By Caroline Iosso, Senior Policy Associate; Maribel Maria, Policy Associate; Robyn Schwartz, Policy Advisor

Introduction

Twenty years ago, New York City piloted HomeBase, a community-based assistance program designed to keep families and individuals from entering the City’s then-bursting shelter system. Over the last two decades, this small pilot program would influence national homelessness policy, dictating how federal dollars would be spent and resources would be allocated in NYC and around the nation. When Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg entered office in 2002, the Department of Homeless Services (DHS) Families with Children homelessness census was just under 7,000 families. By the end of his 12 years in office and despite his administration’s attention to the issue, the census was well over 10,000 families. From 2013 onward, the DHS Families with Children census only fell below 10,000 families for a brief period at the tail end of December 2020 into August 2022—a time marked by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and eviction moratorium, which remained in place until January 2022. Given the stubborn and persistent trajectory of family homelessness, the time is ripe to reflect on the past two decades of family homelessness prevention in New York City.

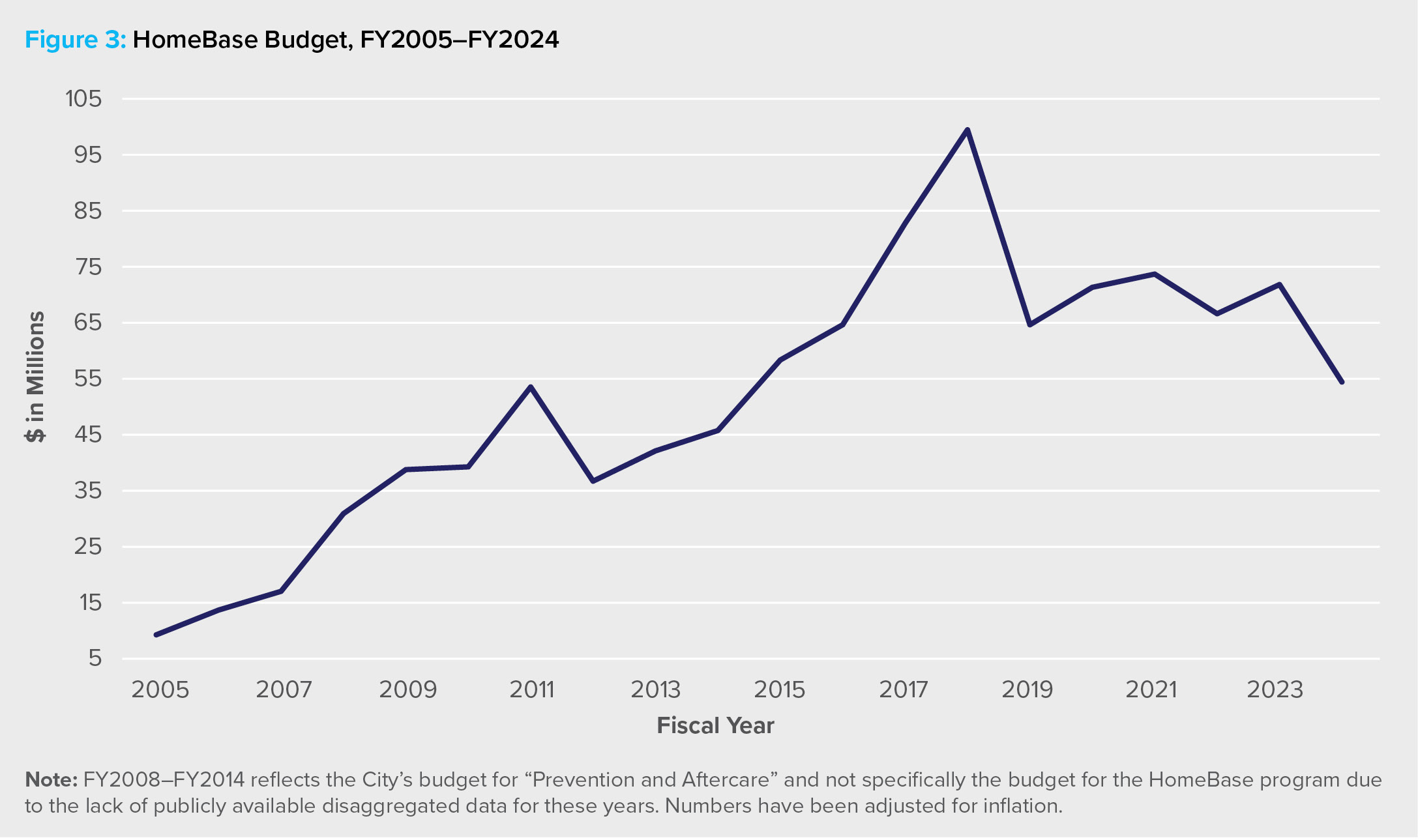

This report will examine the history of HomeBase, how it works to prevent homelessness, and its impact on families with children experiencing housing instability. The program is not inexpensive—the City has spent approximately $1 billion (adjusted for inflation) over its lifetime—but it’s a small percentage of the over $2 billion that has been budgeted for the Department of Homeless Services every year since FY2018, especially since prevention is a critical and necessary piece of how New York City can seek to reduce the shelter population.1 In the coming sections, we will look at what evaluations exist of HomeBase and where the gaps are in the public’s understanding of the program. By filling in these gaps, policymakers can start to design ways to strengthen our city’s safety net, preventing families from losing stable housing and entering the shelter system.

