Publisher’s Note

Dear Reader,

Whether you are a regular follower of UNCENSORED or a new one, we appreciate your interest in our publication and hope that you find the Spring 2013 issue to be enlightening.

We begin the fourth year of UNCENSORED with an on the Homefront section that includes the article “Not Alone,” a survey of children’s books that take on the theme of homelessness. Our National Perspective article puts the spotlight on a new report from ICPH, The American Almanac of Family Homelessness.

The feature articles in this issue take both broad and up-close looks at the work of serving poor and homeless families. Taking the macro-level view is our cover story, “Healthy Beginnings, Healthy Life,” which examines widespread efforts among medical professionals and others to ensure the well-being of mothers over the long term—not just the nine months from a child’s conception to delivery. The article “Lives in Transition,” meanwhile, is our on-the-ground profile of one facility, Transition House in Santa Barbara, California, which works with families who are motivated to overcome the crises that have led them to homelessness and rebuild their lives. Finally, the Historical Perspective looks at institutions of the past that housed poor and homeless children.

As we continue our mission to shed light on the challenges facing this nation’s impoverished families, we welcome comments, suggestions, and your continued interest in UNCENSORED.

Sincerely,

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, Publisher

President and CEO, Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Healthy Beginnings, Healthy Life:

The State and Future of Maternal and Child Health Care in the United States

by Lee Erica Elder

In 1990 the outlook for expectant mothers in Central Harlem, in New York City, was grim. Only 25% of pregnant women entered prenatal care in their first trimester, almost 20% of newborns had a low birth weight (less than five pounds, eight ounces), and the infant mortality rate was 27.7 deaths per 1,000 live births. When Mario Drummonds, executive director of the Northern Manhattan Perinatal Partnership (NMPP)—a nonprofit organization providing comprehensive health and support services to pregnant and parenting women—decided to focus his work in Central Harlem, many colleagues cautioned that his efforts would be fruitless. “I like a challenge, so I disregarded what my colleagues said, and I’ve been here 17 years,” says Drummonds. “And when we look at the data now, the infant mortality rate is around 7.5 deaths per 1,000 live births. We still have the highest low-birth-weight rate in the city, but it’s not 20%, it’s around 11.5%, and over 93% of women here in Harlem enter care in the first trimester.” Drummonds received an award from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in 1996 for his work in reducing the infant mortality rate in Harlem, and his health- and birth-outcome models are being replicated throughout the country.

Though overall statistics for maternal and child health care (or MCH, as public health advocates refer to the field) have improved in the U.S. since the 1990s, the numbers here still lag behind those in other countries; the infant mortality rate is more than twice that of nations such as Japan and Sweden, according to a new study by the Institute of Medicine.

Nursing student Sarah Gray ensures healthy breathing.

In general, health care access—or its lack—shapes the lives of mothers and children, and those who are homeless or living in poverty are the least likely to receive adequate treatment. “Women experiencing homelessness have high rates of pregnancy and are at higher risk for birth complications, like low birth weight, and nutritional deficiencies,” says social-work trainer Melissa Berrios-Johnson, MSW, of the Homeless Health Initiative (HHI), founded in 1988 at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “A disproportionate number of women of color experience homelessness. … It has been found that African American women have lower rates of participation in prenatal care, imperative for maternal/infant health. Preterm births occur more often among African American and Latina mothers than white women.”

Maternal and child health care organizations prioritize the health of mothers and children and try to create safe spaces for them to thrive. This work is particularly vital to women who are homeless. “We are dealing with a pretty entrenched population of women trying to improve their economic lot as well as their housing situations and, more importantly, their educational status,” says Drummonds. Women dealing with homelessness and transient situations comprise about 40 to 50% of NMPP’s clients.

Lifecourse Theory and “Medical Homes”

“Many are practicing maternal and child health on an old paradigm, focused on a nine-month period,” says Drummonds. Those professionals are “not concerned about … women’s health over a lifecourse—they are thinking about managing current pregnancy and then sending women out into the community without trying to provide services or do work during [the intervals between pregnancies].” Drummonds credits Dr. Michael Lu, associate administrator for Maternal and Child Health of the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), with revolutionizing the public health industry through his ideas concerning MCH lifecourse theory—a focus on the health of mothers and children over the course of their lives.

NMPP is a hub for several service programs that incorporate that idea. Baby Steps is a Healthy Families America (HFA) program funded by the New York State Office of Children and Family Services (OCFS); through NMPP, it provides home visits to expecting parents and parents of children up to two years of age, assessing their needs and capabilities and providing help as required. The Head Start program in Harlem and Washington Heights provides classroom education for children and links their families with social and community services. Drummonds is also excited about a grant that his organization recently received through the HRSA’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCBH) to fund Thrive, a between-pregnancy-care case-management program. Thrive works with women to extend the period between the birth of one child and conception of another to about 18 months.

