Publisher’s Note

Dear Reader,

As we embark on our third year of publication, we welcome both regular readers and new ones, and hope that you find the Spring 2012 issue to be informative and thought-provoking.

Our On the Homefront section will give you a glimpse of the people, topics, and ideas covered at ICPH’s conference held earlier this year, “Beyond Housing: A National Conversation on Child Homelessness and Poverty.” We hope you’ll join us for our next conference in New York City in 2014. One of the standout workshops at the conference was on trauma-informed care, so we decided to ask our panelists to go On the Record to share their insights into this promising service-delivery approach. And in UNCENSORED’s tradition of dealing with the difficult topics that often are not talked about, we take a look at the relationship between race and homelessness.

This issue’s cover story delves into local programs and national trends to provide better access to and awareness of healthy foods and food preparation—from rooftop gardens to mobile produce deliveries and junior chefs. Another feature article chronicles homeless, formerly homeless, and foster-care youth as they speak for themselves, taking to the streets, the airwaves, and government offices to make change. Post-recession personal and family finances are top-of-mind, and so is the movement for financial literacy, especially among low-income families, in our story about financial literacy courses and awareness around the nation.

Finally, in this issue we bring you a Guest Voices column in both words and photos from advocate and documentarian Diane Nilan, founder of Hear Us, who travels the country in her RV giving voice to homeless children and families by telling their stories.

In the pages of UNCENSORED, you will find we continue to confront tough questions and keep the dialogue going about families and children experiencing poverty and homelessness in America. We welcome your feedback at info@ICPHusa.org.

Sincerely,

Ralph da Costa Nunez, Publisher

President and CEO, Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Grass Roots:

Innovative Food Education Programs Empower Communities to Take Nutrition into Their Own Hands

by Lee Erica Elder

Nutrition education is changing, plate by plate. It is happening around the country—on rooftop farms, at food tastings and demonstrations, farmers’ markets and community chef training classes. Increasingly, community food education programs offer nutrition and wellness learning through interactive and innovative approaches. By addressing the distinct needs and circumstances of their respective populations, these grassroots initiatives teach the skills to grow, select, prepare, and understand food from the ground up, allowing participants to actively redefine their health and move beyond the statistics and stigma that often narrowly define their experiences. This systematic programming provides layers of tangible tools and support to inspire significant change in the way participants view food and nutrition, and the budgeting of their food dollars. The timing of the surge couldn’t be more appropriate: as of 2010, according to Feeding America, 17.2 million American households were food-insecure, meaning they were uncertain where their next meals would come from—the highest number ever recorded in the United States. The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that 17 million American children—nearly one in four—have limited or uncertain access to affordable, nutritious food.

The Brooklyn Grange rooftop farm serves as an incubator of knowledge for the children in the City Growers education program as they examine insects and plants that they have never encountered.

Rebecca Lemos and Lola Bloom began gardening with children at CentroNia, a community-based education center in the Columbia Heights area of Washington, D.C., while still in high school. Believing that all children and families should have access to natural spaces, the duo continued their work throughout college and post-graduation, and in 2003, City Blossoms was born. City Blossoms creates Community Green Spaces in low-income neighborhoods, offers workshops at schools and community organizations, and leads professional development trainings. “Our model uses the garden to teach artistic expression, healthy living skills, eco-literacy, and community building,” Bloom says. Kids participate in botanical drawing; prepare summer rolls, salsa, pesto, and mixed salads using freshly harvested ingredients; and through an Herbal Entrepreneurship program, cultivate, harvest, and use herbs to create products to sell at farmers’ markets. “Food is a common language that can be used to create strong community bonds—and it’s way easier to attract people to healthy habits through cooking than through lectures,” says Bloom. “We try to meet people where they are, think about food more holistically, and approach people from their interests, rather than hammering them over the head with what ‘should’ be in their diets.” City Blossoms created ten new school gardens in the last year, and counts children of program alumni among current participants.

Not far from City Blossoms is a national symbol of the growing movement for sustainability and healthy eating—the White House vegetable garden, which broke ground in 2009. First Lady Michelle Obama conceived of the all-organic garden—which also supplies food to local food banks and soup kitchens—when she felt her own daughters’ meals were not nutritious enough. For many D.C.-area children, the need for healthy food is dire—the area has the highest national rate (32.3%) of children in households without consistent access to food, according to Feeding America. According to D.C. Hunger Solutions, 43% of all D.C. school-age children are obese or overweight, 81% of children do not consume the USDA-recommended five fruits and vegetables a day, and estimated annual health care costs associated with obesity in D.C. are $372 million and rising. The White House Garden, Obama’s “Let’s Move!” campaign, and D.C.’s 2010 Healthy Schools Act—efforts sharing a focus on wellness education for children through a variety of means—bring national attention to the need for a re-imagining of the nutrition landscape.

Garden on the Go of Indianapolis brings fresh and affordable produce to people who live in areas where fruits and vegetables are not easily accessible. Half of their stops serve seniors who are physically unable to travel and cannot afford produce in grocery stores.

In New York City, a unique nonprofit educational program, City Growers, thrives in an unconventional space at Brooklyn Grange, a one-acre rooftop farm in Long Island City. “Because ground-level space in the inner city is so limited and expensive, rooftop farms present a viable option for city farm and community garden projects,” says Gwen Schantz, co-founder. Visiting students, many from Title I schools (those with a high percentage of students from low-income families), explore farming, gardening, and their role in the environment. The experience is illuminating. “Kids are a little more connected to junk food that they eat than they are to vegetables and fruits,” says co-founder Anastasia Plakias. “They’re able to connect with junk food products on a brand level—there’s a face for McDonalds, Kentucky Fried Chicken—these are iconic brand representations. For many kids, pulling a carrot out of the ground is a brand-new experience. When they feel that carrot in their hands, feel the dirt give way underneath, then taste that really sweet fresh vegetable, it’s an eye-opener.” Plakias acknowledges that even among those who can afford to regularly buy healthy produce, a real appreciation of where food comes from “is sorely lacking in our community.” She hopes this hands-on experience inspires informed and independent eating choices. “It’s so important to connect kids with food at this stage of their lives because they are growing and their bodies are changing, and they are really curious about that. Kids are all about having a tactile and visceral understanding of the world around them, and you can only impart so much information intellectually—they need to connect with the subject matter.” She shares a comment from a letter written by a visitor from Upward Bound, a college-prep program for students from low-income families: “I learned a lot, such that it is good to buy food locally, and that these rooftop farms help the economy of the community by giving people jobs, and there are little to no greenhouse gases or fossil fuels used.”

When nutritionist and chef Gina Keatley, founder of Nourishing NYC, lived in East Harlem while attending New York University, she was shaken by the grave income disparities between her neighborhood and those just a few miles further downtown. East Harlem has some of the highest rates of hunger and obesity in the city, and according to the U.S. Census, 34% of residents claim disability (the national average is 19%). “Seeing men and women in their early 30s and even younger, missing limbs or living their lives in wheelchairs or with walkers, I realized quickly that their mobility and health issues were directly related to complications from diabetes and obesity,” Keatley says. “Living in a food desert, it seemed obvious: poverty was directly linked to the ability to access healthy and nutritious sources of foods. I immediately knew that I had to do something to address the direct correlation between health and low-income status.” The immediacy was intensely personal; Keatley experienced poverty and homelessness as a child. Nourishing NYC’s Urban Produce Program distributes thousands of pounds of fresh produce annually to New York City residents, and provides community education through its junior chef program and nutrition classes. “Through Nourishing NYC’s nutrition, health, and anti-hunger advocacy programs, we begin to approach people on a human level, where we are learning and growing together to strengthen families and communities,” Keatley says. “Giving people the tools to make their own healthy foods at home, showing them through demos and cooking classes, as well as letting them taste and smell the ingredients as they interact with one another, works wonders.

This vibrant mural by Max Bode helps children understand the stages of composting, which they can also witness firsthand on the Brooklyn Grange rooftop farm.