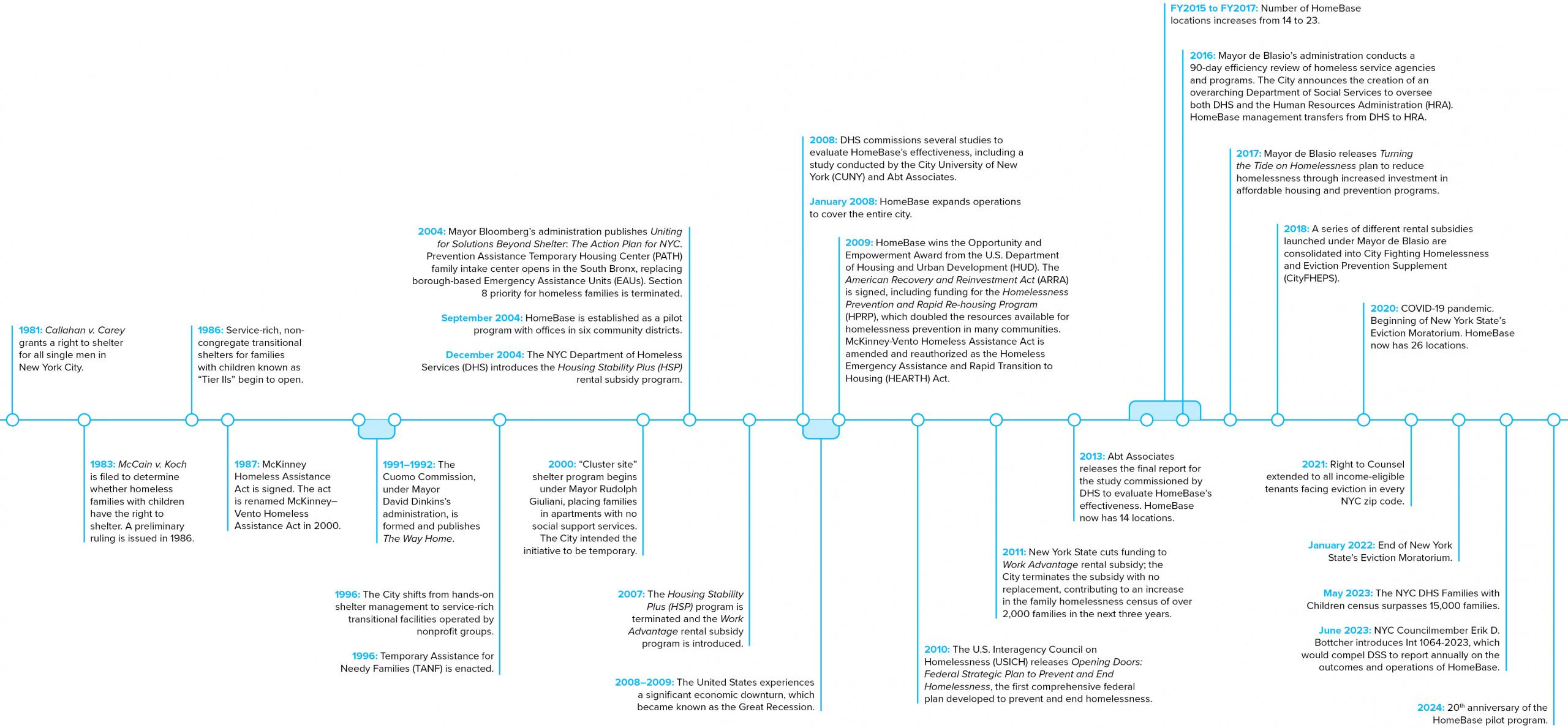

Timeline of Prevention and Family Homelessness Policies in New York City, 1980s–Today

Click timeline to enlarge or download PDF HERE.

Click timeline to enlarge or download PDF HERE.

A Brief History of HomeBase and Homelessness Prevention Measures in NYC

The HomeBase program was piloted in 2004 in New York City. Prior to its existence, New York City’s approach to prevention largely reflected national trends, which undervalued addressing the causes of homelessness. Those involved in homeless services and policy research before the 2000s state that it was rare for local plans addressing homelessness to “extend” to preventing homelessness.2 In New York City, despite a recognition by some professionals working in homeless services of the importance of access to supportive services prior to entering shelter, integrating these policies was difficult. In The Way Home, a pivotal policy-reforming report published in 1992, for example, the NYC Commission on the Homeless (also known as the Cuomo Commission) detailed prevention efforts that focused on shelter allowances, rental arrears payments, and other “services and supports.”3 Despite these calls to strengthen preventive services, issues with implementation of these ideas meant that the City’s response to homelessness continued to focus on supporting those who had already lost their housing.4 Thus, before the development and implementation of HomeBase, the New York City government relied on short-term access to low-income housing without other supports to relieve homelessness.5 This one-sided, housing-only strategy proved limited in effect, as the homelessness census, particularly the number of families in New York City Department of Homeless Services (DHS) shelters, more than doubled over the decade.

Laying the Foundation: Research and Piloting of HomeBase

Finally, in the early 2000s, Mayor Bloomberg’s administration took seriously the record demand for shelter and decided to shift its focus to prevention. To develop an effective response, a group of City agencies contracted the Vera Institute of Justice to conduct research on families experiencing homelessness in New York City. This research began in the spring of 2003, and its intent was to help the City learn why families become homeless and how preventative approaches could stem the increase of families into the shelter system. Its recommendations lent support to the neighborhood-based strategy that DHS employed in a request for proposals that would establish HomeBase pilots.6