“Prematurity is more impactful than heart disease and cancer—it’s a big problem and one that doesn’t get a huge amount of attention. No one hears from a preterm infant who dies.”

Health experts agree that in addition to care over a life course, every mother and child must have a stable “medical home” for optimal health. “A lot of times women have a number of medical providers who don’t know anything about their health histories and make proposals for health interventions that really are out of context,” says Drummonds. “A medical home has to have an extensive array of public health and clinical services that will hopefully address all the family’s needs over the life course.” An ideal medical home is a facility located in the client’s community, one that is family-focused and culturally sensitive and has an atmosphere of compassion.

As the concepts of lifecourse theory and medical homes suggest, the scope of MCH extends far beyond the doctor’s office and delivery room. “Some of us are attempting to get maternal child and public health clinical partners to understand that we have a much larger role to play and that we have to bring in and make connections to the business community, to make sure that women are employed and have the educational capabilities to get a good job, because we know the relationship between health and economic development,” Drummonds explains.

Preparing for a Lifestyle Change

HRSA-funded Healthy Start programs are leading the way in creating holistic, multidimensional support systems for pregnant and parenting women. The Healthy Start Initiative began in 1991 with 15 urban and rural sites in communities with exceptionally high mortality rates; it has grown to include 105 grantees nationwide currently. At NMPP’s flagship, Central Harlem Healthy Start, high-risk pregnant women (many of whom have previously had adverse pregnancies) are each matched with a case worker who addresses pre- and postnatal needs and helps to obtain services such as public assistance, job training, and domestic-violence intervention.

“The Healthy Start Program helped me a lot,” Valerie, the mother of a two-year-old girl, says. (As with other clients interviewed, her name has been changed in this article.) “When I first came to the program, I was four months pregnant. My case manager told me to prepare for a lifestyle change. She helped me understand that the baby would be more important and that I would not be able to go out as much. My baby and I went to Washington, D.C., with the Consumer Involvement Organization [CIO].” (NMPP’s CIO provides an opportunity for clients to engage with other mothers and participate in leadership and strategizing activities.) “I learned that I could be a great speaker once I get over my shyness. I also learned peer networking, and met other girls in similar situations. I also learned to be consistent and not just say I am going to do something, but to follow through with it. Now I am back in school working toward my associate degree.”

Children play at the facilities of Community Advanced Practice Nurses (CAPN) in Atlanta.

Similarly, Marlene, a mother of three children, says about Healthy Start, “I really like this program because I learn a lot and it motivates me to be better and become wise. I like the classes that teach us about our bodies and about health issues like diabetes, STIs [sexually transmitted infections], and smoking. The people are very nice and respectful—they make you feel welcome. They also help me with doctor’s appointments, metrocards, and stuff for the kids.”

Downstate New York Healthy Start (DNYHS) is a partnership of Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and three community-based organizations in New York City and Long Island: the Economic Opportunity Commission of Nassau County Inc., Queens Comprehensive Perinatal Council Inc., and Suffolk County Perinatal Coalition Inc. Women in DNYHS-served communities are at risk of poor birth outcomes due to poverty, unemployment, limited education, racial and ethnic disparities in care at time of delivery, and other factors. DNYHS works to connect women to medical homes and health care as soon as possible. DNYHS’s supportive case-management services include information and referrals, care between pregnancies, advocacy, and health education. In 2010 DNYHS implemented an innovative program designed to alleviate the depression experienced by at-risk mothers: the Circle of Caring (CoC) psychosocial support group for women during and between pregnancies. In this social-support network, women learn about the signs, symptoms, and treatment of depression as well as coping and stress-management skills. “The goal of the intervention is to provide support, education, and coping skills for women to learn to effectively negotiate stressful situations,” says DNYHS Senior Project Officer Vernique Montrose, MPH. Stress and depression, she added, not only affect women but also put strains on their families.

Why Care Is Important

In Philadelphia, HHI provides free services to children and mothers living in shelter, including primary and specialty care, dental screenings, autism and developmental screenings, access to health insurance, and health education. “HHI serves a population primarily comprised of women and children, the [fastest] growing segment of the homeless population, living in shelters in West Philadelphia,” says Berrios-Johnson. “Most families have survived trauma, such as violence, illness, and loss of loved ones, often compounded by the trauma of experiencing homelessness and moving into a shelter. Some mothers struggle with mental health issues, while many children have developmental delays and behavioral challenges.” In addition to parenting education, HHI offers Safe Sitter—a certified babysitting-training program that educates children (11 to 14 years old) in providing safe care for younger children, including CPR, and strengthens their future parenting skills.

