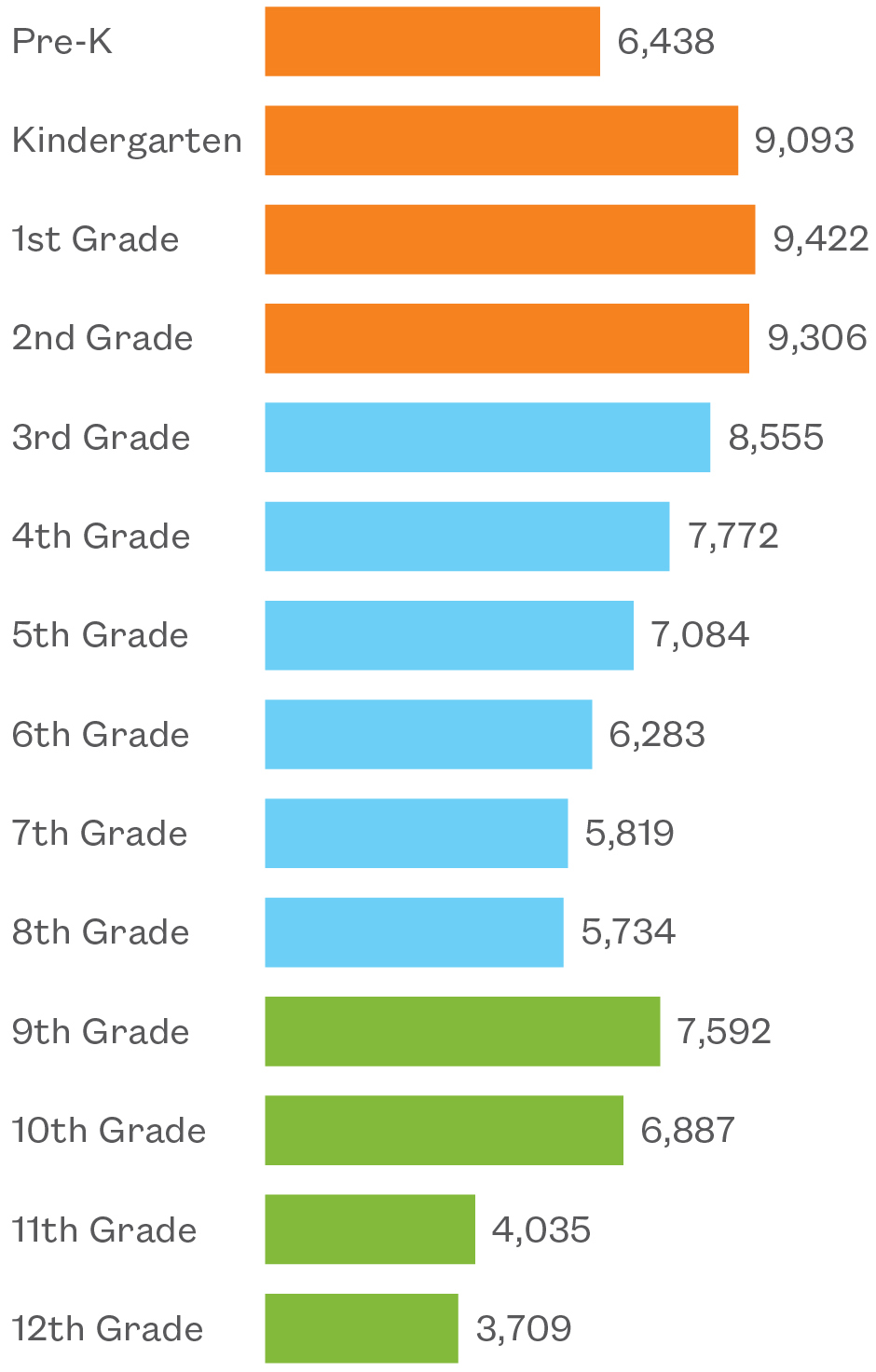

- More than 9,000 homeless children were enrolled in each grade from Kindergarten through second, making these the most common grades by far for homeless students to attend. Housed students follow a different pattern, however, with ninth and tenth grades representing the most common age. The different patterns of enrollment may point to under-identification of homeless students in high school, but also the increased vulnerability and housing instability faced by young families and children.

- Amidst the expansion of Universal Pre-K programs in New York City, pre-K enrollment among homeless students in SY 2015–16 increased by 17% over the prior year. However, the enrollment gap between pre-K and Kindergarten students suggests that over 2,500 homeless children eligible for pre-K were not reached by New York City’s public pre-K programs in SY 2015–16.

As the City prepares to introduce pre-K for all three-year-olds, how can the enrollment gap between housed and homeless students be eliminated in early childhood classrooms?

Homeless Students by Grade Level

SY 2015–16

Number of Homeless Students by Grade Level

SY 2015–16

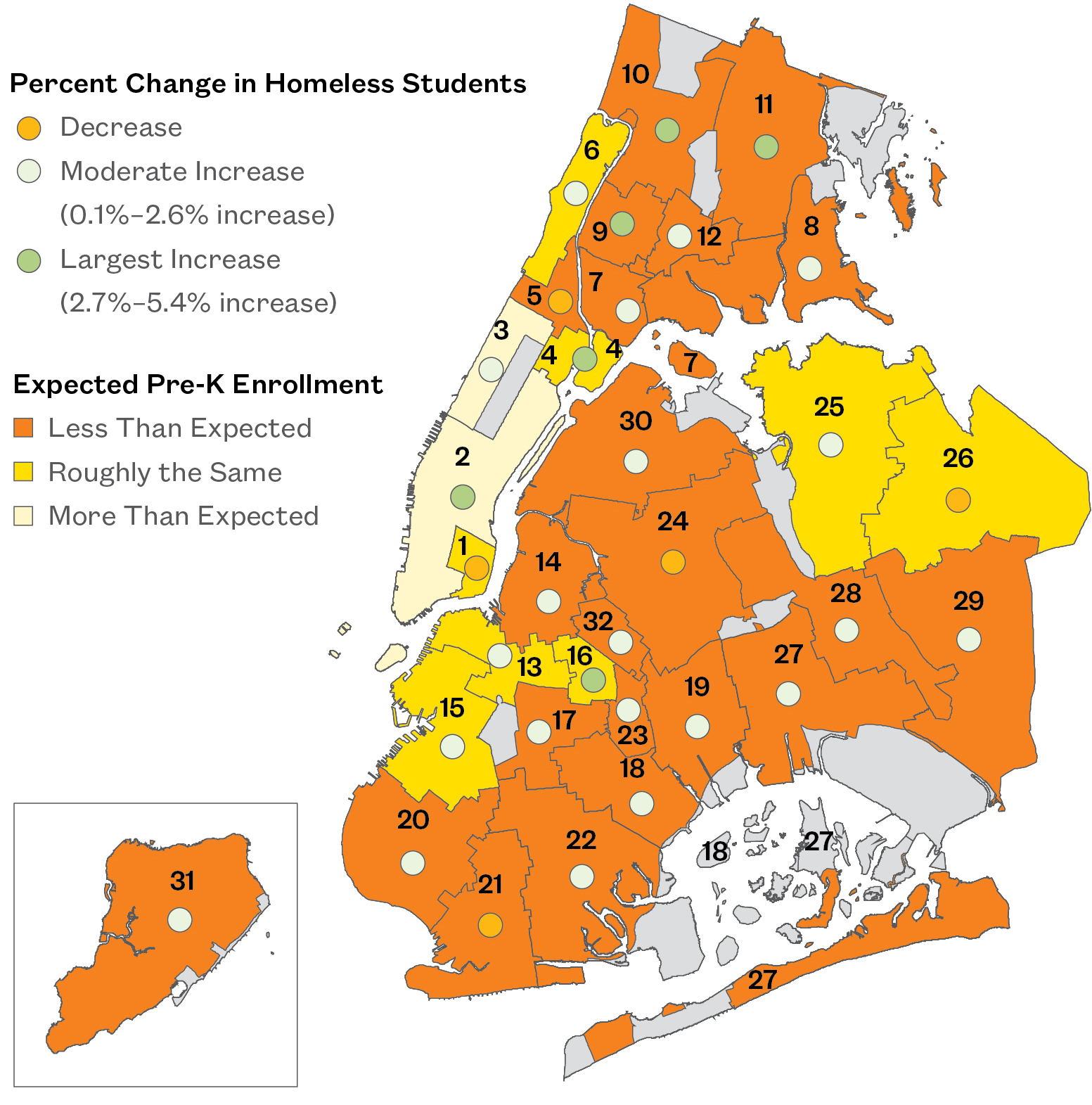

Where Do Students Who Are Homeless Enroll in Pre-K?

Percent of Pre-K Students Who Are Homeless, by School District

SY 2014–15 to SY 2015–16

Explore Districts at bit.ly/StudentAtlasApp.

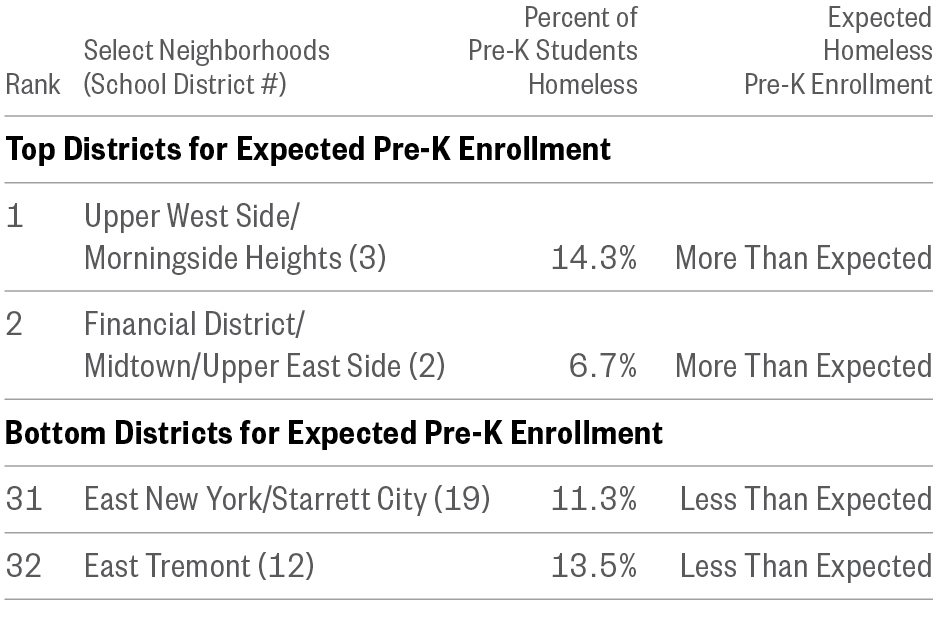

Pre-K Student Homelessness

SY 2015–16

Note: Data are by school district for SY 2015–16 and do not include schools in non-geographic districts. Percentage groupings for the map of homeless students by district and the map of homeless pre-K students by district are matched for the purpose of comparison. Expected pre-K enrollment refers to the comparison between the percentage of pre-K students homeless and the percentage of Kindergarteners and first graders who were homeless. Districts that enrolled roughly the same had enrollment of the two groups within two percentage points of each other; those that enrolled more or less than expected saw at least a two percentage-point enrollment difference.

- The City has succeeded in increasing pre-K enrollment among children who have been homeless, with a 17% increase from SY 2014–15 to SY 2015–16.

- Central Harlem in Manhattan, Coney Island in Brooklyn and Sunnyside in Queens saw a decrease in pre-K enrollment of homeless students, yet enrolled a lower rate of pre-Kindergarteners than would be expected based on the percentage of other young homeless students. (Districts 5, 21, and 24)

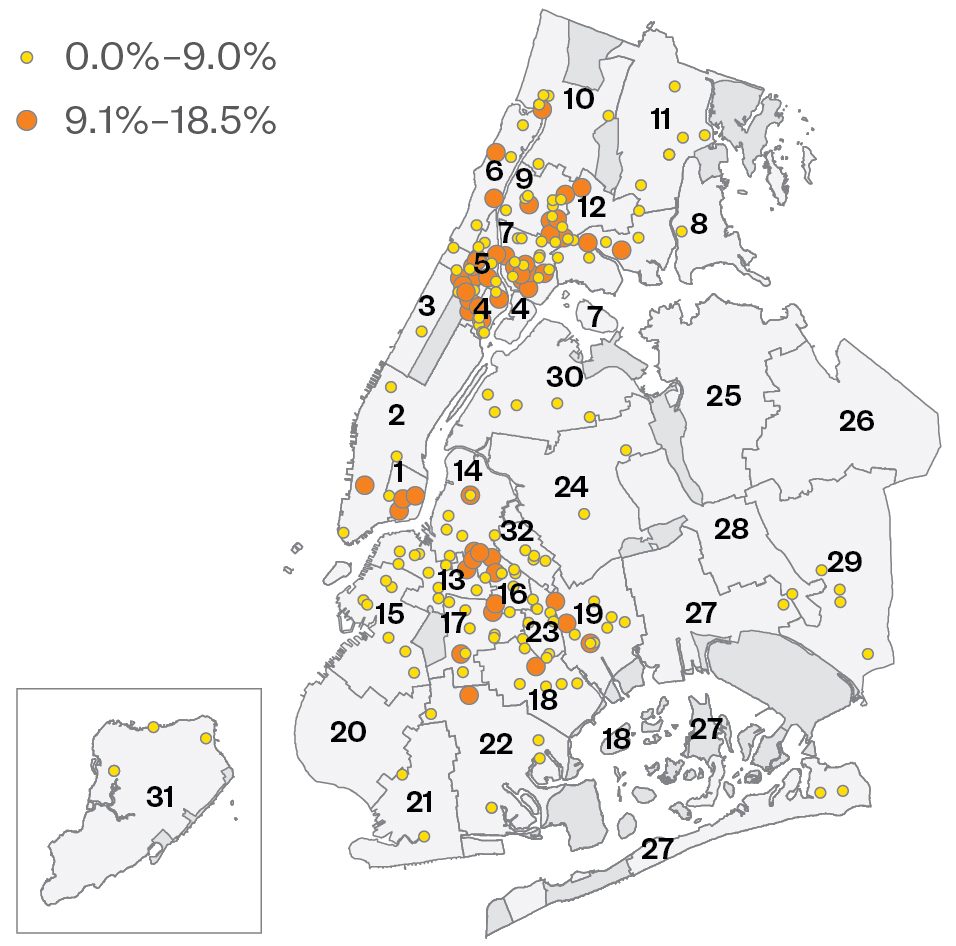

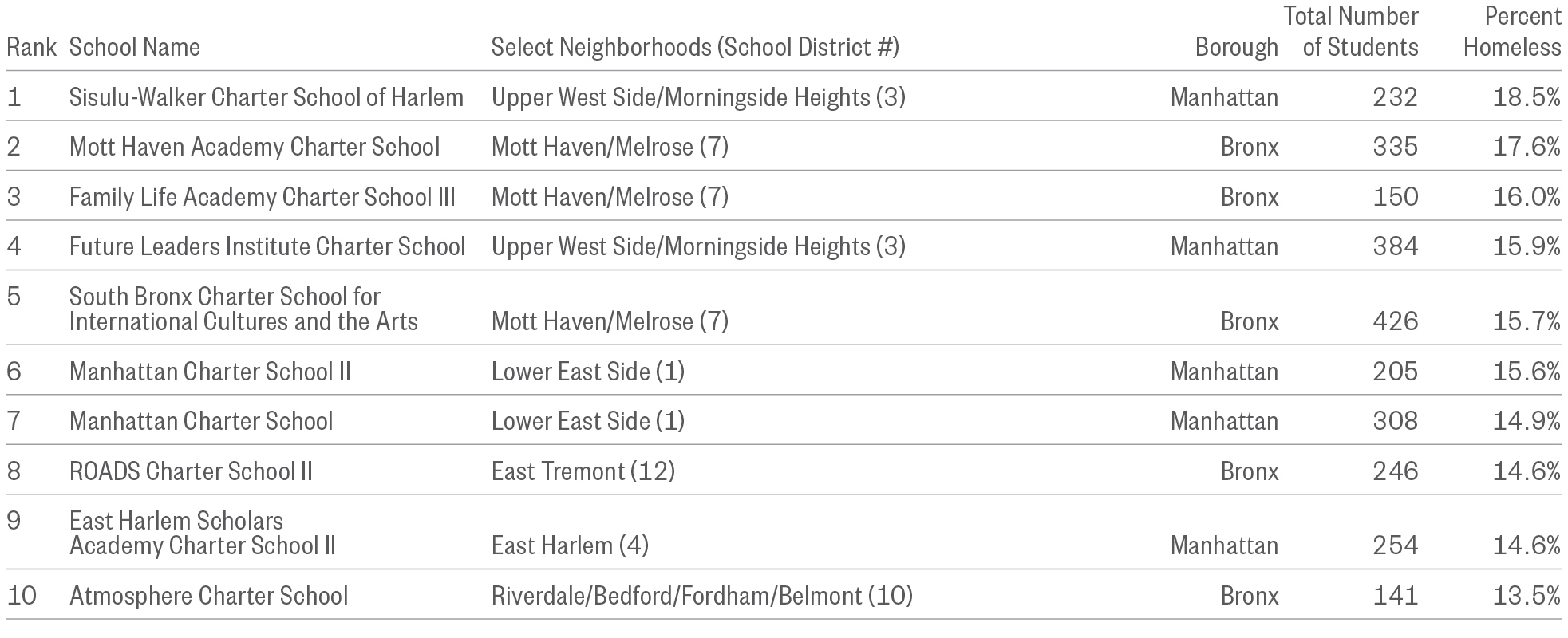

Homeless Students in Charter Schools

- On average, 6.6% of students in New York City charter schools were homeless in SY 2015–16—three points lower than the rate among students in public schools (9.3%).

- This ranged from fewer than five homeless students in 10 charter schools citywide to a high of 19% of students in Sisulu-Walker Charter School of Harlem.

- Charter schools with the highest rates of student homelessness (9%–18.5%) were clustered in the districts where the most homeless students attend public schools. By contrast, in public schools in those districts, up to 48% of students were homeless.

The lower enrollment rate of homeless students in charter schools raises questions about enrollment opportunities for students who are experiencing housing instability.

What Charter Schools Do Homeless Students Attend?

Percent of Homeless Students by Charter School

SY 2015–16

See schools at bit.ly/MapNYCHomelessStudents

Top 10 Charter Schools for Homeless Students

Note: While the total number of homeless charter school students is reported to the State annually, more detailed information on the outcomes of homeless students attending charter schools is not publicly available. School districts represent where charter schools are physically located and do not relate to the school’s administration.

Download Section 1 PDF

To explore homelessness in New York City schools, try our interactive map.

To learn more about the educational outcomes of homeless New York city students, try our Student Atlas app.

Return to top.

Section 2

Housing Instability Undermines School Stability: Mid-Year Transfers and Chronic Absenteeism

We have a really high population of students that are in temporary housing. I think a lot of students in temporary housing get lost in the cracks, because they are not always seen as homeless—but they are. They are doubled up or constantly moving around from home to home. They might not have adequate furniture or a desk where they are living. Or if Mom gets in a fight with her cousin, they could be out. It’s a lot of anxiety and stress for the kids. That comes out in all sorts of ways, behaviorally and academically.

—Social Work Director, Partnership with Children,working in Brooklyn public schools

Obviously there’s a relationship between chronic absenteeism and homelessness. … The students are underperforming. … They’re working on trying to reduce the absenteeism, but you know there are a lot of variables in terms of homelessness that are impacting the kids getting to school.

—Former Principal, Community School in Brooklyn

The New York City Department of Education has placed great emphasis on improving attendance and school stability for all students, including those living in homeless shelters and other temporary housing. These efforts are much needed, as students who experience housing instability are at a far greater risk for transferring schools and being absent. Mid-year school transfers destabilize students’ educations, disrupting their learning and removing them from teachers, classmates, and other school connections. Furthermore, transferring school mid-year heightens students’ risk for chronic absenteeism—one of the strongest predictors of educational achievement and graduation outcomes. Identifying students who are most vulnerable to school instability is critical to ensuring that homeless students are able to attend school and succeed at the same rates as their classmates.

What’s New?

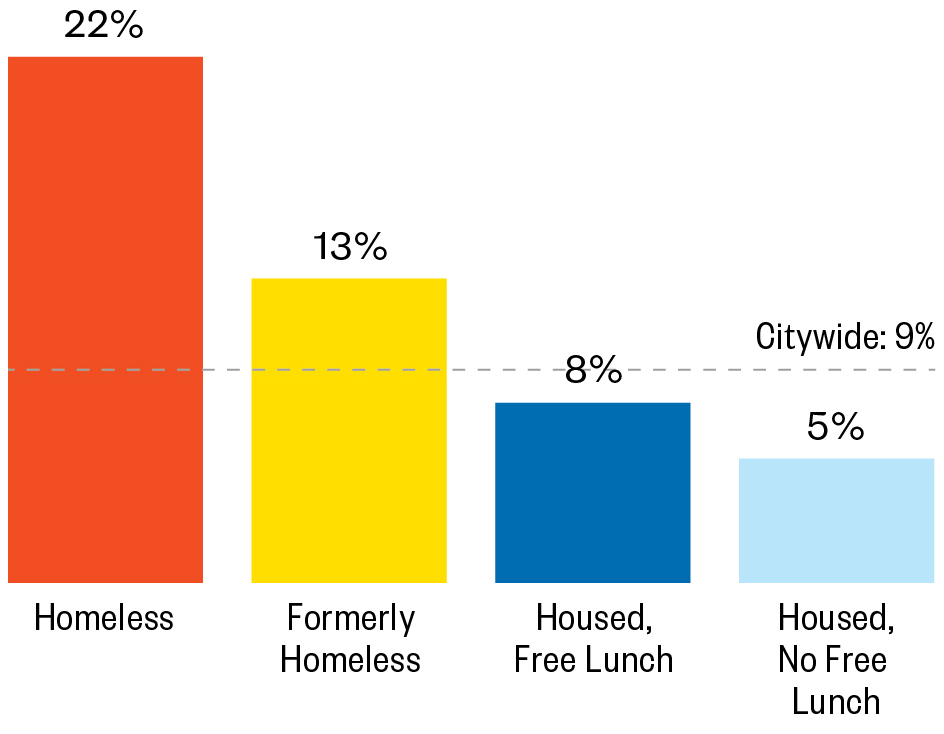

- Overall, 22% of homeless students transferred out of their school mid-year in SY 2015–16, over two times the citywide rate.

- Disparities in transfer rates and chronic absenteeism persist even after homeless students become re-housed.

- Nine of the ten schools with the most homeless students transferring in mid-year were located in Hunts Point, Highbridge/Concourse, and Riverdale in the Bronx—areas of the city with the most family shelters. (Districts 8, 9, and 10)

Policy Considerations

- Continued gaps in school stability and attendance for formerly homeless students highlight the lasting impact of homelessness on a family’s life—and the need for continued supports that do not end once a student becomes housed.

- Schools and shelters should use available data to further coordinate supportive services between schools and shelters, creating more opportunities for effective attendance, transportation, and other school supports.

Mid-Year School Transfers

- More than one in every five (22%) homeless students transferred schools mid-year in SY 2015–16—nearly three times the rate of low-income housed students (8%) and four times that of housed students who were not (5%).

- Formerly homeless students transferred mid-year at a nearly 50 percent higher rate than their low-income housed classmates and close to three times the rate of their non-low-income housed classmates (13%, 8%, and 5%).

Mid-Year School Transfer Rate

SY 2015–16

Note: “Formerly Homeless” includes students who were housed during SY 2015–16 but were homeless at any point during SY 2010–11, SY 2011–12, SY 2012–13, SY 2013–14, and/or SY 2014–15.

Note: “Formerly Homeless” includes students who were housed during SY 2015–16 but were homeless at any point during SY 2010–11, SY 2011–12, SY 2012–13, SY 2013–14, and/or SY 2014–15.

