Publisher’s Note

Dear Reader,

Welcome to the Fall 2015 issue of UNCENSORED where we share an in-depth examination of creative, innovative approaches that link research to policy and policy to practice. This issue explores the technology gap between low-income students and their peers in “The Digital Divide,” and takes a look at how some community agencies are narrowing that gap by improving low-income students’ access to technology and computer science education.

“Changing Lives with a Knock on the Door” describes the home visiting model of support for expectant and new parents. This article contains stories of lives changed by personal, long-term relationships with nurses and other trained professionals who spend time with parents to make sure they have all the help they need to begin raising healthy families. In “Middle Class by Middle Age,” you will learn how City of Refuge, a nonprofit in Atlanta, Georgia, is addressing the booming suburban poverty rate with innovation that includes culinary and automotive social enterprises.

While access to fresh produce is increasing in low-income communities, curious consumers are often not certain how to incorporate new foods into their family’s daily meals. “Eating Well Should be a SNAP” serves up resources that explain how to prepare nutritious, inexpensive meals.

Our National Perspective features part of a new state ranking system developed by ICPH in our 2015 American Almanac of Family Homelessness. The state education rankings measure how well states are identifying and providing services to homeless children. We invite you to take a peek to see where your state ranks.

As always, we welcome your comments and ideas for future issues at info@ICPHusa.org.

Sincerely,

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, Publisher

President and CEO, Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The Digital Divide:

Bringing Low-Income Students to the Cutting Edge of Technology

by Katie Linek

On a beautiful Saturday morning during the summer, laughter and excitement echoed through the computer room at The Prospect, a Community Residential Resource Center (CRRC)* in the South Bronx, operated by the nonprofit organization Homes for the Homeless. This Saturday is the final day of Coding Made Easy, a program where volunteers from the organization New York Cares meet with children to help them learn the basics of coding. A handful of children click away at their computers as the volunteers answer questions and guide the children through a series of games that teach them the basics. As the children have fun, few of them realize just how important the skills they are gaining are for their future.

* CRRCs combine the basic services of a traditional homeless shelter with programs for families living in both the shelter and the surrounding neighborhood.

Modern technology is an integral part our daily lives. It has changed the way people live, work, learn, and play and is crucial for the progression of society. Unfortunately, this rapidly evolving world may be leaving lowincome students behind.

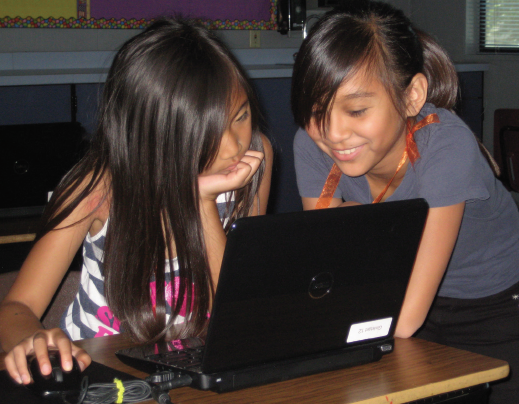

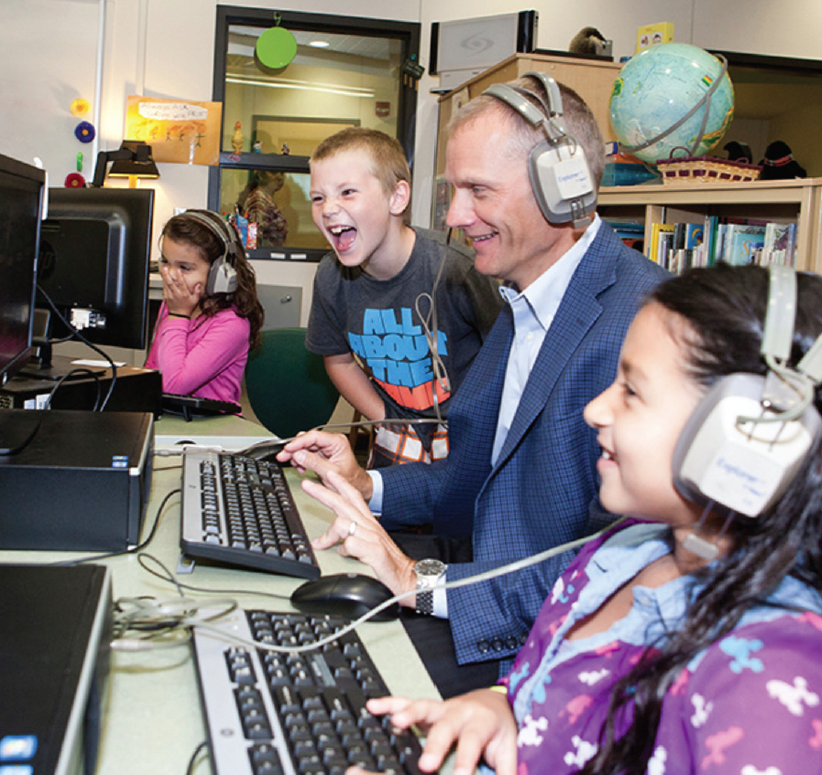

Low-income homes and schools are less likely to have the technology infrastructure needed to be effective in helping children learn. Digital Promise is a national organization working to improve the opportunity for all Americans to learn through technology and research. Photo courtesy of Digital Promise.

Technology has been hailed as an equalizer of educational opportunity. Access to the Internet can change an underprivileged child’s life by providing access to the same tools and resources as other students. That is, if his or her family can afford it. Access to technology costs money, putting a barrier between low-income students and success by creating a digital learning gap.

“The digital learning gap has three key factors,” explains Jason Tomassini from Digital Promise, a national organization that works to improve the opportunity for all Americans to learn through technology and research. “First is access. Studies show that low-income households are less likely to have Internet access and technology at home, and low-income schools are less likely to have the types of Internet speeds and infrastructure that allow them to do truly interesting and effective teaching.”

Low-income students often do not have the same access to technology as their more affluent peers—both at home and at school. The 2012 Pew Report “Digital Differences” found that in households with an income of $30,000 or less, only 62 percent of people used the Internet versus 90 percent of people in households making $50,000–74,999. According to the Census Bureau, one in four U.S. households do not have Internet access.

The Internet brings a world of information to the fingertips of low-income students, engaging and empowering them. That is why organizations such as EveryoneOn are working to change this limited access. EveryoneOn is a national nonprofit working to eliminate the digital divide by making high-speed, low-cost Internet service, computers, and free digital literacy courses accessible to all unconnected Americans. Through partnerships with local Internet service providers, they are able to offer free or low-cost Internet service in 48 states and the District of Columbia. Their Connect2Compete program provides Internet and devices to students and families that qualify for the National School Lunch Program (often used as an indicator of lowincome status).

At school, the digital divide continues. Many low-income schools do not have technology in the classrooms and some evidence suggests that schools in low-income neighborhoods that do have technology tend to use computers for drill and practice sessions rather than for creative or innovative projects. In a Pew survey of teachers, teachers of low-income students tended to report more obstacles to using educational technology effectively than their peers in more affluent schools. Among teachers in the highest income areas, 70 percent said their school gave them good support for incorporating technology into their teaching. Among teachers in the lowest income areas, that number was just 50 percent.

Many schools are now offsetting this lack of access with one-to one laptop initiatives, which provide each student with their own laptop to use both in and out of school. Roanoke County Public Schools in Virginia was an early adopter of one-to-one digital learning, launching their laptop initiative in 2002. There, all high school students are provided with laptops, allowing teachers to integrate interactive lessons and personalize learning for each student. An important part of this program is empowering teachers to use the laptops in creative and innovative ways, with the support of an instructional technology resource teacher in every high school. Because of this innovative approach, Roanoke County Public School District is part of Digital Promise’s League of Innovative Schools, an elite network of superintendents and district leaders leveraging technology to improve student outcomes. A national research project on one-to-one computing found that schools that implemented these initiatives saw increased engagement in school work, improved academic performance, decreased dropout rates, and increased graduation rates. Another benefit of one-to-one laptop initiatives is that students may be the first in their families to have a laptop, and inevitably teach family members digital literacy skills.

While access to adequate equipment and reliable highspeed connections is a concern, improving the way that technology is employed in learning is even more important. “Another key factor of the digital learning gap is participation,” says Tomassini. “Not only do you need the access, but students need to be supported and to know the best ways to participate in technology. Are students digitally responsible? Do they understand that there is a difference between using these tools for learning and using these tools for entertainment?”