An encouraging aspect of the current landscape of maternal and child health care is a focus on not just providing such care but educating providers about why it is so important. A core component of HHI’s success is increasing understanding of the grave effects of homelessness on the lives of mothers and children, and other MCH organizations agree that staff training and sensitivity are crucial. According to Montrose, “An educated, culturally sensitive environment—availability of translation services at medical centers, forms in multiple languages, confidential, private, and welcoming medical offices and personnel—and workforce is one way we can increase the chances that a woman will willingly and consistently take advantage of health care services. I think that in order to improve not only women’s health but population health, it is integral to have a well-trained, culturally competent workforce.”

A girl rides a horse as part of the Emerson Davis program of New York’s Institute for Community Living.

Stakeholders in the MCH community in Cincinnati, Ohio, are working together to meet the needs of at-risk women and families. “In Cincinnati there are pockets of very high infant mortality rates that are certainly more consistent with what you would characterize as developing countries,” according to Dr. James Greenberg, director of the division of neonatology at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMP) and co-director of CCHMP’s Perinatal Institute. “That’s not new, but what is new is an appreciation that we in health care and health care institutions had to become directly engaged in the health of communities. There is no question that preterm birth in the U.S. has a huge impact on quality of health on a national level. Prematurity is more impactful than heart disease and cancer—it’s a big problem and one that doesn’t get a huge amount of attention. No one hears from a preterm infant who dies. Loss of potential is more difficult to measure.”

Karen Bankston, associate dean of Clinical Practice, Partnership and Community Engagement and professor of clinical nursing at the University of Cincinnati, chaired a local government board focused on the reduction of infant mortality and the improvement of maternal and infant health. Bankston, who grew up in poverty, became a mother as a teen, and went on to earn a PhD, says that there is room for intervention to help young mothers with healthy decision making. “Some of the decision making really comes down to how [people feel] about themselves. I believe it is possible to overcome some of these challenges if the right initiative, actions, and environment are in place. It has to start early. We were [seeing] girls that were 11 years old [deliver babies], and that still happens in our community today. How does one equip an 11-year-old, if she’s being molested by a relative, how do we equip her to deal with that? One of the things we learned over the last few years is how much social determinants and things that affect environment influence choices women make and when and where they receive their care.”

Greenberg and Bankston are just two of the collaborators—among doctors, health agencies and advocates, community leaders, and others—building a multifaceted effort to eradicate problems facing mothers and children in Ohio. “We are working to organize a … collaborative to [implement] knowledge gained through our work, sharing that knowledge with relevant community agencies in a position to directly impact the problem of preterm birth at a community level,” says Greenberg. “There are extraordinary disparities that map with poverty and race in the U.S.—racial disparities around preterm birth and infant mortality are pervasive, and if we are really going to make an impact, we have to pay attention to and directly take on the issue of disparity. In Cincinnati, African Americans have a three-fold higher risk of delivering preterm than their white counterparts. Differences are not explained entirely—some relate to poverty and socioeconomic status and some do not. It’s tempting to say that it must be genetic, but we are fairly certain that while understanding genetics is important, hoping to identify a gene present in high-incidence populations is not the explanation. In a high-incidence area in Cincinnati, between 20 and 25% of babies are born preterm. That still means that 75 to 80% of women in the region are delivering in term, so what may be helpful is understanding resilience or reasons why many women in those areas do deliver to term, rather than focusing solely on the women who don’t. The nature of resilience can help teach us what it is about racism, environment, poverty, and so on that lead to a higher risk of preterm birth.”

Mental Health Is Key

For women experiencing poverty and homelessness, access to care and treatment for mental health issues are often elusive. “It is very difficult to obtain mental health services for women with depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and bipolar disorder,” says Linda Grabbe, family nurse practitioner at Community Advanced Practice Nurses Clinic for Homeless Women and Children in Atlanta (CAPN) and a clinical assistant professor at Emory University’s Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing. “Our patient population suffers from considerable chronic stress related to poverty and homelessness.” CAPN is a free, nurse-led clinic for homeless and uninsured women, children, and youth living in shelters, in transitional housing, or on the street. “Lack of access to health care providers and family planning methods or money to pick up a prescription leads to unplanned pregnancies. Often, postpartum insurance coverage ends before a woman obtains contraception, and a second pregnancy ensues,” says Grabbe. The clinic received a Healthy People 2020 Community Innovations grant, funded by HHS, to increase mental and gynecological health services to homeless youth. “By going to the shelter to screen youth for mental distress and to identify at-risk/suicidal clients, we were able to refer them directly to CAPN’s advanced practice psychiatric nurses or county mental health services,” Grabbe notes. “We also initiated a monthly educational session for the young women on health issues, which has been well attended.”

