Executive Summary

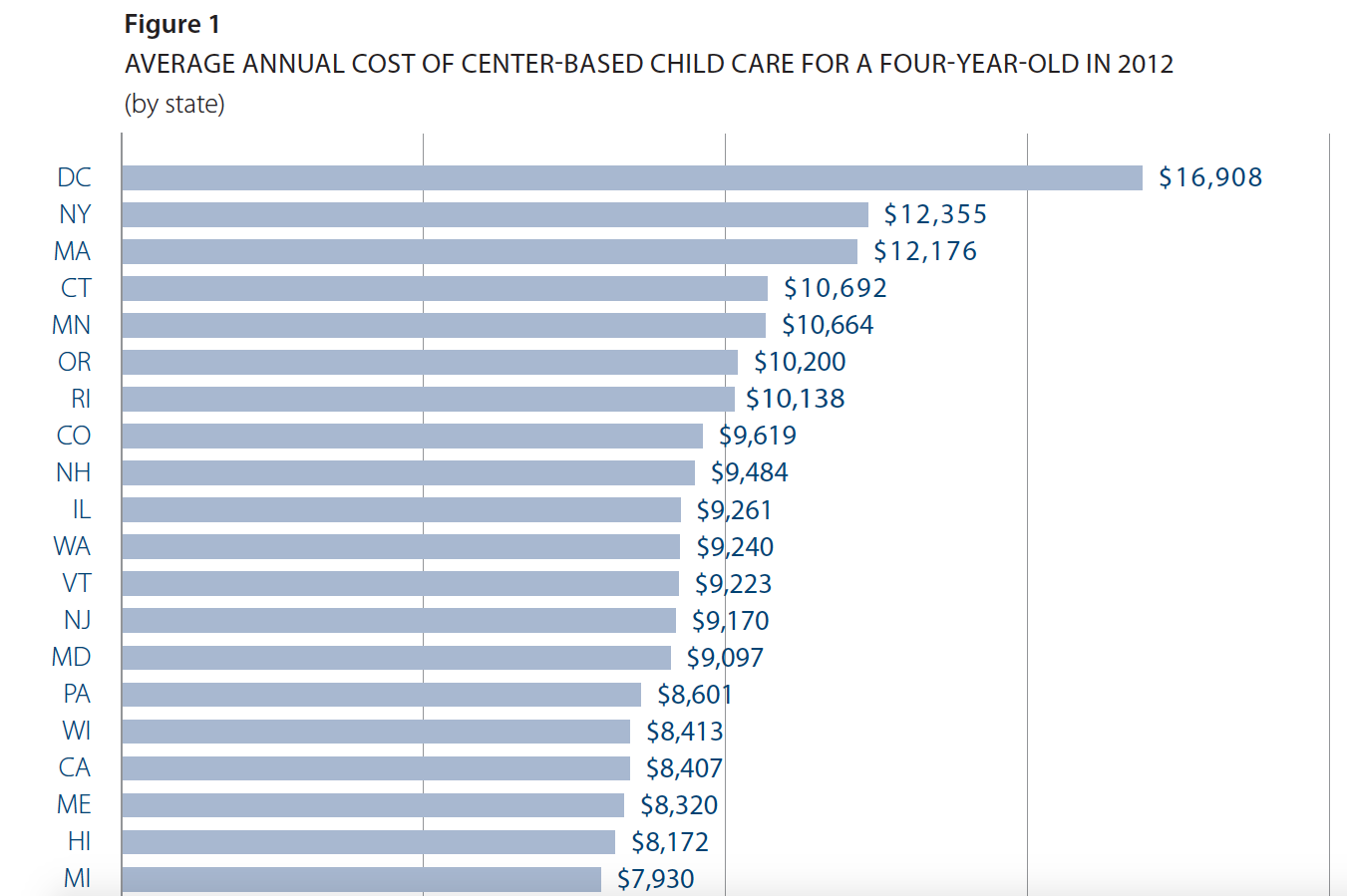

Without access to child care, homeless families struggle to secure housing. Having a safe and stable child care arrangement allows homeless parents to look for and maintain work and participate in the job training, education, and other programs essential to resolving their homelessness. Yet, homeless families face many barriers to accessing child care; homeless mothers are actually less likely to receive child care subsidies than poor housed mothers.1 With the annual cost of center-based care for a four-year-old averaging $7,817, nearly half the federal poverty line for a family of three, the high cost of care presents one obstacle.2 Finding a child care provider who can accommodate homeless families’ often irregular, unpredictable, and inflexible schedules can also be challenging. In addition, restrictive documentation and eligibility requirements can prevent homeless families from qualifying for—or even seeking—subsidized care.

The main federal source of child care assistance for low-income families is the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF). States administer this block grant using their own eligibility guidelines, which can include policies to improve homeless families’ access to care. Every two years, states submit plans to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services describing how they will manage their child care subsidy programs over the subsequent two-year period. The Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH) analyzed each state’s CCDF plan for federal Fiscal Years 2014–15 and found that the majority of states do not have policies in place that ease and encourage homeless families’ use of child care subsidies:

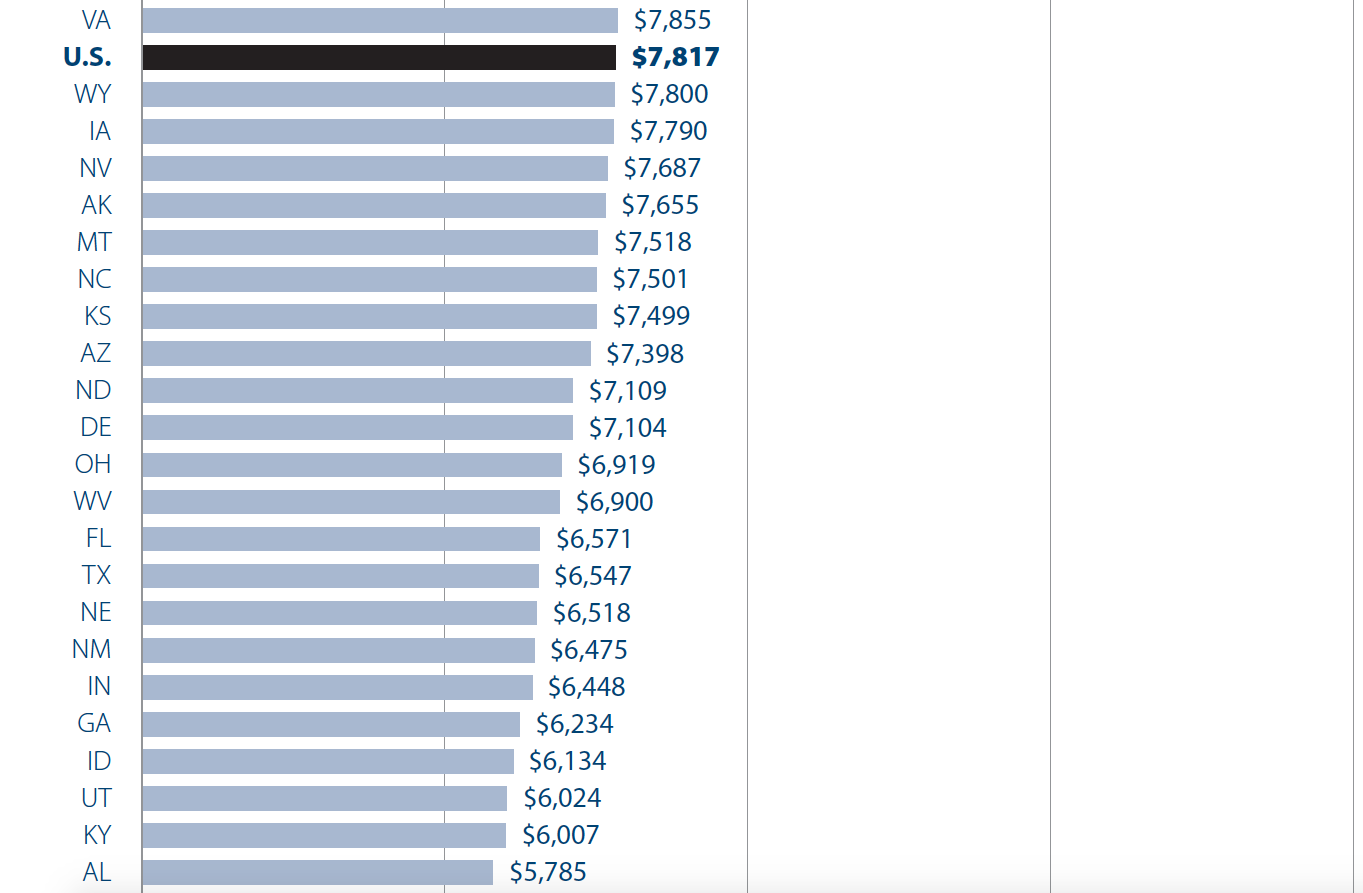

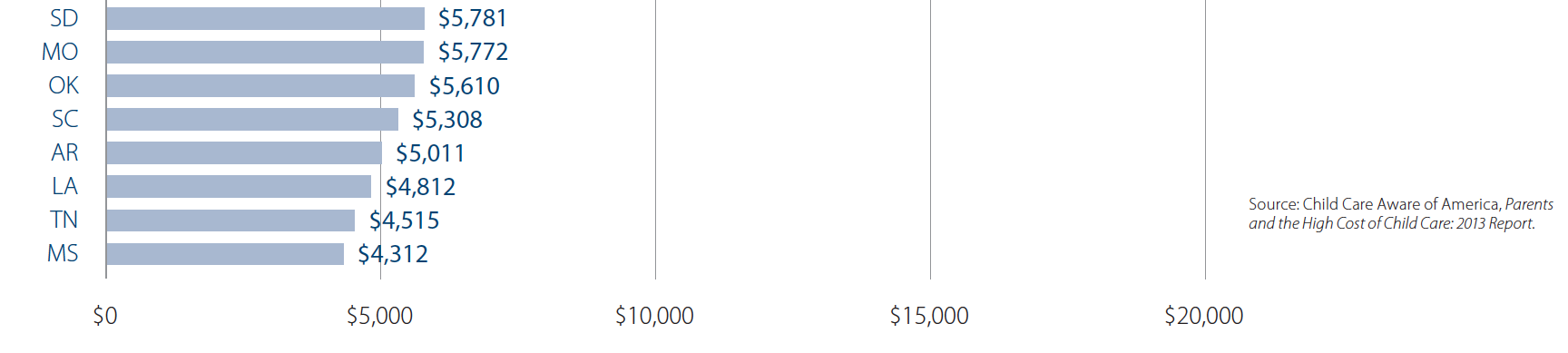

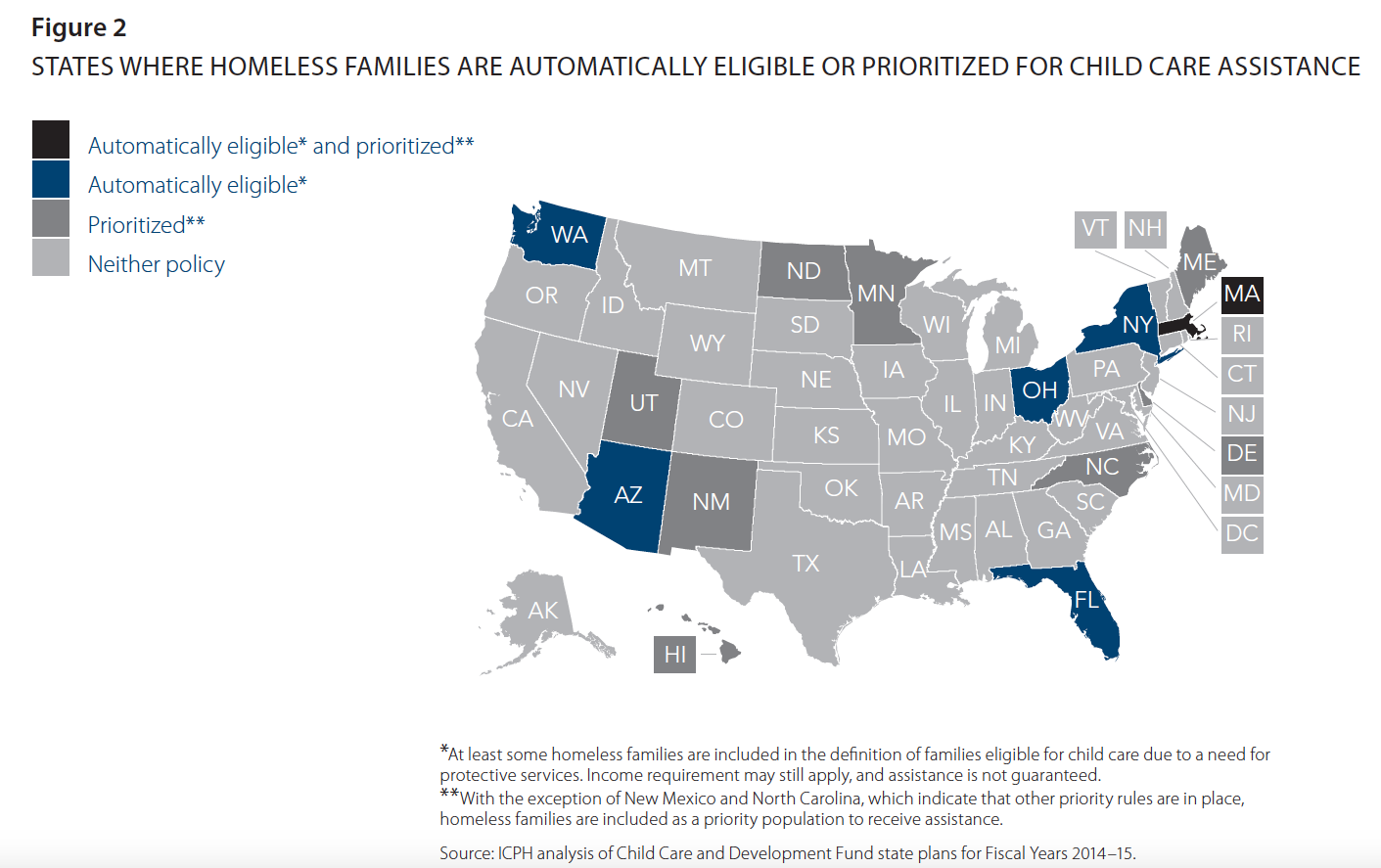

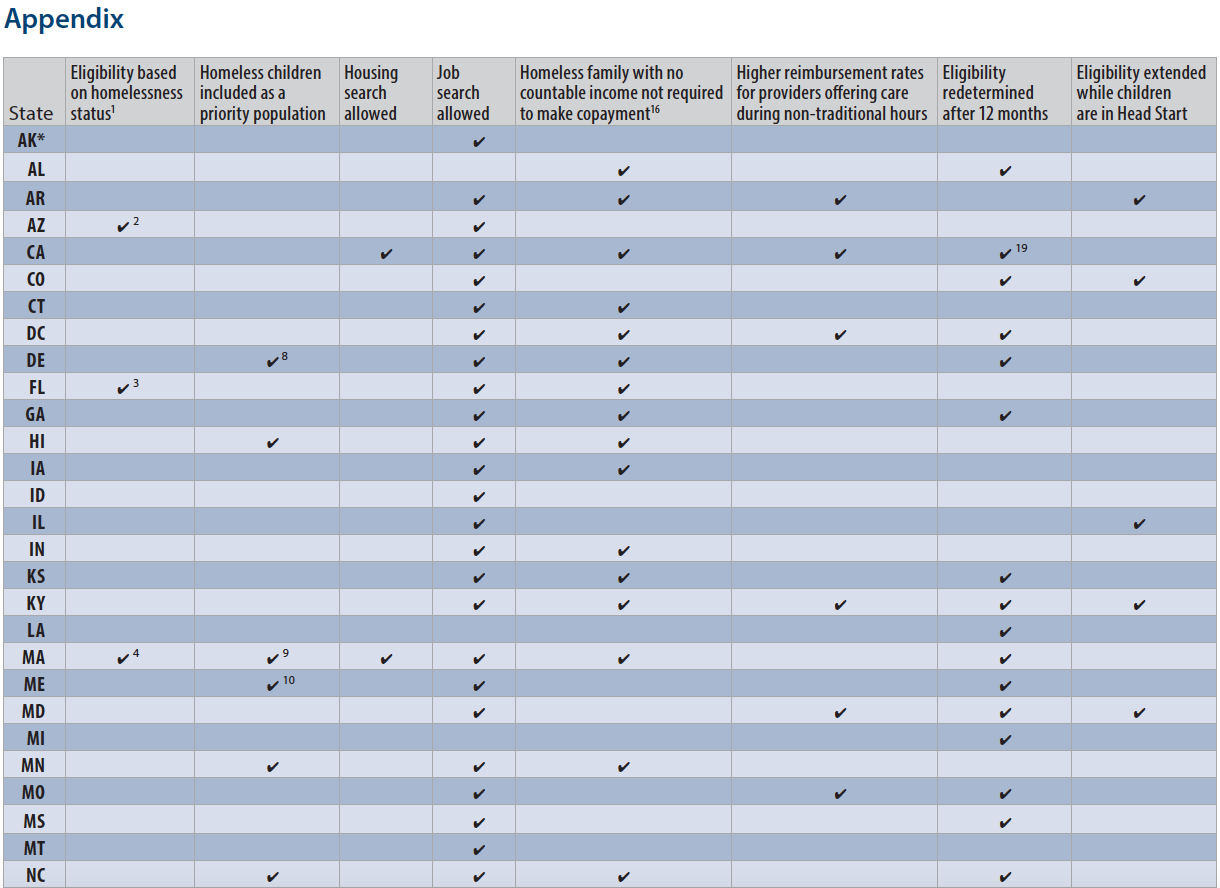

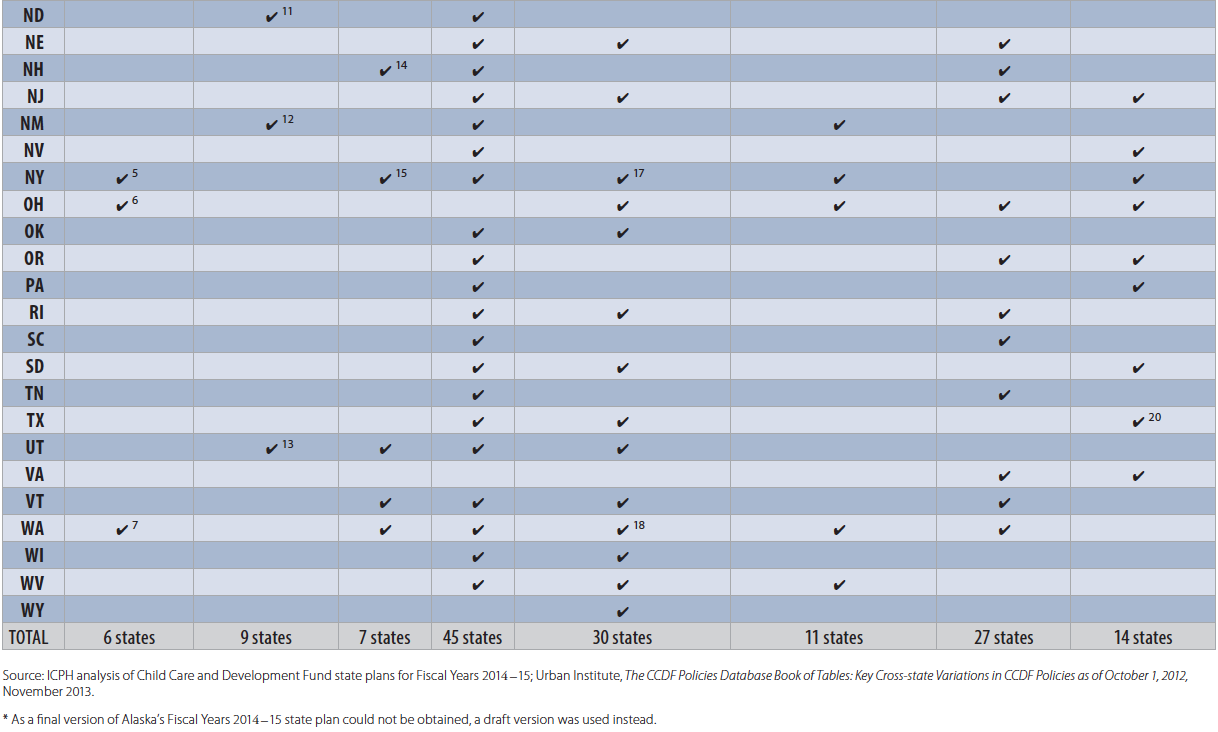

- Only six states include homeless families in the definition of those with protective-services needs, enabling them to qualify for care without meeting traditional eligibility requirements.

- Only nine states include homeless children as a priority population.

- At least 24 states require families applying for child care to provide birth certificates or other documentation that can be challenging for families experiencing homelessness to locate.

- All but six states provide child care to at least some parents while they search for work, but only seven states do so while parents look for housing.3

