Publisher’s Note

Dear Reader,

We trust you will enjoy the Fall 2013 issue of UNCENSORED, which continues many of our regular features while exploring new avenues to discuss family poverty and homelessness. As always, we appreciate the interest of both new and returning readers.

This issue’s on the Homefront section includes excerpts from the Tackling Poverty panel discussion in early 2013. Tackling Poverty represents a collaboration between ICPH and the New York–based civic-journalism organization City Limits, aimed at engaging the community on the topic of poverty and homelessness, locally and nationally. For this issue’s On the Record section, professionals from California, Arizona, and Washington, D.C., speak to us about the fight against homelessness in those areas.

With students and teachers now fully engaged in the 2013–14 school year, we turn our attention to education, through three features exploring the learning process as it applies to homeless and other underprivileged children. “Girls Write Now” takes a look at a highly successful New York City program, one that pairs professional women writers and editors with often at-risk female high school students to enhance the girls’ writing skills. Maryland is the home of the Judy Centers, the topic of another feature, which examines those facilities’ efforts to bring together educational and family services under one roof for preschool-aged children and their parents. And we break new ground with “The Sanity Project,” which comprises heartbreaking and inspiring personal essays by a Michigan-based homeless education liaison.

In another departure, our Guest Voices column—a Web extra in this issue—cites the history of New York City public schools to make the case for enhanced sensitivity to the educational needs of children of immigrants.

In our ongoing discussion of the plight of poor and homeless families, we at UNCENSORED welcome your comments, questions, and suggestions.

Sincerely,

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, Publisher

President and CEO, Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Judy Centers and Community Schools:

Raising Student Achievement by Supporting Children and Their Families

by Lauren Blundin

Summer may bring the end of another school year for most kids, but not for those living in communities fortunate enough to have a Judy Center. All summer long this year, the Judy Center at Hilltop Elementary School in Glen Burnie, Maryland, hosted playgroups and learning parties for community children (birth through kindergarten) and their parents.

In late July families gathered at the Hilltop Judy Center for a science-themed playgroup. Some families sat in chairs while others curled up on the floor, listening to playgroup leader Nancy Garcia read a story about air. Children answered her questions eagerly and, after the story, ran to the tables to begin an air-related science experiment involving water, food coloring, and paper. There was a gentle hum of conversation in several languages as adults and children completed the experiment together. Garcia, who speaks English and Spanish, floated through the classroom giving advice and encouragement. After the experiment, the children moved into the classroom’s play area to listen to music and have fun with puppets and other toys.

Parents at a Judy Center help their children follow directions in order to complete a science experiment.

One mother, Lynn, learned about the playgroup through the Maryland Infants and Toddlers Program, a Judy Center partner that is providing speech services to her toddler, a girl. Lynn cradled her infant while her toddler played with other children. A former teacher turned stay-at-home mother, Lynn recognizes the value of this social interaction for her daughter as well as the academic component of the playgroup. “I like that the playgroup includes a circle time,” she says. “There are stories, and they talk about colors and shapes. It gives her an opportunity to listen and learn to focus.”

Brandy is another mother who is enthusiastic about the Judy Center. Her two-year-old loves coming to the playgroups and other activities. The Judy Center is located on the grounds of the elementary school, and Brandy’s son has been coming since birth. He already feels that he is part of the school, and Brandy says he can’t wait to start kindergarten.

Many parents and caregivers, including Brandy, have taken advantage of the opportunities for adults at the Judy Center. Brandy says she has learned a lot from the behavioral-interventions workshop. “It taught us different techniques to discipline,” she explains, “and it was also nice to sit and talk with other adults about behavioral challenges. You can know that ‘Hey, it’s not just me that is dealing with this!’” Her favorite course, though, was on ways to teach her son math. “We count candies together, and then sort them by color. We toss toys in a bucket and count them. I incorporate math into play at home now.”

Amy Beal is the coordinator of the Hilltop Judy Center. “We’re educating parents as well as the children,” she points out. “We’re showing them ways to interact with their young child, and teaching them about the ages and stages of early childhood.”

Playgroups are just one of the innumerable tools that Judy Centers use to support families. Stimulating early learning experiences for children and their caregivers is a hallmark of Maryland’s Judy Centers—known officially as the Judith P. Hoyer Early Child Care and Family Education Centers. Judith Hoyer, who died in 1997, was an educator who championed early intervention and family support for Maryland’s low-income communities. Her vision for providing both educational and community services under one roof, where specialists could collaborate on different programs for children, was realized in 1993, with the opening of the Early Childhood and Family Center in Adelphi, Maryland. After Judith Hoyer’s death, her husband, U.S. representative and current Democratic whip Steny Hoyer, led the charge to fund Judy Centers throughout the state. In May 2000 that funding became part of Maryland law.

Maryland’s Focus on Early Intervention and Support for Children and Families

Judy Centers are targeted to low-income areas. They serve approximately 12,000 young children and their families who live in the communities surrounding 39 elementary schools in Maryland—schools in districts that qualify for funding from the federal Title I program. (Part of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, Title I provides extra instruction for students at risk of failing to meet states’ academic performance standards. While the Judy Centers do not receive Title I funding, which is meant for school-age children, Title I status serves as a measure of poverty in the school community and as a guide for the location of Judy Centers.)

Most Judy Centers are open year-round, seven to 12 hours a day—usually closer to 12—providing educational opportunities and support to families and children. The overall goal of the Judy Centers is to increase the number of children who enter Maryland schools ready to learn.

Judy Centers sometimes provide services directly, such as with the Hilltop Center playgroup, but many offerings are through collaborations with community-based agencies, organizations, and businesses. For example, a local church may work with a Judy Center to provide clothing for families who need it. In one partnership, Northrop Grumman, a defense-contracting company, teamed with the Wolf Trap Foundation for the Performing Arts to bring the “STEM through the Arts” program to some Judy Centers—“STEM” referring to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. One Judy Center coordinated with its partner agencies (which include child and human services agencies) to hold an information session for parents on the kinds of benefits for which families may qualify. While Judy Centers are physically located in schools, the sizes of those locations—and thus the number of people they can reach—vary. Much of the centers’ effectiveness comes through their partnerships.

Power through Partnerships

“Each Judy Center has a formalized partnership with the local agencies, organizations, and businesses in the community,” according to Cheryl DeAtley, Judy Center partnerships specialist at the Maryland State Department of Education (DOE). The number of partners varies, depending on whether the Judy Center is in an urban or rural area and on the number of agencies and businesses in that area. Partnerships range from ten to 30 agencies and organizations. Judy Center coordinators and partners meet at least monthly to discuss upcoming activities and the changing needs of the families they serve. “Our goal with our partnerships,” DeAtley explains, “is to have someone to turn to for every issue a family can come to us with.”

Services that the Judy Centers commonly arrange or provide directly include medical and dental care, adult education, parenting classes, and identification of early intervention services for children with special needs. Families requiring intensive support services receive home visits by Judy Center staff members. Judy Centers will also help families meet their most basic needs, such as for food and clothing.

A mother helps her older child with an art project.

Baltimore’s DRU Judy Center at John Eager Howard Elementary School recognized that its children and families needed help obtaining food. (“DRU” is an acronym based on the nearby communities of Druid Park, Reservoir Hill, and Upland. The main DRU center, at John Eager Howard, has two satellites—at the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and Furman Templeton elementary schools.) Through a partnership with the Maryland Food Bank, the Judy Center has provided groceries to parents of the children it serves and to the larger school community. Parents are encouraged but not required to volunteer at the school in exchange for food.

On a Thursday in July of this year, a Judy Center father arrived at John Eager Howard to supervise the unloading of the Maryland Food Bank truck. School was out of session, but the building was bustling with children, teachers, and volunteers. A group of teens from the Baltimore City youth workers’ program took a break from helping in the summer-camp classrooms to help unload the boxes of food. A mother and her child arrived to help sort the food and pack bags to be distributed to other parents and community members.