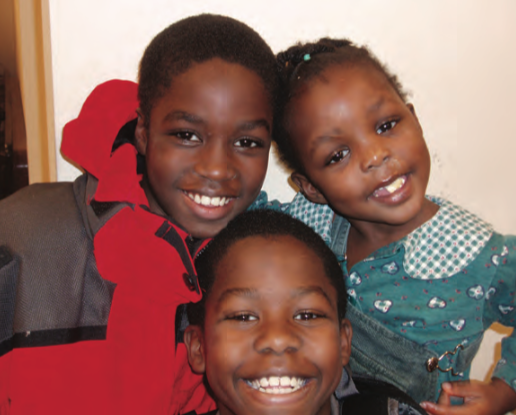

Children from homeless families can access free health care at the CAPN facilities.

Stella Pappas, a licensed clinical social worker, is executive vice president and chief operating officer of the Institute for Community Living (ICL); she oversees an organization dedicated to helping people with mental illness and developmental disabilities lead healthy lives. “It’s difficult for people to access help when they need it—we are a reactive system, not a preventive system, and a lot of time you can’t get mental health help for a family member or a loved one until something happens,” says Pappas. “We need to be able to access that care before something happens.” ICL provides innovative treatments, rehabilitation programs, and support services to adults, children, and families in the New York metropolitan area, through over 104 specialized residential and clinical programs that include but are not limited to supportive-housing services. Of particular note is the Brooklyn-based Emerson Davis program, which reunites and prevents separation of mentally ill mothers and their children. The program was founded 18 years ago to help clients who were recovering from substance abuse and other disorders and wanted to reside with their children while doing so. “There was a lot of stigma that mentally ill individuals could not be parents or raise their children successfully, but literature shows that as long as the child is safe, they thrive and prosper with their parents more than in any other environment,” says Pappas.

The stories of several ICL clients bear this out. Jennifer reunited with her two children, three and five years old, after moving into Emerson Davis in 2009. She continues to care for her children with the support of the program staff. Both children are attending school, and Jennifer has successfully completed training as a medical assistant.

Janice was reunited with her children in 2008, when they moved into the Emerson Davis family program. In 2010 the family moved into their own housing through Emerson Davis, allowing them to live independently while having access to services. Janice continues to live with her two sons.

Diana has remained sober since her admission into the Emerson Davis program, in 2006. After demonstrating that she was a stable parent, in September of 2012 she was moved into her own housing through Emerson Davis, where she enjoys even greater independence. Recently, her daughter successfully applied to several public schools for gifted students, and Diana is planning to become a certified alcohol and substance abuse counselor (CASAC).

Annette is a substance-abuse counselor for the Inpatient Medically Managed Detoxification Unit at St. Mary’s Hospital of Brooklyn. She is also an ICL client. Born and raised in the Bronx, she has three children (a 24-year-old and 13-year-old twins). In 1994, during the re-entry phase of treatment for alcoholism, she was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and was involuntarily admitted to a hospital, where her condition was treated and stabilized.

While at Emerson, Annette attended a Mentally Ill Chemical Abuser (MICA) Outpatient Program, through which she developed interpersonal and coping skills and participated in programs to maintain her sobriety. Support services at Emerson enabled Annette, her children, and other family members to make the transition to an alcohol- and drug-free lifestyle. She returned to college and obtained a BS degree, after which she assumed her present position at St. Mary’s Hospital. In a few months, she will complete educational training for the CASAC exam. Annette’s professional goal is to obtain a master’s degree in health care administration and to become a grant writer for early-intervention health care programs that target at-risk communities.

The landscape of MCH is expanding. Caregivers are focused on eliminating barriers to health care for mothers and children, no matter their economic situation. “Women are often the gatekeepers in their family,” says Montrose. “If public health professionals can maintain the woman’s commitment to improving her health, we will have successfully gained entry to improving the health trajectories of her immediate family, community, and hopefully the nation.” Such care and attention will give more families the chance to thrive for generations to come.

