Introduction

To the over 360,000 high school students who experience homelessness every year, school is often the only constant in their otherwise highly mobile and unpredictable lives.1 The many struggles that often accompany housing instability, such as physical and mental health issues, sleep deprivation, hunger, sexual violence, substance use, chronic absenteeism, and mid-year school transfers, can all have detrimental impacts on the learning and well-being of these students.

Supportive school climates—schools that cultivate connections with students and foster feelings of safety and security—have been proven to enhance academic and mental health outcomes and can help homeless high schoolers overcome the obstacles they face due to housing instability. When homeless students are engaged in academics and extracurriculars, feel safe with teachers and peers, and have a clear sense of school rules and norms, schools are able to serve as the pillar of stability that they need to thrive.

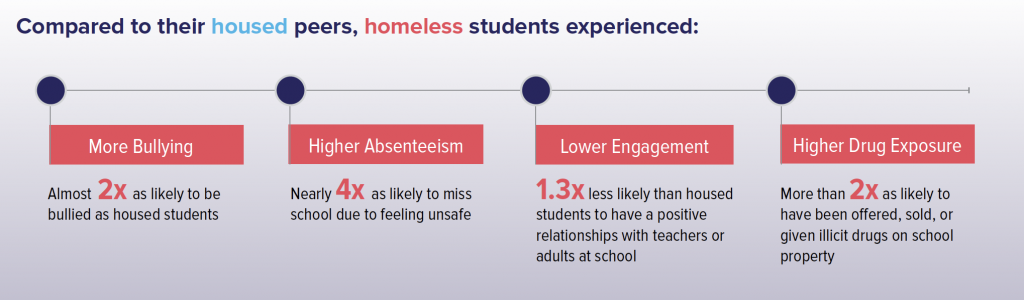

While the benefits of safe and supportive school climates have been well-documented, homeless students are less likely than their housed classmates to report feeling connected to their teachers and peers, more likely to be bullied and feel unsafe at school, and less likely to have a clear sense of school rules and their fair enforcement. Homeless students are also more at risk of experiencing multiple negative school climate factors. Unfortunately, the more of these negative factors that homeless students experience, the less likely they are to achieve academically and continue their educations post-high school, and the greater their likelihood of suffering from depression and even attempting suicide.

While each of these areas are important on their own, they overlap and intersect in complex ways. Using weighted estimates of self-reported data from the 2016–17 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, Part I of this report explores each of these areas separately. Part II analyzes the cumulative impact of these school climate indicators on the academic and mental health outcomes of homeless high school students.

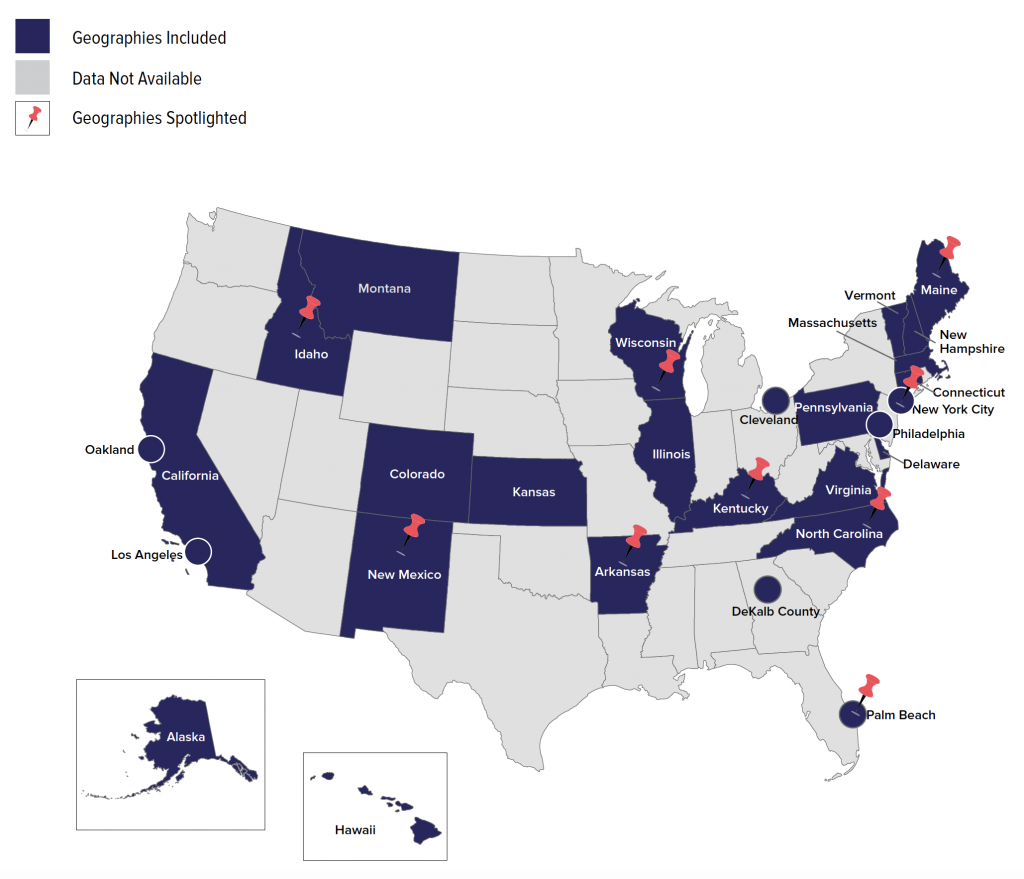

Geographies Included in Analysis of School Climate

Note: Questions asked in five or more locales were combined into pooled indicators. For a complete list of which geographies were included in each chart, visit https://www.icphusa.org/SchoolClimateNotes. If a question was asked by fewer than five locales, a spotlight of the results from just one geography is shown.

Part I

1.0 Measuring Perceptions of School Climate Among Homeless Students

School climate encompasses a wide range of factors that work together to shape a student’s learning and social-emotional development.

Based on the Safe and Supportive Schools Model, there are three key dimensions of school climate:

1.1 Engagement

1.2 Safety

1.3 Environment

1.1 Engagement

School engagement refers to feeling connected to the school through participation in academic and extracurricular activities, and positive relationships with staff and peers.

Although school engagement is important for homeless students who may feel otherwise disconnected from other adults and institutions, they reported receiving lower grades and were less likely to participate in sports or other extracurricular activities than their housed peers. Homeless high school students were also less likely to feel connected to teachers and to feel a sense of belonging at their schools.

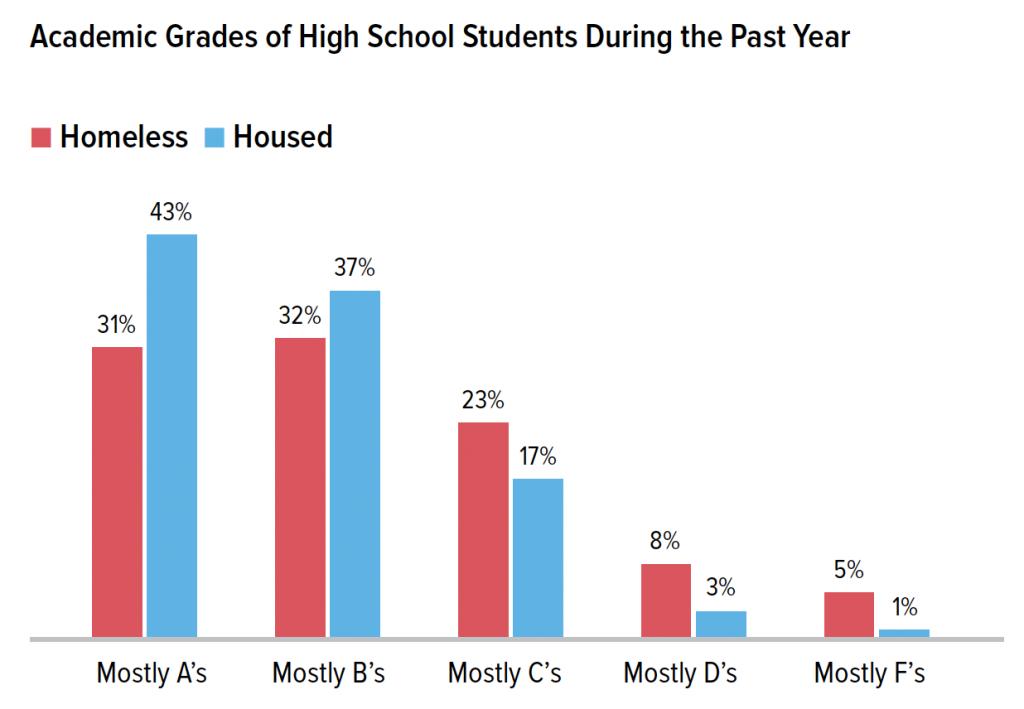

How Do Homeless Students Perform in School?

Nearly two-thirds of homeless students (63%) got mostly A’s or mostly B’s, but homeless students were still less likely than housed students (80%) to get these grades. Homeless students were about 1.7 times more likely than housed students to get mostly C’s, D’s, or F’s (36% vs. 21%). Although grades are not the only measure of a student’s success in school, homeless students’ poor grades could indicate disengagement, lack of a quiet place or proper resources to complete homework, or chronic absenteeism.

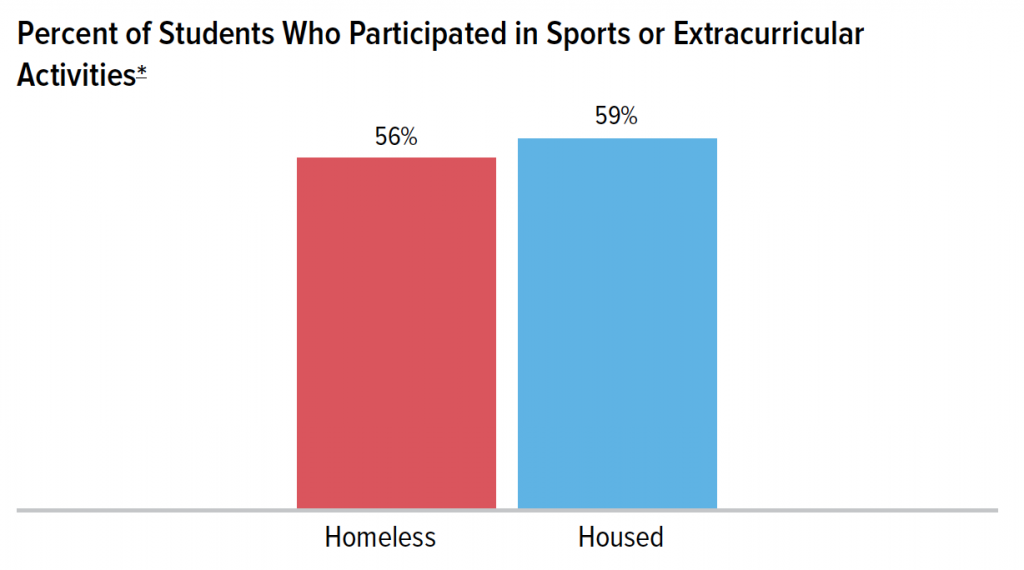

Are Homeless Students Involved in School Activities?