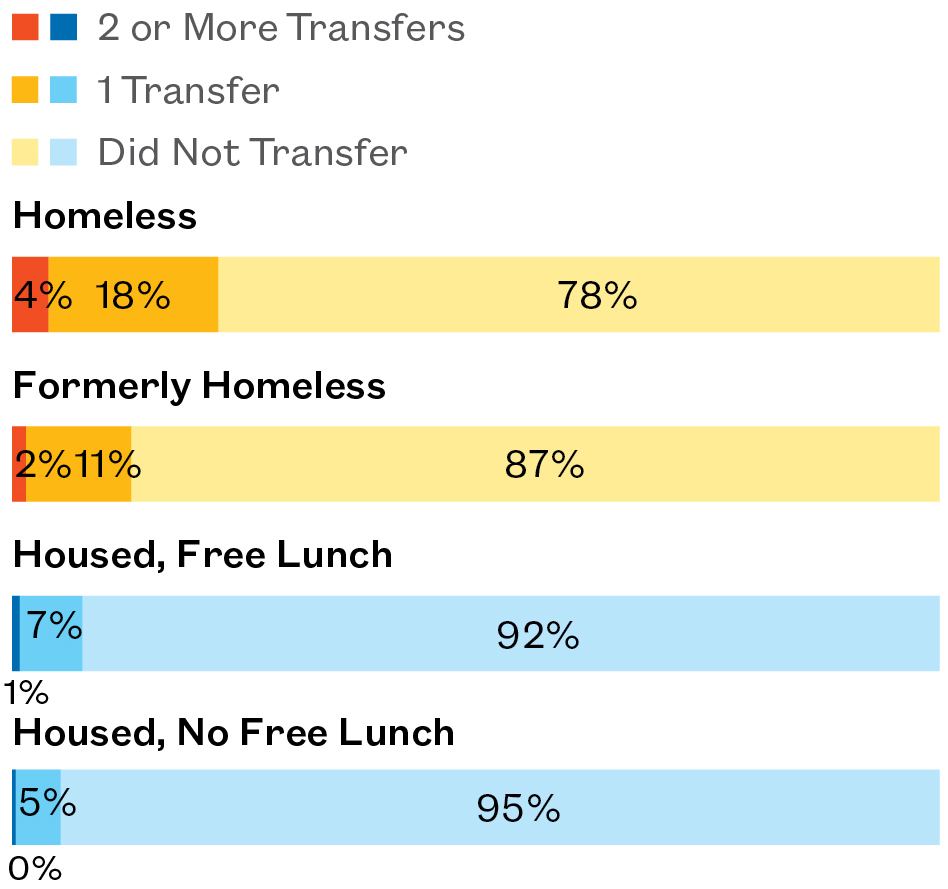

- Not only did homeless and formerly homeless students transfer schools mid-year at a higher rate, but they experienced more extreme levels of school instability as well. Four percent of homeless students and two percent of formerly homeless students—3,900 and 600 students respectively—transferred two or more times in the middle of SY 2015–16, compared to 1% of housed, low-income students and 0.4% of housed students who were not.

Disparities in transfer rates persisted even after homeless students became housed. This highlights the lasting impact of homelessness on a family’s life and the need for continued supports that do not end once a student becomes housed.

Number of Mid-Year Transfers, by Housing Status

SY 2015–16

Note: Mid-year transfers refer to when students transferred into or within their school district during the 2015–16 school year. “Formerly Homeless” includes students who were housed during SY 2015–16 but were homeless at any point during SY 2010–11, SY 2011–12, SY 2012–13, SY 2013–14, and/or SY 2014–15.

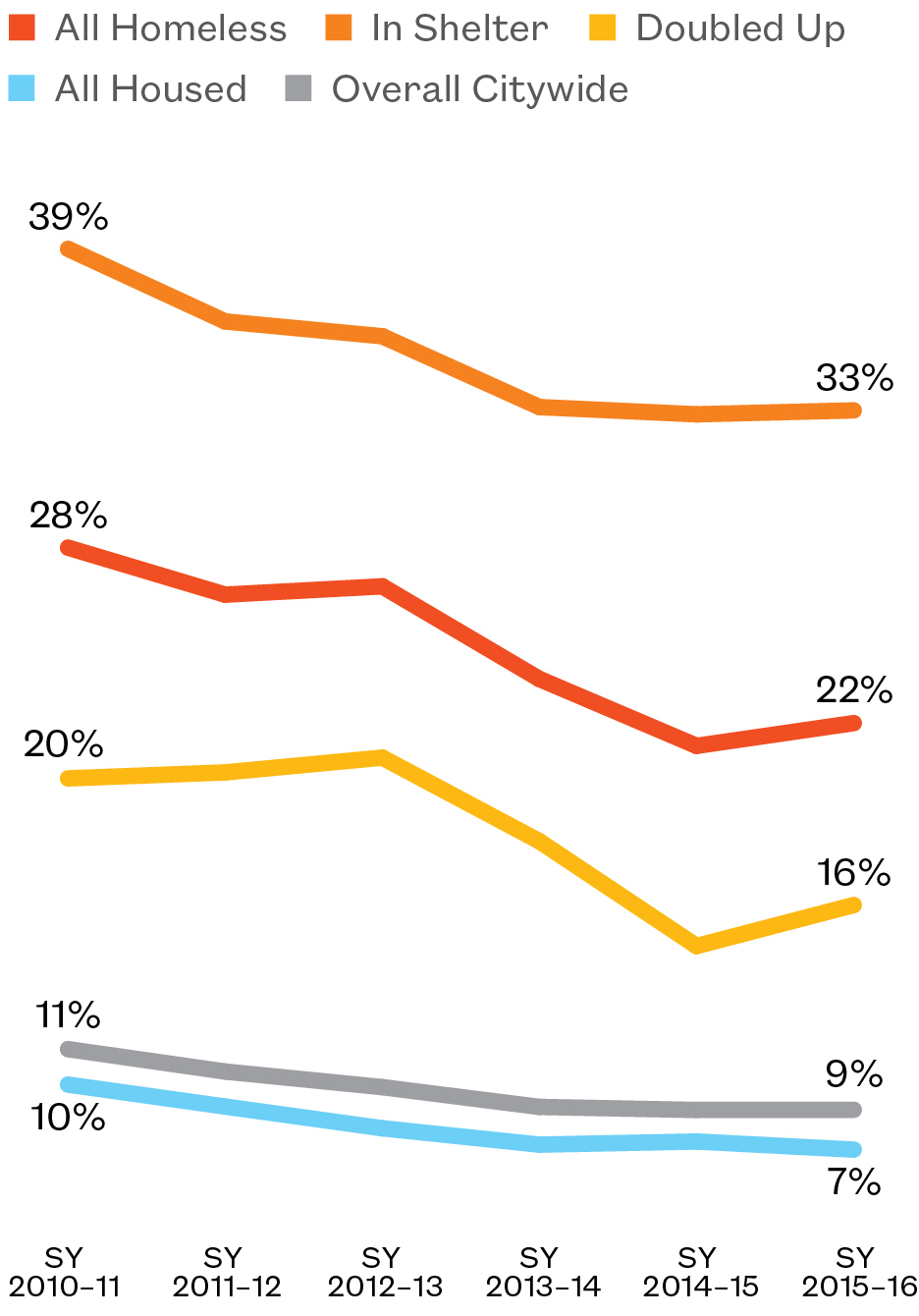

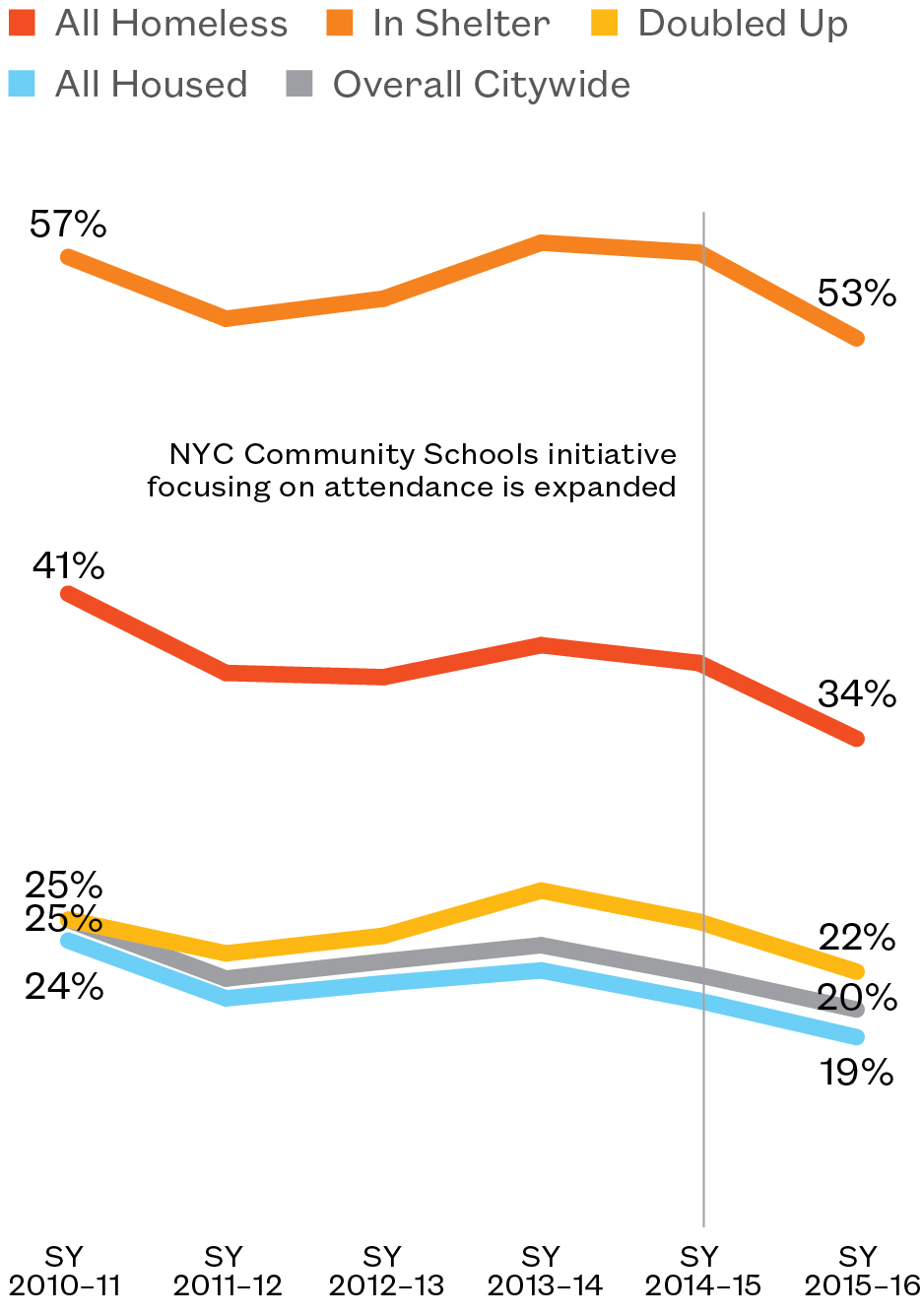

- While the citywide transfer rates for both homeless and housed students have declined since SY 2010–11, a significant gap persists (22% to 7%).

- The mid-year transfer rate declined across housing statuses, with decreases in the rates for both doubled-up and sheltered students (20%–16% and 39%–33%).

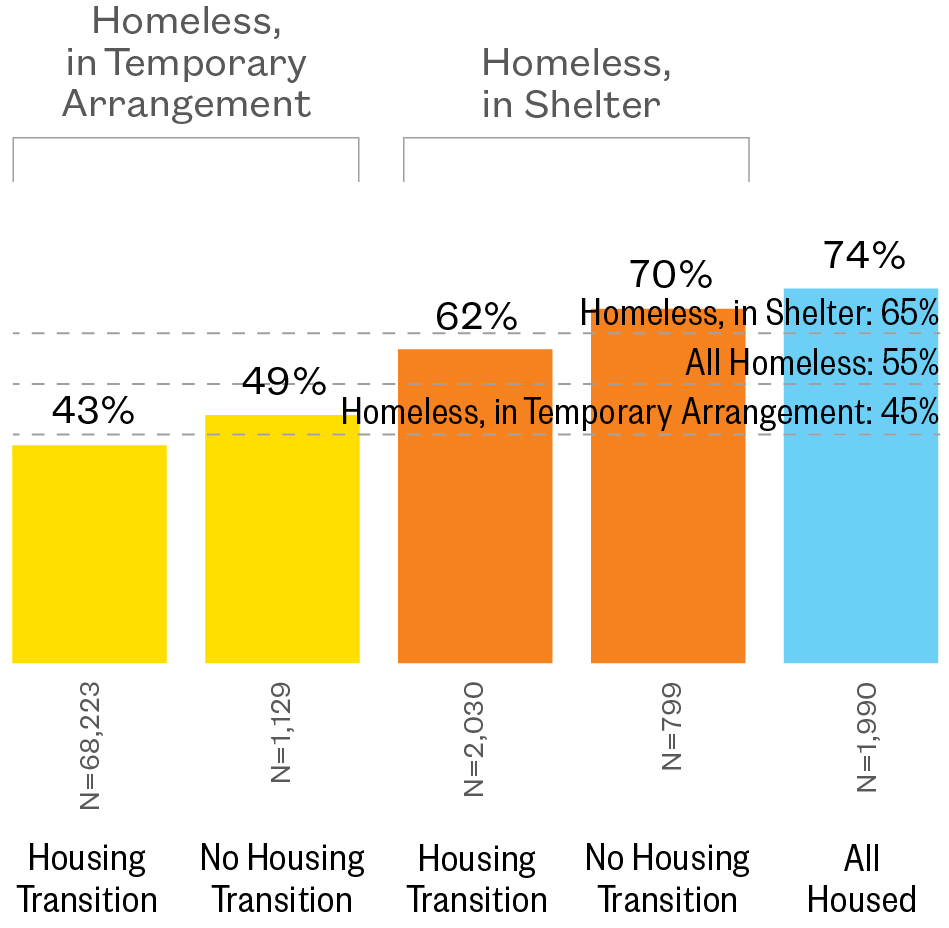

- Students living in shelter had the highest mid-year transfer rates of any housing status across all years from SY 2010–11 to SY 2015–16 (39% in SY 2010–11 and 33% in SY 2015–16). These students transferred mid-year at roughly four times the overall housed and citywide rates (33%, 7%, and 9%).

Every mid-year school transfer is estimated by the U.S. Department of Education to set a student back academically by up to six months.

Changes in Citywide Transfer Rates

Percent of Students Who Transferred Mid-Year, by Housing Status and Year

SY 2010–11 to SY 2015–16

Note: “All Homeless” includes all categories of homelessness.

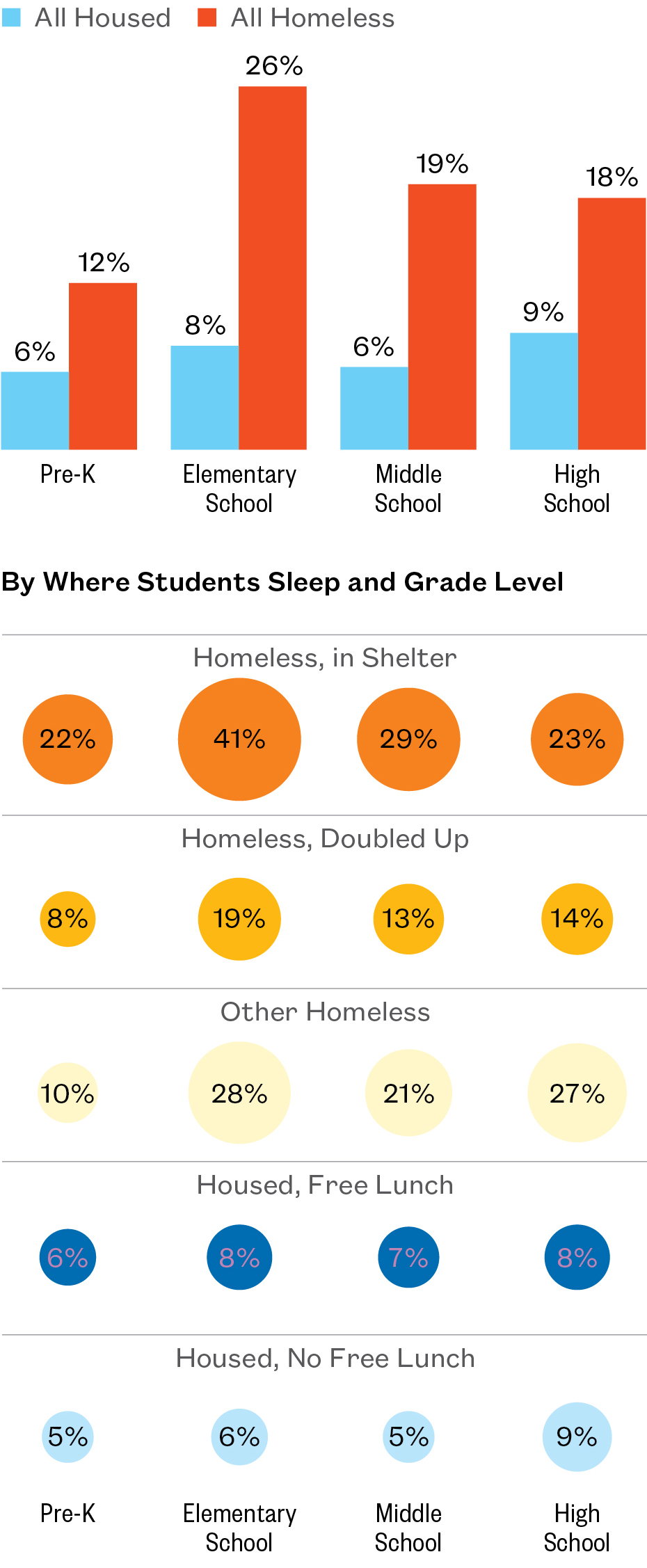

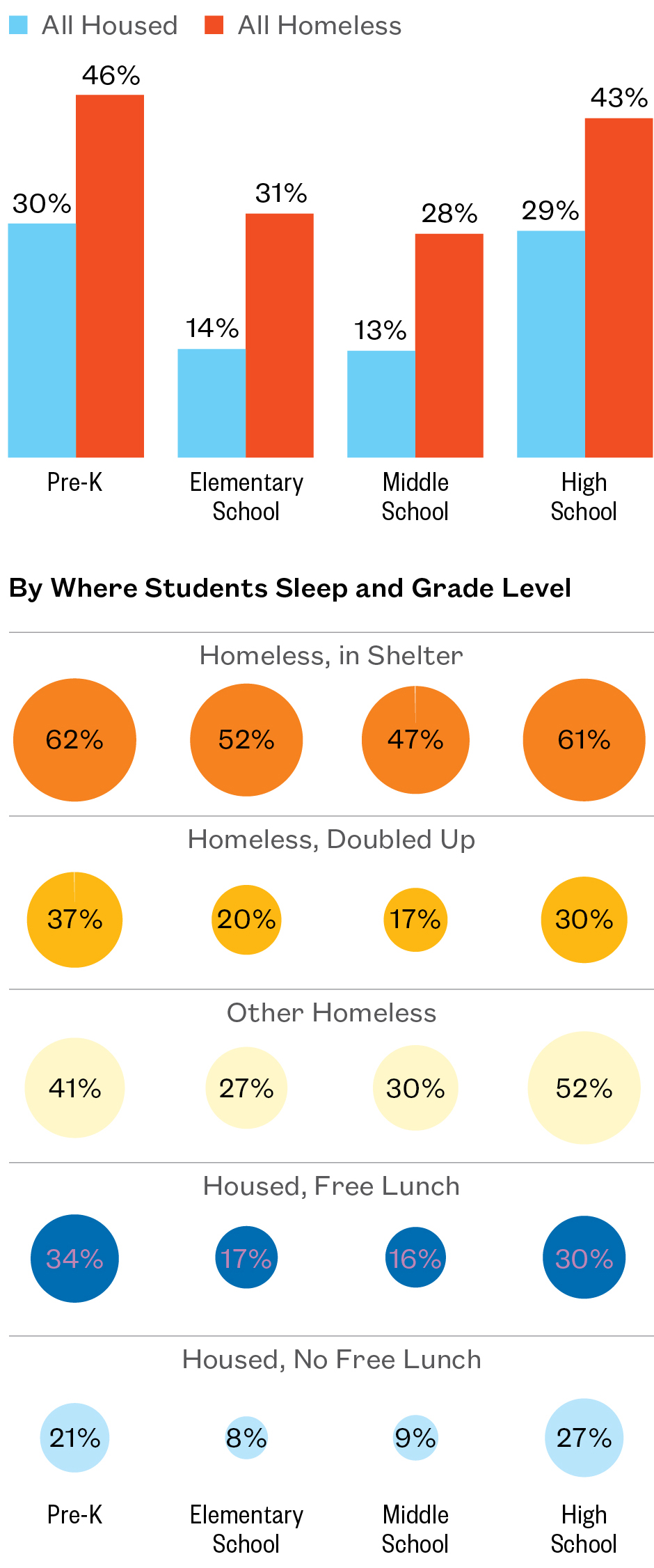

- Homeless elementary students had the highest mid-year transfer rate (26%) of any age group—roughly 50 percent higher than homeless students in middle and high school and over three times the rate of their housed elementary school peers. Among those living in shelter, this rate was even higher (41%).

- Across all grade levels, students living in shelter had the highest mid-year transfer rates followed by those in other homeless situations. While their rates were lower than sheltered and other homeless students, those living doubled up were still more likely to transfer mid-year than housed students (19% to 8% in elementary school).

- Students in other homeless settings who were not living doubled up or in shelter were also at a high risk of transferring schools mid-year (28% in elementary school).

Mid-Year Transfer Rates

Percent of Students Who Transferred

SY 2015–16

By Housing Status and Grade Level

Note: “Other Homeless” includes students who were awaiting foster care, paying for a hotel/motel outside of the shelter system, unsheltered, or living in another temporary and/or unsuitable housing situation. Students are categorized according to whether they experienced homelessness, lived in a shelter, or lived doubled up at any point during SY 2015-16.

Geographic Patterns of Mid-Year Transfers

School Instability Across Districts

Mid-Year Transfer Rate: Percent of Homeless Students Who Transferred Into or Within the District

SY 2015–16

Note: Transfer rate shows the percentage of homeless students who transferred into or within the district at some point during the school year. Data are by school district for SY 2015–16 and do not include schools in non-geographic districts.

Explore Districts at bit.ly/StudentAtlasApp.

- In every City school district, more than one in every ten homeless students transferred mid-year. This ranged from a low of 10% in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn to a high of one in three (34%) homeless students in Staten Island. (Districts 20 and 31)

- By borough, students living in shelter were most at risk for mid-year transfers in Staten Island and Queens (62% and 41%), while students living doubled up saw the highest rates in Staten Island and the Bronx (21% and 17%).

- Homeless students in Brooklyn’s East New York and Brownsville, Woodhaven in Queens, and Staten Island were at the greatest risk for school instability, with more than one in every four (26%–34%) homeless students transferring into the district mid-year. (Districts 19, 23, 27, and 31)

Many school districts face the dual challenges of high homelessness and mid-year transfers into schools, creating additional strain on limited school funding.

Mid-Year Transfer Rates

SY 2015–16

Note: Mid-year transfer rate shows the percentage of homeless students who transferred into or within the district at some point during SY 2015–16. Data by school district do not include schools in non-geographic districts, so borough and district total percentages may differ. Ns of fewer than 30 students were redacted.