Resources

Northern Manhattan Perinatal Partnership; New York, NY ■ U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, D.C. ■ Community Advanced Practice Nurses Clinic for Homeless Women and Children in Atlanta; Atlanta, GA ■ Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing; Atlanta, GA ■ Homeless Health Initiative; Philadelphia, PA ■ Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; Philadelphia, PA ν Heath Resources and Services Administration; Washington, D.C. ■ Downstate New York Healthy Start; Jamaica, NY ■ Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health; New York, NY ■ Economic Opportunity Commission of Nassau County Inc.; Hempstead, NY ■ Queens Comprehensive Perinatal Council Inc.; Jamaica, NY ■ Suffolk County Perinatal Coalition Inc.; Patchogue, NY ■ Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center; Cincinnati, OH ■ University of Cincinnati; Cincinnati, OH ■ Institute for Community Living; New York, NY.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Lives in Transition:

Santa Barbara’s Transition House Gives Homeless Families a Path to Independence

by Carol Ward

Feature articles in UNCENSORED often take a broad view of issues involving poor and homeless families, briefly highlighting a variety of people and organizations working on a specific aspect of the homelessness crisis. In something of a departure, the following article focuses on one place, Santa Barbara’s Transition House—looking in-depth at its mission, its nuts and bolts, and the bravery and determination of its residents, as well as the challenges they face. We think that readers will find here “the universal in the particular,” illuminations of common concerns in the stories of a few.

In the spring of 2012, Megan felt that her life was finally turning around. The single mother of a ten-year-old boy was regaining custody of her son after more than a year away from him; she was engaged to be married to a man earning a good salary; and she was working full-time while recovering from drug and alcohol addiction.

But in one weekend, the world she had carefully built shattered. Megan (not her real name) found drugs in her husband’s possession. Fearful for her own sobriety and cognizant of her precarious position with regard to custody of her son, Megan made the difficult choice to cut ties to her fiancé.

“In the course of 48 hours I went from having my dream wedding to sleeping on the floor of my dad’s trailer,” Megan says. A few days later, for the second time, she ended up at Santa Barbara’s Transition House family homeless shelter.

In the autumn of 2012, Katie (not her real name) was also on her second go-round at Transition House. The 24-year-old grew up in what she describes as a “privileged family” but sought shelter for the first time shortly after having her first child as a teenager.

Like Megan, Katie thought she was building the ideal life, marrying a man who worked while she stayed home with the baby. But “personal issues”—in the form of drug and alcohol abuse for both—“got in the way.”

During her second stay at Transition House, Katie gave birth to her second child. Her husband tried to enter the program as well but was refused because of continuing substance abuse, Katie explains.

Although still married, Katie is now questioning her commitment to her husband. “I really want to pull my life together, get a place and get my kids safe,” she says. “He was a liability and was bringing us all down.”

Transition House’s emergency shelter provides lodging and meals for up to 70 people each evening.

Megan and Katie are among the roughly 600 shelter, transitional-housing, and homelessness-prevention clients Transition House served in 2012. In September Katie was living at the group’s emergency shelter, the point of entry for Transition House clients, while Megan had “graduated” to a second-stage, transitional facility called the Firehouse.

The first floor of the Transition House shelter includes a large dining room, a kids’ room and library, a laundry and health room, and other amenities. Outside is a small, enclosed play area. Families are housed upstairs in rooms that vary in size but are usually just large enough to fit a bed for each family member, a chest of drawers, and a small television. At the Firehouse the sleeping rooms are of similar size and style, but the large communal kitchen and living areas allow families to interact.

Transition House has been serving homeless families since 1984, when representatives from a variety of social-services groups and faith-based organizations came together to address the issue of family homelessness. From that meeting, 12 religious centers opened their doors to homeless families on a rotating, month-to-month basis. (Other than a prayer of thanks before the evening meal, there is not a strong religious component to the Transition House program.) Transition House found its first dedicated space in 1985. In the 1990s the facility moved to its larger, current home.

Transition House focuses on helping motivated families climb out of poverty through a strict program that includes infant and child care, employment development, three stages of housing assistance, and other services. Clients are considered to be motivated if they are willing to embrace the program—including the fairly rigorous rules laid out by Transition House, such as curfew, money-management requirements, and attendance of classes. Clients cannot use drugs or alcohol and are subject to random testing. Those who balk at the rules are not considered to be motivated.

Shelter clients are referred to Transition House by other local shelters (which serve primarily individuals), social-service agencies, County of Santa Barbara social workers, Child Welfare Services, the local school district, churches, and individuals who are familiar with the agency. Transition House does not employ “street outreach” workers, but those employed by the county can make referrals to the facility. While there is not technically a maximum number of times that Transition House will serve clients, the limit is usually two, very rarely three; exceptions are made on a case-by-case basis, if the staff feels that a given client is motivated.

Kathleen Baushke, executive director, notes that Transition House is the only facility in Santa Barbara serving homeless families exclusively. At any given time there is a waiting list of 20 or more families hoping for spots in the program.

Even in this upscale community, “poverty is always the issue,” Baushke says.

In addition, “Maybe a quarter of our clients have mental-health issues within the family, although they might not be so severe that they are causing the homelessness,” she says. “Probably a quarter of our clients have a substance-abuse history. It may be in the past. They may not be actively using or needing to use, but it has helped define their situation.”