Meeting Social and Emotional Needs

At the Judy Centers, a critical element of preparing children for kindergarten is meeting the mental health, social, and emotional needs of the boys and girls and their families. Through its partnership with the University of Maryland’s Secure Starts at the Taghi Modarressi Center for Infant Study (CIS), the DRU Judy Center at John Eager Howard Elementary School benefits from the services of Cecelia Parker, a full-time, on-site mental health consultant.

“I’m here every day,” Parker says. “I concentrate on strengthening families.” She teaches children social skills such as making friends and resolving conflicts. She also works with children individually and in small groups to address specific behavioral or emotional problems. In monthly workshops, Parker provides parents with information on a broad range of topics—everything from meeting children’s social and emotional needs to managing household finances.

“I also provide them [with] coping resources,” Parker adds, “because most of our families live in areas where they are constantly affected by different traumas. And if parents need therapeutic services, they can also see me during my evening office hours.” DRU Judy Center coordinator Cathy Frazier applauds the University of Maryland CIS for developing the full-time mental health specialist model with Judy Centers. “After all,” Frazier says, “mental health issues can come up any time, not just on a Tuesday or a Thursday”—an allusion to the sporadic availability of mental health specialists in most public schools.

Expanding the School Day

Prompt access to services or referrals is another feature of Judy Centers. The centers provide or coordinate a number of programs to expand the school day and year for children. At the DRU Judy Center, for example, resources such as drop-in art classes, a computer lab, and after-school care and activities abound through a partner, the John Eager Howard Recreation Center. The DRU Judy Center has also started providing special summer camps for entering preschoolers and entering kindergartners. The camps are taught by John Eager Howard’s preschool and kindergarten teachers, so the children will start school in the fall already comfortable with their teachers and familiar with the classroom environment and routines.

The People Make the Program

“The people really make Judy Centers work,” DeAtley says. “The program coordinators we’ve put in place, the principals who are so supportive and understand the value of early intervention, our partners and parents—the people make it successful, because there isn’t a whole lot of money involved.”

A short conversation between Gale Carter, assistant principal at John Eager Howard Elementary, and DRU Judy Center coordinator Frazier captures the importance of having the support and active participation of everyone connected with the children—parents, teachers, and community members alike. “We go door to door in our community to make sure parents know what is available,” Carter says. “Early learning is a passion for me.”

Amy Beal, coordinator of the Judy Center at Hilltop Elementary School, holds balloons that will be given to children as they leave their weekly playgroup.

“And that’s really important,” Frazier adds, referring to support and commitment from the school administration. “You need that top-down understanding of the importance and power of early support and intervention.” The field of early childhood education is based on research showing that children who have high-quality care and early learning experiences are more likely to enter kindergarten prepared to learn. Recent studies have also pointed to the impressive lifelong benefits of quality early childhood education. Researcher Lawrence Schweinhart analyzed data from the graduates of the High/Scope Perry Preschool program, which serves Michigan three- and four-year-olds living in poverty and at risk of academic failure. Even at age 40, former participants demonstrated the positive effects of the program, as Schweinhart explained in a 2004 study: adults who at age three or four had attended the program were more likely to be employed, had higher incomes, had experienced fewer run-ins with the law, and had received more schooling than a control group of children who did not take part in similar programs.

Making the Most of Flat Funding

Although the number of Judy Centers has increased over the years, state funding for each center has not. Each one receives approximately $322,000 a year, an amount virtually unchanged since the program began. “Funding is flat, but we think of creative ways to fund programs,” says Frazier. By harnessing the services and capabilities of their partners, Judy Centers make effective use of the money they do receive.

“Every budget I review is very different,” DeAtley explains. “The needs of rural Garrett County in Western Maryland are different from those in more urban areas like Prince George’s County and Montgomery County. Some centers have to put a significant amount of money into behavioral and mental health interventions, while others hardly have a need for that. Some centers are focused on English Language Learners and parents learning English. There’s little restriction in what centers can use funding for, which is great, because they really need that flexibility.”

Judy Centers Get Results

Maryland’s Judy Centers are skillful at getting good results from limited funding. The most recent data from the Maryland DOE show that children who attend Judy Centers are more likely to be assessed as fully ready for kindergarten (86 percent) than their peers who do not benefit from the centers’ programs or services (79 percent). This increased readiness is a testament to the Judy Centers’ ability to support their diverse populations. For example, Judy Centers serve a much higher percentage of children who are receiving special services (including special education, English Language Learners services, Free and Reduced Price Meals, or a combination of those) than the state as a whole: in Maryland, 53 percent of all entering kindergartners received special services, compared with 71 percent of Judy Center kindergartners. These data underscore the value and importance of early support for children and families and the important role Judy Centers play in early identification of and intervention for students with special needs.

“Sometimes it takes a whole village to improve a child’s readiness for kindergarten,” says Lillian Lowery, Maryland state superintendent of schools. “The Judy Centers bring that village together in one location. They have been an unqualified success.”

Despite their success, Judy Centers remain unique to Maryland in their narrow focus on children from birth through age five and their families living in Title 1 school communities. On the other hand, the partnership strategy and the focus on supporting the entire family have also been employed with success in the form of community schools. In fact, one of the strongest advocates of community schools is Congressman Hoyer, who has called for a Judy Center–like approach to serving students in elementary school through high school.

The Rise of Full-Service Community Schools

In each Congress since 2004, Congressman Hoyer has introduced legislation for the Full-Service Community Schools Act in the House. Senator Ben Nelson has introduced companion bills in the Senate. The legislation would authorize a U.S. Department of Education grant program to expand full-service community schools across the U.S. While the grant program has not been authorized, over $40 million has been appropriated since 2008 to fund 21 community-school projects around the country.

“Full-service community schools tap into community resources to provide students and their families with access to a wide range of services that improve student achievement and ensure families are prepared to support learning,” Congressman Hoyer says. “In Maryland, Judy Centers have proven to be effective when it comes to the integration of education, health and social service delivery, and this model should be a key part of our national efforts to improve educational outcomes for students and expand middle-class opportunity.”

Judy Centers emphasize parent participation during playgroups.

The types of services coordinated at full-service community schools include remedial education and academic enrichment, parental involvement and family literacy, mentoring and other youth development, mental health and counseling services, early childhood education, programs for truant, suspended, or expelled students, primary health and dental care, job training and career-counseling services, and nutrition services.

Matthew Whooley of Indianapolis is responsible for the care of his nephew, who attends George Washington Community High School (GWCHS); originally George Washington High School, it closed in 1995 and reopened as GWCHS in 2001. Whooley also has three children who attend Stephen Foster Elementary School, or School 67, a feeder school for GWCHS. “GWCHS has allowed me to become a fully involved parent [who] is in the school on a daily basis … ,” Whooley says. “I have found that the community school keeps parents more involved with teachers, coaches and administrators than the regular school model does. It inspires a more family-like atmosphere in the building and throughout the neighborhoods. A large advantage to having community partners is that our children can see that the entire community is supporting them and their education. It is such an amazing motivational tool for our children. It gives [me] as a parent reassurance that raising my children’s education is a team effort. … Being able to count on the local businesses and other community entities to give our children extra support and opportunities makes it easier as parents. In my opinion every school in the country should be a community school.”

Community Schools: A National Snapshot

The Full-Service Community Schools Act builds on an existing community-schools movement that has been growing for more than 20 years. The Coalition for Community Schools (CCS), a research and advocacy organization operating under the Institute for Educational Leadership in Washington, D.C., has been advocating for community schools since 1997. It is difficult to obtain an exact count of community schools because there is no one formal model for such a school. However, CCS’s director, Martin Blank, estimates that there are as many as 5,000 institutions in 65 locations that self-identify as such and operate under a community-schools approach.