In addition to academics, involvement in sports and other extracurricular activities can help keep teens physically active and connected to their peers, teachers, and schools. Homeless students were only slightly less likely than housed students to be involved in sports or extracurricular activities (56% vs. 59%).

Schools that offer sports and other activities that are easily accessible for homeless students create opportunities for these students to stay connected, involved, and have a safe place to be after school. The benefits of extracurriculars are important for all students, but the added stability and sense of belonging can be crucial for students experiencing homelessness, who might have more difficulty accessing activities outside of school.

The relatively high participation among homeless students in

extracurriculars may be due to the McKinney-Vento Act, which

allows students to participate in activities without necessary

documentation, and may help students secure funds for

participation in sports and other activities.3

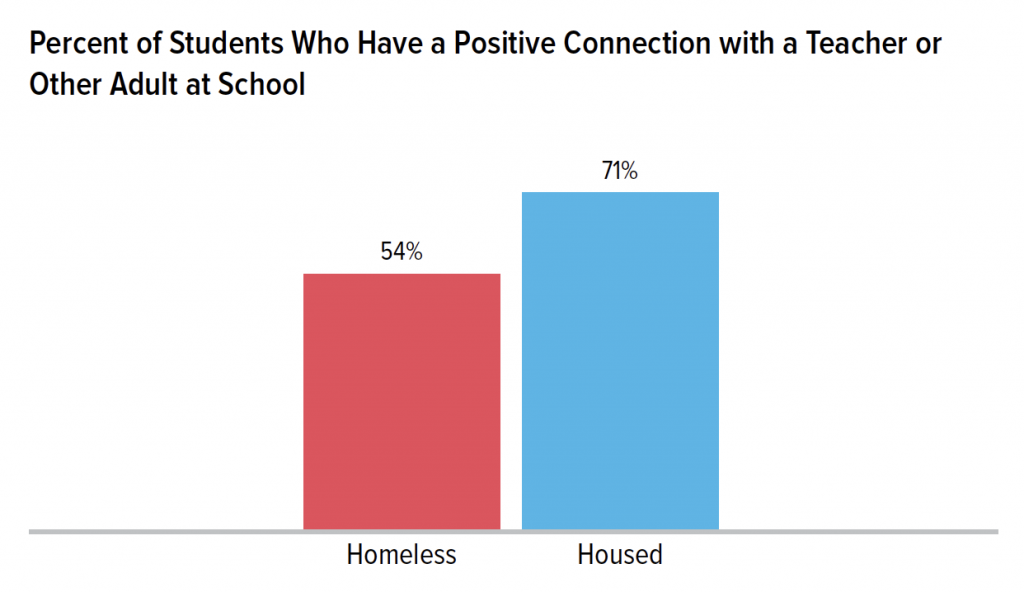

Do Homeless Students Feel Connected to Teachers and Other School Staff?

Over half of homeless students (54%) said they had a positive connection with a teacher or other adult at school, about 1.3 times lower than housed students (71%).

While positive relationships with teachers and other adults at school are important for all students, the sense of community that this connection can provide for homeless students is vital. Without this relationship, homeless students might not have any other adult they can turn to for help or emotional support outside their families.

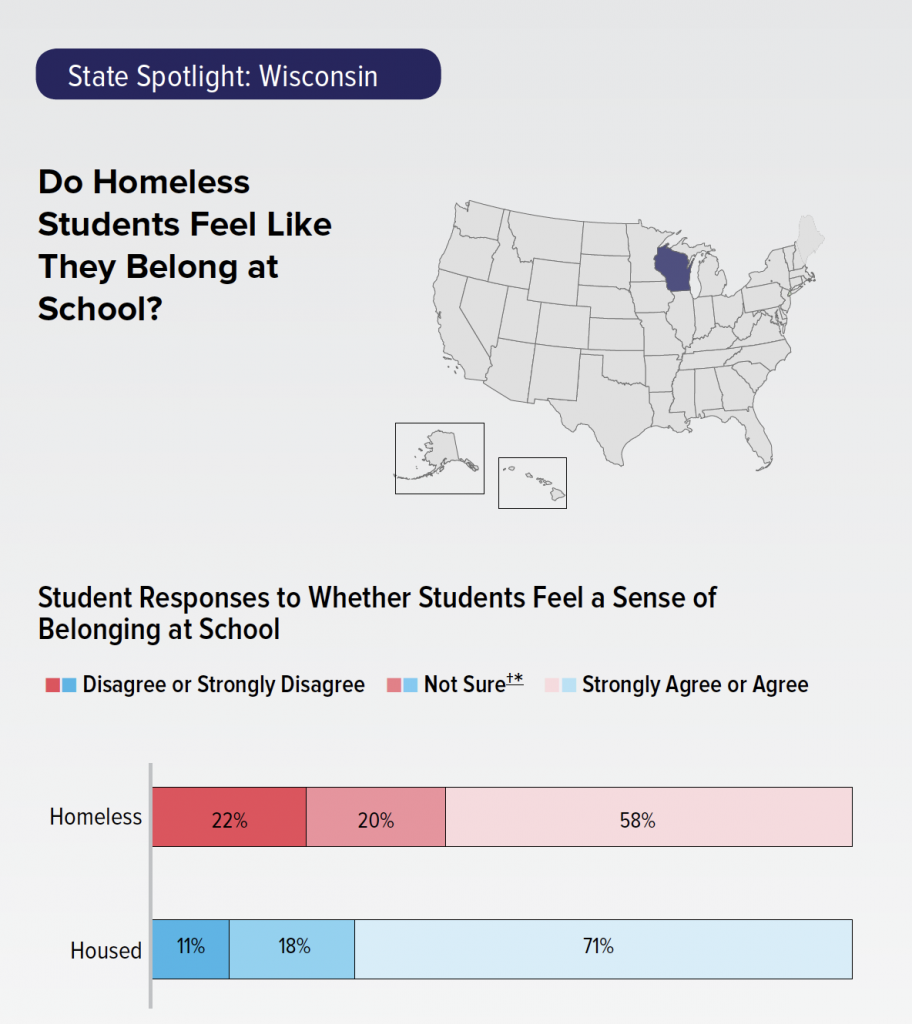

While the majority of homeless students in Wisconsin (58%) feel a sense of belonging at school, homeless students were twice as likely as housed students to feel like they did not belong (22% vs. 11%). Lacking a sense of belonging at school can be caused by or lead to disengagement with teachers and peers, exacerbating other common challenges among homeless students like bullying and depression.

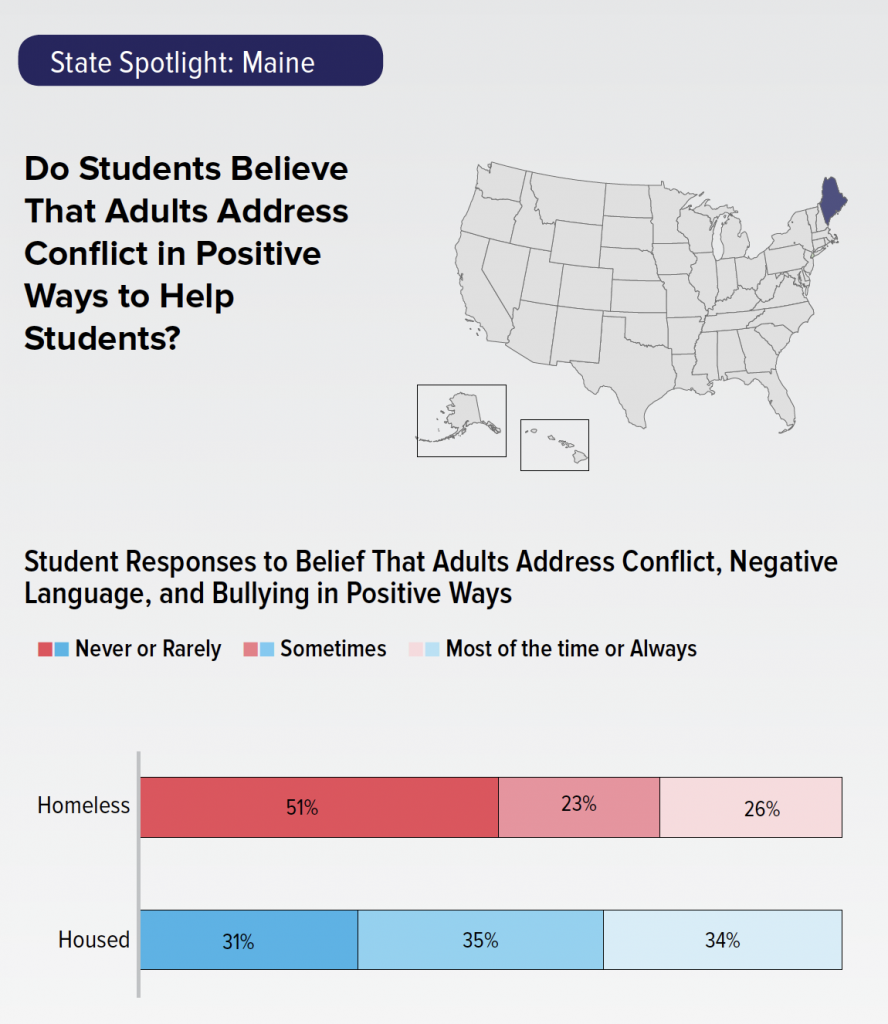

Over half (51%) of homeless students in Maine said that adults never or rarely address conflict, negative language, and bullying in positive ways to help students. When teachers can identify homeless students and acknowledge the factors that might lead to conflict involving homeless students, they can more effectively intervene when conflict arises.

1.2 Safety

School safety means that students are free from concerns of bullying, harassment, and violence at school.

When students feel safe at school, they are more likely to attend classes regularly and are able to focus on learning and building supportive social networks. Feeling unsafe at school cultivates distrust and perpetuates violent behaviors, hindering social-emotional development and academic success.

For students experiencing housing instability, it is crucial that schools represent havens of safety and security. Yet homeless students are more likely to experience unsafe school environments than their housed classmates. They reported being bullied and missing school because they felt unsafe at higher rates than housed students. They were also more likely to report getting into fights, being threatened, and carrying a weapon in school.