Keatley has been honored as a CNN Hero and a L’Oréal Paris Woman of Worth, but perhaps some of her most rewarding acknowledgements are the junior chefs who look up to her, like 13-year-old Hinda Diakite. “It was a wonderful experience,” she says, of the weekend cooking classes, community service projects, and especially a Thanksgiving meal workshop. “I plan to continue working with Nourishing NYC. Community food education programs are important, because they educate people on the right things to eat and how to live a happy and healthy lifestyle. My goals are to get into Food and Finance High School, and then attend culinary school. I hope to open my own restaurant or bakery one day.” Nourishing NYC recently launched Nourishing USA, creating Anti-Hunger Advocacy Kits for people around the country who want to start their own self-sustaining community gardens and initiatives.

Targeting preparation of the family meal, many programs encourage the integration of healthy cooking skills into existing traditions. Just Food, a New York City-based organization, which has supported community-sustained agriculture programs, community-run farmers’ markets, and farm-to-food pantry programs since 1995, began community food education programs to close the gap between access to local and organic food, and consumption. “Research shows that it’s not just an issue of access—access doesn’t mean you are going to make the right choices,” says Angela Davis, Just Food community food education program coordinator. To address these needs, the organization works within the local framework to create a space for engagement, training community chefs and gardeners to conduct workshops and demonstrations in their communities. “Our goal is to see what is already happening in the community and providing the training to amplify what they’re already doing,” says Davis. “It’s about planting a seed with people, getting them used to things they hadn’t heard of before or cooking things in a different way.” The task of encouraging lifestyle changes is a marathon, not a sprint, and community chefs are tasked with keeping people interested in preparing their own food on a regular basis. “Many people see cooking as a burden,” says Davis. “We compete against fast food and things like the 99 cents menu, which are cheap and don’t require any effort. To be healthy, to eat well and deal with issues of chronic diseases and take charge of your own health, doesn’t mean every meal has to be from scratch, but the majority should, because you can’t control what’s in your food when eating out. Our trainers pick ingredients that are affordable, which is definitely a challenge. We always have a recipe that they can try at home.” Participants enjoy the innovative demonstrations (a popular session teaches moms to make their own baby food) and the community chefs have even developed their own followings.

The Chinese American Planning Council’s Youth Green Team receives hands-on learning experiences at the Brooklyn Grange to accompany their studies on urban agriculture.

Loss of control over meal preparation can be devastating for those living in shelters. To address this need, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) Homeless Health Initiative (HHI) implemented a nutrition education and fitness promotion program supported by hundreds of volunteers, including doctors, nurses, and social workers, at three local shelters. Operation CHOICES is now in its third year of operation. “When we conducted focus groups with moms, they shared very strong emotions around food,” says Social Work Trainer Melissa Berrios. “They can no longer provide nourishment for their children—the love that moms pour into preparing a meal for their family, knowing exactly what their children like and don’t like to eat, delighting in the smiles and satisfaction on their faces when full from mama’s specialty.”

Weekly Operation CHOICES sessions with moms include fitness activities and interactive nutrition education, including lessons on basic food groups, nutrition labels, serving sizes, vitamins, minerals, and health consequences of obesity. The children’s nutrition curriculum covers creating healthy, balanced plates and the importance of fruits and vegetables. “It is important that we don’t label foods as good vs. bad—instead, we discuss how to make healthier choices and the importance of eating certain foods in moderation,” says Berrios. “We recognize that our families have limited resources and we don’t want them to feel like failures because they can’t easily access or afford fresh, organic produce on their way to the shelter from school. We want them to experience the power of successfully picking out snacks from the corner store that have less sugar or salt than what they may have chosen before. One mom shared with us that her son is now cutting off the fat on his meat at dinner in the shelter. One of our shelter partners offers a food tasting to families before deciding to add the new item to the menu.”

The program also preps parents for moves into transitional and permanent housing, accompanying them to local grocery stores to practice reading labels to make healthier choices and shopping the perimeter of the store for fresher options. “Operation CHOICES empowers those living in shelter and experiencing feelings of hopelessness, to recognize opportunities to gain control over their lives by making choices to improve their health,” says Berrios.

A thankful family leaves the Garden on the Go stand in Indianapolis with bags of fresh produce. Garden on the Go offers produce that is of higher quality than what is found in local grocery stores, so it stays fresh for a longer period of time, enabling families to maximize the money they spend on food.

Indiana has the 15th-highest obesity rate in the nation, but in just under a year, a groundbreaking partnership between Indiana University Health and the Green Bean Delivery Program has created hope for significant change. The first of its kind between healthcare and nonprofit organizations, Garden on the Go brings fresh, healthy, and affordable produce into food deserts in the Marion County area. “In our community, only about 25% of residents consume produce on a regular basis—that’s just not enough,” says Lisa Cole, manager of Indianapolis community outreach for Indiana University Health. The program launched in May of 2011, and results are already impressive—7,300 point-of-sales transactions in seven months. “It’s a regular route, Wednesday–Saturday, 16 stops per week. Ninety percent of participants say it has increased the amount of produce they eat,” says Cole. “Prior to Garden on the Go, one of our customers, a 44-year woman, both diabetic and a double amputee, was maybe able to get produce on a monthly basis. Now she can access produce on a weekly basis.” Says Lincoln Saunders, director of Garden on the Go, “If you’re in a motorized scooter or wheelchair, the grocery store that is two blocks away might as well be two miles away.” With half of the stops serving seniors, Garden on the Go’s efforts have already caught the attention of the Partnership on Aging. “Senior hunger is a huge issue,” says Cole.

Garden on the Go’s produce is beautiful and affordable. “This is very different from what they might find at a convenience store or box store,” says Cole. “The quality is so high that customers can maximize their food dollars better because it lasts longer.” The program was advised to charge for produce to connect customers with the solutions to their health issues and the importance of budgeting food dollars. At press time, about $4.95 bought a pound of green beans, a pound of bananas, three pounds of potatoes, a couple of apples, and a head of lettuce—this number was closer to $7.00 at the start of the program. Customers stock up on green peppers, priced at just 40 cents each, stretching them to create family- and budget-friendly meals such as stuffed peppers. “We think about what we carry on the truck as a great opportunity to deal with chronic health issues that we are trying to prevent or cope with,” says Saunders. “One gentleman said it was the best-looking produce since his own farm he grew up on as a child.”

Nourishing NYC distributes thousands of pounds of free produce to New York City residents who otherwise would not be able to afford nutritious fruits and vegetables.

Community food education programs are growing in number, as a critical response to unprecedented rates of poverty, obesity, malnutrition, and chronic disease in the United States. These movements bring much-needed attention to issues of homelessness and poverty, offer the possibility for increased health and longevity, and may even move people out of generational poverty. If programs continue to address the variety of issues created by food insecurity, and place the power of natural health in the hands of communities, change is possible. “I think these programs have the power to create changes in partnership with policy changes across the country related to food economics, community health, school foods, and urban agriculture,” says Bloom.

Corporate and media attention to these issues is at an all-time high. In 2011, Sesame Street got in on the act, with a Walmart-sponsored special, Growing Hope Against Hunger, introducing an impoverished puppet, Lily, whose family struggles with food insecurity.

“More not-for-profits should look for corporate entities to partner with,” says Cole. “If everybody can bring something to the table, that’s reasonable and sustainable over time. You have to have these efforts crossing over each other,” she says. “We have a responsibility to deal with the health of our community. The time is right for this kind of thing. Resistance that we’ve seen is, ‘What kind of data can you share with us?’ You don’t see changes overnight, but if you wait, how many trucks could have been started? This is a national problem, and it’s a complicated problem. To see the faces of these individuals that come off a truck with fresh produce loaded in their bags in a way they haven’t been able to before, I can’t translate that into data—but, if we come every week, it is going to make a difference.”

Critical Stats Linking Nutrition and Obesity in Children and Adults

National Center on Family Homelessness:

- Children experiencing homelessness are sick four times more often than other children.

- They go hungry at twice the rate of other children.

- Nutritional deficiencies in homeless children often lead to increased rates of being overweight and obese.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:

- There are much higher rates of obesity observed at every age of children experiencing homelessness than in other populations.