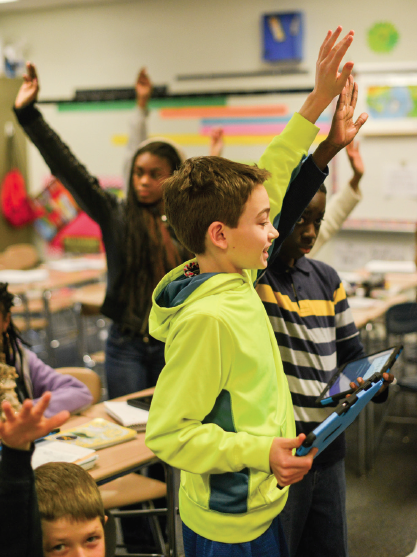

There are three key factors to the digital learning gap: access, participation, and whether students are using technology powerfully. Photo courtesy of Digital Promise.

When given access to technology, affluent children and low-income children use it differently. They select different programs and features, engage in different activities, and come away with different kinds of knowledge and experience. This may be due in part to the influence adults have on children’s computer use. In one observational study, affluent children accessing the Internet were frequently accompanied by parents who asked and answered questions, made suggestions, and directed them away from games and toward educational opportunities. A majority of low-income children however, were observed accessing the Internet on their own. This resulted in affluent children reading more words, accessing more educational information, and feeling less frustrated when learning to use technology.

“The final factor is whether or not they are using the tools powerfully,” says Tomassini. “Are teachers able to try completely new things and get results that would not otherwise be possible because they now have access to technology? That is where we want to make sure that low-income students and classrooms are getting to.”

Tomassini continues, “We want them to have the same access to really interesting projects. We want them to be inspired—to be creative and creators of content, not just consumers of content. It is still necessary, even after you have provided the access, to make sure that we are not just putting devices in classrooms and calling it a day; that we are actually using it to really enhance learning for students that might not have a lot of really strong learning opportunities to begin with.”

For Hire: One Million Tech Workers

Digital literacy is a commodity in today’s workforce; basic computer skills are now a necessity in most jobs, as every industry grows more and more reliant on technology. The digital learning gap not only puts low-income students at a disadvantage in the workforce later on in life, it influences the careers that they choose. Low-income students are severely underrepresented in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) careers.

“Very often low-income students have all kinds of things stacked against them,” says Claus von Zastrow, COO and director of research for Change the Equation, a non-profit initiative to improve STEM education in the United States. “On the one hand, they are less likely to have family members or direct role models who are STEM professionals. Very often they are in schools that are not as well equipped with STEM resources, they are much less likely to have teachers experienced in STEM, and the list goes on and on.”

Girlstart participants consistently out-perform their peers on state-mandated math and science tests, and they enroll in advanced math and science courses and STEM electives at a significantly higher rate than their non-enrolled peers. Photo courtesy of Girlstart.

That is why The Saratoga, a CRRC operated by Homes for the Homeless in Jamaica, Queens, invited the Great Neck South High School Robotics Team to come visit students in The Saratoga’s after-school program. Along with working as a team to research, design, and construct robots, the robotics team brings their enthusiasm for science and technology to younger students in the community. While at The Saratoga, the team spoke to the kids about robotics, demonstrated a robot they built, and then gave students a chance to control the robot themselves. Afterward, students had the opportunity to put what they had learned into action by building robots of their own.

“It is great when outside organizations come in and show the kids something they may not ever get to see,” says Michael Fahy, administrator at The Saratoga. “Then we are able to follow it up on a smaller scale. It means a lot for a child to learn something here and then go to the outside community and say, ‘I built a robot!’”

Another program, Austin, Texas-based Girlstart, works to increase girls’ interest and engagement in STEM through innovative programs. In the 2012–13 school year, 68 percent of their participants were economically disadvantaged. Their after-school program reaches more than 1,300 4th– 6th grade girls in highneed schools in Central Texas with free STEM education programs each week for two semesters. This after-school program encourages young women to believe in themselves and to pursue paths to higher education and greater career opportunities in STEM. Research shows that participants in Girlstart’s after-school program consistently out-perform their peers on state-mandated math and science tests, and they enroll in advanced math and science courses and STEM electives at a significantly higher rate than their non-participant peers.

Girlstart meets Change the Equation’s rigorous principles, gaining the program a spot in Change the Equation’s searchable STEMworks database of in-school and out-of-school STEM learning programs that embody the best research on what works in STEM learning. Programs in STEMworks must demonstrate success in areas such as capacity to meet a critical need, sustainability, scalability, partnerships, and rigorous evaluation. In addition, programs must offer challenging STEM content, incorporate hands-on STEM practices, inspire interest in STEM, and address the needs of youth, such as girls and students of color, who are less likely to pursue STEM fields.

“We want them to have the same access to really interesting projects,” says Jason Tomassini of Digital Promise. “We want them to be inspired—to be creative and creators of content, not just consumers of content.” Photo courtesy of Digital Promise.

The best opportunities for low-income students lay in the STEM field. The Department of Commerce found that STEM workers earn 26 percent more in wages than comparable workers in non-STEM occupations. Not only that, but STEM is a rapidly growing field. A 2015 report from Change the Equation projects that between 2014 and 2024, the number of STEM jobs will grow 17 percent, as compared to 12 percent for non-STEM jobs. Among these STEM occupations, computer science is the only STEM field where there are more jobs than there are students coming into the field. In fact, computer science drives 60 percent of new jobs in STEM.

Moreover, the U.S. needs to find roughly one million more tech workers within the next five years, spurring an even greater drive to close the digital learning gap and inspire low-income students to join the field. Currently, high-income, white males dominate the computer science field, however, dozens of schools, organizations, and politicians are joining the effort to change that.

Computer Science: Coming to a School Near You

Some suggest that low-income students are just not interested in computer science, but most students have not had any exposure to it. Only 10 percent of U.S. high schools offer it as a course and only nine states allow computer science to fill a math or science requirement—until now. In New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio recently announced that all of the city’s public schools would be required to offer computer science to all students. Chicago pledged to make computer science a graduation requirement by 2018 and to offer computer science to at least a quarter of elementary school children by then. In San Francisco, computer science is mandatory through the eighth grade. Various other schools in cities across the country have recognized the importance of computer science and have implemented their own programs.

In October 2015, The STEM Education Act was signed into law by the president, officially including computer science as a STEM subject and taking a major step toward including computer science in the curriculum of all U.S. schools.

Everyone Can Have a Superpower

Many organizations are reaching out to low-income children across the country and providing them an opportunity to change their lives. Programs like #YesWeCode aims to teach 100,000 low-income kids how to write code. Another program, Hack the Hood, introduces low-income youth of color to careers in tech by hiring and training them to build websites for small businesses in their communities. Google’s free program, CS First, increases student access to computer science education through after-school, in-school, and summer programs.

Code.org, a non-profit dedicated to expanding access to computer science, likens the skill to a superpower in their short film Code Stars. In it, Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook, explains, “One of the biggest misconceptions about computer science and programming overall is that you have to learn this big body of information before you can do anything.”

The Saratoga in Jamaica, Queens, invited the Great Neck South High School Robotics Team to visit their afterschool program. Along with working as a team to research, design, and construct robots, the robotics team brings their enthusiasm for science and technology to younger students in the community.

That is what each of these programs has in common—their effort to make computer science less intimidating and more approachable to those who previously thought it was out of their reach.

“It took me some time to realize that creating things with your hands, or creating code, creating programs, is just a different way to express creativity,” says Elena Silenok, creator of Clothia.com, who was also featured in the short film.

At The Prospect in New York City, the children are using a curriculum from Code.org. Each child takes part in one of three courses based on their age and the difficulty level of the course.

“Code.org is a program online that basically helps teach kids the fundamentals of coding,” explains Melissa Pallay, one of the New York Cares volunteers. “Essentially they complete different questions and programs and they go through different levels and exercises to teach them the fundamentals of programming, like loops and functions.”

Similarly, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) developed a new computer language to help facilitate that muchneeded user-friendliness. Scratch is a visual drag-and-drop language that lets students program their own interactive stories, games, and animations. It is provided free of charge and is used by in-school, after-school, and shelter programs across the country to bring computer science to low-income students.

“Using a set of about 100 commands that can be snapped together visually, you can create just about anything and learn the fundamentals of more advanced languages,” said one teen about Scratch. In Code Stars, an elementary school teacher explains, “What I saw my students take away from using Scratch and programming in our classroom is that they are willing to push through problems. It really builds critical thinking. It builds problem solving. It is something that they can then apply to math in the classroom or reading skills.”

From the White House to Your House

Even the White House has focused its efforts on this computer science push, recognizing that technology is an essential ingredient of economic growth and job creation.

“We should be making it easier and faster to turn new ideas into new jobs and new businesses,” said President Obama in 2011. “And we should knock down any barriers that stand in the way. Because if we are going to create jobs now and in the future, we are going to have to out-build and out-educate and out-innovate every other country on Earth.”

Nearly 40 homeless and at-risk children participated in Coding Made Easy at The Prospect. As they receive their certificates of completion, they all agree that they had fun and that coding was not so hard after all.

