September 2018

Executive Summary

The number of English Language Learners (ELLs) who are homeless is rapidly increasing, growing by more than 50% over six years to more than 23,000 students in SY 2015–16. ELLs and homeless students alike face many obstacles to their education. However, learning English quickly—within the first three years of their education—sets these students on a path toward academic success.

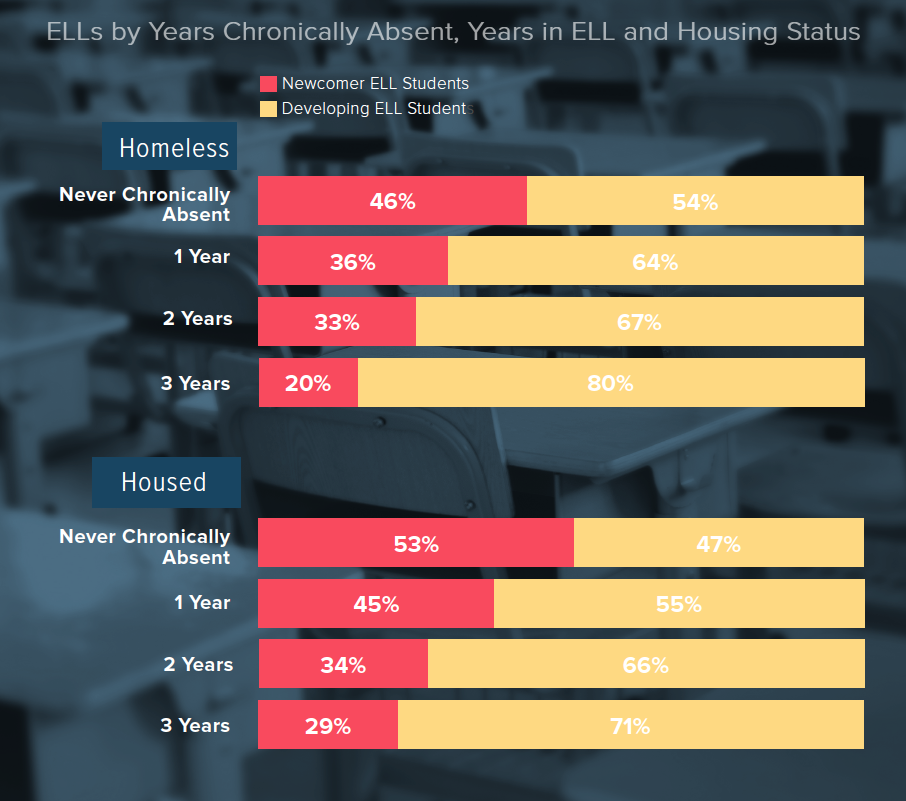

School quality, attendance, and early education play a critical role in the likelihood of a student learning English within three years. For example, homeless students who were never chronically absent were more than twice as likely to learn English within three years than their homeless classmates who were chronically absent (46%-20%).

Language spoken was also a factor—homeless ELLs who spoke Spanish were the least likely to achieve English fluency within three years.

Providing additional supports to ELL students who are experiencing homelessness is essential to ensure that housing status and language spoken do not stand in the way of a high-quality education for this growing population.

In ICPH’s first report on homeless English Language Learners (ELLs), we discussed the academic outcomes and resiliency of newcomer ELLs who learn English quickly. ELL students make up roughly one in every seven students enrolled in New York City public schools each year and speak over 160 languages. We found that when homeless ELLs learn English early—within the first three years of their education—they perform as well as or better than their classmates who already know English when they start school.

Why do some young students become fluent in English with just three years of learning while others take four, five, or six years?

This report explores what makes an ELL student more likely to be a newcomer and what strategies to use so that more students are able to learn English quickly. Targeting support at homeless ELLs (especially those attending lower-performing schools), supporting students through housing and school transitions, and ensuring that homeless students are attending pre-K are key to making sure children who do not speak English when they come to school have the same chance to succeed as their classmates who already know English.

Newcomer ELLs: Achieve English fluency in 3 years or fewer.

Developing ELLs: Achieve English fluency in 4 years or more.

Homeless, Doubled Up: Students who live with another family or with friends due to economic hardship.

Homeless, in Shelter: Homeless students who live in a New York City homeless shelter.

Other Homeless: Students who lived somewhere not meant for habitation, such as a car or outdoors.

Key Findings

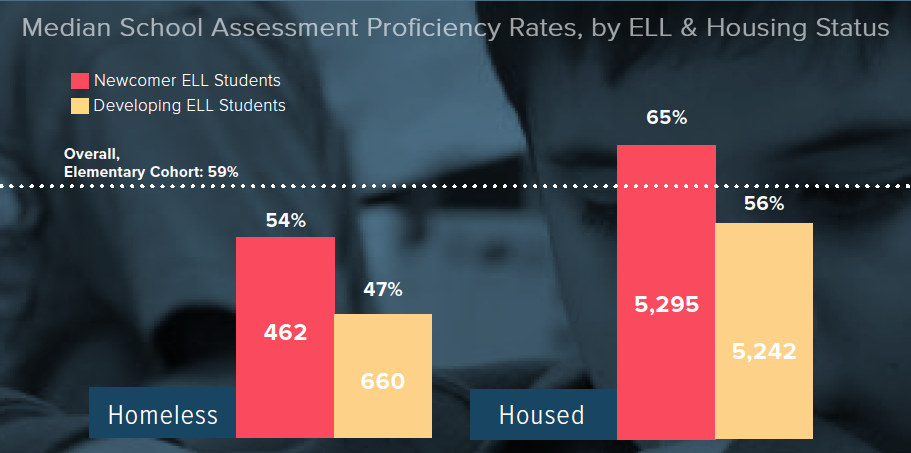

- Homeless ELL students who attend higher-performing schools learn English more quickly than those going to lower-performing schools. Among homeless students, newcomer ELLs went to schools where an average of 40% of their classmates scored proficient on statewide math and ELA assessments, while developing ELL students attended schools where the average proficiency rate was 31%.