Taking advantage of existing resources to maximize services to children and families is a characteristic of both Judy Centers and community schools. The strategy is paying off.

A playgroup participant contemplates whether to keep his balloon or conduct an experiment by releasing it to see what will happen.

The Children’s Aid Society (CAS) has a long-standing community-schools initiative that is thriving in New York City. Since 1992 the CAS has partnered with the New York City Department of Education in 16 community schools. A recent CAS report found that “Children’s Aid community schools produce better student and teacher attendance, increased grade retention, more appropriate referrals to special education services, improved test scores and higher parent involvement than similar schools.”

Like CAS schools, community schools across the U.S. are reporting positive results as well. A recent Coalition for Community Schools review of (self-identified) community schools around the nation found that these institutions are seeing significantly improved outcomes for students in a number of areas, with children entering school fully prepared to learn; developing better work habits and attitudes toward learning; showing improved grades and test scores; earning more high school credits; and graduating from high school.

Here are just a few of the many success stories uncovered by CCS:

■ In schools most successfully implementing the Tulsa Area Community Schools Initiative, students have significantly outperformed their peers in state math and reading exams (by 32 points and 19 points, respectively).

■ Since the implementation of Community Learning Centers, in 2000, Cincinnati high school graduation rates have increased from 51 percent to over 80 percent.

■ Students in seven high schools in Portland, Oregon’s Schools Uniting Neighborhoods (SUN) community-schools initiative made a number of impressive achievements, including increasing the average number of credits earned per year from 5.1 to 6.8, a pace that puts SUN students on track to graduate.

Community Schools’ Outlook for the Future

Judy Centers and community schools are effective in using limited resources to obtain positive results among low-income communities and at-risk student populations. Several studies have concluded that the community-schools approach provides a remarkably high return on investment. The Finance Project, a Washington, D.C.–based nonprofit group, investigated the social return on investment (SROI) of two of the CAS’s community schools in the Washington Heights area of New York City; its finding was that every dollar spent returned $10.30 and $14.80, respectively, of social value, or the value generated through an investment in the schools. Other studies have reached similar conclusions.

Schools are struggling to meet ever-increasing standards for student achievement, even as their populations continue to grow more diverse and complex. Together, the Judy Center approach to early childhood education and family support, and the community-schools approach to supporting older children and families, could provide educators with a solution to their challenge.

Resources

Hilltop Elementary School; Glen Burnie, MD ■ Maryland Infants and Toddlers Program; Baltimore, MD ■ Judith P. Hoyer Early Child Care and Family Education Centers; Baltimore, MD ■ Northrop Grumman; Falls Church, VA ■ Wolf Trap Foundation for the Performing Arts; Vienna, VA ■ Maryland State Department of Education; Baltimore, MD ■ John Eager Howard Elementary School; Baltimore, MD ■ Maryland Food Bank; Baltimore, MD ■ University of Maryland Secure Starts at the Taghi Modarressi Center for Infant Study; Baltimore, MD ■ Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Elementary School; Baltimore, MD ■ Furman Templeton Elementary School; Baltimore, MD ■ Coalition for Community Schools; Washington, DC ■ Institute for Educational Leadership; Washington, DC ■ Children’s Aid Society; New York, NY ■ New York City Department of Education; New York, NY ■ Schools Uniting Neighborhoods; Portland, OR ■ Finance Project; Washington, DC.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The Sanity Project:

Essays by a Michigan-Based Homeless Education Liaison

by Beth McCullough

For over a decade Beth McCullough has served as the homeless education liaison for Adrian Public Schools, in Michigan, and as the homeless education coordinator for Michigan’s Lenawee County. Her “mantra,” she says, is “Education is the answer,” and as she informed UNCENSORED, she “can be found crawling under porches to find homeless youth and visiting aluminum sheds to rescue children who are using a blue tarp as a blanket.” McCullough has written 200-plus short essays as part of what she calls The Sanity Project: musings and observations on the people she has met in her work, the dire situations they face, and the mingled heartbreak and inspiration she finds in their stories. McCullough felt inspired to undertake the project after her supervisor asked her one day, given the stress that her work involves, “How are you going to keep doing this job?” Shortly afterward she began writing the essays, which helped her to “keep sane in the job so I could keep going,” and e-mailing them weekly to four colleagues. Those women shared McCullough’s writing with others in the field, who passed them on to still others—until the essays began to be included in state conferences on homeless education and McCullough started to hear her own stories being repeated back to her.

Following are seven essays from The Sanity Project:

I have looked for success this week. It is Friday and I am still looking. Failures seem plentiful. A mother who is a long-haul trucker refused to let her daughter, who should have been a second-grader, stay with the grandmother so the girl could attend school. The mother said she was “homeschooling” her daughter. The girl can’t read.

One of the unaccompanied youth I am working with said he would just go to jail because he was tired of being on probation. I told him there was no high school in jail. He shrugged. He said he would get three meals a day there and gets only two meals a day at school. He loves music, and I told him he couldn’t play his trumpet in jail. He said he had to think about that one. I watched him walk out of school and disappear amongst the tall piles of dirty snow.

The Michigan Department of Education came out with guidelines that make it very, very difficult to use special education buses for homeless students. In my county the guidelines take away that option altogether.

So at noon on Friday, I have to look a little closer. I gave a coat to a high school student yesterday. He was wearing two sweatshirts, but it was below zero outside, so he was still cold. He was pretty excited about the coat. He walks a lot. His attendance continues to be spotty, but he loves his coat.

I certainly had a good smile today. When I dropped off a bag of mittens at the shelter, I saw two toddlers playing king of the hill on top of a snow pile. The one little guy made it to the top of the six-foot-tall mountain and raised his arms in the air like Rocky. I saw the snow hill as dirty. He saw it as a victory. The mundane became his challenge and his success.

I take for granted so many of the successes of the week. They are just part of the day-in-and-day-out happenings in the job of a homeless education liaison. These successes are like the piles of snow that are the accumulation of many snows. I just take them for granted and forget to climb to the top and throw my arms in the air. Here are just a few of the successes of the week:

One of my unaccompanied youth just received a $40,000 scholarship to the University of Michigan. She has a 4.2 GPA and will be one of our valedictorians this year. I have been trying to figure out how to get her a laptop computer and forgot to celebrate her amazing scholarship.

A 19-year-old student just made up the work he needed to finish in order to graduate this year. He has learning difficulties, so it has been a long and difficult road for him. His family has lived in at least six different places this school year. I need to call the organization that rents caps and gowns because now he will need one. Where did I put that card?

The to-do list is long, and the struggles continue, but I do need to look up and see the many victories. I am surrounded by amazing kids crawling to the top of the dirty snow pile. We all need to dance like Rocky and throw our arms up in the air. Graduation is not just one success, but the result of a thousand successes along the way. Maybe “Pomp and Circumstance” at graduation should be replaced by the theme from Rocky. //

A third-grade boy came into my office with his mother. He had not been enrolled in any school yet. I met the mother when I was at a motel, visiting another family. I think I need office hours at the Motel 6. The mother and I were filling out paperwork, calling the school to remind them that we could enroll this student even without the birth certificate that had been thrown out during the eviction. I would order another one.

The young student sat quietly in the corner, going through a box of Beanie Babies people had donated. He picked out about ten. I almost said, “Maybe you should just pick two,” but they had been given to me freely. Why would I ration them out? The boy stood up with an armful of the little critters. His mother stopped him at my office door. She said, “What are you going to do with all of those?”

