Nearly four years after communities across the country began implementing rapid-rehousing programs on a large scale, the approach has gained a reputation as the best available strategy for solving homelessness. Yet the understanding of how programs are structured, whom they serve best, and which local characteristics are important for their success is limited because programs vary so widely from community to community. Consideration of these factors is key to crafting cost-effective programs that address homelessness and promote household stability. This brief presents a case study of Philadelphia’s experience with rapidly rehousing its homeless population between 2010 and 2012. It highlights the role of data collection and analysis in effectively using rapid-rehousing programs as part of a larger, comprehensive homeless-services effort.

The City of Philadelphia

More than one in four Philadelphians lives below the federal poverty threshold (between $11,670 for a single adult and $23,850 for a family of four), making Philadelphia the poorest city in the United States with a population over one million. Although Philadelphia has a reasonably affordable housing market—the median monthly housing cost for renters is $876, and fair market rent for a two-bedroom apartment is $1,075— 57% of Philadelphia households spend at least 30% of their income on rental and other housing expenses.1

Homelessness in Philadelphia

Philadelphia’s Office of Supportive Housing (OSH) coordinates the city’s homelessness system, serving 18,743 people, 46% of whom lived in families in 2011. OSH manages two separate in-take centers (one for families and single females and another for single men) and during the height of HPRP implementation coordinated 6,103 emergency, transitional, and Safe Haven beds, 1,352 rapid-rehousing beds, and 4,732 permanent supportive housing beds. At intake, OSH case managers place households in emergency shelter if space is available. If the system is at capacity, households must find other places to stay until beds become available. Once clients are admitted to shelter, they are screened and referred to all appropriate programs, including transitional housing, rapid rehousing, and permanent supportive housing. Clients who are turned away from emergency shelter due to space constraints are still eligible for other housing-assistance programs. OSH also coordinates with the Philadelphia Housing Authority, which annually sets aside a combination of public housing units and Section 8 housing choice vouchers for 300 homeless families and 200 single adults.2

Philadelphia’s Approach to Rapid Rehousing

Philadelphia’s rapid-rehousing program began with a one-time Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Rehousing Program (HPRP) grant in 2009 of $21.5 million, about half of which, $11.2 million, was used for rapid rehousing. To qualify for rapid-rehousing assistance, clients had to currently reside in emergency or transitional housing and could not have significant behavioral health issues that could be managed more effectively by other programs. To receive prevention aid, clients had to be imminently at risk of homelessness and in need of temporary financial assistance to stabilize existing housing. HPRP funds for both prevention and rapid rehousing could cover costs associated with housing search and placement and provide limited case management relating to housing stability, legal services, credit repair, and/or outreach. Local housing and homeless-service providers in Philadelphia disbursed funds to cover up to 18 months of rental assistance; missed rent payments; security and utility deposits; utility payments; moving costs; and motel and hotel vouchers for homeless and at-risk households who earned 50% or less of the area median household cash income. Throughout implementation of the program, OSH officials collected and analyzed data, evaluated outcomes, and changed eligibility guidelines and program procedures to better target prevention dollars to households most likely to become homeless and rapid-rehousing assistance funds to those already homeless and most likely to maintain stable housing after assistance ended.3

Refine, Target, Stabilize

Federal HPRP guidelines allowed communities to disburse funds to households making below 50% of the area median income, which amounts to between $27,075 (for a single adult) and $45,100 (for a household of six) in Philadelphia. After the first year of implementation, OSH targeted a larger portion of the HPRP grant to rapid rehousing and less to prevention assistance, also changing the program-eligibility requirements to ensure that they were reaching households most in need yet also most able to maintain housing. Using demographic data, OSH began targeting rapid-rehousing assistance to households earning between 20% and 30% of the area median income (between $10,900 and $16,350 for a single adult and between $18,040 and $27,100 for a family of six), as opposed to the previously allowed 50% and below, and requiring eviction notices from those receiving prevention aid. OSH realized that Philadelphia households under 20% had too little income to remain stably housed after temporary subsidies ended and that those above 30% would more likely be able to maintain housing even without temporary subsidies.4

With these new guidelines in mind, case managers at emergency or transitional-housing facilities screened clients for rapid-rehousing program eligibility and forwarded applications to OSH for decisions about enrollment. Once applications were approved, each provider found housing options for clients through its own network of landlords, accompanied clients to a maximum of three apartment visits, and helped to negotiate lease terms. The process took roughly 60 days from referral to lease date. To incentivize landlords and provide stability to rapidly rehoused tenants, OSH disbursed aid for a minimum of 12 months, with tenants contributing 30% of household income toward rent. Housing providers were instructed to work with clients to find homes whose rents would not be more than 50% of current household income, as OSH found that households paying more than that were more likely to return to shelter.5

