Suspensions are given to millions of students each year, taking them out of school and negatively impacting their behavior and achievement. Across the country, 2.8 million K–12 students received an out-of-school suspension in SY 2013–14. For students experiencing homelessness, removal from the classroom can have severe consequences, compounding the instability in their lives, contributing to missed class time, and taking away their access to school breakfast and lunch—often the only reliable food source they have.

Unfortunately, homeless students face a greater risk of being suspended. In Seattle, students who experienced homelessness received a suspension or expulsion at almost three times the rate of housed students in SY 2015–16. Even when it comes to the same type of offenses, the suspension rates for homeless students are often higher than for housed students. For the less-severe District Offenses given by Seattle Public Schools, 47% that went to homeless students resulted in a suspension. In contrast, 32% of District Offenses that went to housed students led to a suspension.

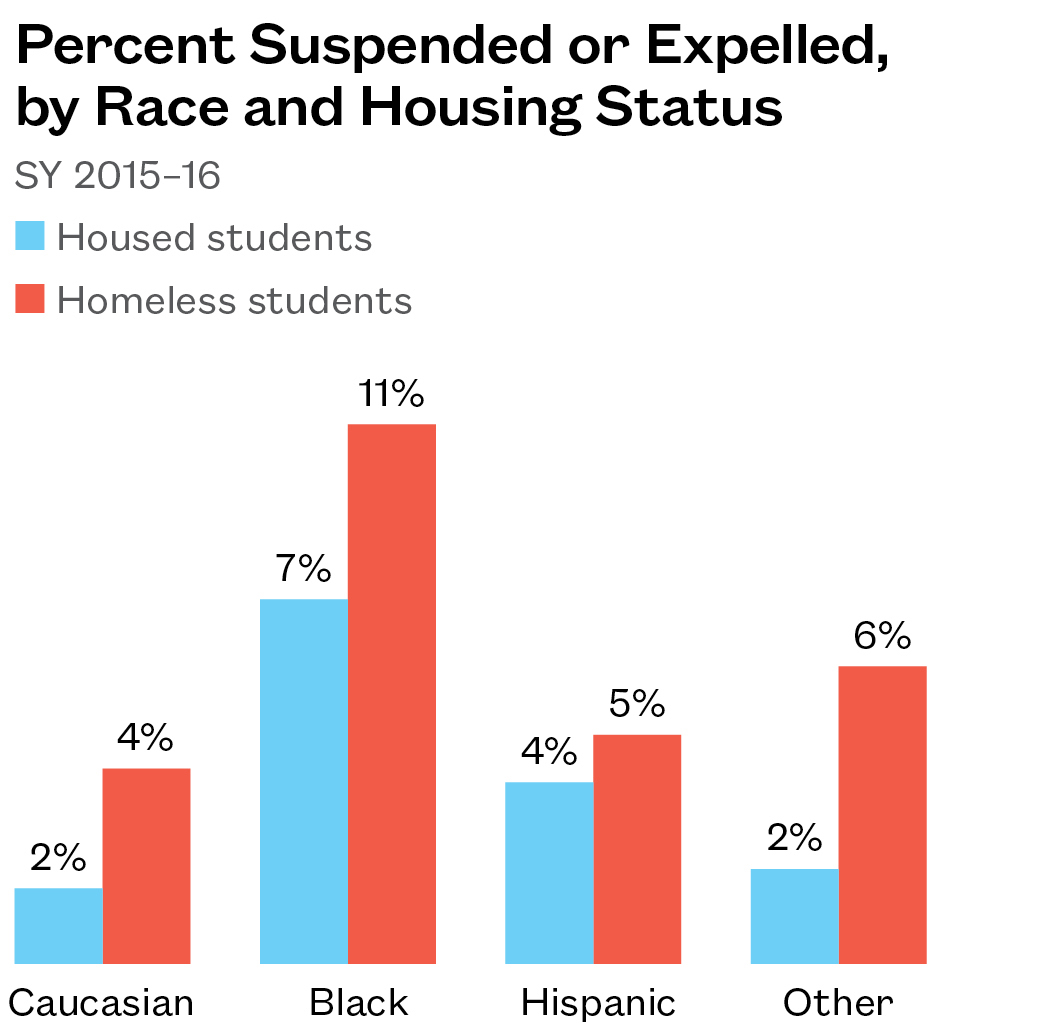

The gap in suspension rates grows even wider when race is considered. Seven percent of black students who were always housed in SY 2015–16 received a suspension or expulsion in that year, compared to 2% of white students who were always housed. For homeless students, the suspension/expulsion rate is 11% for black students and 4% for white students.

Why are homeless and black students receiving suspensions at higher rates than housed and white students?

For one, homeless students are much more likely to get inadequate amounts of sleep, which can leave them tired, irritable, or uncooperative at school. Other stressors, such as food insecurity, or living in a shelter or overcrowded residence, may also impact their behavior in school. For black students, long-standing racial inequities may cause their behavior to be judged more harshly than similar behavior by white students. Once students are viewed as having behavioral challenges, they can sometimes act in ways to reinforce those negative expectations.