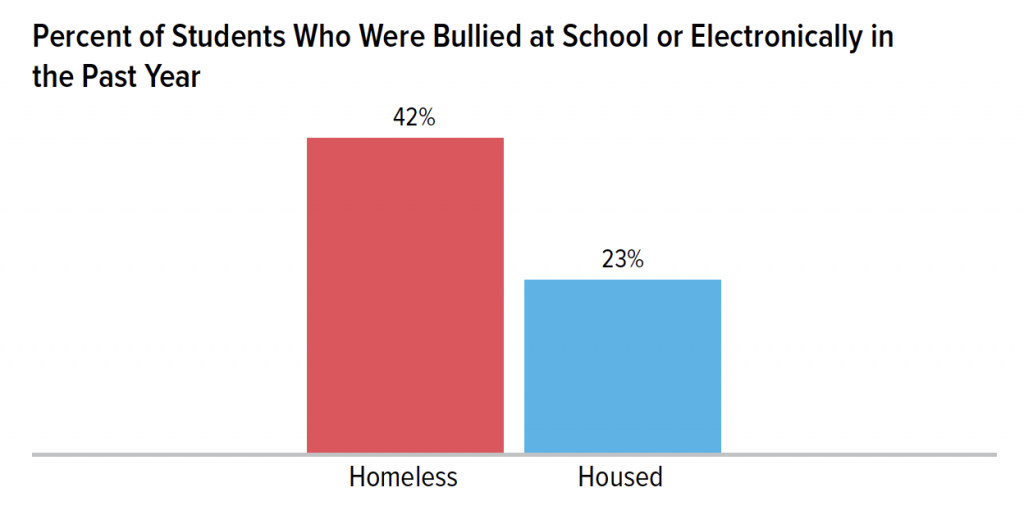

Are Homeless Students More Likely to Be Bullied than Housed Students?

Homeless students were bullied at school or electronically at nearly twice the rate of housed students (42% vs. 23%).

Homeless students often get bullied because of their housing status or related reasons, like not having clean clothes or access to a shower.4

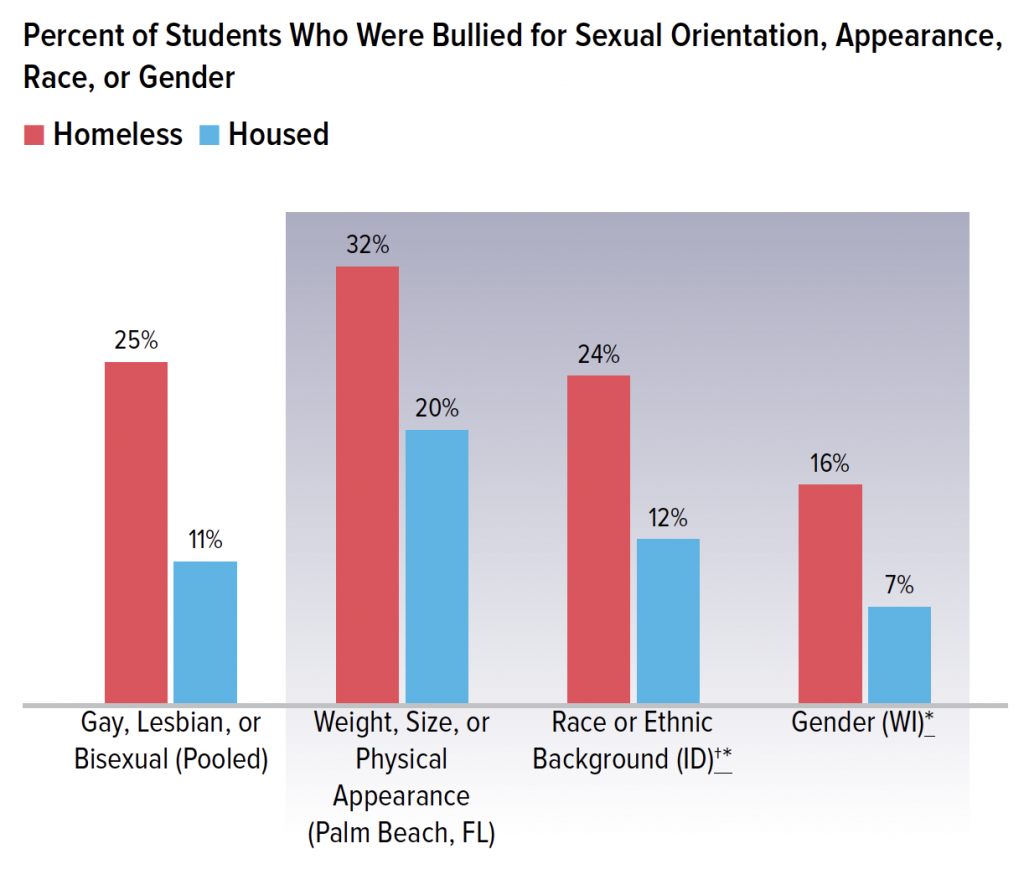

What Are Some Reasons Why Homeless Students Are Bullied?

Homeless students were also more likely to be bullied for their identity, whether it be sexual, physical, racial, or gender-related. Students that experienced homelessness were more likely than housed students to identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual and more likely to be bullied because of this. One-quarter (25%) of homeless students were bullied because someone thought they were gay, lesbian, or bisexual, over two times the rate of housed students (11%).

In locales that included other questions regarding identity bullying, homeless students were more likely to report being bullied due to their appearance, race, or gender. One in three (32%) homeless students in Palm Beach, FL were bullied due to their physical appearance, compared to one in five (20%) housed students. Meanwhile, homeless students in Idaho were twice as likely as their housed peers to report being bullied because of their race or ethnicity (24% vs. 12%), and homeless students in Wisconsin were over twice as likely to be bullied because of their gender (16% vs. 7%).

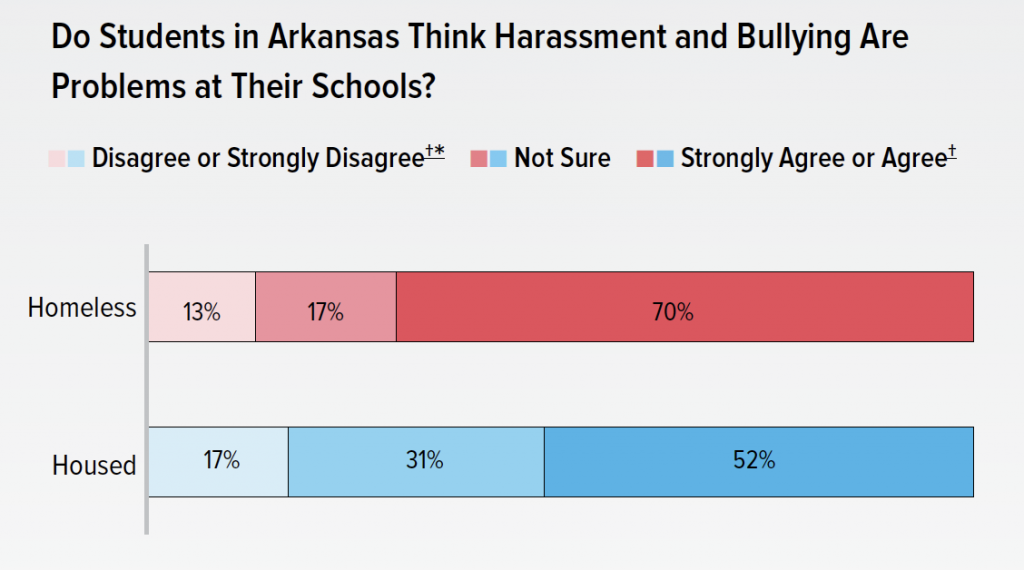

In Arkansas, 70% of homeless students said harassment and bullying are problems at their schools, compared to 52% of housed students.

The presence of harassment and bullying at school creates an uncomfortable environment for all students, regardless of housing status or whether they have been victims of bullying themselves. It is important to address bullying before it becomes an impediment to students’ learning and well-being.

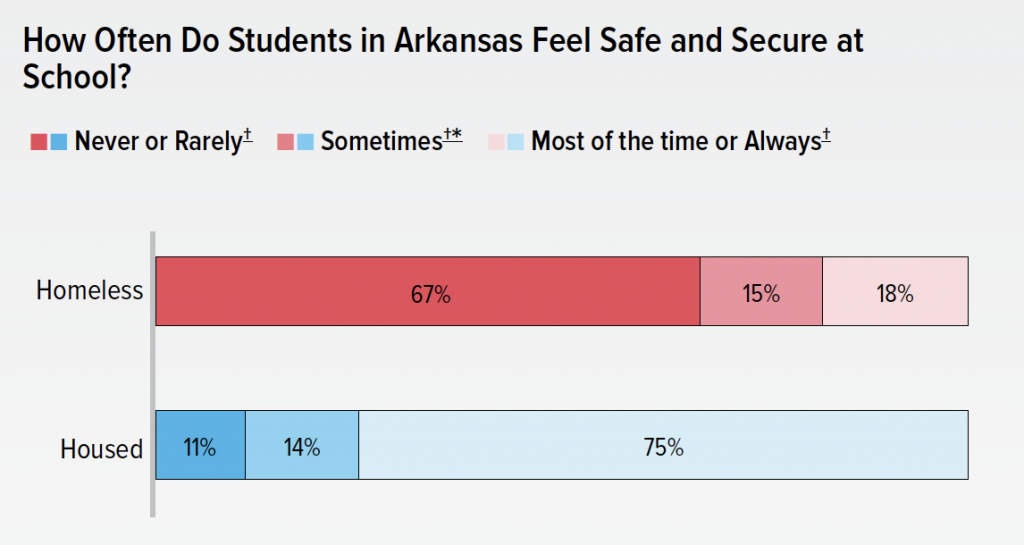

Homeless students in Arkansas were also much less likely to feel safe and secure at school. Over two-thirds (67%) of homeless students said they never or rarely felt safe and secure at school, compared to just 11% of housed students.

What Happens When Students Do Not Feel Safe at School?