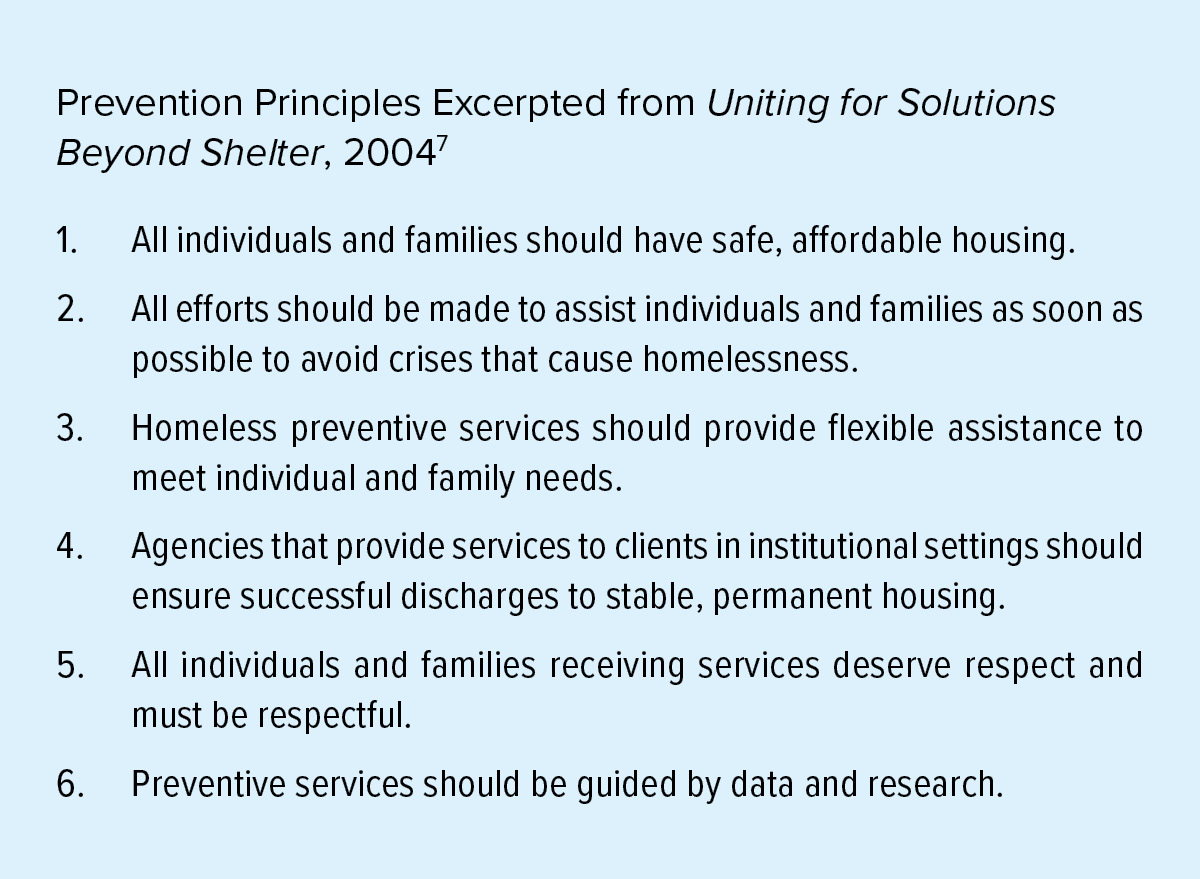

In the first half of 2004, Mayor Bloomberg’s administration released a five-year homelessness action plan titled Uniting for Solutions Beyond Shelter, with several principles guiding the prevention efforts outlined in the plan.7,8 The title alone demonstrates the Administration’s goal of lessening the City’s reliance on shelters and halting the continual expansion of the system. In fact, the action items listed as “next steps” in the plan included “reinvest savings [generated by the shift from shelter to prevention]” and “Close shelters to reinforce savings.” Overall, the plan set an ambitious goal of reducing homelessness by two-thirds in five years.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

Though Uniting for Solutions Beyond Shelter does not mention HomeBase by name, it refers to it as a pilot focusing on specific communities where services will be “delivered at a community level through neighborhood groups.”9

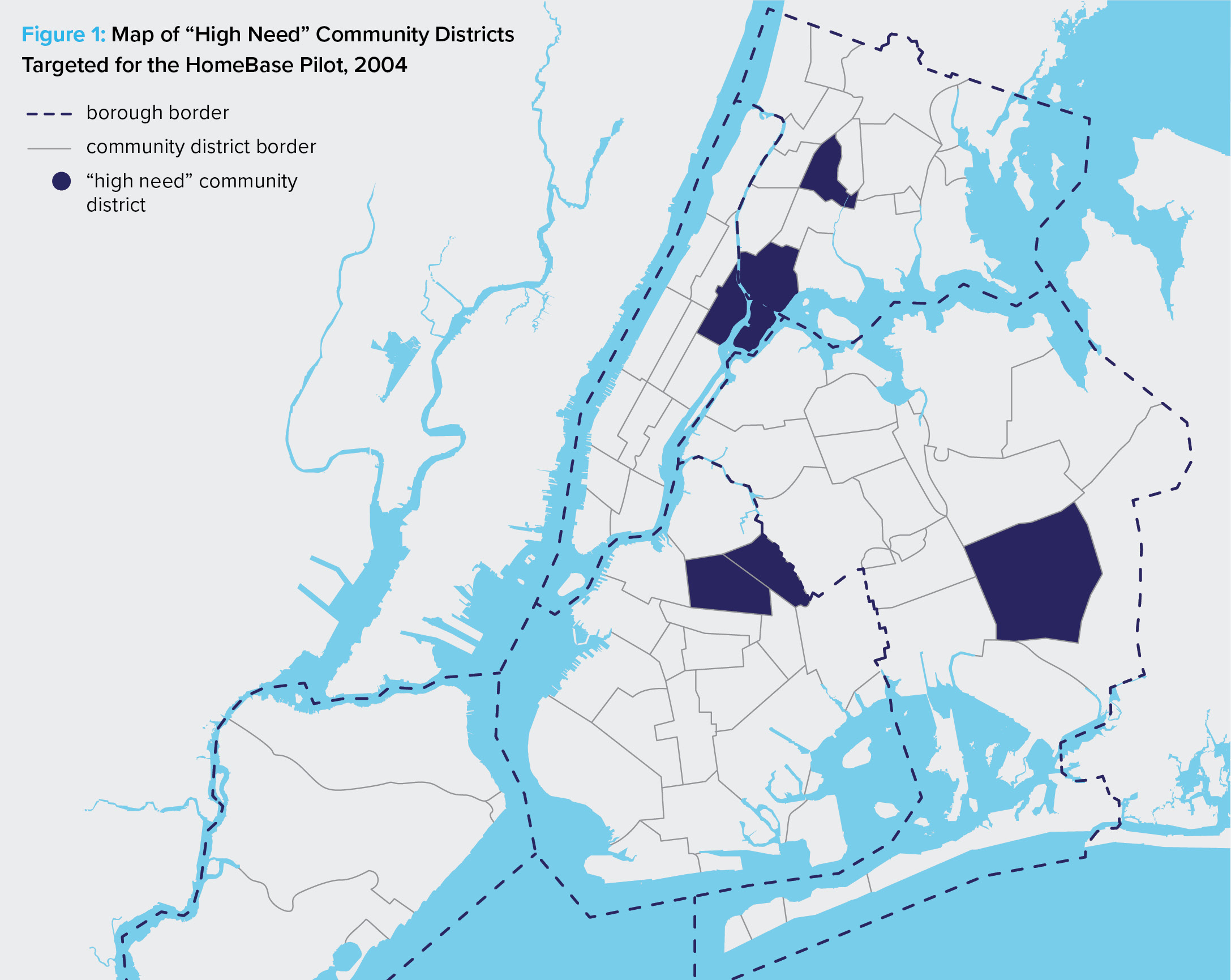

HomeBase’s pilot program was initially established in September 2004 in six community districts. These community districts were chosen based on their designation as “high need” as informed by an evaluation of a sample of shelter entrants’ last permanent addresses.10 The neighborhoods chosen were Bronx District 1 (South Bronx/Mott Haven), Bronx District 6 (East Tremont/Belmont), Brooklyn District 3 (Bedford-Stuyvesant), Brooklyn District 4 (Bushwick), Manhattan District 11 (East Harlem), and Queens District 12 (Jamaica/Hollis).11

