After years of steady decline, suicide rates among high school students are on the rise, with suicide now ranking as the second-highest cause of death among adolescents aged 15–19. Adolescence is a transitional stage of life and the day-to-day challenges faced during this time can be overwhelming for many, placing them at heightened risk of depression, self-harm, and even suicide. These years can be particularly difficult for homeless high schoolers, who are also dealing with the many challenges that often accompany housing instability—anxiety related to not having a safe and permanent place to live; persistent sleep deprivation, hunger, dating and family violence; academic setbacks; and feelings of isolation—placing them at even greater mental health risk than their housed peers.

How Are Homeless High Schoolers Faring in NYC?

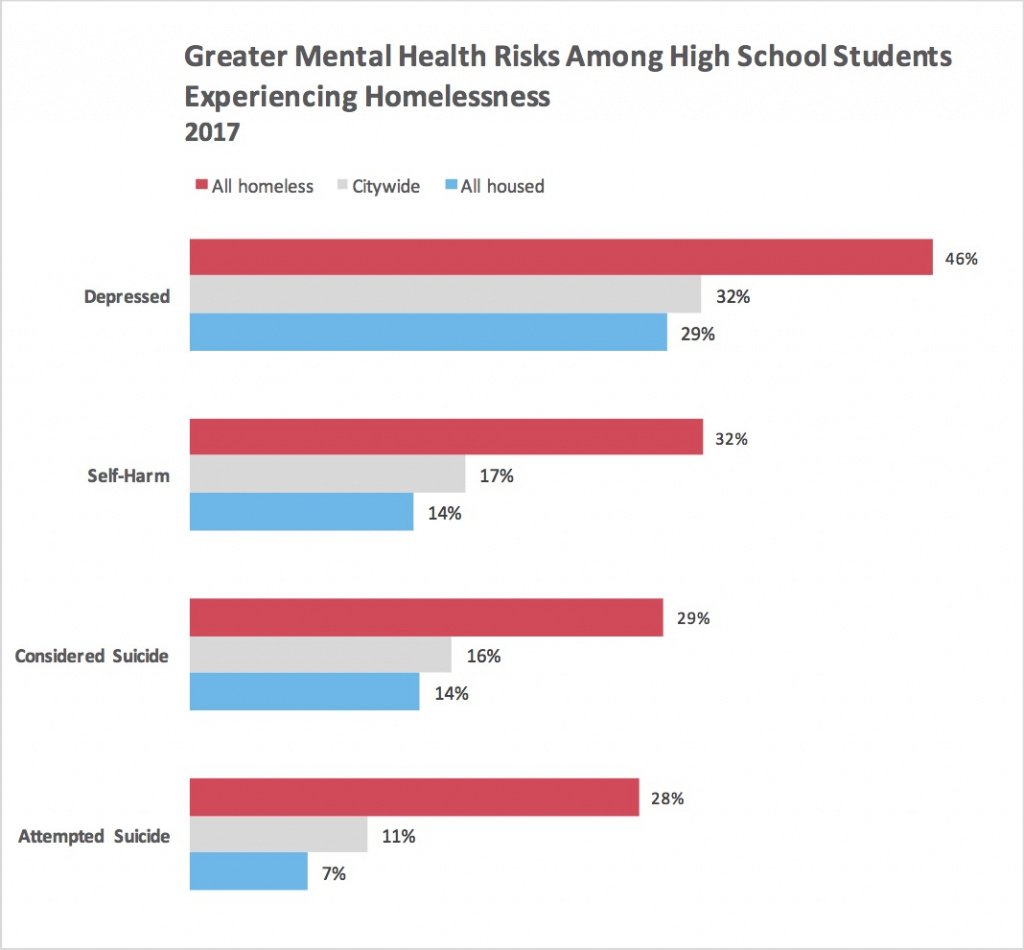

Depression is relatively common among teenagers, with one-third of New York City high school students reporting feeling depressed. However, the prevalence of depression among students who identified themselves as homeless is significantly higher, with nearly half reporting struggling with depression.

A shocking number of high school students report inflicting self-harm, and many have considered or even attempted suicide. Overall, close to one in six high school students reported purposefully hurting themselves (17%) or considering suicide (16%), and one in 10 reported attempting suicide (11%). While these numbers are serious enough, an alarming one in three high school students experiencing homelessness reported inflicting self-harm (32%), twice the rate of their housed peers. An almost equal share reported considering suicide (29%) or attempting suicide (28%)—between two and four times the rate of their housed peers.