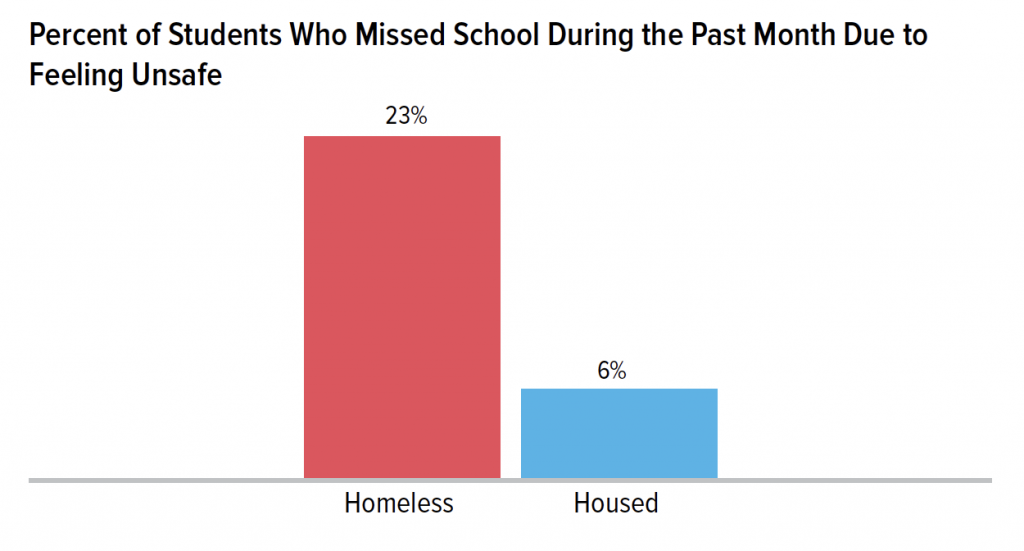

Nearly one-quarter (23%) of homeless high schoolers missed school in the past month because they felt unsafe on their way to, from, or at school—nearly four times the rate of housed students (6%).

Chronic absenteeism is already a common occurrence among homeless students due to lack of transportation, sleep deprivation, and general disengagement, among other reasons. Ensuring students feel safe at school could help reduce chronic absenteeism among homeless high schoolers.

Are Homeless Students Experiencing Violence at School?

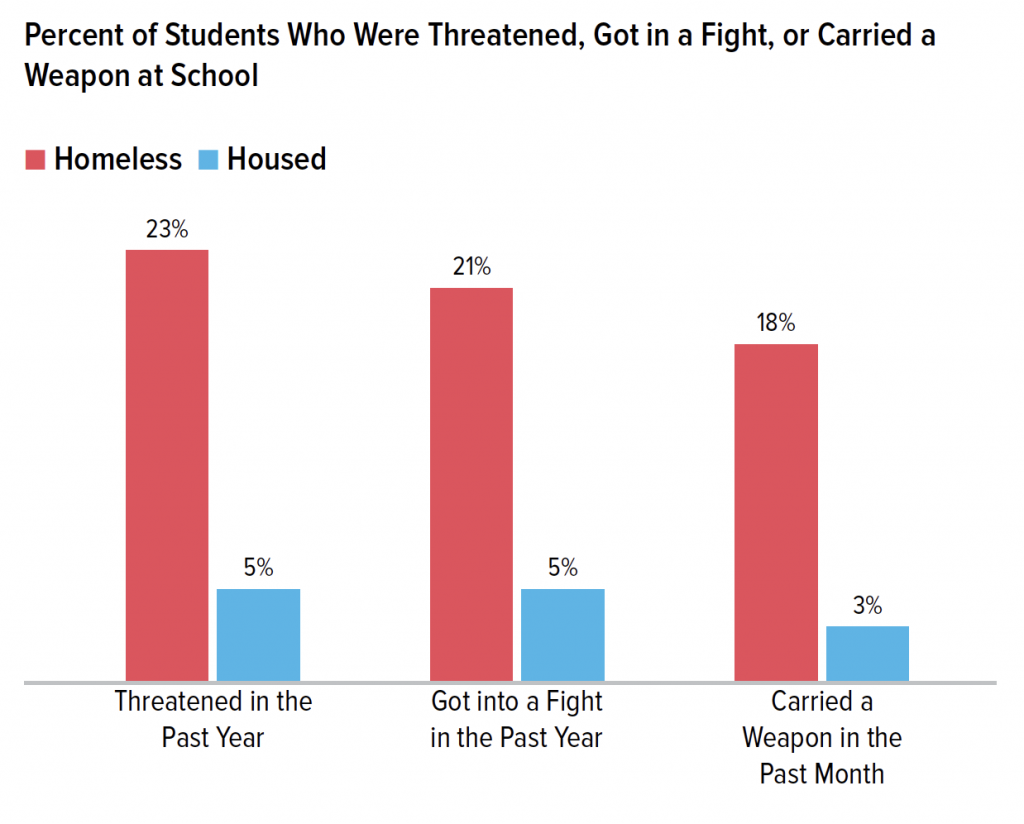

The data on school safety also show that homeless students were more likely to experience violence at school. Nearly one in four homeless students (23%) were threatened at school, and about one in five got into a fight at school (21%).

Additionally, students who experienced homelessness were six times more likely than housed students to carry a weapon at school (18% vs. 3%). While it is clear that homeless students experience higher rates of threats and violence at school, these actions may also be the product of violence experienced in their communities, beyond the confines of school.5

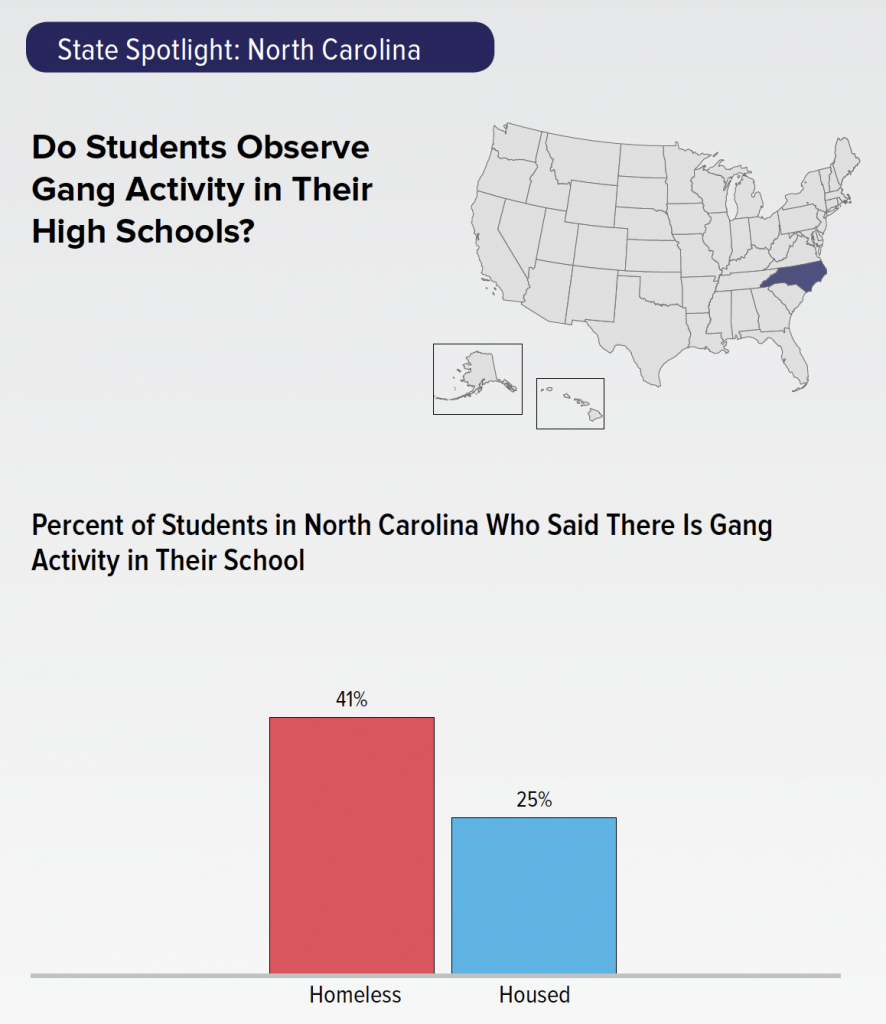

In North Carolina, 41% of homeless students reported gang activity in their schools, more than 1.5 times the rate of housed students (25%).

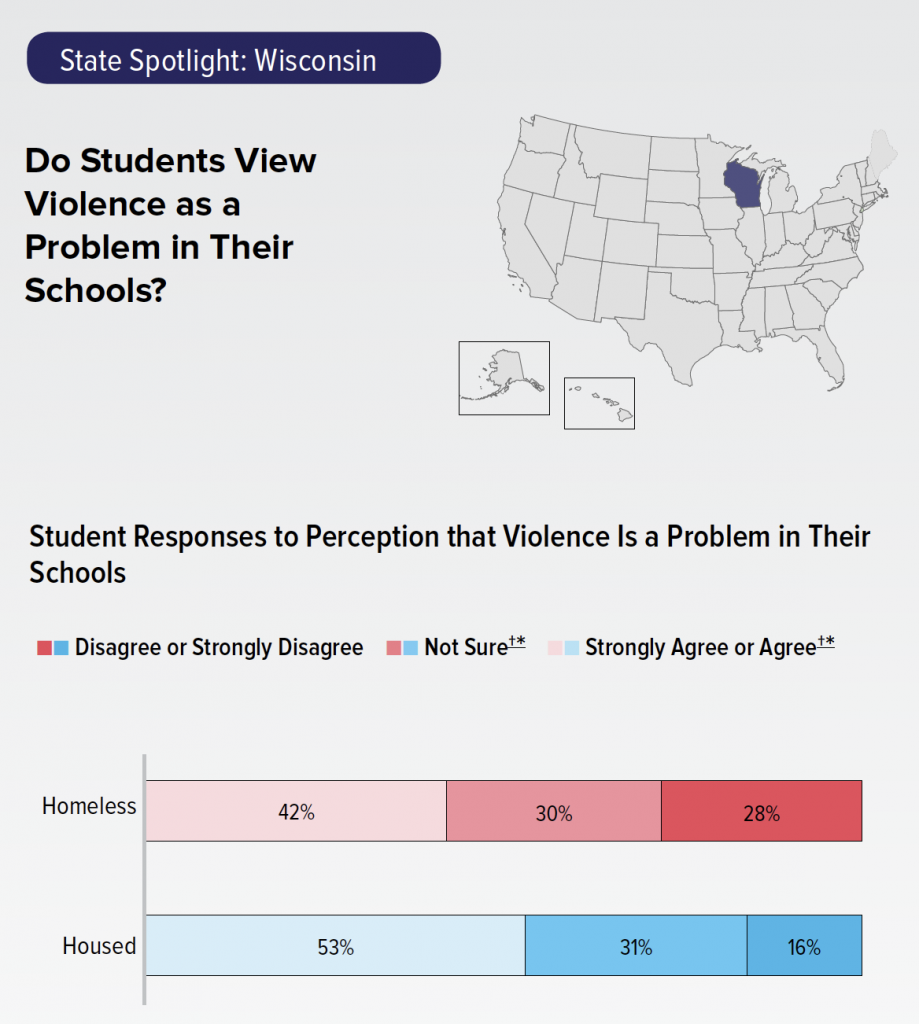

In Wisconsin, 28% of homeless students agreed or strongly agreed that violence is a problem at their school, nearly twice the rate of housed students (16%).

1.3 Environment

School environment refers to exposure to drugs and alcohol at school, clear and fair rules, and school-based health supports.

