May 2018

Homeless high school students face challenges accessing health care, especially for chronic conditions like asthma. These teens face obstacles in their day-to-day lives: they often do not know where they are going to sleep and face hunger, abuse, and violent situations. Too often, their healthcare is placed on the backburner. Yet these are the very students who need consistent care the most. Available data indicate that homeless students are up to twice as likely to have asthma than housed students. Immediate solutions are needed to make sure that homeless students can be properly diagnosed and have the resource to manage their conditions. Meeting the health needs of homeless students is a key factor in ensuring that they attend school regularly, are able to learn, and ultimately graduate from high school.

Key Findings

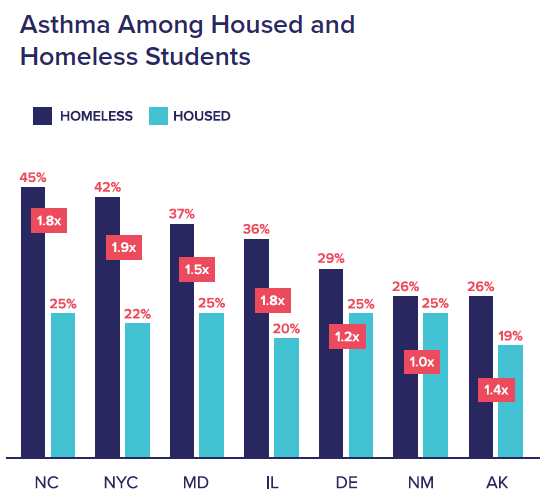

- Homeless students are more likely to have asthma than their housed peers. In North Carolina and New York City, homeless students had twice the asthma prevalence rate of housed students (45% to 25% in North Carolina and 42% to 22% in New York City). The CDC reports that overall, in the United States 18% of teenagers reported that they had ever had asthma.*

- Homeless students were three times as likely as their housed classmates to be unsure of whether they had asthma.

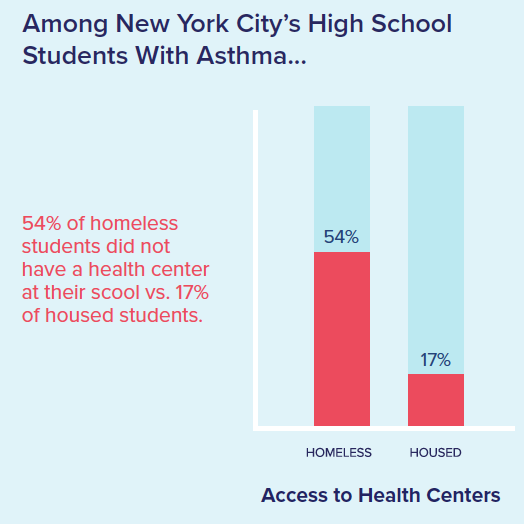

- Among students with asthma, homeless students are less likely to have a school health center than their housed classmates. Of homeless students with asthma in New York City, 54% did not have a school-based health center, while 17% of housed students with asthma reported not having one.

Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS)

Data from this brief are derived from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Youth Risk Behavior Survey. The CDC and its partners in state and local health and education agencies are on the front line of collecting data to understand the risks faced by homeless high school students across the country. The national Youth Risk Behavior Survey monitors priority health risk behaviors that contribute to the leading health and social issues in the United States. In 2015, 8 states and a handful of cities asked students about their housing status. The subsequent 2017 survey collected data from 19 states. Any state and city may proactively collect information from students experiencing homelessness in their schools by simply electing to add the CDC’s standard housing question to the YRBS. For more information, contact the CDC or your local YRBS partner agency.

*Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Health Statistics Tables for U.S. Children: National Health Interview Survey, 2016, table C-1, https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/NHIS/SHS/2016_SHS_Table_C-1.pdf.

Note: Data are representative of high school students from 2014–15 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) data in Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Mexico, North Carolina, and New York City. Not all surveys asked the same questions, so data are shown where available. For more information and data notes, visit https://www.icphusa.org/homelessstudenthealth/.

Asthma More Common Among Homeless Students

- Homeless students report a higher prevalence of asthma than their housed peers. The largest gap in asthma prevalence was in both North Carolina (45% to 25%) and New York City (42% to 22%), where homeless students had almost twice the prevalence rate.

- Reported asthma rates for homeless students ranged from a high of 45% in North Carolina to a low of 26% in New Mexico and Alaska. Meanwhile, rates for housed students were relatively consistent, ranging between 19% and 25%. This suggests that poor housing and environmental factors, coupled with irregular healthcare access, are disproportionately affecting homeless students.

Homeless students had

nearly 2x the asthma rate

of housed students in NYC.