Bringing more diversity into the tech field can only serve to expand the talent pool and keep the U.S. on the cutting edge of innovation. Steve Wozniak, co-founder of Apple, recognized this fact when supporting the organization #YesWeCode. “Diversity brings so much more to the table, and by focusing outside of the usual and rewarding all sorts of people in tech, we can only make it better. #YesWeCode is doing exactly that.”

In 2013, President Obama released a video kicking off the Hour of Code campaign, an online event organized by Code.org to promote Computer Science Education Week. The Hour of Code is a one-hour introduction to computer science, designed to demystify code and show that anyone can learn the basics. “Learning these skills is not just important for your future, it is important for our country’s future,” Obama said in the YouTube video. “If we want America to stay on the cutting edge, we need young Americans like you to master the tools and technology that will change the way we do just about everything.”

He continues, “Do not just buy a new video game—make one. Do not just download the latest app— help design it. Do not just play on your phone—program it.”

In 2014, President Obama took it a step further when he became the first president to write a line of code. “Part of what we are realizing is that we are starting too late when it comes to making sure that our young people are familiar with not just how to play a video game, but how to create a video game,” he said at the Hour of Code event. “One of the great things about America is that we invent and make stuff, not just use it.”

Learning How to Think

Even if a career in computer science is not of interest, every American should gain a basic understanding of the subject. A general computer science curriculum largely consists of critical thinking, problem solving, and logic—skills that students will need in order to compete for the best jobs, whether or not they go into the tech field.

According to a 2015 report from Change the Equation, simply being able to use a smartphone or Facebook is not enough. To be successful in a global economy, children must become fluent in the technologies that are revolutionizing our lives and our work.

“Do not just buy a new video game—make one. Do not just download the latest app—help design it. Do not just play on your phone—program it.”

—President Obama

“Although only 10 percent of schools teach computer science classes, even one hour of exposure can be enough to change a student’s life, as it did mine,” said Code.org founder Hadi Partovi. “In the 21st century, this is not just a course you study to get a job in software—it is important to learn even if you want to be a nurse, a journalist, an accountant, a lawyer, or even a president.”

There are numerous benefits to learning computer programming. It teaches problem solving and algorithmic thinking, it stimulates design and creativity, and it strengthens math and reading skills. Beyond that, learning how to code can increase confidence when using computers, instill courage to try new things, build perseverance when tackling difficult problems, and provide a sense of belonging in a field that plays an essential role in the 21st century.

In addition, computer programming provides children with a new tool to express themselves in ways they were once unable to. It is now part of general literacy; it is necessary to understand and communicate with the different technologies that run the world.

“Programming makes a really big difference in how you view the world and how you solve problems,” says Pallay, the New York Cares volunteer at The Prospect. “I think kids and really anyone of any age can benefit from learning how to program. Getting them to do it at such a young age really sets them up for something great.”

A national research project on one-to-one computing found that schools that implemented these initiatives saw increased engagement in school work, improved academic performance, decreased dropout rates, and increased graduation rates. Photo courtesy of Digital Promise.

Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook, a company that has revolutionized the way people interact online, had a private tutor as a child to help encourage his love of computers and went on to attend a prestigious school. Not every child has those same advantages. Imagine all of the children who could make a difference in the world if someone was there to encourage their love of computers.

The world is rapidly changing. If we want children to be successful when they leave school, we have to invest in preparing them for that change.

Nearly 40 homeless and at-risk children participated in Coding Made Easy at The Prospect, writing over 13,500 lines of code, proving that anyone can learn to code and have fun doing it.

Resources

New York Cares https://www.newyorkcares.org New York, NY ■ Digital Promise http://www.digitalpromise.org Washington, DC ■ Pew Research Center; Washington, DC ■ U.S. Census Bureau http://www.census.gov Washington, DC ■ Roanoke County Public Schools; Roanoke, VA ■ Change the Equation http://www.changetheequation.org Washington, DC ■ Great Neck South High School Robotics Team http://www.gnsrobotics.com Great Neck, NY ■ Girlstart http://www.girlstart.org Austin, TX ■ #YesWeCode http://www.yeswecode.org Oakland, CA ■ Hack the Hood http://www.hackthehood.org Oakland, CA ■ CS First; Mountain View, CA ■ Code.org https://code.org Seattle, WA ■ Massachusetts Institute of Technology Scratch; Cambridge, MA.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Changing Lives with a Knock on the Door:

Home Visiting Programs for Struggling Families

by Lauren Blundin

Jalisa Terry was pregnant, broke, and alone. Her boyfriend kicked her out of his apartment and threw her clothes out of the window when he found out she was pregnant. Terry sat in a restaurant next to her pillowcase stuffed with clothing and wondered what to do next. Then she remembered she had a phone number for Susan Timmons, the supervisor for the Women’s Health Initiative (WHIN) in West Palm Beach. Timmons had met Terry the year before when she miscarried a previous pregnancy. Terry made the call, and in no time Susan Timmons was sitting in the restaurant with her. After speaking for a bit, Timmons made a series of phone calls to arrange for shelter and other short-term assistance for Terry. She also enrolled Terry in WHIN’s nurse home visiting program.

The Healthy Mothers Healthy Babies home visiting program improves birth outcomes by supporting pregnant women and teens in Palm Beach County, Florida.

The WHIN program is specifically targeted toward black mothers at risk of poor birth outcomes. Program participants are paired with a nurse who visits their home to support them during pregnancy and after childbirth, through the child’s first year. Nurses teach the mothers about developmental stages, nutrition, and more. The intensive support program is based on a national evidence-based model, and it changes lives. “If I did not have the WHIN program, who can say where I would have ended up,” Terry says. “I would probably still be in a bad relationship, being abused. Mya (her daughter) may or may not be here. I cannot say I would have been able to give Mya the quality care, love, and attention that she needs and deserves if I did not have Miss Susan, the WHIN program, or the Children’s Services Council with all the programs they have in place.” Today Terry is a confident mother to Mya, who is healthy and happy, and works as a phlebotomist while studying to become a medical assistant. Her longer-term goal is to become an obstetrician.

A Helping Hand for Pregnant Women and Mothers of Young Children

Across the country, government agencies and nonprofits are acting on the evidence that home visiting programs can have a significant, positive effect on families. Home visiting programs like WHIN are voluntary, locally-managed programs that support the physical and emotional development of children (prenatally through age five) and also support the overall family. In addition to monitoring a woman’s pregnancy, a home visitor might provide information on child development, parenting strategies, counseling resources, continuing education, employment, and quality child care. The home visitor builds a relationship with the family and works in partnership with parents to improve maternal and child health, prevent child abuse and neglect, encourage positive parenting, and promote child development and school readiness.

A home visitor might, for example, help an expectant mother access prenatal care and help her reduce her use of tobacco, alcohol, or illegal drugs. After the birth of the child, a home visitor might then support the new mother in breastfeeding and learning to care for a newborn, educating her on child development milestones, and providing information on positive parenting strategies. Home visiting programs also facilitate screenings and referrals to address postpartum depression, substance abuse, family violence, and developmental delays.

The Nurse-Family Partnership model of home visiting targets first-time mothers and their children. Nurses visit pregnant women in their homes regularly throughout their pregnancy and afterwards, helping new mothers bond to their baby and learn about infant and child development.

All of this support is invaluable to program participants, many of whom have not had strong parenting models of their own to lead them. With the knowledge provided by the home visitor, parents are given the tools they need to confidently assume the role of their child’s first teacher. “Through my home visitor’s help, I can help my baby grow better, or stimulate her mind the right way, or know what she is supposed to be doing [at a particular stage],” says an Illinois mother who has benefited from a Healthy Families America home visiting program. “Because otherwise I would just be like, ‘Okay, what do you want?’ I would not know what parts of her brain are developing at what time. And I just might be able to encourage her growth so she becomes the best little girl that she can be.”

Federal funds for home visiting programs are intended to support communities with poor outcomes for children, such as those with high rates of fetal and infant mortality, poverty, and crime. National data from 2014 on home visiting shows that these programs are reaching children and families who are at risk of poor outcomes: 79 percent of participating families had household incomes at or below federal poverty guidelines (an annual income of less than $23,850 for a family of four), and of newly enrolled households, 27 percent included pregnant teens, 20 percent reported a history of child abuse and maltreatment, and 12 percent reported substance abuse.

Expanding Home Visiting Programs Nationwide

In 2010 Congress created and invested $1.5 billion in the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program (MIECHV). (Home visiting programs existed before then, and were shown by research to improve child outcomes, but the 2010 federal program represented the first time there was a nationwide expansion of home visiting programs.) The Health Resources and Services Administration administers the MIECHV program in partnership with the Administration for Children and Families. As a result of the 2010 investment in expansion, home visiting programs now exist in all 50 states. In 2014, the programs served approximately 115,500 parents and children, which is triple the number served in 2012.

MIECHV provides funding and technical assistance to states, but the individual programs are locally managed. States choose which home visiting model to use and support local agencies in delivering the home visiting services.