- Thirty states waive copayment fees for homeless families or families with no countable income.

- Only 11 states have higher reimbursement rates for providers offering child care during nontraditional hours, such as nights and weekends.

- Twenty-seven states will provide subsidized care for 12 months before reevaluating a family’s eligibility, offering families continuity of care, and 14 states extend eligibility while children are in Head Start.

- Overall, only 18 plans mention homeless families or services specific to them. No state listed programs serving homeless children as having been consulted in the drafting of the CCDF plan.

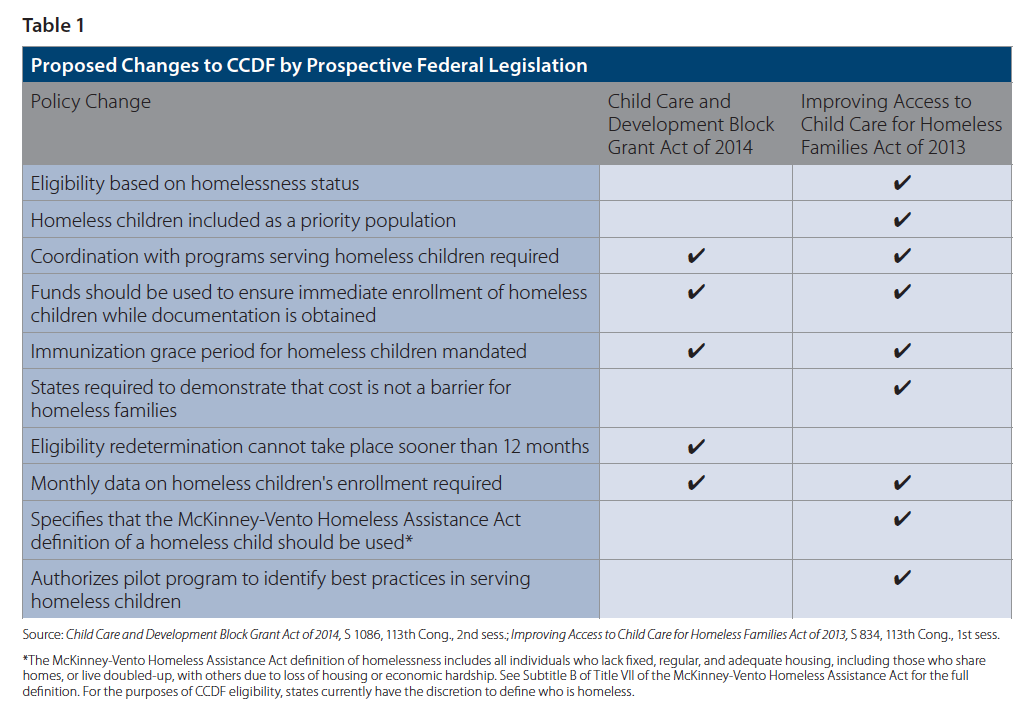

Homeless children, among the most vulnerable children, deserve a safe place to learn and grow while their parents search for a job and return to stable housing. Pending federal legislation, the Child Care and Development Block Grant Act of 2014 and the Improving Access to Child Care for Homeless Families Act of 2013 would greatly improve homeless families’ access to subsidies. Given the flexibility they have in administering CCDF, however, states should not wait for action at the federal level. ICPH’s analysis of states’ CCDF plans highlights several policies that every state should implement to reduce the unique barriers homeless families face in finding and maintaining child care. Similar policies have already been enacted to ensure homeless children equal access to public education and increase enrollment in Head Start; it is now time to apply the lessons learned from those past successes to child care.