- About one-third of U.S. adults (33.8%) are obese.

- Approximately 17% (or 12.5 million) of children and adolescents aged 2–19 years are obese.

- Since 1980, obesity prevalence among children and adolescents has almost tripled.

- There are significant racial and ethnic disparities in obesity prevalence among U.S. children and adolescents. In 2007–08, Hispanic boys aged 2–19 years were significantly more likely to be obese than non-Hispanic white boys, and non-Hispanic black girls were significantly more likely to be obese than non-Hispanic white girls.

- Obese children are more likely to have high blood pressure and high cholesterol, which are risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD). In one study, 70% of obese children had at least one CVD risk factor, and 39% had two or more.

- Obese children are at greater risk of social and psychological problems, such as discrimination and poor self-esteem, which can continue into adulthood.

Children’s Health Fund:

- Obese children may show other signs of poor nutrition, including iron deficiency and anemia.

- For low-income children, obesity may be associated with household food insecurity.

Resources

New York City Coalition Against Hunger; New York, NY ■ Feeding America; www.feedingamerica.org, Chicago, IL ■ U.S. Department of Agriculture; www.usda.gov, Washington, DC ■ CentroNia; www.centronia.org, Washington, DC ■ City Blossoms; www.cityblossoms.org, Washington, DC ■ Let’s Move Campaign; www.letsmove.gov, Washington, DC ■ City Growers; www.citygrowers.org, Long Island City, NY ■ Nourishing NYC; www.nourishingnyc.org, New York, NY ■ Just Food; www.justfood.org, New York, NY ■ Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Homeless Health Initiative; Philadelphia, PA ■ Garden on the Go; Indianapolis, IN ■ Sesame Street, Growing Hope Against Hunger; New York, NY.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Homeless and Foster Youth Find their Voices

by Diana Scholl

More and more homeless youth and those in the child welfare system are advocating legislatures and governments on behalf of their own needs, and a growing number of groups and coalitions are assisting them in their efforts.

The benefits of giving young people seats at the table are manifold. Youth are empowered and emboldened by the experience, and as a result, policies are put in place that reflect the real needs of people most affected by homelessness and foster care.

One of the many ways homeless and foster youth have been advocating for themselves is by testifying at congressional briefings and caucuses, such as the recent hearing about changing the definition of homelessness (above) and the Senate Caucus on Foster Care (below).

Destiny Raynor, 15, testified before the U.S. House of Representatives Financial Services Committee in December 2011 about changing the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s definition of homelessness to better encompass families who are not living in homeless shelters but do not have stable homes—such as those doubled up or living in motels or cars.

“There are some programs that provide housing help, but we don’t qualify because my dad doesn’t have a regular job and he doesn’t make enough money. When Beth [the school homeless liaison] pays for the motel room, we are considered homeless,” Destiny testified before Congress. “When my dad pays for the motel room, we are not considered homeless. That doesn’t make sense to me. It’s the same hotel room, and it’s hard to live there when you are young, no matter who pays.”

While many advocates and experts testified before Congress, those in attendance said the most compelling testimonies came from current and former youth, like Destiny, who spoke about their experiences being homeless. The bill, HR 37, is currently making its way though the House of Representatives.

“I was meeting with [Congress] members’ staff recently, and they are still talking about the kids’ testimonies,” says Barbara Duffield, executive director of the National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth, which is advocating in favor of the bill. “It’s one thing to look at the issue from a 30,000-feet perspective. It’s another to be able to say, ‘Brittany herself said she felt safer in her car.’”

Duffield says that to make sure the youth felt comfortable on the big day, they practiced their testimony beforehand and met one another the night before they testified in order to increase their comfort levels.

Duffield says she understands why there is reluctance to include youth in advocacy.

“The instinct of most people, including educators and providers, is not to traumatize people. Some students you wouldn’t ask, but for some, it’s part of the healing process,” Duffield says.

For Destiny, the experience was life-changing, and she wants now to pursue a career as a child advocacy lawyer. And although her family currently has permanent housing, she was happy to help homeless teenagers who came after her.

“If you’re a greedy person, when you need help no one’s going to help you,” she says. “I would tell anyone else interested in doing this that they should, and that if they’re nervous, it will wear off.”

Seats at the table

There have been countless local, state, and national victories as a result of youth advocacy involvement and agenda-setting. Fostering Connections, the national legislation that permits states to allow youth to remain in foster care up to age 21, was the result of youth setting the agenda.

Advocacy group California Youth Connection has had a legislative victory every year since its founding in 1988. Its first major (and teen-friendly) victory: allowing foster youth to get driver’s licenses. In Oregon, youth were instrumental in passing a bill that provides free college tuition for all youth who have been through the foster care system.

Youth from The Mockingbird Society, including David Buck, took to the streets during a march on Seattle’s Youth Advocacy Day to ensure that their voices were heard.

Angela Lariviere spent most of her childhood homeless or in transitional housing, and founded the Youth Empowerment Program at the Coalition on Homelessness and Housing in Ohio after realizing that middle-class youth were asked to volunteer and engage in their communities, but the same wasn’t expected of homeless young people. Now, more than 250 homeless and foster youth per year participate in community service and advocacy that her organization facilitates.

“A big thing is we do a lot of community service. We tell them, you may not have a stable address, but you are part of your community,” she says.

Lariviere says her first priority is “just getting youth at the table.”

“When people say they want youth at the table, it doesn’t mean they’ll listen to what they have to say,” she says. “Working with youth means really valuing them as experts, but also valuing adult partners.”

Janet Knipe, executive director of the National Foster Youth Action Network (NFYAN), says that for youth advocacy to work best, adults have to learn take a step back, and let youth take the lead.

“One of the biggest challenges is getting community partners and stakeholders to be open to working with youth,” Knipe says. “Adults often want to make decisions quickly, and jump in to solve problems. It’s hard for all of us adults to give up that control. But we have to think: How can we truly empower and engage youth in a meaningful way?”

NFYAN, a national spin-off of the California Youth Connection, has organizers across the country who themselves were in foster care.

With 15 years in the child welfare system under her belt, Sophia Herman saw firsthand the barriers of being in foster care. She was frustrated by being separated from her siblings, and was particularly upset when her sister’s psychiatric medication regimen was changed depending on her foster care placement.

Above top: Talking with the media can be an empowering advocacy tool for youth.

Above bottom: After testifying at a congressional hearing, a group of students were invited to have lunch with Congresswoman Judy Biggert (R-IL).

But as a youth bouncing from placement to placement in California, Herman, now 25, felt like no one was listening to what she wanted. “Other people are making decisions for you, and a lot of times they don’t take a step back to see what’s available to you,” Herman says. “Foster youth aren’t able to do the same things other kids can because of liability. I wanted to just do typical social things teens and young people do. No one ever tried to make my life normal.”

But Herman joined up with the California Youth Connection, and worked to advocate on behalf of foster youth in California. Through that work, she was hired by NFYAN, where she works to organize youth in Mississippi.

“I think the Action Network is a great organization for the validation of youth voices, to allow young people to be heard in a professional manner,” she says. “The squeaky wheel gets the oil, and we’re teaching youth how to use that to their advantage instead of being scared of professional social workers.”

Youth can often speak from a position of experience. David Buck, now 22, ran away from a group home in Idaho at age 17, and spent three years homeless in Seattle and San Francisco. “It was awful. The [worst] thing about foster care is when you’re put in a placement, and you’re constantly bombarded with the fact that your parents aren’t around. I felt like I was essentially a prisoner in the group home. I figured running away would give me an opportunity to take life into my own hands,” he says.

Buck connected with The Mockingbird Society, a Washington State-based group that advocates for youth in homeless and foster care. Every year, The Mockingbird Society sends 250 people with experience as homeless youth or in the foster care system for Youth Advocacy Day, back-to-back meetings with legislators to advance the agenda youth themselves created. The Mockingbird Society’s legislative achievements have included a bill that extends health care benefits to youth exiting foster care until they are 21 years old, and 2011’s Extended Foster Care bill, Washington’s first step toward implementing Fostering Connections, allowing youth finishing their secondary education to remain in care until age 21.

