a policy brief from ICPH

June 2013

A Case Study of Mercer County, New Jersey

Government expenditures to combat homelessness in the United States have reached record levels.1 One major focus of this funding has been rapid rehousing, an approach that places homeless people in permanent housing as quickly as possible. As part of the 2009 reauthorization of the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), federal funding increased for programs that focus on rapidly rehousing the homeless.2 In a follow-up to the April 2013 policy opinion brief Rapidly Rehousing Homeless Families: New York City—a Case Study, the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness examines the strategy and implementation efforts of another location as its administrators attempt to rapidly rehouse local homeless families. This report traces events in Mercer County, New Jersey, looks at the circumstances that have informed the county’s experiences, and raises questions concerning rapid rehousing in light of results there.

Rapid Rehousing in Mercer County: Housing Now and the Family Housing Initiative

With a February 2009 award, Mercer County became one of 23 communities chosen by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to participate in the Federal Rapid Re-housing Demonstration for Families. In tandem with state money and dispensation to use Temporary Rental Assistance (TRA) grants usually reserved for families transitioning from Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) cash assistance, the Mercer County Board of Social Services (MCBOSS) implemented Housing Now, the rapid-rehousing program for homeless families in the area. The county later introduced an expanded and modified version of Housing Now, called the Family Housing Initiative (FHI). Both programs provide a maximum of 18 months of fully paid rent to already homeless families (extensions are made in certain circumstances), and county case managers make efforts to transition families from receipt of aid before they reach the maximum assistance level. The hope is that once a family is established in a residence with prevention aid or TRA, they will remain housed after cash assistance ends.3 Though initially implemented as separate pilots, Housing Now and FHI now operate using the same guidelines, with case management provided by MCBOSS and a local nonprofit organization.4

MERCER COUNTY’S APPROACH

In conjunction with the Mercer Alliance to End Homelessness (Mercer Alliance), MCBOSS designated several priorities for its rapid-rehousing program design: provide one point of entry for homeless families; develop and implement a uniform tool for assessing housing and employment barriers; aid families in finding appropriate housing; and provide wrap-around services for rapidly rehoused families to address the barriers to employment and housing retention that were highlighted during assessment.

These efforts will be described in the following section.

Single Point of Entry and Standardized Assessment

MCBOSS instituted a single point of entry for homeless services and a standardized assessment process. The county assigned TANF case managers, FHI and Housing Now staff, and employees responsible for finding jobs for parents (under Work First New Jersey) to a single facility called One Stop. There, families undergo an intake process, during which they are evaluated through a universal screening tool to determine eligibility for services. Families who are considered at imminent risk of homelessness are directed to the Family Services unit, where they can receive emergency assistance—to be applied toward owed rent or unpaid bills—to stabilize their housing.5 Homeless families are sent to emergency shelter, where, after eight days, a comprehensive assessment identifies their barriers to self-sufficiency. Based on a variety of factors, a family is placed in one of four categories. A “level 1” family is considered likely to resolve the issue causing their homelessness quickly, with a one-time infusion of assistance. Families in the “level 2” and “level 3” categories are expected to need state assistance for longer periods of time, due to employment or housing barriers such as lack of work or rental history, lack of child care, and/or insufficient education; for those families, no immediate crisis beyond a lack of housing is apparent. Families considered to be “level 4” are currently experiencing one or more immediate crises in addition to lack of housing and are expected to need intensive services for a sustained period.6

When the rapid-rehousing models were first implemented, MCBOSS used this system of levels to determine the appropriate modes of intervention. Level 1 families were expected to move back into housing on their own in short order. Families who were deemed level 2 or 3 were eligible for the county’s rapid-rehousing program and were expected to move from shelter to permanent housing within 30 days with the help of dedicated caseworkers and TRA. Level 4 families were moved to transitional housing, where they received services until their crises were resolved and they could be reassessed for program eligibility. The intention of this approach was that only families requiring the most intensive services be moved to transitional housing. After almost two years of program implementation, this strategy was modified. Currently, transitional housing as a method of intervention no longer exists in Mercer County, and all families, no matter the severity of their situations, are rapidly rehoused after 30 days if they are still in the emergency shelter system.7