Introduction

In most cases a homeless family is headed by a single mother with two children, with at least one child under the age of six.4 Without safe and reliable care for their children, homeless mothers cannot search for or sustain employment or access the job training, education, and other services essential to resolving their homelessness. Federal and state subsidized child care, designed to support low-income families’ self-sufficiency, should be a resource for the most vulnerable of families—those experiencing housing instability. Yet, the number of child care subsidies available is not sufficient to meet demand, and the current structure of the child care system undermines homeless families’ ability to enroll.

Administered by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) is the primary source of child care subsidies for low-income families. Individual states determine how their share of CCDF funding is spent and who ultimately is eligible for care. In setting their eligibility guidelines and priorities, states have the opportunity to eliminate several of the structural barriers homeless families face in accessing child care. The Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH) analyzed each state’s CCDF plan for federal Fiscal Years 2014–15 and found that while some states have taken steps to do so, the majority of states do not have policies in place to promote homeless families’ access to subsidized child care.

Child Care Supports Children’s Development and Families’ Self-sufficiency

For homeless families, accessing child care offers two important benefits—a safe setting for children to grow and learn and the opportunity for parents to sustain a stable connection to the workforce. High-quality child care can, especially for young children, bolster the early learning skills necessary for success in school and beyond.5 By modeling nurturing interactions and behaviors, child care providers help shape young children’s development: having child care offers homeless parents the chance to observe positive caregiving practices, which can influence their own parenting.6 Child care providers can also support homeless parents in managing any concerns they have related to their children’s behavior and development.

Child care plays a critical role in supporting homeless parents’ employment. Without first arranging care for their children, homeless mothers cannot look for work or participate in the education and training programs necessary to improve their employability.7 Studies have shown that child care subsidies have a positive effect on low-income parents’ work participation.8 Subsidy recipients are not only more likely to be employed than those who do not receive subsidies but also work more—nearly ten hours more per week on average, according to one national study—and for longer periods.9 By supporting parents’ ability to work and meet more of their families’ basic needs, child care strengthens families’ overall economic security and helps prevent future episodes of homelessness.

Homeless Families Encounter Many Barriers to Accessing Child Care

A 2012 ICPH report found that homeless mothers are less likely to receive child care subsidies than both mothers who are at risk of becoming homeless and mothers who are stably housed.10 Research has also shown that low-income families receiving subsidies have higher incomes and report fewer risk factors than eligible non-recipients, which suggests that the child care subsidy system is particularly difficult for more vulnerable parents to navigate.11 Homeless parents face several barriers to accessing and maintaining high-quality care for their children, including the high cost of care, inflexible care arrangements, lack of awareness of care options, and prohibitive documentation requirements.

One of the most significant obstacles is the high cost of child care. In 2012 the average annual cost of center-based care for a four-year-old was $7,817, ranging from $4,312 in Mississippi to $16,908 in the District of Columbia (see Figure 1); and the cost of care increases for infants and children with special needs.12 Subsidies bring the cost of care down substantially—the average fee for subsidized care in Fiscal Year 2012 equaled 5% of a family’s income, or $990 a year for a family of three at the federal poverty level.13 However, even a reduced fee could be unmanageable for homeless families with few, if any, financial resources.

Like many low-income families, those experiencing housing instability often work in low-wage jobs with nonstandard and unpredictable hours and little workplace flexibility. Finding high-quality child care providers who can accommodate their work schedules, which may include overnight or weekend shifts, can be difficult.14 The unstable employment patterns and high mobility that accompany homelessness can also cause homeless children to be absent from care frequently. Families can lose their subsidies for excessive absences, and providers who are reimbursed based on the number of hours of care they provide can lose revenue as a result of irregular participation.

Lack of information or misinformation can also limit homeless parents’ child care choices. Low-income families tend to rely on informal sources and networks such as family and neighbors to help them make decisions about child care.15 Many parents do not know that they can get help paying for child care; those who know can be deterred from utilizing child care subsidies due to the complexity of the application process and both perceived and real eligibility restrictions, such as programs’ documentation requirements.16 Families applying for subsidies may be required to provide birth records or proof of residency or citizenship, documents that are often difficult for homeless parents to produce immediately.

State-level Implementation of CCDF

More than 900,000 families and 1.5 million children receive child care assistance each month through CCDF.17 Federal guidelines state that to be eligible, a child must (1) be under 13 years old or under 19 and physically or mentally incapable of caring for himself or herself, (2) reside with a family whose income does not exceed 85% of a state’s median income (SMI), and (3) reside with a parent or parents who are working or attending an education or job-training program or need to receive protective services.18 As CCDF is a block grant and not an entitlement program, states are not mandated to provide assistance to all eligible applicants. HHS estimates that only one in six eligible children receives assistance.19

States are given the flexibility to establish rules to supplement these broad federal guidelines.20 These include setting their own income limits, at or below 85% of SMI, as well as family copayment levels (the portion of the cost of care that subsidy recipients pay) and reimbursement rates to child care providers. In addition, states have the discretion to define the activities that fulfill work or education requirements and determine which vulnerable children have protective-services needs. States may also prioritize certain eligible families for assistance, including those experiencing homelessness. The decisions states make affect not only families’ eligibility but also the quality of subsidized care they can reasonably expect to access.

Every other federal fiscal year, states must submit detailed plans to HHS describing how CCDF will be administered over the subsequent two-year period, including the additional eligibility rules they will set. Since each state must answer the same questions, developed by HHS, the plans highlight differences in their approaches and provide insight into the number of barriers homeless families can face in securing child care assistance. ICPH evaluated the CCDF plans for Fiscal Years 2014–15 for every state and the District of Columbia in order to determine how many states consider the unique needs of homeless families in designing and implementing their child care programs.21

Policies that could either facilitate or constrain homeless families’ access to child care were identified and selected for analysis. Specifically, ICPH reviewed whether states consider homeless families to have protective-services needs, include homeless children as a priority population, require documentation with applications, provide care while parents look for work or housing, waive fees for low-income families, incentivize child care providers to serve homeless families, and have policies to promote continuity of care for homeless families. When this information was not provided entirely by the state plans, ICPH consulted individual state agencies and the HHS-funded CCDF Policies Database.22 While this analysis is not a comprehensive account of all the CCDF rules or policies that could affect homeless families’ access to subsidies, it does include the most pervasive enrollment barriers.