Home visiting program models vary somewhat (e.g., some serve pregnant women while others support families after childbirth), but there are commonalities. In all models, visitors are trained professionals who meet regularly with families, build positive relationships with them, evaluate each family’s needs, and provide services based on those needs.

Home Visiting Models That Work

By law, states must spend the majority of federal home visiting funds on evidence-based models of home visiting programs. But which programs can be considered evidence-based? To address the issue, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) arranged a thorough review of home visiting research to identify program models that meet its criteria for a research-based home visiting model. The review—called the Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness (HomVEE) review—examined the impact home visiting models had among measures in eight domains: child health; maternal health; child development and school readiness; reductions in child maltreatment; reductions in juvenile delinquency, family violence, and crime; positive parenting practices; family economic self-sufficiency; and linkages and referrals.

As of February 2015, 17 home visiting models met the criteria established by the DHHS for an evidence-based model. A HomVEE report specifically recognized two of those models, Healthy Families America and Nurse-Family Partnership, for their positive impact on measures in multiple domains. Healthy Families America visits begin prenatally and are hour-long and weekly until children are six months old, when visits may lessen in frequency but continue until children are three to five years old. The Nurse-Family Partnership program targets first-time mothers and their children. Visits begin prenatally and end when the child turns two years old.

Needs vary among families, leading states to use a combination of home visiting models to ensure families have access to a model with an appropriate level of intensity for their needs. Baltimore, Maryland and Palm Beach County, Florida are just two examples where government agencies and nonprofits have joined forces to provide appropriate home visiting programs for mothers and families.

Home Visiting in Action: B’more for Healthy Babies

In 2009, Baltimore had the fourth highest infant mortality rate in the nation. City policymakers conducted a needs assessment and literature review to identify problems and potential solutions. They identified home visiting as a critical piece of an overall early childhood system of care. Although home visiting existed in the city, the programs were disparate, did not share strategies, and did not provide service to all areas of the city. Baltimore policymakers designed an aligned system of care that includes home visiting programs based on the Nurse-Family Partnership and Healthy Families America models. Key features of the program are a central system to identify mothers and a single point of entry into the home visiting program.

“B’More for Healthy Babies is Baltimore’s initiative to reduce infant mortality,” says Laura Latta, director of early childhood initiatives for B’more for Healthy Babies and Family League of Baltimore. “The initiative is led out of the Baltimore City Health Department with two main implementing partners: The Family League of Baltimore and Healthcare Access Maryland.” Because the need for support outweighs the city’s capacity to provide it, B’More for Healthy Babies uses a triage approach.

Baltimore, Maryland and Palm Beach County, Florida are just two examples where government agencies and nonprofits have joined forces to provide appropriate home visiting programs for mothers and families.

“Basically there are about 8,000–9,000 births annually,” says Latta, “and of those births about 5,000–6000 are Medicaid eligible. But there are only 1,500–2,100 home visiting slots. So, regardless, we are not able to provide intensive one-on-one services to everyone. We want to make sure the women who need them the most are getting connected.”

When women are screened for the home visiting program by Healthcare Access Maryland (the intake partner for B’More for Healthy Babies), the intake worker applies a “vulnerability index.” The index ensures women are matched to home visiting services based on their risk profiles for poor birth outcomes, rather than by zip code or census data, which was previously the case. This way, women at the most risk will receive the most help as soon as possible.

“What we had in Baltimore before B’More for Healthy Babies was nine or ten different home visiting programs operating on their own, with differing models and curriculum, and only one was evidence-based,” says Latta. “We brought the funding streams and agencies together and now we have a citywide system that includes home visiting.” The city’s efforts have paid off. In 2014 Baltimore had an all-time low for the number of infant deaths related to unsafe sleep (13 down from 27 in 2009). Sleep is considered safe when the baby is alone, on its back, and in a crib clear of toys, pillows, and blankets. Also, between 2009 and 2012, there was a 24 percent decrease in infant mortality and a 37 percent decrease in the racial disparities for infant mortality.

Home Visiting in Action: Palm Beach County, Florida

The Children’s Services Council of Palm Beach County is a special taxing district created by voters in 1986 to tax and fund initiatives to support children and families. The Council funds different services and programs in the community, training for providers and professionals, and research and evaluation of programs.

The system of early childhood care screens the needs of the community and families and then refers families to appropriate programs. “We have a robust data system,” says Lisa Williams-Taylor, CEO of Children’s Services Council of Palm Beach County. “We can see the number of births, and of those how many were screened, how many were at risk, how many declined services, and how many accepted services. We can use this data to see where we can we do a better job of explaining services, and it helps us figure out how to meet the needs of the families.”

The home visitor builds a relationship with the family and works in partnership with parents to improve maternal and child health, prevent child abuse and neglect, encourage positive parenting, and promote child development and school readiness.

As in Baltimore, the Palm Beach County home visiting programs include the Nurse-Family Partnership and Healthy Families America models. The County includes a number of other models, including Child-First, an early childhood intervention program aimed at decreasing serious emotional disturbance, abuse, and neglect. It is an intense, six-month program that involves a caseworker, case manager, and clinical therapist. “Providers were seeing many more families struggling with domestic violence, substance abuse, and mental illness,” says Williams-Taylor, “and while the other programs do work to reduce abuse and neglect, there was just an influx of families that were needing intense mental health treatment. Child-First has really been shown to be effective in Connecticut where adults are grappling with domestic abuse and neglect.” Palm Beach County will be the first location to replicate the program outside of Connecticut.

Investing in Families

Home visiting programs like those in Baltimore and Palm Beach are win-win. Families that need and want help receive it, and taxpayers spend less on interventions later by investing up front in positive birth outcomes and early childhood experiences that prepare children (birth through age five) to enter kindergarten ready to learn. Researchers estimate that evidence-based home visiting programs save tax-payers money by decreasing the need for emergency room visits, child protective services, and special education. The Washington State Institute for Public Policy calculated a benefit-to-cost ratio of $2.69 for the Parents as Teachers home visiting program and a benefit-to-cost ratio of $1.17 for other home visiting programs as of July 2015.

Part of the reason home visiting programs are such a good investment is the strong evidence that they are improving lives for children and their families. In 2014, 14 of the MIECHV grantees reported development screening rates of at least 75 percent, which is more than twice the national average of 31 percent. This screening rate is significant as it means more children with developmental delays are being identified earlier, which translates into much better long-term outcomes for those children. Increased screenings for intimate partner violence were also seen in 2014, from a national average of up to 41 percent of physicians screening for it to nearly 95 percent among 12 grantees. Screenings for maternal depression (which untreated is associated with poor birth outcomes and parenting behaviors) were given by less than half of physicians nationally, but increased to 95 percent for 7 grantees.

Home Visitors Change Lives

Lorena was only 13 years old and in the eighth grade when she found out she was pregnant. Her single mother was recovering from a health trauma, and the father of her unborn child was no longer in the picture. Lorena was confused and frightened, and unsure of how to take care of a baby. Her local health clinic encouraged her to enroll in the Nurse-Family Partnership home visiting program through St. Paul-Ramsey County Public Health. The program paired Lorena with a nurse home visitor, Sara. The two developed a strong relationship over time. Sara supported Lorena through pregnancy until her daughter Amy was born. Sara then visited both mother and child.

At these visits Sara and Lorena talked about health issues, child development, and parenting strategies. They also completed some essential parenting tasks together. As a 14-year-old-mother, Lorena was unprepared to navigate the health care system and social services by herself. So Sara sat next to Lorena, and together they made the necessary phone calls to obtain health insurance, access welfare benefits, and schedule Amy’s doctor appointments. Over time, Lorena developed more confidence. She now makes appointments by herself. At Sara’s encouraging, Lorena stayed in school and is making plans to attend college. Now age two, Amy is on track developmentally.

The birth of a child can be intimidating and overwhelming for even the most financially and emotionally secure of parents. For a family already struggling with finances, housing, physical or emotional health, domestic violence, or substance abuse, the stress of pregnancy and parenting can be a negative turning point for a mother and her a family. Home visiting can make the difference. Just ask Lorena.

Resources

Women’s Health Initiative, Bethesda, MD ■ Children’s Services Council www.cscpbc.org Boynton Beach, FL ■ Healthy Families America www.healthyfamiliesamerica.org Chicago, IL ■ Health Resources and Services Administration, Rockville, MD ■ Administration for Children and Families,Washington, DC ■ Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness Review, Washington, DC ■ Nurse-Family Partnership www.nursefamilypartnership.org Denver, CO ■ B’More for Healthy Babies www.healthybabiesbaltimore.com Baltimore, MD ■ Family League of Baltimore http://www.familyleague.org Baltimore, MD ■ Baltimore City Health Department; Baltimore, MD ■ Healthcare Access Maryland http://www.healthcareaccessmaryland.org Baltimore, MD ■ Child-First http://www.childfirst.com Shelton, CT ■ Washington State Institute for Public Policy http://www.wsipp.wa.gov Olympia, WA ■ Parents as Teachers http://www.parentsasteachers.org St. Louis, MO ■ St. Paul-Ramsey County Public Health, St. Paul, MN ■ Pew Charitable Trusts, Philadelphia, PA.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

‘Middle Class by Middle Age’:

Atlanta Nonprofit City of Refuge Uses Strategic Programming to Break the Cycle of Poverty for the Long-term

by Lauren Weiss

Atlanta, Georgia is a city in need of a solution.