Finding Appropriate Housing and Wrap-around Services

Each homeless family is assigned a caseworker who supports them during and after the housing process. To accomplish this, MCBOSS reduced caseloads, assigning billing and voucher responsibilities to a different team so that caseworkers could concentrate on social work. The caseworkers, who previously juggled 100 cases apiece on average, were allowed to focus more intensively on these most vulnerable families, managing 25 to 30 cases each and contacting every family at least once a week.8 After the initial Housing Now pilot, MCBOSS amended this approach, establishing a nine-person Rapid Exit Team, comprised of existing staff, to serve only TANF-eligible homeless families in Housing Now and FHI.9 All other families are directed to MCBOSS’s Family Services unit. Caseworkers team with parents to obtain appropriate and affordable housing. These efforts include searching for and visiting potential homes, checking for lead paint (all caseworkers are certified to do so), examining leases with parents, and, finally, negotiating preferential rental agreements with landlords. MCBOSS then makes the security deposits and rental payments.10

MCBOSS leveraged a large number of apartments subsidized by the county to negotiate rents at below-market rates, thus saving families money and increasing the likelihood that they can transition from assistance and retain their housing through earned income. Once housed, families receive wrap-around services to address employment and housing barriers.11 Caseworkers are instructed to focus on activities that will increase employment and earnings in order to give families the best chance of affording rent once rental assistance ends. However, families can also receive services that include parenting support, child care, and guidance in creating budgets.12 Families who have the greatest service needs are offered counseling for mental health and alcohol or substance dependency while housed. Caseworkers provide parents with bus passes to travel to appointments and, at the same time, apply for SSDI and other supports for those unable to work.13

The Results

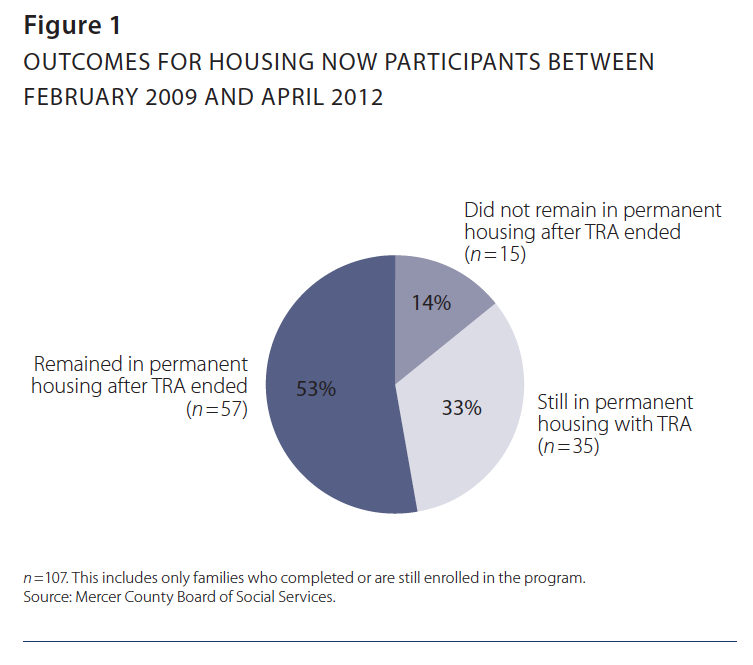

The county considers a family to have completed the program if they have received TRA for the full 18 months of eligibility or have transitioned from TRA and TANF due to income increases. Approximately one-third of the families initially enrolled in Housing Now between February 2009 and April 2012 did not complete the program; the exact number has not been released.14 During that time, 107 families completed the program or continued to receive TRA. Of those, 57 families (53%) remained permanently housed after rental assistance ended, without placement in public housing or receipt of Section 8 housing vouchers. Fourteen percent of families received TRA but were unable to sustain permanent housing after the rental assistance stopped. As of April 2012, 35 families (or 33%) were still receiving TRA as part of Housing Now (see Figure 1). The average length of receipt of TRA for all families between February 2009 and April 2012 was 301 days; the county reported that 5% of the 72 families who had completed the program returned to shelter or transitional housing after the rental assistance ceased.15