Attempts to Reduce Homelessness through Voucher Programs

Concurrently, the Bloomberg Administration was experimenting with various rental subsidies to support families experiencing homelessness. In December 2004, the NYC DHS introduced the rental subsidy program known as Housing Stability Plus (HSP). The subsidy was intended to assist eligible families for five years, with the government contribution reduced by 20% each year in order to “encourage self-sufficiency.” However, subsidies were only available to recipients of cash assistance, which meant that families would lose their subsidy if they experienced any disruption to their cash assistance case. This voucher program, unfortunately, did not increase housing stability for families. In fact, the number of families who returned to shelter within a year of moving into permanent housing increased, rising from 0.8% in FY2005 (when it was introduced) to 4.2% in FY2008. New York City eliminated the program approximately three years after its introduction as it failed to keep families in their homes and out of shelter. In FY2007, the Administration created another voucher program, Work Advantage. This program sought to address the complexities faced by households who had previously resided in shelters by offering rental subsidies along with social support that encouraged “self-sufficiency” through work incentives.12 Work Advantage gave families more money than HSP, but expired after only two years and had an income limit that was low, meaning that a family ran the risk of losing the subsidy if a parent found a full-time job. In 2011, during Andrew Cuomo’s tenure as governor, New York State cut its portion of the funding for Work Advantage, forcing the City to eliminate the program.

Neither voucher program was able to stem the tide of families into New York City’s shelters. Unfortunately, the vouchers had short lifespans and the administration had misguided attempts at encouraging self-sufficiency—families were faced with the paradox of losing the voucher if their wages rose but were also unable to afford housing even with raised wages without the voucher benefit. Families would use vouchers for as long as they lasted, and many ended up back in the shelter system after the vouchers expired. Given these circumstances, HomeBase thus had the potential to become a critical program and lifeline for more families experiencing housing instability.

No Longer a Pilot: HomeBase’s Expansion and Funding

By 2008, HomeBase was no longer a pilot and had expanded operations from the six original community districts to community-based offices citywide. In 2008, new HomeBase contracts between DHS and partnering organizations began to stipulate that for a client to be considered “successful,” they should not enter shelter for a full 12 months after initially contacting HomeBase, a new baseline for measuring prevention outcomes in citywide reports.

At the start of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration in 2014, there were 14 HomeBase locations in New York City. As part of what it called a “holistic approach” to address the causes of homelessness, Mayor de Blasio’s administration prioritized expanding HomeBase to help families and individuals avoid entering shelter.13,14