The boy replied, “These are the Beanie Babies that Dad would never buy us when we went to the flea market. These are the expensive ones. I am going to sell these and buy a house for us.” Homeless children take on more than we know. //

I was working with a homeless unaccompanied youth. He was a 17-year-old high school senior and varsity football player on track to graduate. His mother was a drug addict and an alcoholic. On nights when she became violent, he would find another place to sleep. We found a host home for him so he would always have a place to sleep and have some stability in his senior year.

He came to my office on a Thursday with a heavy decision to make. “My mom is really sick. She called last night.” He had disclosed to me earlier that sometimes his mother would get sick from the drugs, and he would stay with her to make sure she didn’t need the ER or go into convulsions or choke on her vomit. This student saved his mother’s life on at least one occasion.

He continued to explain his predicament: “I should go back home and take care of her. But I have a football game tomorrow. I really want to play football. But my mom could die without me.” We talked for a while and he came to the following realization: “Somewhere in her she wants to be a good mom. She must want the best for me. If my mom could be the mom she wants to be, she would want me to do the best for me.”

He played football on Friday night. I was there screaming for him like a mom, or like a homeless liaison. At one point I made my way down to the rail, and he came over to me and said, “It is good to play football.” I agreed, and he gave me a fist bump. I hope his host home knows how to wash out grass stains. //

Our new governor gave the “State of the State” address last night. He suggested that we start thinking of education as “P to 20” rather than “K to 12.” He was referring to “preschool through college” rather than the more common “kindergarten through 12th grade.” It reminded me of this story from a tutor we employ for the local domestic-violence shelter.

The tutor had gone through the shelter’s training program and was versed in its policies, rules, and procedures. Then came her first day at the shelter. It was eye-opening for her. She was greeted by a three-year-old carrying a container of diaper wipes. He held it up to her and asked, “Please?” His diaper was full and apparently uncomfortable. The tutor found a shelter worker, who found the boy’s mother, who changed his diaper. The mother apologized to the tutor and explained that she was trying to make the diapers go as far as possible because she didn’t have many and had no funds to get more.

I met with the tutor after her first week, and she told me that story. She also asked, “Is it OK if I work with toddlers?” I told her that I would prefer she not change their diapers but that she could certainly offer preschool activities for them. She ended up prioritizing homework help for school-age children but always had preschool activities in her “bag of tricks,” as she never knew which children were going to be in the shelter when she arrived. She also performed an incredible service for moms when she explained that homeless children had priority when enrolling in Head Start. Children who had been on a waiting list were now being placed in Head Start due to their homeless status.

The tutor was also able to follow up with the three-year-old who had greeted her on her first day in the shelter. On one of her return trips, she sat down to read a book to a small group of toddlers. The little guy who had greeted her snuggled up close to her. Halfway through the book, his mother asked if she could sit in and listen too. The tutor gave her a smile and nodded yes, and the mother joined the group.

After the small group had dispersed, the mother told the tutor how much she loved listening to books, as her own mother had read to her when she was little. The tutor asked if the mother needed books to read to her child. After a few moments of hesitation, the mother disclosed that she could not read very well. The tutor explained how the mother could tell her toddler a story just by using the pictures in the children’s books. With the next group of children, the tutor demonstrated this idea. The tutor contacted me to find a referral for an adult-literacy program. (We have a great one in our town.) She also offered to help the mother with the Head Start application.

In the first half of the school year, our tutor worked with 47 children at that shelter. Twenty-seven of them were preschool-age but not in preschool. They may spend the entire day at the shelter in the whirl of women and children in crisis. It is a common shelter practice for one mom to babysit for another so little kids are not hauled around for apartment hunting and long waits at the Department of Human Services. Even when moms get out of the shelter for a few hours a day, these children may not get out at all. The tutor may be the highlight of their day. She told me, “I just want to make a difference.” I told her, “You are the difference!” In the field of homeless education, children are listed in reports to the Department of Education as “others served.” I think we would all agree they are well worth serving. //

He was soft-spoken. He made eye contact briefly and then looked at his hands in his lap. He said, “I’m sorry, I have a question. But … umm … I’m sorry. Wait … I mean … I’m sorry.” He took a deep breath and tried again: “I’m sorry. Could someone … I mean … I don’t eat a lot. I don’t eat. I’m sorry.”

“When was the last time you ate?” I asked.

“I’m sorry. I just … I just … I ate Friday at here, at school. I’m sorry,” he said. It was Monday morning. We quickly provided him with breakfast. I made arrangements for an outreach worker from the Runaway and Homeless Youth program to take him shopping with gift certificates I had for a local grocery store.

The application for food assistance from the Department of Human Services was a challenge. The woman helping him with the paperwork asked, “Doesn’t your mother give you any money?” He looked down and shook his head no. He didn’t have a penny on him. The woman put down “zero” as his income. That prompted a DHS worker to call him later in the day. He told me about it.

The worker wanted to know where he lived. He has permission to sleep on the couch of a friend of a friend. That gentleman is not at home most of the time and does not eat there. “How do you pay your bills with no income?” the worker asked.

“I’m sorry. I don’t have bills,” he said.

“Then who pays the bills where you live?”

“The guy who rents the place pays them.”

“He should feed you,” the worker said. “Where is your mother?” He told her his mother lives with one of her friends. “Then she should feed you too. You have two different people who can provide food for you,” she said. Did she really expect this kid to say his mother was committing welfare fraud because she had not reported asking him to leave and was not providing food for him?

I gave another grocery coupon to the outreach worker to take him shopping again.

“I’m sorry,” he said. Reading between the lines, I heard so much in his apologies. I couldn’t read his mind, but what I heard sounded something like this:

“I am sorry to take up your time. I am sorry I don’t know the answers to the questions I have. I am sorry my mom can’t take care of me right now and I don’t know where my dad is. I am sorry I don’t want to tell you of the loneliness I feel. I am sorry I don’t fit into your boxes on your forms and the ‘other’ line isn’t big enough to describe me.

“I am sorry nobody wants me or wants to feed me. Please don’t ask me why. I don’t know. I am hungry. I am hurting. I am scared but I am still here. I am sorry if that bothers you. I am not sure I believe I am worth all the bother, but I want to believe I am. I want to believe I am worth an education. Maybe you don’t think so. I’m sorry. You are wrong.”

I read this to him. He smiled like he had been caught and then broke out into a full laugh. His laugh is not soft, and it made me laugh too. I asked if I could send out what I had written to help others understand the difficulties he faced. He said, “Send it.” //

I hope that when I re-read this in years to come, I have to work very hard to remember what all the talk of the “fiscal cliff” was about. Presently, every news broadcast starts with those words. The idea is that without some precision cutting, the federal budget will automatically have massive cuts across the board. Although I hear the panic in the voices of a number of lawmakers, citizens, analysts, and newscasters, I can’t help but wonder if they have looked over the edge of the cliff lately.

Come with me to the edge, lie flat on the ground so you don’t fall off the cliff yourself, and look down at what many believe will be catastrophic cuts. If we get past the dizziness from looking at the drop and focus, we can see people holding on to bits of roots, branches, and rocky landings. Maybe there is a small tree that tried to grow out from the cliff several feet down, but it has been stripped bare of leaves as people grab on to anything they can in the fall.

What does that really mean? It means that our county has fewer Section 8 vouchers than it did ten years ago, despite a 63 percent increase in homelessness. There are over 1,000 families on the waiting list. There hasn’t been a new voucher added in 18 months! Why are they still taking applications? Those families have already fallen off the cliff and are hanging onto a branch, sure that help is on the way.

It means that the emergency funding our county normally receives went from $56,000 two years ago to $16,000 this year. Those funds are used for utility assistance, rental assistance, and food. There on the rocky landing is a family who lost their apartment because of a utility shutoff. If you can’t heat it, you can’t live there. It means that local charities are struggling to supply emergency food rather than funding programs like Roadmap to Graduation. Two years ago we had 13 in that program. We presently have two and had to decide today which student would receive the last slot, as we have funding for only one more. So there, hanging onto bits of root on the side of the cliff, is a 17-year-old.

