July 2018

For students living in temporary housing, positive mental health—composed of factors including the ability to cope with stress, connect with others, and maintain good physical health—is often difficult to achieve. Housing instability compounds the stressors in these students’ lives and can lead to overwhelming feelings of sadness or isolation. The lack of a quiet place to unwind, insufficient sleep, and bullying from classmates can take an emotional and psychological toll, and students may resort to harmful actions such as self-injury or suicide. Each year, more than 150,000 youth nationwide are treated in emergency care for self-inflicted injuries. Overall, one in twelve high school students have attempted suicide.

This report, based on data from eight states and New York City,* shows that homeless students are at significantly higher risk for suicide than high school students overall. Their academic success requires ongoing and available support and resources to help them manage the stressors in their daily lives.

Homeless students attempted suicide at

3x to 6x the rate of housed students.

Key Findings

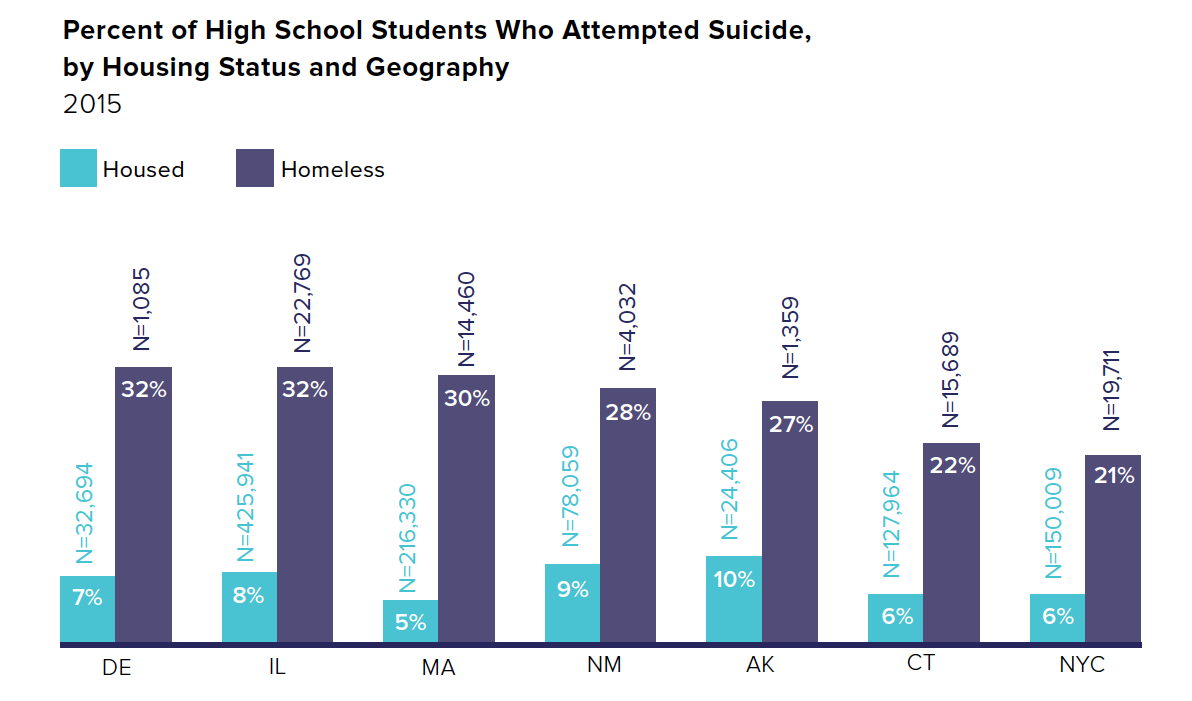

- At least one in five homeless students reported attempting suicide in the previous 12 months (2015), with some states reporting up to one in three. This was compared to less than one in ten housed students.

- Homeless students in Delaware and Illinois had the highest suicide attempt rates (32%), while Massachusetts showed the greatest disparity in suicide attempt rate between homeless and housed students (6x higher).

- Homeless students who were bullied were significantly more likely to report depression than housed students who were bullied (63% to 49%).