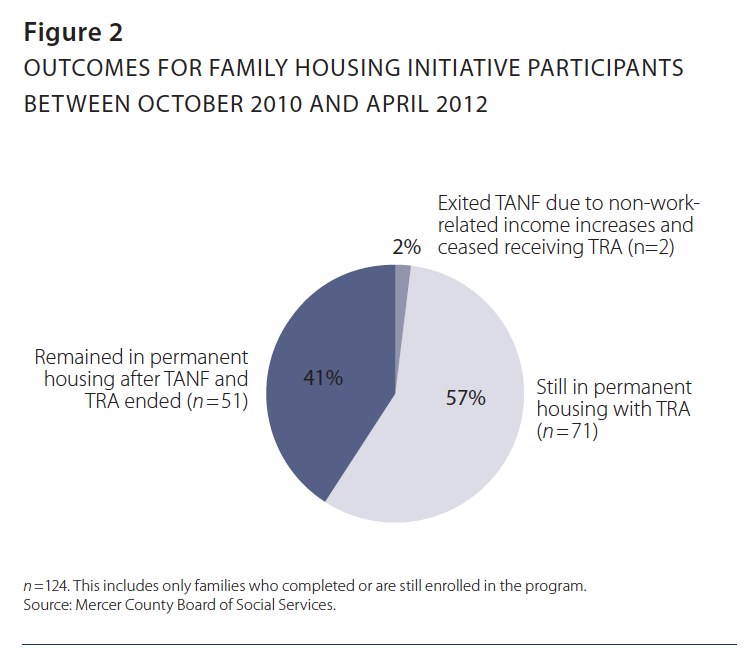

In October 2010 Mercer County implemented the Family Housing Initiative (FHI). Between its inception and April 2012, the program served at least 124 families.16 Of these, 51 exited both the FHI program and TANF due to employment and no longer received assistance. In May 2012, 71 families were still receiving TRA and using case-management services. A small handful left TANF due to increases in income outside employment (see Figure 2). Mercer County now has access to Homeless Management

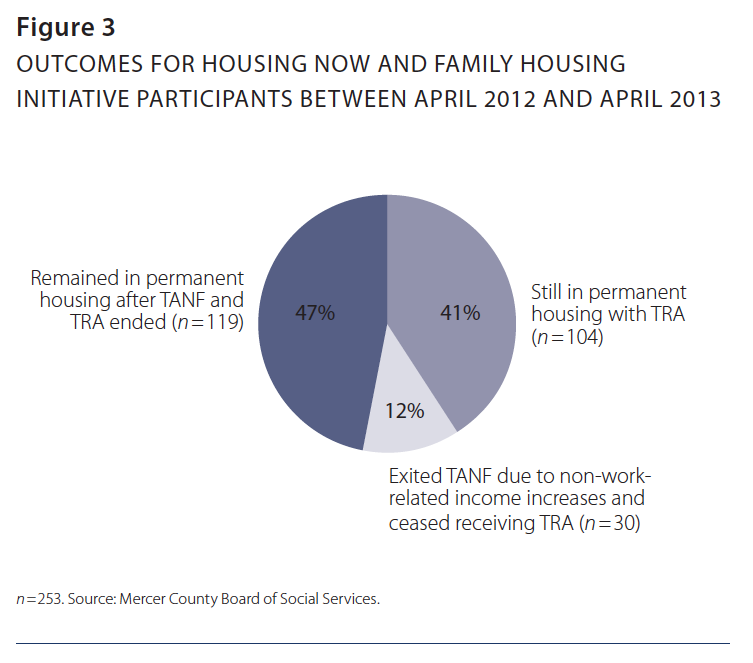

Information Systems (HMIS) data enabling reliable outcome assessment; its most recent reports show that 253 families were assigned to either the Housing Now or Family Housing Initiative program between April 2012 and April 2013. In that time, 47% of families transitioned from TRA and TANF due to increased earned income. An additional 12% exited the program due to increased income from other sources, such as SSI, SSDI, and/or child support. Of the 59% (149) of families who exited, 5% went back into the homeless-services system, unable to maintain housing. The remaining 41% of families are still enrolled in the program and receiving assistance.17