Among Homeless Students, Blacks and Hispanics Report Highest Asthma Prevalence

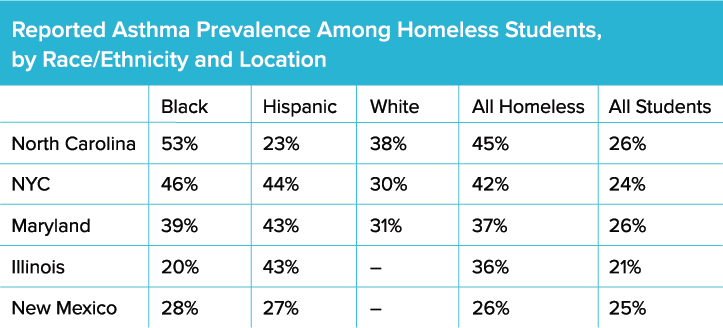

- Overall, 39% of homeless high school students reported asthma compared to 23% of housed students.

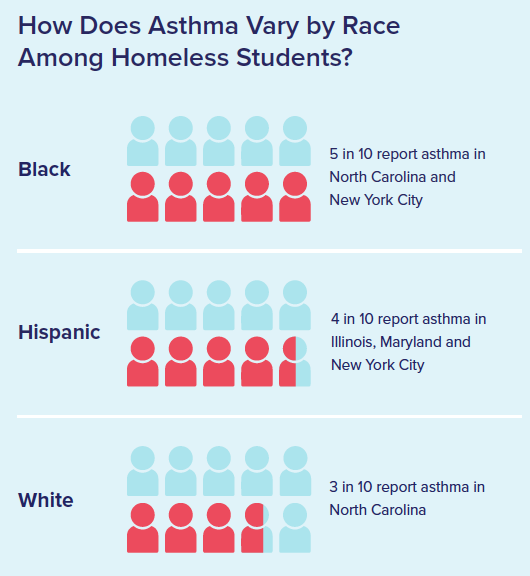

- Approximately half of all black homeless students had asthma in North Carolina and New York City.

- More than 40% of Hispanic homeless students had asthma in Maryland and New York City.

- The highest asthma rate among white homeless students was 38% in North Carolina.

- Homeless students report higher rates of asthma compared with their housed classmates across all racial/ethnic groups and locations.

“It took a really long time to be diagnosed.

We were moving around. I kept going to the

emergency room.…Everybody just thought

I was skipping school.”

—Formerly Homeless High School Graduate,

Class of 2016, New York City

Homeless Students Face Difficulties Being Diagnosed

- Greater than the disparity in reported asthma prevalence between homeless and housed students, even more severe is the disparity in students who were unsure whether they had asthma (10% to 3%). A proper diagnosis is the first step to managing and treating a chronic health condition such as asthma, and ensuring that the student stays in school.

Homeless high school students are 3x as likely

to be unsure of asthma diagnosis

as housed students.

Homeless Students Need School-Based Medical Supports

- Homeless students with asthma in New York City were over three times less likely to attend a high school with a health center. More than half (54%) did not have a health center, compared to only 17% of housed students with asthma.

- School-based supports reduce the risk of asthma attacks among students and ensure that in the case of an asthma attack, students do not miss the rest of the school day due to an emergency room visit. Medical support located in the school building takes away some of the anxiety that students may feel from having to use their inhaler and manage their asthma alone.

What Steps Should Be Taken?

Lowering barriers to medical care for homeless students is critical. Discussion with school nurses in New York City public schools* has revealed that if a student comes to the nurse’s office or school health center with even a minor health concern like a headache, they cannot receive care if a medical authorization form has not been signed. For students with asthma who use an inhaler or are at risk of an asthma attack, they may not be able to receive medical services at school, which can result in a costly emergency room visit and time away from the classroom. Among students who are already at risk for chronic absenteeism, this means that their medical conditions are an additional barrier to academic success. At a minimum, health centers should conduct outreach with shelters, families, and school liaisons to ensure that the importance of parental consent forms is clarified for parents and guardians.

A more comprehensive approach is needed to to truly increase access to healthcare among this group, the DOE and partners must prioritize health centers in schools with high numbers of homeless students, allot sufficient funding, and train health staff in the rights of students experiencing homelessness or living apart from their parents and in trauma-informed care practices.

*ICPH spoke with NYC Department of Education nurses during their annual training in Fall 2017.

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, President and CEO

Aurora Zepeda, Chief Operating Officer

Katie Linek Puello, Digital Communications Manager

Project Team:

Anna Shaw-Amoah, Principal Policy Analyst

Amanda Ragnauth, Policy Analyst

Kaitlin Greer, Policy Analyst

Rachel Barth, Policy Analyst

Marcela Szwarc, Graphic Designer