A positive school environment allows students to feel both engaged and safe in their schools. Across most school environment indicators, students who experienced homelessness were more likely to report less favorable school environments.

This includes exposure to and use of drugs in school and a lack of clarity on school rules and their enforcement. However, data show that when school resources like health centers are available, homeless students were more likely to utilize their services than their housed peers—a positive finding given that these students often lack access to these services in non-school settings.

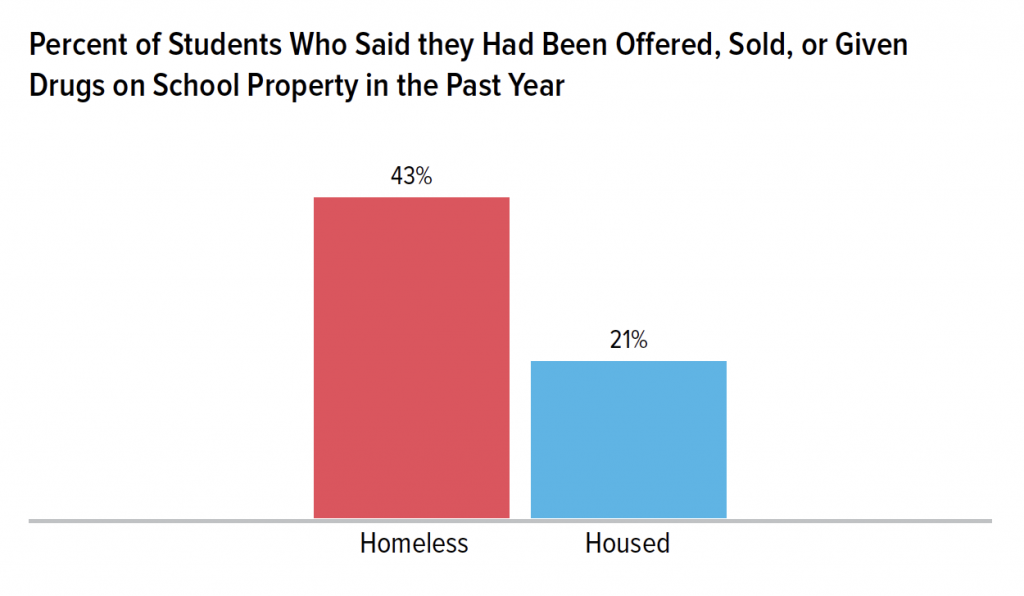

Are Homeless Students More Likely To Be Exposed to Drugs at School?

Homeless students were twice as likely as housed students to have been offered, sold, or given drugs on school property (43% vs. 21%).

Homeless students are more likely to use drugs, and having easy access to them at school makes them harder to avoid.

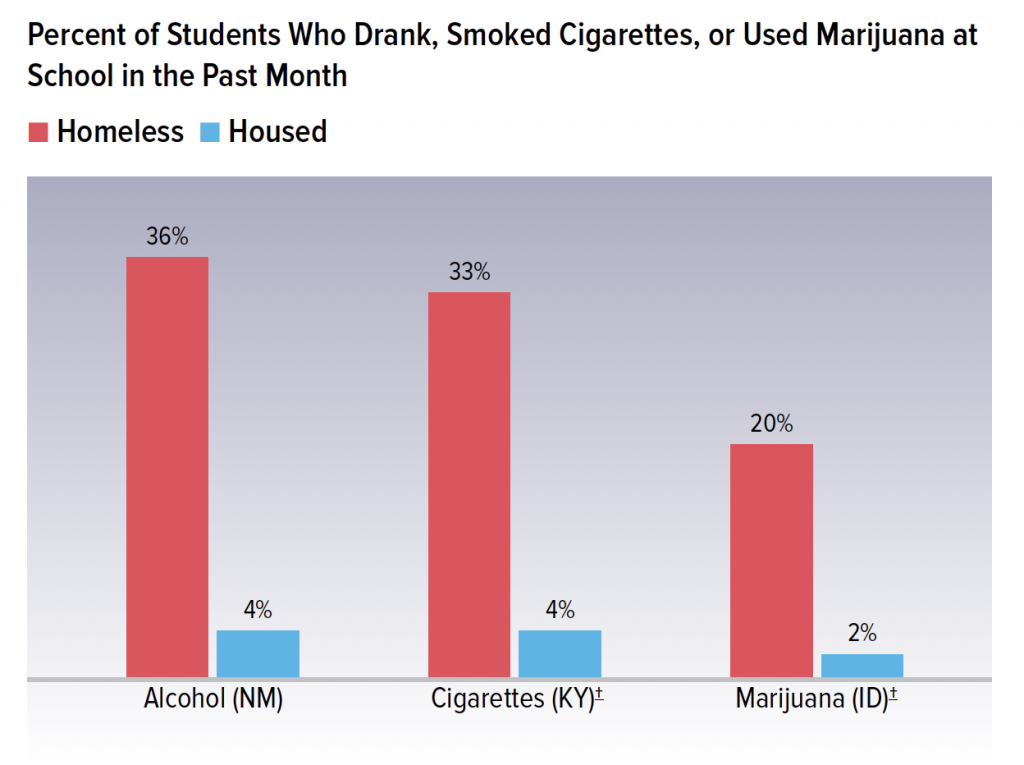

Are Homeless Students More Likely to Drink, Smoke Cigarettes, and Use Marijuana at School?

In states that asked about use of specific substances (alcohol, cigarettes, or marijuana) at school, students that experienced homelessness were also more likely to report using these substances at school than housed students. In New Mexico, homeless students were nine times more likely than housed students to drink alcohol at school (36% vs. 4%), while in Kentucky these students were eight times more likely to smoke cigarettes at school (33% vs. 4%), and in Idaho they were ten times more likely to use marijuana at school (20% vs. 2%).

Underage substance use, whether it is drugs, alcohol, cigarettes, or marijuana, is a problem regardless of where it happens. Substance use can have a negative impact on brain development, the ability to focus and learn, and emotional and physical well-being. In addition, it can lead to serious legal issues and involvement in the criminal justice system.

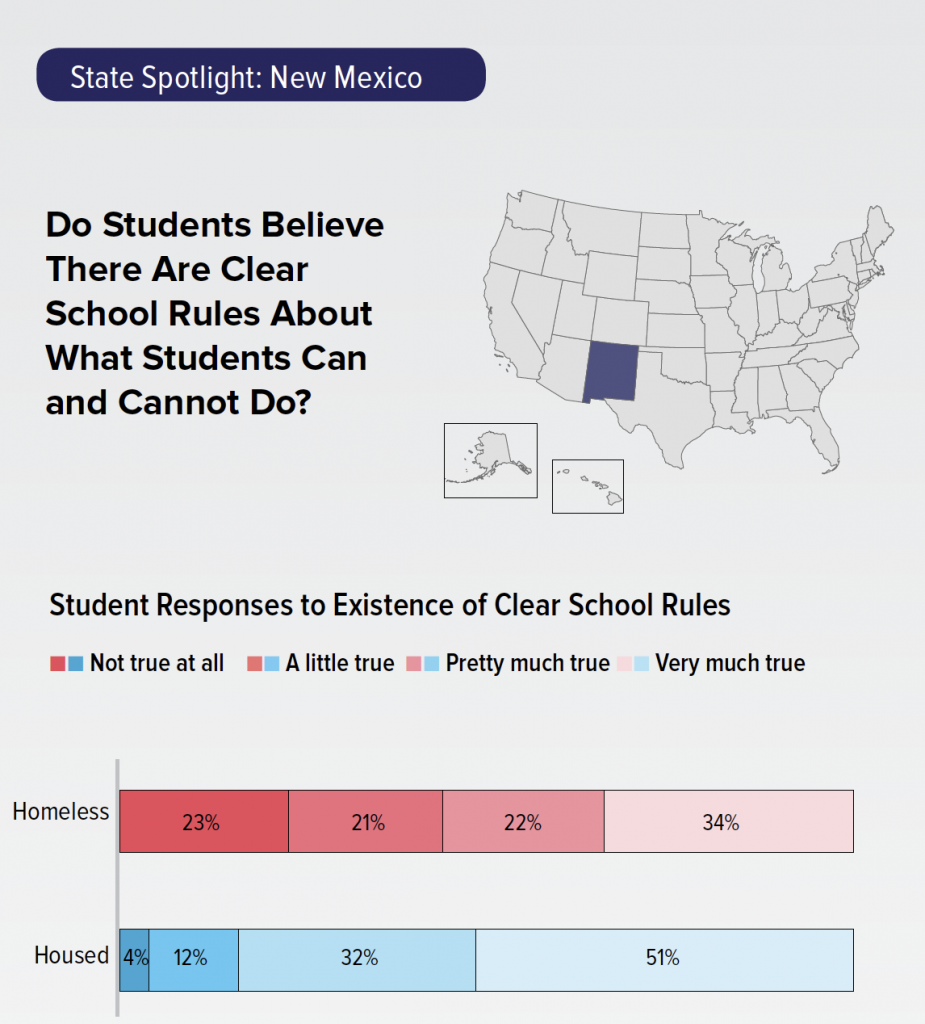

Do Homeless Students Believe Their Schools Have Clear and Fair School Rules?

Another key component of a positive school environment is clear school rules and norms. Students who do not have a clear understanding of expectations for acceptable behavior are more likely to get into trouble and more at risk of being suspended. This can be particularly challenging for homeless students, who already face higher rates of suspension and who may struggle to keep track of school rules and expectations due to frequent school transfers and chronic absenteeism.

Just over one-third of homeless students (34%) in New Mexico said that it was very much true that there were clear school rules—compared to over half of housed students (51%) who responded this way. Conversely, nearly one-quarter of homeless students (23%) said it was not true at all that there were clear rules about what students could and could not do in school, compared to only 4% of housed students who answered so.