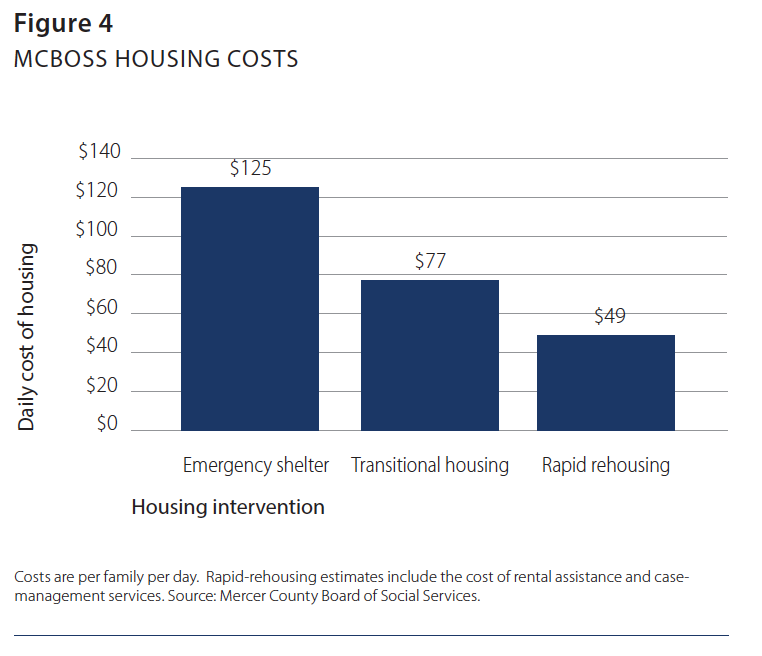

In February 2013 the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reported that the Mercer County families involved in the FHI program had an average monthly income of $835, compared with $558 for the families exiting the county’s transitional housing.18 With the reported daily cost of rapid rehousing at $49.35 (the combined cost of TRA and case management) per family, for every day that a family is in county-subsidized permanent housing as opposed to transitional housing, MCBOSS saves between $28 and $76 (see Figure 4).19

The Economics of Mercer County

What factors enabled Mercer County to implement its programs, and can they be replicated in other locales? To begin to answer this question it is necessary to understand more about Mercer County, as not all of its areas are the same. First, the housing market in Trenton has been struggling to recover from the recent economic downturn. The median value of homes is 33% lower in 2013 than in January 2009.20 This is an improvement over 2011, when home values were so low that Trenton had the third-worst housing market in the country.21

