Publisher’s NOTE

Dear Reader,

We at ICPH proudly present the Fall 2012 issue of UNCENSORED, which continues to examine family poverty and homelessness as well as the efforts being made to combat them.

With the latter in mind, we offer three features on programs aimed at helping those who find themselves homeless. One story focuses on a school in Baltimore, The Ark, which works to reverse the negative effects of unstable housing on language development in preschool-age children. Another feature concerns ways that the legal community can take advantage of federal legislation to help older children in the foster-care system who may be without homes between placements—or who “age out” of the system without the means to take care of themselves. Our piece on a New York domestic-violence shelter is written by one with firsthand experience there: a journalist who moved reluctantly with her year-old son to the facility, where she joined a community of women working to overcome their circumstances and safeguard their families.

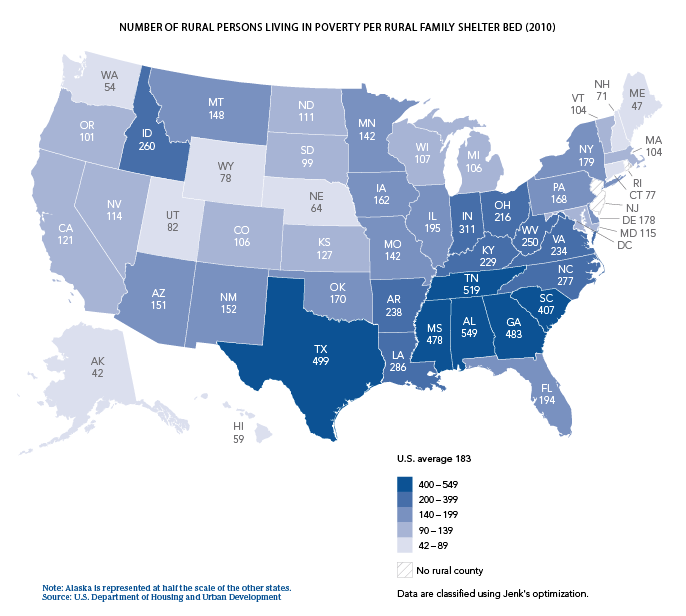

This issue’s National Perspective article takes a look at the topic of rural homelessness, while our Historical Perspective essay delves into the story of mothers’ pensions in the U.S.—who received them, what the criteria were, and how the debates surrounding them prefigured contemporary discussion.

In our efforts to shed light on these vital issues, we appreciate your comments, suggestions, and continued readership.

Sincerely,

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, Publisher

President and CEO, Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Finding the Words:

Programs Aimed at Fostering Language Development in Homeless Children

by Anita Bushell

Four-year-old Caty smiles as she spreads her beach blanket. She sits down, flips off her shoes, and looks at a book with her bear.

The dramatic-play corner of The Ark, a one-room preschool in Baltimore, looks like that of any other classroom for young children. There is a dress-up bin from which Caty extracts a pair of bright, purple slippers. “Do we wear slippers at the beach or do we wear sandals?” a teacher asks.

Developing appropriate language skills is a top priority at The Ark, because the students are being groomed to enter the Baltimore City public-school system. They are also homeless.

Children learn words and come to understand how their meanings change in different contexts.

“I believe that these skills are critical for all children and are of particular importance for the transient population that we serve at The Ark,” says the program’s director, Nancy E. Newman. She adds that language skills, which children develop largely in the crucial preschool years, “are not the focus of adult attention while their families are in crisis.”

Ms. Newman (as the children call her), a licensed social worker, leads a team that includes four teachers, a speech therapist, a part-time family-services coordinator, and prescreened “language volunteers,” because the children the program serves—up to 20 per day—need additional one-on-one support in basic communication skills. “We can increase vocabulary for educational outcomes,” Ms. Newman explains, and “for social relationships.”

Such an increase is a daily goal at The Ark, because teachers find that students entering the program often don’t know “universal” words, such as “spoon” or “plate.” They often don’t know the names of basic body parts, such as “head” or “neck.” “Who can tell me what this is?” Ms. Tonya, a teacher, asks the children during circle time while pointing to her elbow, then her wrist.

The development of language skills begins at birth, and research has shown that later reading delays can often be attributed to insufficient linguistic stimulation. Shelly Chabon of Portland State University, currently president of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA), says that in ASHA’s view, “programs designed to help homeless children with … language facilitation can serve an important and needed role in the community.”

“That’s where we step in,” says Ms. Newman, who asks Caty for help in sticking a new student’s name label in her cubby. “I tell parents, ‘Your kids learn to read the words they know.’” The children are thus coached throughout the morning in simple communications skills, being told, for example, “Use words.”

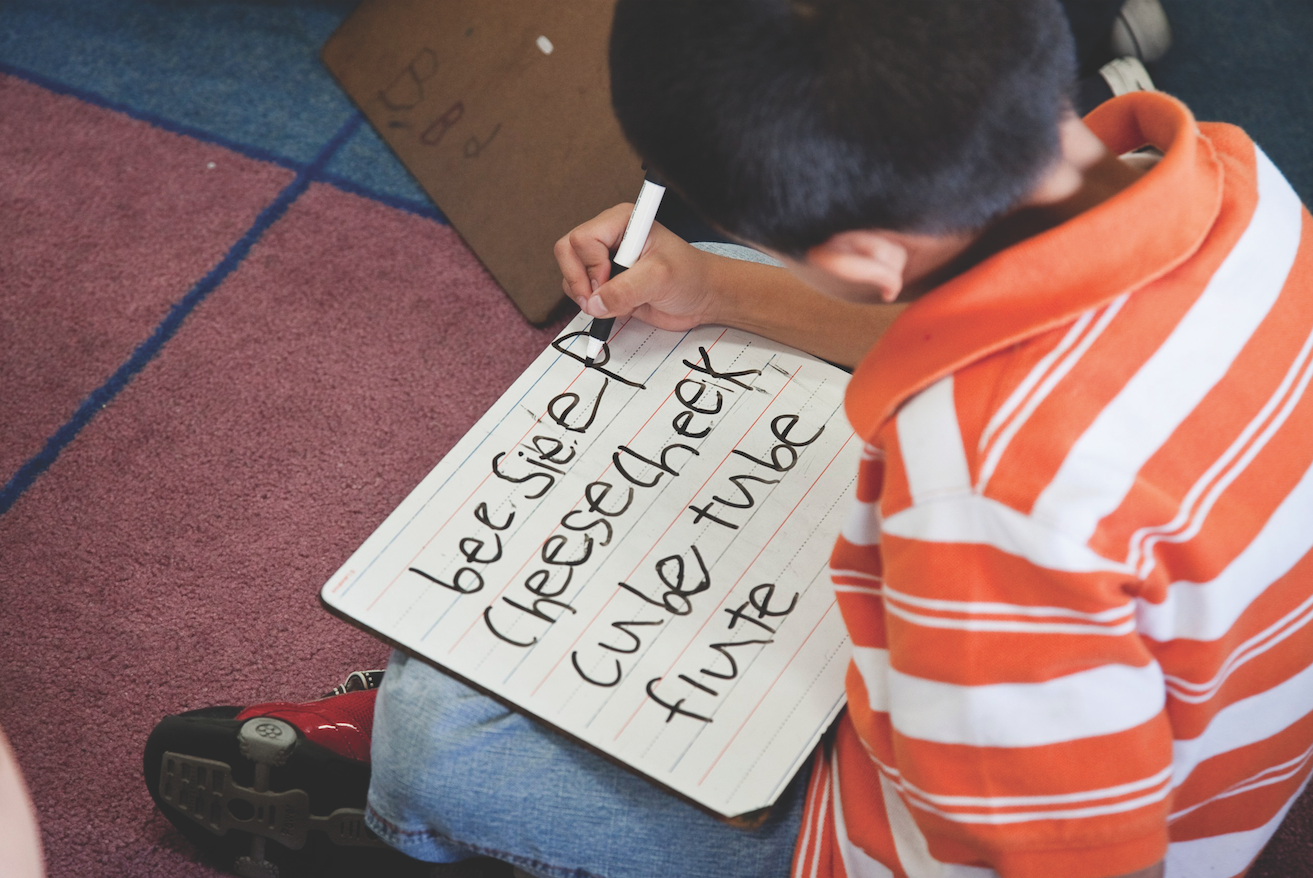

A young student enjoys the learning process.

Language development at The Ark, though, goes beyond everyday vocabulary building; it stresses contextually appropriate usage as well. Caty, who has been in the program since March, places a stethoscope on Mr. Bryan’s arm. Another girl uses the syringe on his cheek. “Did you get a shot in your face?” Mr. Bryan asks. “Give me a shot in my arm!”