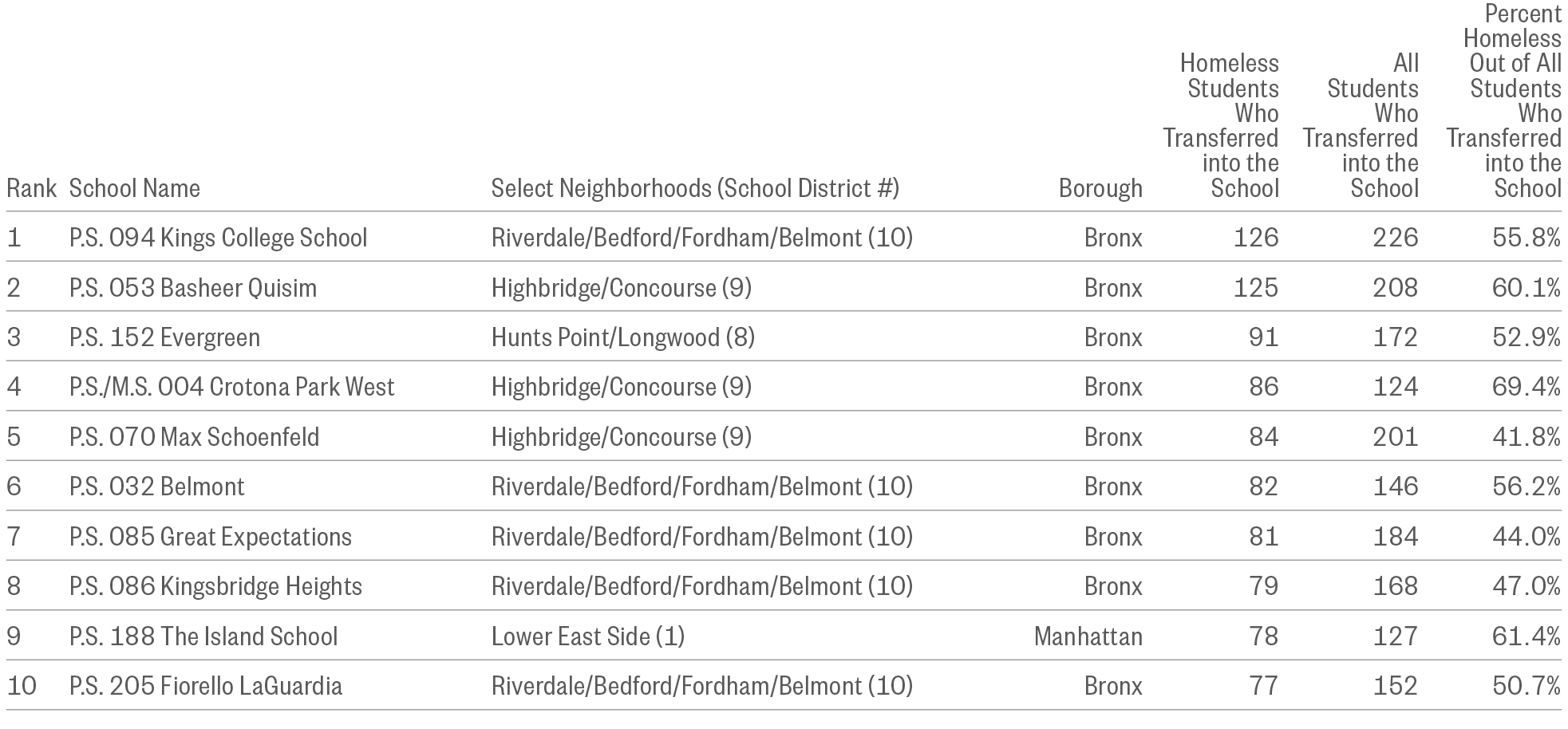

- Nine of the ten schools with the most homeless students transferring in mid-year were located in Hunts Point, Highbridge/Concourse, and Riverdale in the Bronx—areas of the city with the most family shelters. (Districts 8, 9, and 10)

- P.S. 094 Kings College School in Riverdale and P.S. 053 Basheer Quisim in Claremont Village had the most homeless students transferring into the school mid-year (126 and 125 students). (Districts 10 and 9, respectively) In these schools, homeless students represented more than half of all students who transferred into the school mid-year (56% and 60%).

Top 10 Schools for Homeless Student Transfers

Top 10 Schools for the Number of Homeless Students Who Transferred Into the School Mid-Year

SY 2015–16

See schools at bit.ly/MapNYCHomelessStudents

Top 10 Schools for Homeless Student Transfers

SY 2015–16

Note: Mid-year transfers represent homeless students who transferred into the school at some point during the school year. Schools with specialized service offerings were excluded from the ranking.

Note: Mid-year transfers represent homeless students who transferred into the school at some point during the school year. Schools with specialized service offerings were excluded from the ranking.

Homeless Students Transferring Out of School

Percent of Homeless Students Who Transferred Mid-Year Out of the School They Attended at the Start of the Year, by District

SY 2015–16

Note: Data are by school district for SY 2015–16 and do not include schools in non-geographic districts. Transfers include mid-year transfers only. Students who transferred more than once mid-year during SY 2015–16 were counted at their second-to-last school. School and district refer to the school attended at the start of the school year (on October 31st).

See schools at bit.ly/MapNYCHomelessStudents

- Overall, 22% of homeless students transferred out of their school mid-year in SY 2015–16.

- Homeless students attending school in Bedford-Stuyvesant and Brownsville in central Brooklyn were at the greatest risk of transferring out of the school they attended at the start of the year. Between 30% and 38% of homeless students who started the school year in those districts transferred out of their school mid-year. (Districts 16 and 23)

When students become homeless, exit homelessness to permanent housing, or undergo other housing transitions, their teacher and classmates are often the only stabilizing connections. Keeping students who are undergoing housing instability in the same school for the full year is critical.

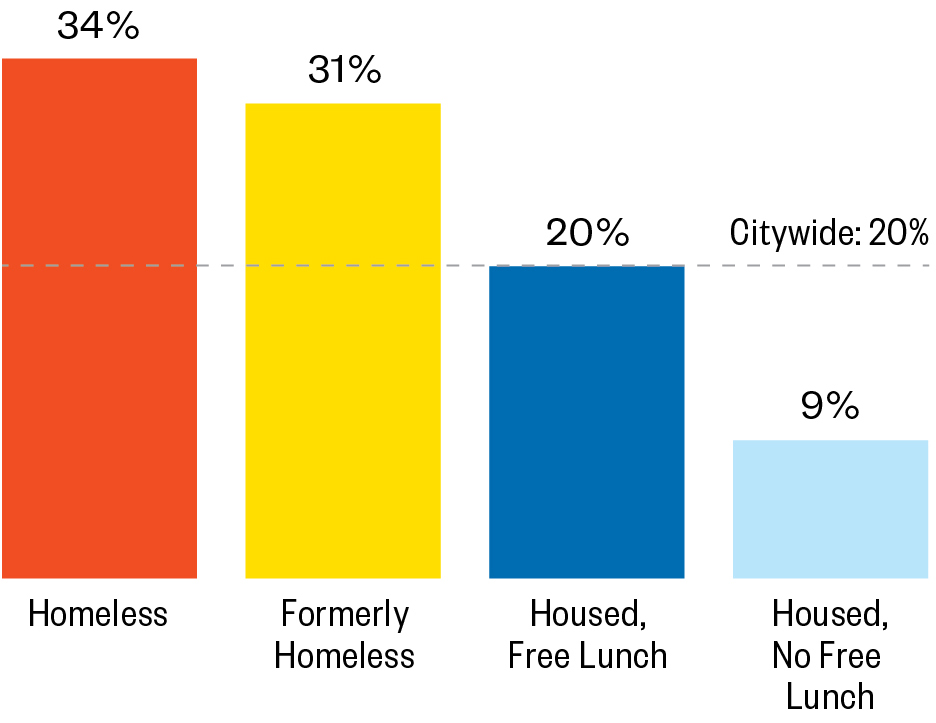

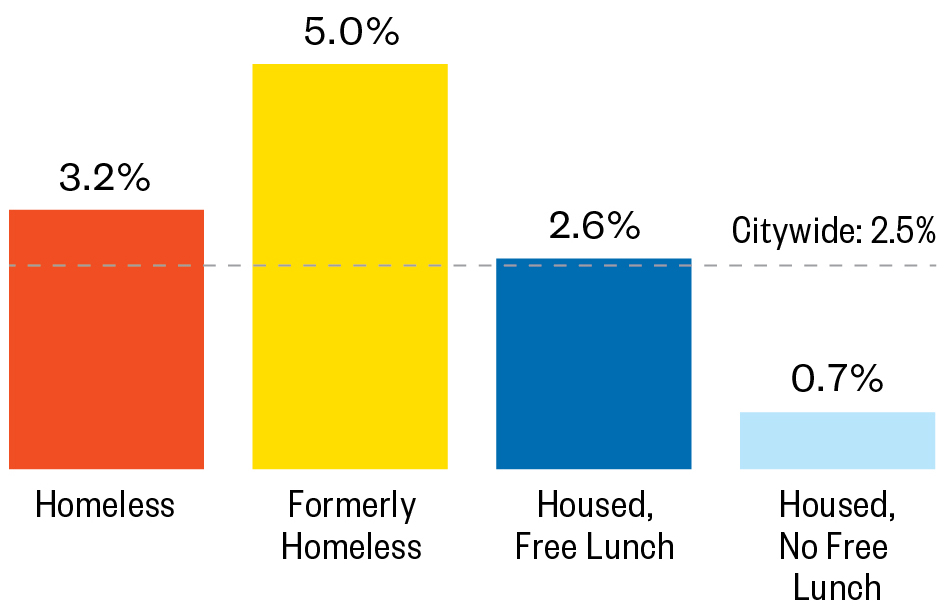

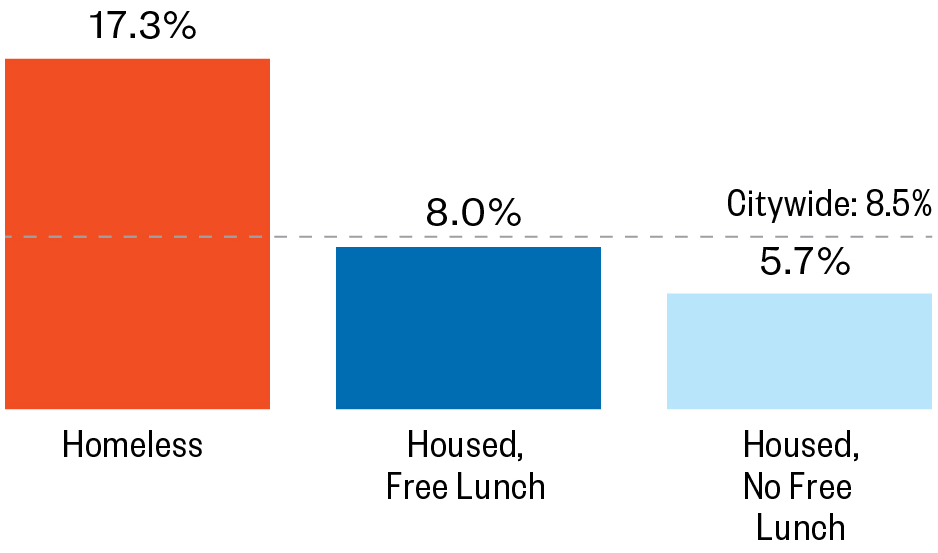

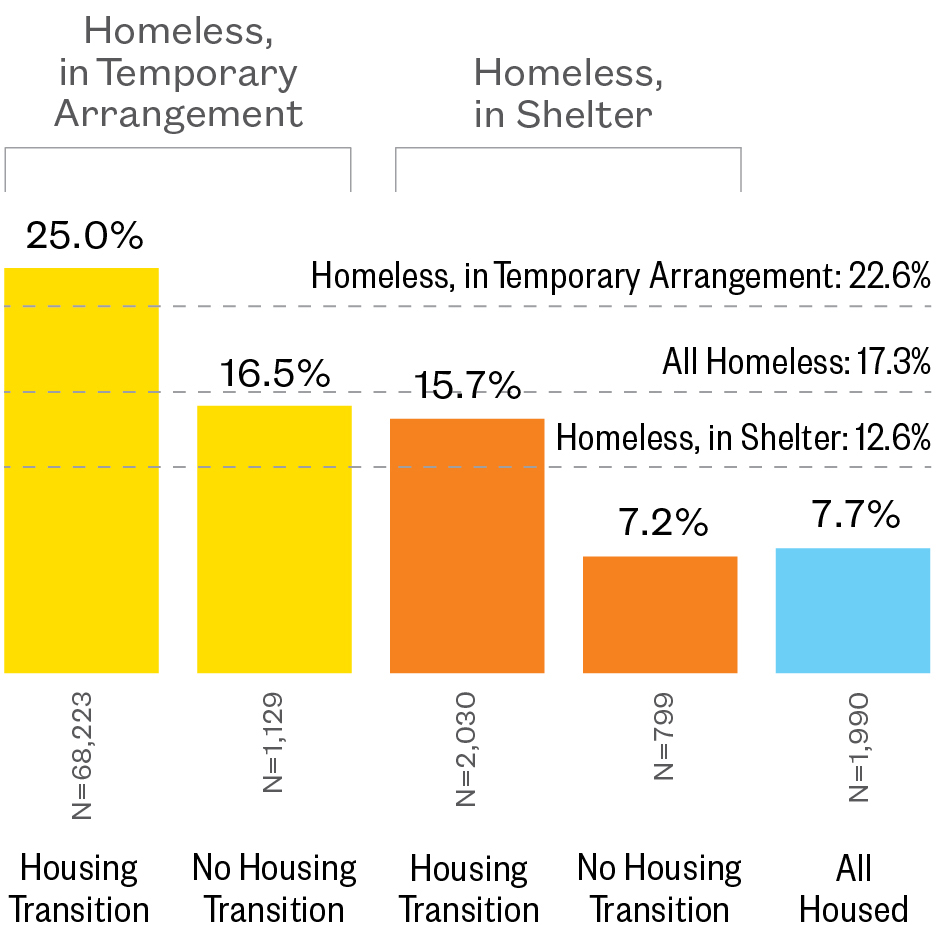

Empty Seats: Chronic Absenteeism

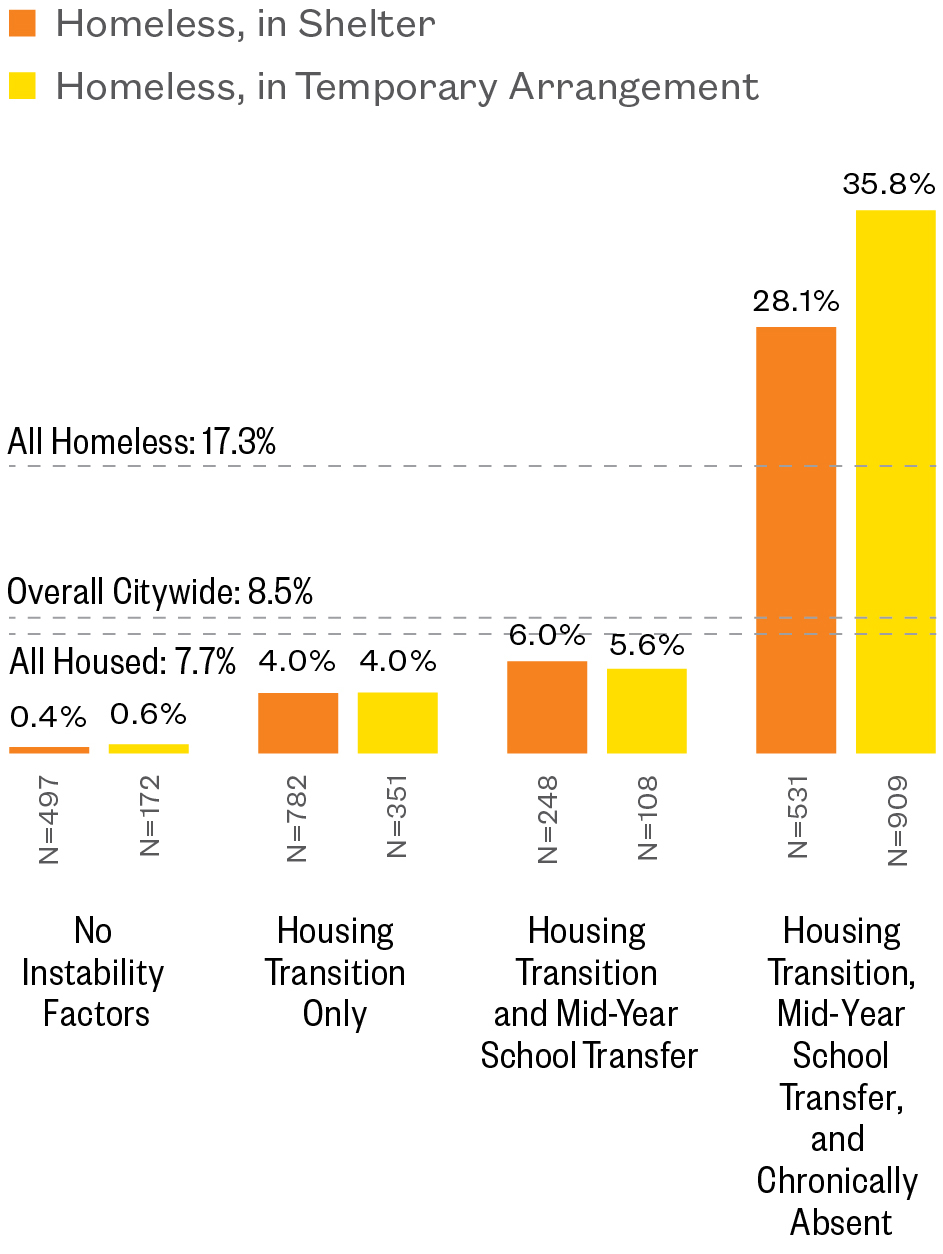

- On average, one-third of homeless students are chronically absent, missing 20 or more school days in one year— the equivalent of one month of school. This rate is 50 percent higher than the citywide average of low-income students who are housed (34% and 20%).

- One-third of homeless students (34%) were chronically absent, close to four times the rate of housed students who were not low income (9%).

- Students who had a history of homelessness but were housed in SY 2015–16 (formerly homeless) were still facing instability at school. Almost a third (31%) were chronically absent, just three points lower than students who experienced homelessness during SY 2015–16 (31% and 34%).

Formerly homeless students represent a distinct group of children who are still experiencing lingering destabilizing effects on their educations. This highlights the need for ongoing academic and social supports for students even after students are no longer homeless.

Chronic Absenteeism Rate

Percent of Students Missing 20 or More School Days in One Year

SY 2015–16

Note: “Formerly Homeless” includes students who were housed during SY 2015–16 but were homeless at any point during SY 2010–11, SY 2011–12, SY 2012–13, SY 2013–14, and/or SY 2014–15.

- Formerly homeless students experienced almost the same risk of absenteeism as their currently homeless classmates, highlighting the lingering destabilizing effects of homelessness on students’ educations.

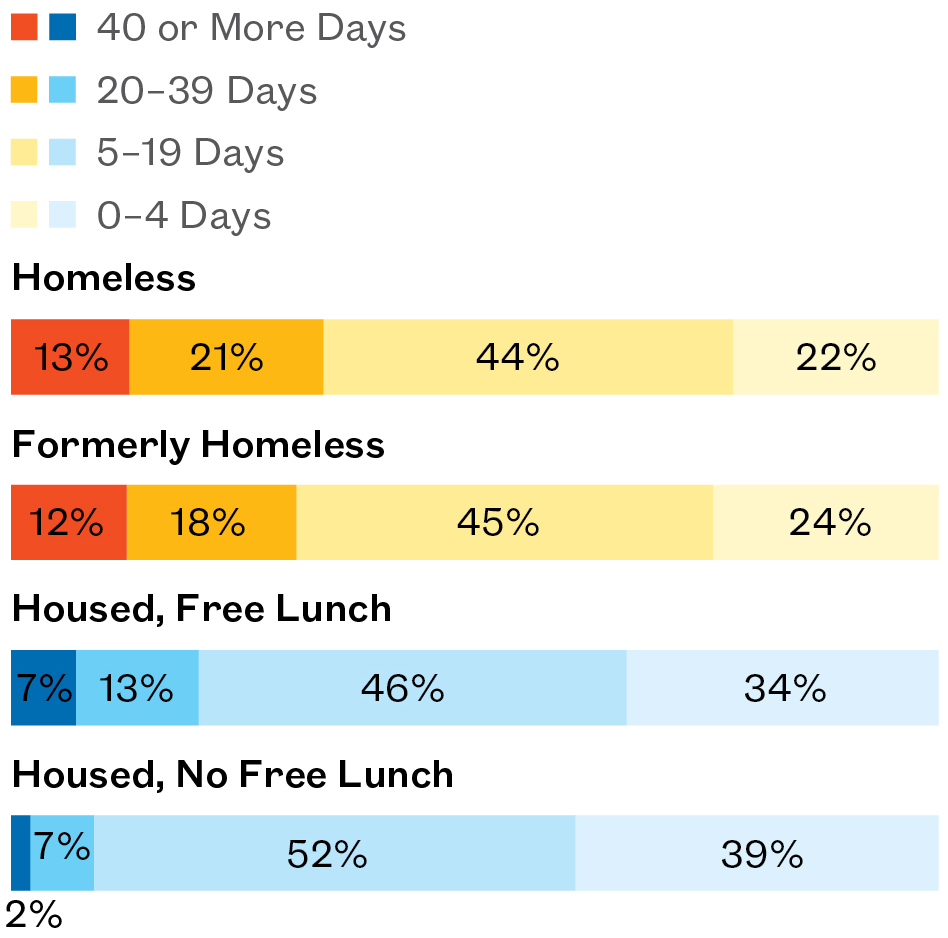

- Roughly one-third of homeless and formerly homeless students missed 20 or more days of school in SY 2015–16, making them chronically absent (34% and 31%).

- One in eight homeless and formerly homeless students missed 40 or more school days in SY 2015–16—roughly 20% of the school year.

Number of Days Absent, by Housing Status

SY 2015–16

Note: “Formerly Homeless” includes students who were housed during SY 2015–16 but were homeless at any point during SY 2010–11, SY 2011–12, SY 2012–13, SY 2013–14, and/or SY 2014–15. Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding.

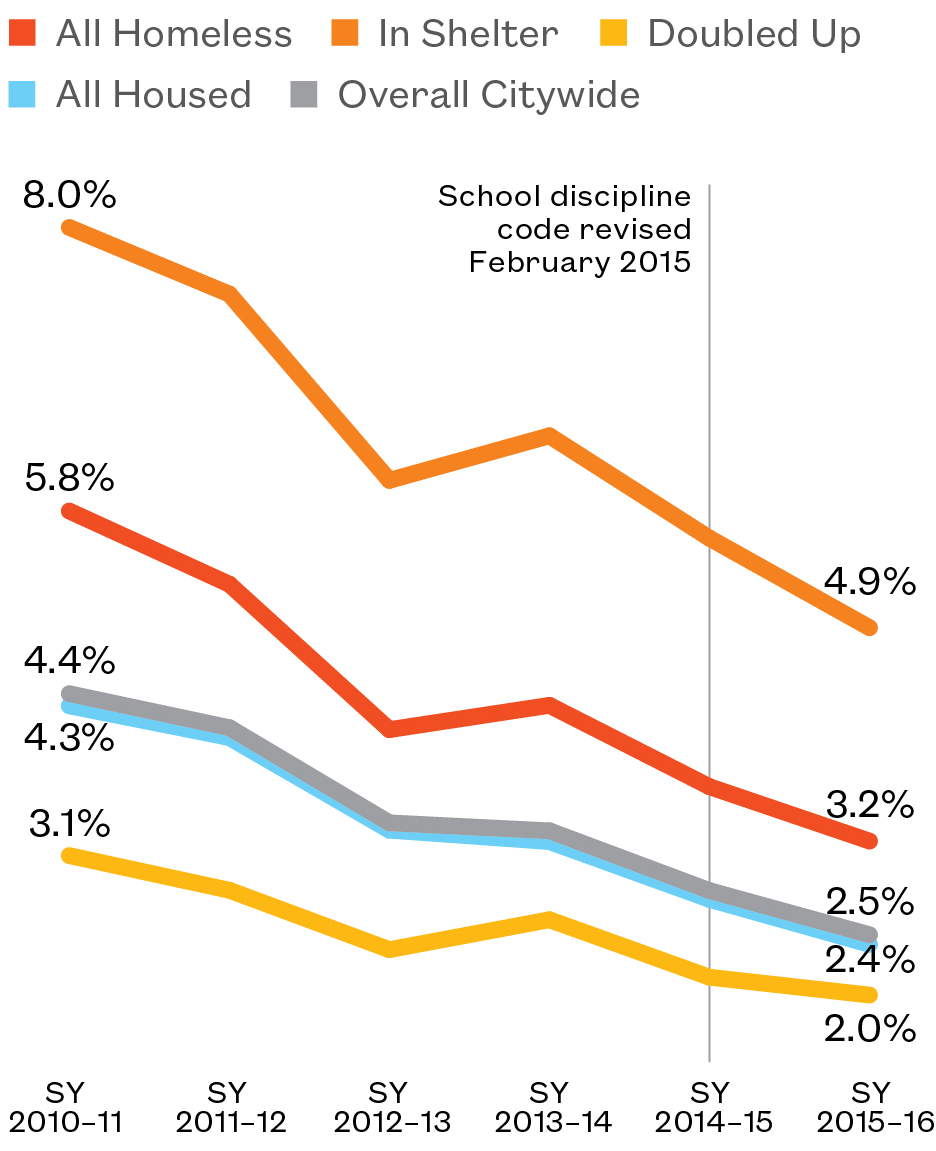

- As New York City has sought to improve attendance for students citywide, homeless students overall saw a 20 percent rate decline in their chronic absenteeism rate in six years—from 41% to 34% (SY 2010–11 to SY 2015–16).

