Across the country, children as young as 8 to 10 years old are experiencing homelessness. As a result, measurable gaps in their educational achievement can surface. In New York City, the elementary school outcomes of students living in shelters make a compelling case for providing additional supports to homeless students.

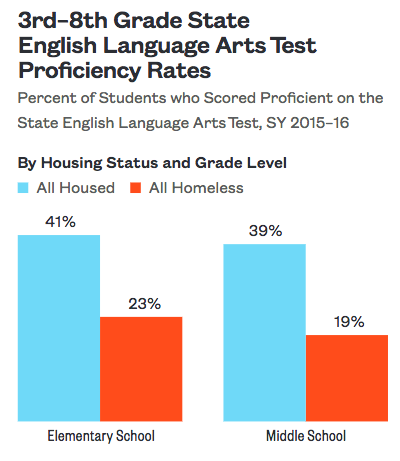

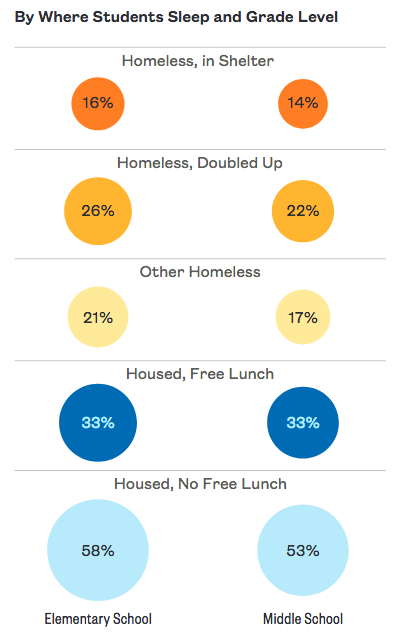

When looking at state assessment scores for elementary school students, we see that children living in shelters are more likely to fall behind. Less than one in five students living in shelter scored proficient citywide—half the rate of housed students who were low income and one-fourth the rate of housed students who were not low income. What’s more, this pattern persisted across the whole city—in all of New York City’s 32 public school districts, as well as the citywide special education district, students living in shelters scored lower on state math assessments than housed students of all income levels. Statistics like this leave many wondering, how can schools turn this troubling trend around?

Children living in homeless shelters face some of the most extreme educational challenges, since they often transfer schools mid-year and rack up many school absences. Even when they can remain in the same school, children who are homeless often have trouble getting assignments done at the shelter, don’t have Internet access where they are staying, or simply have trouble getting to school on time due to a long a commute. A social work director interviewed for our recent Atlas explained, “one middle school student [age 13] who was interviewed said that traveling from the Bronx to school in Brooklyn caused him to go from an A average in English to a 67% due to being late. His younger brother [age 8] really struggled to get up in time to get on the train for school, and he would often fall asleep in class. Last year, his teacher became concerned that he might have a sleep disorder because he was constantly nodding off. He missed out on a lot of valuable classroom instruction and he was moved to a special education classroom.”

When we see such large disparities in achievement rates, the important question becomes how can the individual needs of these children can be supported? How can policymakers and schools make sure that a history of housing instability does not determine a student’s future?