Ms. Newman recounts how the children once ate bananas for snack; a few weeks later they didn’t remember what “bananas” were. Such episodes bear out researchers’ findings that in order to increase vocabulary, children need constant practice of and exposure to words—in addition to an understanding that words can appear in differing contexts. During circle time, Ms. Tonya reads The Great Wave and discusses the difference between an aquatic wave, a “hello” wave, and a wave at an Orioles game.

The Ark, a program of the Episcopal Community Services of Maryland, has served homeless children since 1990; it has evolved into a preschool for three- and four-year-olds focusing on school readiness. Partnering with Head Start, which funds one of The Ark’s teaching positions, the preschool works to ensure that children are “expressive, curious, and ready to learn” when they enter kindergarten. The Ark has been accredited through the Maryland State Department of Education since 2007. Other preschool programs for homeless children around the country include Morningsong Early Learning Center, in Seattle; Horizons for Homeless Children, in Boston; the Bessie Pregerson Child Development Center, in Los Angeles; the Compass Children’s Center, in San Francisco; House of Tiny Treasures, in Houston; and Miami-Dade CAA Head Start/Early Head Start.

“The Ark preschool is a place of stability, learning and healthy food for Baltimore’s most vulnerable and at-risk young children,” says Mark Furst, president and CEO of United Way of Central Maryland. “While their families are under enormous stress, looking for permanent housing and work, children at The Ark have normalcy in their lives that allows them to continue their learning and stay healthy. It helps ensure they will have the skills needed to succeed in elementary school and beyond in preparation for a self-sufficient life.”

Licensed to serve 20 students daily, The Ark takes in as many as 75 annually, with an average stay of anywhere from one day to 16 weeks. Ms. Newman, who has been with The Ark for 11 years, started out as the program’s social-services coordinator. She has been the director since 2003. The “revolving” nature of the program, she says, is a challenge. The preschool years are when youngsters start to build trust and form bonds with peers, which they cannot do if they stay in settings only temporarily.

Another challenge is coaching families in effective communication skills. Daily attendance, with exceptions for illness, is required, and any family that neither brings their child nor calls with an explanation three times in a 30-day period is given a warning that they are in danger of being removed from the program and placed back on the waiting list. “This is not a drop-in center,” Ms. Newman tells parents, “this is a school.”

That said, Ms. Newman will provide bus passes, alarm clocks, and a lot of time to help families correct whatever problems they are having, so that their children can benefit from the program daily. Having a consistent arrival time is crucial for children like Mike, who comes in today later than the other children, at 11:15. Mike’s family recently obtained housing a good distance away from The Ark; his mother asked if he could remain at the school for the summer before transitioning to a permanent Head Start program in the fall, and because of the travel time involved, he is allowed to arrive late. When Mike, a middle sibling, entered the program in September 2011, he was living with his mother and two brothers in a city shelter. The mental-health consultant who works with Head Start and The Ark found that he had speech and language delays and was emotionally unstable. As a result, he attends weekly play-therapy sessions and has had an Individualized Education Program (IEP)—a special-education program available through public schools—developed to address his speech and language needs.

A boy masters an essential skill.

Working with families is part of The Ark’s effort to create a community built on trust and on a concern for the whole of the students’ lives. Beyond educating children, Ms. Newman helps homeless families gain access to resources they need when they get back on their feet. The Ark relies on a range of community resources, such as donations of linens and cooking supplies, as well as help from a youth-group program that provides cleaning supplies for families moving into permanent housing.

While The Ark supports families, it also receives support of various kinds from local institutions. “Service learning” partnerships, which take place with Loyola University Maryland, allow the university students to teach and interact with children from The Ark as part of Loyola’s undergraduate curriculum. Even local seventh-grade girls from the private Garrison Forest School are recruited to support learning at The Ark, with adult supervision. The Garrison Forest relationship has resulted in a new collaboration: in September 2012, through Garrison Forest’s ties to the Irvine Nature Center, students at The Ark began making monthly visits to the center to get exposure to more science- and nature-based learning.

Suzanne, whose son, A.K., was in the program for a year and a half and is now in first grade, says that The Ark taught A.K. “about sharing.” She adds, “It is a very versatile program and was a big stepping stone for A.K. The Ark got the children ready for learning—moving up in the world.” There are, she says, “a lot of nationalities” represented at the school, which taught A.K. “about different people on a different level; he learned to say his numbers in Spanish.” The Ark, Suzanne notes, “was more to me than a typical preschool. They helped my child and they helped my family; they did something for Christmas and for Mother’s Day; they provided food and coats, free trips; there were computers set up for the parents. But it wasn’t only about the resources—they were 150% supportive of the family; so many things they did for the kids. They taught A.K. to accept people for who they were no matter where they came from … . A.K. didn’t want to leave—he was excited to go to school in the morning. I’ve recommended that program to many families.” Ms. Newman, Suzanne says, “is one of my mentors; I love her.”

A typical day at the The Ark begins with Mr. Bryan or Ms. Jasmine picking up children in a van from several local shelters. When they arrive their hands are slathered with Purell hand sanitizer, and they eat breakfast—cereal with milk—at two large tables. The meal serves as an opportunity to practice language skills. Ms. Tonya asks one of the boys, “Would you like some more?” He nods. “Can I have some words, please?” she responds, then elaborates, “May I have some more cereal, please?”

Ms. Newman notes that all entering children are screened with the Early Screening Inventory—Revised (ESI), used in many preschools, to determine if there is a need for more in-depth evaluations. In 2005, because of challenges Ms. Newman and her staff were facing, she raised a question at the first annual Young Children Without Homes Conference, in Boston, sponsored by Horizons for Homeless Children: “How are you assessing your children when they come and go so quickly?” Ms. Newman and her team of teachers have since developed an assessment system, the “Child Development Data Sheet,” used in conjunction with ESI, that expands and customizes linguistic evaluation for the specific needs of the transient children at The Ark. The children are assessed regularly; questions are based on developmentally appropriate language and range from the basic (can the child identify his or her ears?) to the more complex (can the child repeat an eight-syllable sentence: “There are five boys and three girls here”?). “I want to see vocabulary growth by the second assessment,” says Ms. Newman.

That approach supports linguistic learning for children like Caty, who is the middle sibling of three children living with their mother in shelter-supported housing. Their father lives elsewhere but is involved in their care. Caty struggled with separation in the beginning of her stay at The Ark, but after a period of adjustment, she began to participate in all activities and even started talking quietly to teachers on a one-to-one basis.

While Caty’s assessments displayed developmentally appropriate skills, children exhibiting language or speech delays are referred for further evaluation to The Ark’s on-site speech pathologist, who is grant-funded (initially by the United Way). This streamlines the process of delivering services if a child is deemed eligible for an IEP. If other delays are suspected, students are evaluated through Head Start. Ms. Newman continually tries to track children so they don’t get “lost” in the Baltimore City social-services system. “Our challenge is to monitor children in order to make a difference,” she says.

After breakfast, a cart is wheeled in with Dixie cups that contain dabs of bright pink toothpaste. “Tooth-brushing time” occurs daily, in addition to twice-monthly dental screenings and fluoride treatments conducted through the Baltimore City Health Department. (As a result of the Deamonte Driver case, the state of Maryland created Healthy Teeth, Healthy Kids, a program funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, to educate low-income and homeless families on the importance of regular dental care. Deamonte, age 12, died in 2007 from a brain infection, a result of a tooth abscess. His mother had neither the money nor the dental coverage to have the tooth pulled.) Bottled water arrives, as well, because tap water at Johnston Square Elementary School, where The Ark is located, is not potable—it’s laced with lead.

Ark children also receive regular hearing and vision screenings and are eligible for medical assistance through Medicaid. According to a report prepared by the Minneapolis-based nonprofit organization Family Housing Fund, “Homeless children consistently exhibit more health problems than housed poor children.” Ms. Newman regularly talks to parents about the importance of consulting a primary-care physician, rather than going to the emergency room, for medical care.

Eating healthy food is part of the day’s activities at The Ark.

After tooth-brushing time the children gather on the rug to look at books—some on their own, some in the laps of teachers and volunteers. The classroom fills with adult voices reading titles such as There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly while children answer questions posed to them, such as “Do you see the spider?” or “What color is the bird?” Repeated exposure to books throughout the morning supports literacy learning for The Ark’s children, who, as Ms. Newman states, are “doubly segregated by poverty and homelessness.” There are approximately 1,860 to 3,700 homeless young children in the Baltimore area who do not have access to high-quality early child care.