- However, the declines in the overall citywide and homeless student chronic absenteeism rates exaggerate the degree of improvement. When rates are broken out by type of housing setting, both sheltered and doubled-up students saw small declines in their chronic absenteeism rates compared to housed students. Much of the overall improvement among homeless students was due to the increase in the number of doubled-up students in the city.

Examining trends over time by the type of homelessness experienced is critical to assessing the impacts of policies and programs.

Changes in Citywide Chronic Absenteeism Rates

Percent of Students Chronically Absent, by Housing Status and Year

SY 2010–11 to SY 2015–16

Note: New York City has been making strong commitments to improve attendance among students. Most recently, the de Blasio administration announced its expansion of the community schools initiative in June 2014. The first phase was planned to target 45 Attendance Improvement and Dropout Prevention (AIDP) schools. In the following years, more than 100 schools were served by the Community Schools model. “All Homeless” includes all categories of homelessness.

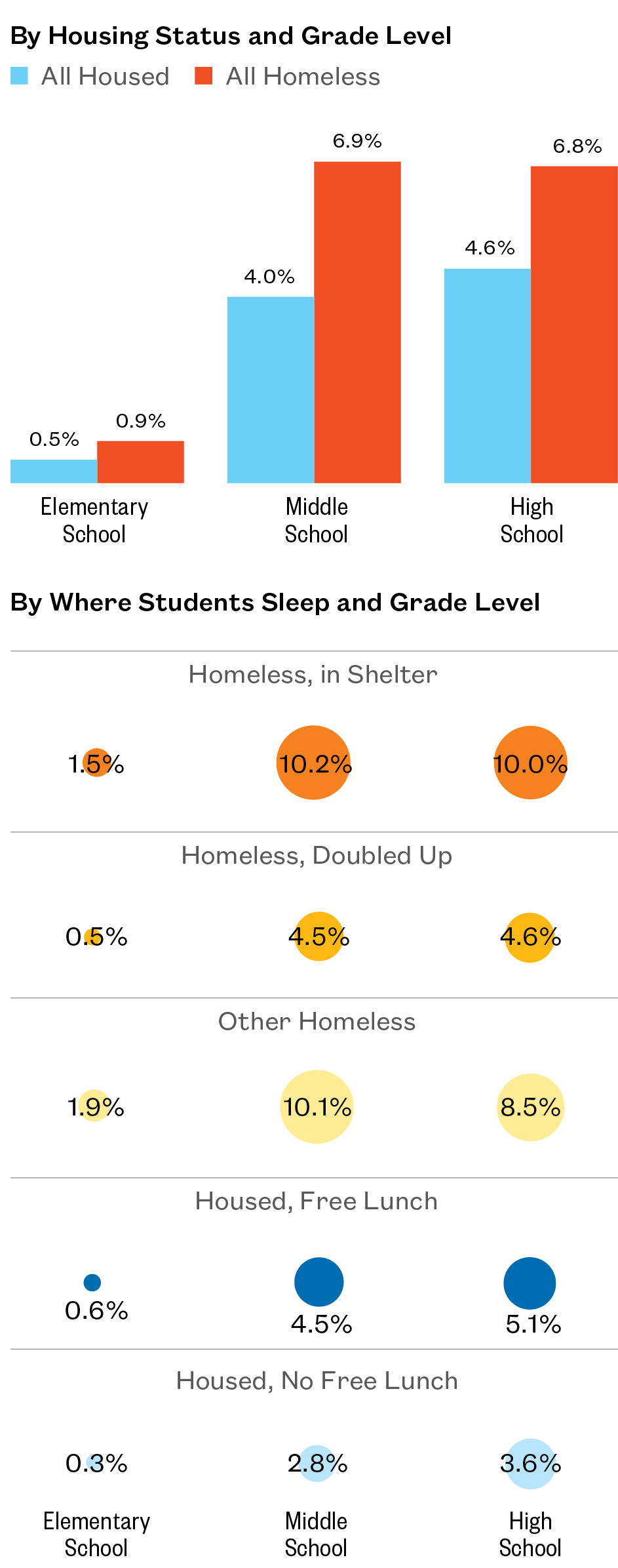

- Homeless students of all ages were at a greater risk for chronic absenteeism than their housed peers. The gap was greatest in elementary school, when 31% of homeless students missed 20 or more school days—more than twice the rate of housed students (14%).

- Students living in homeless and housed settings alike were at a heightened risk for absenteeism in both pre-K and high school, with homeless students in those grades chronically absent at 50 percent higher rates than their peers in elementary and middle school.

- Across grade levels, homeless students living in shelter had higher chronic absenteeism rates than their homeless peers living doubled up.

Chronic Absenteeism Rates

Percent of Students Chronically Absent

SY 2015–16

By Housing Status and Grade Level

Note: “Other Homeless” includes students who were awaiting foster care, paying for a hotel/motel outside of the shelter system, or living in another temporary and/or unsuitable housing situation.

Geographic Patterns of Absenteeism

Chronic Absenteeism Among Homeless Students

SY 2015–16

Note: Data are by school district for SY 2015–16 and do not include schools in non-geographic districts.

Explore Districts at bit.ly/StudentAtlasApp.

- On average, 34% of homeless students were chronically absent. This ranged from a low of 14% in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn to a high of 44% of homeless students in nearby Brownsville. (Districts 20 and 23)

- By borough, chronic absenteeism rates were highest for students living in shelter in Staten Island and in Queens (66% and 54%), while students living doubled up were most at risk for chronic absenteeism in Staten Island and the Bronx (25% and 24%).

- Across all school districts, homeless students living in shelter had the highest rates of chronic absenteeism when compared to all other housing and income groups.

Chronic Absenteeism Rate

SY 2015–16

Note: Mid-year transfer rate shows the percentage of homeless students who transferred into or within the district at some point during SY 2015–16. Data by school district do not include schools in non-geographic districts, so borough and district total percentages may differ. Ns of fewer than 30 students were redacted.

- Schools with the highest rates of absenteeism for homeless students were likely to be schools where housed students struggled as well. Close to 90% of homeless students were chronically absent at two schools in Clinton Hill, while over 80% of their housed classmates were chronically absent. (District 13)

The New York City Department of Education is supporting schools with high absenteeism by hiring additional attendance teachers and bolstering communication between shelters and schools. Continuing to develop targeted supports that combat absenteeism for both homeless and housed students is critical.

Top 10 Schools for Homeless Student Chronic Absenteeism

SY 2015–16

See schools at bit.ly/MapNYCHomelessStudents

Top 10 Schools for Homeless Student Chronic Absenteeism

SY 2015–16

Note: Schools with specialized service offerings were excluded from the ranking.

Note: Schools with specialized service offerings were excluded from the ranking.

Download Section 2 PDF

To explore homelessness in New York City schools, try our interactive map.

To learn more about the educational outcomes of homeless New York city students, try our Student Atlas app.

Return to top.

Section 3

Additional Support Needs of Homeless Students: Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) and English Language Learning (ELL) Services

“You can really see from the younger grades the impact [missing a lot of school] can have. When a student is in 4th or 5th grade, you see how they are in a totally different track than they would have been if they had stable housing and had access to all the resources that they need.”

—Social Work Director, Partnership with Children,working in Brooklyn public schools

“For most of the time [living in shelter], I would have to come early from school to be able to help [my Spanish-speaking grandmother/guardian] attend her appointments with the case worker or housing specialist. It definitely impacted my school but there was nothing I could do about it. I had to just handle it.”

—High school graduate, former participant in NYC Department of Education Students in Temporary Housing (STH) Unit supportive program

Over 55,000 students with additional educational needs experienced homelessness between SY 2010–11 and SY 2015–16, including students who were English Language Learners and those with special education support needs. However, homeless students are often unable to access the additional supports that they need, making it harder to keep pace with their age-and grade-level peers. Addressing the disparity in the receipt of supportive educational services will require multifaceted solutions, from programs that strengthen school engagement and stability to a focus on early screening and intervention. Ensuring that identification services are taking into account the individual needs of homeless students is key to ensuring that all students have an equal chance at receiving educational supports.

What’s New?

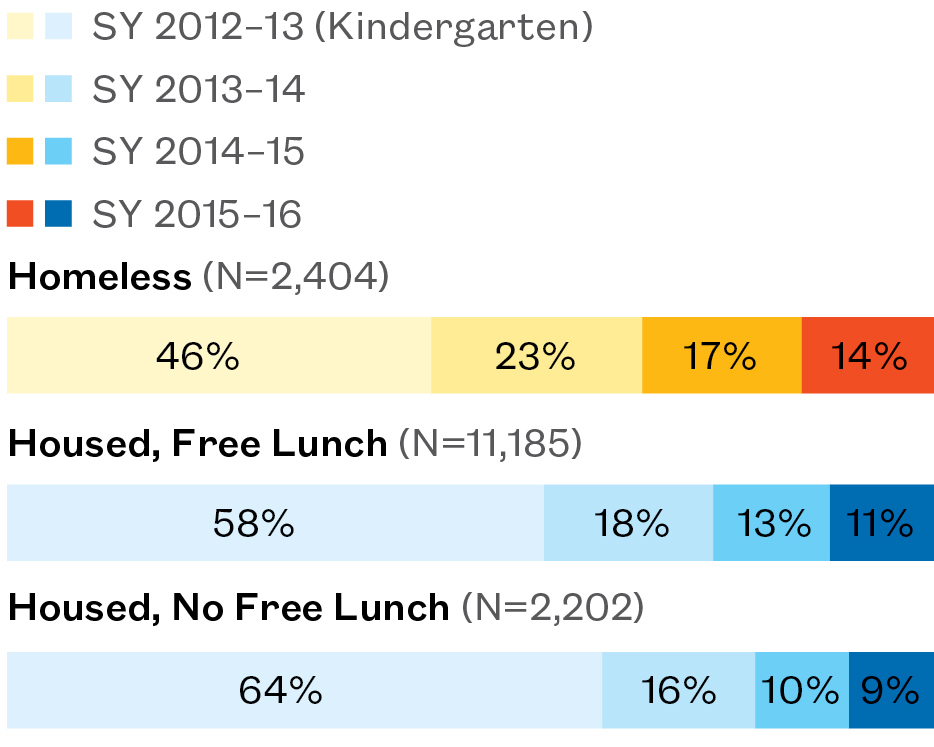

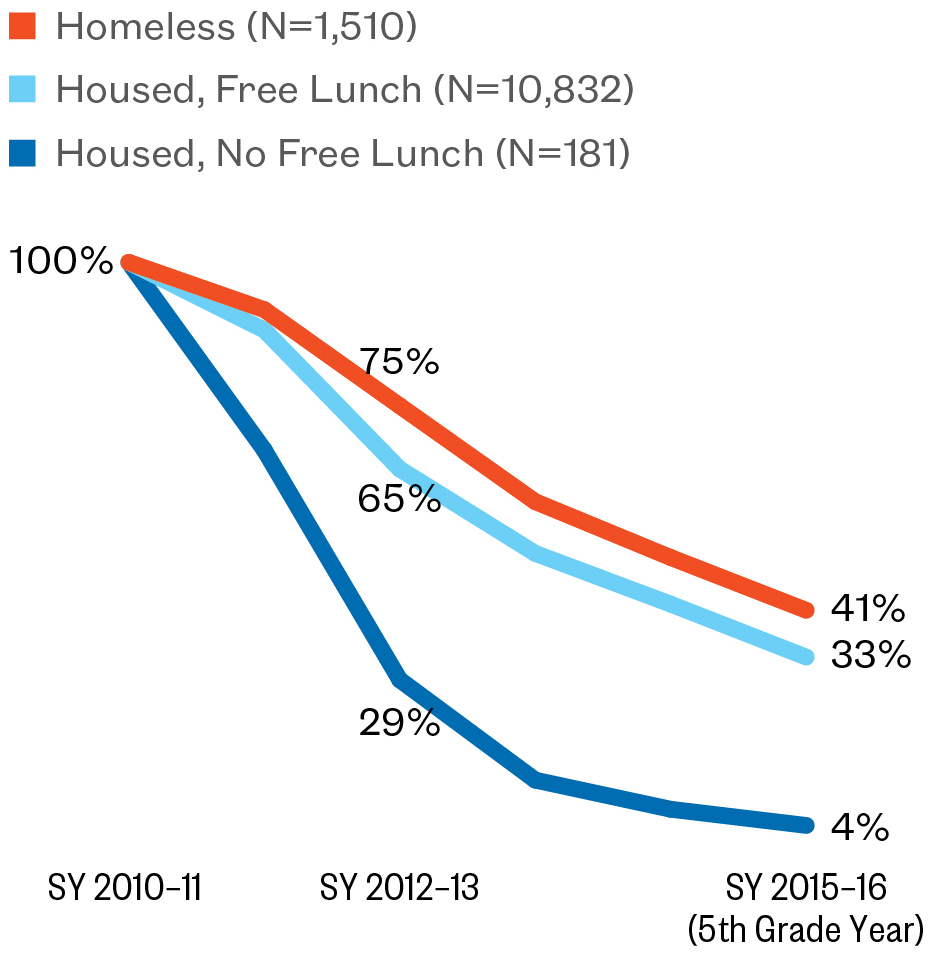

Not only were homeless students more likely to require English Language Learning (ELL) services when compared to their housed classmates, but they were also more likely to be designated as ELL for longer than their low-income and non-low-income housed peers. More than 40% of homeless ELL students still required ELL services after six years compared to one-third of low-income housed students and only 4% of non-low-income housed students.

Policy Considerations

When students are identified as needing ELL or IEP services, their school stability becomes paramount. Children who are frequently absent or who transfer mid-year struggle to receive the same consistent support for their special education or English language learning needs, and face additional challenges catching up to their classmates. Unless needed school stability and attendance supports are provided, schools’ ability to meet homeless students’ additional support needs will be in jeopardy.

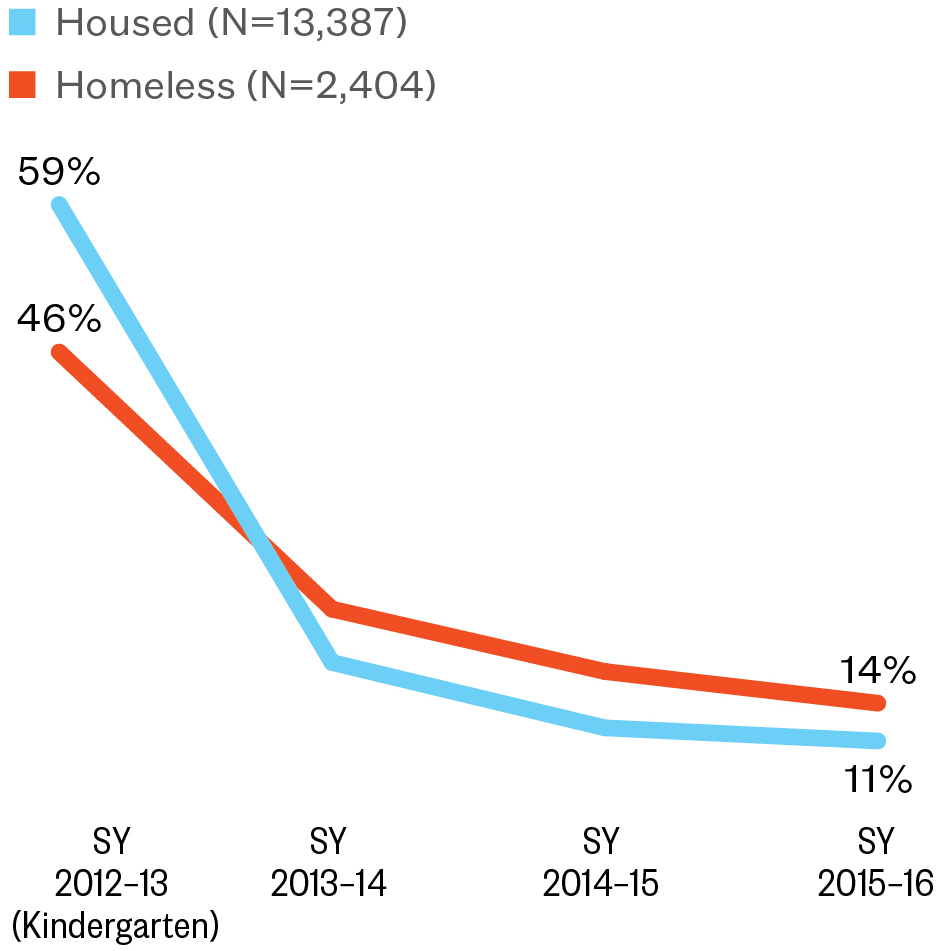

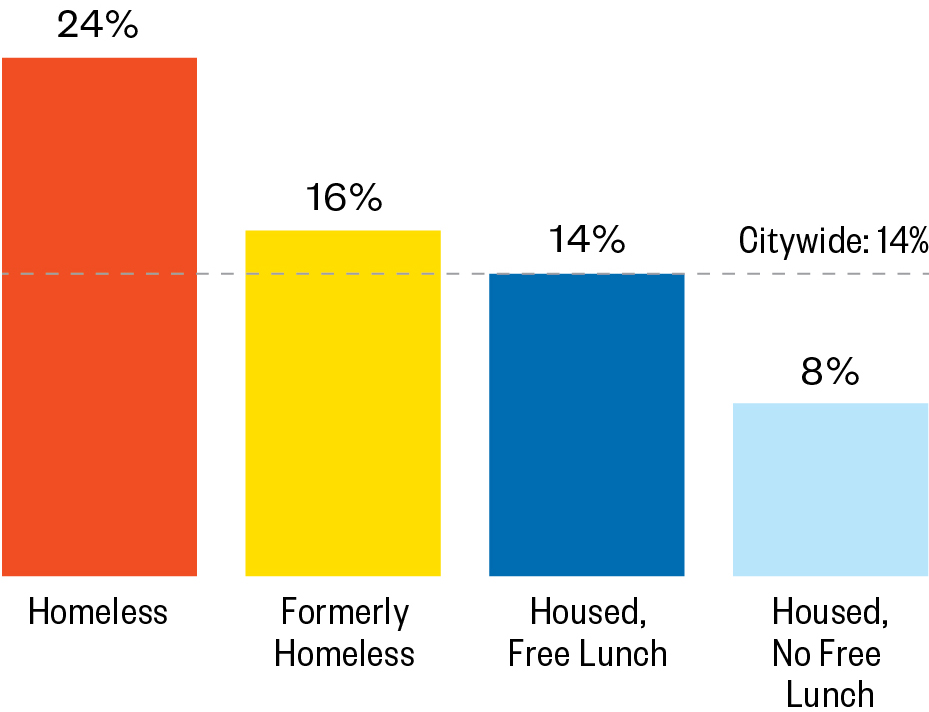

Overlooked: Who Receives Late IEPs?

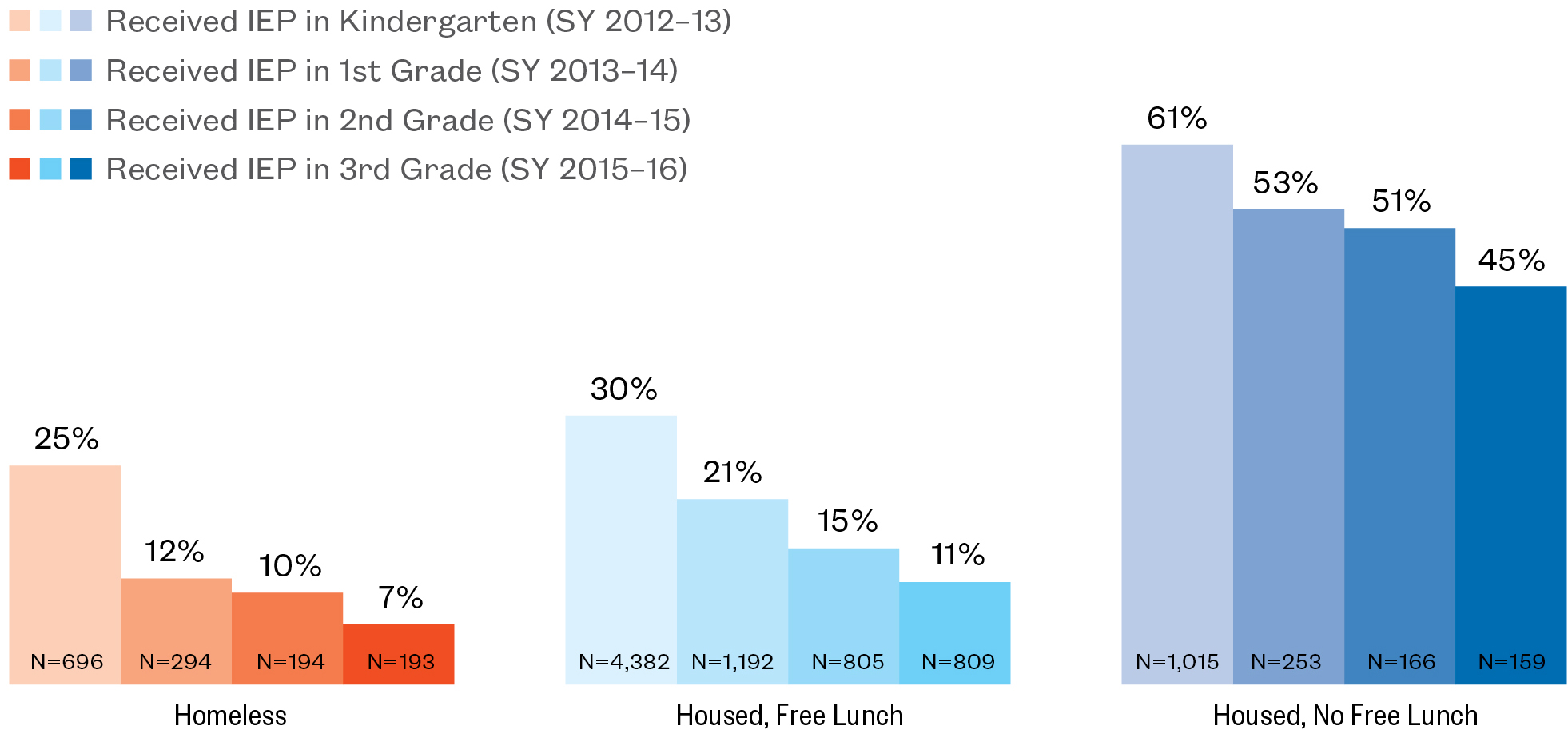

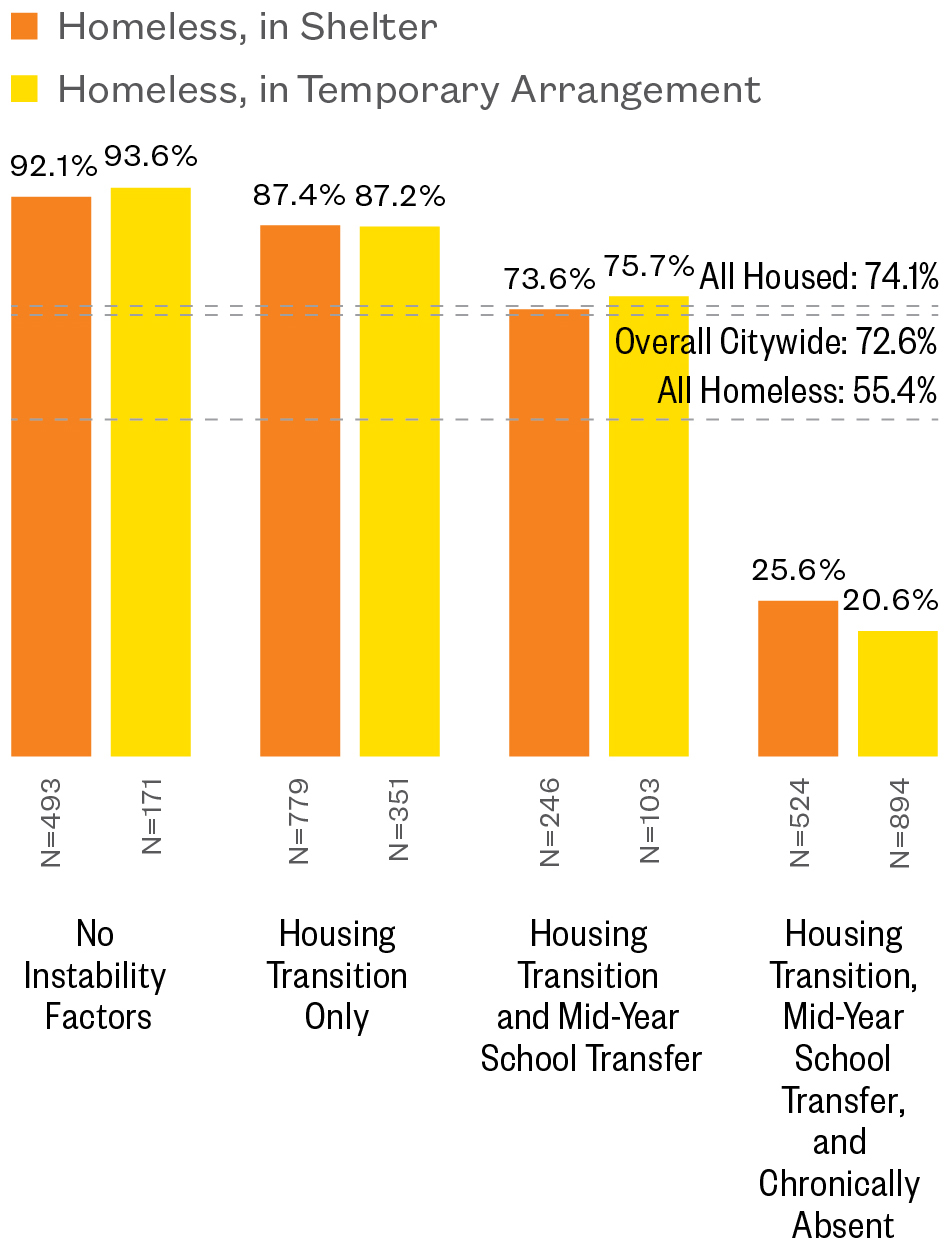

- Homeless students were more likely than their housed peers to have their IEP needs identified late. Less than half (46%) of homeless students with IEPs were identified by the end of Kindergarten compared to 59% of housed students.