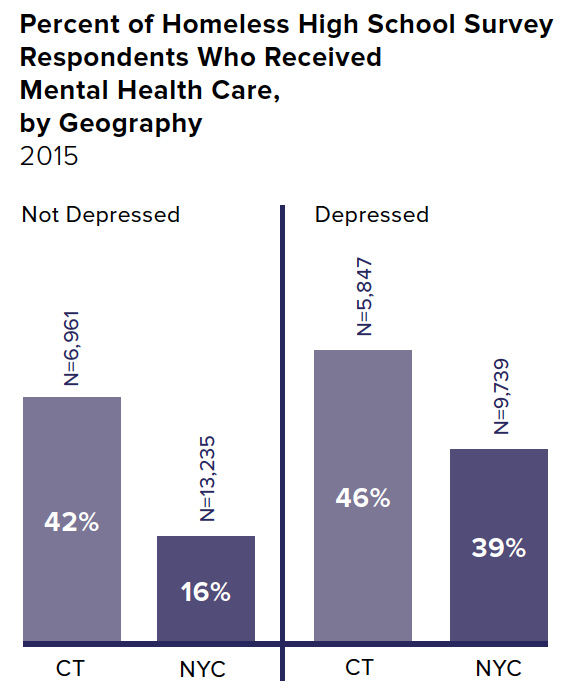

- Homeless students often do not receive mental health care. Fewer than half of homeless teens in Connecticut and New York City who reported depression saw a mental health professional.

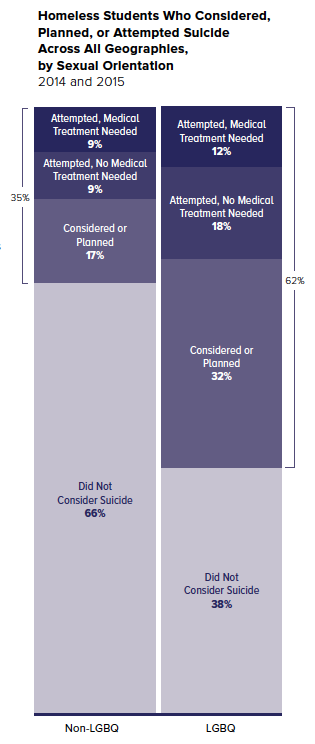

- Homeless students who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or questioning (LGBQ) were nearly twice as likely to consider, plan, or attempt suicide as other homeless students (62% to 34%).

Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS)

Data from this brief are self-reported from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey. The CDC and its partners in state and local health and education agencies are on the front line in collecting data to understand the risks faced by homeless high school students across the country. The national Youth Risk Behavior Survey monitors priority health risk behaviors that contribute to the leading health and social issues in the United States. In 2015, eight states and a handful of cities asked students about their housing status. The subsequent 2017 survey collected data from 19 states. Any state or city may proactively collect information from students experiencing homelessness in their schools by simply electing to add the CDC’s standard housing question to the YRBS. For more information, contact the CDC or your local YRBS partner agency.

*Note: Data from this brief are weighted counts and representative of high school students from 2014-15 YRBS data in Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Mexico, North Carolina, and New York City. Not all surveys asked the same questions, so data are shown where available. “LGBQ” refers to students who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or “not sure” in response to survey questions on sexual orientation. No data was available on students identifying as transgender.

Suicide Attempts Among Homeless Students

Students experiencing homelessness were significantly more likely than housed students to report considering and attempting suicide: by state, more than 20% of homeless students had attempted suicide in the previous 12 months compared to 10% of housed students or less. Nearly one in three homeless students reported attempting suicide in Massachusetts, six times the rate of housed students in that state (30% to 5%).

Suicide attempts among homeless students were also more severe and more likely to result in serious injury requiring medical attention. More than half of the homeless students who attempted suicide reported that they required medical attention afterward, compared to 37% of housed students. These severe attempts often lead to long-lasting mental health effects and physical challenges.

Note: In accordance with CDC conventions, estimates with a 95% confidence interval half-width greater than 10 should be interpreted with caution. In this chart, this includes the percentages for homeless students in Delaware, Illinois, and Alaska.

Understanding a Complete Picture of Mental Health

One method of preventing suicide attempts and severe medical consequences is to identify signs of self-injury, such as cuts or burn marks, and intervene before these behaviors escalate to suicide. Homeless students who injured themselves were more likely to report attempting suicide (51% compared to 30% of homeless students overall).

Even when mental health issues do not lead to suicidal behavior, they cause harm to a student’s mental and physical well-being. Overall, homeless students reported significantly higher rates of depression than housed students (45% to 27%), with more than half of homeless students reporting depression in Maryland and New Mexico (53% and 51%).