During circle time, Ms. Tonya reminds the children that they have learned a new word: “When earth and sky meet: horizon. Say ‘horizon.’” Before the children line up to go to the playground, she instructs them to tell a teacher or volunteer when they have found the horizon outside. She also holds up a poster showing a seascape: there are clams, crabs, and a sailboat. “See the horizon?” she asks.

Citizenship skills are promoted throughout the day. Ms. Tonya holds up a bottle of soap bubbles. “Do we fight over bubbles? No, we share.”

Outside, the early-July sun beats down on a blacktop surrounded by brick walls. There are no trees. Across the street are boarded-up row houses. As the children play, Ms. Newman describes a documentary called The Tradesmen: Making An Art of Work, which focuses on Baltimore painters, carpenters, and welders to illustrate the change from a labor force that worked with its hands to one that is service-based—a change that has resulted in the demise of the working middle class. The loss of jobs, in addition to housing foreclosures and other obstacles to making ends meet in the current economy, has contributed to the rise of the “new” homeless: not “bag ladies” or unkempt men but whole families unable to support themselves. Watching the students blow bubbles, Ms. Newman reflects on solutions to this enormous and growing crisis. “The potential is here,” she says. “This is where we should be putting our energy: into children.” Ms. Newman also wants to educate younger generations about the realities of the “new” homeless: “I want to work with college-age students; soon they are going to become voters and choose careers. I want them to understand they can put leaders in office who will care.”

Johnston Square Elementary, built in 1963, has served as The Ark’s home since October 2011, when the program itself became homeless. The Ark lost its former home, in a community facility owned by the Greater Baltimore Medical Center, when the building was put up for sale. At Johnston Square the halls are empty (there is no summer program), and it is very quiet, save for the lively sounds emanating from The Ark classroom; the program is administered from a cramped office. “This is not ideal,” Ms. Newman admits. “We had room to spread out in our old space.”

Back in the classroom, the children are instructed to sit on the rug once more. Ms. Tonya waits for the children to settle down. “Remember, we talk about being a good listener,” she says.

“Should we sing to the sun again”—the question refers to “Mr. Sun,” the song the children sang earlier in the morning—“or has he had enough?” Ms. Tonya asks. “He’s had enough!” the students answer loudly. The lyrics to “Mr. Sun” are printed on a large piece of poster board (which also has an illustration of a warm, yellow sun) so children can make the connection between the letters in front of them and the words they sing. Other “environmental print” includes a picture representing changing seasons (“We love spring!”), images and labels of fruit, and the lyrics to “Over in the Meadow.” Literacy is also supported at the writing table where Caty drew earlier with a fat, beginner pencil while wearing fake-fur gloves from the dress-up bin. Caty’s “shyness limits her interaction with others,” Ms. Newman states, “but with the consistent routine offered at The Ark, she is slowly becoming more comfortable and participating more.”

Mike lies on the rug and plays with two long blocks. Another child wants to play as well. “He’s having some time to transition,” Mr. Bryan tells the child, referring to Mike, who arrived late. Such individual attention helps children who may not be able to simply jump into the group dynamic.

At The Ark there is a poster pinned to a wall, My School Pledge:

Today in school I will

Listen to my teachers …

Be kind to others …

Do my very best.

In the circle, Ms. Tonya announces, “Tomorrow is the Fourth of July; our country is celebrating its freedom.” Tomorrow, she tells the children, there will be no school.

“My mommy’s going to be angry!” one child announces.

Resources

The Ark; Baltimore, MD ■ Portland State University; Portland, OR ■ American Speech-Language-Hearing Association; Rockville, MD ■ Episcopal Community Services of Maryland; Baltimore, MD ■ Maryland State Department of Education; Baltimore, MD ■ Horizons for Homeless Children; Roxbury, MA ■ Compass Children’s Center; San Francisco, CA ■ House of Tiny Treasures; Houston, TX ■ Miami-Dade Head Start/Early Head Start; Miami, FL ■ Loyola University Maryland; Baltimore, MD ■ Garrison Forest School; Owings Mills, MD ■ Irvine Nature Center; Owings Mills, MD ■ United Way of Central Maryland; Baltimore, MD ■ Baltimore City Health Department; Baltimore, MD ■ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA ■ Family Housing Fund; Minneapolis, MN.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The System and Its Children:

How the Legal Community Helps Older Children in the Foster-Care System Overcome Challenges of Education and Homelessness

by Joseph Sora

As many as 30% of the nation’s homeless adults “graduated” from foster care. In many cases those individuals entered foster care as older children, upwards of 12 years of age. Such children—many of whom have experienced a variety of trauma, from homelessness to physical and sexual abuse—pose a particular challenge to the nation’s foster-care system, which is often referred to simply as “the system.”

The system can have a tough time finding good homes for older children. Because of their ages and histories (which usually must be disclosed to prospective adoptive families), older children have little chance of being adopted. They can simply linger in the system, going from placement to placement, until they turn 18 and “age out.” They are often homeless between stays in the variety of placements—shelters, foster homes, group homes, and the residences of friends and relatives—that typically house them. During those times they might spend a few nights on a relative’s couch, then another few nights on another relative’s couch. Many do not see doctors, attend school regularly, eat well, or feel wanted by anyone.

A housing project in the area where the writer’s clients lived.

The plight of older children in foster care has, however, received attention from the social-services community in recent decades. In 1986 Congress first authorized funds to states to assist children leaving the system. The Chafee Foster Care Independence Program now governs that area of federal activity. Recently, some states have begun to provide services specifically for these children, independent of their implementation of federal monies. For example, social workers in Pennsylvania, North Dakota, California, and Illinois often follow an approach called “family finding,” through which children are reunited with a variety of family members. Family finding targets older children, who are substantially less likely to find permanent living situations otherwise.

In addition, the legal system has produced other legislation well-suited to addressing some of the particular issues that older children in the system commonly face. The federal McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act of 1987 provides children with educational stability, guaranteeing their right to attend their local schools or the schools they attended before entering the system, thus helping them overcome residency requirements for enrollment. Stability in any area of life, let alone education, is a critical need for these children. Some states have passed laws that allow children to re-enter the system after they have aged out; Illinois and Pennsylvania, for example, did so this year. Such laws recognize that those who enter as older children often leave completely unprepared for the world outside institutional walls.

“Eddie” and “Tasha,” residents of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, entered the system as older children. Both spent time in foster care; both also experienced homelessness before and after they aged out. I came to know Eddie and Tasha as their court-appointed attorney, or guardian ad litem. Since the foster-care system is managed by a state or county agency, that agency’s authority is determined in a court of law. Appointed as Eddie and Tasha’s guardian ad litem during their last year in the system, I had the job of advocating for their “best interests” before that court. To the extent possible I invoked both McKinney-Vento and state law permitting re-entry to force the system to accommodate my clients’ needs.

My clients’ names and some other details about their lives have been changed here to prevent their being identified. Their stories are not uncommon among older children in foster care.

The System

Operating at either the state or county level, the system includes local social-services agencies and their social workers and administrators. Entering the system works more or less this way: A report arrives at a local social-services agency. That report typically emanates from a school, the police, or a person familiar with a particular family, such as a neighbor or relative, and may concern the physical abuse of a child, deplorable living conditions, illicit drug use by the parents, or any number of other situations in which a minor’s safety is threatened while he is in a guardian’s care. The report is then investigated by the agency’s caseworkers. If a credible threat to a child’s safety is discovered, the child enters the system. Often, the system will first remove the child from the guardian’s care. Shortly afterward the child may wake up in a group or foster home. Until that child is adopted or finds some other permanent living arrangement, she is likely to remain in the system.

The child’s guardian ad litem typically tries to employ legal mechanisms, such as McKinney-Vento, to compel the system to address the child’s needs. McKinney-Vento permitted Eddie to remain in a particular school, regardless of whether he lived in that school’s district. The system also, again by virtue of a law, permitted Tasha to escape the streets by re-entering the system.

Eddie

Eddie has curly hair, blue eyes, and light-brown skin. As I often told him, he wears his pants too low. He could pass for 14; he was 17 and a half when we last spoke—a few hours before he left his independent-living facility, or group home, for good—and he still had no need to shave.

When I met Eddie he had just entered an independent-living facility with 13 other young men. Previously, he had stayed with his aunt in a nearby housing project. There simply was not enough room in the tiny two-bedroom apartment for Eddie’s aunt, her three young children, and Eddie, and the cramped conditions led to altercations. Eddie realized that the arrangement was not going to work out, so he ran away. The police picked him up, and I was appointed to represent him during what would be his last year in the system.

The abandoned factory Eddie passes on his trips to his old neighborhood.