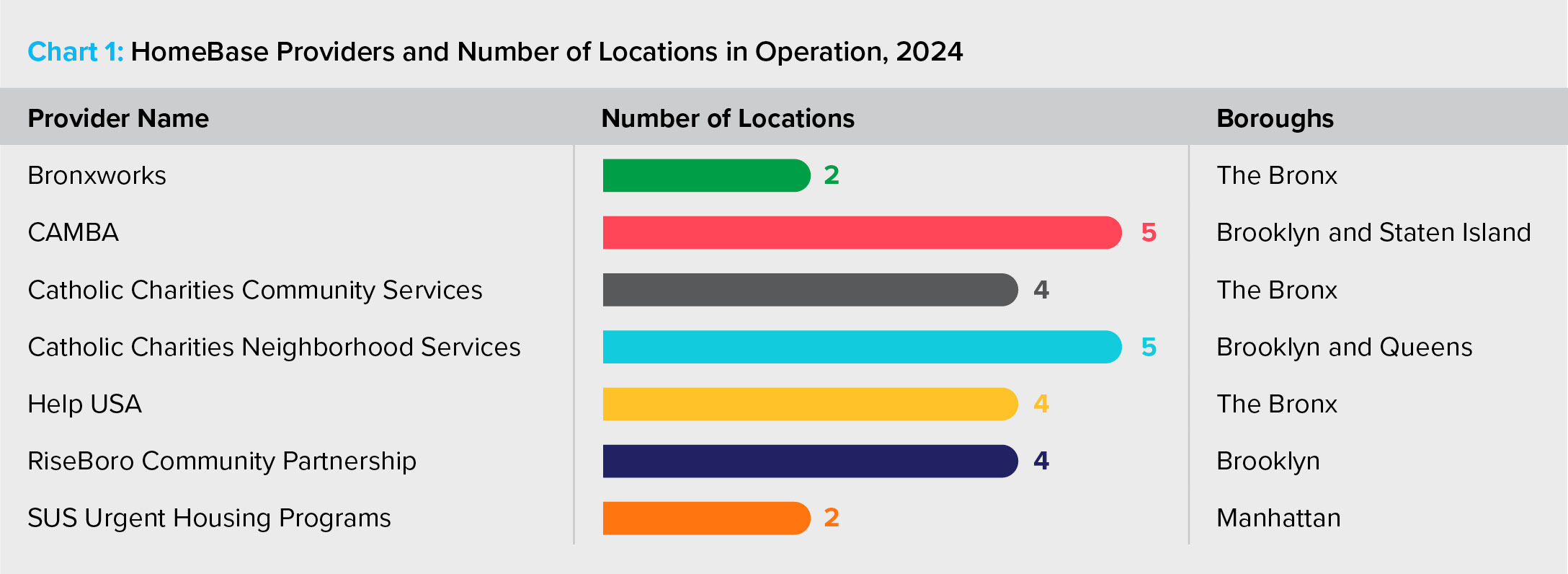

In 2016, Mayor de Blasio’s administration conducted a 90-day efficiency review of homeless service agencies and programs. As a result, the City announced several changes to its services, notably the creation of the Department of Social Services (DSS), which would now oversee HRA and DHS, as well as the integration of DHS’s HomeBase prevention unit with HRA’s Homelessness Prevention Administration.15,16 HRA, which administered many other prevention programs, such as the Rental Assistance Unit, would take over the management of HomeBase.17 The Department of Social Services and the City saw this integration as a way to reduce inefficiencies in homeless services, allowing for more seamless client support. It expanded HomeBase’s role as the first point of entry for those at risk of homelessness. HomeBase offices were based in a family’s community, so they would ideally not need to go to the centralized intake office to access services. The de Blasio Administration doubled its funding of HomeBase and, from FY2015 to FY2017, increased the number of locations from 14 to 23.18 As of 2023, there are 26 HomeBase locations operated by seven nonprofit providers.19 The Bronx and Brooklyn have the greatest number of locations, with each of these boroughs hosting ten HomeBase offices.20 The nonprofit organizations (see Chart 1) contract with the City to provide services within the local community.21

HomeBase and other prevention programs are funded via various federal and city funding streams, and the funding is budgeted across multiple units of appropriation within each fiscal year’s budget, making them difficult to track. In fact, the New York City Council has requested additional transparency from HomeBase’s related government agencies.22,23 Much of its funding comes from federal sources such as Temporary Aid to Needy Families program (TANF) and Emergency Solutions Grants (ESG) funds, though it is notable that the share of funding for NYC shelters coming from federal dollars has decreased every year since 2019.24

The operating budget for HomeBase has varied over the years but has generally shown an upward trend. This aligns with New York City’s efforts to reduce the rise in homelessness and keep families out of shelters. Fiscal Year 2018 saw the largest expenditure on HomeBase in the program’s history, when approximately $80 million (about $100 million in 2023 dollars) was spent. This was a proactive step toward fulfilling promises made by Mayor de Blasio during his two mayoral campaigns.

Defining Terms and Understanding the Landscape of Prevention

What Supports Currently Exist to Prevent Homelessness?

Depending on the challenge facing a family, they can access various New York City programs that seek to keep them in their homes and out of shelter. Many support services are available to residents through New York City’s HomeBase program. The City contracts with nonprofit service providers to operate HomeBase centers in communities. Local residents at risk of homelessness receive case management and support services, financial literacy education, employment assistance, and more. HomeBase is New York City’s main provider of both prevention services for residents on the brink of homelessness as well as aftercare services (see p. 9) for individuals and families exiting shelter. The community-based model is designed to help residents stay housed in their neighborhoods; residents must visit the HomeBase location that serves their zip code. HomeBase serves families with children, adult families, and single adults.

Below are some of the most common reasons a family might require assistance and the support available to them.

For families facing eviction:

Legal Assistance (Right to Counsel): Any tenant who qualifies based on income can access free legal representation in housing court or New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) administrative proceedings. Tenants do not have to have a formal lease. Tenants can connect with legal services organizations in person at their first court date or prior to it by calling 311 or contacting legal services organizations via phone or email. While having an attorney does not guarantee that an eviction will be prevented, it increases the likelihood that a tenant can remain housed. An analysis of 2019 eviction filings showed that 84% of tenants represented by a government-funded attorney were able to remain in their homes.25

For families with rental arrears:

One-Shot Deals: If a family has been unable to pay rent for some time and has built up rental arrears (or money owed on rent), they may be able to access a One-Shot Deal, through which the City covers their arrears and prevents eviction. Tenants do not have to have a formal lease. Financial assistance is also available to tenants who need help paying for utilities, assistance after a fire or disaster, and in other situations.26 One-Shot Deals are evaluated on a case-by-case basis and may be available to tenants not on the lease of the apartment in which they reside.27,28

For families in overcrowding situations who qualify:

City Fighting Homelessness and Eviction Prevention Supplement (CityFHEPS) vouchers through HomeBase: If a family is staying with another family in an overcrowded apartment and they are asked to find another place to stay, HomeBase can issue them a rental subsidy voucher that will cover a portion of their rent in a new apartment.

For families in conflict with their landlord or leaseholder:

Counseling/mediation through HomeBase: HomeBase offers mediation services to help resolve disputes between landlords and tenants and among tenants in a building or apartment. The goal is to maintain a tenant’s living situation and prevent them from needing to enter the shelter system.

How HomeBase Works: Entering the Office and Receiving Services

To access the services mentioned, clients must first make an appointment at their local HomeBase. They can locate their nearest HomeBase by calling 311 or visiting the HomeBase page on the Human Resources Administration (HRA) section of the New York City government’s website. Upon visiting their local HomeBase location, clients meet with a case manager to evaluate their needs, which are determined using a screening tool known as the Risk Assessment Questionnaire or RAQ. The RAQ asks clients for information related to demographics, employment, education, housing history, and current needs.29 The RAQ is scored between 0 to 25, with higher scores indicating a higher risk of homelessness. Case managers determine whether the case qualifies as preventative, to prevent homelessness from occurring, or rather as aftercare, to prevent a return to shelter.30 Clients who are seen for aftercare services are not required to meet a certain RAQ score to be eligible. Though this screening tool helps case managers determine what preventative cases may be taken on, case managers also have a certain level of autonomy to override determinations if they believe the client is at immediate risk of entering shelter if not for HomeBase services.

Clients determined not to be eligible for HomeBase services are pointed to resources that may address their needs but do not receive ongoing case management from the program. Eligible clients then work with a caseworker to develop a personalized plan to address their needs.31

Prevention versus Diversion

In New York City, the government has programs to both prevent and divert a family from entering the shelter system. Diversion and prevention employ similar tools—vouchers, case management, financial assistance, etc.—but occur at different points in a family’s journey. Like prevention, diversion efforts offer families resources to keep families out of the system. When a family visits DHS’s Prevention Assistance and Temporary Housing (PATH) intake center, the entry point for all families seeking shelter, and a PATH worker learns that they may have an alternate place to stay, the family may become a diversion case. Diversion cases are referred to HomeBase for additional assistance like counseling and other help. Often, families may be staying with someone else but have been asked to leave; in this case, HomeBase case workers connect with the family and whomever they may be able to stay with to offer cash incentives and, frequently, a voucher for the family to find a suitable apartment on their own.