Results Over Time

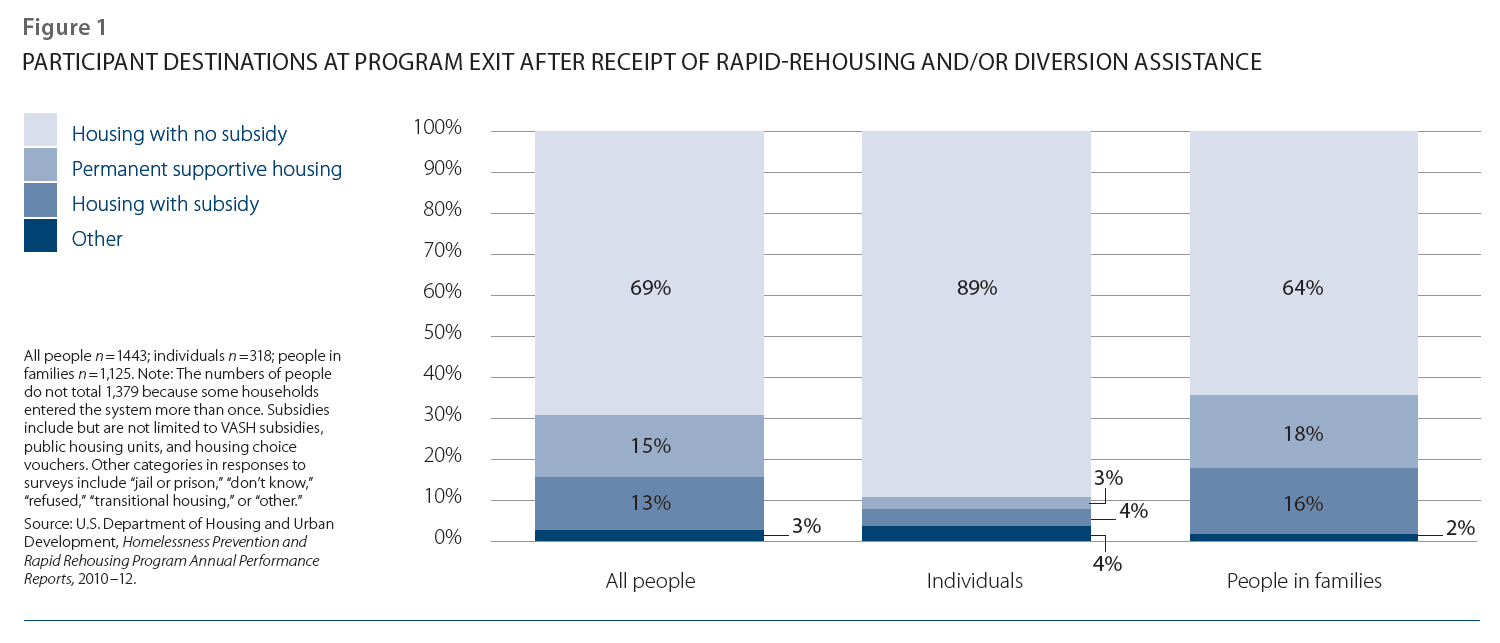

By the end of the grant period, Philadelphia had provided 4,286 households with prevention services and 1,379 households with an average of $6,000 in rapid-rehousing assistance; some households received both. Median monthly household income at entry was between $501 and $750, and in FY2011 13% of all homeless people in the city, at most, received rapid-rehousing assistance. Figure 1 shows the results for those clients who received rapid-rehousing assistance. Over the grant period, more than two-thirds (69%) of all people—individuals and families—exited the program to permanent housing without any ongoing subsidies, covering rent on their own; 15% moved to permanent supportive housing; and 13% left the program for permanent housing with some other ongoing subsidy, such as public housing, Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing (VASH) subsidies, or housing choice vouchers.6

When differences between families and individuals were explored, a much higher percentage of families than singles were found to have exited to permanent supportive housing (18% vs. 3%) or exited the program with some other ongoing housing subsidy (16% vs. 4%). For the 34% of families who exited into either permanent supportive housing (18%) or housing with subsidies (16%), assistance was used primarily to tide over households in shelter or other temporary housing who were awaiting placement into long-term programs such as supportive housing, public housing units, or housing choice vouchers. The remaining two-thirds of families exited to permanent housing without further rental assistance. In addition, almost nine out of ten single adults (89%) who participated in the program exited without further subsidies.