Cars gave Eddie and me some common ground. During our first conversation Eddie was seated at a round table in a small interview room in the group home. To him, I was yet another system professional who would not know what to do with him. He was guarded at first, giving stock answers to my questions and seeming genuinely bored. He did pause, however, when I asked him (mostly out of frustration) what he wanted to do with his life. He then gave perhaps the only sincere answer to the many questions I’d asked: he wanted to be an auto mechanic. Since I am a car guy myself, Eddie and I spent the next 45 minutes talking about Porsches.

While living at his aunt’s, Eddie had been (sporadically) attending the local high school, whose well-known vocational program could teach him to be an auto mechanic. Eddie’s new group home, however, was not in that program’s school district. Prior to 2001, Eddie would not have been able to attend school in a district where he was not residing. Those who drafted McKinney-Vento, however, recognized that it takes an average of four to six months for students to catch up every time they change schools. McKinney-Vento also acknowledges that foster children, not surprisingly, switch schools far more often than other children—usually as a result of changing residences—and have, perhaps as a result, far lower graduation rates than children who are not in the system. McKinney-Vento obligated Eddie’s former school district not only to permit him to enroll but also to provide him with transportation to and from his old school.

I saw that decision as Eddie’s ticket to a life of gainful employment, with at least the basic necessities provided for. He would learn a trade in a setting that by now had grown somewhat familiar. McKinney-Vento would direct the system to provide what Eddie seemed to need most: stability and life skills.

Eddie started at the vo-tech program in his old school. He turned 17 that first week of school, and then he began to miss days. Within the first month after his 17th birthday, Eddie was skipping school three days a week and spending a good part of those skipped days walking the eight miles between the independent-living facility and the neighborhood in which he spent the first 12 years of his life.

Nine months ago Eddie stepped out of that facility and never went back. Six months ago a judge gave the county social-services agency permission to close Eddie’s case, thereby absolving the system of any responsibility for where Eddie lives or what happens to him. Eddie simply aged out without aging into anything else. He lacks stable housing, a high school diploma, and a marketable skill.

Eddie and Tasha wanted to return to the homes they knew before they entered the foster-care system.

Two years before Eddie left the neighborhood he referred to as “home,” his father was murdered in a drug deal gone awry. About one year later, and much to Eddie’s chagrin, his mother’s new boyfriend moved in. Verbal arguments between Eddie and his mother’s boyfriend turned physical, and six months later Eddie showed up at school with two black eyes. Just before he turned 13, his mother asked that Eddie be removed from the home.

Until he left home, Eddie had attended the same school. His relatives and friends lived close by. He had some stability in significant areas of his life. Following his removal, Eddie went to live with his grandmother, who could not provide the supervision an active 14-year-old boy often requires. Soon Eddie began staying at his brother’s apartment on weekends. He began smoking marijuana and took on a pattern of habitual truancy that prompted two stays at the local juvenile-detention center.

Eddie’s grandmother soon realized that she had little control over the boy, and so she gave what is known in the field as her “30 days”—that is, her notice to the social-services agency that Eddie could not live with her beyond another month. Eddie immediately ran away and was essentially homeless for the next three months, staying at an uncle’s, his brother’s, a friend’s, and his aunt’s. He went on to live in two or three group homes and, finally, in the independent-living facility where we met and where he last had contact with the system. When I think of Eddie, I always picture him walking to the neighborhood where he lived before his father was murdered.

Eddie can, however, return to the system. In the past, when a child aged out, placement in the system was no longer an option. However, in July 2012, Pennsylvania—like 15 states before it—passed a law to permit children who depend on the system to re-enter it after turning 18. Such laws were made possible by the federal Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008, which issues funding to states to provide care and other assistance for those over 18. Like McKinney-Vento, these laws provide the most benefit to those children who enter the system at an older age and, like Eddie, leave without permanent living situations or the skills to forge them.

Tasha

Tasha personifies the term “failed adoption.” Any mention of “failed adoption” to those who work for the system will usually trigger a slow, sad shake of the head. The failed adoption is an instance of the system failing, usually after much effort and expense, to secure for a child that elusive permanent living situation, after concluding that it had found just that. And since no child can be adopted unless the rights of the biological parents have first been legally terminated by the court, the failed adoption amounts to the state creating a legal orphan: a child who is without birth or adoptive parents.

I was appointed to represent Tasha shortly after her adoptive mother put in her 30-day notice and Tasha was taken to the first of what would be several group homes. When I met Tasha, at the first of those residences, she was visibly angry. She had recently been restrained for fighting with some of the other girls who lived there. Our first conversation was brief and focused on whether I could get her out of this particular group home.

As it happened, Tasha found her own way out: she ran away. That, in fact, was how she left just about every group home in which she was placed, until she was put in an out-of-county home several hours from where she grew up. Running from that facility would have led Tasha straight into the woods. As I visited her there, every six weeks or so, I became her only connection to the region in which she grew up, the area that she missed terribly. We had long conversations while walking around the campus where she lived. It soon became clear that Tasha, like Eddie, simply wanted to return to what she thought of as home.

Tasha is the youngest of her mother’s three children. Her mother had become addicted to crack cocaine shortly before her daughter turned seven. When Tasha was found in her mother’s home by the police, the small one-bedroom apartment was filled with garbage and cigarettes stubbed out in food so old it had drawn the countless flies that were Tasha’s only company at the time.

Tasha’s mother had fits of recovery while Tasha lived first in a shelter for children and then with the “aunt”—a close friend of the mother—who eventually adopted her. Those brief periods of being off drugs stalled the adoption process, because Tasha’s mother very much wanted her daughter to return home. Two and a half years after Tasha was removed, her mother lost her parental rights.

The aunt had escaped the projects that swallowed her friend, Tasha’s mother. She worked as an executive secretary for one of the very few major corporations still in the region. The aunt was afraid that Tasha would follow the same path as her mother. As Tasha entered adolescence that fear was borne out, when males much older than Tasha began to notice her natural beauty, almond-shaped eyes, and high cheekbones. And Tasha, who had always been far more comfortable around boys than with girls, began to take note of their interest.

When it became apparent that Tasha was becoming more than friends with men, not boys, Tasha’s aunt took steps: she implemented an early curfew and began to read the text messages on Tasha’s phone, before taking the phone away. As the rules become more restrictive, the conflict between Tasha and her aunt escalated. After one year of Tasha’s consistently breaking those rules, the aunt put in her 30-day notice. Tasha then ran away, living for four months with various friends and relatives until she was picked up by the police and placed in the first of several group homes in which she would reside.

The bridge Eddie crosses to visit the neighborhood where he spent his earliest and happiest years.

Leaving the system when she turned 18, Tasha went back to the very projects where she had spent her first seven years and where her mother still lived. The next eight months were difficult. She slept at friends’ apartments, on the streets, and in shelters. A counselor, with whom she kept in touch after aging out of the system, located her in a shelter for homeless women some 200 miles from her birthplace. He told her about a recently passed law enabling those over 18 to re-enter the system if they met certain criteria. No one wants to go back into the system, but Tasha, much to her credit, realized that she did not have a lot of other choices at the time.

Tasha’s counselor contacted me, and we got her back in the system. As the judge stated at the hearing, the local law that permitted her to re-enter was aimed directly at those like Tasha: those who entered the system as older children and left without having learned to fend for themselves. This law gives Tasha—and the system—a second chance.

The bridge that Eddie crosses to get to his old neighborhood defines “dilapidated.” Long-abandoned factories sit on the river bank that leads to the streets where Eddie was born. Passing the empty factories and then several blocks of squat, three-level brick tenements, Eddie would thread several miles along a busy city street until he reached the familiar faces and corners of his old neighborhood. If he had kept walking another mile or so, he would have run into the housing projects where Tasha was born. Tasha’s mother is still there and, by all reports, remains severely addicted to crack cocaine. Tasha, however, has a room in an independent-living facility a dozen miles away. She has jobs at a gas station and a fast-food restaurant. Sometimes she works more than 75 hours in a week. She’s very close to completing her GED and hopes to move into her own apartment within one year, goals she seems well on her way to accomplishing, at least at the moment.

Older children are not likely to have an easy time in the system. There are reasons why they are there, and, typically, these reasons have lasting consequences. Advocates for these children—caseworkers, attorneys, counselors, and others—can insure that older children like Eddie and Tasha receive the maximum benefit from a system that is just starting to recognize how difficult their lives have been.

Resources

Allegheny County Department of Human Services; Pittsburgh, PA ■ John H. Chafee Foster Care Independence Program; Washington, DC.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The Unlikely Homeless:

One Woman’s Experience in a Domestic-Violence Shelter

by Pearl Brownstein

I am one of the unlikely homeless. I have a master’s degree and a career in publishing, and I was a co-op owner in New York City’s Chelsea neighborhood—yet my 10-month-old son and I now reside in a domestic-violence shelter in an area filled with crumbling tenements and public-housing towers. Oddly enough, our two months here have been a godsend for both of us.