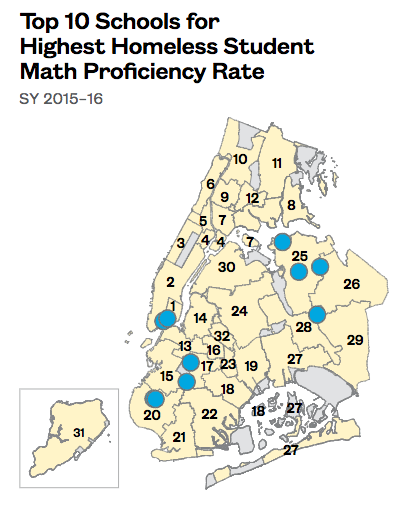

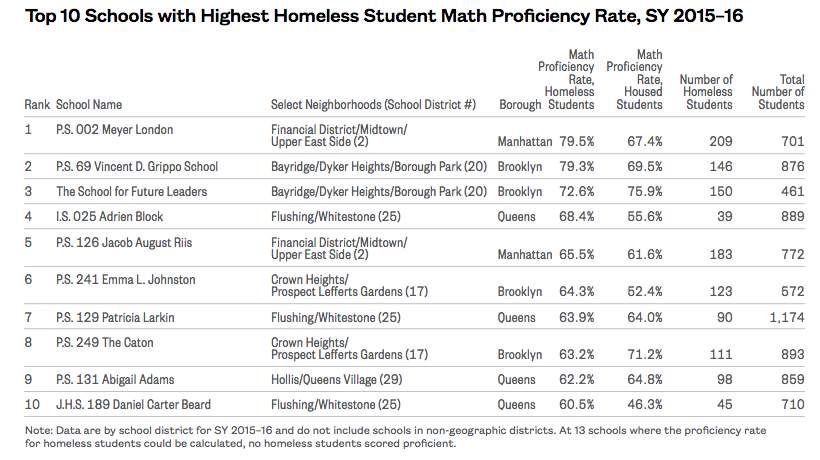

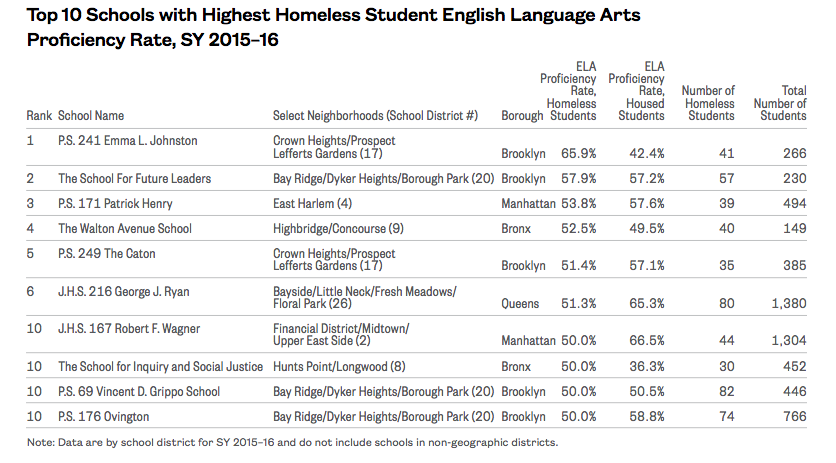

The City’s Department of Education has poured millions of dollars into initiatives to ensure that children living in shelters have an equal chance at succeeding in school. The successes of some schools citywide may help answer these questions about what supports are working and warrant replication.

In P.S. 53X Basheer Quisim Elementary School, located in the Bronx’s District 9, academic success prevails despite significant challenges. This elementary school is located in one of the highest-need school districts in the city and has consistently enrolled the largest number of students living in shelter of any school citywide. Still, students living in shelter scored proficient on their State math and English Language Arts (ELA) assessments at 34% and 36% respectively—roughly twice the citywide average for students in shelter and three times the Bronx average. To put that in context, the next ten elementary schools with the most sheltered students saw proficiency rates at just 16% for math and 15% for ELA, respectively, for these young students. (Additionally, P.S. 53X Basheer Quisim suspended just 0.2% of their students in SY 2015-16—the lowest homeless student suspension rate of any of the top ten schools with the most students living in shelter.)

Using data at the school level can help other educators consider how to replicate outcomes like those found in P.S.53X and other schools.

All schools have both the opportunity and the responsibility to support children living in temporary housing. School supports and staff can make a huge difference in the lives of these young students. We must ensure that children living in shelter have access to these necessary supports, no matter where they attend school.

Anna Shaw-Amoah, Principal Policy Analyst