- The disparity in late identification of special education needs exists beyond poverty. Less than half (46%) of homeless students who had been homeless at some point received their IEP by the end of Kindergarten, compared to 58% among low-income housed students and almost two-thirds (64%) of non-low-income housed students.

- One in seven (14%) students who had ever been homeless received their IEP in SY 2015–16—their third-grade year, compared to 11% of low-income housed students and 9% for housed students who were not low income.

The Individualized Education Plan (IEP) outlines the special education services a student will receive to support their learning. Districts are legally required to identify and evaluate all children facing challenges within one of 13 disability categories such as speech or language impairment and learning disabilities.

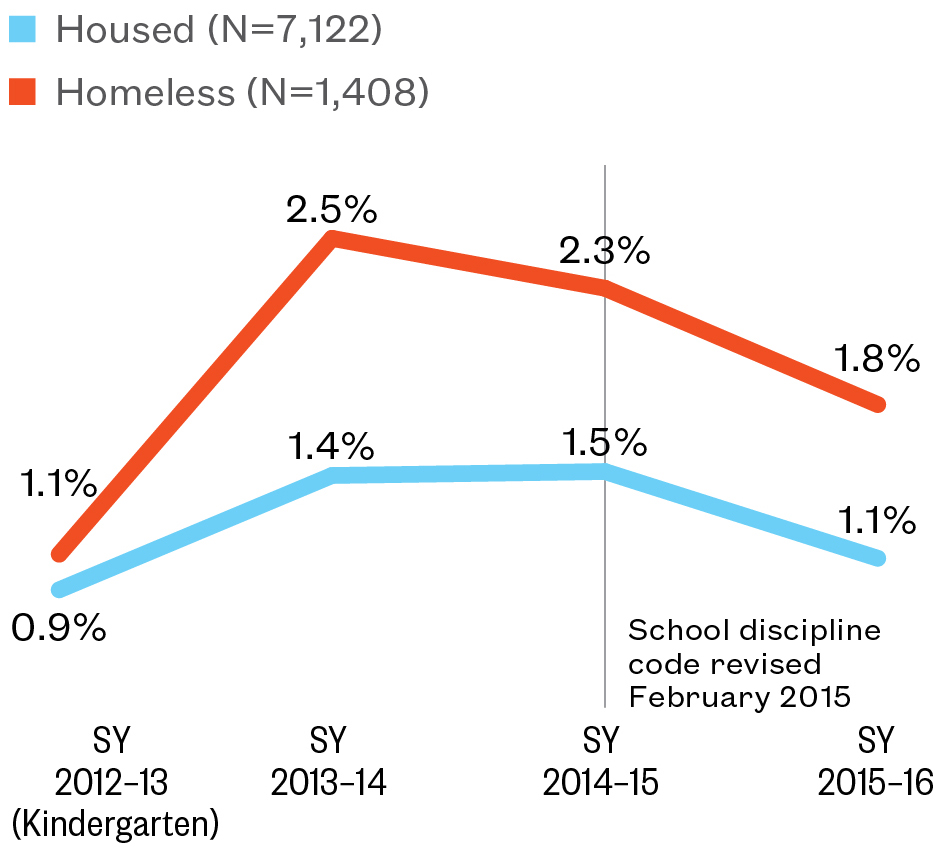

Year Received an IEP

SY 2012–13 to SY 2015–16

Note: Housing status is over four years. “Housed” indicates that the student never experienced homelessness. “Homeless” indicates that the student was homeless at some point in the four-year period. These data represent a cohort of students who entered Kindergarten in SY 2012–13 and received an IEP at some point during the next four years.

Year Received an IEP, by Housing Status

SY 2012–13 to SY 2015–16

Note: Students are categorized according to whether they experienced homelessness or received free lunch at any point during the four-year period. These data represent a cohort of students who entered Kindergarten in SY 2012–13 and received an IEP at some point during the next four years. Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding.

- Amidst citywide policy changes bringing special education students back into general education classrooms and their neighborhood schools, City public schools have succeeded in identifying students earlier for IEPs. Among special education students citywide, those in the SY 2015–16 cohort were less likely to be identified late (after Kindergarten) than students in the SY 2013–14 cohort (43% to 46% overall).

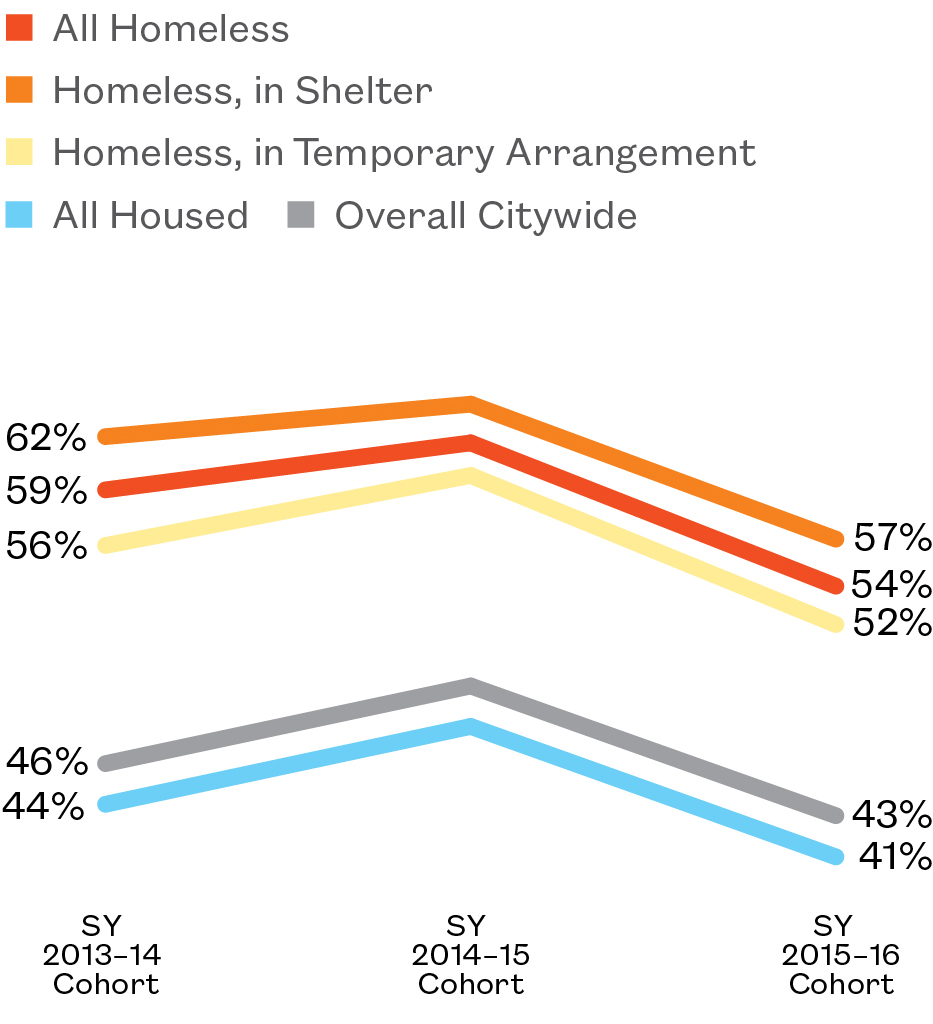

- Homeless students also saw a decline in the percentage receiving their IEP late (after Kindergarten) from 59% in the SY 2013–14 cohort to 54% in the SY 2015–16 cohort. Still, these rates of late identification over time were higher than housed students, placing young homeless children at greater risk for having unidentified special education needs.

- The rates of late IEP identification for students who had been in shelter were higher than homeless students who lived in other non-shelter temporary arrangements (57% to 52% in the SY 2015–16 cohort)

Going without needed supports for the first three years of a child’s education makes it harder to keep pace with their age- and grade-level peers, especially when the child is also undergoing other challenges associated with housing instability. How can City shelters and schools further support young students and parents to navigate the IEP process?

Changes in Citywide Late IEP Rates

Percent of Students with Special Education Needs Who Received IEP Late (After Kindergarten), by Housing Status and Year

SY 2010–11 to SY 2015–16

Note: Cohorts represent groups of students who attended New York City Public Schools for four years ending in the cohort year (SY 2013–14, SY 2014–15, or SY 2015–16) and received an IEP at some point during the four years. Students are categorized according to whether they experienced homelessness or lived in a shelter at any point during the four-year cohort periods.

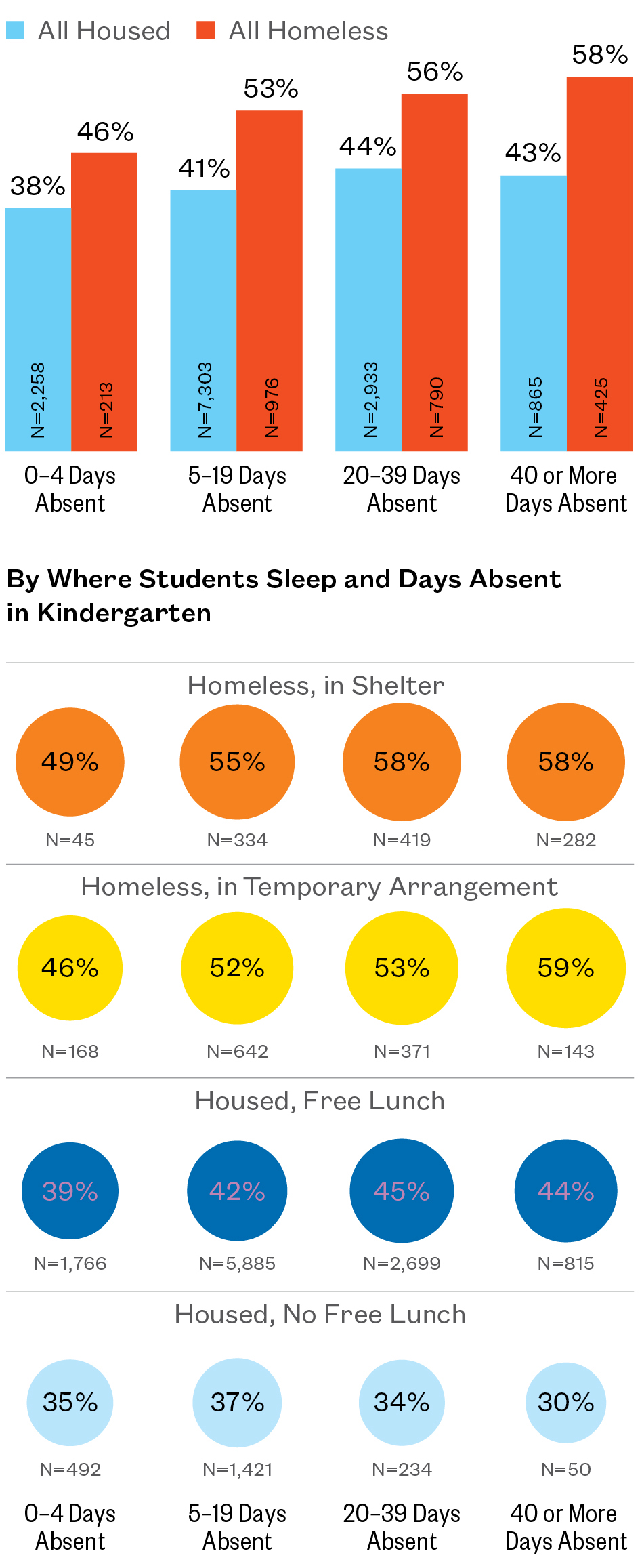

- School absences increase the risk of late IEP identification. This effect is even more pronounced for homeless students: those with 40 or more absences in one school year had a 12-point higher rate of late IEP identification compared to their homeless peers with only 0–4 absences, while housed students saw a roughly five-point gap driven by absences.

- Among students who missed just four or fewer school days in Kindergarten, less than half of homeless students received their IEP late. This was just eight points higher than the rate for housed students (46% to 38%).

Absenteeism places students at risk of not only falling behind academically, but also slipping through the cracks when it comes to identification of additional support needs.

Late IEP Rates by Absenteeism

Percent of Students with Special Education Needs Who Received IEP Late (After Kindergarten)

SY 2012–13 to SY 2015–16

By Housing Status and Days Absent in Kindergarten

Note: Absenteeism reflects days absent in Kindergarten. These data represent a cohort of students who entered Kindergarten in SY 2012–13 and received an IEP at some point during the next four years. Students are categorized according to whether they experienced homelessness, lived in a shelter, or received free lunch at any point during the four-year period.

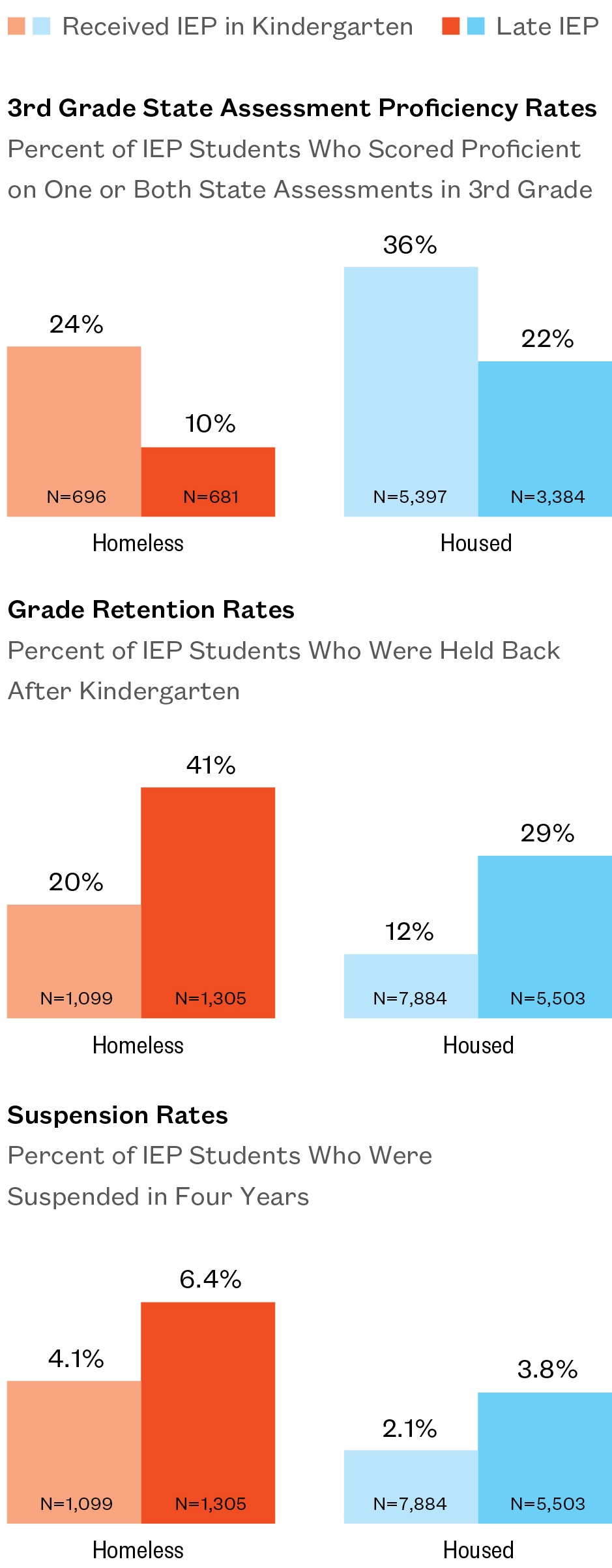

Early Identification Matters

- One-quarter (24%) of homeless students who received their IEP by the end of Kindergarten scored proficient on their 3rd grade State assessments. Meanwhile, only one in 10 homeless students with late IEPs were proficient. This gap was similar for housed students, although housed proficiency rates were higher.

- Forty-one percent (41%) of homeless students with late IEPs were held back at some point. Homeless peers with early IEPs saw half that rate, however—20% repeated a grade. While early identification helped, grade retention was higher for homeless students than their housed peers (20% to 12%).

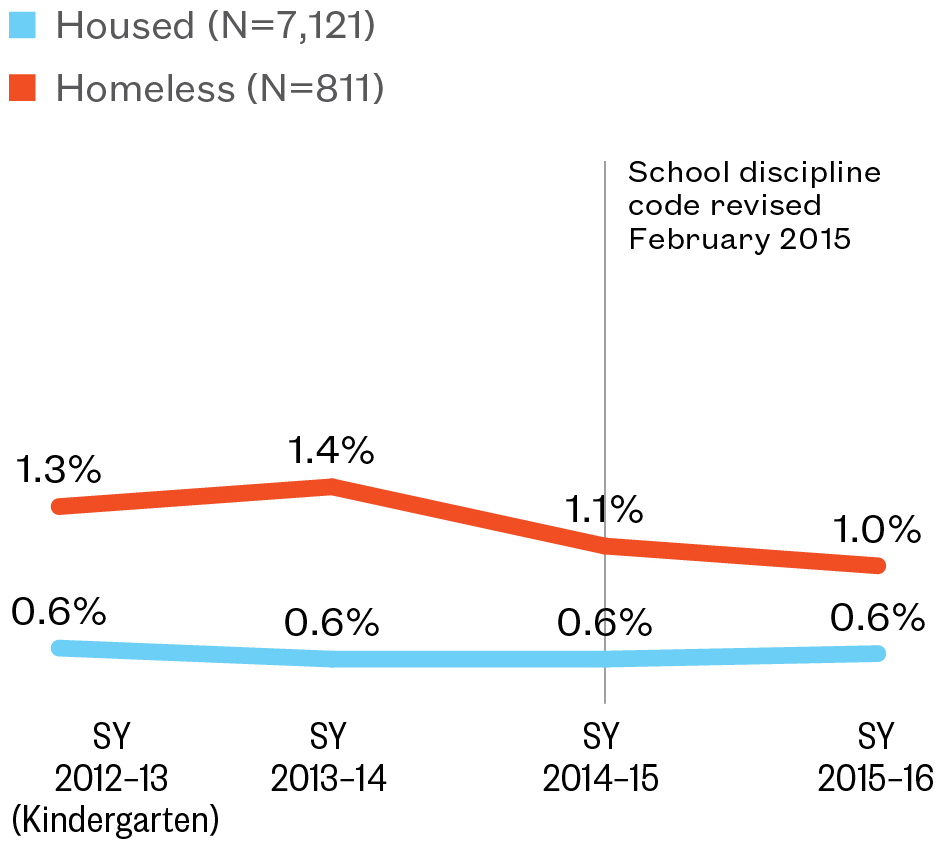

- Homeless special education students were at a greater risk of suspension if they received their IEP late (after Kindergarten). Four percent of homeless students who received their IEP in Kindergarten were suspended at some point, while six percent of those who went unidentified for special education services were suspended. A similar pattern existed among housed students, though homeless students had roughly twice the suspension rates of housed students.

Ensuring that homeless students with additional support needs are connected with services at an early age can increase educational success.

Educational Outcomes by Late IEPs

SY 2012–13 to SY 2015–16

Note: These data represent a cohort of students who entered Kindergarten in SY 2012–13 and received an IEP at some point during the next four years. IEP students who were held back or followed a nontraditional path for another reason were excluded from the 3rd Grade State Assessment Proficiency Rates calculation. This publication uses the words “retention” and “held back” interchangeably. Housing status is over four years. “Housed” indicates that the student never experienced homelessness. “Homeless” indicates that the student was homeless at some point in the four-year period.

3rd Grade State Assessment Proficiency Rates, by Year Received an IEP

Percent of IEP Students Who Scored Proficient on One or Both State Assessments in 3rd Grade

SY 2012–13 to SY 2015–16

Suspension Rate Among Students Who Received IEPs by the End of Kindergarten

SY 2012–13 to SY 2015–16

Suspension Rate Among Students Who Received IEPs Late (After Kindergarten)

SY 2012–13 to SY 2015–16

Note: State assessments include English Language Arts and math assessments. IEP group students who were held back or followed a nontraditional path for another reason were excluded from the State Assessment chart. Housing status is over four years. Students are categorized according to whether they experienced homelessness or received free lunch at any point during the four-year period. These data represent a cohort of students who entered Kindergarten in SY 2012–13 and received an IEP at some point during the next four years. School discipline code reforms in February 2015 include approval required for principals to give out-of-school suspensions, and the reasons for out-of-school suspensions were restricted.