Last summer, after I sold the co-op I’d owned for 15 years, I moved with my partner to a two-bedroom apartment in Park Slope, Brooklyn. At his urging, I quit my job to care for our infant son. On the surface, everything looked perfect, but problems between us had been brewing since I became pregnant. Then, suddenly, they escalated to such an extent that the life I’d known was shattered beyond recognition.

Two months ago, I hired a lawyer to file protection orders against my partner and his parents. I still had the jitters from what occurred during our vacation in California a few days before. We had been at a large gathering of friends and family, and when it ended I chose not to say goodbye to my partner’s parents, as they had been verbally abusive to me in the past. To avoid further conflict with them, I had put the baby in the backseat of our rent-a-car and sat in the passenger seat while waiting for my partner to drive off. Suddenly my partner’s mother approached the car and began banging on my window with such force that I expected the glass to shatter; then my partner’s father stuck his hand inside the door as if to grab me. I screamed in terror, and my son began to cry, while my partner stayed in the driver’s seat and did nothing to protect us.

A worker at a crisis hotline, where those in need of protection are directed to safety.

The following day was Mother’s Day, and my partner said that he would be spending it with his mother instead of the baby and me. In that case, I told him, he should pack his bags and leave the hotel. After that, he and his family called me repeatedly on my cell and hotel phones, but I did not pick up, as I was too frazzled from what was occurring to handle any more fighting. When I called the front desk, the staff there said that whoever was calling me sounded so angry that they were concerned for my safety. I asked them to tell whoever called next that I had checked out.

When my partner heard that I’d “checked out,” he contacted the local sheriff’s office and accused me of kidnapping our son. From the window of my room, I watched my partner park the rent-a-car in the hotel lot and enter with his parents, followed a few minutes later by the police, who knocked on my door. Trying to remain calm as I held the baby in my arms, I told the police that I had no intentions of kidnapping our child, that I simply wanted to go home and was concerned that I wouldn’t be able to leave without being assaulted. Mercifully, the police escorted me out of the hotel and permitted me to get on the next flight back to New York.

I booked an early flight for the following day. At the airport I happened to run into a friend. When I told her what had happened, she responded, “Do you really feel safe going home after that?” Over the coming months, the word “safe” would be echoed by legal counsel, shelter staff, and concerned friends and family. When we landed at LaGuardia airport, I called a college friend, who immediately offered my son and me her daybed.

A few days later, my lawyer relayed the details of what had happened in California to a family-court judge, also explaining other longstanding issues between my partner and me. My partner, who makes a six-figure salary, did not permit me to use our “shared” debit card or provide me with money, which left me no choice but to dip into my savings on a daily basis. The judge granted me three protection orders; my partner’s parents live a few subway stops away, and the judge was concerned that they might attack me in our home and that my partner would not protect me. Then the judge asked where my son and I were living. I said that we were staying with a friend, but that I planned to rent an apartment in Rockland County, just outside New York City. At this the judge promptly ordered me to remain within the city’s five boroughs—and to stay at a shelter.

I was near tears as I left the courtroom and furious at myself for revealing to the judge my housing plans. My image of a shelter was probably many people’s: a huge room filled with drug addicts, the mentally ill, and the destitute. It was certainly not a place for me—or for my son. People might have contagious diseases. While I was asleep, someone might steal my jewelry or my shoes. I said to my attorney, “Why do I need to stay at a shelter when I can rent an apartment instead?”

Shelter staff walk the residential floors hourly, monitoring for potential concerns such as stove top smoke, keys left in residents’ doors, and children crying uncontrollably.

She explained that the judge had ordered me to stay at a domestic-violence shelter to receive services and support, since more than 50 percent of women return to their abusers. I was incredulous, since I did not consider my strained relations with my partner and his family to constitute domestic violence, as that term, to me, suggests black eyes, bruises, and other signs of horrible abuse. But when I called the hotline number I’d been given for Safe Horizon—a New York City–based victim-assistance organization—and described my experience with my partner and his parents to the person on the other end, he said that I’d receive a callback in the next few hours with my shelter-placement location.

Brooklyn, where I’d been living, was deemed off-limits as an “unsafe borough” for me, as was Queens, where my partner worked. All I knew was that I would soon be residing in Manhattan, Staten Island, or the Bronx. While I waited for the call, my friend and I packed my bags. An hour later the phone rang, and the person on the other end asked, “Are you safe to talk?” She then provided me with the address of a McDonald’s in an unfamiliar neighborhood, where I was to wait for staff to escort my son and me to the shelter. To get there I took a cab, a last remnant of the more affluent life I’d been leading.

I soon discovered that where I had been placed was nothing like the nightmare I’d envisioned: it was a modern, five-story brick building. Here, every resident is provided with her own apartment, and depending on how many children she has, the sizes range from studios to three-bedrooms. My apartment would be 4D, a studio that contains a crib, a twin bed, a table and chairs, and an armchair and side table. There is also a kitchen area, a bathroom, a closet, and built-in shelves. The studio is one-quarter the size of my Park Slope apartment, but it is clean, new—the shelter is just six years old—and outfitted with everything my son and I need. When I first walked through the door, plastic bowls, plates, and cups, as well as cutlery and cookware, were arranged on the kitchen table. “To get you started,” one of the staff said quietly. The following day, a dolly arrived filled with various foods as well as shampoo, diapers, a baby bottle, and toothpaste.

This shelter, as I was told by the social worker who handled my intake process, is a short-term (emergency) 90-day facility for women with children. However, if one takes part in the shelter’s daily activities, among them community meetings; the domestic-violence support group; housing, entitlement, and financial workshops; the anger and parenting group; and individual meetings with one’s social worker, one’s family can remain in the shelter for up to 135 days. Presumably this would be sufficient time to put some distance between my partner and his parents, and I would be less likely to return to an increasingly unmanageable situation.

Domestic violence is the chief cause of injury to females ages 15 to 44.

All of the staff repeatedly reminded me to not tell anyone where I was living; if I met up with friends, they said, I must do so at least 20 blocks away. Even though I did not consider my situation to be extreme enough to warrant such strict measures, I have abided by them, for fear that otherwise I will be asked to leave. For safety purposes, even shelter staff must keep their workplace address confidential. “If a bouquet of flowers arrives here on someone’s birthday or anniversary, they’ll be fired on the spot,” one of the staff told me.

There are numerous other rules, too, many of which I initially found rigid, though I have now grown used to them. Only one resident at a time may use the laundry room. The shelter curfew is 10 p.m. on weekdays and 12 a.m. on weekends. When a resident signs in for the night, she cannot leave the building again under any circumstances. (I felt the sting of this rule one Sunday evening after signing in and realizing that my son had lost all of his pacifiers, which would have made for a sleepless night for both of us. Thankfully, my next-door neighbor gave me one, first pulling the pacifier from her daughter’s mouth and wiping it on her sleeve.)

My first few weeks at the shelter were a blur of appointments with various staff, including the associate director, the child-care director, the housing director, the nurse, the psychiatrist, and my social worker. I also met with the entitlement specialist, who assists residents with attaining public assistance (P.A.). She explained that the eligibility cutoff for food stamps and Medicaid is $2,000 or less in one’s bank account, and that because my savings exceed that number, I have no choice but to purchase food and any other necessities for my son and me out of pocket. Most women here qualify for P.A., as they have little or no savings and do not have jobs. (According to sources including the Allstate Foundation, lack of financial security is one of the primary reasons women end up trapped in abusive relationships and often do not leave home until the violence becomes unbearable.)

Other differences between me and the other shelter residents are immediately apparent. I am the only white woman—many still mistake me for shelter staff—and, in my early 40s, I am older than most of them. Many have not graduated from high school and have no job skills. Some residents do not speak English at all. Some are undocumented immigrants from Mexico, and a handful come from Africa. And yet, when we join together for the various classes held throughout the day, these differences feel inconsequential as the similarities among us come to light.

There is no place like home—the writer’s is 4D—even if it is only temporary.

Like many of the women here, I do not have a strong familial support system (my parents died years ago and I have no siblings). A majority of the residents arrive at the shelter with infants or toddlers in tow, just as I did; my social worker explained that relationships often turn abusive when women become pregnant.