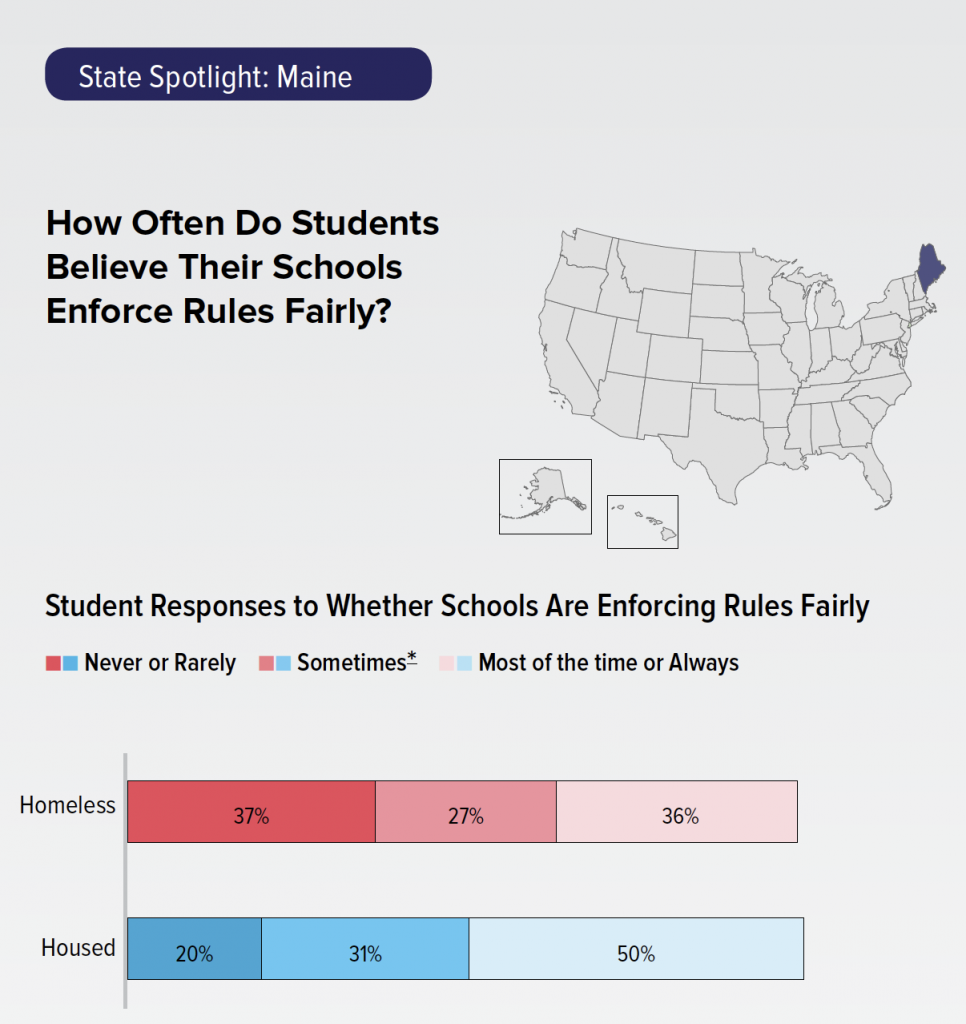

More than one-third (37%) of homeless students in Maine say their school never or rarely enforces rules fairly, compared to 20% of housed students. While rules need to be enforced fairly for all students, understanding the circumstances that might lead to a homeless student breaking a rule, like a uniform violation due to lack of access to laundry, is a necessary component of fair and equitable policy and school environment.

Do Homeless Students Use School Resources?

School environment also includes access to physical and mental health services at school, which are especially important for homeless students who might not have access to these services outside of school. Analysis of the 2015 YRBS in New York City found that homeless students were less likely than housed students to attend schools with school-based health centers, but more likely to use them when they did have access. Currently, New York City is the only locale to ask about both housing status and school-based health services on the YRBS.

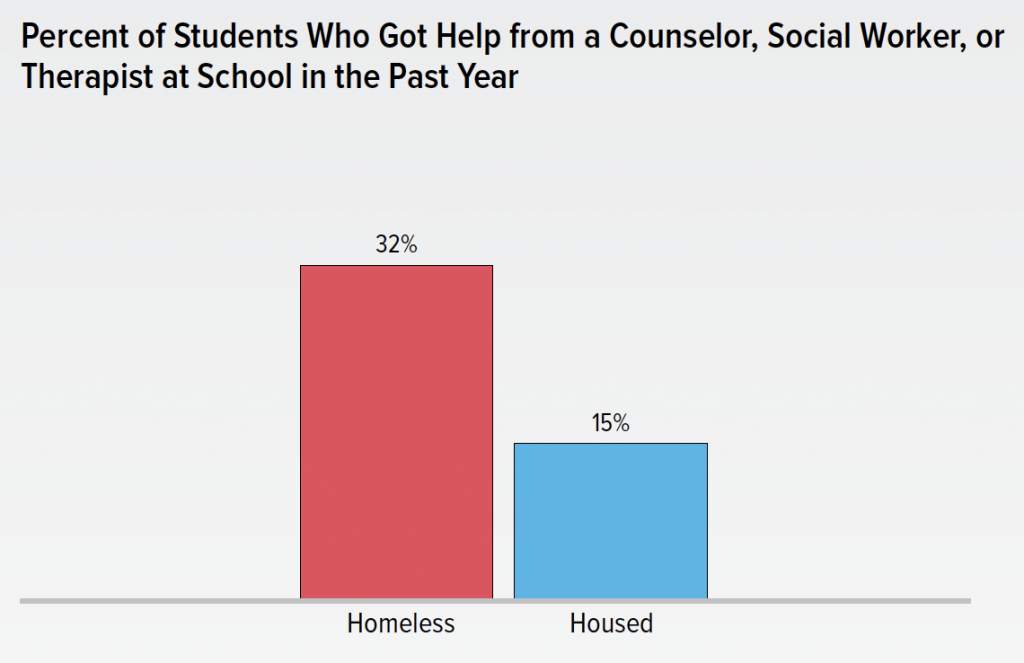

In New York City, 32% of homeless students got help from a counselor, social worker, or therapist at school, over twice the rate of housed students (15%). In addition to having less access to mental health supports outside of school, homeless students are often more in need of these services.

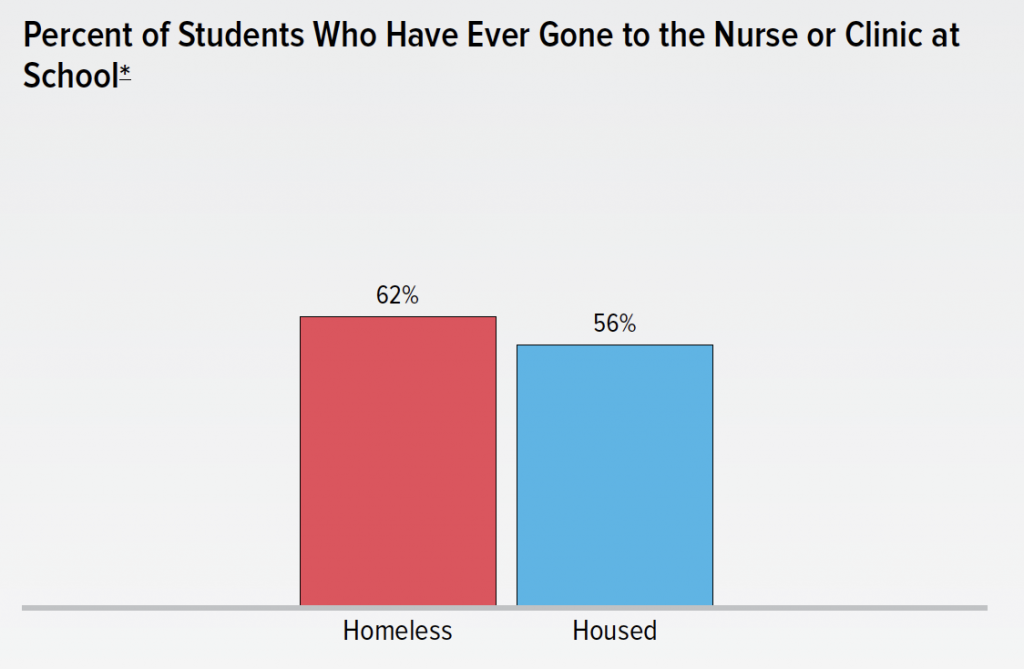

While homeless students in New York City were only slightly more likely than housed students to have ever gone to the nurse or clinic at school (62% vs. 56%), having access to medical services at school is an important component of school environment, as it might be the only opportunity homeless students have to see a doctor or nurse.

Part II

2.0 The Cumulative Impact of Negative School Climate Among Homeless High School Students

When students attend schools with positive school climates—environments that are conducive to students feeling engaged and safe at school—they have higher self-reported GPAs and are less likely to be depressed than their peers at schools with poor school climate. Academic achievement and mental health are already impacted by a student’s housing status, but a positive school climate can help mitigate some of these effects of housing instability. While any one measure of school climate can have an impact on students, homeless students are more likely to experience multiple negative indicators of school climate, and they are more susceptible to their cumulative impact than stably-housed students.

There are many useful and important measures of school climate, but most were not asked widely enough to be used as a measure of the cumulative impact of school climate. As a result, school climate is measured in this section using the following key indicators of school engagement, safety, and environment:

- Bullying

- Missing school due to feeling unsafe

- Lacking positive relationships with teachers or adults at school

- Being offered, sold, or given illicit drugs on school property

If a student experienced all four of these negative indicators (labeled “four” on the charts), they are considered to have a very negative school climate. Conversely, a student who did not experience any of these factors (labeled “zero” on the charts) is considered to have very positive school climate.

For the purpose of this report, all four school climate indicators are given equal weight. In reality, some may have a larger impact on student outcomes than others.

Due to a limited number of geographies including all four of these questions on their surveys, the analysis in this section uses data from: Arkansas, Connecticut, Idaho, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, New Mexico, North Carolina, Vermont, and Wisconsin—just ten of the 28 geographies included in this report. For this reason, overall percentages in this section may differ from percentages presented elsewhere in this report or other ICPH publications.