Approximately 25 percent of the residents live below the poverty level and a 2014 Brookings Institute study found that between 2000 and 2011, the suburban poor population of Atlanta grew 159 percent. Over 88 percent of the metro area’s poor population resided in suburban areas outside of the city, where transportation can be limited, making steady work difficult to keep.

The 180° Kitchen at City of Refuge prepares 1,200 meals daily for the residents of Eden Village, a shelter for single women and their children. The kitchen is also home to the Culinary Arts School, a 12-week training program.

Atlanta is also home to the largest wealth disparity in the U.S. According to a Brookings Data Now report, the richest five percent of households earned more than $280,000, while the poorest 20 percent earned under $15,000. Atlanta recently ranked as one of the worst metro areas in the U.S. in terms of economic mobility for low-income families, which Brookings Institute researchers believe is partially due to the high levels of racial and economic segregation in the area.

A City of Refuge Is Born

Beginning as a feeding program in 1970, City of Refuge has evolved into a multi-faceted approach to intervening in and breaking the cycle of poverty.

The latest figures from the U.S. Census Bureau indicate that in zip code 30314, the home of City of Refuge’s more than 200,000 square foot campus, the need is even more acute. The area known as “the Bluff” has the highest crime rate per capita in Georgia, the highest rate of incarceration, the highest homeless population per capita, a less than 50 percent graduation rate, and a 40 percent unemployment rate. It is a community that has been plagued by poverty for decades.

Bolstered by their enormous space and the poverty surrounding them, City of Refuge knew they had to tackle an array of issues—not just food insecurity—in order to make a difference. Over the years, they opened a shelter, and their kitchen grew from simply serving the residents of their shelter system into a culinary school and catering enterprise. City of Refuge created programs to help single mother families, teen mothers, and children in their shelter and the surrounding community. They also partnered with the National Automotive Parts Association (NAPA) to run a mechanic training program.

In a city dubbed the “epicenter of suburban poverty in America” by the Brookings Institute, City of Refuge became an epicenter of innovative approaches to ending that poverty.

Strategizing a Brighter Tomorrow for Atlanta

Terry Tucker, the Chief Strategy Officer of City of Refuge, has been with the organization for the last three years. He began his work there serving on the Board of Directors, and as the organization began a recent rapid expansion of services, he was asked to step in and manage the growth of City of Refuge. When asked what his role entails, he chuckled and replied, “That is a loaded question!”

Being the Chief Strategy Officer, it turns out, entails doing almost everything outside of on-the-ground operations—though Tucker frequently steps in to be a part of those at events, as well, and can be spotted in the majority of event photos on the City of Refuge Facebook page. His office covers not only strategy to move the organization forward, but external relations, technology, program strategy, legal needs, and volunteer management.

“That is a big thing for us—middle class by middle age,” said Tucker. “Because if you reach that point, when you start your family, they are not born into a cycle of poverty that creates a whole cycle of need all over again.”

“City of Refuge is unique in the sense that it is probably one of the only nonprofits that I know of that has an office of strategy,” said Tucker. “When you are trying to make an impact, if your organization is not integrated across the functions, you are going to have people doing things that may be counterproductive to the true mission and the true overarching impact goals.”

By keeping nearly all operations under one umbrella, Tucker aims to form a cohesive environment in which all players are geared toward one mission: reduce the number of people who are experiencing or who will be born into poverty. On a more focused level, the goal at City of Refuge is for everyone who walks through their doors to reach middle class by middle age.

“That is a big thing for us—middle class by middle age,” said Tucker. “Because if you reach that point, when you start your family, they are not born into a cycle of poverty that creates a whole cycle of need all over again.”

City of Refuge built their model of intervention based on a 2012 Brookings Institute study entitled Pathways to the Middle Class. With this study as a guide, they decided on six key impact areas for interventions: housing, education, youth social and emotional development, health and wellness, vocational training, and social enterprise.

Better Yourself, Better the Community

‘Social enterprise’ is perhaps one of the most unique focus areas at City of Refuge. A social enterprise is a moneymaking venture operated by a nonprofit for the benefit of their core services and programs. Rather than stopping at vocational training, they have created two enterprises on their campus: 180° Kitchen and the NAPA Training Center. These are not training programs that merely simulate work experiences in the safety of a classroom. 180° Kitchen students cater events and run a bistro on campus; NAPA students operate a live auto shop and serve customers. Both programs focus on industries in Atlanta that are consistently in need of employees, so students graduate into a favorable job market upon completing their training.

“We know that in order for individuals and communities to be self sufficient, we need to have more jobs and products that benefit the social structure of the country or community,” said Tucker. “We can get someone a job somewhere, but if we can get them a job where they are actually working on a socially beneficial product or service, we are basically killing two or three birds with one stone.”

It is this kind of strategic thinking based on both individual and community needs that has made these young programs so enormously successful: graduates of the NAPA Training Center are guaranteed a position with NAPA, and there is a nearly 100 percent placement rate for graduates of 180° Kitchen’s Culinary Arts School.

Stepping into the 180° Kitchen

Behind the social enterprise of 180° Kitchen is the simple fact that started everything: people need to eat. City of Refuge needed to find a way to feed them that promoted healthy, happy living.

Serving the residents of Eden Village—a City of Refuge campus facility that provides shelter for single women and their children—is the primary focus of 180° Kitchen. Serving approximately 1,200 meals a day using food exclusively purchased from vendors, not donated, 180° Kitchen is all about promoting health and wellness for the City of Refuge residents.

Chef Juliet Peters teaches students culinary skills in the mornings, and in the afternoons they put those skills to the test preparing meals for residents.

With this kind of heavy demand for freshly prepared meals, a need arose for trained staff, and thus the Culinary Arts School was created. Chef Juliet Peters works with students in the morning teaching them baking, supervisory skills, basic sauces, food cost controls, proper preparation and fabrication of meats and vegetables, and how to make dishes that create a stir. In the afternoon they put their skills to the test preparing meals for residents. At the completion of the 12-week program, they take part in a job fair and showcase of their skills for local restaurants, and most receive multiple job offers from Atlanta businesses.

Outside of the residential food preparations, students have the opportunity to work in the kitchen of American Bistro, on-campus fine dining with a capacity of 120 people, a mobile food truck called The People’s Food Truck, and a catering business serving large visiting groups, construction workers on the new Mercedes-Benz Stadium in downtown Atlanta, and any others who require their services in the community.

As if this array of experiences were not impressive enough for students of the Culinary Arts Program, they have also had the privilege of having as their chief culinary officer Walter Scheib, former White House Executive Chef under Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. Scheib advised City of Refuge on improving the Culinary Arts Program, worked closely with students, and even brought students with him to his own large catered events to gain experience working in some of the most demanding catering environments in the country.

“He could be anywhere he wanted to be in the country, and he chose to come here and help these students who were in the 180° Kitchen regain some self sufficiency,” said Tucker. “People always asked him why he would do that given where he was, and he said he has cooked for people who have everything and it was a pleasure for him to be at a place where people were using the art of cooking to be able to get back to where they have something of their own.”

Tragically, Walter Scheib passed away in June of 2015, leaving behind a tremendous void for the students and staff who had grown to love working with him. They have since established the Walter Scheib Excellence in Culinary Arts Award and fund for the top student in each graduating class in his memory.

“Now you say, well how do you fill a void like that? Outside of him being my good friend and just mourning over the loss of him, obviously from a City of Refuge perspective that came across my mind,” said Tucker. “Fortunately, I did not have to think very long.”

Within a few weeks, calls poured in from the White House, from chefs who had worked with Scheib over the years and wanted to carry on his legacy at City of Refuge. In the coming months, they will take on a new chief culinary officer who will continue the work of refining the American Bistro and guiding the students of the Culinary Arts Program.

NAPA Training Center On-Site that Benefits Residents and Those in the Community

Still located on the campus of City of Refuge, but tackling the areas of vocational training and social enterprise in a wholly different way, is the NAPA Auto Repair Training Center. Here, 14 students per session undergo an intensive 40-hour a week, six-month course ending in guaranteed employment with NAPA if they complete the certification and meet the course requirements. This symbiotic relationship allows the Center to have knowledgeable instructors while NAPA is ensured their new employees are trained properly to serve their customers effectively.

The NAPA Auto Repair Training Center on the City of Refuge Campus enrolls 14 students per session in an intensive 40-hour a week, six-month course. Course graduates are guaranteed employment with NAPA if they complete the certification and meet course requirements.