Eligibility and Priority Based on Homelessness Status

By including families experiencing homelessness in the definition of families eligible for care due to a need for protective services, states indicate that homelessness alone is a reason for needing care and enable homeless families to qualify for assistance without first meeting the typical work requirements. Although the instructions for completing this section of the state plan remind states that they have the option to include homeless children, only six states, according to the 2014–15 state plans, include at least some homeless families in this definition: Arizona, Florida, Massachusetts, New York, Ohio, and Washington (see Figure 2). With the exception of Arizona, all of these states will also waive the copayment and income requirements for families on a case-by-case basis, making it even more likely that a homeless family will be found eligible and able to afford care. Arizona does so only for children with Child Protective Services case plans, so homeless families not connected to the child protective-services system are still restricted by those additional requirements.

States have the flexibility to prioritize for assistance certain children with special needs and children in families with very low incomes. The question related to this on the state plan specifically notes that states can prioritize homeless children; nevertheless, only seven states do: Delaware, Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, North Dakota, and Utah (see Figure 2). Two additional states, New Mexico and North Carolina, indicate that other priority rules are in place for homeless children. Of these nine states, six described mechanisms to ensure that these children have priority access, including waiving copayments, placing families at the tops of waiting lists, and offering incentives (such as higher reimbursement rates) to providers serving them. North Dakota, for example, prioritizes quality-improvement funding and offers specialized on-site consultation and technical assistance for providers serving children with special needs, including homeless children (see Appendix for details on each state).

Easing Restrictive Documentation Requirements

Even if every state included homeless families in the definition of priority populations, prohibitive documentation requirements would still exist, discouraging some of these families from even seeking assistance. Most homeless families do not have immediate access to birth certificates, immunization records, or documents showing proof of citizenship or residency. Nearly half (24) of states require families applying for assistance to provide birth records for the child in need of care or other documentation of the child’s identity and age. This, moreover, is a conservative estimate, as it does not include states that first electronically verify the child’s identity before seeking documentation from applicants. According to the plans, at least five states follow this procedure, but states are not specifically asked whether they do. Families without existing records in statewide databases would be expected to provide documentation in those states.

States are not required to indicate if there are grace periods in place for families to provide required documentation. Preliminary analysis of states’ child care licensing regulations suggests that some states have not instituted grace periods for families to meet immunization requirements, while in the states that have them, the length may range from as short as two weeks to as long as six months.23

Adding Housing and Job Search as Eligible Activities

In addition to work, job training, and education, states may include housing and job search as activities that homeless parents can participate in to meet their programs’ eligibility requirements. Given that the majority of homeless mothers living in shelters are not working, adding both as eligible activities would eliminate yet another barrier to accessing child care.24 According to the CCDF Policies Database, only seven states include housing search as a qualifying activity in at least some cases.

The 2014–15 state plans indicate that all but six states provide child care to at least some parents while they look for work. The conditions under which this is allowed differ by state. While states are not required to describe those details in their plans, the CCDF Policies Database notes that as of 2012, 16 states allow only parents who lose their jobs while receiving subsidies to obtain assistance for job search. The maximum amount of time given for job-search activities also varies, ranging from as little as 80 hours in Alaska and 150 hours in Utah to a year or more in the District of Columbia and Idaho. The median time limit across all states for parents to find work is 56 days, or nearly two months.

Reducing the Cost of Care

Families receiving child care subsidies are expected to pay for a portion of the care provided. States decide how much families will pay and are required to set fees on a sliding scale based on income and family size. States have the option to waive copayments only for families included in the definition of those with a need for protective services (as discussed earlier) and families whose incomes are at or below the federal poverty level. As the average income of homeless mothers falls well below the federal poverty level, any fee can be prohibitive.25 Analysis of all the information in the 2014–15 state plans related to copayment fees and exemptions reveals that in 30 states homeless families with no countable income would not be required to pay for care. In the remaining states, the average monthly fee as a percentage of family income ranges from 2% to 15%.26

Family-friendly Provider Reimbursement Policies

States may pay higher reimbursement rates for child care provided during nontraditional hours and reimburse providers when children are absent from care. Both policies are essential for homeless parents, who regularly face unpredictable work schedules and often move from one tenuous housing arrangement to another. Eleven states pay child care providers more for offering care during nontraditional hours, which are generally considered to be between 6:00 p.m. and 6:00 a.m. on weekdays and to include all weekend hours. However, the financial incentive to providers differs widely across these states; in Kentucky providers offering nontraditional hours are given only an additional $1 per day.

States also handle absences differently; some reimburse child care providers up to a maximum number of absences per month or year, while others allow child care providers to bill for a full week or month of care as long as the child attended the program at least once. Providers who are reimbursed based on the number of hours children are in care rather than enrollment may be less inclined to serve homeless families with highly irregular or unstable schedules, fearing that their children will be absent often.27

Promoting Continuity of Care

Child care assistance is time-limited. After a set period of time, states review families’ income and work or education status in order to determine if they are still eligible. Continuity of care is critical, however, both for child development and for ensuring that homeless parents can work toward stable employment and self-sufficiency without disruption. In large part to promote stable caregiving for children, HHS advises that eligibility redetermination occur no sooner than 12 months after initial subsidy receipt, but analysis of the state plans indicates that only 27 states follow this recommendation.28 Of the remaining states, the vast majority schedule eligibility redetermination only six months after initial receipt.29

Since homeless families are categorically eligible for Early Head Start and Head Start services,30 states can promote continuity of care by extending child care subsidy eligibility for families already enrolled in either program. Fourteen states have instituted this policy, and while most of those do not schedule redetermination for these families until the end of the program year, some have even more generous policies. Pennsylvania, for example, does not schedule child care eligibility redetermination until the child is no longer enrolled in Head Start.

Policy Recommendations

The CCDF state plans for Fiscal Years 2014–15 indicate that while many states have policies in place to facilitate homeless families’ access to child care assistance, the majority of states are not adequately addressing those families’ unique needs. Overall, only 18 states mentioned in their plans homeless families or services specific to families experiencing homelessness. No state has instituted all of the policies examined in this report; even those states with some generous policies toward homeless families have room for improvement.

The first major overhaul of the child care system in nearly 20 years, the Child Care and Development Block Grant Act of 2014, would make a number of improvements to support homeless families’ access to care.31 The bill requires the state agencies responsible for managing CCDF to coordinate with programs serving homeless children and establish a grace period for those children to meet immunization requirements. The bill also specifies that funding should be used to promote immediate enrollment of homeless children while documentation is obtained, training in identifying and serving homeless children, and outreach to homeless families.