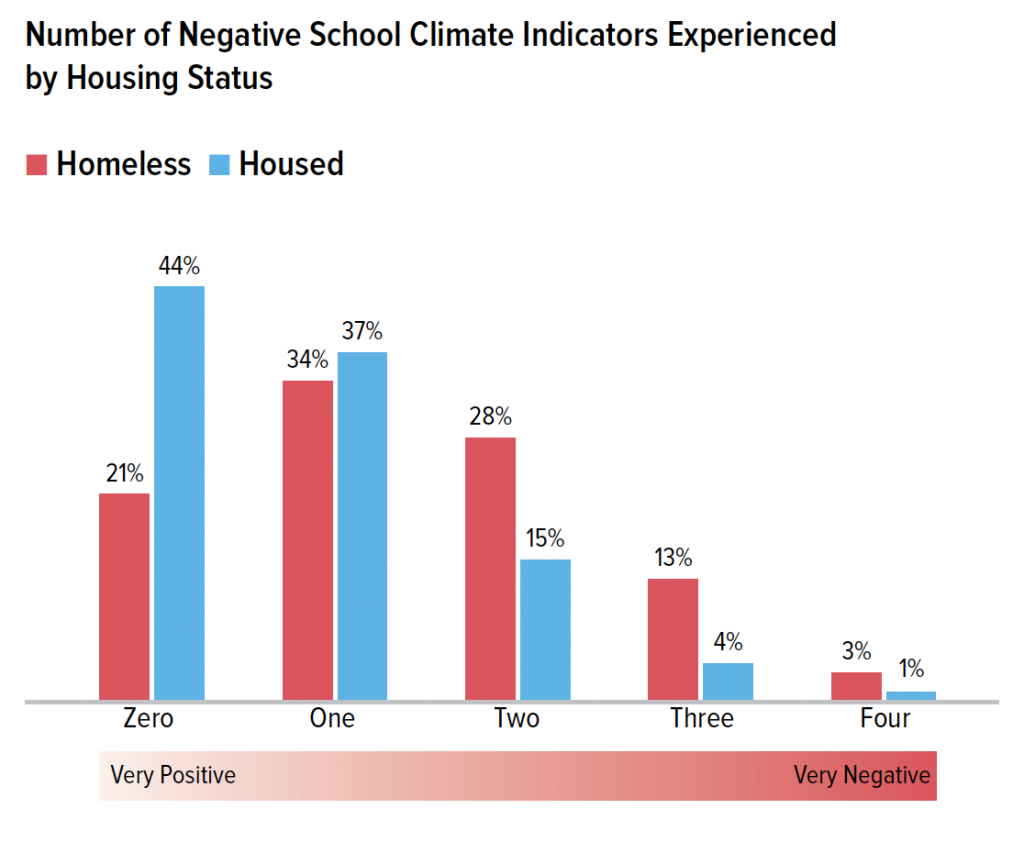

2.1 Homeless Students Disproportionately Experience Negative School Climates

Although more than half of homeless students (55%) experienced just one or no negative school climate indicators, they were still half as likely as housed students to experience no negative school climate indicators (21% vs. 44%). Additionally, homeless students were about four times more likely than housed students to experience three (13% vs. 4%) or four (3% vs. 1%) negative school climate indicators, meaning three times as many homeless students were bullied, missed school because they felt unsafe, lacked positive relationships with adults at school, and were offered, sold, or given drugs at school.

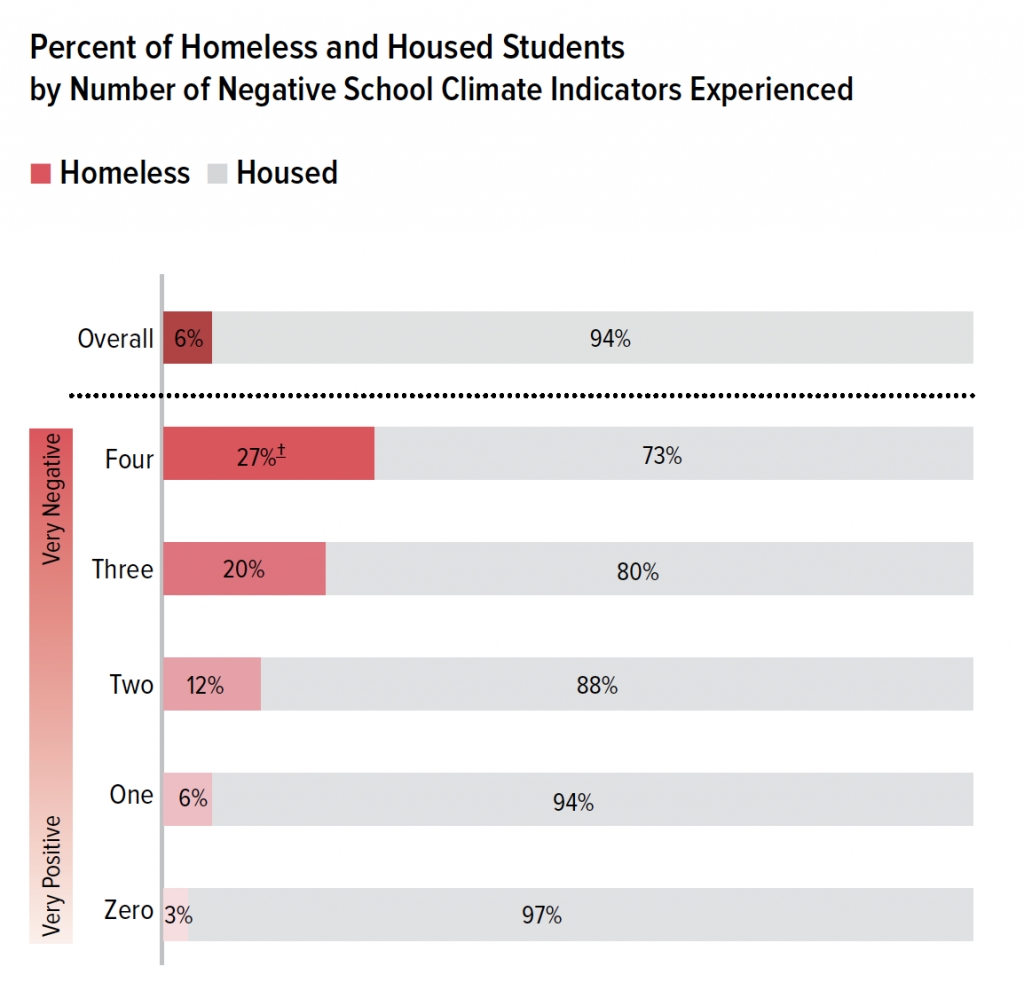

Not only are homeless students more likely than housed students to experience multiple negative school climate indicators, but they are disproportionately represented among students who report multiple indicators.

Only 6% of the students included in these estimates are homeless while 94% are housed; therefore, if homeless and housed students were experiencing school climate indicators equally, about 6% of students in each grouping—from zero to four negative school climate indicators experienced—would be homeless.

However, homeless students are overrepresented among the groups of students who experienced two to four negative school climate factors. Among students who experienced two of these indicators, 12% were homeless—two times the percentage of homeless students in the overall estimates. Among students who experienced three or more indicators, at least 20% were homeless. This is more than three times the proportion of students experiencing homelessness overall. Meanwhile, only 3% of students who perceived the most positive school climates experienced housing instability.

2.2 The Impact of School Climate on Homeless Students’ Academic Outcomes and Mental Health

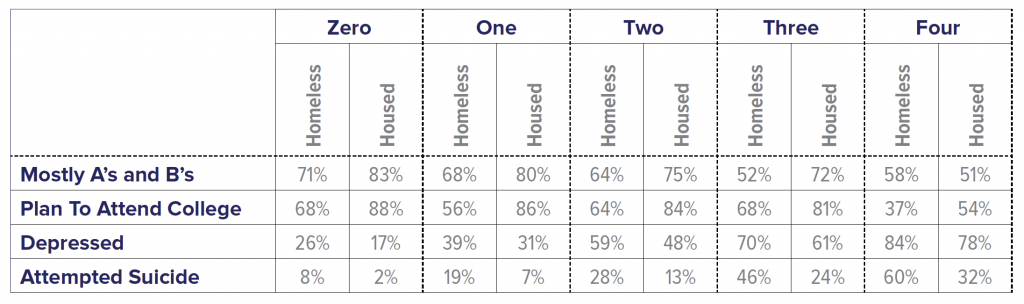

Homeless students face many challenges and often lack access to resources outside of school, making them more vulnerable to the impacts of negative school climate. Overall patterns illustrating the relationship between school climate and academic and mental health outcomes were similar among housed and homeless students. Since negative school climate disproportionately affects homeless students, and homeless students are more likely to have poor academic and mental health outcomes, this section focuses only on the relationship between perception of poor school climate and the academic and mental health outcomes of homeless students.

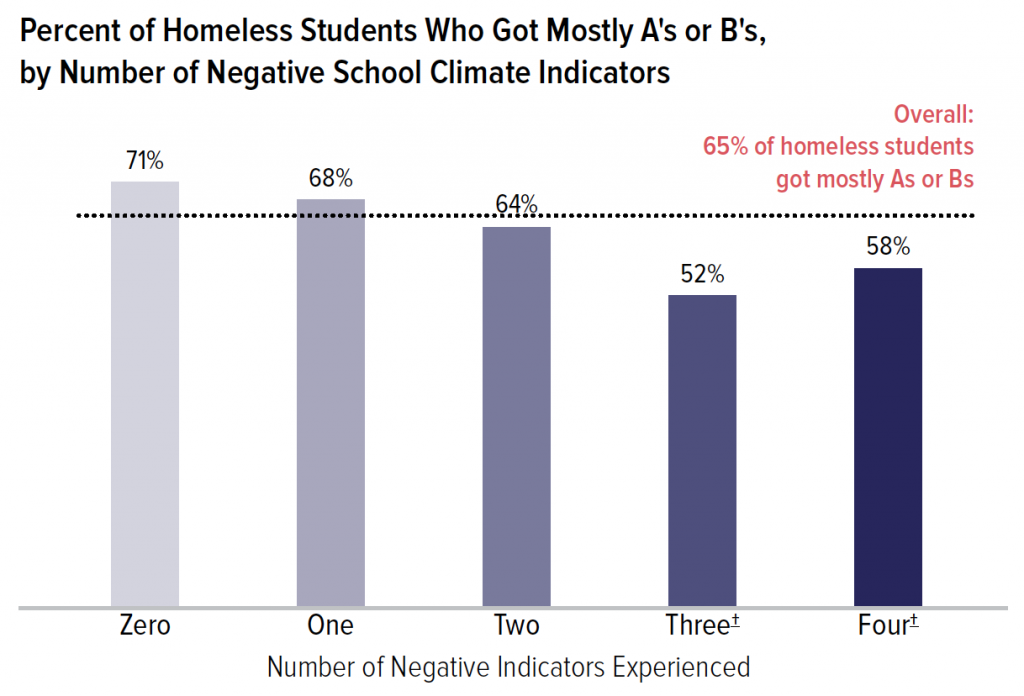

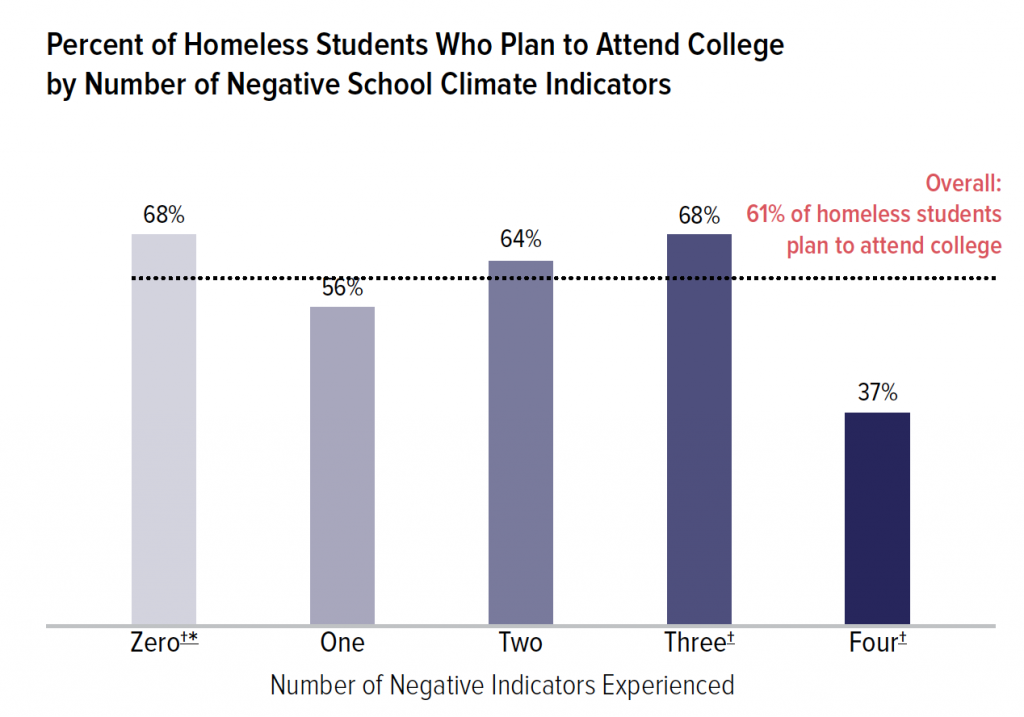

How Does School Climate Affect Homeless High Schoolers’ Academic Performance and College Plans?