The Center focuses on recruiting and enrolling those in the community who might benefit most from this valuable training: veterans returning from military duty and seeking re-training in mechanics; those re-entering society following incarceration or rehabilitation and seeking opportunities with a certified training center; and students enrolled in City of Refuge’s on-campus private school for middle and high school aged students, Bright Futures Academy, wishing to enter vocational training. Students spend the morning in the classroom or learning online, and in the afternoon they complete in-shop training on a wide range of auto repairs and diagnostics.

As of summer 2015, the Center has graduated one adult class and started its second adult class and the two-year part time high school program. So far, it has proven a success. Retention and completion are high, and the Center continues to grow with state of the art tools, lifts, and parts to operate as a functioning auto shop serving the local community. As students continue to complete the program, Tucker is hoping the Center will be able to break even on operating costs and eventually generate a self-sustaining profit that will allow the Center to gain even more equipment and instructors.

Students are not relegated exclusively to a position as a mechanic; they are also qualified to work retail parts jobs for NAPA, and learn how to interact with customers beyond just repairing their cars.

Ruben Williams, a classroom instructor in the Center, has watched the program evolve, but knows there is still much work to be done.

“When we first started we did not have computers, but now we do. We have NAPA online, which is a big help,” said Williams. “Since this is a new program, a lot of materials and things that are needed, they do not have. But everything is getting better.”

Rather than stopping at vocational training, they have created two enterprises on their campus: 180° Kitchen and the NAPA Training Center. These are not training programs that merely simulate work experiences in the safety of a classroom. 180° Kitchen students cater events and run a bistro on campus; NAPA students operate a live auto shop and serve customers.

Another important feature of the training is that it covers a broad range of skills needed by NAPA and by any service center in the country. Students are not relegated exclusively to a position as a mechanic; they are also qualified to work retail parts jobs for NAPA, and learn how to interact with customers beyond just repairing their cars.

One of the graduates of the first class now works as a delivery driver for NAPA, bringing auto parts to the Center on a regular basis. She has been promoted several times, and students currently enrolled are able to see definitively what sticking with the course can mean. For people who have lived with financial uncertainty, whether they are veterans or students who have lived in poverty their entire life, seeing someone who has followed their current path to completion can be an important motivator. Obtaining certification and a job from NAPA means financial stability, self-sufficiency, and regaining a sense of control.

“They are taking people from the neighborhood who may not have a chance to get this type of training on their own. … I am hoping that maybe we can tweak the program to where instead of having just two graduating classes each year, maybe we can have three or four,” said Williams. “I hope [my students] take the sense that they were given something, and in the future they can give back.”

After completing the 12-week training program, at 180° Kitchen students take part in a job fair and showcase of their skills for local restaurants. Most students receive multiple job offers.

The Intervention Machine

Beyond the 180° Kitchen and NAPA Auto Repair Training Center, City of Refuge has a roster of services reaching every kind of need. The Kindred Spirit Home takes in single teenage mothers, during their pregnancy and the first year after birth, to teach them valuable parenting skills and put them on a path to self-sufficiency and independent living. Their educational programs serve children from toddlers to teens, catering to their social and emotional development as well as their health. Eden Village provides single mothers and their families with emergency temporary shelter as well as long-term shelter and counseling services. Their internship program challenges teens to think about their community and strive for greatness.

On the sprawling campus of City of Refuge, it is clear that creativity is embraced in their search for strategic interventions that will be effective for both their clients and their community.

Resources

Brookings Institute http://www.brookings.edu Washington, DC ■ City of Refuge http://cityofrefugeatl.org Atlanta, GA ■ U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC ■ National Automotive Parts Association http://www.napaonline.com Woodbury, CT.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Databank

Resources

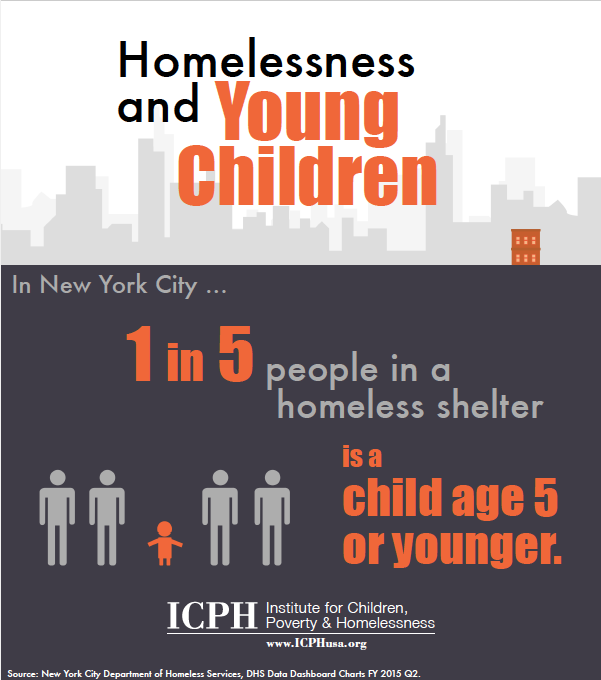

New York City Department of Homeless Services, DHS Data Dashboard Charts FY 2015 Q2.

To download a pdf of Databank, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

National Perspective—

How Effective is Your Community at Identifying Homeless Children?

by Matt Adams

It is relatively straightforward to determine the number of children who are living in shelter. However, it is much more difficult to assess the number living night-to-night in a hotel or motel (because that is the only housing their parents can afford), doubled up with another family member or nonrelative (because they cannot pay for their own place to live), or on the streets. Children without stable homes are at greater risk for worse academic outcomes than those with permanent places to live, but all too often they are not identified and remain disconnected from the services that would help them thrive in school. With this in mind, the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH) developed a ranking system to measure how well states are identifying and providing services to homeless children from birth through young adulthood.

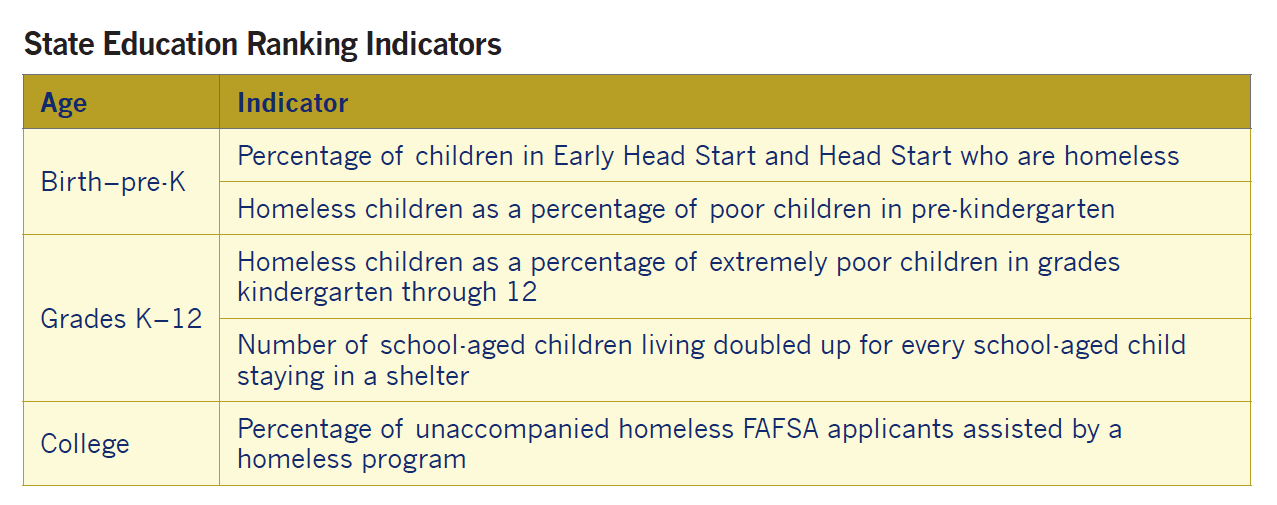

The State Education Rankings, released as part of the 2015 American Almanac of Family Homelessness, use publicly available data to illustrate important differences among states, but more detailed information is often available within states that can be used to determine progress at the district, school, or program level. ICPH hopes that states and communities will use their local data to discover what some programs are doing well and to improve those that may be underperforming. The five indicators that comprise the State Education Rankings, arranged by target age group, are shown in the following table:

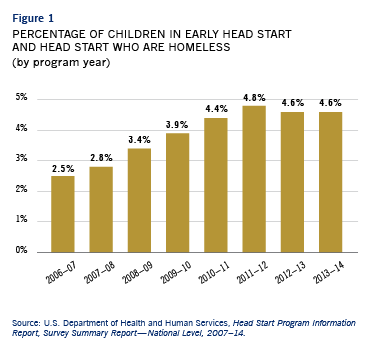

Increasing young homeless children’s enrollment in high-quality early education programs can help prepare them for school and position them for success later in life. Low-income children who participate in high-quality early childhood education programs are more likely to graduate from high school, be employed, and have higher earnings as adults. Since a federal effort was made to enroll young homeless children in Early Head Start and Head Start, the percentage of participating children who are homeless increased from 2.5% in program year 2006–07 to 4.6% in 2013–14 (Figure 1).