One accomplishment came in 2009, when The Mockingbird Society worked to amend legislation that notified authorities within eight hours if a youth entered a drop-in center. “It sounds good on paper, but I used to go to a lot of drop-in centers in Seattle, and I can think of two individuals I know who were informed by staff that if they write down their names they would be reported. That spooked them. They were running away because of abuse or something. When they’re told that cops will get involved, they leave.” Buck worked to educate legislators, and the bill was changed so that in some circumstances, drop-in centers have up to 72 hours before notifying authorities, to give drop-in centers time to better assess the needs of the youth who seek help.

“I feel like advocacy is part of my duty as someone who has experienced these things and is in a position to do something about it,” Buck says.

Resources

National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth; www.naehcy.org, Washington, DC ■ California Youth Connection; www.calyouthconn.org, San Francisco, CA ■ Coalition on Homelessness and Housing in Ohio; www.cohhio.org, Columbus, OH ■ National Foster Youth Action Network; www.fosteryouthaction.org, San Francisco, CA ■ The Mockingbird Society; www.mockingbirdsociety.org, Seattle, WA.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Financing the Future:

The Growth of Financial Literacy for Students of All Ages

by Stephen Santulli

Steve Burman arrives early.

His weekly financial literacy course for parents at a Bronx homeless shelter is going to start in a few minutes. He places brochures announcing this week’s topic, payroll and income taxes, face-up in front of each chair at the table. He prepares for a full house.

In his fourth round of workshops at the shelter, Burman understands that today’s lesson may have 5, or 25, attendees. This is a shelter for homeless families, and residents have a lot on their plates—meetings with caseworkers, young children to care for, the ongoing struggle to find employment—all before they can consider supplementing their education at Burman’s seminars.

Instructor Laurel Kubin of Make Change NOCO teaches financial literacy to adults who are at risk of being evicted from their homes, so they can better manage their money and remain stably housed with their families.

He understands what he is up against. He knows the shelter residents’ time is valuable. Sometimes he provides additional incentives, such as donuts and fresh coffee, to help boost attendance. Over the PA system, the voice of a shelter staff member promoting the workshop drifts into the children’s nursery that is Burman’s classroom. And he waits for the sound of footsteps climbing the stairs. In about five minutes, Burman will dive into the day’s lesson plan, adapted from the literature of the credit-counseling agency he founded, Credit Advocates Counseling Corp (CACC).

Educators, researchers, and specialists in financial literacy all say that the demand for this type of instruction has grown since the Great Recession. But some experts want to shift the focus of the programming away from credit-counseling services like debt management and bankruptcy preparation, which serve clients after their finances have fallen into disrepair, to a preventative approach, teaching the basic principles of sound money management in the hope that low-income people can avoid running into financial trouble in the future.

Financial literacy education casts a wide net, ranging from the more complex details of managing personal finances, like building credit, repaying debt, and making wise consumer decisions, to more basic knowledge about budgeting and banking, and even elementary skills like goal-setting. Professionals teaching financial literacy have developed age-appropriate lesson plans for students at all stages of life.

The economic downturn revealed a greater need for those skills in the broader population, educators say, particularly given the role of consumer debt in precipitating the financial crisis. But it’s also made it less likely that traditional credit-counseling services can provide the lifeline they once did to Americans facing financial hardship.

Dave Jones, the president of the Association of Independent Consumer Credit Counseling Agencies (AICCCA), says that many of those hit hardest by the downturn may be in too deep a financial hole for credit counseling to help. The AICCCA represents over 170 credit-counseling agencies nationwide, including Burman’s CACC. Jones says his members counsel roughly 4 million people a year, and that before the recession, roughly 20% of clients who approached credit counselors were among those eligible for assistance through debt-repayment plans—those who could still see light at the end of the tunnel. Today, he says, AICCCA members assist only around 9% of clients with debt repayment.

“The biggest challenge that we face today is that we can’t get to people soon enough,” Scott says.

With even middle-income Americans facing mounting debts, educators see a greater urgency for reaching low-income clients with a basic financial literacy education. The challenge they face is how to make this type of education resonate with clients who are poor or homeless, and may face more immediate financial difficulty.

Parents who are experiencing homelessness learn how to better budget and manage their finances through financial literacy classes taught by Steve Burman, founder of Credit Advocates Counseling Corp., at a shelter in New York City.

In New York City, Mayor Michael Bloomberg took a step toward meeting that challenge by creating a new Office of Financial Empowerment within the Department of Consumer Affairs in December 2006. The office, which the City describes as the first of its kind in the country, provides consumer education, credit counseling, and financial literacy education, all aimed specifically at low-income clients.

The New York City model has received national attention. At the Center for Financial Security (CFS) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Faculty Director J. Michael Collins says that financial literacy education is most effective when integrated into existing services for low-income individuals, such as public assistance programs and transitional housing. Collins says that these programs catch clients in moments of transition, an optimal time to emphasize what he calls “teachable moments” for clients.

Research conducted by the center suggests that an integrated approach to educating low-income clients, bringing together public and private resources, yields promising results. Between 2009 and 2011, CFS conducted surveys of families around Wisconsin who participated in a financial literacy program integrated into Head Start, the education and health care program for low-income children. The program included regular newsletters, workshops, and coaching. The survey found that families participating in the programs reported modest increases in confidence when it came to certain financial tasks and the ability to meet their financial goals.

Service providers working with low-income and homeless individuals are putting this approach into practice in communities across the country.

The Homelessness Prevention Initiative (HPI) in Fort Collins, Colo., serves low-income families in immediate danger of losing their housing by providing rental assistance to prevent eviction. The assistance used to last only one year, but HPI has extended it since the start of the downturn, according to Executive Director Sue Beck-Ferkiss.

The initiative also offers interested clients an option called Education Extra. Participants commit to a two-stage financial literacy program, starting with a two-hour group seminar and followed by one-on-one counseling, during which clients develop individualized spending plans. HPI partners with Make Change NOCO, a local credit-counseling service, to run the classes. Last year, 269 individuals from 123 households took part, Beck-Ferkiss says.

Even though the clients that HPI serves are on the verge of eviction, Beck-Ferkiss says that the focus on long-term financial skills is productive. “The skill-building has to start somewhere,” she says.

In the South Bronx, the family shelter where Burman runs his workshops serves a population in even greater distress. Staff at the shelter initiated the partnership with Burman and CACC after residents requested more adult-education programming. The shelter’s model integrates a range of supportive services into transitional housing, so Burman’s lessons blend seamlessly into the existing programming structure for residents.

The eight-week financial literacy classes at a Bronx-based family homeless shelter provide parents with an opportunity to discuss real-life money issues.

That doesn’t mean that attending classes and absorbing the information is always easy. On a Wednesday in early February, Burman launches into his lesson in his usual fashion, leading students in a group read of the week’s brochure, “Developing Banking Relationships.” Going around the table, the six students, all women, work through the pamphlet a few paragraphs at a time, occasionally raising their voices to be heard over the cries of the three young boys who have come to the nursery with their mothers.

Afterward, Burman builds on the written material with a free-flowing lecture fleshing out the material in greater detail. Leaping from one topic to the next, he impresses on the students a few nuggets of financial wisdom that may come in handy down the road. Banks are insured, but safety-deposit boxes are not. Pay off only the minimum required on your credit card balance each month, and you’ll eventually owe more in interest than your entire balance. He even gives a short overview of how to set up an Individual Retirement Account.

But financial literacy education really begins with the basics, to lay the foundation for better decision-making down the road. Other handouts outline some basic principles: “How do the decisions I make today impact me tomorrow?” They describe the concept of an opportunity cost—“what you pass up when making a decision”—and encourage students to mentally divide future purchases into “needs” and “wants.”

Now Burman and his students pass into the next phase of the lesson: the roundtable discussion. Burman wonders aloud how recent changes to New York City’s rental-assistance programs affect decision-making, and his students respond knowingly. They’ve all been grappling with these changes. Housing support, which used to provide reliable vouchers, switched to require proof of income, which most of the women present are unable to provide.