Aftercare

What happens when a family exits shelter is another critical piece of the homelessness prevention puzzle. Known as aftercare, HomeBase is also tasked with providing families in the community with services like assistance with voucher renewals or help communicating with landlords. This critical work can keep families connected and on track to stability. However, aftercare is not compulsory, and services are provided to families who seek it out themselves, limiting the reach of this connection and support.

Aftercare, as offered by HomeBase, is an optional service for families exiting the DHS or HRA shelters using a voucher or rental subsidy. Voucher renewal is the most often used service offered through HomeBase’s aftercare. It is the periodic recertification process when families must contact HRA and submit paperwork to ensure the agency continues to make voucher payments to the landlord. HomeBase also offers many other services to clients to help keep them housed, as noted earlier in the report, including referrals to legal services in the event of an eviction filing and referrals to other support services in the community. HomeBase will also help clients understand their lease terms, communicate with their landlords, and help acclimate them to the neighborhood.

National Reception and Impact of HomeBase

HomeBase has significantly impacted the local and national homeless services landscape. It has been widely regarded as a model program for preventing homelessness, with other municipalities and the federal government looking to the program for inspiration in how to target their own services.32,33 For its exemplariness, HomeBase was a finalist for Harvard University’s Innovations in American Government award in 2006. In 2009, it won the HUD Secretary’s Opportunity and Empowerment Award, which honors programs that have resulted in benefits in employment, economic development, or housing choices for lower-income residents.34

During the Great Recession, beginning in 2008, the United States experienced a significant economic downturn due to the subprime mortgage crisis. As the worst financial crisis in the United States since the Great Depression of the 1930s, the Great Recession was marked by depressed wages, high unemployment, and inflated housing costs. This led to an increased number of families seeking financial assistance from the government, many of whom sought services for the first time. In response, in 2009, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), was signed, which included $1.5 billion in funding for the Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-housing Program (HPRP).35 HomeBase was influential in the development of HPRP. HomeBase was featured as a model program in a 2009 HPRP training series offered by HUD, which sought to help with regional implementations of prevention and rapid re-housing models.36 HPRP provided funding to implement services or financial assistance to prevent homelessness or help families and individuals be quickly re-housed.37,38 Households were eligible for HPRP funds if their incomes were below 50% of the Area Median Income (AMI).39 The funding for HPRP, administered by HUD, was granted to over 500 municipalities and is credited with doubling the resources available for homelessness prevention in most communities.40 New York City’s HomeBase program was the blueprint for how neighborhood-based prevention strategies could be deployed across the country. Later in 2009, the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act was amended and reauthorized as the Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing (HEARTH) Act, including significant changes to HUD’s assistance programs. Prevention resources were expanded in this reauthorization, and elements that made HomeBase’s approach a model when it was first piloted, such as using legal services and landlord mediation to keep people stably housed, made it into the legislation.41,42

Under the HEARTH Act, the definition of homelessness was expanded, which opened funding for preventive measures for people at risk of homelessness. It allowed programs to assist people who were not necessarily in the immediate throes of crisis, meaning that services could target community members who were experiencing housing instability more broadly. Grantees could now provide prevention and rehousing services like legal services or rental assistance to people at risk of homelessness.43 This allowed localities to undertake preventive measures that would help people avoid entering shelter altogether.

But Does It Work? Performance and Evaluations of HomeBase through the Years

Since its inception, HomeBase has been reported to be effective at keeping clients who receive their services from entering shelter. In its first year of operation, Mayor Bloomberg’s administration reported that 97% of all clients served at a HomeBase program (adults, adult families, and families with children combined) avoided shelter and remained housed. In the ensuing years, there were several academic studies of HomeBase. The Mayor’s Management Report also shares some limited data annually on HomeBase’s performance. Below, we will share what the publicly available data and studies tell us. Academic Evaluations

As HomeBase amassed praise and attention, DHS commissioned several studies to evaluate its effectiveness.44 Columbia University analyzed the first four years of the program (2004–2008) in a study, “Does Homelessness Prevention Work? Evidence from New York City’s HomeBase Program.” Researchers found that for every 100 families enrolled in HomeBase services, there were between ten and twenty fewer families entering shelter. They did not find any effect on the length of time spent in shelter.45 In 2008, DHS engaged Abt Associates and the City University of New York (CUNY) to conduct a study of HomeBase’s services and effectiveness. Researchers conducted a random assignment study with 400 families who sought help from HomeBase between June and August 2010. Half of the families received services, while the remaining 200 received the names of other agencies, such as HRA Job Centers, from which they could seek help.46 This randomized approach, which was designed to ensure impartiality and control of outside factors in scientific testing, was seen as a cruel misstep by the City to gather data on the effectiveness of its programming.47 Advocates for homeless families criticized the City’s treatment of the “control” group, who did not receive any support from HomeBase. The study was seen as an unnecessary risk to vulnerable families who were exposed to the possibility of entering shelter.48,49 Despite the controversy surrounding the study, its results highlighted the effectiveness of HomeBase for those who did receive services. Researchers found that families who interacted with HomeBase and ultimately entered shelter were able to spend over 20 fewer nights in shelter on average. It also cut in half the percentage of families who applied for shelter. The study also emphasized the cost savings of providing HomeBase services relative to housing families in shelters; savings offset costs by $140 per person.

Mayor’s Management Report Data

Produced annually, the Mayor’s Management Report (MMR) functions as the City’s report card. It details how the City served residents through its various programs and how the City is meeting its goals over time. Prevention services receive very little consideration in this report, with only two data points provided to help New Yorkers understand how effective its services are for families and individuals. For a program receiving millions of dollars in funding each year, and with mayoral administrations continually emphasizing the importance of prevention and diversion in their homelessness strategies, the dearth of information is glaring, an observation sharply noted by former NYC Comptroller Scott Stringer in January 2020 upon releasing an audit of the HomeBase program.50