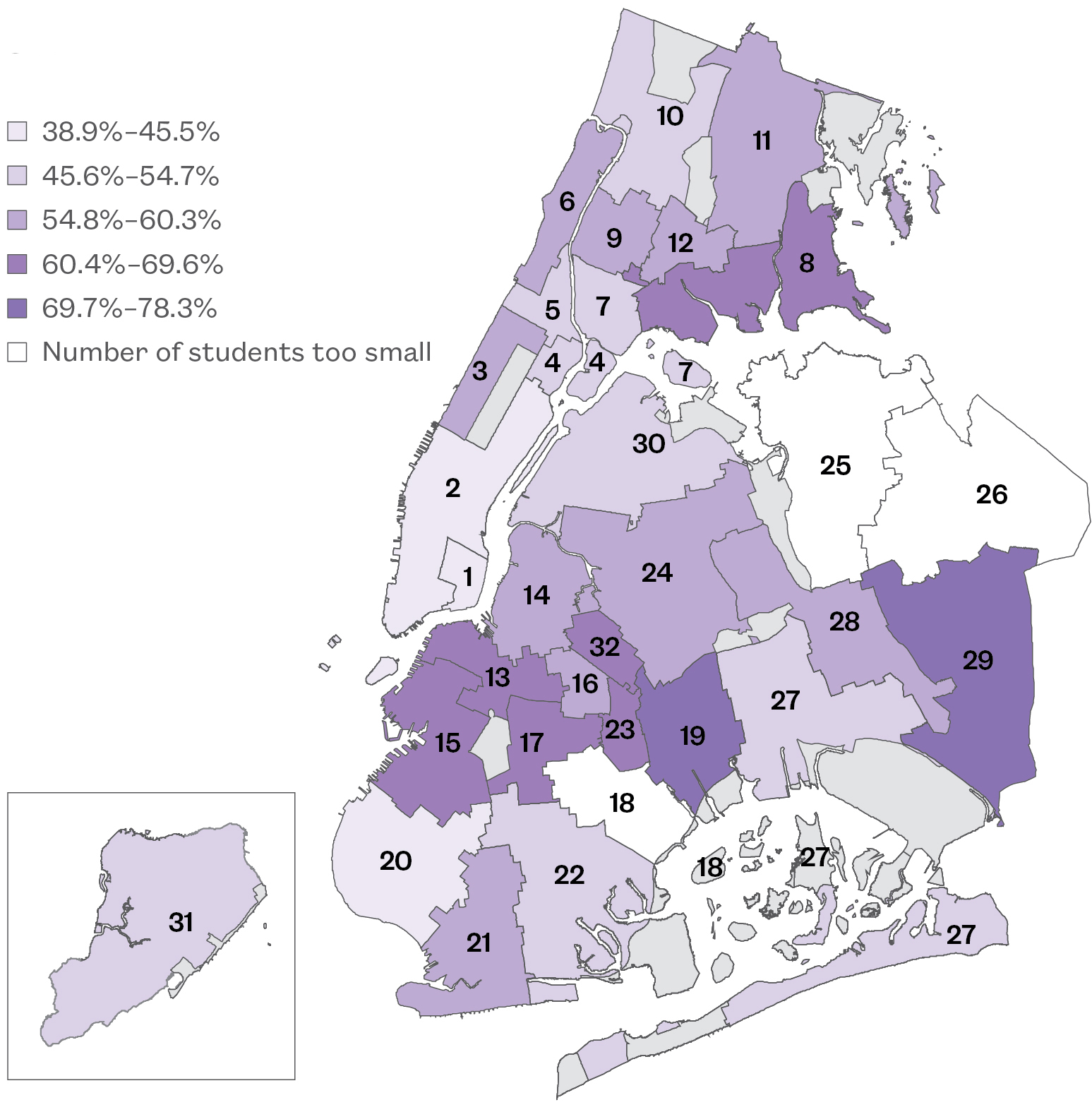

Geographic Patterns of Late IEPs

Share of Homeless Students with Special Needs Who Received IEP Late, by Kindergarten School District

SY 2012–13 to SY 2015–16

Note: Late is defined as after Kindergarten. Data represent a cohort of students who entered Kindergarten in SY 2012–13 and received an IEP at some point during the next four years. Students are categorized according to whether they experienced homelessness at any point during the four-year period. Data are by school district and do not include schools in non-geographic districts. Ns of fewer than 30 students were redacted.

Explore Districts at bit.ly/StudentAtlasApp.

- Citywide, 43% of all students and 54% of homeless students received their IEP late (after Kindergarten). This ranged from 39% of homeless students in Manhattan’s Lower East Side to more than three-fourths (78%) of homeless students in Brooklyn’s East New York/Starrett City. (Districts 1 and 19)

- Queens Village saw the greatest disparity in the late IEP identification rates between homeless and low-income housed students of any school district, with a 50 percent higher rate. (District 29)

- By borough, students with special education needs who experienced homelessness were at the greatest risk for receiving a late IEP in Brooklyn, while those in Staten Island schools had the lowest risk (60% and 46%).

Early identification and support of special education needs is critical to students’ success in school. Learning from identification supports in districts where homeless students are identified earlier and sharing best practices to benefit homeless students in every City school district is critical.

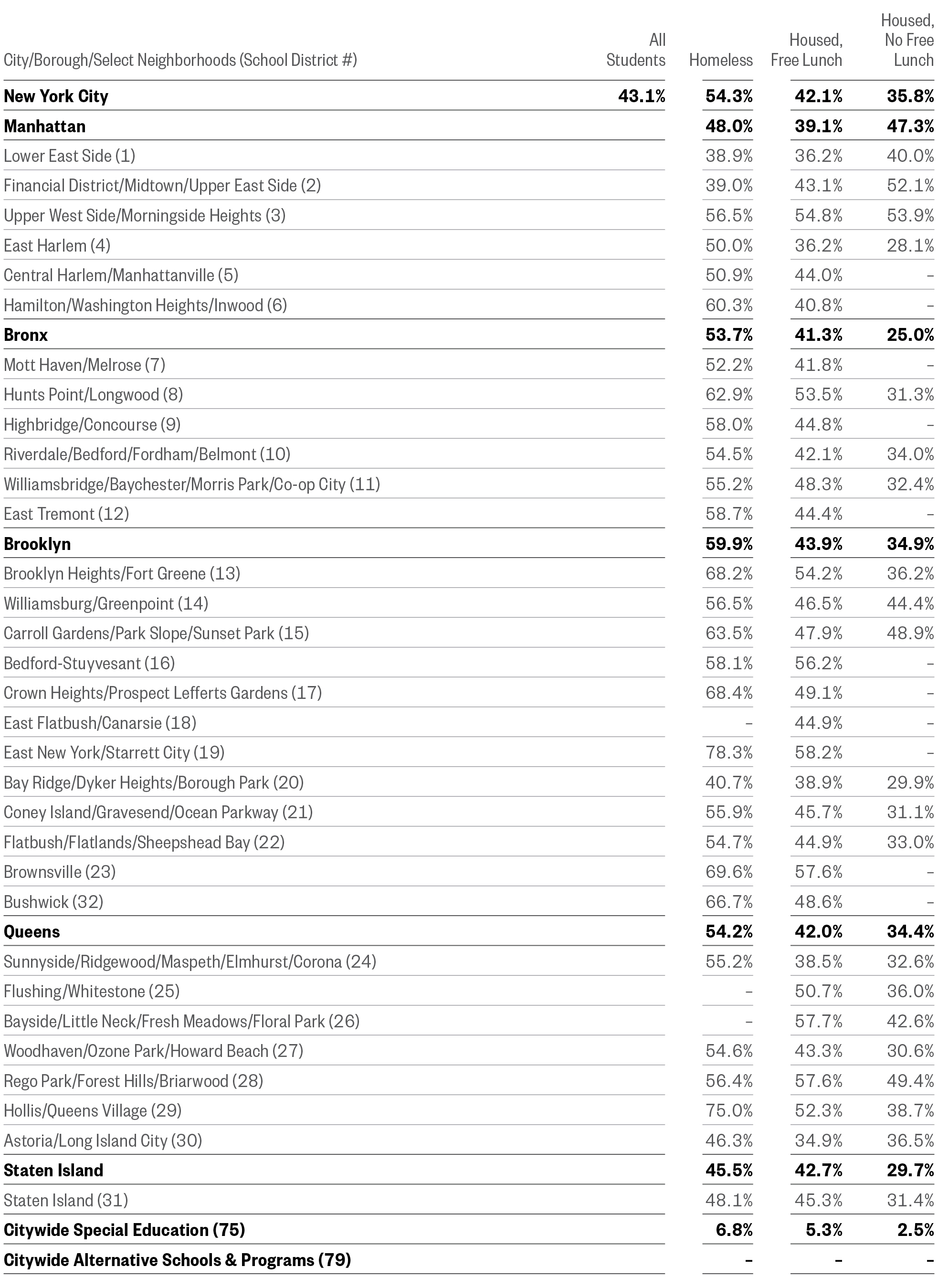

Late IEP Identification

SY 2012–13 to SY 2015–16

Note: Late is defined as after Kindergarten. Data represent a cohort of students who entered Kindergarten in SY 2012–13 and received an IEP at some point during the next four years. Students are categorized according to whether they experienced homelessness or were eligible for free lunch at any point during the four-year period. Data by school district do not include schools in non-geographic districts, so borough and district total percentages may differ. Ns of fewer than 30 students were redacted. Homeless, doubled up and homeless, in shelter categories are not included due to small sample size.

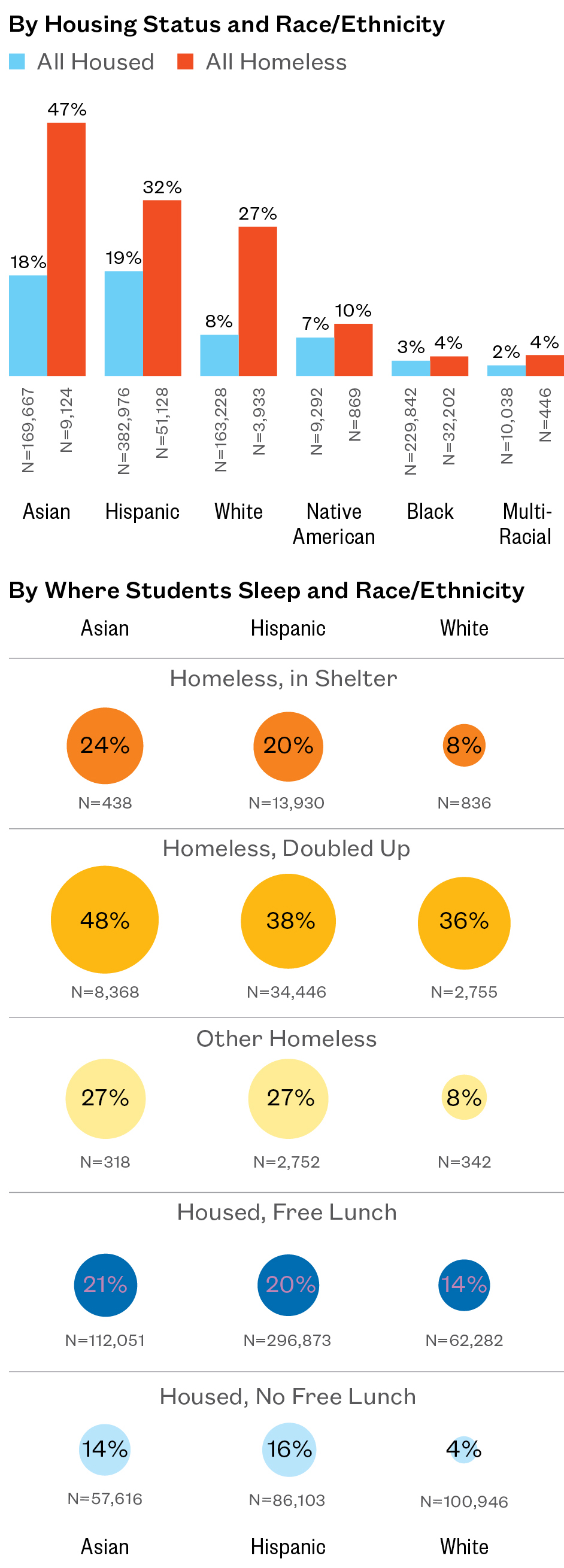

The Intersection of Homelessness and English Language Learners

- Close to one in four (24%) homeless students in New York City were English language learners (ELL) in SY 2015–16. By comparison, just 14% of all students citywide were identified as having ELL needs.

- More than 23,000 NYC public school students who were English language learners had been homeless. The majority of these ELL students who were homeless spoke Spanish as the primary language with their families (72%).

- Spanish was the primary language for 16,500 students experiencing homelessness, while over 1,100 students each spoke Bengali and Mandarin. Other common languages for ELL students who were homeless included Arabic, Chinese (Miscellaneous), Haitian Creole, Cantonese, French, Urdu, Russian, and Uzbek, each of which had more than 100 speakers.

The New York City Department of Education provides educational services to students who speak a language other than English at home. Students who are not proficient in English may receive instruction in a bilingual or dual language setting, or English instruction with additional support in their home language.

English Language Learners

SY 2015–16

Note: “Formerly Homeless” includes students who were housed during SY 2015–16 but were homeless at any point during SY 2010–11, SY 2011–12, SY 2012–13, SY 2013–14, and/or SY 2014–15.

- As homelessness increases citywide, the number of homeless students with English language learning needs has grown by 58%. For housed students, the number decreased by 9%.

- One in every six ELL students was homeless in SY 2015–16. The majority (82%) of homeless students with ELL needs were living doubled up.

Homeless English Language Learners in New York City Public Schools

Number of ELL Students in New York City Public Schools

SY 2010–11 to SY 2015–16

Note: In earlier school years, the total number of “unsheltered” students may be less reliable than other categories. “All homeless” includes all categories of homelessness.

Homeless Students Remain in ELL for Longer

- Not only were homeless students more likely to have ELL needs, but they were also more likely to be identified as ELL for longer than their housed peers who were both low income and non-low income.

- Of students who were identified as having ELL needs in Kindergarten, 75% of homeless students still had ELL needs after two years compared to 65% of low-income housed students and just 29% of non-low-income housed students.

- More than 40% of homeless ELL students still had ELL needs after six years compared to one-third of low-income housed students and only 4% of non-low-income housed students.

Students identified as English language learners take an English proficiency test every year to determine whether they still require additional services.

English Language Learners

Percent of Students Identified with ELL Needs in Kindergarten Who Were Still Identified as ELL in Subsequent Years, by Year

SY 2010–11 to SY 2015–16

Note: Data represent a cohort of students who entered Kindergarten in SY 2010–11 and received ELL services that year. Students are categorized according to whether they experienced homelessness at any point during the five-year period.

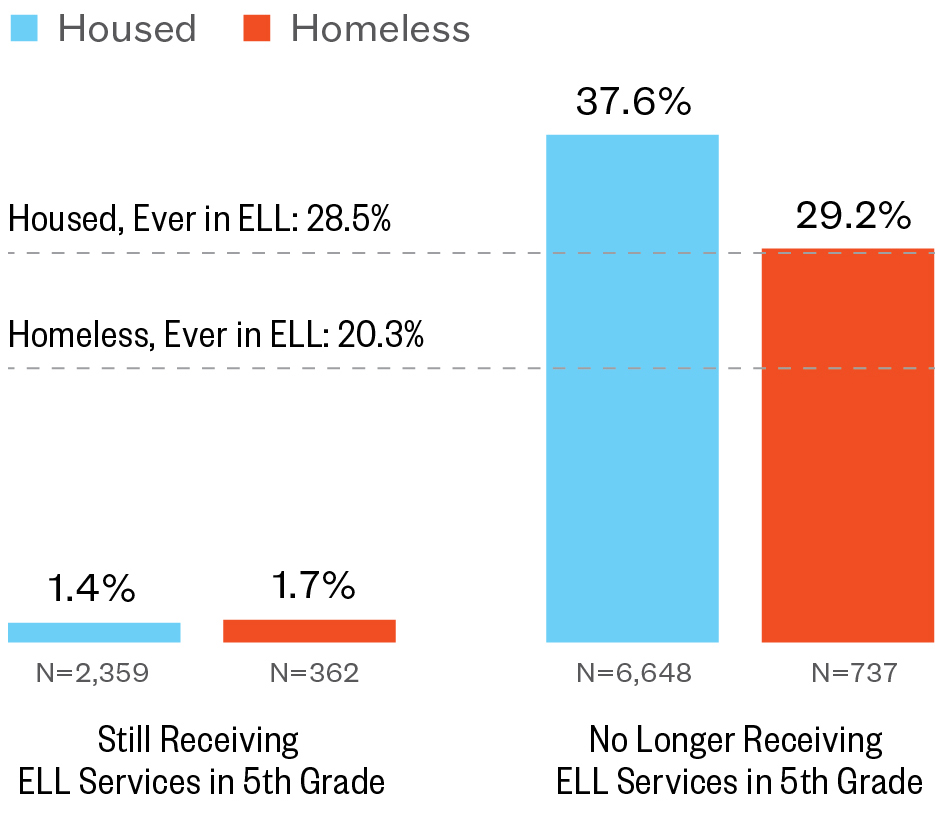

Homeless Students Who Exit ELL Score Proficient More Often

- Overall, English language learners struggle more with academic achievement, scoring proficient on their State assessments at lower rates than students without ELL needs. Just 1.4% of all housed English language learners scored proficient on their 5th grade English Language Arts State assessment in SY 2015–16 compared to 38% of housed students no longer receiving ELL services.

- Homeless students who had English language learning needs in Kindergarten and were able to exit ELL programs by the end of elementary school passed their 5th grade English Language Arts State assessment at approximately the same rate as the overall citywide housed average. (29%)

- Meanwhile, homeless students who were still identified as ELL six years later scored proficient at a rate of just 1.7%.

Considering the high degree of overlap between students with ELL needs and those experiencing housing instability, it is critical to ensure that ELL programs take into account the attendance challenges and high mid-year transfer rates faced by homeless students.

5th Grade State Assessment Proficiency Rate for Students Still in ELL

Percent of Students Who Scored Proficient on State English Language Arts Assessment Among English Language Learners Identified in Kindergarten, by Whether They Still Were Identified as ELL

SY 2015–16

Note: Data represent a cohort of students who entered Kindergarten in SY 2010–11 and received ELL services that year. Students are categorized according to whether they experienced homelessness at any point during the six-year period. The housed, ever ELL and homeless, ever in ELL average include students who were ever identified as ELLs over the six-year period.

Geographic Patterns of English Language Learners

Percent of Homeless Students Who Are English Language Learners, by School District

SY 2015–16

Note: Data are by school district for SY 2015–16 and do not include schools in non-geographic districts.

Explore Districts at bit.ly/StudentAtlasApp.

- One in four (24%) homeless students overall had English language learning needs in SY 2015–16.

- By district, the share of homeless students with ELL needs ranged from just 5% of homeless students in Bedford-Stuyvesant to over half (52%) of homeless students in Bay Ridge. (Districts 16 and 20)

- ELL needs differed by housing status as well. Bay Ridge, Brooklyn had the widest disparity, with 55% of doubled-up students having ELL needs compared to just 18% of students living in shelter. (District 20)

- By borough, students living doubled-up had the highest ELL rates in the Bronx and Queens at 34% and 35%. Meanwhile, Staten Island students living doubled up had the lowest rate at 15%.

Percent of Students Who Are English Language Learners

SY 2015–16

Note: Data by school district do not include schools in non-geographic districts, so borough and district total percentages may differ. Ns of fewer than 30 students were redacted.

English Language Learners by Ethnicity

- English language learner rates varied greatly by students’ ethnicity, with Asian, Hispanic, and white homeless students seeing the highest rates of ELL needs. Close to half (47%) of Asian students who were homeless had English language learning needs in SY 2015–16—over twice the rate of housed Asian students (18%).

- Across ethnicities, doubled-up students had the highest ELL rate of all housing groups.

- Almost one-third of both Hispanic and white students who were homeless (32% and 27%) had ELL needs, compared to 19% of housed Hispanic students and 8% of housed white students.

ELL Rates by Race and Ethnicity

Percent of Students Who Were English Language Learners, by Race/Ethnicity and Grade Level

SY 2015–16

Note: “Other Homeless” includes students who were awaiting foster care, paying for a hotel/motel outside of the shelter system, or living in another temporary and/or unsuitable housing situation.

Where are Homeless English Language Learners by Ethnicity?

Density of English Language Learners by Ethnicity, with Top Languages Spoken

SY 2015–16

Note: Language refers to the language that students speak with their family. Chinese (Miscellaneous) refers to students whose primary language is Chinese.

- English language learners overall were concentrated in the south and west Bronx, central Queens, and south Brooklyn.

Examining ELL rates among homeless students by ethnicity shows where potential services could be coordinated and tailored to meet the different linguistic needs of homeless students.

Download Section 3 PDF

To explore homelessness in New York City schools, try our interactive map.

To learn more about the educational outcomes of homeless New York city students, try our Student Atlas app.

Return to top.

Section 4

Educational Achievement of Homeless Students: English Language Arts (ELA) and Math State Assessment Proficiency

“In our school, the [experiencing homeless] kids with the most adjustment and behavior issues are the young ones. They really have trouble settling in. They’re not used to focusing. They have trouble acclimating to the environment. We have kids who don’t want to stay in the classroom, who literally exit the classroom. Sometimes they have problems completing assignments if you send them home, so we try to do them in school.”

—Former Principal, Community School in Brooklyn

“One middle school student [age 13] said that traveling from the Bronx to school in Brooklyn caused him to go from an A average in English to a 67% due to being late. His younger brother [age 8] really struggled to get up in time to get on the train for school, and he would often fall asleep in class. Last year, his teacher became concerned that he might have a sleep disorder because he was constantly nodding off. He missed out on a lot of valuable classroom instruction and he was moved to a special education classroom.”

—Social Work Director, Partnership with Children, working in New York City public schools

The effect of housing instability on student performance is clearly demonstrated once students begin taking State-mandated math and English tests in the third grade. These tests receive significant political and media attention, yet the outcomes of homeless students and those with a history of housing instability are generally overlooked. Poor performance in school is known to correlate with students’ future academic outcomes, and meeting the educational needs of homeless students is critical to give these students the opportunity to learn on pace with their peers.

What’s New?

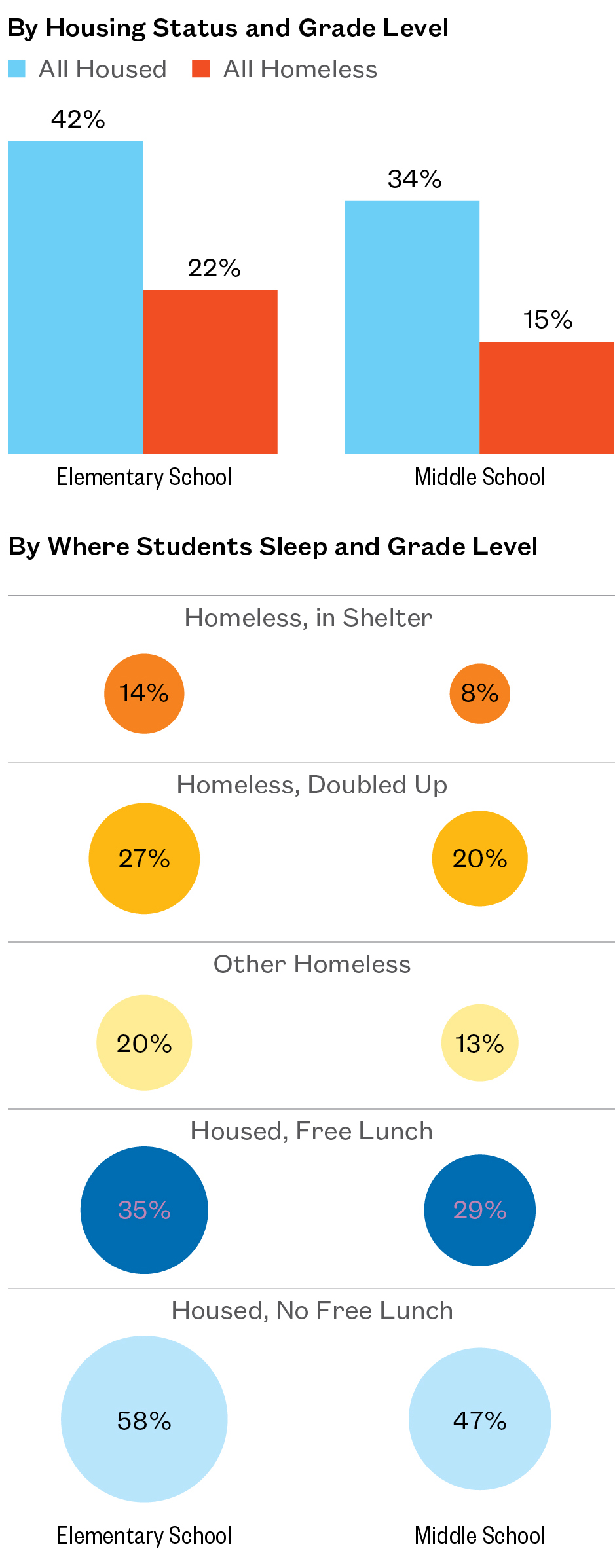

- Homeless students living in shelter were more at risk academically than their housed or other homeless peers. Among middle schoolers, just 8% of students in shelter scored proficient in math, a rate four times lower than housed students overall (34%).