What is unknown for both individuals and families who exited without subsidies is whether the assistance was sufficient to stabilize households or if additional funds were needed but unavailable. On one hand, the high percentage in both groups who did not receive subsidies could reflect the efficiency with which the program was targeted to households that had specific income ranges and were in housing that was affordable to them at their current, rather than expected, income levels. On the other hand, the disparity between the proportion of single households exiting to housing without subsidies and that of families doing so may also reflect the different barriers facing each group. Affordable housing may be easier to find for one person than for a family of two or three. Families must also shoulder additional expenses for child care, clothing, food, transportation, and other necessities for children. Only more detailed and longer-term data that distinguishes between families and individuals can answer the many remaining questions about the effectiveness of the program; nevertheless, the availability of affordable housing and the existence of longer-term housing subsidies in Philadelphia are worth noting in the overall evaluation of the program.

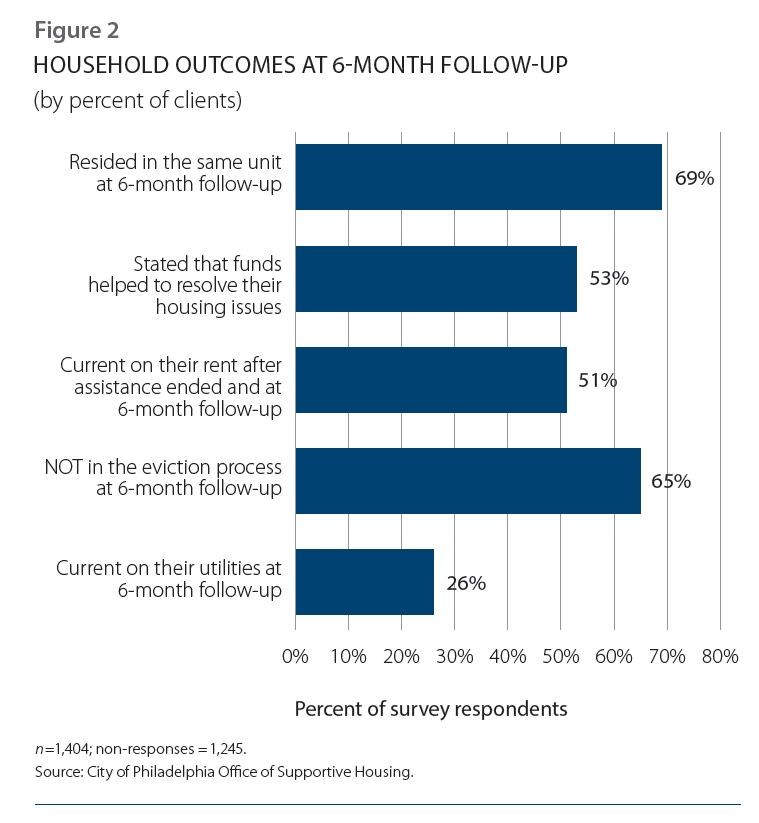

As part of its ongoing efforts to evaluate and improve its housing and homeless services, OSH commissioned an analysis and found that 13.6% of households who received rapid-rehousing assistance between October 2009 and July 2013 returned to shelter, compared with 39% in a matched comparison group (a comparison between individuals and families is unavailable). A separate survey of clients six months after program exit found that 69% of respondents were still residing in the same units they had occupied when they exited the program, 51% were current on their rent, and 65% were not in the eviction process (see Figure 2). These results raise concerns, as half (49%) of the households are not current on their rent at the six-month mark, 35% are in the eviction process, and only one-quarter are keeping up with their utility bills. While only half of the surveys sent out (47%) were returned and the proportion of respondents who received prevention funds as opposed to rapid-rehousing assistance is unclear, the survey shows some of the strongest data to date about the utility of targeting rapid-rehousing aid to households who have income. Still, neither distinguishes between families and single-adult households, nor does either present housing outcomes after 12 and 24 months. Without longer-term, household-specific data, these studies are of limited utility in understanding program impacts.7