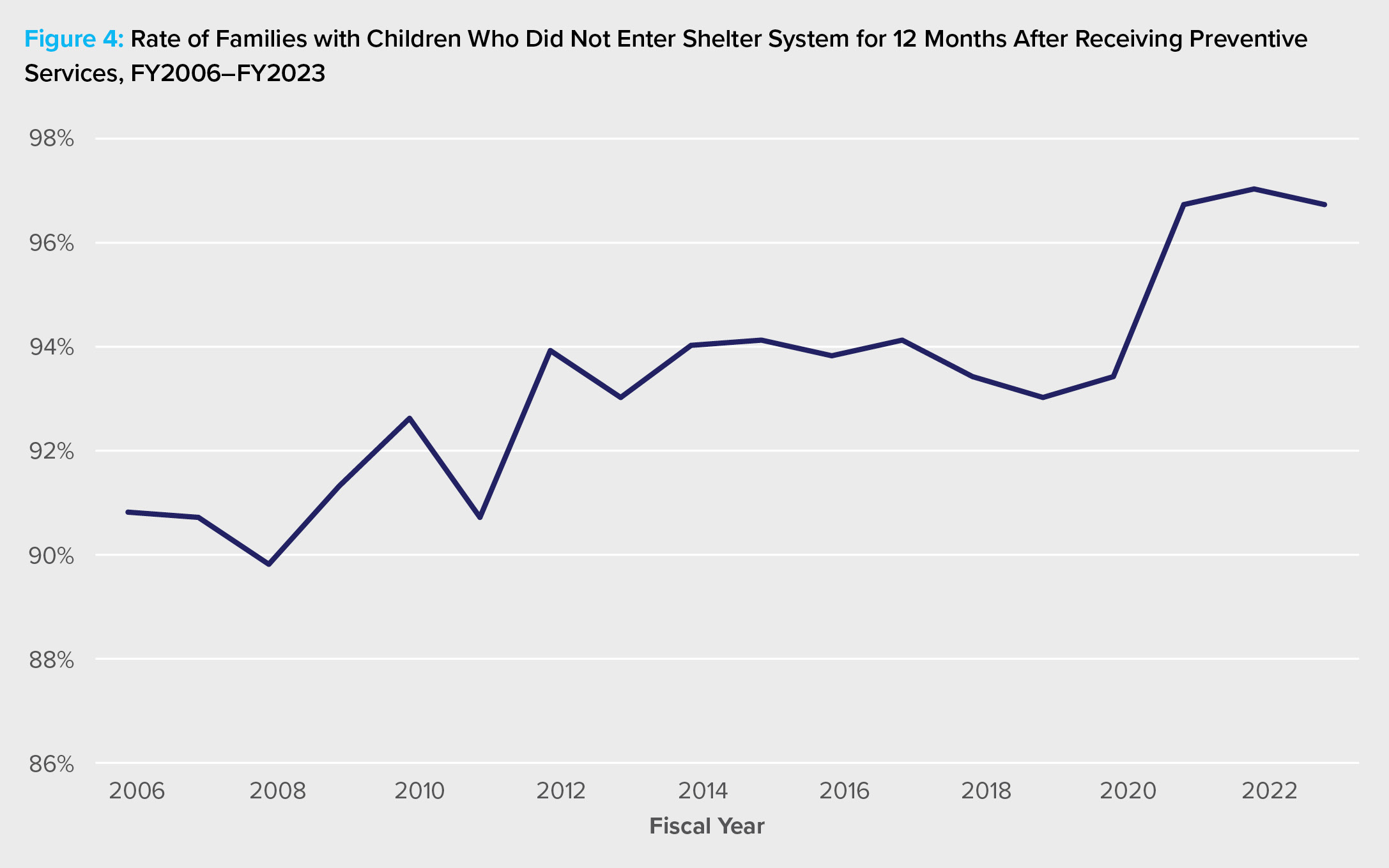

The first data point provided is the number of families with children receiving preventative services who did not enter the shelter system for 12 months following receipt of services. Overall, HomeBase has consistently maintained a prevention rate of around 90% or higher, trending positively over time but plateauing around 97% in recent fiscal years (see Figure 4). However, we do not know what share of families sought services but did not receive them. We also do not know anything else about the families—what type of services did they require? How long did HomeBase work with them? What communities need services more than others?