On one side of the table, a woman explains how the lesson applied to her own life. Her iPhone was recently stolen, she says, presenting her with a choice. Should she buy another iPhone, or buy a smaller phone to save money? A cell phone is a need, but given the variety of choices, at what point does it become a want?

After the lesson, the woman considers what she’s just heard. At 45, Zareth has to support two sons, ages 6 and 16. Unable to work due to a disability, she has been receiving unemployment, and has other debts to account for, including unpaid student loans. This is the second financial-literacy class she’s come to since entering the shelter six months ago. She says that the opportunity to hear from others in similar circumstances is the most valuable thing about the workshop, and she appreciates Burman’s dedication.

“You learn information, and you tell your story, so that you can get even more information,” she says.

Contemplating if his lessons have gotten through at the shelter, Burman is circumspect. The mission here is different from the one with which he started CACC in 1992. Most of CACC’s clients face acute financial hardship resulting from a few poor decisions—towering credit card debt, for example. The shelter population, of course, faces more intractable difficulties, often compounded over years, or even generations, of bad circumstances.

“It’s a tough crowd to reach,” he says. “Most of these people are there because it’s almost the last stop on the train.”

Still, he thinks he’s had a positive impact overall. This is the fourth round of seminars he’s run there, using the same eight-session program he developed from CACC’s broader curriculum. Financial literacy is a hot topic lately, he says, especially because of the public perception that irresponsible financial behavior played a leading role in the run-up to the financial crisis that caused the downturn.

While Collins sees great potential for merging financial literacy education into existing services for low-income individuals, he is more skeptical that the traditional curriculum can reach the homeless, who frequently experience immediate crises that may need to be addressed before laying the foundation for better financial management down the road.

“The struggle is knowing when is safe enough and secure enough to start looking at these higher-order needs,” he says.

But the distinction between middle- and low-income clients may be less significant now, since the recession pushed many formerly well-off families into a lower standard of living. Becky House counsels clients in severe situations. Her Seattle-based credit-counseling firm, American Financial Solutions, runs workshops for people who are in transitional housing or trying to get into transitional housing. She’s noticed a change in the population looking for housing. Increasingly, she sees young families who never expected to be homeless, but were forced from their homes after an unexpected event like job loss, divorce, or separation.

Classes are set up to encourage homeless parents to join in, allowing young children to accompany their parents, and sometimes providing incentives such as free diapers.

Her program rebuilds those families’ hopes from t

he ground up. Discussion starts with basic questions, like “Why do you want to own a home?” and proceeds to understanding how building credit can be an asset, not merely a way of sinking into debt. The goal is to move people back to permanent housing, and offers an incentive program to match funds that participants save up to $700.

Those same lessons resonate at the shelter that CACC serves. Burman says that his students have changed his perception of homelessness. Stories like Zareth’s reveal that homeless adults living in shelter still have living expenses, and therefore a basis for future financial planning. The CFS report on families enrolled in Head Start, meanwhile, found that 90% of those surveyed had completed high school, and 48% had completed some college.

Only time will tell if the increased focus on financial literacy yields long-term success. One unresolved question is what type of educational programming is most successful. In New York, the new Office of Financial Empowerment is conducting a survey jointly with CFS to evaluate the impact of its programming on low-income clients. In particular, the survey aims to determine whether group education programs, like Burman’s, or individualized counseling is more likely to influence financial behavior. Preliminary data collected over 2009 and 2010 indicates that one-on-one assistance resulted in better indicators of financial security for clients, such as reduced debt levels and higher credit scores, but the study is still in progress.

Inadequate financial knowledge among low-income families also affects children, since they cannot learn these lessons from their parents. That has led to a greater emphasis on the need for finacial-literacy education in schools. Only four states—Missouri, Tennessee, Utah, and Virginia—require that students complete a semester of financial literacy work to graduate, though many other states offer some instruction on this topic.

Every two years the Jump$tart Coalition for Personal Financial Literacy, which develops curricula for teaching financial management used by 150 organizations across the nation, conducts a survey of students’ financial knowledge. Survey results in 2008, the most recent year in which data was collected, found that students from low-income backgrounds performed significantly worse in the evaluation, across all categories.

“These are the families that are least prepared to instruct their own kids,” says Laura Levine, the executive director of Jump$tart.

Even though students need to reach middle or high school to understand the more complex aspects of financial management, Levine says schools need to start early in teaching students lessons about personal finance—so they won’t be making up lost ground as adults.

Resources

Credit Advocates Counseling Corp.; www.creditadvocates.org, New York, NY ■ Association of Independent Consumer Credit Counseling Agencies; www.aiccca.org, Fairfax, VA ■ New York City Department of Consumer Affairs, Office of Financial Empowerment; www.nyc.gov/ofe, New York, NY ■ Center for Financial Security; www.cfs.wisc.edu, Madison, WI ■ The Homelessness Prevention Initiative; www.homelessnessprevention.net, Fort Collins, CO ■ American Financial Solutions; www.myfinancialgoals.org, Bremerton, WA ■ Jump$tart Coalition; www.jumpstart.org, Washington, DC.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The Historical Perspective—

Exhibiting Poverty

by Ethan G. Sribnick and Sara Johnsen

In 1900 New York was both the richest and second-most populous city on Earth. But beneath its veneer of prosperity, many of its 3.4 million residents were struggling to get by, often forced to live in crowded and unsanitary tenements. Tenements were typically 25 feet wide by 100 feet deep and six stories tall, built to accommodate 26 families in 325-square-foot apartments. Then, as now, high rates of poverty in New York City accompanied high demand for housing, and families often had to double up or take in boarders to pay the rent, creating dangerously overcrowded conditions. By 1890 the Tenth Ward of Manhattan’s Lower East Side was home to more people per acre than anywhere else on the planet. In the densest tenement districts, developers built housing on almost every lot, leaving no room for parks or other open spaces. Rear tenements were often built in the yards behind street-facing tenement houses, allowing just enough space in between for shared toilets. Moreover, street-facing tenement houses were built right against one another, leaving only small air vents that often became receptacles for trash. Poor air quality, lack of sufficient space and light, lack of plumbing and fresh water, and other defects bred sickness, particularly tuberculosis. While cramped housing conditions existed in cities across the country, poor New Yorkers paid more for their atrocious accommodations than their counterparts in other cities.

This photo, one of a series taken by Lewis Hine in 1908, documents conditions in one of the most crowded residential districts in the world. Here, children play in trash-strewn Orchard Street. Photo courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Generations of reformers had attempted to improve living conditions for poor and working-class residents of New York, with little success. The housing regulations passed during the 1800s—along with lax enforcement of the laws—had done little to curb the incentive of developers to build as much housing as they could in as little space as possible. By the 1890s, reformers had realized that the tenement problem could be solved only with government help.

In 1898 a young social worker named Lawrence Veiller persuaded the Charity Organization Society, New York’s leading philanthropy, to form a Tenement House Committee to conduct research and propose improvements to New York City housing. The committee carefully documented the horrific conditions of much of the housing in New York, as well as the concentration of poverty and disease that plagued tenement districts. Veiller argued that the conditions of life among the lower classes created “sick, helpless people … and a host of paupers and charity seekers.” He believed that unsafe, unsanitary, and crowded living conditions exacerbated poverty. If housing were improved, the poor would be healthier and better able to contribute to the community.

For Veiller and other reformers, the need for stricter housing regulations and better enforcement was obvious; the difficulty lay in implementing new policy in the face of opposition from the city’s powerful building interests. Veiller came up with a brilliant public-relations move: He would display the data the committee had collected in a public exhibition for all to see. Such a barrage of carefully curated information would overwhelmingly demonstrate the extent of the housing problem in New York City and force the city to accept reform.

Poor families lived in crowded and unsafe housing. Here, a family sits in their narrow, windowless living room.

The Tenement House Exhibition opened on February 1, 1900; by the time it closed, two weeks later, it had attracted more than 10,000 visitors. The exhibition traveled to other American cities before being displayed at the 1900 World’s Fair, in Paris. Visitors viewed more than 1,000 photographs depicting environmental conditions that perpetuated poverty: severely overcrowded bedrooms, dangerous stairs, inadequate fire escapes, and narrow airshafts. The exhibit also included charts, diagrams, and tables detailing the state of health, nationality, and average age of tenement inhabitants.