In our anger and parenting class, which meets twice weekly, we are urged to release our negative feelings in a healthy way. Jan, the social worker who leads the class, encourages us to hit a chair with a towel or beat a pillow. Almost all of us resist, though a few residents freely admit to having punched their abusers in the face. We’re told that if we let our feelings out before they build up, we’re less likely to get into altercations that might lead to assault charges and a night behind bars. One of the women, Lorna, who has previously been silent in class, walks to the front of the room, takes the towel from Jan, and begins beating one of the chairs. “Say what you’re feeling,” Jan encourages, and for the first time I hear Lorna’s voice rise. “I hate you! I hate you! I hate you! I hate you! I hate you!” As she continues whipping the chair, she shifts her fury onto herself. “I’m so stupid! I’m so stupid! I’m so stupid! I’m so stupid!” Eventually, tired, she returns to her seat. “Do you feel better?” Jan asks. Lorna, still catching her breath, nods her head, and I can see plainly that where her facial expression had been strained, there is now relief.

During a meeting of the domestic-violence support group, which is led by Felicia, my social worker, a resident admits that she is considering returning to her abuser. She is overwhelmed by having to care for her six-year-old, one-year-old, and newborn on her own. All of the women—we sit in a circle—try to persuade her to stay in the shelter. Felicia says that it takes a woman, on average, seven attempts to leave her abuser. This stark statistic silences us—before she adds, “But then there are women like you who are brave enough to leave on the first try.” The social worker leading the group the following week says, “If you think your abuser was controlling before, he’ll be 100 percent more controlling if you go back to him.” I keep that thought in the back of my mind at all times. During these and other meetings, residents must leave their children in the child-care center down the hall, which, to ensure the safety of the children, is always locked with a deadbolt.

All residents and staff are required to attend the weekly community meetings (which are simultaneously translated into Spanish), during which various topics are discussed, such as “setting proper boundaries.” A couple of months ago, the Manhattan Educational Opportunity Center presented to the group on its various educational services, which include free GED and ESL (English as a Second Language) classes as well as vocational and college-planning programs.

Besides these required meetings, there is a host of other activities offered throughout the day to both mothers and children. Every Monday a schedule of the week’s events is provided at the reception desk. The occupational-therapy department runs daily classes ranging from “Mommy and Me” to cooking and money management. For the children, there are local swimming lessons and outings to the movies, the Bronx Zoo, and Central Park, while some of the older children attend a two-week sleep-away camp.

At one of the recent community meetings, we are told about the surgeon general’s statement that domestic violence is the most common health problem among American women. It is currently the chief cause of injury to females aged 15 to 44. The shelter’s associate director tells me that the rise in violence is directly related to the shrinking economy. “When unemployed men feel helpless, they can make themselves feel more powerful, at least momentarily, by taking it out on their families,” she explains. Besides the weak economy, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan also account for the rise in violence, as an increasing number of women entering the shelter, according to the associate director, are partnered with men who returned from overseas and suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder.

A child observes city life from his residence at a women’s shelter.

This shelter, which has 44 apartments and sleeps 96, is now filled to capacity. Even more disconcerting is that once a family’s 135-day stay is over, the choices for what’s next are increasingly limited. New York City’s budget has been so severely cut that there are no new housing subsidies this year. Most families who do not return to their abusers or leave the state with the approval of a family-court judge are brought to PATH (Prevention Assistance and Temporary Housing), a homeless shelter placement facility in the Bronx. Often, PATH will send a family to a transitional shelter until permanent public housing becomes available. Currently there are more than 160,000 families on the waiting list.

Unlike a majority of the women here, I will be renting an apartment at market value. The housing director encourages me to start small—“rent a studio,” she says. To save money, I had hoped to rent a two-bedroom with another resident and her son, but her former boss just offered her a job—the only hitch being that she has to move to California. Although I have a few months left to remain in the shelter, I still find myself staying up late to surf the Internet for cheap rents—which are few and far between in the safer neighborhoods—while my son sleeps in his crib just a few feet away. This is not an ideal time to get an apartment. According to my social worker, only 1% of the city’s rental housing is now vacant, which accounts for the sharp spike in prices. I can no longer afford Park Slope, where most of my friends live, as a studio now goes for $1,700 per month.

And even though my books, photographs, couch, coffee table, winter clothes, and most of my other belongings are now in storage, there is a part of me that does not want to leave this shelter and settle into an apartment of my own. Here, I am never alone. Despite our differences, there are women with children, living upstairs, downstairs, and across the hall, who are just like me. Most of the women here will have far fewer opportunities than I will when they leave, and yet their bravery strengthens me. The staff, all of whom knew my and my son’s names from the very first day, encourage me. We are a temporary community. Being here offers us the necessary distance from our abusers in order to begin healing. And with each passing day, we are further away from what brought us here—be it economic, verbal, emotional, or physical abuse—and one day closer to our new lives.

Resources

Manhattan Educational Opportunity Center; New York, NY ■ Allstate Foundation; Northbrook, IL.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Hope Behind Bars

by Stephen Brown

Of the number of women in prisons today, a figure placed at 115,779 in 2008, a high percentage are mothers. In mid-2007 approximately 65,600 women in federal and state custody reported being the mothers of 147,400 minor children. According to the Women’s Prison Association, 77% of incarcerated mothers said that they provided most of the daily care for their children before incarceration.

One of the most effective tools in combating prison recidivism, and giving female prisoners the best chance to care for their families upon their release, is allowing them to pursue General Educational Development (GED) degrees—the equivalents of high-school diplomas—and even college degrees while incarcerated. A September 2010 report by the New York State Department of Corrections finds that while male offenders have a 37% recidivism rate and females have a recidivism rate of 24%, earning degrees while in prison has a more pronounced effect on women, with males who earn degrees showing a 32% recidivism rate, compared with a 15% rate for females. Also of note is that those men and women who earn degrees while in prison are less likely to return than people who obtain degrees before being imprisoned.

Sister Tesa Fitzgerald (right), executive director of Hour Children, with a participant at Hour Working Women Program.

Incarcerated Women

With help from two nonprofit organizations dedicated to assisting women during the reentry process—the New York–based Hour Children’s Hour Working Women Program and A New Way of Life Reentry Project, whose offices are in South Central Los Angeles—UNCENSORED was able to interview five women who obtained their GEDs while incarcerated. (To honor their requests for anonymity, we have changed their names for this article.) Many different risk factors, including drug use and homelessness, placed them on the path to prison. “I was homeless, moving from hotel to hotel because of my drug use and not having a job,” one of the women, Robin, told UNCENSORED. Another, Linda, said, “My mom passed away, and I’ve been floating in and out of homelessness since I was 15, and now I am 51 years old. Drug usage and being irresponsible through my adult years left me homeless.”

For a woman, no matter what road leads her to prison, the consequences of even a short sentence and criminal record can be far greater than for a male offender. Often, when a father goes to prison the mother is still at home to care for the family, but the reverse is rarely the case. For female offenders, a prison sentence leads to separation from children, probation, and mandatory counseling sessions — which interfere with their search for work— as well as to the stigma of a criminal record, an additional obstacle to employment.

But obtaining a GED has a positive impact on these women’s chances to obtain employment and increase their earning power upon release. A 2009 report from the Urban Institute Justice Policy Center, Women on the Outside: Understanding the Experiences of Female Prisoners Returning to Houston, Texas, identified a GED/high-school diploma as a key predictor of whether a female offender will be employed eight to ten months after reentry. GED programs are not a panacea guaranteeing an easy transition from prison to post-release self-sufficiency, as the situations of three of our participants illustrate. “I haven’t been able to obtain employment, but gaining my GED was something less I had to accomplish and focus on,” said 25-year-old Wilmarie, who added, “It is important to at least have a GED in order to obtain a minimum-wage job.” Robin and Linda have had similar post-release struggles, responding negatively when asked if they have been able to obtain employment and if their GEDs have been helpful in their job searches. But two other women UNCENSORED spoke with, Stephanie and Barbara, shared better news, with Stephanie saying, “I achieved my GED in 1991 and was paroled in 1996. Since then my GED has helped me achieve many of my goals.”

“I achieved my GED in 1991 and was paroled in 1996. Since then my GED has helped me achieve many of my goals.”

The 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act prohibited federal and state prison inmates from receiving Pell Grants during their incarceration. Pell Grants assist low-income individuals in gaining access to post-secondary education; the 1994 act in effect killed hundreds of programs providing education to prison inmates. Today, half of women in prison participate in educational or vocational programming, but only one in five women takes high-school or GED classes, and only half of women’s correctional facilities offer post-secondary education.