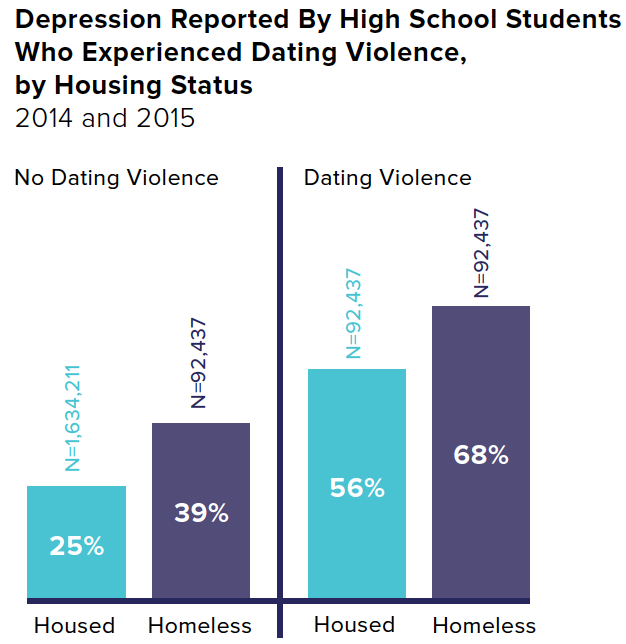

Homeless students who report experiencing dating violence or bullying are at a greater risk of being depressed. Those who experienced dating violence were 1.7 times as likely to report depression as those who did not report dating violence (68% to 39%). Similarly, homeless students who were the victims of bullying were much more likely to report depression as those who were not bullying victims (63% to 34%). Depression can lead to harmful behaviors, such as alcohol and substance abuse. Indeed, homeless students reporting depression were more than twice as likely to binge drink as housed students reporting depression (41% to 19%).

Use of Mental Health Services

Mental health professionals, teachers, and school district homeless liaisons can be critical in recognizing the signs of self-harm and connecting homeless students with the lifelines they need. Even though homeless students have high rates of self-injury and suicidal thoughts and attempts, many cannot access help if they are not able to be diagnosed by a professional. Connecticut and New York City are the only two jurisdictions with YRBS data on mental health services.

These data indicate that when accessible, mental health services are being used by students who need them. In Connecticut, nearly one in two homeless students reported seeing a mental health professional, whether or not they reported depression (46% and 42%). Rates of seeing a mental health professional were lower in New York City than in Connecticut, but were more than twice as high for homeless students who reported feeling depressed (39%) as those who did not report depression (16%).

Suicidal Behavior Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, or Questioning Homeless Youth

Homeless students who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or questioning (LGBQ) were nearly twice as likely to report considering or attempting suicide as non-LGBQ homeless students (62% to 34%). Bullying from classmates and lack of acceptance from family members can create or worsen feelings of isolation and depression. Among homeless LGBQ students, those who were bullied reported depression at nearly 1.5 times the rate of those who were not bullying victims (68% to 47%).

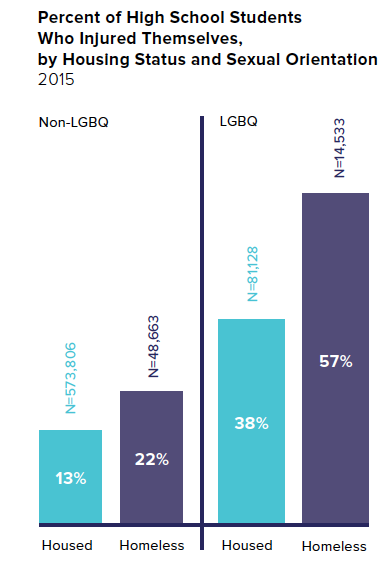

Homeless students who identify as LGBQ are at the greatest risk of self-injury, with 57% of them reporting deliberately hurting themselves in the previous 12 months. This was 2.6 times the rate of homeless non-LGBQ teenagers and 4.4 times the rate of housed non-LGBQ students (57%, 22%, and 13%).

Policy Considerations

- Increase availability of mental health care services at schools. Homeless students are more likely to use school-based health services than housed students. Yet in New York City, only 33% of high schools have School-Based Health Centers. Departments of Education should consider these data when planning school supports needed for students struggling with mental health. On-site services that are free and accessible can help homeless students effectively manage their stress. In addition, the integration of mental health in schools’ health education curriculum would help to destigmatize mental illness and educate students about healthy ways to deal with their emotions.

- Incorporate trauma-informed care into teacher and school staff trainings. Teachers and other school personnel should be aware of the signs of depression and suicidal behavior, with an attentiveness to self-injury as a potential precursor to suicide. Trauma-informed strategies can help teachers to identify signs of mental health problems among students and refer them to available support services.

- Target services to homeless LGBQ students. Mental health services and outreach should include the specific needs of homeless LGBQ students, who are critically at risk for suicidal behavior. Teachers often already know which students have been bullied and are most in need of additional support. Schools that already offer on-site mental health care should evaluate their capacity for working with students experiencing homelessness and LGBQ students.

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, President and CEO

Aurora Zepeda, Chief Operating Officer

Katie Linek Puello, Digital Communications Manager

Project Team:

Anna Shaw-Amoah, Principal Policy Analyst

Amanda Ragnauth, Senior Policy Analyst

Kaitlin Greer, Policy Analyst

Rachel Barth, Policy Analyst

Marcela Szwarc, Graphic Designer

Hellen Gaudence, Graphic Designer