Two series of maps were particularly revealing. A series of “poverty maps” reproduced the blocks of tenements in the city, demarcating each building. Black dots covered much of the map; each dot on a building represented five families who had applied for charity from that address in the past five years. Similarly, “disease maps” used a dot on a building to note each case of tuberculosis discovered there in the past five years; again, at least one dot was found on nearly every tenement house, and the worst buildings had up to 12 dots each.

This photo by Jessie Tarbox Beals depicts a typical tenement kitchen and bedroom. The window in the bedroom probably provided air and light for the entire apartment.

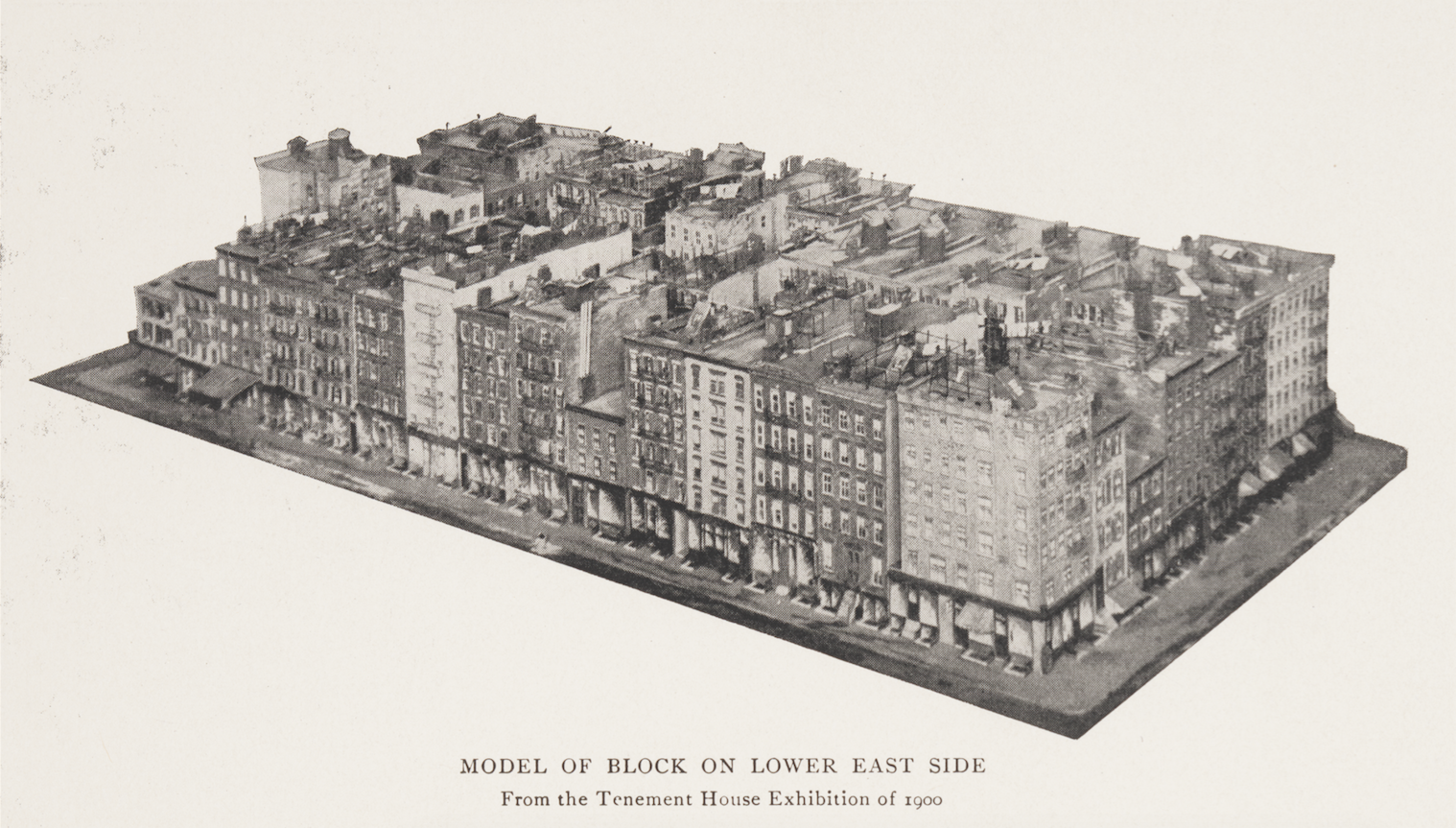

The crowning achievement of the exhibit, however, was a cardboard model of an actual tenement block. The exhibit showed dramatically what these 39 tenement buildings, located at Chrystie and Canal streets on the Lower East Side, actually looked like. It noted that the whole block, which was home to 2,781 people, shared 264 water closets, and that residents in only 40 apartments were lucky enough to have hot running water. There was no stationary bathtub in the whole block. Thirty-two recorded cases of tuberculosis on the block attested to the prevalence of disease, while the 660 applications for charitable assistance attested to the depth of poverty.

The exhibition drew media attention and elicited a quick response. In his opening speech, Governor Theodore Roosevelt called for minimum housing standards to “cut at the root of the diseases which eat at the body social and the body politic.” Roosevelt’s support eventually resulted in the passage of the Tenement House Act of 1901. This law created a building code requiring improvements in existing tenement buildings: Landlords had to replace old-style outhouses with more modern water closets, install windows connecting interior rooms to adjoining exterior rooms to improve ventilation, provide fire escapes, and add windows to illuminate previously pitch-black hallways. The law also specified that future tenements had to include center courtyards and a private water closet in each apartment.

This model, a highlight of the Tenement House Exhibition, shows a Lower East Side block that was home to nearly 2,800 people living in 39 six-story tenement buildings. Exhibition organizers argued that basic government regulations could improve conditions on blocks like these and ameliorate the rampant disease and poverty found there.

Equally important was the creation of the New York City Tenement House Department to enforce the 1901 law. This department consolidated powers previously spread across various city departments claiming the authority to approve new building plans, inspect completed buildings, and maintain records on all existing tenements in the city. Veiller believed that this new department would finally provide what housing reform in New York City had long lacked: enforcement. The housing conditions that had horrified residents and observers of New York’s slums for decades would finally come under more effective supervision.

In the early 1900s Veiller and other reformers believed that research could transform public policy. From housing to education to public health, they successfully documented conditions and persuaded the government to generate improvements. The Tenement House Act of 1901 was only one step in a continuing effort to create adequate and affordable housing. Today, families in cities across the United States still confront decrepit and unsafe dwellings and overcrowding as they struggle to find places to live. When Lawrence Veiller gathered data and presented it to the public through the Tenement House Exhibition, he established a model for future campaigns. From grassroots activists to research institutes to think tanks, advocates today understand the importance of documenting social conditions and, even more crucially, of using social documentation to raise public interest. This strategy can still succeed in changing public policy and improving housing conditions for America’s struggling families.

Photos courtesy of the Community Service Society and Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Resources

DeForest, R. and Veiller, L. 1900. The Tenement House Problem: Including the Report of the New York State Tenement House Commission of 1900. New York: Macmillan Company. ■ Lubove, R. 1962. The Progressive and the Slums: Tenement House Reform in New York City, 1890–1917. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ■ Jackson, A. 1976. A Place Called Home: A History of Low-Cost Housing in Manhattan. Cambridge: MIT Press. ■ Jackson and Dunbar. 2002. Empire City: New York through the Centuries. New York: Columbia University Press.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Guest Voices—

Why I’m Documenting Family Homelessness in the United States, Mile After Mile

by Diane Nilan

My solo journey to chronicle invisible homelessness among families and youth commenced in November 2005, me behind the unfamiliar wheel of the 27’ rig that the bank and I now own. Confident that homeless kids would not be scarce beyond the Chicago metro area and that I’d be able to depict their plight and promise, I aimed this lumbering vehicle—my home since unloading my townhouse for this house-on-wheels—down this nation’s backroads, ready to point video and still cameras at people and sights before me.