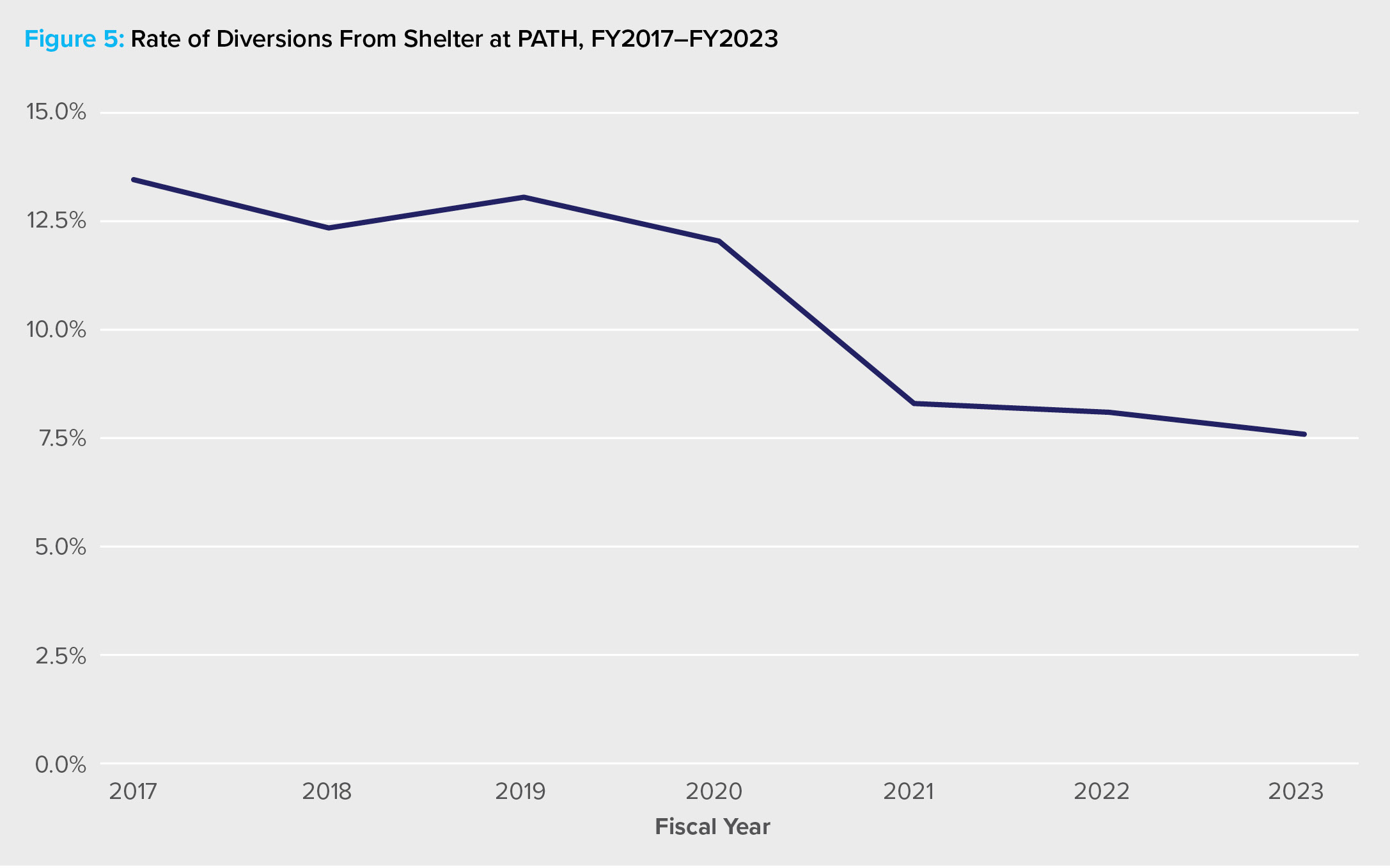

The second indicator is the percentage of clients successfully diverted at PATH from entering a homeless shelter. Prior to FY2017, the percent presented in the MMR included duplicates; thus, numbers pre-2017 and post-2017 cannot be compared. Overall, the number has declined in recent years, though it has consistently remained below 20% of all clients (see Figure 5). Again, we wonder what types of services these families used to prevent their entrance to shelter. How did the City manage to keep them housed? What tools are particularly helpful, and in which communities?

The Next 20 Years: More Transparency, More Families Stably Housed

Despite the dearth of publicly available data on how HomeBase functions citywide, we know that the services offered are of critical importance to the families and individuals they support. The functions of these community-based offices—negotiating with landlords, connecting tenants to legal services, providing housing vouchers, mediating among tenants—are not done by any other City entity with the same care and dedication. Anecdotally, we know that HomeBase’s model of neighborhood-centered advocacy and support is a lifeline for many families. With increasing pressure on the shelter system, a renewed focus on ensuring HomeBase is working is appropriate. Is the HomeBase model structurally sound for both the nonprofits providing services and the families in need of assistance? Is it meeting the needs of the communities it’s serving? According to Homeless Services United’s (HSU) City Council testimony from June 2023, there are significant challenges. HomeBases are strained, case managers are overwhelmed with cases, and staff turnover is high as a result. Demand for services continues to grow, but staffing is limited and wait times for families to receive services often exceed two months.51

It is unfortunate that the cornerstone of New York City’s homelessness prevention model is so overburdened and its challenges and successes poorly understood. With information like the above provided by the City on a consistent basis, a clear case could be presented for increased resources and support to neighborhoods experiencing high demand. In recognition of this, Council Member Erik Bottcher introduced a local law this past summer that would compel DSS to report annually on the outcomes and operations of HomeBase.52 This is an exciting opportunity for the City to once again use the information it has and collects to assess how to target services and, by extension, help families stay in their homes and communities.

What can the next 20 years of homelessness prevention look like for New York City and across the country? With homelessness increasing nationally, it is all the more urgent that we know what strategies work to keep families housed and how they can be replicated, expanded, and targeted.53 If here in New York City we had new and updated information from providers and families on the ground, the Big Apple could once again be a national pioneer and a leader in meeting families’ needs and helping them avoid shelter.

Glossary of Terms and Acronyms

Homelessness and Poverty

Aftercare – Programs and services that support individuals or families after they have exited shelter and moved into more permanent housing.

Cash Assistance – Financial assistance provided to families with children, single people, and adult families who are in financial need with limitations on its use.

Diversion – Programs and services that immediately help individuals or families who have just lost their housing to keep them from entering shelter.

HomeBase – New York City’s primary homelessness prevention program.

HomeBase providers – Nonprofit organizations that contract with New York City government agencies to deliver homelessness prevention services within their local communities.

Prevention – Programs and services to help keep individuals or families at imminent risk of homelessness from moving into a shelter or living in a place not meant for human habitation.

Rental subsidy – Ongoing financial assistance provided by a government-funded program that helps low-income households pay the rent on private rental units.

Government Agencies and Departments

NYC Department of Homeless Services (DHS) – New York City agency that works to prevent homelessness and provides short-term emergency shelter to individuals and families. The former administrator of the HomeBase program. Formerly operated as a stand-alone agency prior to coming under the management of the Department of Social Services (DSS), along with the Human Resources Administration (HRA).

NYC Department of Social Services (DSS) – New York City governmental agency that manages the Human Resources Administration (HRA) and the Department of Homeless Services (DHS).

NYC Human Resources Administration (HRA) – New York City agency that administers over a dozen social services programs. The current administrator of the HomeBase program. Currently managed by the Department of Social Services.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) – Federal agency that administers programs related to homeownership, affordable rentals, and homelessness.

Legislation and Funding

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) – Federal legislation signed in 2009. Created in response to the Great Recession of the late 2000s that, among other objectives, provided funds to HUD to promote stability in communities that the financial crisis had impacted.

Emergency Solutions Grant (ESG) – Federal grant program that provides funds to help people quickly regain stability in permanent housing after experiencing a housing crisis and/or homelessness; took effect in 2012.

Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-housing Program (HPRP) – Federal program created under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) that provided financial assistance and services to those at risk of homelessness or experiencing homelessness.

Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing (HEARTH) Act – Reauthorization of the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act passed in 2009 that made substantial changes to homeless assistance, including updating HUD’s definition of homelessness and increasing funding for prevention work.

McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act – Federal law passed in 1987 to support the identification, enrollment, and education of students experiencing homelessness.

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) – Federal program that provides states with funding for support programs for low-income families.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

The writing and research for this report was conducted through January 2024.

For additional copies or inquiries: Email INFO@ICPHusa.org or MEDIA@ICPHusa.org.