- Spanish-speaking homeless ELL students were the least likely to be newcomer ELLs (39%).

- Homeless ELL students who speak Chinese, Bengali, Urdu, or other languages attended schools with higher proficiency rates (72%) than Spanish-speaking homeless ELLs (52%).

- Homeless ELL students who attended the same school consistently were more likely to be newcomer English learners than those who transferred schools mid-year or were chronically absent. Students who were never chronically absent were over twice as likely to learn English within three years than were their homeless classmates who were chronically absent (46% and 20%).

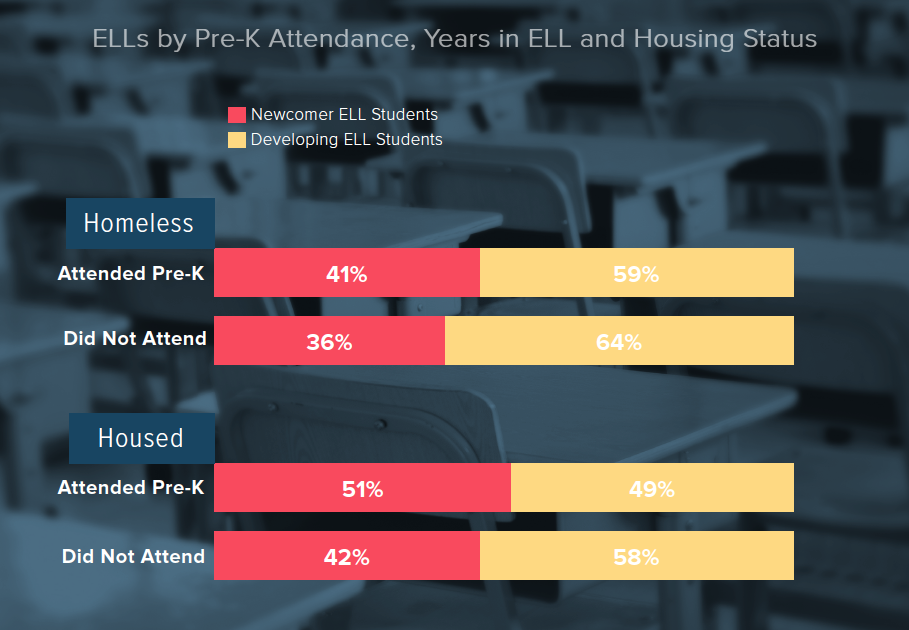

- Early education programs helped homeless ELL students learn English more quickly than their classmates who first enrolled in New York City public schools until Kindergarten. Among homeless pre-K attendees, 41% were fluent in English within three years–significantly more than those who did not attend pre-K (36%).

Quick Fluency

Why do some students become fluent in English with just three years of learning while others take four, five, or six years?

Impact of School Quality

Newcomer ELLs attend schools with overall higher State assessment proficiency rates. Among homeless students, newcomer ELLs attended schools with an average overall proficiency rate of 40% while developing ELLs attended schools where less than a third (31%) of students scored proficient, on average.

Spanish-speaking homeless ELL students were more likely to attend schools with far lower overall proficiency than their homeless ELL peers who spoke other languages (51% to 65% among newcomer ELLs). This may be one reason that homeless Spanish-speaking ELLs are less likely to become fluent in English within three years.

Impact of Absences

Attending school consistently greatly increases homeless ELL students’ chances of learning English sooner. Nearly half (46%) of homeless ELLs who were not chronically absent or did not transfer schools mid-year were fluent in English within three years.

Among homeless ELLs who transferred multiple times during the first three years of school, just one third (34%) were newcomer learners, learning English within three years. If students were chronically absent each year in Kindergarten, first, and second grades, only one in five (20%) reached fluency within three years.

Impact of Pre-Kindergarten

Given the additional support needs of homeless ELLs and their higher likelihood of chronic absenteeism and mid-year school transfers, reaching homeless families for services earlier is better. Homeless ELLs who attended pre-K were more likely to learn English within three years, regardless of language spoken: more than 40% were newcomer ELLs compared to 36% of homeless ELLs who did not attend pre-K.

Next Steps

Silos between City agencies and programs that serve homeless and ELL students must be broken down through robust partnerships and data sharing.

- New York City’s Department of Education (DOE), Department of Homeless Services (DHS), Administration for Children’s Services (ACS), and community-based organizations must prioritize not only data-sharing agreements, but strong communication pathways as well. Homeless students are more likely than others to transfer schools mid-year. When they do transfer, their language learning services must follow them. Access to individual and school-level data is essential to support homeless students through housing transitions. This data sharing can help ensure that homeless ELLs do not fall through the cracks.

- The priority of DOE and Universal Pre-K administrators should ensure that all students across New York City attend high-performing schools, especially those with additional educational support needs whose educational future is the most vulnerable. While homeless ELL students of all languages should be supported when learning English, Spanish speakers should not fall through the cracks.

SOURCE: New York City Department of Education, unpublished data tabulated by the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH), SY 2010–11 to SY 2015–16.

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, President and CEO

Aurora Zepeda, Chief Operating Officer

Katie Linek Puello, Digital Communications Manager

Project Team:

Anna Shaw-Amoah, Principal Policy Analyst

Amanda Ragnauth, Senior Policy Analyst

Kristen MacFarlane, Senior GIS Analyst

Kaitlin Greer, Policy Analyst

Hellen Gaudence, Graphic Designer