Yesterday over 2,500 people protested in the rotunda of the capitol building in Lansing over the “right to work” bill, which will cripple unions. It will be signed into law next week. Next up are three bills that will drastically change school funding in Michigan. It will leave many traditional public schools with the students whom charter schools can reject. I can’t help but remember my Intro to Political Science class and Brown vs. the Board of Education. “Separate is not equal,” they said, but we may lose that lesson. Walking into work today, I literally shook my head like I had water in my ears.

I was just trying to shake off the panic of the cliff, the panic of the end of a way of life in Michigan, and the panic from the three work e-mails I read before I made it to my car to come to the office.

I helped make a decision today about which student will receive the remaining slot for the Roadmap program. Lying over the edge of the cliff, looking at the sea of people clinging below, I can grab the hand of one kid and pull. If the nation goes flying off this cliff like Thelma and Louise, I hope I am still here, grabbing the hand, the wrist, the arm of a kid to pull her up. If you see me down there, please do the same. //

A few times a year, I go into the woods where I know a group of homeless individuals camp out. I go to make sure there are no school-age teens who want to go back to school. On one occasion I was surprised to find a mother with a second-grade daughter. She told me the shelter was full. I told her I could help. I had to find a place for them to sleep that night or call Child Protective Services.

I asked her to come with me to my office. “Can I go?” said a man standing next to her. He was dirty and looked thin, despite the layers of clothes he had on. His hair was in knots. He wore a torn dark blue stocking cap and smelled like a wet dog.

I looked at the mother and said, “It is up to you. Is he with you?”

She said, “Yeah, he is a friend. He can come along.”

On the walk to the car, I asked their names, and the man took his hat off and pulled his bangs aside. The tattoo on his forehead read “666.” “Just call me Satan,” he said.

I stopped walking. “That is not the name your mama gave you,” I said. He smiled. He knew I wasn’t afraid of him. He put his hat back on and looked sheepish, like a little boy caught in a lie. The mother with us told me his name was James.

Back at my office I made some phone calls and got permission for the mother and child to stay on a couch at the shelter. I arranged transportation to school and gave them school supplies, shampoo, soap, deodorant, and new coats. I looked at James. It was cold out, and James was wearing two hooded sweatshirts with a white dress shirt underneath. It looked like he had tried to fold the collar of the dress shirt over the tops of the sweatshirts. “Do you want a coat, James?” I asked.

“Yes ma’am, I would really like a coat,” he said. I smiled. His tone was so different from when he introduced himself as Satan. I found a heavy down coat for him as well as some new socks, mittens, and a new hat. He was grateful. I dropped the mother and child off at the shelter and James off at the soup kitchen.

When he got out of my car, he smoothed out his new coat and smiled at me. “Thank you very much, ma’am. You are a good woman,” he said.

I offered him my hand and said, “It is good to meet you, James.” He shook my hand and nodded.

Two weeks later James was sitting outside my office at 7:00 a.m., waiting for me to come to work. He was wearing the coat I had given him and had brought a mother and her middle-school son. “Ma’am,” he said, “the woods is no place for these young people. I told them you could help them. I let the boy sleep with my dog. It made it really cold for me, but the boy needed to keep warm so I let Rusty sleep with him.”

“Thank you, James,” I said, unlocking my office door. I helped the mother and son find a place, made some arrangements, and gave them some supplies. James didn’t ask for a thing. He sat quietly in the corner and picked up a book out of a box of discarded library books. I told him he was welcome to take a few. He took the one he was reading and another, both Stephen King novels.

When I dropped him off at the soup kitchen, I said, “James, when you are ready to get that tattoo off your forehead, let me know. I think I could find a doctor willing to help you with that.” He laughed and told me he would think about it.

I saw James three other times before he left town for parts unknown. Rusty stayed in the woods waiting for his master to return. The other homeless people there fed him. //

Resources

Adrian Public Schools; Adrian, MI ■ Lenawee County, Michigan; Adrian, MI ■ Michigan Department of Education; Lansing, MI ■ University of Michigan; Ann Arbor, MI ■ Head Start; Washington, DC.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Girls Write Now:

A New York City After-School Program Pairs Women Mentors with Underprivileged Teen Female Writers

by Suzan Sherman

Back in 1998, when Maya Nussbaum was just 21 years old, she conceived of Girls Write Now (GWN) as a program to serve underprivileged New York City high school girls with a passion for writing. The mission of Girls Write Now is a seemingly simple one and hasn’t changed at all in the organization’s 15-year history: empower girls by pairing them with professional women writers and editors who serve as their mentors; have the mentors and mentees meet once a week to discuss writing and anything else that bubbles to the surface; then watch what happens.

“At around the ninth or tenth grade, you’re becoming developmentally awakened,” Nussbaum says at the offices of Girls Write Now, in Manhattan’s Garment District. The walls behind her desk are lined with books, many penned by women who serve as GWN mentors on a volunteer basis. “I was one of the lucky ones who had people all around me—supportive parents and teachers who opened up for me what was possible,” Nussbaum says. Along with her devoted ten-person staff and cadre of 150 active mentors, GWN has achieved an astounding success rate in a city where just over 60 percent of students graduate from high school. By contrast, 100 percent of GWN-mentored girls graduate, and even more impressively, all of them have gone on to college. This remarkable record has not gone unnoticed: the White House has twice recognized GWN as one of the best after-school programs in the nation. To date, GWN has helped more than 4,500 girls learn that it is possible to “write their way to a better future.”

Mentee Tema Regist reads from her work.

Starting small, GWN was hatched in Nussbaum’s living room when she was not much older than the girls her organization would come to serve. While in the throes of finishing her undergraduate studies in creative writing at Columbia University, Nussbaum experienced a paralyzing bout of writer’s block, which became part of the seed for the startup. “I wanted to break down the myth of the isolated writer—and so I harnessed my energy in another way, and proved that you can get help with the creative process,” she says. For six years, while working by day as an art gallery director, she ran GWN on the side, but when GWN was awarded institutional grant funding, she felt inspired to commit to the organization full-time. The following year GWN subleased its first office space from Teachers & Writers Collaborative. One of Girls Write Now’s earliest funders was the Brooklyn Community Foundation (formerly the Independence Community Foundation), which continues to provide support. The program is also currently supported by donors and foundation partners including the Digital Media Learning Fund in the New York Community Trust, the Pinkerton Foundation, Youth I.N.C. (Improving Nonprofits for Children), the National Endowment for the Arts, and the New York Women’s Foundation, as well as a long list of individual donors.

Nussbaum insists that any and all of GWN’s achievements result from the efforts of her highly accomplished group of volunteers. Those include the award-winning novelists Emma Straub, Alix Kates Shulman, and Alice Walker as well as editors who work for such top-tier publications as the New York Times and the New Yorker, who serve not only as mentors but also as board members, guest speakers, and supporters. The application process for becoming a mentor is rigorous. In addition to submitting a résumé and two writing samples, potential mentors must fill out an in-depth application and answer questions including “What would you like to accomplish working for Girls Write Now?” and “What are some of the challenges you anticipate encountering as a mentor, and how might you address those challenges?” Asked how she manages to get such busy, successful women involved in her organization, Nussbaum explains, “You’ve got to give them a stake in what they’re doing—we’ve got a staff of ten and a million-dollar budget, but the fuel of this organization is the volunteers. This was always a team effort of bringing women together who want to give back.”

Girls Write Now founder and executive director Maya Nussbaum (left), with mentee Tina Gao, receives the President’s Committee award on behalf of her organization from First Lady Michelle Obama at the White House.