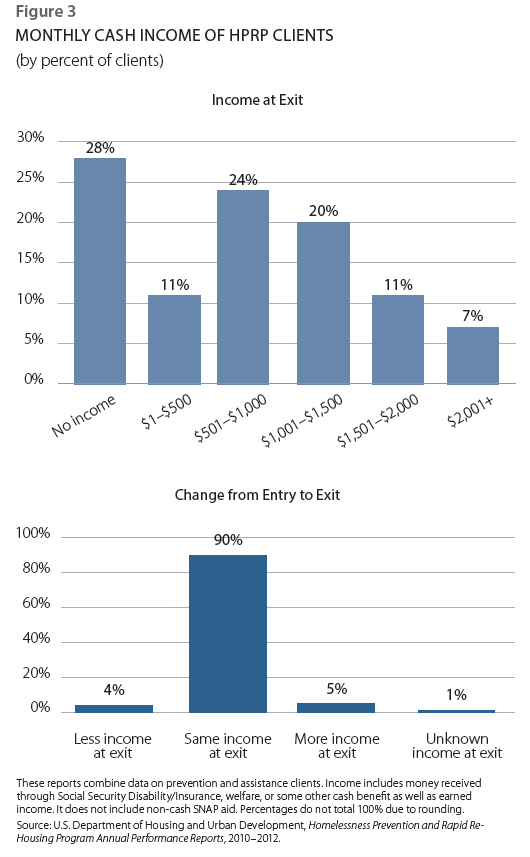

The vital importance of using household income to target services and resources is apparent when data show that 90% of all households had no change in income between entering and exiting the program (see Figure 3). Because OSH chose to target rapid-rehousing assistance only to those with sufficient income at entry, strong housing outcomes were still achieved even after assistance ended, despite income’s remaining fairly constant. The more than one in four adults who had no income at all at the end of the program likely represent households in need of more intensive service interventions or awaiting placement into permanent subsidy programs. The fact that this group made up a quarter of the population served points to the need for a multifaceted and targeted approach that includes temporary service-rich housing options, permanent housing subsidies, and rental assistance.

Lessons Learned

There is much to learn from Philadelphia’s experience. OSH did not use rapid-rehousing dollars as a panacea; instead, it used data to refine targeting for prevention and assistance moneys. Officials set parameters to direct aid to people most in need of assistance and most likely to remain stable afterward. They understood that a one-size-fits-all approach was simply not going to be the most effective way to serve all who experienced homelessness in their city.

Key to the program’s tentative success were the community conditions in Philadelphia, namely the relatively affordable housing market. By concurrently targeting the program to households with income at program entry and encouraging providers to find housing based on current instead of expected income, OSH achieved relatively stable housing outcomes. In addition, the existence of other types of housing interventions in the community enabled OSH officials to direct certain households to short-term rapid rehousing and still have transitional and supportive housing options available for those in need of more intensive services. Longer-term outcomes are needed to fully understand the results of Philadelphia’s program. Only time will tell if families remain stably housed two or more years after assistance ends. However, the city’s use of rapid rehousing as just one of many housing interventions available in the community is a large part of what has made it a promising practice so far.

Still, it is important to note that there is no single definition of rapid rehousing and that what works in one community may not work in another. Communities need to analyze, refine, and target programs based on the needs of particular homeless populations and the available local resources. As the nation pivots to rapid rehousing as the answer to homelessness, understanding for whom and under what circumstances these programs work best has never been more important. Not every household is the same. While rapid rehousing may be enough for some families and individuals, it is insufficient for many others. Acknowledging this reality and building it into efforts to address homelessness is the best way to set homeless families and individuals on a pathway to success.

Endnotes

1 “More than one in four Philadelphians lives below the federal poverty threshold”: U.S. Census Bureau, 2012 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates. “Between $11,670 for a single adult and $23,850 for a family of four”: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Federal Register 77 no. 17, January 22, 2014, 3593. “Making Philadelphia the poorest city in the United States with a population over one million”: U.S. Census Bureau, 2012 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates. “Median monthly housing cost for renters is $876”: U.S. Census Bureau, _2012 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates. “Fair market rent for a two-bedroom apartment is $1,075”: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, FY 2012 Fair Market Rent Documentation System. “57% of Philadelphia households spend at least 30% of their income on rental and other housing expenses”: U.S. Census Bureau, _2012 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates.

2 “Serving 18,743 people, 46% of whom live in families”: FY12 CoC count data have not yet been released. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2011 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress: Sheltered Homeless Persons in Philadelphia.” 6,461 emergency, transitional, and Safe Haven beds”: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2011 Continuum of Care Homeless Assistance Programs Housing Inventory Count Report.