The Improving Access to Child Care for Homeless Families Act, introduced in the U.S. Senate in both 2012 and 2013, would make these and additional improvements, including establishing homelessness as an eligibility category, identifying homeless children as a priority population, and requiring states to demonstrate that the cost of care is not a barrier for homeless families. Both pieces of legislation would require states to track and report homeless children’s enrollment, information that would elucidate states’ progress in reaching homeless families. Table 1 compares the two pieces of legislation with regard to many of the policies examined in this report.

Given the flexibility states have to administer CCDF, states should not wait for the federal government to act to make important improvements for homeless parents and their children. First, all states should include homeless families in the definition of families with protective-services needs and create mechanisms to prioritize homeless children for assistance. Second, states should institute policies to remove barriers for homeless families to participate in the program, including policies waiving copayments, eliminating documentation requirements, establishing a grace period for immunizations, adding housing and job search as eligible activity requirements, incentivizing providers to offer care during nontraditional hours and reimbursing those serving homeless families for absences, and setting eligibility redetermination periods at 12 months.

Although states have an opportunity in their plans to describe the state and local entities with whom they consulted in developing them, no state mentioned homeless service providers. The lead CCDF agency in each state should collaborate with the state coordinator of homeless education and local homeless-education liaisons to identify and address gaps in service delivery. In addition, states should establish contracts with homeless service providers or otherwise set aside subsidies for homeless families with children.32 States may also use a portion of the quality improvement activity funds they are allotted to address the needs of homeless families—for example, by establishing pilot projects evaluating homeless families’ access to care, supporting outreach to homeless families, or educating child care providers about the unique characteristics and needs of homeless children and their parents, among other innovative strategies.33

States are required in crafting their state plans to hold at least one public hearing to solicit feedback and ideas about how CCDF should be implemented, providing a forum to raise awareness of homeless families’ needs. While the plans that cover Fiscal Years 2014–15, evaluated in this report, have been finalized, the next local hearings will likely take place in the spring of 2015 and will inform the development of the plans for Fiscal Years 2016–17.

Conclusion

Existing laws related to homeless children’s education establish a precedent for amending CCDF. The reauthorization of the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act in 2002 provided hard-won protections for school-age homeless children. To ensure that homeless children have equal access to public education, the act removed many barriers to enrollment, including restrictive immunization and documentation requirements, and formalized processes for identifying homeless children. Similar policies can and should be applied to CCDF. Additionally, the Improving Head Start for School Readiness Act of 2007, which made young homeless children categorically eligible for Head Start services, provides a model for how homeless children could be prioritized for child care. Both acts demonstrate that many of the issues discussed in this report are not new and that similar solutions have already been successfully employed nationwide. The improvements that should be made to the child care subsidy system are both possible and practical and would have a substantial impact on the stability and self-sufficiency of the country’s most vulnerable families and children.

Appendix Notes

1 Homeless children eligible for child care due to a need for protective services. States may include any vulnerable or at-risk children in their definition of “protective services.” If a child is eligible for care due to a need for protective services, his or her parent may not be working or participating in job training or education activities.

2 Includes families who are unable to provide child care for a portion of a 24-hour day due to a crisis situation of homelessness. Copayments and income requirements not waived.

3 Includes any child in the custody of a parent who is considered homeless as verified by a Florida Department of Children and Families certified lead agency. Copayments and income requirements waived on a case-by-case basis.

4 Includes families who are unable to provide child care for any portion of a 24-hour day due to homelessness. Copayments and income requirements waived on a case-by-case basis.

5 Local social service districts may include homeless families with income up to 200% of the state income standard when child care is needed to participate in an approved activity or screening for victims of domestic violence. Copayments and income requirements waived on a case-by-case basis.

6 Homeless families must have a case plan or reside in an emergency shelter for homeless families or be identified as homeless by the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services. “Homeless protective child care” is limited to 90 days over 12 months or the period of time that the family is homeless (whichever is shorter). Copayments and income requirements waived on a case-by-case basis.

7 Includes homeless children. Copayments and income requirements waived on a case-by-case basis.

8 Higher reimbursement rates are offered to providers.

9 Copayments waived on a case-by-case basis. Massachusetts Department of Early Education and Care contracts with providers offering child care services to homeless children.

10 Families given priority if placed on a waiting list.

11 Quality funds prioritized for providers serving these children. Providers may receive free on-site consultation and technical assistance to aid in delivering high-quality care to children with special needs.

12 Families prioritized should a waiting list be maintained.

13 Copayments waived for families with incomes at or below the federal poverty level.

14 Housing search qualifies only if subsidy recipient is also looking for work.

15 Varies by local social service district.

16 State waives copayments specifically for homeless families and/or families with no countable income. A homeless family could qualify for a fee exemption in a state for other reasons, such as receipt of temporary assistance or Supplemental Security Income.

17 Applies to homeless families who are identified as needing child care due to protective-services needs, and varies by social service district. Some homeless families may be asked to provide copayments.

18 Determined on a case-by-case basis.

19 Redetermination scheduled at three months for at-risk families.

20 Up to localities to decide.

Endnotes

1 Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, Profiles of Risk: Child Care, 2012.

2 Child Care Aware of America, Parents and the High Cost of Child Care: 2013 Report; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “2014 Poverty Guidelines,” http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/14poverty.cfm.

3 As states are not required in the CCDF plans to describe whether child care is provided during periods of housing search, this information was obtained from the CCDF Policies Database; Urban Institute, The CCDF Policies Database Book of Tables: Key Cross-state Variations in CCDF Policies as of October 1, 2012, November 2013.

4 Debra J. Rog, C. Scott Holupka, and Lisa C. Patton, Characteristics and Dynamics of Homeless Families with Children: Final Report to the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Human Services Policy, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2007.

5 A large body of literature supports the connection between high-quality early childhood education and care and child outcomes; Jack P. Shonkoff and Deborah A. Phillips, eds., From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2000); W. Steven Barnett, “Effectiveness of Early Educational Intervention,” Science 333, no. 6045 (2011): 371–99.