Of even greater concern to Nussbaum is creating a sense of accountability for the girls, many of whom have lacked strong role models. “Excellence is a big value for the organization. GWN sets the bar high and in turn we expect the girls to do the same,” Nussbaum states plainly.

Sixty-six percent of the girls GWN mentors come from families at or below the poverty level, and 20 percent are from immigrant populations. Ninety percent are identified as high-need—those who are at risk, for a variety of reasons, of failing to graduate.

Using Their Voices

In the process of working with their mentors, girls learn that writing and editing can be marketable skills that might be used for professional careers, as well as personal tools for self-expression and empowerment. Besides the weekly one-on-one mentor/mentee meetings that run throughout the academic year, girls are required to attend various workshops, including “dorkshops,” where InDesign—a computer-design program commonly used in book and magazine publishing—is taught by industry professionals. GWN also offers free college-prep workshops, which are open to all New York City high school girls. The academic year concludes with a public reading series, in which the girls read aloud from their best work. For the majority this is their first time speaking in front of an audience—and an important milestone in using not only their words but also their voices to express themselves.

One recent GWN reading, sponsored by Ms. magazine, took place in the auditorium of the swank SoHo-based offices of Scholastic, the children’s and young-adult publisher of notable books including the U.S. editions of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter novels. The auditorium, which seats over 300, was packed to capacity, with people spilling into the aisles. A buzz of excitement was in the air as the reading was about to begin. Gloria Steinem, the famed feminist, was scheduled to serve as the guest speaker but had to cancel at the last minute, so Marcia Ann Gillespie—the former editor in chief of Essence and Ms. magazines—stepped up to provide a moving speech directed at the girls. “My great-grandmother,” she told them, “was a slave. Writing is the thing that we take for granted—that we can speak our truths and get in people’s faces, but it’s a privilege that so many women in this world still don’t have. I get to do what my great-grandmother didn’t get to do by being able to write.”

Mentee Karla Kim (right) shares her work with fellow mentee Emily Ramirez backstage before a Girls Write Now reading.

Two recent GWN graduates served as emcees for the evening; poised and confident, they said that what they learned through GWN will remain with them for the rest of their lives. Both now attend private, out-of-state liberal arts colleges. And then, one by one, the girls from the 2012–13 class walked onto the stage. Standing in front of the microphone with bright lights shining down on them, they addressed serious subjects. One girl read about walking past people drinking and taking drugs on her street corner and wanting to do better than that for herself; another read a poem about war-torn Palestine, where a mother tells her son to flee their country for a better life. A mentor and mentee read together about their shared love for their fathers—one an immigrant, the other with only an eighth-grade education. One after another, the girls moved their audience, their stories and observations sprinkled with such phrases as “Words change worlds” and “Writing is always in progress; we are always in progress.”

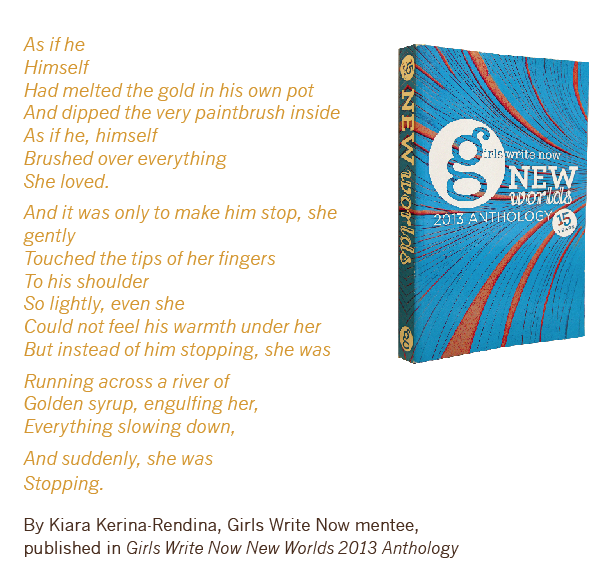

After the reading the audience emptied into the reception area, where a series of blue books had been stacked and fanned into table displays. Every year GWN publishes a themed collection of writings by mentees and mentors, this year’s theme being “New Worlds.” In addition to the girls’ original writings—among them poems, flash fictions, and short stories—the anthology contains photographs of each mentor/mentee pair, who are often shown arm in arm. With their names and words in a professionally bound book, the girls experience the feeling of accomplishment that comes with publication. The anthology also serves as a yearbook of sorts, as well as a keepsake. A charitable contribution by Amazon made this year’s anthology possible, and the launch party for it was held at the venerable independent bookstore McNally Jackson, also in SoHo.

Mentors and Mentees

Every Saturday at 11 a.m., Wendy Caster meets Rachel Candelaria at the Barnes & Noble bookstore in Union Square. In the store’s cafeteria, filled with people sipping Starbucks coffee and flipping through magazines, the two sit across from each other and talk about writing. Wendy, 58, is a longtime resident of the East Village and works as a medical editor and freelance theater critic; Rachel, 17, is a junior at Brooklyn’s Williamsburg Preparatory High School who lives in Ridgewood, Queens. Although mentor/mentee weekly meetings need only be an hour long, Wendy and Rachel inevitably spend much of the day together. “Oftentimes we’ll go to Silver Spurs for lunch,” Wendy says, “or McDonald’s if we need Wi-Fi. Last week we went to see the movie The Great Gatsby, which was pretty good. We hang out, we chat, we recommend books to each other.”

The work Wendy and Rachel do together is clearly far less formal than what takes place in a typical classroom with the teacher as the ultimate authority. “I never want to enforce writing, particularly on a teenager,” Wendy says. “That takes away from the playfulness and the joy when someone tells you how to do something. What I do is encourage, support, and compliment. And I don’t do much editing—that’s not the point here. But I do guide Rachel by suggesting that she add more of a plot in order to make her writings more publishable. My goal is to have her complete a formal short story that’s about five pages long.”

Even if Wendy is not teaching in a traditional manner, she is clearly making headway. “With Wendy, I learn to express myself and get my thoughts in order,” Rachel says. “I’m better at doing things than I think—and Wendy helps me focus.”

“You have a lot of ideas,” Wendy interjects, as if speaking respectfully to a peer and not a girl more than 40 years her junior.

Before Rachel was paired with Wendy, she and the other mentees and mentors did a series of “speed datings,” to see if there were any instant sparks of affinity or shared interest; in the end all were matched by the GWN staff based on their personalities, interests, and hobbies. “Both of us have a weird sense of humor—what other people moan and groan about makes us happy,” Rachel explains. But the mentor and mentee are also quite different. Wendy says, “Rachel is a very lyrical writer and I’m, well, unlyrical.”

“You’re straightforward,” Rachel says with confidence, following Wendy’s suggestion to use the most accurate words to express herself.

Mentee Bre’ann Newsome reads from her writing during a workshop.

******

Mentors and mentees often become as close as Wendy and Rachel, and as a result subjects may appear in writings—or surface in the course of conversations—that GWN regards as causes for concern. Among at-risk teens, problems such as depression, anxiety, self-mutilation, bullying, and domestic violence are not uncommon. “Usually,” Nussbaum says, “it’s in the most successful relationships that these issues become apparent,” since the girls open themselves up to women with whom they have bonded. Mental health training sessions are held throughout the year, with mentors taught how to deal with particular issues. In 2010 a GWN Therapy Panel was formed, comprised of a group of mental health professionals who serve and advise the staff. “For girls in need we provide a team that includes a staff member, a parent, a member of our Therapy Panel, and her mentor. We offer group chats, which is basically a loose form of therapy. We also have a trained social worker on our staff,” says Nussbaum.

Mentors and mentees peer critique during a Girls Write Now workshop.