- Amidst citywide policy and curricula changes over time, achievement gaps by housing status persisted. Homeless students scored proficient in ELA at roughly half the rate of housed students overall (21% to 40% in SY 2015–16).

Policy Considerations

- Achievement gaps must be looked at not only between homeless and housed students overall, but also among students who have been homeless living in different settings. Children who have lived in a shelter consistently see lower academic proficiency than their doubled-up peers. Targeting academic supports to students in shelter is needed to reduce these students’ academic risk.

- Students who have a history of homelessness see virtually the same level of academic risk as currently homeless students and should remain eligible for additional supportive and academic services even after moving into permanent housing.

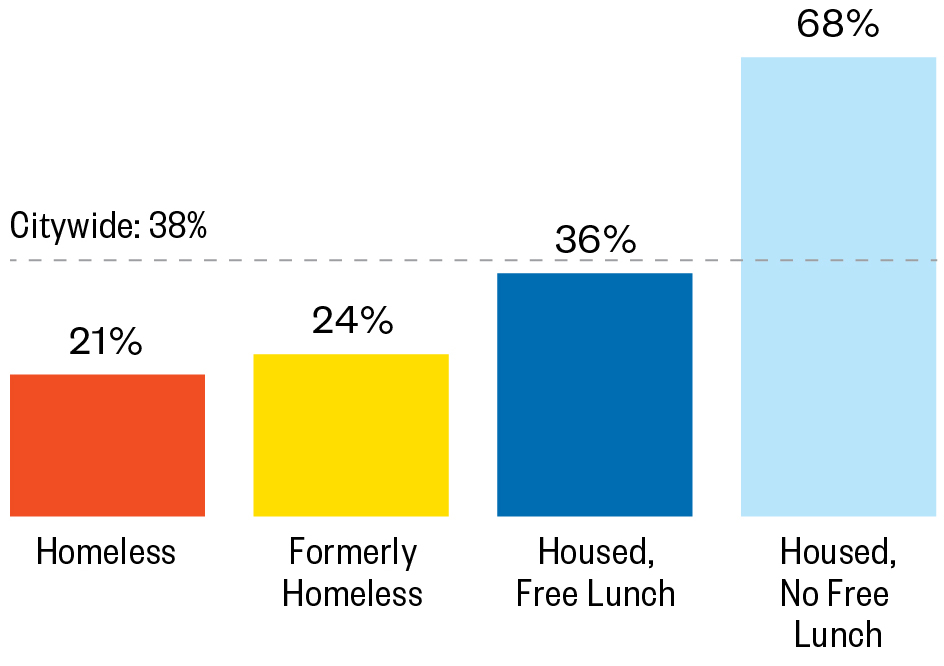

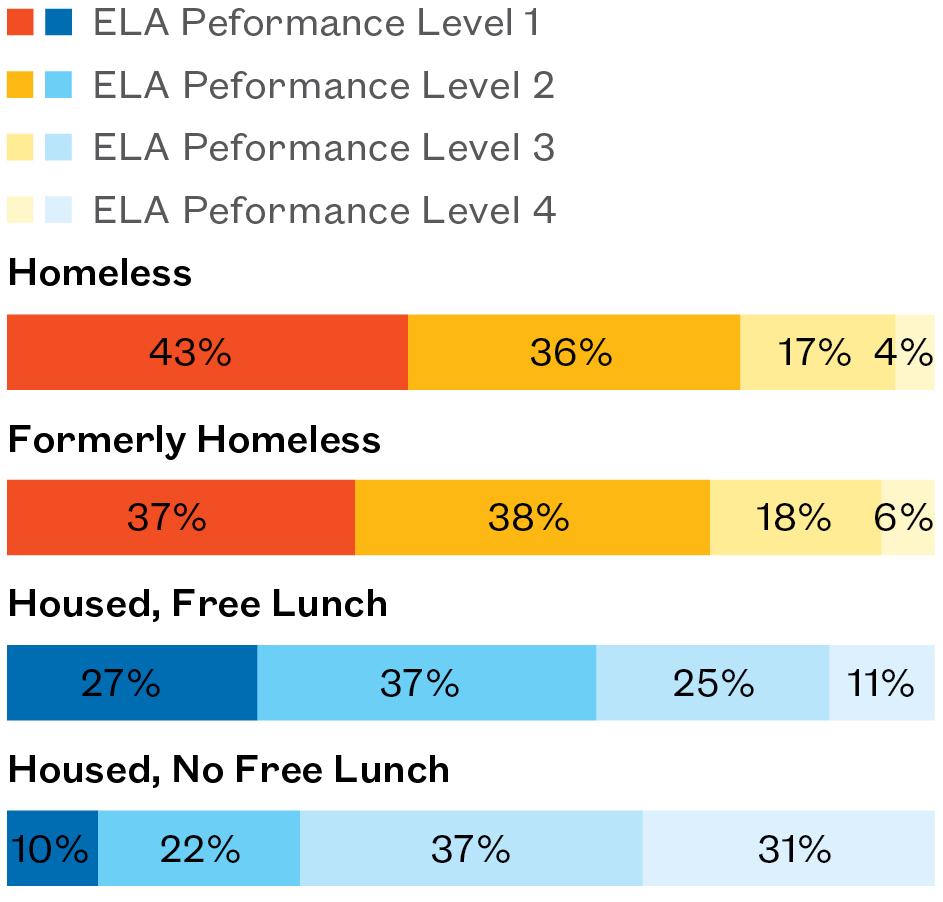

English Language Arts Achievement Among Homeless Students

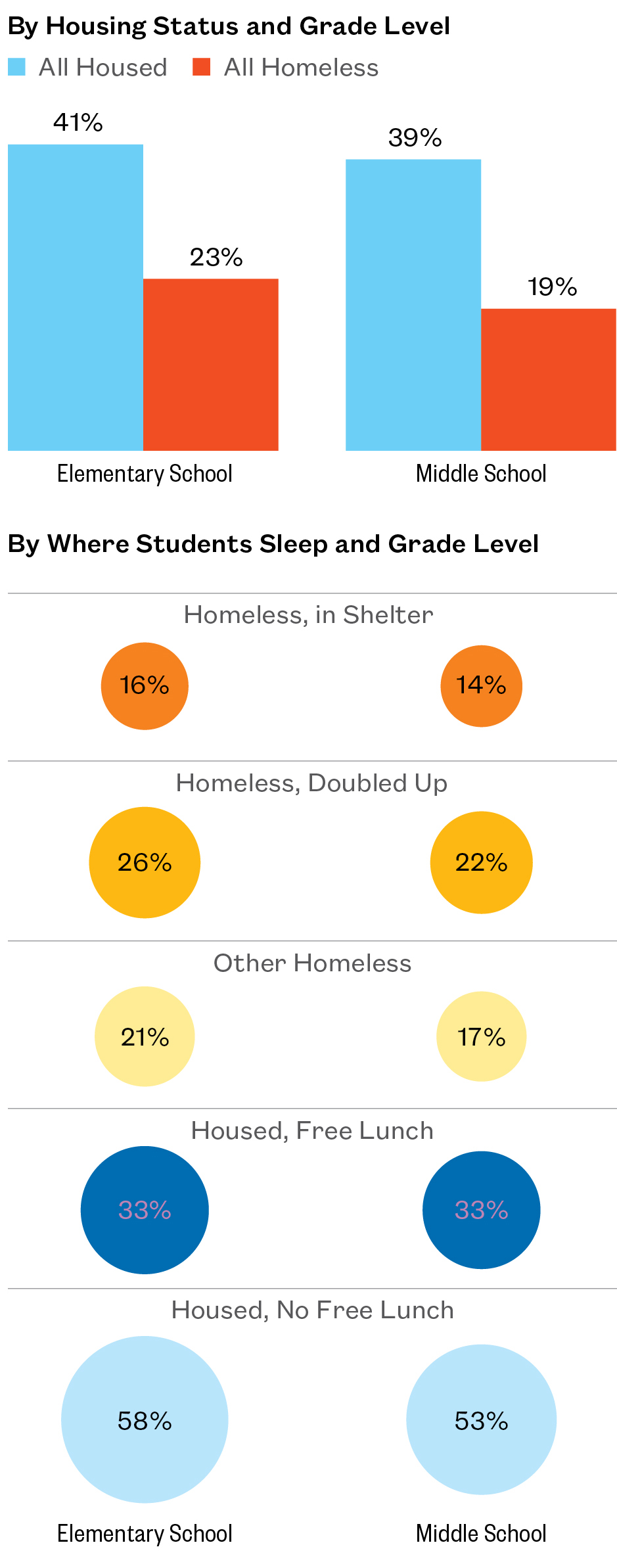

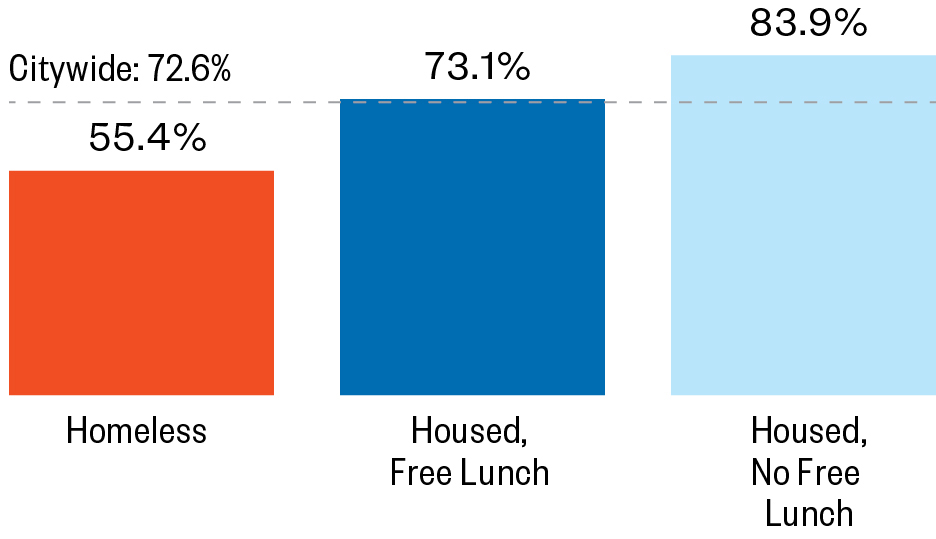

- One in five homeless students scored proficient in ELA (21%) compared to roughly a third of low-income housed students (36%) and two-thirds of non-low-income housed students (68%).

- Homelessness has a lasting impact on school achievement. Students who were currently housed but had experienced homelessness (formerly homeless) met ELA grade-level standards at roughly the same rates as their currently homeless peers (24% to 21%).

The consistency with which formerly homeless students perform far below their classmates even after they are stably housed indicates how difficult it can be for students to catch up once they have fallen behind. Ensuring that homeless students receive ongoing supports even after they become housed is critical to closing this achievement gap.

3rd–8th Grade State English Language Arts Test Proficiency Rates

SY 2015–16

Note: “Formerly Homeless” includes students who were housed during SY 2015–16 but were homeless at any point during SY 2010–11, SY 2011–12, SY 2012–13, SY 2013–14, and/or SY 2014–15.

- Homeless students were most likely to receive a level 1 score (43%)—indicating that they performed well below proficiency standards. Just 27% of low-income housed students and 10% of non-low-income housed students received that score.

- Meanwhile, only 4% of homeless students and 6% of formerly homeless students scored at proficiency level 4—the highest level—compared to 11% of low-income housed students and 31% of non-low-income housed students.

3rd–8th Grade State English Language Arts Test Proficiency Rates by Housing Status

SY 2015–16

Note: Performance levels 1 and 2 indicate a student performed well below or partially below proficiency on the New York State Department of Education English Language Arts assessment, and levels 3 and 4 indicate a student performed at proficiency or higher. “Formerly Homeless” includes students who were housed during SY 2015–16 but were homeless at any point during SY 2010–11, SY 2011–12, SY 2012–13, SY 2013–14, and/or SY 2014–15. Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding.

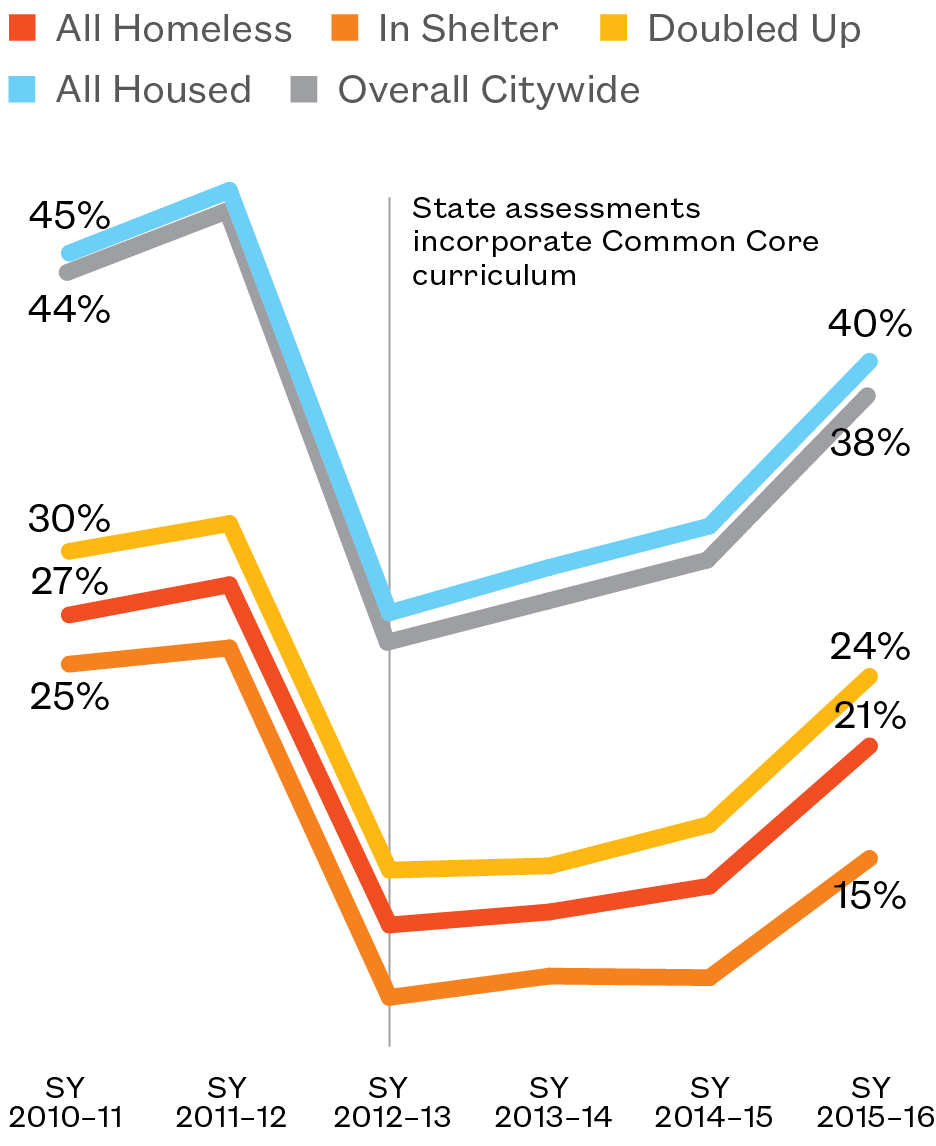

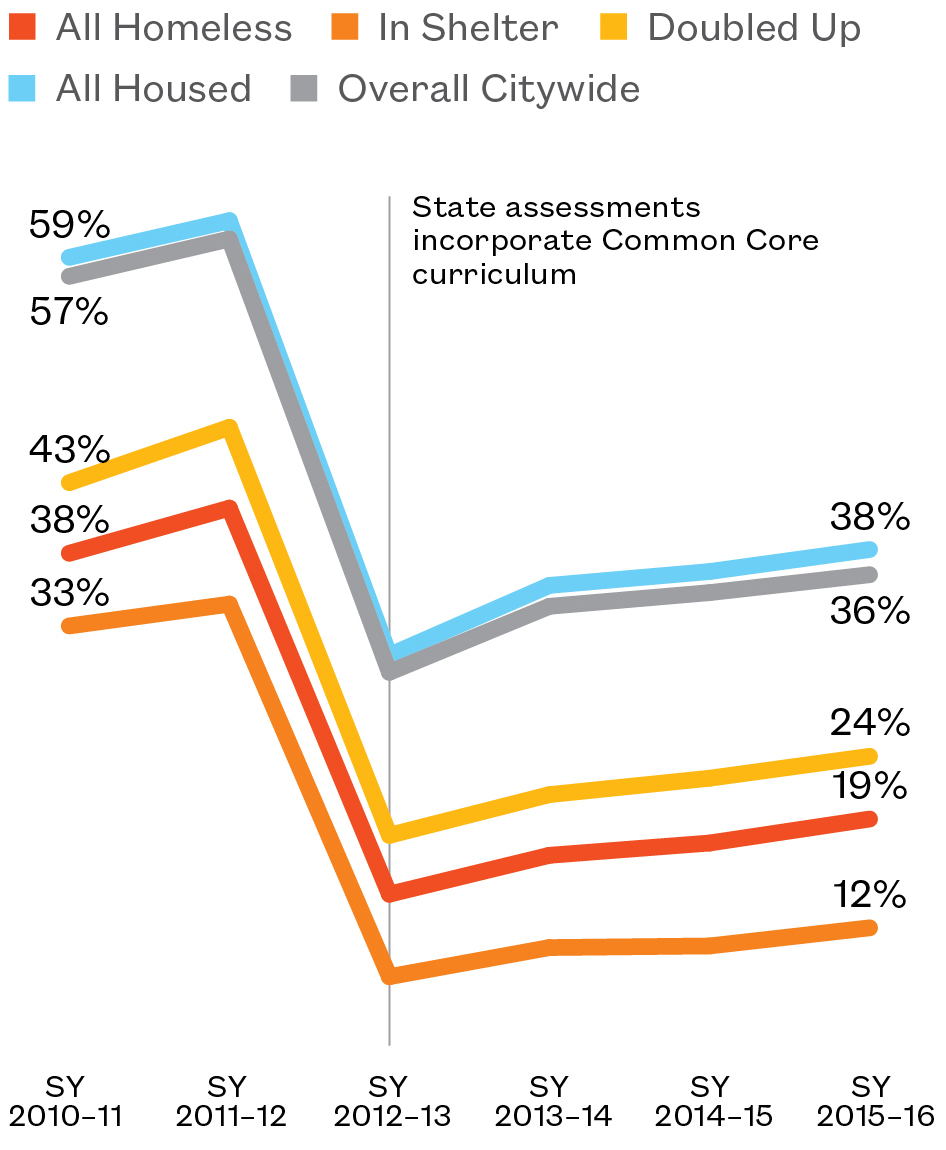

- With the adoption of Common Core standards into 3rd–8th grade State assessments in SY 2012–13, proficiency rates overall dropped by 16 points in ELA. Three years later in SY 2015–16, students were given unlimited time, allowing students to work at their own pace; that year, citywide ELA proficiency rates rose by 6 points.

- Amidst citywide policy and curricula changes, achievement gaps by housing status persisted. Homeless students scored proficient at roughly half the rate of housed students overall (21% to 40% in SY 2015–16).

- Homeless students living in shelter faced the greatest academic risk compared to their housed or other homeless peers. Only 15% of all students in shelter scored proficient on their 3rd–8th grade ELA assessment, roughly one-third the rate of housed students overall and two-thirds the rate of their classmates living doubled up (40% and 24%).

- Homeless students living doubled up scored proficient at roughly half the rate of their housed classmates (24% to 40%).

Changes in Citywide State English Language Arts Test Proficiency Rates by Year

SY 2010–11 to SY 2015–16

Note: SY 2012–13 was the first year that the 3rd–8th grade state assessments incorporated the Common Core curriculum. New York State first adopted the Common Core curriculum in 2010. Students were given unlimited time to complete their assessments starting in SY 2015–16. “All homeless” includes all categories of homelessness.

- Students living in shelter scored proficient on ELA assessments at the lowest rates of any other group, with just 16% of elementary students and 14% of middle schoolers in shelter scoring proficient in ELA—just half the rate of their housed, low-income peers (33% and 33%) and one-fourth the rate of their housed peers who were not low income (58% and 53%).

- By middle school, the proficiency gap between homeless and housed students widened, with housed students scoring proficient at over twice the rate of homeless students. This pattern likely reflects the lingering destabilizing effects of homelessness on children’s education.

Middle school proficiency is a key indicator of high school graduation and future success. Targeting academic supports to students in shelter is needed to reduce these students’ academic risk.

3rd–8th Grade State English Language Arts Test Proficiency Rates

Percent of Students who Scored Proficient on the State English Language Arts Test

SY 2015–16

Note: “Other homeless” includes students who were awaiting foster care, paying for a hotel/motel outside of the shelter system, or living in another temporary and/or unsuitable housing situation.

Geographic Patterns of English Language Arts (ELA) Proficiency

English Language Arts Grade-Level Proficiency Varies by Geography

Grade-Level Proficiency Among Homeless Students: 3rd–8th Grade State English Language Arts (ELA) Test

SY 2015–16

Note: Data are by school district for SY 2015–16 and do not include schools in non-geographic districts.

Explore Districts at bit.ly/StudentAtlasApp.

- Citywide, 38% of all students and 21% of homeless students scored proficient on their 3rd–8th grade ELA assessment. For homeless students, ELA proficiency ranged from a low of 12% in East Tremont in the Bronx to a high of 44% in Bayside, Queens. (Districts 12 and 26)

- In Manhattan, ELA proficiency rates for homeless students ranged from a high of 38% in the Financial District/Upper East Side to a low of 16% in Central Harlem compared to 21% for homeless students overall. (Districts 2 and 5)

- ELA proficiency among homeless students was lowest in some of the areas with the most homeless students overall, including upper Manhattan, the south Bronx, and central Brooklyn. (Districts 1, 4-12, 14, 16, 19, 23, 31, and 32)

3rd–8th Grade State ELA Test Proficiency Rate

SY 2015–16

Note: Data by school district do not include schools in non-geographic districts, so borough and district total percentages may differ. Ns of fewer than 30 students were redacted.