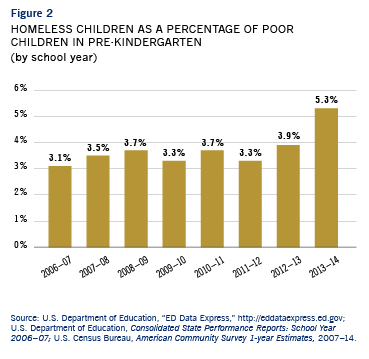

Head Start State Collaboration Offices can work to further increase enrollment by targeting local programs where the percentage of homeless children served is low. Other high-quality early childhood education programs, administered primarily by states, can do the same. Comparing the number of homeless children attending pre-K with those who are poor indicates how well homeless children are being identified. Nationwide, 5.3% of all poor children enrolled in pre-K also experienced homelessness during the 2013–14 school year (Figure 2).

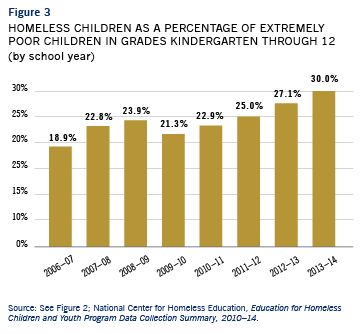

A similar approach can be undertaken to increase the number of homeless students identified in elementary and secondary schools. As with pre-K, state and local educational agencies can compare the number of homeless students to the number of school-aged children who are extremely poor (living at or below 50% of the poverty level, which amounted to $9,895 for a family of three in 2014). Nationally, 30.0% of all extremely poor students were homeless during school year 2013–14 (Figure 3).

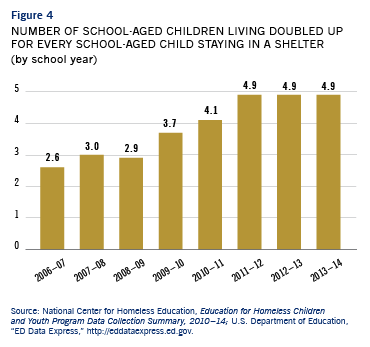

Since homeless children living doubled up for economic reasons are challenging to identify, school administrators can use a second, complementary measure to ensure that more homeless students receive essential services. Dividing the total number of doubled-up students by those living in shelter can help determine jurisdictions that are likely not as effective at identifying homeless students in doubled-up situations. Nationally, for every student living in a shelter, there were nearly five (4.9) staying doubled up during the 2013–14 school year (Figure 4).

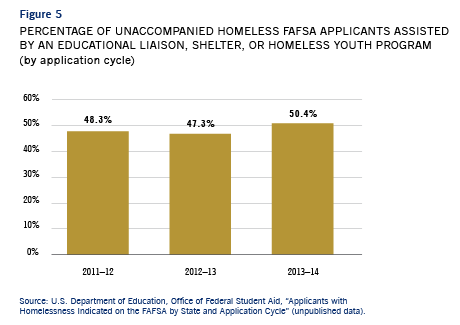

The only national data on college students experiencing homelessness is collected through the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA). Homeless youth who are unaccompanied by a parent or guardian do not have to provide their parents’ financial information if their situation is verified by a school district homeless liaison or by the director of a U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development-funded shelter or Runaway and Homeless Youth program. College financial aid administrators must make a determination for youth who do not have access to one of these three authorities. Half (50.4%) of all unaccompanied homeless students who filed the FAFSA during the 2013–14 application cycle were verified as independent students, considerably reducing their likelihood of securing the financial aid necessary to help make college a reality (Figure 5).

For the State Education Rankings, ICPH carefully selected five indicators that directly relate to actions that can be taken to improve access to education for homeless children of all ages. ICPH hopes that administrators at the state, district, school, or individual program level will find these indicators to be a valuable way to measure how well—and how many—homeless children are currently being served. Using local data would reveal the differences in the student homelessness landscape within communities and enable resources, technical assistance, and support with outreach and identification to be targeted more effectively to localities with the greatest need.

For the State Education Rankings, ICPH carefully selected five indicators that directly relate to actions that can be taken to improve access to education for homeless children of all ages. ICPH hopes that administrators at the state, district, school, or individual program level will find these indicators to be a valuable way to measure how well—and how many—homeless children are currently being served. Using local data would reveal the differences in the student homelessness landscape within communities and enable resources, technical assistance, and support with outreach and identification to be targeted more effectively to localities with the greatest need.

Resources

Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, American Almanac of Family Homelessness, 2015 ■ U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Head Start Program Information Report, Survey Summary Report—National Level, 2007–14 ■ U.S. Department of Education, “ED Data Express.” ■ U.S. Department of Education, Consolidated State Performance Reports: School Year 2006–07 ■ U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 1-year Estimates, 2007–14 ■ National Center for Homeless Education, Education for Homeless Children and Youth Program Data Collection Summary, 2010–14 ■ U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid, “Applicants with Homelessness Indicated on the FAFSA by State and Application Cycle” (unpublished data).

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Eating Well Should Be a SNAP

by Mari Rich

The link between being overweight or obese and being food insecure (defined as being without access to enough appropriate food for an active, healthy lifestyle) has been widely studied, with nutrition and policy experts in agreement that the situation imposes a great strain on public well-being and the nation’s healthcare system.

Low-income neighborhoods often lack full-service grocery stores or farmers’ markets at which residents can buy a variety of wholesome food, and residents must rely on small corner stores (bodegas) or fast-food outlets, which peddle high-calorie, low-nutrient products.

Thanks to initiatives like mobile farmers’ markets, community garden programs, and dollar-for-dollar incentives that effectively halve the cost of fresh produce for those using the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), commonly known as food stamps, or the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) in some areas, that situation is slowly changing. Still, just because good, healthy food becomes widely available, does not mean that everyone will know how to prepare it. According to “It’s Dinnertime: A Report on Low-Income Families’ Efforts to Plan, Shop for, and Cook Healthy Meals,” which was prepared by the national nonprofit group Share Our Strength, 85 percent of the low-income people they surveyed believed that healthy meals were important, but 78 percent admitted that they needed to learn more about how to prepare those meals.

While being faced with Swiss chard or parsnips for the first time can be intimidating, there are cookbooks and classes that can help.