The women we questioned all had different reasons for earning their GEDs while incarcerated, but they all mentioned hope for a better future as a factor. Wilmarie, who was convicted of attempted murder and sentenced to 3 1/3 to 10 years, said, “My motivation was to change the way I had lived in the past and to make a difference in my life. Achieving my GED gave me more hope, and I was able to believe in myself.” Two others mentioned their desire to help their children as an impetus. “With my GED I can now read to my children, which is something I love to do,” said Robin. Similarly, Barbara told us, “I was incarcerated doing a long term… at the time I had a small son. My focus and goal is that I needed to do this in order to provide care for him.” Another motivator mentioned by the women was the positive reinforcement from family and fellow inmates they gained from studying for the GED. Stephanie told UNCENSORED, “I wanted to do something positive in my life and learn all that there was available to me during my incarceration.” Robin commented that pursuing a GED “kept me focused and determined to get further in my education.” She added, “Having my GED, not only does it give me higher chances of finding a job, but I feel better about myself as a confident adult.”

Prison education programs need not end with GED obtainment. For example, the Ossining, New York–based organization Hudson Link for Higher Education in Prison partners with nearby Nyack and Mercy Colleges to offer free degree programs for both male and female offenders. According to Hudson Link’s Web site, it costs an average of $54,000 per year to keep one person incarcerated. Forty-six Hudson Link graduates have been released since 1998; none have returned to prison. For every year the 46 released graduates stay out of prison, New York State saves $2.48 million.

When asked if they plan on pursuing any additional academic or technical training, all five of our respondents said they have continued or plan to continue their educational journeys. Wilmarie said, “I am currently attending community college majoring in computer technology,” while Robin told us, “I want to go back to school and get a bachelor’s degree in social work and help families and children.” Linda’s plan is “attending drug-counseling school such as the California Association of Addiction Recovery Institute program,” and Stephanie said, “I am thinking about going to school to become a certified dental assistant.”

Robin happily reported, “Now I am able to read to my children and help them learn. If I hadn’t received my GED, I wouldn’t be able to do that.” Stephanie said to UNCENSORED, “My daughter is very proud of me.”

Studies show that prison GED programs reduce recidivism, increase long-term wage-earning power, and can be cost effective while lessening the well-documented overpopulation of American correctional facilities. Women who earn their GEDs while incarcerated learn that a prison sentence does not mean the end of hope for a better life for them and their children. “The GED programs are helpful, especially for the youth that may not have goals or a positive path,” Wilmarie said. Robin happily reported, “Now I am able to read to my children and help them learn. If I hadn’t received my GED, I wouldn’t be able to do that.” Stephanie said to UNCENSORED, “My daughter is very proud of me.” The participants we interviewed recognize the powerful role GED programs can play in prisoners’ lives. “I think every place that is as dark as prison truly is should offer education for everyone doing time. There is nothing better than being able to compete and to become a productive, educated member of society,” explained Barbara. Robin asked, “If you don’t give people [in prison] a chance to learn, how will they ever be successful adults in society?”

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

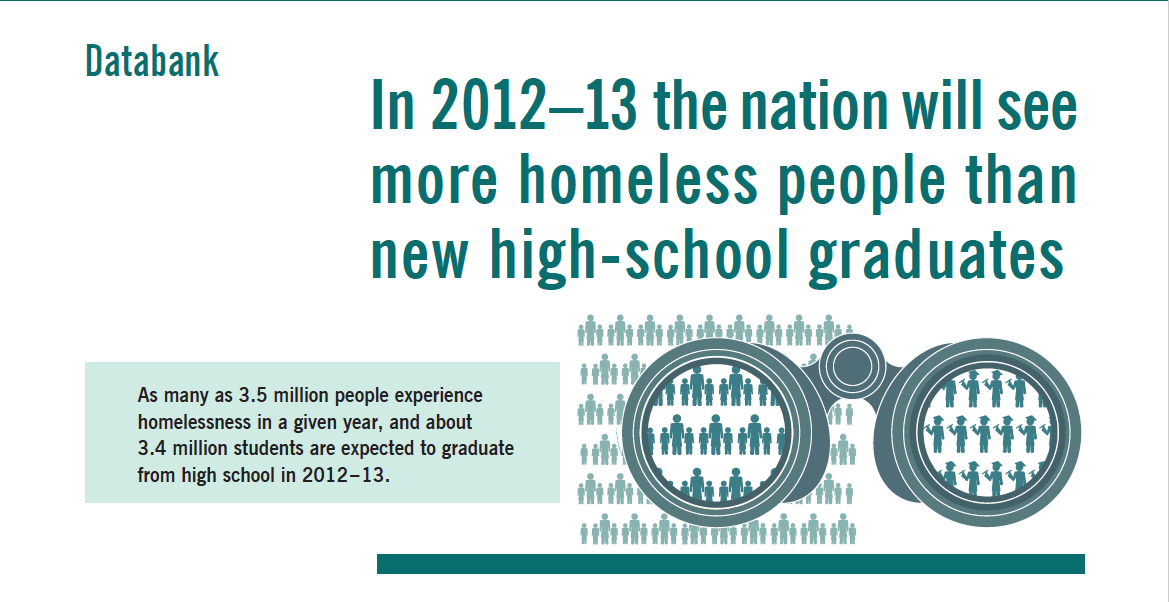

Databank

Resources

National Center for Education Statistics; Washington, DC ■ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD.

Click here to download this Databank.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Fighting for Homeless Children

by David J. Hickton

David J. Hickton was nominated for United States attorney for the Western District of Pennsylvania by President Barack Obama on May 20, 2010 and sworn in as the district’s 57th U.S. attorney on August 12, 2010. The author is grateful to U.S. Attorney’s Office intern Micah Gibson for his help with this article.

Upon taking office as United States attorney, in August 2010, I was resolved to have an active civil rights effort as a top priority in my work. Despite all the progress that has been made through the hard and dedicated work of many, the promises of our freedoms do not extend to all Americans. In practice, unfortunately, our pledge of liberty and justice for all means liberty and justice for some—not all—Americans.

In announcing a dedicated Civil Rights Section in the reorganization of our office, we took an important step in sending the community a message about our resolve. In addition, I came to know the civil rights activists and stakeholders much better. I learned that by simply breaking down the walls between individuals and groups dedicated to equal justice for all, we could unleash a reservoir of positive energy, multiplying the efforts of all involved. Investing in each community group illuminates the heroic work that was previously less visible.

Such work includes the great accomplishments of the Pittsburgh-based Homeless Children’s Education Fund (HCEF). That organization’s efforts have been driven by many distinguished community leaders and led by the seemingly boundless determination and brilliant vision of Joe Lagana.

Joe Lagana served for many years as a teacher and coach in public schools. Formed in 1999 at Joe’s “retirement” party, the HCEF provides hope through learning—seeking opportunities to educate and increase awareness of homeless children.

A priority of the HCEF is to champion the right to education for all children, even—especially—those made invisible by homelessness. Their plight, which is no fault of their own, is now the life’s cause of so many.

Western Pennsylvania has been identified as a leader in this national cause, and its efforts have aided children and helped fuel the civil rights work being done here.

A key event in this work was the 2009 case involving a local school district. A.E., B.E., M.E., minors, et al v. Carlynton School District, et al., filed in the United States District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania, was a suit on behalf of a suburban Pittsburgh family with two boys and two girls, ages six to twelve, who were to be excluded from school because they were homeless.

After they were evicted from their home, this family reached out to the Interfaith Hospitality Network (IHN) in Crafton, which provided them with a place to store their belongings. The IHN shelter could not provide them with overnight accommodations, however, so it placed them at a series of eight local churches. Although the IHN shelter was located squarely within Carlynton School District, a few of the churches where the family slept were outside it. Because of this technicality, the school un-enrolled the children.

The family petitioned Carlynton to re-enroll their children, but when the school year began, the Pennsylvania State Department of Education informed the school district that they were not obligated to do so, since the family “did not live in the District.” These four children, still struggling with being homeless, were left without any apparent educational options. Because they were without a permanent home, no school would take them.

Fortunately, this family had help. IHN put them in touch with the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty and the Education Law Center. The two organizations filed suit against Carlynton School District, demanding that it stop discriminating against homeless students. Within six months, the school district settled the lawsuit and agreed to enroll the children.

This story is not unique. As families have struggled in the current economic environment, it has become increasingly common. Approximately 1.35 million children face homelessness each year, tens of thousands of them in Pennsylvania. This misfortune is not reserved for older, more capable teenagers; a full 42% of homeless children in this country are under the age of six. By fifth grade, at least 7% of all children in this country have spent time living in shelters or cars.

Homeless children are the most educationally at-risk student population. They are more likely to drop out of school than graduate and more likely than other students to become homeless as adults. Failing today’s homeless youth ensures another generation of underachievement and lost promise. What is more, school-enrollment policies can create insurmountable barriers for homeless students.

However, the federal government has tools to break down these barriers. The most important of those tools is the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, which requires schools, school districts, and other educational agencies to consider homeless children when determining enrollment policy. The act emphasizes that homeless youth have a right to the same services as other students, from enrollment to transportation to class selection. Homelessness alone is not a sufficient reason to exclude students from the mainstream school environment.