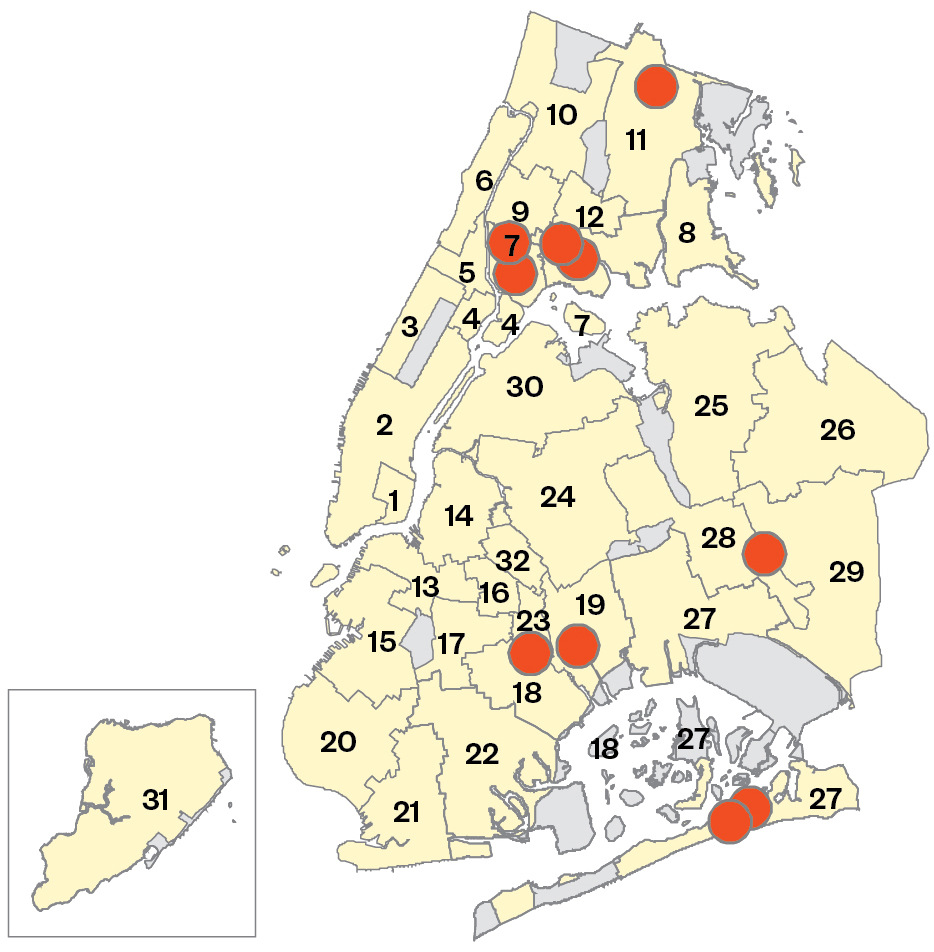

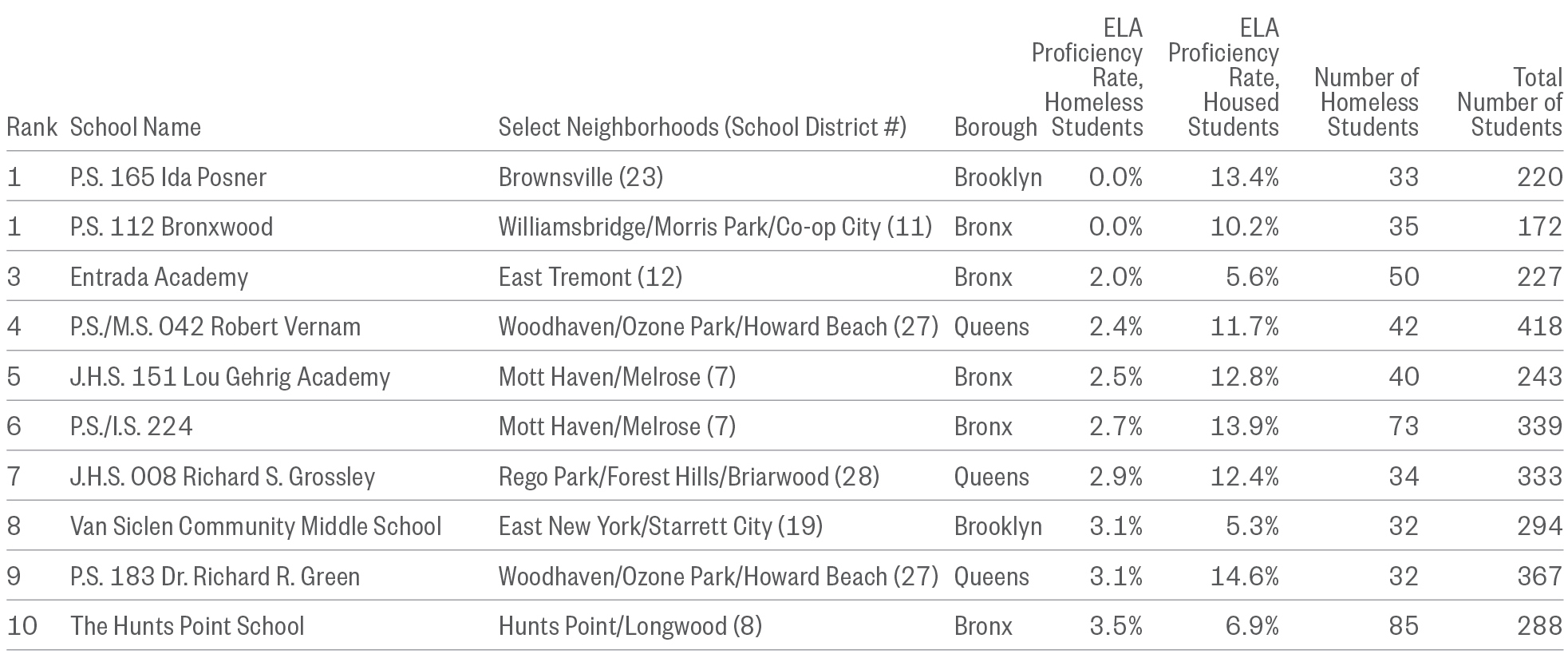

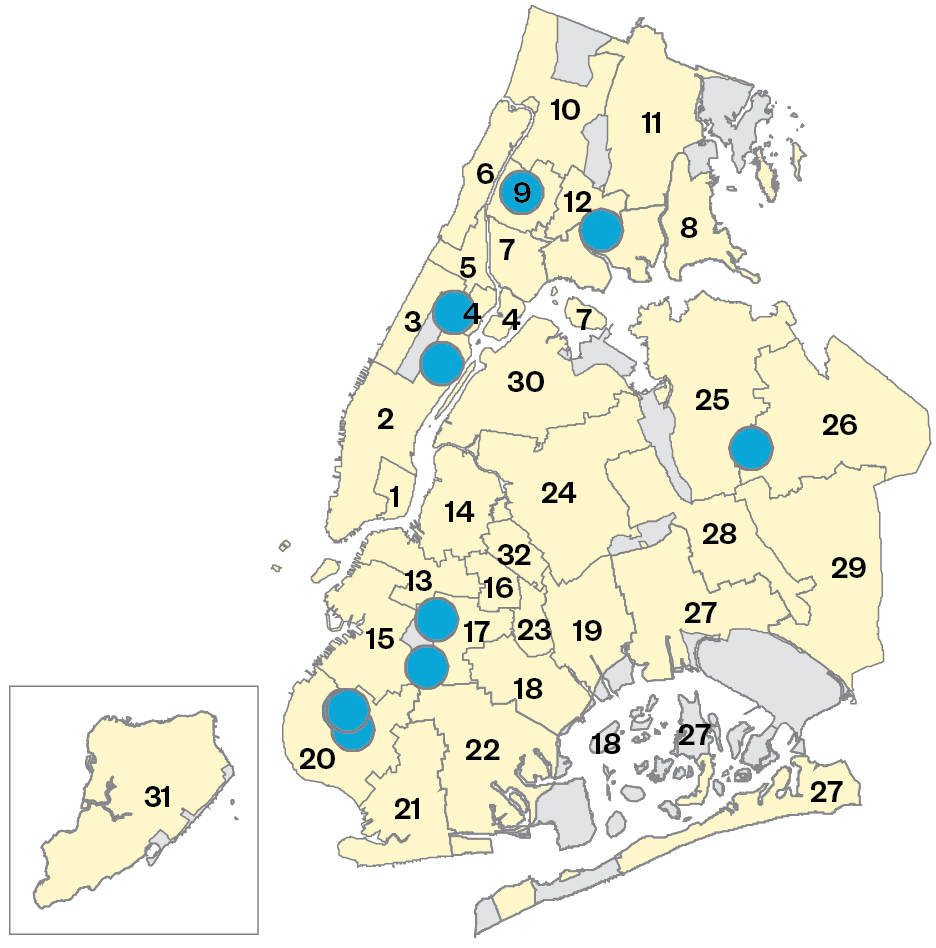

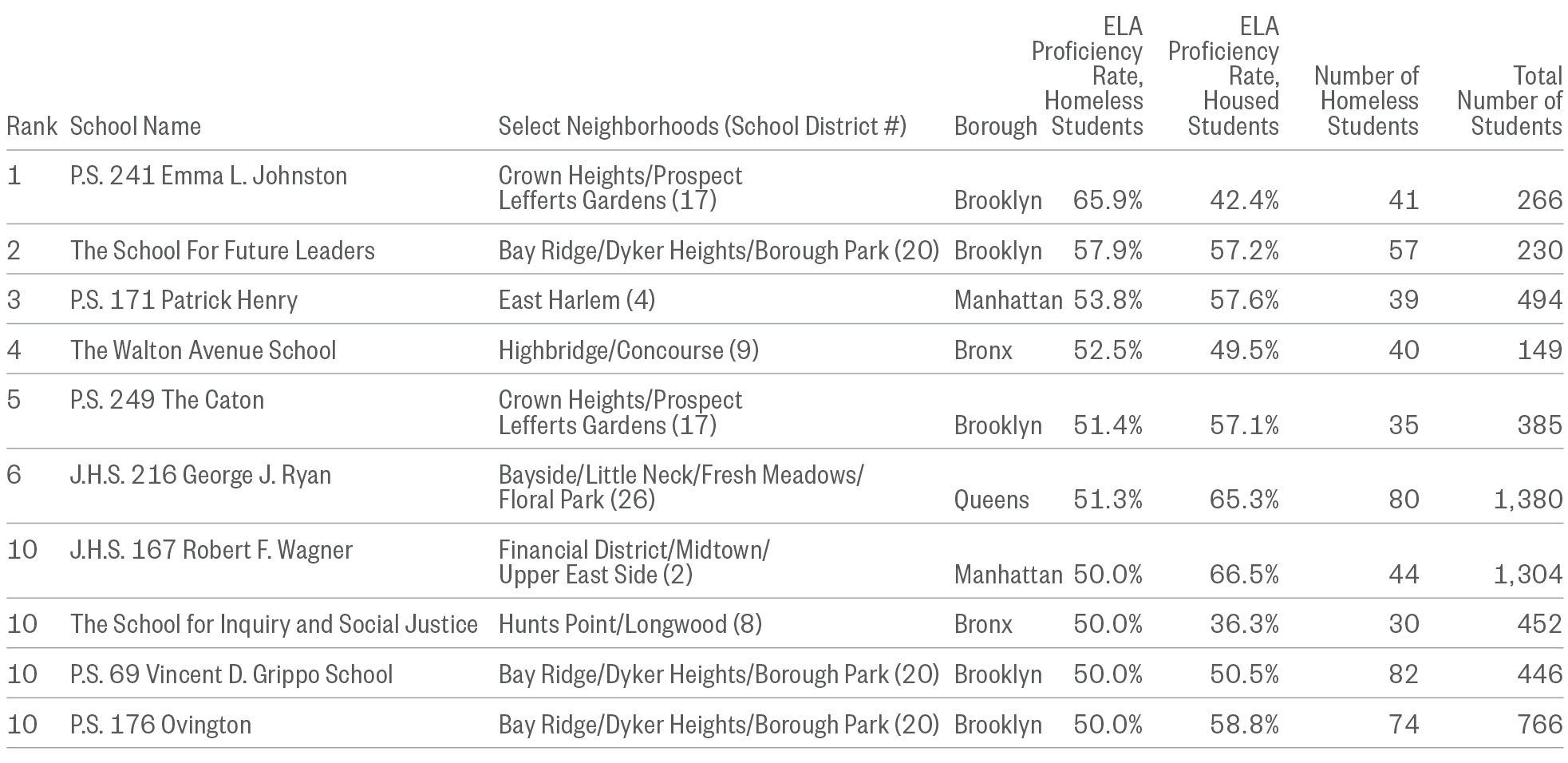

- By school, ELA proficiency rates for homeless students ranged from 0% in two schools—P.S. 165 Ida Posner in Brownsville and P.S. 112 Bronxwood in Williamsbridge—to 66% in P.S. 241 Emma L. Johnston in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. (Districts 23, 11, and 17 respectively)

Top 10 Schools for Lowest Homeless Student ELA Proficiency Rate

SY 2015–16

See schools at bit.ly/MapNYCHomelessStudents

Top 10 Schools with Lowest Homeless Student English Language Arts Proficiency Rate

SY 2015–16

Note: Data are by school district for SY 2015–16 and do not include schools in non-geographic districts.

- At P.S. 241 Emma L. Johnston in Brooklyn’s Crown Heights and The School for Inquiry and Social Justice in Hunts Point in the Bronx, homeless students were proficient in ELA at much higher rates than their classmates who were housed—24 points higher and 14 points higher respectively. (Districts 17 and 8)

Understanding what supports are enabling homeless students to perform at such high rates and translating those to other schools citywide could raise proficiency rates for all students.

Top 10 Schools for Highest Homeless Student ELA Proficiency Rate

SY 2015–16

See schools at bit.ly/MapNYCHomelessStudents

Top 10 Schools with Highest Homeless Student English Language Arts Proficiency Rate

SY 2015–16

Note: Data are by school district for SY 2015–16 and do not include schools in non-geographic districts.

Math Achievement Among Homeless Students

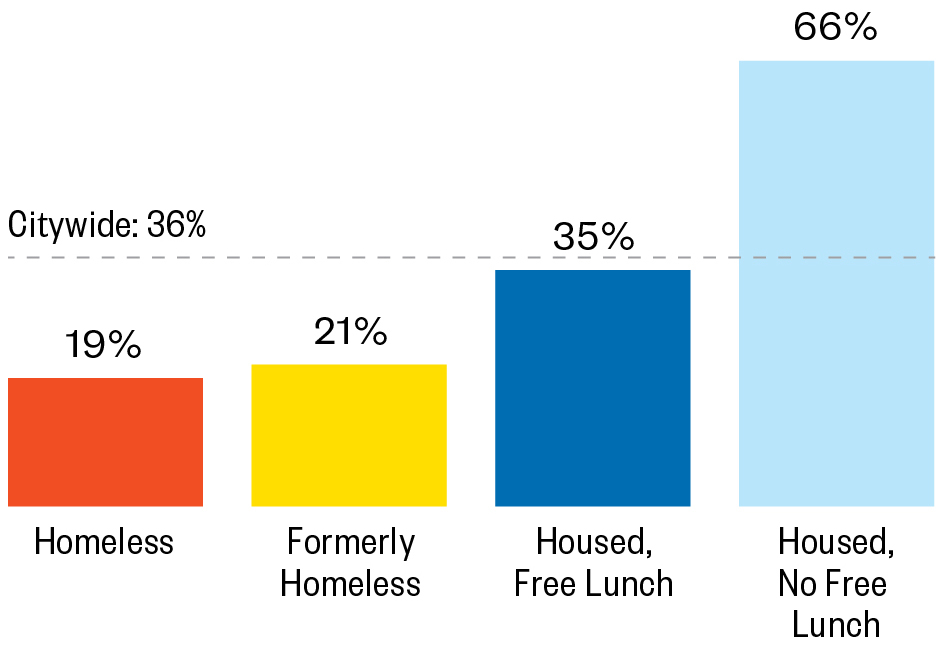

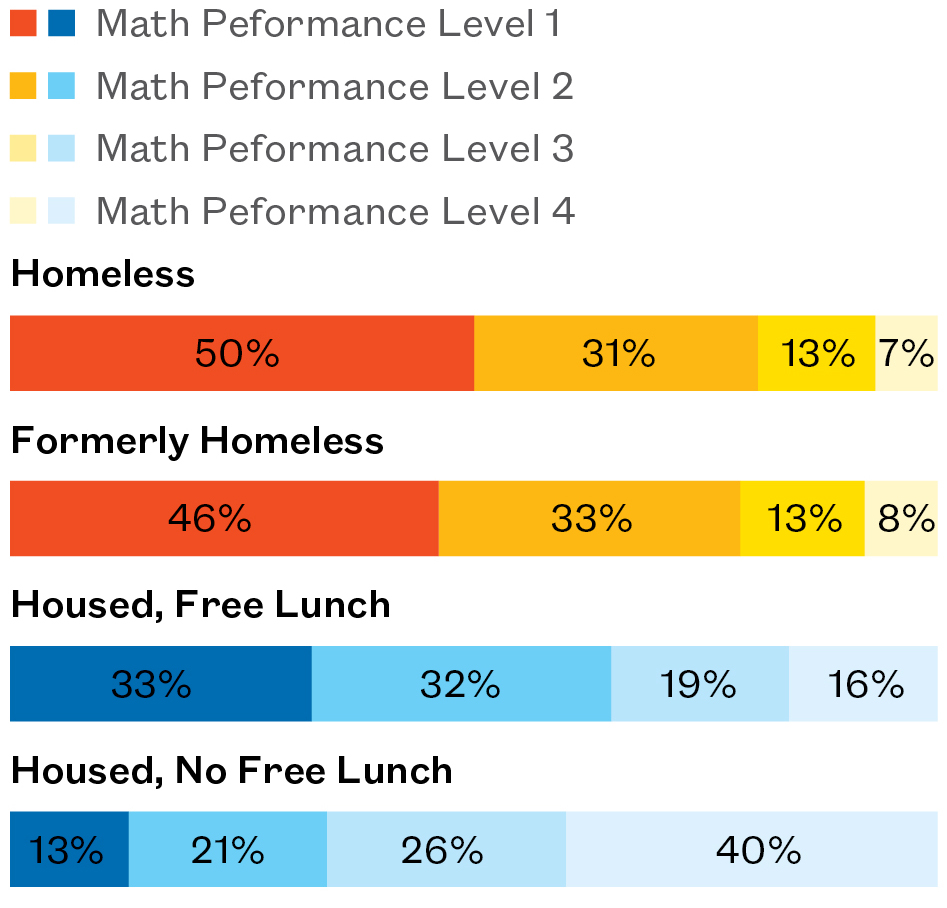

- One in five (19%) students experiencing homelessness scored proficient on their 3rd–8th grade State math assessment compared to roughly a third of low-income housed students (35%) and two-thirds of non-low-income housed students (66%).

- Students who were currently housed but had experienced homelessness (formerly homeless) met grade-level standards at roughly the same rates as their currently homeless peers (21% to 19% in math).

3rd–8th Grade State Math Test Proficiency Rates

SY 2015–16

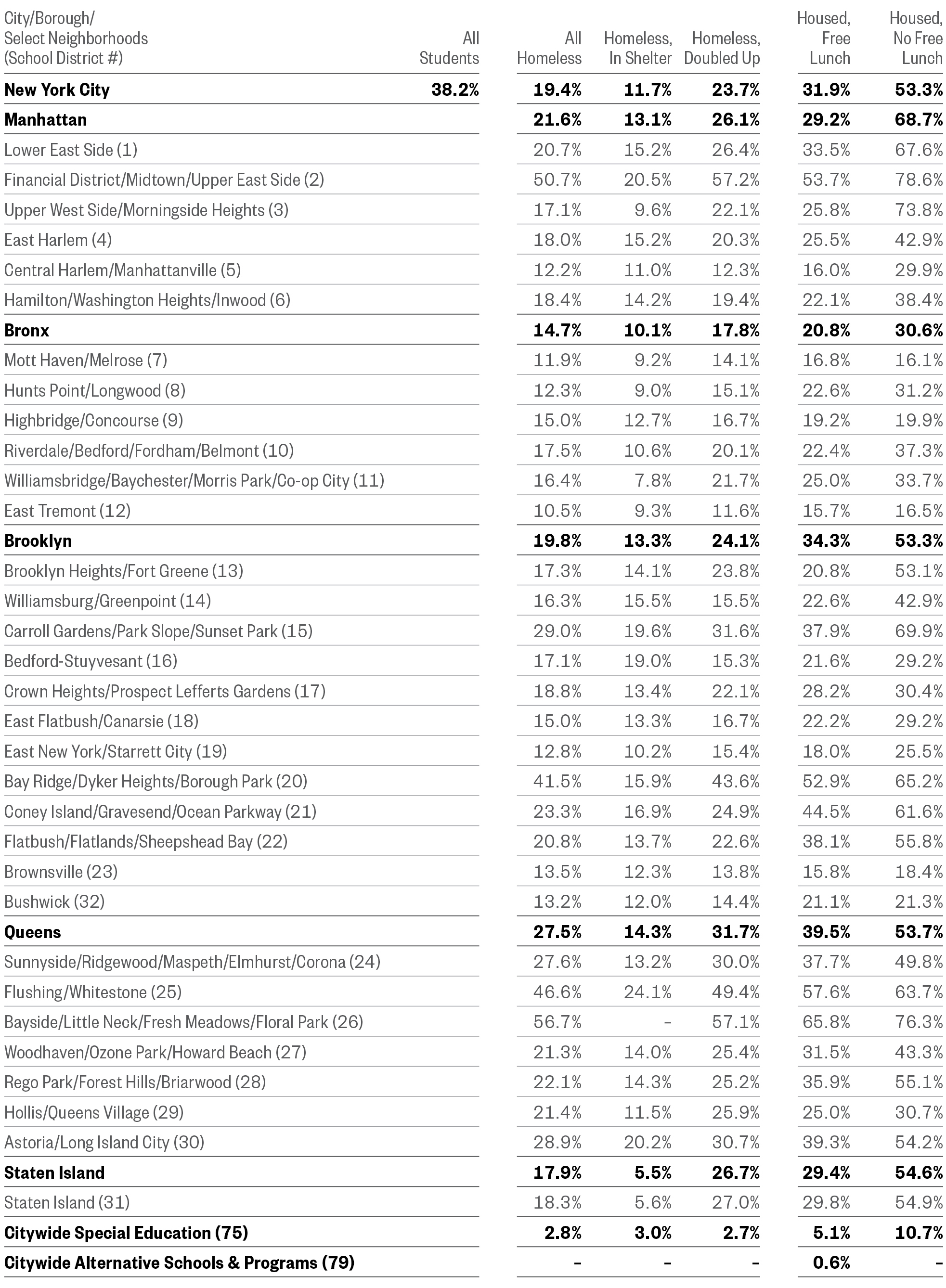

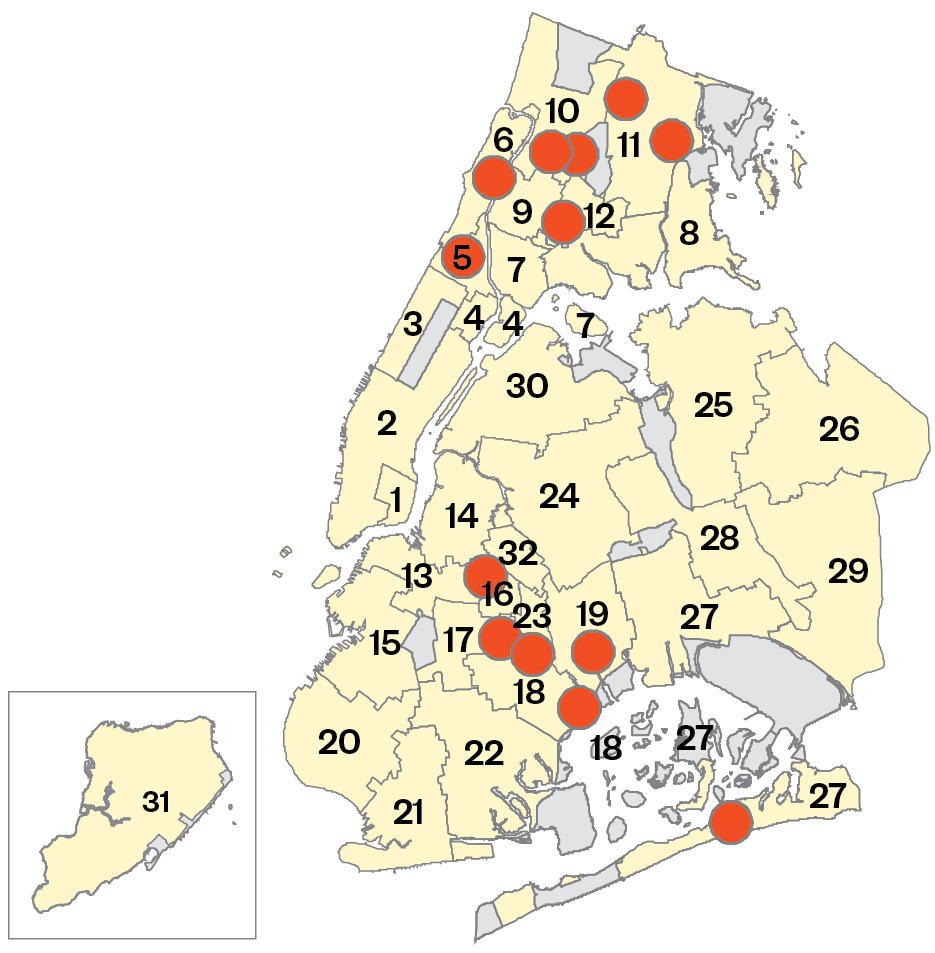

Note: “Formerly Homeless” includes students who were housed during SY 2015–16 but were homeless at any point during SY 2010–11, SY 2011–12, SY 2012–13, SY 2013–14, and/or SY 2014–15.