Tasty, Nutritious, and under $4 a Day

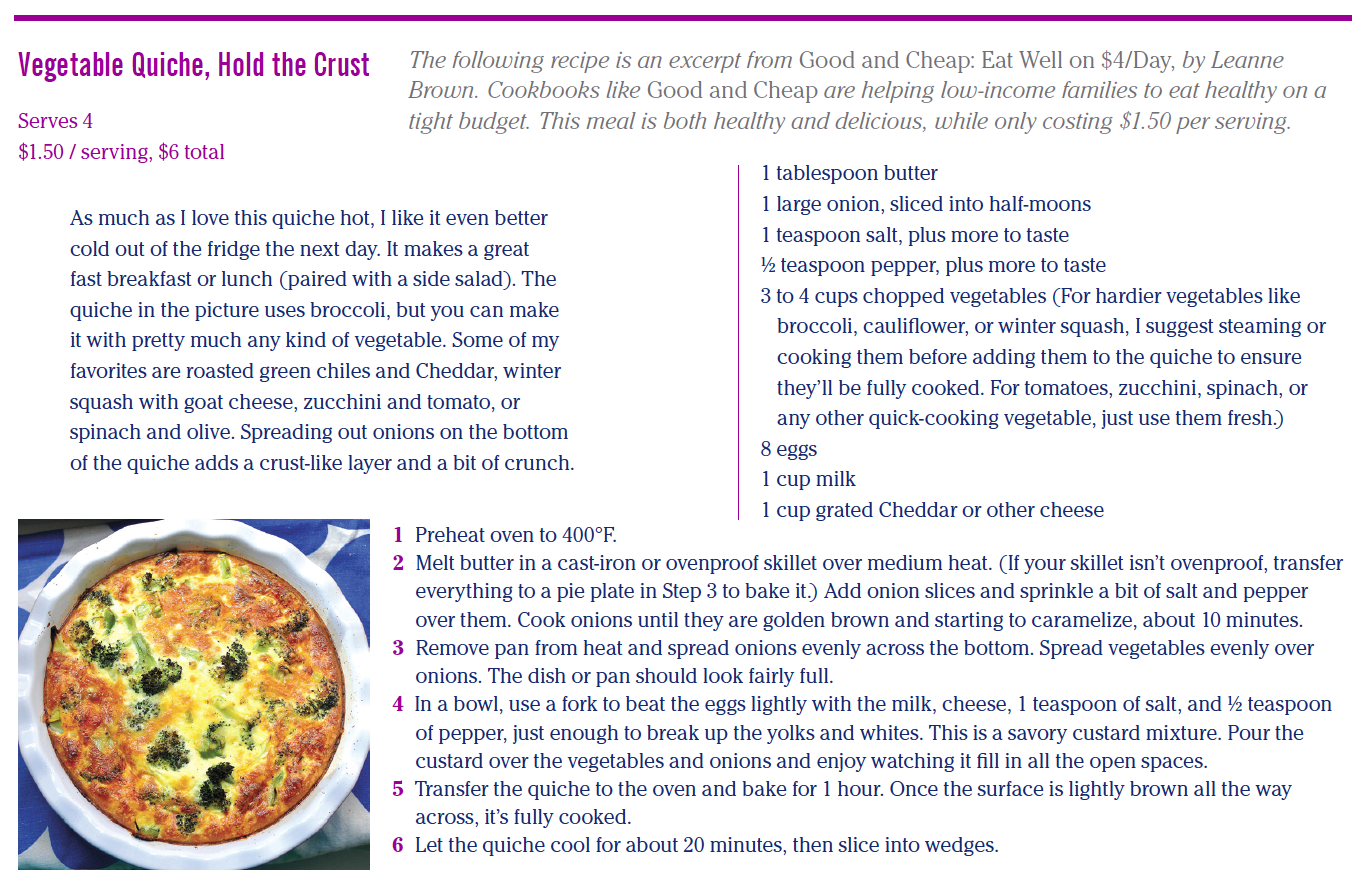

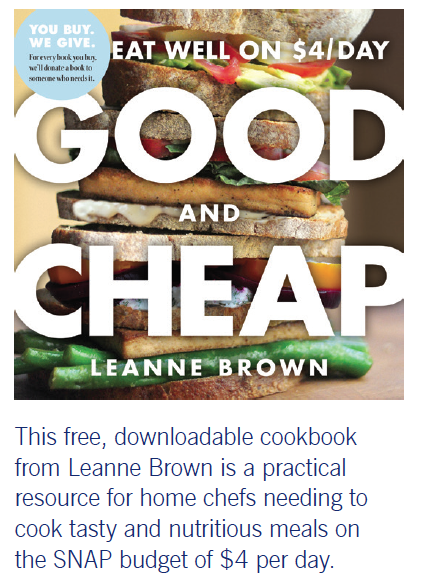

Leanne Brown was majoring in Food Studies at New York University when she decided to tackle a vexing question. Was it possible to prepare delicious, healthy meals on a budget of about $4 a day, the amount allotted per person on SNAP?

As a graduation project, she developed a set of recipes—colorful, loaded with vegetables, and economical—and prepared a beautifully illustrated PDF, which she made available for free online at www.leannebrown.com. Good and Cheap: Eat Well on $4/Day, as she called the collection, quickly went viral, with so many hundreds of thousands of people downloading it that her site crashed multiple times. Realizing that she had struck a chord, Brown mounted a Kickstarter campaign to fund a print run: if a supporter purchased a print edition of the book, which includes such recipes as Broiled Tilapia with Lime, Spicy Pulled Pork, and Green Chile and Cheddar Quesadillas, she would provide a printed copy to someone with limited or no computer access for free.

To date, she has given more than 12,000 printed copies of Good and Cheap to organizations across North America that work with low-income families, and she has entered into an agreement with Workman Publishing, an independent publisher of adult and juvenile trade books, that promises to get tens of thousands of additional copies into the hands of those in need. “So many people on SNAP have dietary restrictions, or live in food deserts, or do not have a proper kitchen, and even the best cookbook cannot solve those problems,” she has said. “But if I can help only one percent of the 46 million people on food stamps, that is still 460,000 people.”

The Benefit of First-Hand Experience

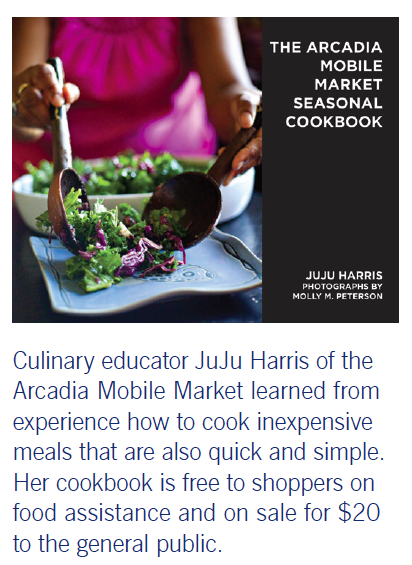

JuJu Harris is a culinary educator and SNAP outreach coordinator with the Arcadia Center for Sustainable Food and Agriculture, a nonprofit seeking to create a more equitable food system in the Washington, D.C. area.

Much of the wisdom she passes on to her clients was gained through personal experience; Harris relied on food assistance during a particularly difficult period. She now travels with Arcadia’s Mobile Market, a brightly painted school bus that functions as a farmers’ market on wheels. Once set up at a location, she demonstrates recipes to those who might never before have known how to prepare squash or realized that carrots come in colors besides orange. “I teach them what I call my gospel,” she says, “which is that healthy eating doesn’t have to be expensive, difficult, or time-consuming.”

In 2014 Harris had the idea of putting together a basic cookbook to hand out to Mobile Market shoppers, but her co-workers were so excited by the idea that it mushroomed. With the help of a team of volunteers (and a generous grant), she created The Arcadia Mobile Market Seasonal Cookbook, a lavish, fully illustrated volume available to Mobile Market shoppers on food assistance for free and to the general public for $20 a copy.

Deciding What Matters

On occasion, JuJu Harris has taught classes based on an engaging curriculum developed by Cooking Matters, an initiative of the nonprofit group Share Our Strength. Founded in 1993, Cooking Matters is based on the premise that if people are taught how to shop carefully and prepare meals skillfully, they will be healthier and happier.

To that end, Cooking Matters mounts interactive grocery store tours that provide shoppers with hands-on education, giving them the knowledge to compare foods for cost and nutrition. The initiative also includes cooking classes, which meet for two hours, once a week for six weeks. Taught by volunteer chefs and nutrition educators, the classes cover such skills as proper knife techniques and what to do with a whole chicken.

Cooking Matters honors volunteers who teach at least 15 six-week courses with induction into a “Hall of Fame,” but David Coder, a chef who was inducted in 2011 and now sits on a Cooking Matters advisory board has said, “The moms who commit to six weeks to feed their families better; the teens who run into class to be the first ones to wash their hands; and the proud wife who told me that her husband lost 60 pounds because of the way she now cooks—those are the people in my hall of fame.”

Resources

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; Alexandria, VA ■ Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; Alexandria, VA ■ Share Our Strength; Washington, DC ■ Leanne Brown www.leannebrown.com New York, NY ■ Arcadia Center for Sustainable Food and Agriculture http://arcadiafood.org Alexandria,VA ■ Cooking Matters http://cookingmatters.org Washington, DC.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

About UNCENSORED

Fall 2016, Vol. 6.3

FEATURES

The Digital Divide: Bringing Low-Income Students to the Cutting Edge of Technology

Changing Lives with a Knock on the Door: Home Visiting Programs for Struggling Families

‘Middle Class by Middle Age’: Atlanta Nonprofit City of Refuge Uses Strategic Planning to Break the Cycle of Poverty for the Long-term

EDITORIALS AND COLUMNS

Databank—Homelessness and Young Children

The National Perspective—How Effective Is Your Community at Identifying Homeless Children?

Eating Well Should Be a SNAP

Cover: Technology has been hailed as an equalizer of educational opportunity. However, low-income students often do not have the same access to technology as their more affluent peers.

50 Cooper Square, New York, NY 10003

T 212.358.8086 F 212.358.8090

Publisher Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD

Editors Linda Bazerjian

Assistant Editor Katie Linek

Art Director Alice Fisk MacKenzie

Editorial Staff Matt Adams

Contributors Lauren Blundin, Mari Rich, Lauren Weiss

UNCENSORED would like to thank Leanne Brown; JuJu Harris; Digital Promise; Girlstart; Homes for the Homeless; Women’s Health Initiative; and City of Refuge for providing photographs for use in this publication.

Letters to the Editor: We welcome letters, articles, press releases, ideas, and submissions. Please send them to info@ICPHusa.org. Visit our website to download or order publications and to sign up for our mailing list: www.ICPHusa.org.

UNCENSORED is published by the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH). ICPH is an independent, New York City-based public policy organization that works on the issues of poverty and family homelessness. Please visit our website for more information: www.ICPHusa.org. Copyright ©2015. All rights reserved. No portion or portions of this publication may be reprinted without the express permission of the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness or its affiliates.

![]() ICPH_homeless

ICPH_homeless

![]() InstituteforChildrenandPoverty

InstituteforChildrenandPoverty

![]() icph_usa

icph_usa

![]() ICPHusa

ICPHusa