High Costs, Low Wages

The city of Santa Barbara is one of the most expensive places to live in the country. According to the Web site Sperling’s Best Places, the city of about 88,000 on California’s central coast has a median home cost of $674,700. Santa Barbara’s cost of living is 104.7% higher than the U.S. average.

For all the wealth enjoyed by many of the city’s residents, those working part-time or at near-minimum-wage jobs find life in Santa Barbara to be challenging at best.

“Santa Barbara has stratified, as much of the country has, in such a way that the distance between the top and bottom of the economic ladder gets bigger and bigger,” observes Jim Buckley, president of the board and a volunteer at Transition House. “Many people have worked here for years but have reached a point where the money they’re bringing in doesn’t equal what they need to spend to live here. Some crisis will hit and suddenly they need us, and we’re here for them.”

Finding and securing affordable housing is a crucial issue for the city’s lowest wage earners. “Even though the cost of living is so high here, it is a desirable area to be in, so vacancy rates are low, and that’s part of the challenge,” Baushke says.

Another, bigger challenge is simply cost. According to city-data.com, the median asking price for vacant rental units in Santa Barbara in 2009 was $1,681 per month. At that average rate, roughly half of the before-tax income of a family or individual earning $20 an hour, 40 hours a week, would go to rent. Those earning half that wage—still above minimum wage—find it nearly impossible to make ends meet.

Doubling up or settling for something smaller than desirable often is not an option for families. Because of the low supply of rental housing, landlords can put constraints on family size or on the number of inhabitants in individual units.

Jose and Juana, residents of the Transition House emergency shelter along with their two young children, feel that the program is working for them. “We’ve saved a lot of money,” says Juana, who notes that Jose’s current job has improved their financial situation. Still, they fear having to live without support; Juana gave birth to their second child while living at Transition House and was actively looking for work in October 2012, but the barriers to self-sufficiency are daunting.

“We’ll have to get a two-bedroom—they [landlords] won’t accept our family size in a one-bedroom,” Jose predicts. “I just don’t see how we can do that.”

Katie is facing a similar roadblock. “Santa Barbara is a tough town,” she laments. “It’s a beautiful place to live, but rents are so high it makes it hard for middle and lower-class people.” Even if she separates from her husband, Katie says, she and her two small children will likely be forced to rent a two-bedroom apartment, which is currently far out of reach financially.

Taking on a Housing Role

Transition House is far more than an emergency shelter. For the past decade or so, the nonprofit has taken a pro-active role in developing affordable housing in a city that lacks options.

Baushke started as a volunteer at Transition House in 1992, when its resources for clients consisted of a 35-bed shelter and no support services. Since then, Transition House’s shelter has moved to a much larger location that can accommodate up to 70 residents. The organization purchased a 13-unit affordable-housing complex called Casa Marianna in 1999, expanding it to 19 units, and leases the Firehouse from the Housing Authority of the City of Santa Barbara.

A family who resided at Transition House now have their own apartment.

More recently, in 2012, Transition House completed construction of a new “Moms’” facility. The eight-unit apartment building—adjacent to the group’s administrative office, in downtown Santa Barbara—houses low-income families, with particular emphasis on those that include adults with special needs. The families can participate in case management. Within the same structure, Transition House added a new infant-care center to serve its clients as well as other low-income community residents.

The Moms’ project was fraught with challenges related to cost, tax credits, and issues involving building requirements and contractors. Those challenges and the uncertainty of funding going forward are forcing Baushke and Transition House to re-evaluate future plans. (More than one-third [34%] of Transition House funding comes from private individuals. Local foundations provide about 21% of funding, while rental income from owned housing accounts for 16%. Federal funding [16%] and local and state government funding [13%] make up the balance.) The Moms’ project relied extensively on government funding, and the strictures involved with that money made the undertaking extraordinarily challenging, Baushke says.

“It’s in our strategic plan to acquire more real estate, but we’re at a point where it’s very difficult to do that because of redevelopment-agency money going away, which we would rely on for local funding,” Baushke says. “The only source, really, is tax credits, and they are so competitive. When we have a housing authority as great as the one we have here, why would we compete against them for money to develop affordable housing? They should do it.”

“I think having a connection to more affordable housing in the future is definitely in the cards, but probably the structure is going to look different,” Baushke continues. “Maybe it’s a property they [the housing authority] would acquire; then we would do service delivery if we could find the funding.”

Staff

Transition House employs 34 people, 23 of whom work full-time. This number includes case-management staff, shelter-facility managers, and administrative/fund-raising staff. For case-management positions, Transition House does not require specific education or training because the positions are not clinical.