McKinney-Vento protects any child who lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence. This definition is broad enough to include many children and youth whose living situations might otherwise complicate their enrollment. It includes children who:

- are sharing housing due to loss of housing, economic hardship, or similar reason;

- are living in motels, hotels, or camping grounds due to lack of alternative accommodations;

- are living in emergency or transitional shelters;

- are living in cars, parks, public spaces, or substandard housing; or

- migrate between these and/or other circumstances.

The Carlynton lawsuit is the most significant legal precedent in this area of the law. It did much more than secure the right of a single family to send its children to school. Building on the work of individual school districts, it spurred the Pennsylvania Department of Education to change its policy on the educational rights of homeless children. According to the new policy, a school district where a child’s adult caregiver resides, where the child spends the greatest percentage of his or her time, or with a substantial connection to where a child receives shelter or stays overnight must accept that child’s enrollment.

Homeless families face a constant struggle, but it is a fight they can win if we collectively raise our consciousness. Far too many in our communities face homelessness, but we have an increasing array of institutions and laws ready to serve them. These institutions offer more than a meal and a bed; they offer services and support to help families confront the unexpected obstacles that inevitably accompany homelessness. The McKinney-Vento Act represents an important step in communities’ making the transition from merely tolerating homeless children to proactively meeting their needs and helping them to thrive.

As United States attorney, I know that the McKinney-Vento Act is more than a statute about education; it is about civil rights. Homeless children deserve equal protection and equal opportunity under the law, including the right to an equal education. A half-century after Brown v. Board of Education, securing equal educational opportunity remains all too difficult across the nation. Homeless children deserve the opportunity to be taught and to be tested, to learn and to be challenged. More than anything, they deserve to be students, fully participating members of their schools and communities.

Our work on behalf of homeless children is integral to the full body of our civil rights enforcement efforts. Joe Lagana and the Homeless Children’s Education Fund have been very successful in cultivating hope and opportunity for homeless children in Western Pennsylvania, but they are not alone. When they fight for the right to an education, they fight for rights guaranteed by the law of the United States of America, and all of us who have sworn to uphold it stand beside them.

Resources

The United States Attorney’s Office, Western District of Pennsylvania; Pittsburgh, PA ■ Homeless Children’s Education Fund; Pittsburgh, PA ■ Interfaith Hospitality Network Pittsburgh, PA ■ National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty; Washington, DC ■ Education Law Center; Newark, NJ.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The Historical Perspective—

Mothers’ Pensions

by Ethan G. Sribnick and Sara Johnsen

In 1905 George Rourke, a New York City maintenance worker, developed a kidney disease that forced him to stop working. Before that time George and his wife, Catherine, had provided for their five children, aged three months to seven years, by combining his earnings with the money Catherine made working part-time at home. When George became ill, though, medical expenses depleted their savings, and soon afterward, George died. Catherine, with young children and little job training, had few options to keep her family housed and fed; there were no cash welfare payments in New York, no food-stamp program, and no benefits for widows.

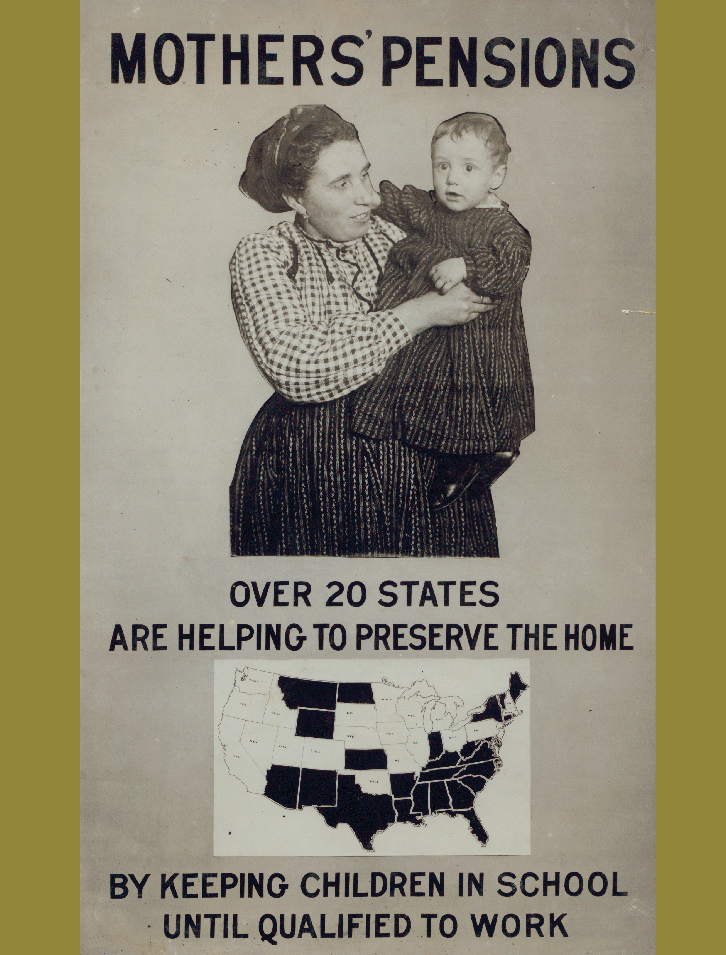

Between 1910 and 1930, 46 states responded to stories about single-mother families like Catherine Rourke’s by establishing mothers’ pensions, monthly cash stipends intended to help poor single mothers keep their families together. Mothers’ pensions served as a model for Aid to Dependent Children (ADC) in the federal Social Security Act of 1935 and became the model for welfare programs for the next 60 years. Today, 16 years after welfare reform mandated work requirements and time limits on benefit receipt, political rhetoric on welfare still echoes the debates that took place over a century ago. Should public assistance always be predicated on employment? How can society extend assistance to poor families without building “dependence”? Who deserves help?

This poster, including a photograph by Lewis Hine, appeared in a 1914 exhibit about child labor. Mothers’ pensions were part of a Progressive reform agenda that included campaigns against child labor and for women’s suffrage and labor protections. Courtesy of National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress.

These questions have shaped American policies toward the poor since Europeans arrived in North America and confronted the problem presented by the destitute families in their midst. When male wage earners died, were injured, or deserted their families, mothers struggled to support themselves and their children. Women in colonial cities could take work into their homes, but in a labor market with strict gender segregation a woman rarely earned enough to support an entire household. Families, therefore, often turned to public and private sources for support. Cities including New York levied taxes used specifically to take care of the poor, usually in one of four ways. Desperate families could receive “indoor relief” in the municipal poorhouse, where they would typically perform chores to earn their keep. Another option was “placing out,” a practice in which parents sent children into wealthier homes to work as servants or apprentices, leaving poor families with fewer children to provide for and offering children the opportunity to learn trades. A third option came about in the early 1800s, when congregate institutions were founded to care for poor, orphaned, or half-orphaned children. Some allowed families to place children in the institutions temporarily, until the children were old enough to find jobs and contribute wages to their families’ incomes.

The fourth and most common source of assistance, starting early in the colonial era, was “outdoor relief,” which granted food, coal, or small amounts of cash to families. Such aid was provided to the elderly, those too sick to work, and, at times, fathers who lost their jobs or were earning too little to support their families. Outdoor relief also became the primary public support for widowed and abandoned mothers whose families needed assistance.

This form of relief was attacked from the beginning. Efforts to outlaw outdoor relief started in Philadelphia as early as 1760 and in New York in 1820. Critics objected to outdoor aid primarily because they believed its existence acted as a disincentive to work. A New York City minister bemoaned cash assistance, which “deprived [recipients] of their feelings of honourable independence and self-respect.” Another observer in the 1820s leveled a more material criticism: “No poor law can be otherwise than injurious which interferes with the labor market, and this of America does so even now, by giving relief in aid of wages.” These criticisms were grounded in the misperception that recipients of outdoor aid were capable of supporting themselves through labor. In reality, most recipients of relief were either too old or sick to work or were single mothers unable to both supervise their children and earn enough to support their families.

By the 1870s most major cities had eliminated cash benefits from outdoor relief, further limiting the options for single mothers. The decreases in outdoor relief forced poor mothers to turn to private charity. Mothers who requested aid from organized charities were frequently subjected to extensive investigations of their housekeeping and parenting styles; interviews with their neighbors were designed to identify women with immoral or “intemperate” lifestyles. Charity combined with earnings helped many women keep their families intact, but those declared ineligible for assistance were frequently forced to place children in congregate homes. In 1894 more than 33,500 children in New York State lived in institutions. An 1890 study of institutions for children found that many residents had been committed by responsible parents who could not afford to raise them at home.