6 Kevin J. Swick, “Empowering the Parent–child Relationship in Homeless and Other High-risk Parents and Families,” Early Childhood Education Journal 36, no. 2 (2008): 149–53; Kevin J. Swick, “Strengthening Homeless Parents with Young Children Through Meaningful Parent Education and Support,” Early Childhood Education Journal 36, no. 4 (2009): 327–32; Kevin J. Swick and Reginald Williams, “The Voices of Single Parent Mothers Who are Homeless: Implications for Early Childhood Professionals,” Early Childhood Education Journal 38, no. 1 (2010): 49–55.

7 Ralph de Costa Nunez and Matthew Adams, “Primary Stakeholders’ Perspectives on Services for Families without Homes,” in Supporting Homeless Families: Current Practices and Future Directions, ed. Mary E. Haskett, Staci Perlman, and Beryl Ann Cowan (New York: Springer, 2014): 209–32.

8 Charles L. Baum II, “A Dynamic Analysis of the Effect of Child Care Costs on the Work Decisions of Low-income Mothers with Infants,” Demography 39, no. 1 (2002): 139–64; David Blau and Erdal Tekin, “The Determinants and Consequences of Child Care Subsidies for Single Mothers in the USA,” Journal of Population Economics 20, no. 4 (2007): 719–41; Haksoon Ahn, “Child Care Subsidy, Child Care Costs, and Employment of Low-income Single Mothers,” Children and Youth Services Review 34, no. 2 (2012): 379–87; Jay Bainbridge, Marcia K. Meyers, and Jane Waldfogel, “Child Care Policy Reform and the Employment of Single Mothers,” Social Science Quarterly 84, no. 4 (2003): 771–91.

9 April Crawford, “The Impact of Child Care Subsidies on Single Mothers’ Work Effort,” Review of Policy Research 23, no. 3 (2006): 699–711; Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago, Child Care Subsidy Use and Employment Outcomes of TANF Mothers During the Early Years of Welfare Reform: A Three-state Study, 2004; Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago, Employment Outcomes for Low-income Families Receiving Child Care Subsidies in Illinois, Maryland, and Texas, August 2009; Fred Brooks, “Impacts of Child Care Subsidies on Family and Child Well-being,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17, no. 4 (2002): 498–511; Nicole Forry, Paula Daneri, and Grace Howarth, “Child Care Subsidy Literature Review: OPRE Brief 2013–60,” December 2013

10 Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, Profiles of Risk: Child Care, 2012.

11 Anna D. Johnson, Anne Martin, and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, “Who Uses Child Care Subsidies? Comparing Recipients to Eligible Non-recipients on Family Background Characteristics and Child Care Preferences,” Children and Youth Services Review 33, no. 7 (2011): 1072–83; Fred Brooks, “Impacts of Child Care Subsidies on Family and Child Well-being,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17, no. 4 (2002): 498–511.

12 Child Care Aware of America, Parents and the High Cost of Child Care: 2013 Report.

13 Calculation of average monthly copayment as a percent of family income excludes families with $0 income, families categorized as needing “protective services” or headed by children, and families with invalid income or copayment; Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, FY 2012 CCDF Data Tables (Preliminary Estimates, October 2013); U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “2014 Poverty Guidelines,” http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/14poverty.cfm.

14 Urban Institute, How Contextual Constraints Affect Low-income Working Parents’ Child Care Choices, February 2012; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Study of Child Care for Low-income Families: Patterns of Child Care Use Among Low-income Families, Final Report, 2007.

15 Urban Institute, How Contextual Constraints Affect Low-income Working Parents’ Child Care Choices, February 2012.

16 Anne B. Shlay, Marsha Weinraub, Michelle Harmon, and Henry Tran, “Barriers to Subsidies: Why Low-income Families Do Not Use Child Care Subsidies,” Social Science Research 33, no. 1 (2004): 134–57.

17 Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, FY 2012 CCDF Data Tables (Preliminary Estimates, October 2013).

18 Child Care and Development Block Grant Act of 1990, Public Law 101–508, U.S. Code 42 (1990), § 9858 et seq.

19 Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Estimates of Child Care Eligibility and Receipt for Fiscal Year 2006.

20 For the purposes of this report, the term “states” in this context refers to the governmental entity at the state level that is responsible for designing and implementing the child care subsidy program within that state.

21 With the exception of Alaska, for which only a draft of the state plan was available, the state plans analyzed were the final and current versions, approved by HHS during the fall of 2013.

22 Funded by the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation at HHS, the CCDF Policies Database is maintained by the Urban Institute; Urban Institute, The CCDF Policies Database Book of Tables, 2013.

23 Massachusetts gives certain priority populations, including homeless families, up to six months to provide necessary medical records; Massachusetts Department of Early Education and Care, Policy Statement: Children’s Records Requirements for Priority Populations, September 2010.

24 Debra J. Rog, C. Scott Holupka, and Lisa C. Patton, Characteristics and Dynamics of Homeless Families with Children: Final Report to the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Human Services Policy, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2007.

25 Ibid.

26 Calculation of average monthly copayment as a percent of family income excludes families with $0 income, families categorized as needing “protective services” or headed by children, and families with invalid income or copayment; Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, FY 2012 CCDF Data Tables (Preliminary Estimates, October 2013); ICPH analysis of Fiscal Years 2014–15 Child Care and Development Fund state plans.

27 Center for Law and Social Policy, Scrambling for Stability: The Challenges of Job Schedule Volatility and Child Care, March 2014; Urban Institute, A Summary of Research on How CCDF Policies Affect Providers, March 2012.

28 A proposed rule from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services would amend CCDF regulations to require states to schedule redetermination no sooner than 12 months after the last eligibility determination; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) Program: Proposed Rule,” Federal Register 78, no. 97 (May 2013): 29, 442–98.

29 The exceptions are Connecticut, where eligibility redetermination is scheduled to happen after eight months, and Arkansas, which did not specify the length of its redetermination period in its plan.

30 Improving Head Start for School Readiness Act of 2007, Public Law 110–134, U.S. Code 42 (2007), § 9840.

31 As of June 2014, the U.S. Senate had passed the Child Care and Development Block Grant Act of 2014. The program was last authorized in 1996 and has not undergone significant review since 1998.

32 Massachusetts and Washington describe having done this in their state plans.

33 States are currently required to spend no less than 4% of their CCDF funding on quality improvement activities; Child Care and Development Block Grant Act of 1990.