“We are more concerned that case managers have past experience working with the population, knowledge of local resources, and a commitment to Transition House’s mission to provide families with tools and life skills to achieve financial independence,” Baushke says. “We try to keep a variety of expertise in our case-management department. For example, we have someone with drug and alcohol counseling experience, someone with expertise in domestic violence, another with training in childhood development, and someone with experience working with clients with mental health issues.”

“In particular, we look for people who understand budgeting and planning,” Baushke continues. “If a case manager cannot balance their own checkbook, they aren’t going to be able to train a family on how to manage their household finances.”

The Full Package

Clients at the main Transition House shelter abide by strict rules of conduct designed to make sure families stay focused on their goal of living independently.

“We’re not just warehousing people,” says Buckley. “If they’re just looking to crash, they’re not going to crash here very successfully. But if they’re looking to change themselves and get back on track, we’re going to be there 100 percent.”

At the main shelter, all family members must leave the facility during the day—for work, job searches, or school—then return at 5 p.m. or so. Passes are issued in the evening for events such as religious services, substance-abuse recovery meetings, or job interviews, but otherwise clients are required to eat dinner at the shelter and remain there through the night.

Dinner is provided nightly by a rotation of volunteer groups, who also prepare sack lunches for the next day. Breakfast foods are available each morning. In addition to the laundry facility, there is a clothes closet on site. Bus tokens are available for travel to work.

Families incur virtually no expenses while living at the shelter, according to Baushke. “Our policy is that 80 percent of a family’s expendable income is to be saved,” she adds. “That’s a really valuable part of our program, which came about out of necessity because people need a security deposit and first month’s rent” when they leave Transition House.

A local musician visits with Transition House children during evening enrichment to teach them about different musical instruments.

The budget plan is the backbone of the Transition House program and, to many clients, its most difficult component.

“People say budget plans are more difficult to talk about than sex,” program director Debbie Michael declares. “It’s a really difficult part for a lot of people, especially those who have always spent and never budgeted. We have spending plans and weekly expense sheets to keep track, and we try to whittle down spending as much as possible.”

Transition House even offers banking services to help those who can’t open bank accounts due to outstanding debt, legal status, or other issues.

“We have a safe—only five of us know the combination,” Baushke explains. “They come to us to do deposits and withdrawals, then we offload money from the safe into a bank account. It’s an unusual thing to do but it works really well.”

In addition to banking, Transition House offers a slew of support services, such as job-skills, computer, ESL (English as a second language), and parenting classes, as well as children’s programs. Clients are expected to take part in classes and to meet regularly with caseworkers to assess progress.

Michael describes the transition to such a structured and crowded environment as being hugely challenging for many clients.

“They’re living in a crowded situation with so many different cultures and languages and parenting skills, all just kind of thrown into this building,” Michael acknowledges. “Then there are a ton of rules they have to follow, and on top of that all the program requirements.”

“We know that if they can follow the program—and we really try to tailor it to individual families—they can get from point A to point B and be in a much better place,” Michael continues. “Most people understand that, but still, to make those personal changes is really a struggle for a lot of people.”

Jose and Juana acknowledge that living at Transition House is easy in that virtually every need is met, yet challenging in the day-to-day.

“Sometimes I just want to get out, take my daughter to the park or just take a walk,” Jose says. He knows he can’t do those things, though, and tries to keep matters in perspective. “They’re helping us out, so we’re going to do what we have to to move on.”

The Next Step

Jose and Juana want to move on to the next step of the Transition House experience, the Firehouse. Katie does as well. Clients spend at least two months at the Transition House shelter, with most taking an additional two months before they are ready to move on. Because of limited space, only about 25 percent of shelter clients get the chance for the less intrusive Firehouse experience, while others are forced to rent on the open market or obtain Section 8 housing vouchers, according to Michael.

Families living in the shelter can apply for acceptance into the Firehouse. The family must have saved money for a security deposit and must have an income (through either employment or entitlements) that will allow them to pay rent. They must demonstrate in the application that a stay in the Firehouse will provide the additional time they need to be ready to move into permanent housing. Because families must pay rent at the Firehouse, they need to include in the application a reasonable monthly spending plan showing the household income and expenses. Similarly, Firehouse residents can apply for the permanent supportive housing program, Casa Marianna. They must meet low-income requirements, demonstrate the ability to pay their rent, and describe how they will benefit from continued support services to ultimately achieve economic stability.

Transition House’s emergency shelter serves families with children.

At the Firehouse, clients can come and go as they please but are expected to work, paying rents much lower than on the open market. Rules are far less stringent—but still there are no visitors and no alcoholic beverages allowed on the premises.

One Firehouse resident, Ellen (not her real name), is able to say that she, her husband, and their son are pulling their lives together after financial disaster.