Nussbaum recounts an emotional upheaval experienced by a mentee, Annie (whose name has been changed to protect her anonymity). When Annie’s difficulty came to a head, it was successfully resolved through GWN’s Therapy Panel. Annie, who hailed from Midwood, in Brooklyn, had a passion and a talent for poetry—as well as serious problems involving her parents. “Her language (‘What about the girls who was clawing for motherly?’) was a lyrically skewed vernacular, assured in its rhythms, unsparing in image and tone—accomplished for a poet of any age, and extraordinary for a high school junior,” Nussbaum says. At the end of her first year of high school, Annie—who was already in the Girls Write Now program—ran away from home and went directly to GWN, which helped place her in a shelter for teens. During the weeks she spent there, she visited GWN’s offices and communicated with its staff nearly daily by phone or e-mail. Annie worked with her mentor on a set of poems, and included in their co-written chapbook is work alluding to her jarring experience. Even though mentoring relationships are typically framed by the school year, Annie’s mentor worked with her over the summer and into the next school year. Both her mentor and GWN staff provided extremely important support during that time. Once Annie returned home, GWN helped her obtain the services of a therapist. Through scholarships, she is currently attending college, where she is flourishing.

Another example of how GWN can significantly affect the life of a high school girl is 26-year-old Samantha Carlin, who nine years ago was a mentee. Now a graduate of Barnard College, she has served as a GWN mentor for the past two years. “One of the most important experiences that I remember doing as a mentee,” Carlin recalls, “was taking part in a travel-writing workshop where we had to go somewhere in New York City we’d never been before. I’m Jewish, and had never been inside of a church, and so that was what I did, I went to church, and afterward I went back to the GWN workshop and wrote about it. It was such a quintessential moment of how GWN can open up your mind and heart to new experiences. The GWN theme this year is ‘new worlds,’ which is a perfect one, I think.”

For the past two years, Carlin has mentored 17-year-old Amanda Day McCullough, who attends Hunter College High School and was preparing this past summer for her senior year. Carlin says, “Amanda is varsity captain of the basketball and swim team and is co-president of the women’s issues club. When I met her, I knew right away that I wanted to be her mentor; she has such a go-getter attitude about life. Now she’s at a two-week writing program at Brown University—we worked forever on the essay for that application, and next year we’ll be knee-deep in college applications.” With detectable pride, Carlin says that smaller, elite liberal arts colleges will be Amanda’s focus. Per GWN’s standards, she and Carlin are setting the bar high. “As inspiration, I’ve given her lots of books to read with strong women narrators—novels by Jennifer Egan, Julia Alvarez, Barbara Kingsolver.”

Girls Write Now mentee Paldon Dolma (left) and her mentor, Alice Sheba, attend a college prep workshop.

Back when Carlin was a mentee, her public reading was at the SoHo-based Housing Works bookstore, a smaller and more modest venue than the Scholastic auditorium. She spoke with enthusiasm about the way GWN has grown over the years: “It’s like when your favorite cozy family restaurant expands successfully—the charm doesn’t go away, you just have more capacity and can serve more meals. The heart and the mission remains the same.”

“Serving meals” may be the perfect metaphor for what GWN is doing all around New York, with mentees and mentors seated across from each other at tables in the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, Manhattan, and Staten Island. And while what is being consumed is far less tangible than, say, a plate of fried chicken or a steaming pork bun, by the end of an academic year, these “meals” have become lasting nourishment for the girls’ hearts and minds.

Resources

Girls Write Now; New York, NY ■ Brooklyn Community Foundation; Brooklyn, NY ■ Hive Digital Media Learning Fund in the New York Community Trust; New York, NY ■ Pinkerton Foundation; New York, NY ■ Youth I.N.C.; New York, NY ■ National Endowment for the Arts; Washington, DC ■ New York Women’s Foundation; New York, NY ■ Scholastic Inc.; New York, NY ■ Amazon.com; Seattle, WA ■ McNally Jackson; New York, NY ■ Williamsburg Preparatory High School; Brooklyn, NY ■ Barnard College; New York, NY ■ Hunter College High School; New York, NY.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Guest Voices—

“All the Ends of the Earth Terminate in These United States”: The Need to Accommodate Children of Immigrants in New York City Schools

by Stephan F. Brumberg

Issues of UNCENSORED have typically included Historical Perspective essays and occasional opinion pieces in what we call the Guest Voices column. This issue offers something of a combination of those two features: an essay that looks to the past in expressing a view about contemporary times. Stephan F. Brumberg, professor of education at Brooklyn College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York, is the author of Going to America, Going to School: The Jewish Immigrant Public School Encounter in Turn-of-the-Century New York City and of many education-related book chapters and articles.

New York is a city of immigrants and migrants. From the earliest years of the American republic, New York has been the major entry point for immigrants, many of whom have settled here, and the destination of migrants from all parts of the country. A critical concern for New York’s leaders was and still is how to incorporate these newcomers into the life stream of the city. The welcome has not always been warm and embracing. Open reception and inclusion of newcomers has often given way to animosity and efforts to limit their number if possible or, if not, to segregate them. Whether the city’s leaders and the tenor of the times favored or opposed newcomers, schools have been central to the process of city/newcomer encounters and to the fractious process of accommodating and integrating migrants and immigrants.

In 1800 New York City was a large and rapidly growing town of some 60,000 inhabitants. Within a decade its population had increased by 60 percent, due largely to immigration. The established leaders of the city, concerned for political, social, and economic stability, were disturbed by the growing number of poor residents whose children were for the most part unschooled. At that period there was no free “public” education; all schooling was private and for-pay, with the exception of a meager number of charity schools. Of especial concern to New York’s establishment was the moral corruption that infected the life of the city, and the poor who, they believed, were the carriers of such infections. Men such as De Witt Clinton, John Murray, and Thomas Eddy established a private philanthropy, the Free School Society (later the Public School Society), in 1805 to address impoverished children’s need for basic education, especially moral instruction, and the city’s need for social control and stability. The three men sought to employ their schools as a means of shaping and informing the moral lives of these impoverished children and of severing the children from the perceived dissoluteness of their parents’ culture. These men acted out of benevolence toward the children of the poor and out of a desire to render a service for the public good.

In 1842 the state legislature compelled New York City to create a free public-education system. At this time the city’s residents numbered more than 300,000, and the proportion of immigrants, primarily Irish and German, was approaching half of the population. The need to address the rapid influx of “foreigners” was felt with particular acuteness by the evangelical Christians, who saw themselves severely challenged by the large percentage of Catholics among the immigrants and by what they felt to be the newcomers’ assault on the moral life of the city. They argued that the recently created public-school system had to carry the light of Christian faith and morality to the benighted, for their own sake and for the city’s survival. Many religious conservatives believed that New York and other cities were cesspools of evil and vice that grew in proportion to the cities’ immigrant populations. In the view of the Protestant religious establishment of the city, the schools could not be neutral in this situation. If the public schools did not provide proper religious instruction and did not shape the moral character of their students according to “Bible truth,” they would become party to the evil and breeders of vice and crime.

Moral instruction was central to the mission of the schools, including “public schools.” Benjamin Peers, an early-nineteenth-century American educator and Protestant minister, succinctly sets forth the argument for moral instruction and expresses the need for America’s schools to embrace the Bible. Writing as systems of common schools were beginning to appear, he argued that society “has more occasion for the moral, than the intellectual education of its members. This is uniformly and practically acknowledged by our legislators, since law is generally addressed to the moral faculties of man.” Peers maintained that public morals were crucial to the success of the American republic, but that it could not be assumed that public virtue would be included in the spread of popular knowledge. Learning to read was not equated with acquiring virtue. “The popular virtue which is essential under a government like ours, can be produced only by means of the Christian Religion engrafted upon our system of popular education,” which required that the Bible be “enthroned” in the schools. Note that Peers and the evangelicals, who pressed for attention to moral instruction, had no inhibitions when it came to imposing a religious position that might have been anathema to many parents of the children attending the city’s public schools.