The severity of these mental health risks varies by where homeless students sleep. In New York City, the majority of homeless high schoolers (58%) live doubled-up in overcrowded, often substandard living conditions. An additional 32% of homeless high schoolers live in shelters, with the remainder either paying out-of-pocket to stay in short-stay motels, or living unsheltered in places not meant for human habitation.

Homeless teenagers living in shelter face the gravest mental health challenges. Feeling isolated and demoralized, as many as two out of every five sheltered high school students reported purposefully hurting themselves (41%), and half reported that they attempted suicide (50%).

Do Homeless High School Students Seek Mental Health Support?

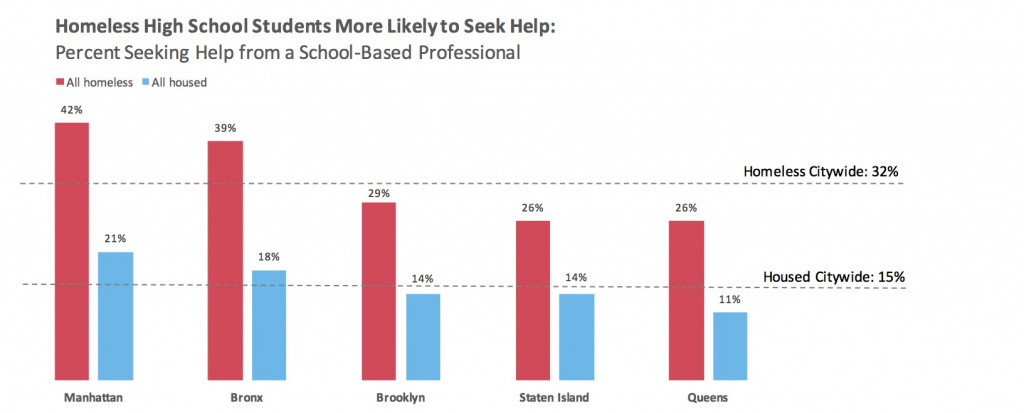

Despite these sobering numbers, when availed of the opportunity, homeless students seek help. In fact, high schoolers who experience homelessness are twice as likely as their housed classmates to report receiving help for an emotional or personal issue from a professional at school (32% vs. 15%). This trend stands across all five boroughs, and helps to illustrate the important role that schools can play in supporting the needs of homeless students. Some schools have counselors, social workers, and therapists who are available to help students through their mental health challenges. Others have School-Based Health Centers (SBHCs), which provide students with primary health care and mental health services either on site or by referral.

While SBHCs can help students with underlying mental health issues or other obstacles they face as a result of housing instability, access is limited. Only 46% of the city’s homeless high schoolers attend a school with a SBHC. In Brooklyn and Queens these percentages are even lower—only about one in every four homeless students in Brooklyn and Queens attended a high school with a SBHC (23% and 26%).

Aside from SBHCs, there are few services available to homeless high school students experiencing mental health challenges. One important exception is high schoolers in Districts 7 and 23 (Mott Haven and Brownsville). Through the Single Shepherd initiative, every 6th–12th grade student in these two districts is paired with a social worker who advocates on their behalf and counsels them through social-emotional challenges and the transition from high school to college. While this initiative benefits homeless high schoolers in these two districts, it is very limited in scope. Also limited in its capacity is the Department of Education’s Bridging the Gap program, which provides homeless students with assigned social workers and community coordinators to assist them in a variety of ways, including helping families access resources and directly counseling students. This program prioritizes staff assignments to schools with high rates of student homelessness, as limited staffing and funding prevent Bridging the Gap from providing support to all students in need. Both coverage of and access to mental health services is a continuing issue for high school students experiencing homelessness.

Why the First Step to Addressing Mental Health Challenges is Identifying Them

The mental health challenges experienced by homeless high schoolers exacerbate some of the educational challenges already prevalent among homeless students, such as chronic absenteeism, academic setbacks, and lower graduation rates. When homeless teens experience depression, it can prevent them from forming healthy social bonds and drive them to risky behaviors like drinking and drug use, putting their physical and emotional health in danger.

Available self-reported data offer some initial insight into the prevalence of mental health challenges among homeless high school students and highlight the urgency of increasing access to supports. In order to increase this access, the first step is to identify the prevalence of mental health risk factors among high school students both at the district and school level. Furthermore, to effectively address the mental health needs of homeless students, more needs to be known about how their experiences with housing and economic instability affect their school attendance and academic performance. Also, while existing initiatives are a step in the right direction, access must become more universal. Identifying homeless high schoolers, understanding their unique mental health challenges, and increasing access to the appropriate support services are all needed in order for these students to have an opportunity to succeed both in and beyond high school. More pointedly, increasing homeless high schoolers’ access to mental health supports could quite literally save their lives.