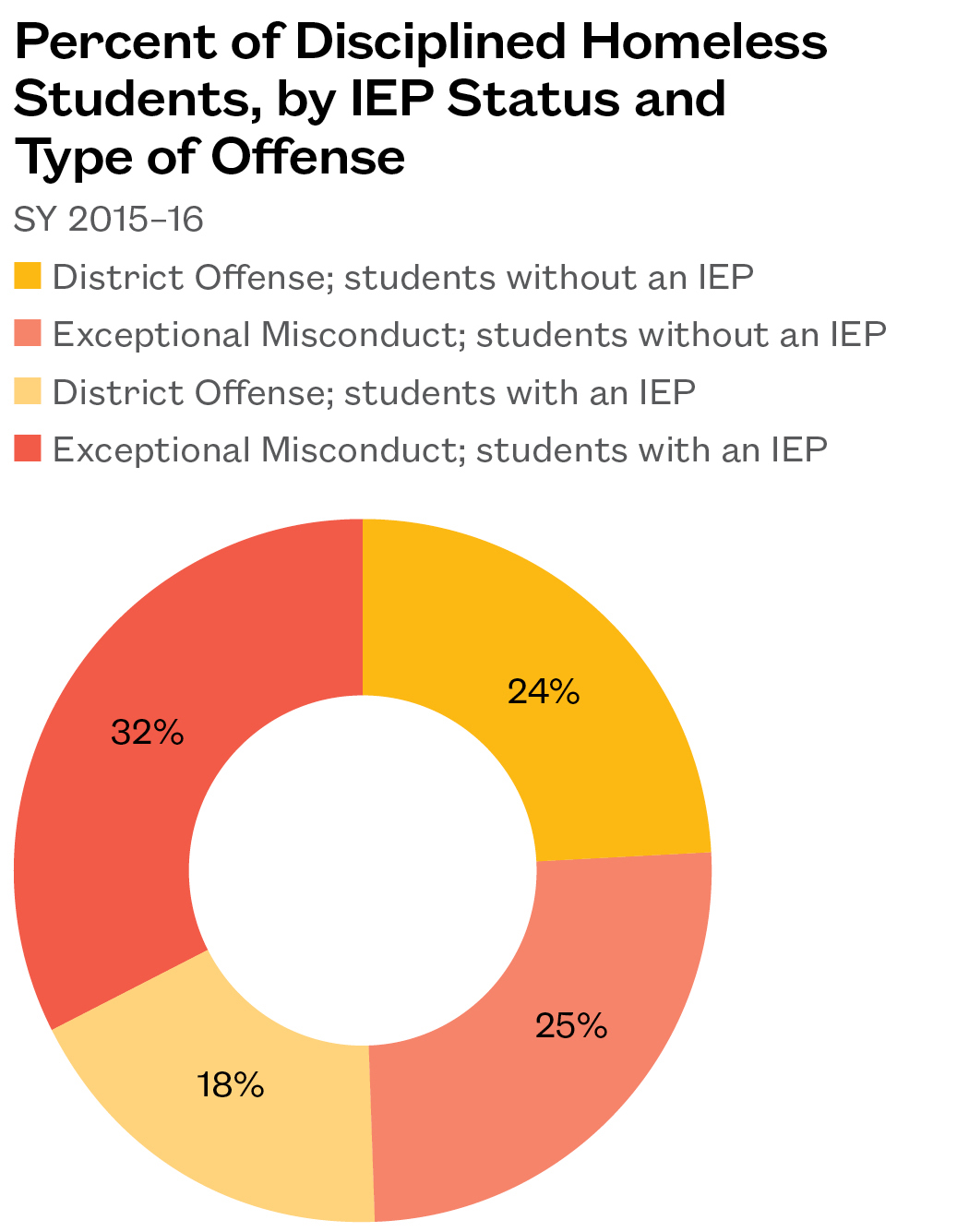

Homeless students with special needs also receive a high percentage of disciplinary infractions. Fifty percent of the disciplinary offenses that went to homeless students were given to students with special needs, although these students accounted for only 20% of the homeless student population. Exceptional Misconduct, the more severe type of offense, went to homeless students with an Individualized Education Plan (an indicator of special education needs) at a higher rate than for students without one.

Fortunately, many school districts are beginning to move away from suspensions and expulsions and are addressing racial inequities in discipline. In 2015, Seattle placed a moratorium on elementary school suspensions for certain low-level offenses while city leaders form a plan to reduce suspensions and ensure that they are applied evenly across the district. Seattle also convened a Race and Social Justice Community Roundtable, including 25 of Seattle’s public institutions and community organizations, to work together to address racial inequity in education. These initiatives are steps in the right direction to address behavioral issues with minimal disruption to students’ schooling and to narrow the suspension rate gap between different student groups.

Amanda Ragnauth, Policy Analyst