The central role of the public schools in the acculturation and integration of immigrants in mid-nineteenth-century America can be seen in arguments that a Baptist minister from Newark, New Jersey, Henry C. Fish, directed against Catholics seeking a share of public-education funds to finance their own parochial schools. Fish maintained that the American common school served a critical integrative function. Sectarian schools, wrote Fish,

tend to perpetuate among us national distinctions, in feeling, and sentiment, and action. We are made up of strange and as yet, unaffiliated elements. All the ends of the earth terminate in these United States. [italics Fish’s; boldface added] … Now what we need is some powerful and rapid process of amalgamation … Indeed, it would seem obvious that this is almost a condition of success in the great experiment of American republicanism.

Fish argued that the common school, more than any other institution in society, was capable of synthesizing the disparate peoples who populated America:

It is framed for the masses. Jews, Greeks, Pagans, Europeans, Africans, Asiatics and Americans, all here meet; and meet in childhood and youth; just when in the formation period. Then if ever, and by these schools, if by any means, are they trained for a common destiny. Here they become Americanized [boldface added]. Here the future actors on the state are brought together, and made acquainted with each other. They see each other face to face, and grow up side by side. Thus are prejudices and bitter animosities worn away, or softened down, so as not to produce irritation. Thus are the children of all other nations run into the new mould [sic] of our institutions, with our own children, and thus is there formed one consolidated body politic.

Fish concluded that if the Catholic Church chose to separate its children from the American public school, then it should not ask for public funds to do so.

The great wave of immigration at the turn of the twentieth century helped to raise New York City’s population to more than 3.4 million. The city’s leaders felt that immigrant parents were unable to properly raise and educate their children and continued to believe that immigrant and other impoverished children suffered from moral and social degeneracy. These two perceived failings served as a call to action and as the justification for the broadened functions and scope of elementary education in New York City. In seeking to reshape immigrant youth, school leaders ran the risk of creating a rift between immigrant parents and their children. While they gave lip service to the biblical maxim of honoring thy mother and father, the schools themselves, through their institutional, cultural, and instructional programs, only widened this gap.

In our own day, the schools of New York City enroll large numbers of immigrant and migrant children. Over a third of New Yorkers are foreign-born, and their children represent another 17 percent of the population. Well over half of our public-school students are either immigrants or children of immigrants.

Yet our schools have not adapted themselves to this reality. Throughout the city’s educational history, the child has been asked to adapt to the school and not the school to adapt its educational program to the child. The official bureaucracy, whether called a school board or the Department of Education, imposes its will upon all, regardless of the wishes of those it purports to serve—the children and their parents. Let us look at one central example of such imposition that seems to signal an obliviousness to the particular needs and wishes of students: the Common Core State Standards.

The Common Core English-language arts and mathematics standards, now adopted by 45 states and the District of Columbia, are at the center of efforts to reform our schools today. They set ambitious learning standards with a focus on students’ abilities to analyze, understand concepts, and acquire skills needed for college and beyond. States and school districts are racing to construct curricula consistent with these goals and, not coincidentally, prepare students for the examinations which will measure their learning (and the schools’ effectiveness). The curricula comprise a common core of prescribed learning for all students: children from well-established families and newcomers, students of affluence and of poverty, students who enter school speaking English and those who do not.

In many respects we are back to the beginning of the nineteenth century: newcomers and outsiders, be they immigrants or migrants, English speakers or not, from families with adequate incomes or those living in poverty, comfortable with American culture or not—all are required to achieve similar learning outcomes and in the same time frame. Little is built into contemporary reforms to address the needs of newcomers— issues arising from poverty or from differences related to language or culture. We no longer speak in terms of “Americanization” nor make an explicit effort to transform the children of immigrants into upright, productive, English-speaking, fully acculturated Americans. However, implicit in the goals and timetables of the Common Core is the goal of such “Americanization.” Yet little if any instructional effort is directed to the realization of that goal among newcomers. Bilingual and bicultural education is offered in some cities and schools, but how are these programs to be integrated into the Common Core? If a school is to be judged on Common Core–related student performance, how will bilingual/bicultural and dual-language programs be accommodated and supported?

Reflecting on contemporary reform, Paul Reville, former secretary of education for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, argues “that schools alone, conceived in our current early-20thcentury model, are too weak an intervention, if our goal is to get all students to high levels of achievement … today’s schools have not proven powerful enough by themselves to compensate for the disadvantages associated with poverty.”

Reville’s analysis helps us to connect contemporary problems confronting reformers with the experiences of educational reformers in the past. “Our ‘modern’ school system,” he writes, “is a fortified version of an educational model designed [in the early twentieth century] to batch-process large numbers of immigrants and migrants with a rapid-turnaround model set to socialize and prepare them for useful roles in a burgeoning low-skill, low-knowledge, manufacturing economy.” The old system, as heavy-handed and as unsavory in some ways as it was, worked for many under the social and economic conditions of a century ago. Those conditions are not present today.

In any conversation regarding a “new” model of education for America, we must take into account the diverse nature of the population we serve. All the ends of the earth still seek their terminus in America. We must find ways to open a dialogue with newcomer parents, to understand their needs and wishes as we try to communicate to them our educational goals for their children. We must be alert to the dangers of insinuating the schools between parent and child. Those in authority must temper the impulse toward imposition (“We know what is best for you”) with the rights of parent and child to their own agency, i.e., to make their own choices and work toward their own ends. We need to work collaboratively with parents to underline and reinforce the shared responsibility of parent and school for each child’s education. We do not want to exacerbate the gap that is often the consequence of parent and child coming of age in two distinct cultures.

We must keep in mind that over half of the children entering public schools in New York City are immigrants or children of immigrants, the majority of whom do not speak “standard” English as their first language, and that many do not speak English at all. Yet we still plunge these children into English-language reading instruction before they know the language they are asked to read; we teach them phonics to help them to decode English words they may not know, even when a large number of them will not yet be able to aurally comprehend the phonemes of English.

We need to design an instructional program that acknowledges the child’s first language (whether or not we seek to sustain his/her fluency in that language), and which explicitly teaches the English language through songs, poems, plays, word games, and so on before we introduce the child to English reading. Oral/aural fluency in English needs to precede reading. We need to devise a means of teaching American culture without denigrating the culture a child brings with him/her to school. We need to find a way to bring the newcomer inside American society, and to create schools that can provide the best means of doing so. We must learn to rejoice that all the ends of the earth terminate in these United States, and especially in the City of Greater New York.

Resources

Kaestle. Carl F. The Evolution of an Urban School System: New York City, 1750–1850. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1973. ■ Kaestle, Carl F. Pillars of the Republic. New York: Hill & Wang, 1983. ■ Peers, Benjamin. American Education: or Strictures on the Nature, Necessity, and Practicability of a System of National Education, Suited to the United States. Introductory letter by Francis L. Hawks, D.D. New York: John S. Taylor (1838): 35. ■ Fish, Henry C. [pastor of the First Baptist Church, Newark, New Jersey]. “Romanism and the Common Schools. A Discourse, Delivered on Thanksgiving Day,” November 24, 1853. New York: Holman, Gray & Co., Printers (1853): 17–18. ■ Kasinitz, Philip, John Mollenkopf, Mary Waters, and Jennifer Holdaway, Inheriting the City: The Children of Immigrants Come of Age. Cambridge, MA and New York: Harvard University Press and Russell Sage Foundation, 2008. ■ Reville, Paul. “Seize the Moment to Design Schools That Close Gaps.” Education Week (June 6, 2013): 36.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.