Before this horrific post-economic-meltdown, things were bad, but the dire sights unfolding before me shocked me. Melding my housing inspector, shelter director, and poverty advocate’s mind and eye, I witnessed an obvious erosion of people’s quality of life in nonurban areas. Pathetic housing stock, empty storefronts, overcapacity shelters, and shredded safety nets signaled the devastation that this denial-prone nation was ignoring. Stories from kids and parents, east coast to west, confirmed the undocumented depth of homelessness while illuminating courageous resilience.

Disasters aplenty, from the far-reaching destruction wreaked by Katrina to the subtle empty chairs in the local barber shop of a job-challenged community, the web of poverty covers this nation like kudzu, threatening to choke the life out of a once-proud country that took care of its own. Mother Nature, unscrupulous scammers, human nature, and hard times crumpled millions like empty beer cans, discarded along the roadside as trash.

Gallant efforts to repair, rebuild, and restore lives compete with Wall Street robber barons and deficit-distracted legislative priorities. Communities patch together sparse provisions of food and shelter. Schools stretch their purpose to include providing food, clothing and hygiene supports. Parents shrewdly weave resources out of seemingly nothing to keep a roof over their families’ heads. Youth scrape together essentials for survival, adapting to deficiency.

All the while, media’s stereotypes further confuse elected officials charged with ensuring the well-being of constituents. Congressional reports all but ignore the burgeoning numbers of homeless families and youth, concentrating on the adults accused of sullying the imagined pristine streets of has-been cities and towns. HUD’s war of words excludes the bulk of this nation’s un-housed population.

Compassion competes against cold-hearted budget cuts. The pattern of ignoring human infrastructure rises to new heights, taking down the most vulnerable into a vortex of desperation. Yet, like the pocked roadways connecting one small town with another, the thread of kindness connects human-to-human, sharing vital essentials of food, shelter and hope. I step out into a new place, filled with wonder at the stories of fortitude and goodwill.

Nilan gets ready for another leg of her cross-country journey in “Tillie,” the road weary motor home in which she has clocked 130,000 miles across 48 states since she began, in 2005.

Madison, FL: Mid-December in northern Florida can get cold. But that’s too bad for people in homeless situations unless it’s really cold, usually below freezing. Only then do sparsely located emergency overnight shelters open. I can’t imagine what it’s like when it’s a degree or two above the opening standard.

Reno, NV: Driving down one of the seedier streets of this city, I spotted this motel and kids playing in the parking lot and in the open hallways. Knowing that families often turn to motels as an escape from life on the streets (at the time in 2009, Reno had no family shelter), I pondered life as a child using motel railings as playground equipment.

Fairmount, GA: On a dreary day in March 2010, I ventured onto the backroads of northwest Georgia, an area devastated by the housing industry’s demise because this is the home of carpet manufacturing. The closed tiny food bank beckoned, causing me to wonder about their food supplies in this time of economic turmoil. The rest of the town looked like it would be in need of a bailout. Probably not going to happen …

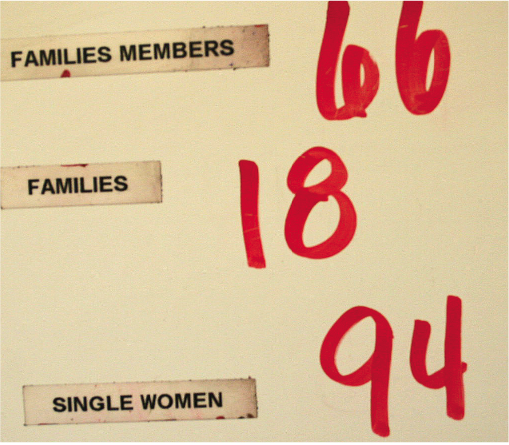

Phoenix, AZ: During the process of filming our documentary, on the edge, director Laura Vazquez and I visited the Watkins Overflow Shelter in a warehouse provided to United Methodist Outreach Ministries (UMOM) by the City of Phoenix. Because of my background as a former shelter director, this sign spoke to me, and I shuddered at the scope of homelessness among families and women in this city.

Lafayette, LA: Curiosity got the best of me so I moseyed over and began chatting. Sure enough, this woman and her son were homeless, vulnerably doubled-up with someone who didn’t want them staying there. So mom and her seven-year-old visited this park to do laundry, shower, and have a cookout. She lacked the equipment to cook their hot dogs, so I provided tongs, paper plates, and encouragement.

Phoenix, AZ: Watkins Overflow Shelter. I was struck by the industrial nature of efforts to house homeless families. I suppose on one hand, it’s better than the lack of alternatives these dozens of families would have had to cope with if Watkins was not an option. That is a sad statement of our nation’s disregard for the well-being of families.

DeKalb, IL: Hope Haven shelter provides a sanctuary in this college town about 75 miles west of Chicago. This pleasant, affable mother agreed to let me photograph her baby soon to be born, another infant whose life will begin in a shelter.

Hingham, MA: Wompatuck State Park. I noticed the composition of the clothes hanging on the line didn’t fit the typical array. It looked more like someone washed out items in a five-gallon bucket. Speaking with the mother verified my guess: She, her husband and their 18-month-old baby were having, as she put it, “hard times.” They also didn’t have money for propane to heat their little rig. The temperature got down to the 30s at night. I heard them arguing—the well-worn script of the desperate income-challenged (albeit mobile) households—so I shared an “extra” electric heater with her.

Resources

HEAR US, Inc.; www.hearus.us Naperville, IL.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Starting the Conversation: 2012 ICPH Conference a Success

In January, the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness held its national conference, “Beyond Housing: A National Conversation on Child Homelessness and Poverty,” at the Millennium Broadway Hotel in New York. The conference took place from Thursday, January 19 to Friday, January 20, and featured a variety of speakers, panel sessions, and other events. Approximately 450 policy makers, educators, service providers, and other stakeholders attended the conference.

Seth Diamond, commissioner of the New York City Department of Homeless Services, gave welcoming remarks and discussed the importance of research.

The conference opened with a keynote address by Ralph da Costa Nunez, president and chief executive officer of the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness. Dr. Nunez filled in for author Jonathan Kozol, who became ill and was unable to attend. The keynote address covered the relationship between homelessness and poverty, with Dr. Nunez offering an historical perspective on government’s role in regulating poverty, focusing on policy changes in New York City. He also called for a specific solution to poverty and homelessness in America. A video of his keynote address can be found at www.ICPHusa.org.

“The answer of where to begin to reduce homelessness in America is the shelter,” Dr. Nunez said in his keynote address. “But it shouldn’t be called a shelter, it should be called a community resource center.”

According to Dr. Nunez, homeless shelters in the United States could offer comprehensive services for homeless families including education, training for employment, after-school programs, and day care. He also announced ICPH’s soon-to-be-released plan, “A New Path: An Immediate Plan to Reduce Family Homelessness,” which can be found on the organization’s Web site.

Below, from left: 1. and 2. Meals at the conference also served as a time for participants to connect with other professionals. Attendees engaged in roundtable discussions, conversing about various topics relating to homelessness and poverty, and sharing experiences from across the country. 3. The keynote address on Thursday was preceded by a skit performed by the City University of New York’s Creative Arts Team, which depicted a fictional homeless family. The actors also led a short question-and-answer session. 4. ICPH hosted 20 panels over the course of the conference, including this one on “The State of Permanent Housing.”

Lunch on Thursday afternoon was another productive aspect of ICPH’s 2012 conference, as members of the organization’s staff and other experts were placed at different tables to lead discussions on their particular areas of expertise. On Thursday evening, ICPH held a screening of the documentary on the edge, produced by HEAR US Inc. President Diane Nilan. The film depicted the experiences of seven women living in suburban towns, rural areas, and resort communities across the United States, who shared their personal experiences with homelessness.