3 ”One-time Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Rehousing Program (HPRP) grant in 2009 of $21.5 million”: Implemented during Fiscal Years 2010 through 2012 as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009, HPRP injected $1.5 billion into the national economy, targeting the most vulnerable families and individuals. ProPublica, Recovery Tracker: Listing All Stimulus Spending by Amount from Department of Housing and Urban Development (accessed November 13, 2013), http://projects.propublica.org/recovery/gov_entities/8600/list/11.”$11.2 million … was used for rapid rehousing”: Jamie Vanasse Taylor and Katrina Pratt-Roebuck, “Evaluating Philadelphia’s Rapid Re-housing Impacts on Housing Stability and Income,” presented during National Alliance to End Homelessness Conference, Washington, D.C., July 22, 2013. “To qualify for rapid rehousing” through “credit repair, and/or outreach”: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Notice of Allocations, Application Procedures, and Requirements for Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-Housing Program Grantees under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Leasing and Rental Assistance: Transition Guidance for Existing SHP Grantees Using Leasing Funds for Transitional or Permanent Housing, 2012; City of Philadelphia Office of Supportive Housing, Rapid Re-housing Program Guidelines, 2009. “Cover up to 18 months of rental assistance” through “50% or less of area median household cash income”: City of Philadelphia Office of Supportive Housing, Rapid Re-housing Program Guidelines, 2009. “OSH officials collected and analyzed data, evaluated outcomes, and changed eligibility guidelines and program procedures”: Katrina Roebuck (director of homeless prevention, City of Philadelphia Office of Supportive Housing), Dainette Mintz (deputy managing director of special needs housing, City of Philadelphia Office of Supportive Housing), and Joye Presson (chief of staff, City of Philadelphia Office of Supportive Housing), interview with ICPH, July 2012).

4 “Below 50% of the area median income”: Fifty percent of Section 8 Area Median Income for a household of one was $27,075; for two, $31,100; for three, $35,000; for four, $38,900; and for five, $42,000; City of Philadelphia Office of Supportive Housing, Homelessness Prevention Program Guidelines, 2009. ”Between $10,900 and $16,350 for a single adult and between $18,040 and $27,100 for a family of six”: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, FY 2009 Income Limits: Pennsylvania. “OSH realized that Philadelphia households” through “maintain housing even without temporary subsidies”: Katrina Pratt-Roebuck (director of homeless prevention, City of Philadelphia Office of Supportive Housing), Dainette Mintz (deputy managing director of special needs housing, City of Philadelphia Office of Supportive Housing), and Joye Presson (chief of staff, City of Philadelphia Office of Supportive Housing), interview with ICPH, July 2012.

5 “With these new guidelines in mind” through “Were more likely to return to shelter”: Katrina Pratt-Roebuck (director of homeless prevention, City of Philadelphia Office of Supportive Housing), Dainette Mintz (deputy managing director of special needs housing, City of Philadelphia Office of Supportive Housing), and Joye Presson (chief of staff, City of Philadelphia Office of Supportive Housing), interview with ICPH, July 2012.

6 Unless otherwise noted, all Philadelphia HPRP data are from U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-Housing Program Annual Performance Reports, 2010–12. “An average of $6,000”: Jamie Vanasse Taylor and Katrina Pratt-Roebuck, “Evaluating Philadelphia’s Rapid Re-housing Impacts on Housing Stability and Income,” presented during National Alliance to End Homelessness Conference, Washington, D.C., July 22, 2013. “Awaiting placement into long-term programs such as supportive housing, public housing units, or Section 8 vouchers”: In Year One, diverted households were counted under prevention in the Homeless Management Information System (HMIS). In Years Two and Three, diverted households were included under assistance, as analysis showed that those who received diversion services were more similar to persons living in shelters.

7 “13% of households who received rapid-rehousing assistance between October 2009 and July 2013 returned to shelter, compared with 39% in a matched comparison group”: The Cloudburst Group ran logistic regression using HMIS demographic characteristics comparing households in emergency shelter who did and did not receive rapid-rehousing assistance. Jamie Vanasse Taylor (The Cloudburst Group) and Katrina Pratt-Roebuck (City of Philadelphia Office of Supportive Housing), “Evaluating Philadelphia’s Rapid Re-housing Impacts on Housing Stability and Income,” presented during National Alliance to End Homelessness Conference, Washington, D.C., July 22, 2013.” A separate survey of clients six months after program exit found that 69% of respondents” through “While only half of the surveys sent out (47%) were returned”: Survey conducted by City of Philadelphia Office of Supportive Housing.