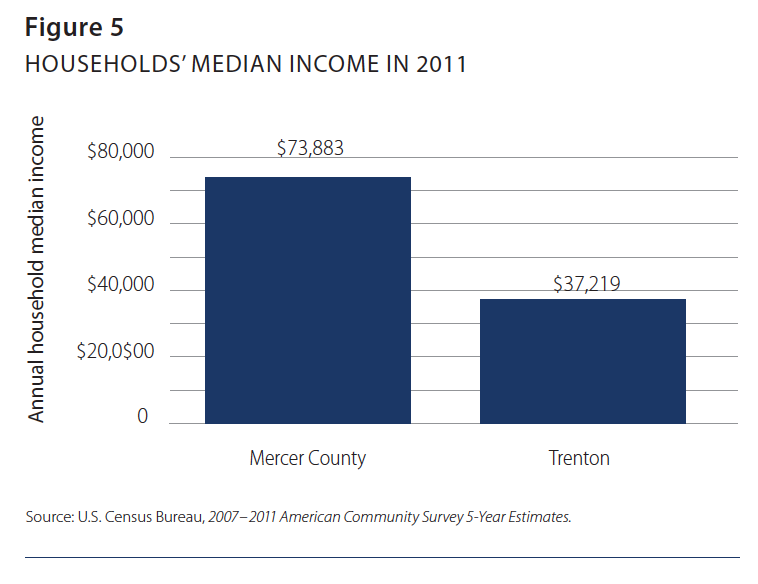

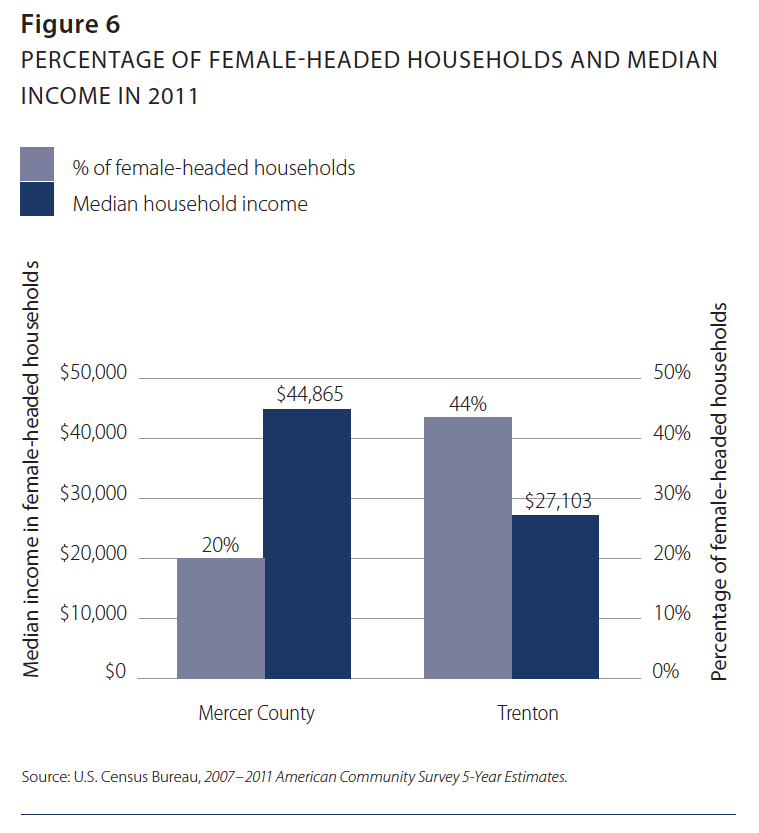

Yet the city of Trenton is an island of poverty in an otherwise wealthy county. The median household income for the city in 2011 was only $37,219, just over half of the figure for the county, which was $73,883 (see Figure 5).22 Further, Trenton is home to far more female-headed households (44%), whose median annual income was $27,103 in 2011. This is in contrast to the rest of Mercer County, in which female-headed households (20%) had a median annual income of $44,865 (see Figure 6).23 While only 3% of the county’s population received public assistance, the figure for Trenton was 9%, and the average income of the city’s residents who received public assistance was 25% less than that for cash-assistance recipients outside Trenton.24 Clearly, the county’s poor are not evenly spread across towns but, rather, are concentrated in Trenton.

Trenton is also distinct from the rest of the county in terms of its crime rate. The city was listed as the 29th most dangerous in the country among those with populations over 25,000; among cities similar in size, its violent-crime rate is one of the highest in the nation. Only 12% of cities in the country are more dangerous than Trenton.25 It is no surprise, then, that the areas of Trenton that are least safe are also the poorest in the city and have the most housing vacancies.26 Although data on where families are being rapidly rehoused is unavailable, it is worth investigating whether they are going to the most dangerous areas because those offer the greatest opportunity to negotiate low rents with landlords. The question remains whether rapid rehousing would be as cost-effective if the housing market were competitive and the neighborhoods desirable.

Conclusion

Mercer County has much of which to be proud. It has implemented a program that uses public-assistance dollars efficiently to rehouse families and save the county money. The county has not shied away from enrolling even the most difficult-to-serve families, and it has rearranged resources so that homeless families, the most vulnerable of TANF recipients, are given the extra attention they so often require. Yet questions remain. Much more research must be undertaken to fully understand the impact and scalability of rapid rehousing. It is unclear whether the negotiation of preferential rents for families, a cornerstone of the county’s success, would be possible in areas that have more robust housing markets. It is unlikely that a landlord would accept a below market rent if vacancies were few and in high demand. What happens when a family’s lease is up? Does the county step in to help renegotiate the lease, or might rent be increased at the discretion of the landlord? Furthermore, since the neighborhoods that have high vacancy rates are often also plagued with crime, poor schools, and violence,27 it is imperative that we understand whether placing families in deteriorating neighborhood conditions offsets the gains in stability the families receive from placement in permanent housing. While Mercer County’s intelligent approach has yielded compelling results in terms of cost savings, it is not clear whether even an astute design can be scaled to communities where low-income-housing deficits persist.

Though Housing Now/FHI had promising results with regard to income for roughly half of participating parents, more research is required to fully comprehend the program’s impact. The majority of homeless parents work in low-wage jobs28 that offer them the least flexibility in taking time off to care for sick children and do not accommodate situations in which normal child-care arrangements fall through.29 How will families manage the everyday pitfalls of working life while continuing to support themselves? Further, how will the families who traditionally benefit from the service-rich transitional-housing environment fare without the structure and intensive support this housing model provides? Initial results are encouraging, but rapid rehousing must be investigated on a larger scale and for a longer time to truly see its effects on earnings and shelter recidivism, given the many personal and systemic barriers that homeless families face.

Such an examination should also focus on whether and how this program affects secondary outcomes, such as children’s school attendance and achievement and parents’ pursuit of further education and career training. Rapidly rehousing families seems to be cost-effective, but is it in the families’ best interests in these other areas? To Mercer County’s credit, it acknowledges this research deficit and is looking at ways to answer these questions as the program evolves. The two years of apparent success for Mercer County’s programs deserve to be commended, but they represent the first of many steps; understanding the effect of the programs on secondary outcomes, in particular for children, is the next logical step.

Endnotes

1 U. S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, Fiscal Year 2013 Federal Government Homelessness

Budget Fact Sheet, February 2012, http://www.usich.gov/resources/uploads/asset_library/

FY13_Budget_Fact_Sheet_final.pdf.