Panel sessions were held throughout the conference and focused on a wide variety of issues relating to family poverty and homelessness. Attendees were able to choose from among 20 topical discussions, such as “The Power of Data in Public Policy,” “The Dollars and Sense of Federal Funding,” “The Changing Face of Today’s Homeless Veterans,” “Media as a Tool for Advocacy and Awareness,” and “The Effect of Foreclosures on Educational Outcomes.” Conference guests were also able to visit New York City sites including the Children’s Museum of Manhattan, to see its program for young homeless mothers and children, a family shelter, a supportive housing site, and a comprehensive community-based prevention center.

Aurora Zepeda, executive vice president of ICPH’s sister organization, Homes for the Homeless, closed the conference on Friday afternoon with a brief address, before opening the microphone up for comments from the audience. Conference attendees described their own work with homeless families, or related policy work, and also spoke of their experiences from the conference. Below are excerpts from interviews conducted throughout the conference:

Sarah Fujiwara (Horizons for Homeless Children, Roxbury, MA): I’ve come [to the conference] for a couple of reasons. I’ve known the work of the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness for a long time and really appreciate the perspective they bring and the research that they do. So I was certainly interested in participating and also networking and learning from other providers from around the country. I have heard Ralph Nunez speak before, but it’s just a very helpful perspective for me to hear his historical view. It helps us to not get stuck in the moment so much, but to really understand there are cycles; cycles of hope, as well as cycles of disturbing information.

The [panels] I’m interested in … are foreclosure leading to homelessness, which I know impacts some of our families. We serve 175 children each day in three community children centers and then we work with a shelter network of about 145 shelters across the state and have programs for those children. I know that a portion of the causes of homelessness is foreclosure, but I don’t know that much about it.

Patricia Popp (Project HOPE – Virginia, Education for Homeless Children and Youth, Williamsburg, VA): I really have a passion for making sure our children who are highly mobile are appropriately served. This was an opportunity to share some of the things we’re doing in Virginia and across the country, and to learn from the other folks about what’s going on in other parts of the country. I presented at the “Early Childhood Education” panel and I’ll be doing a session tomorrow on effective teachers who work with highly mobile students. All that mobility really does have an impact on a student’s ability to feel comfortable in a classroom and learn. The more we can do to keep them stable, and help teachers understand how to make them feel welcome and belonging in the classroom, makes a difference in how they’re able to achieve in the long run.

We know these children do succeed and go on to college. What’s really exciting is I’ve been in the field for 16 years. We spent so much time making sure children were getting into our public schools, and now we’re beginning to look at whether they’re getting into higher education. We wouldn’t be asking that question unless we really started to make a difference with our children who are school-aged, so it’s exciting to see things evolve.

Barbara Peters (First Step Staffing, Atlanta, GA): I came down to talk about employment and ways to get folks back into the workforce, and to learn more about what other people are doing in the world of employment but also in the world of mainstream benefits for homeless families. The conference has been great; I’ve gotten a lot of information on that. Folks who are homeless have particular barriers around employment and they really are difficult to address, and sometimes it’s as simple as having a place to contact them. So agencies really have to collaborate and work together to get folks back into the work force. Re-entry is tough, especially in this economy.

Arsenio Gonzalez (Ruth Fernandez Family Residence, Bronx, NY): Now and again it’s good to get some new ideas. The workshop was excellent, and I got some information that I’d like to take back to my staff. I went to the “Preventing Homelessness” panel, where they presented a program to help prevent homelessness. In the Bronx housing court they deal with people who are about to be evicted and give them financial assistance and social services; I think it’s a great idea. The other workshop I attended today was on trauma-informed treatment, which was excellent. I had no idea that kind of stuff existed, so I’m definitely going to follow up on a resource to see if one of them will come down and do some staff training.

Joyce Lavery (Safe Haven Family Shelter, Nashville, TN): I’ve come to this conference because unlike New York City and New York State, our homeless system isn’t very coordinated. It’s very hard to learn about the system, or to learn about best practices and what works in other communities. I’m very much a best practice research-oriented person and it’s very important to me, especially where I live, where it’s so hard to get information about other like-minded shelters and homeless systems. I want to get a handle on the issues, to hear the messages and hopefully bring them back to my organization and my community so we can be more effective in what we do. It’s really about being effective, about learning, and about enriching my practice.

Margaret Lovejoy (The Family Place, St. Paul, MN): I came here to the conference to hear what other people are saying and doing about the issues of homelessness, so that together as a nation, as a community, and as a person we can work toward getting a handle on homelessness so people can go in and out of homelessness at a quicker rate. Right now in Minnesota, in Ramsey County, they’re stalled in homelessness, and that’s not a good place for families to be. As our speaker yesterday also mentioned, the issue isn’t homelessness; the issue is poverty. Today I went to the media session. They gave us good tips on how to stay in relationship with the media in your area, which is very important. Yesterday I visited a family resource center in Brooklyn and got ideas about how to work better on the issue of poverty and stabilizing families.

Luke Nasta (Camelot Counseling Services, Staten Island, NY): I moderated the “Substance Abuse” panel session, which had four panelists from California…who provide multiple services, including substance abuse services, for families in California, ranging from underage children to adults. They help with all the different problems that come along with youth who are disenfranchised, who are on the street, have no trusting relationships with adults, or are maybe the victims of abuse and neglect. They come to their program seeking housing and they do a fantastic job addressing all their needs.

ICPH President and CEO Ralph da Costa Nunez commented on the success of “Beyond Housing,” and said attendees were able to learn about many different issues facing children and families in poverty. “There were many conversations about the most effective ways to reduce family homelessness,” Dr. Nunez said, “but more importantly, relationships established at the conference will continue to foster dialogue and action long after it is over.”

Resources

HEAR US, Inc.; www.hearus.us, Naperville, IL ■ Children’s Museum of Manhattan; www.cmom.org, New York, NY ■ Homes for the Homeless; www.hfhnyc.org, New York, NY ■ Horizons for Homeless Children; www.horizonsforhomelesschildren.org, Roxbury, MA ■ Project HOPE–Virginia, Education for Homeless Children and Youth; www.wm.edu/hope, Williamsburg, VA ■ First Step Staffing; www.firststepstaffing.com, Atlanta, GA ■ Ruth Fernandez Family Residence, Bronx, NY ■ Safe Haven Family Shelter; www.safehaven.org, Nashville, TN ■ The Family Place; www.famplace.org, Saint Paul, MN ■ Camelot Counseling Services; www.camelotcounseling.com, Staten Island, NY ■ New York City Department of Homeless Services; www.nyc.gov/dhs, New York, NY ■ The Creative Arts Team at The City University of New York; www.creativeartsteam.org, New York, NY.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

On the Record—

Trauma-Informed Care: Services That Heal

Trauma-informed care is a promising service delivery approach for those working with homeless and low-income people. UNCENSORED asked three professionals working with people experiencing trauma to share what unites their work, and what trauma-informed care means in practice.

Susan Reider, clinical director of Compass Family Services, is a licensed therapist with over 25 years of experience in nonprofits serving children and families. She holds a master’s degree in infant and parent development from Bank Street College of Education and a master’s degree in psychology from the San Francisco School of Psychology. Prior to working at Compass Family Services, she spent 15 years at the San Francisco Child Abuse Prevention Center, initially as a volunteer on the center’s parental stress line, later as a graduate intern and program director, and for three years as executive director.

Lorraine McMullin is the director of the Mental Health Association in New York State’s Parents with Psychiatric Disabilities Initiative and co-director of Building Connections: The Sexual Assault and Mental Health Project. She conducted research and evaluations on family homelessness, co-occurring disorders, health care, and the justice system. McMullin serves on the New York State Parent Education Partnership Steering Committee and the New York Protection and Advocacy for Individuals with Mental Illness Advisory Council. She is a parent and has used mental health, trauma, and homeless services.

Chrys Ballerano co-directs Building Connections: The Sexual Assault and Mental Health Project and coordinates the New York State Coalition Against Sexual Assault library, previously working as community educator and victim service coordinator at the REACH Center in Catskill, N.Y. She provides technical assistance, resources, and training throughout New York state, and leads presentations on the importance of using trauma-informed approaches in all work with homeless and low-income people. Ballerano also leads therapeutic drumming circles for people of all ages.

*****