Overall, 65% of homeless students got mostly A’s or B’s. Just 58% of homeless students who experienced all four negative school climate indicators got mostly A’s or B’s, 13 percentage points lower than homeless students who experienced zero negative school climate indicators (71%).

Across school climate groups zero to four, 61% of homeless students planned to attend college, yet only 37% of homeless students who experienced all four negative school climate indicators planned to attend college or pursue other post-secondary education. This was 1.8 times lower than the rate for those students who experienced zero negative school climate indicators (68%).

While most of the outcomes examined in this report show a clear trend between the number of negative school climate factors experienced and the outcome, this linear trend is less visible for homeless students’ college plans. This could suggest that there are many external factors that influence a student’s ability to attend college, such as parental educational attainment, lack of resources, and personal family dynamics.

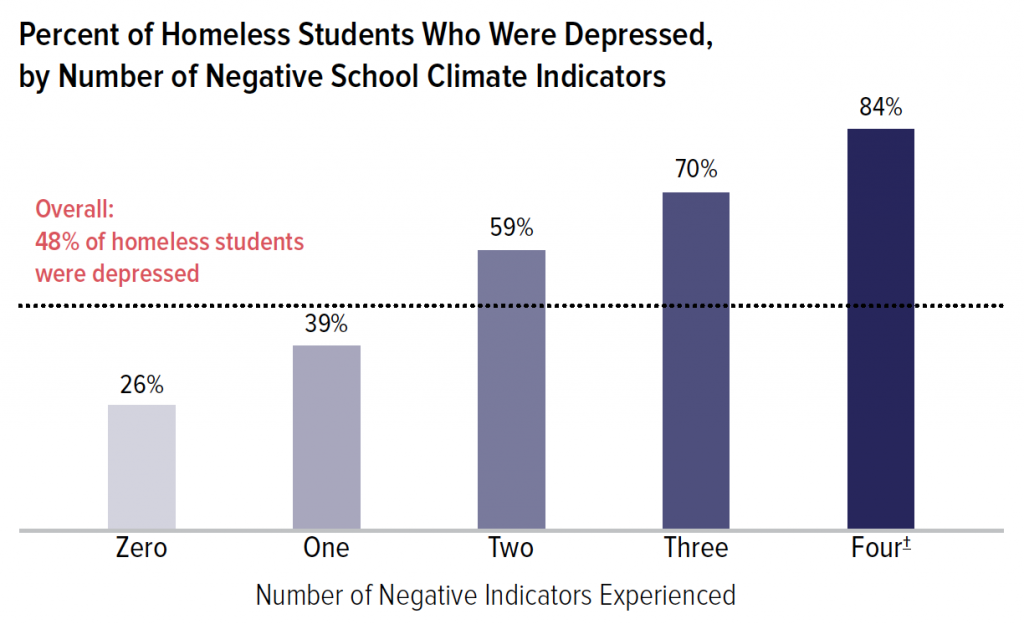

What Is the Relationship Between School Climate and Mental Health?

Although depression is not an uncommon experience for homeless students—overall 48% of homeless students reported suffering from depression—there was a clear correlation between the quality of school climate and rates of depression.

Homeless students who experienced all four negative school climate indicators (being bullied, missing school due to feeling unsafe, lacking positive relationships with adults at school, and being offered, sold, or given drugs at school) were nearly twice as likely to experience depression as homeless students overall (84% vs. 48%), and more than three times as likely to report being depressed than those who experienced zero negative school climate indicators (84% vs. 26%).

Of all the outcomes examined in this report, school climate

had the most dramatic impact on homeless students’ mental

health.

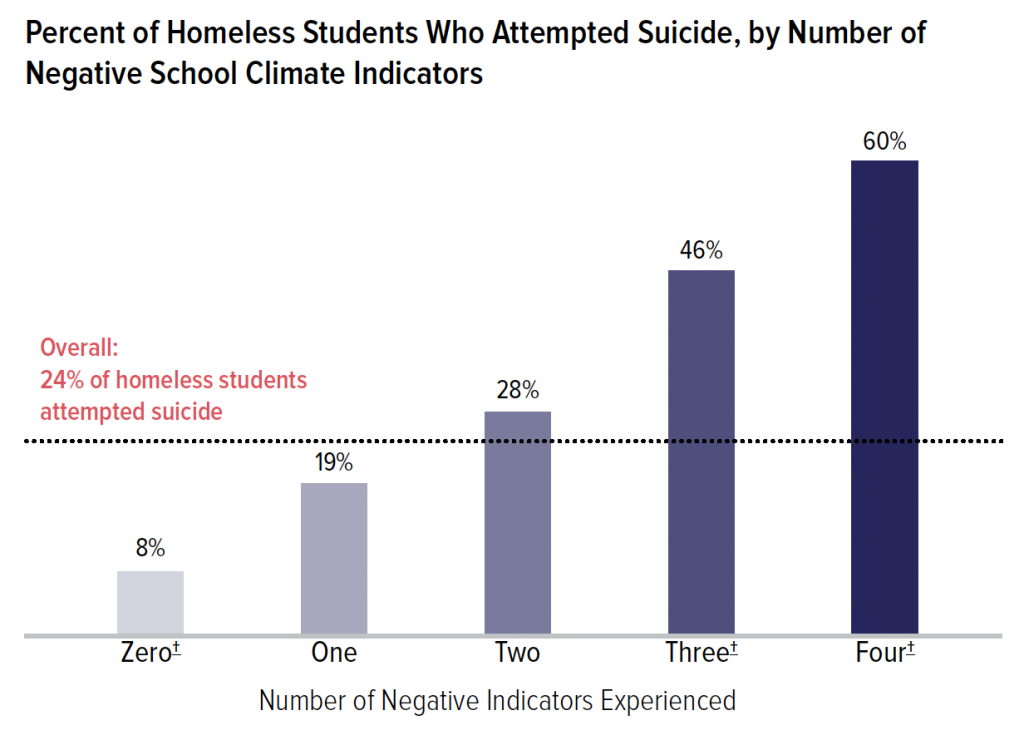

Rates of suicide attempts among students who experienced homelessness, categorized by the number of negative school climate indicators experienced, followed the same trend as depression. Three out of every five homeless students (60%) who experienced all four negative school climate indicators attempted suicide. These students were about 2.5 times more likely than homeless students overall (24%) and over seven times more likely than those who experienced zero negative school climate indicators (8%) to attempt suicide.

Housing instability, academic achievement, mental health, and school climate are intertwined in such a way that it is impossible to measure exactly which aspects of a student’s experience with homelessness and school climate are influencing their academics and mental health. However, it is clear that homeless students who perceive positive school climates experience superior academic and mental health outcomes than their peers who perceive negative school climates. The data show the vital role of schools as foundations of safety and stability for students experiencing homelessness, mitigating some of the negative impacts of housing instability.

Policy Considerations

While many initiatives aimed at tackling homelessness tend to focus on housing, schools can play a positive role in the lives of students experiencing homelessness and should not be overlooked as a key point of service provision. School climate can be improved through investment in anti-bullying and safety measures, including training students and staff to prevent, identify, and address bullying. Homeless students would especially benefit from trauma-informed approaches to teaching and relationship-building in their schools, where teachers approach behavioral problems through a lens of understanding and support. Lastly, investment in school-based mental and physical health supports is essential to promoting the well-being of homeless high school students.

Previous research has shown that positive school climates have the largest impact on low-income students. In fact, positive school climates have been shown to serve as a protective factor against the negative effects of homelessness, reducing gaps in academic and mental health outcomes between housed and homeless students.6 When homeless students are engaged in their communities, feel safe at school, and build trusting relationships with teachers and peers, their housing status no longer serves as a roadblock to future success.

1 National Center for Homeless Education, “Federal Data Summary School Years 2014–15 to 2016–17: Education for Homeless Children and Youth,” https://nche.ed.gov/.

2 National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments, “School Climate,” safesupportivelearning.ed.gov, accessed September 30, 2019.

3 National Center for Homeless Education, Ensuring Full Participation in Extracurricular Activities for Students Experiencing Homelessness, November 2017.

4 CNN Wire, “New Jersey Principal Installs Laundromat at School After Homeless Students Bullied,” ABC 15 Arizona, August 21, 2018.

5 Emily Herr, Samantha Bielz, Shahera Hyatt, Pushing Back Against School Pushout: Student Homelessness and Opportunities for Change, California Homeless Youth Project, September 2018.

6 H. Moore, R. Benbenishty, R. A. Astor, and E. Rice, “The Positive Role of School Climate on School Victimization, Depression, and Suicidal Ideation Among School-Attending Homeless Youth,” Journal of School Violence 17, no. 3 (2018): 298–310; M. O’Malley, A. Voight, T.L. Renshaw, and K. Eklund, “School Climate, Family Structure, and Academic Achievement: A Study of Moderation Effects,” School Psychology Quarterly 30, no. 1 (2015): 142–157.

Note: Unless otherwise stated, data are reliable and significant with p-values <0.05.

† Data have a relative standard error >=30%, a confidence interval half width >=10%, or an unweighted denominator <50.

Interpret data with caution.

*Data have a p-value >0.05. Interpret data with caution.

Appendix

Negative School Climate Indicators

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, President & CEO

Aurora Zepeda, Chief Operating Officer

Andrea Pizano, Chief of Policy Research

Chloe Stein, Principal Policy Analyst

Rachel Barth, Senior Policy Analyst

Katie Puello, Director of Communications

Hellen Gaudence, Senior Graphic Designer