2 National Alliance to End Homelessness, Rapid Re-Housing: Successfully Ending Family Homelessness,

May 21, 2012, http://www.endhomelessness.org/library/entry/rapid-re-housingsuccessfully-

ending-family-homelessness.

3 Frank Cirillo, White House Champions of Change, Adopting a Rapid Re-Housing Approach to

Address Family Homelessness, July 12, 2012.

4 Mercer County Board of Social Services, e-mail and telephone communications, April 2013.

5 Mercer County Board of Social Services, Serving the Community, 7th Edition, February 2012.

6 Mercer County Board of Social Services, MCBOSS Determination of Level of Intervention Flow

Chart (DRAFT), distributed during meeting on July 26, 2012.

7 Mercer County Board of Social Services, e-mail and telephone communications, April 2013.

8 Mercer Alliance to End Homelessness, Adopting a Housing First Approach: Mercer County, New

Jersey, distributed during meeting on July 26, 2012.

9 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Family Assistance, TANF-ACFIM-

2013-01 (Use of TANF Funds to Serve Homeless Families and Families at Risk of Experiencing

Homelessness), February 20, 2013.

10 Mercer County Board of Social Services, information discussed during meeting on July 26,

2012 and in e-mail and telephone communications, April 2013.

11 Mercer Alliance to End Homelessness, Adopting a Housing First Approach: Mercer County, New

Jersey, distributed during meeting on July 26, 2012.

12 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Family Assistance, TANF-ACFIM-

2013-01 (Use of TANF Funds to Serve Homeless Families and Families at Risk of Experiencing

Homelessness), February 20, 2013.

13 Mercer County Board of Social Services, e-mail and telephone communications, April 2013.

14 Mercer Alliance to End Homelessness, Adopting a Housing First Approach: Mercer County, New

Jersey, distributed during meeting on July 26, 2012.

15 Mercer County Board of Social Services, Implementing Meaningful Systems Change, distributed

during meeting on July 26, 2012.

16 Unlike Housing Now data, the FHI program data were collected not through HUD’s Homeless

Management Information Systems but by MCBOSS, making results less objective.

17 Previously, this information was obtained through provider partners. This arrangement was

modified so that MCBOSS now has direct access to HMIS data. Mercer County Board of

Social Services, e-mail and telephone communications, April 2013.

18 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Family Assistance, TANF-ACFIM-

2013-01 (Use of TANF Funds to Serve Homeless Families and Families at Risk of Experiencing

Homelessness), February 20, 2013.

19 Mercer County Board of Social Services, Implementing Meaningful Systems Change, distributed

during meeting on July 26, 2012.

20 Zillow Home Value Index, Trenton Home Prices and Home Values, January 11, 2013, http://

www.zillow.com/local-info/NJ-Trenton-home-value/r_41279/#metric=mt%3D34%26dt%3D

1%26tp%3D6%26rt%3D8%26r%3D41279%252C276250%252C276571%252C275868%26

el%3D0 (accessed January 28, 2013).

21 Vanessa Wong, “Not Every Real Estate Market Is Struggling,” BloombergBusinessweek Lifestyle,

October 21, 2011.

22 U.S. Census Bureau, 2007–2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates (Table S1903).

23 U.S. Census Bureau, 2007–2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates (Table S1903).

24 U.S. Census Bureau, 2007–2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates (Table S1902).

25 Neighborhood Scout, Crime Rates for Trenton, NJ, http://www.neighborhoodscout.com/nj/

trenton/crime/ (accessed January 28, 2013).

26 Ibid. City-Data.com, Trenton, New Jersey, Vacant Housing Units (%) Based on 2005–2010 Data,

http://www.city-data.com/city/Trenton-New-Jersey.html (accessed January 28, 2013).

27 Neighborhood Scout, Crime Rates for Bronx, NY, http://www.neighborhoodscout.com/nj/trenton/

crime/ (accessed January 28, 2013); Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness,

The Impact of School Closures on Homeless Students in New York City, September 2010; Institute for

Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, A Bronx Tale: The Doorway to Homelessness in New York

City, February 2012.

28 25% of New York City parents experiencing homelessness work as home-health aides, in child

care, or in personal services—for example, in the beauty industry; 21% work in retail or

sales; 19% work in security or maintenance. Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

National Family Homeless Database.

29 Center for Children’s Initiatives, When Families Eligible for Child Care Subsidies Don’t Have One

(2010), http://nynp.biz/CCIReport.pdf (accessed January 9, 2013).