“This allows us to save money, which is phenomenal,” Ellen says. Her stay at the Transition House shelter forced her to “work through the anxiety of dealing with past debt,” and her current situation allows her to address that debt head-on.

“It’s because of them [Transition House staff] that I think living a normal life is really possible,” Ellen adds. “We have to do the hard work but the motivation comes from them.”

There are few affordable options for struggling families beyond the Firehouse. Space in Casa Marianna is limited. The newly constructed Moms’ housing is already full, and priority is given to families with special needs that might limit the adults’ ability to work full-time.

Even after her months at Transition House and the Firehouse, single mother Megan finds the prospect of living independently to be intimidating. “I look every day for a second job,” she reports, noting the need to supplement the near-minimum-wage income from her current full-time position. “I just don’t foresee myself making enough to live and support my son.”

Megan’s worry notwithstanding, Transition House has a remarkable success rate, with seven of every 10 families it serves successfully transitioning to independent living.

“One thing we try to repeat to our clients is that this situation is so temporary in their lives,” Michael says. “There is a way out, and that really resonates with a lot of people. We tell them, just bite the bullet and live frugally, so you can get out of here and never have to see us again.”

Resources

Transition House; Santa Barbara, CA ■ Sperling’s Best Places; Portland, OR ■ Housing Authority of the City of Santa Barbara; Santa Barbara, CA.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The Historical Perspective—

Finding Homes for Poor Children: Orphanages and Child Welfare Policy

by Ethan G. Sribnick and Sara Johnsen

In 1872 Sarah Meyer appealed to the Hebrew Orphan Asylum of New York to accept Philip, her eight-year-old son. Sarah, a 35-year-old immigrant from what is now Latvia, had found work at the Home for the Aged to help support both her children and her elderly mother. Yet her work made it difficult to care for the reportedly rambunctious Philip. “Being obliged to be away from my house all day long,” Sarah wrote, “and having a mother, who is too old to take care of the child, the same is left to itself exposed to every danger and led to mischief.” Her application made no mention of her husband, but most likely he had either died or abandoned the family. Two of Philip’s brothers already lived in the orphanage, but he would leave behind two sisters. Sarah probably planned to reunite all her children at some point in the future. Three days after she applied, Philip moved to the Hebrew Orphan Asylum, an imposing structure on the corner of East 77th Street and Third Avenue.

More than 130 years later, in Jacksonville, Florida, Sylvia Kimble’s family faced similar challenges: low wages, high housing costs, unstable family structure, and the need for child care. Sylvia’s six grandchildren—three of whom had psychological problems—ended up in her custody after her daughter and daughter-in-law were jailed on drug charges. Sylvia herself had little parenting experience; during the 20 years she spent homeless, she had left her children with her own mother. But despite her background and poverty, the state of Florida decided in favor of having the grandchildren remain with Sylvia, now 46 years old and clean for 11 years, rather than removing them from the home. The state provided in-home counseling, therapy for the children, and cash assistance. “Family services has been a blessing,” the grandmother declared. Soon her daughter, still undergoing drug rehabilitation, was able to move back into the home. With the support of the state, Sylvia put a down payment on a subsidized house, securing a permanent home for her large, extended family.

The Hebrew Orphan Asylum of New York. This building, opened in 1884 at 136th Street and Amsterdam Avenue, housed up to 1,755 children at a time. Despite its institutional appearance, administrators imagined the Orphan Asylum as a large, efficient home. Collection of the American Jewish Historical Society.

The outcomes of these two families’ stories are extremely different, thanks to the public-welfare infrastructure that developed during the century separating them. Where Sarah Meyer and many other 19th-century parents chose or were forced to place their children in institutions, today the state, as in the case of Sylvia Kimble’s family, favors preserving families whenever possible. Public-assistance programs, day care subsidies, and family homeless shelters all are intended to prevent poor families from being broken up. Even child-protection investigators attempt, except in cases involving the most heinous and violent acts, to keep children with their parents and to provide services to prevent abuse or neglect that could affect the children’s well-being. When a child is removed from his or her parents, every effort is made to place the child in foster care, a substitute home environment.

Family-preservation programs are a relatively recent innovation in the history of family poverty. Before the 20th century, the practice of placing one’s child in an institution, voluntarily or otherwise, was grounded in a belief that children would be better served by growing up in congregate institutions, or orphanages, than by living in poverty with their families. As attitudes toward the importance of the family and the role of the state changed over the 20th century, social-welfare agencies gradually shifted resources toward programs that helped families stay together.

Congregate homes for children in the United States date back to the 1700s. As cities grew in the years after the Civil War, the number of institutions and children living in them increased exponentially. The late 19th century became the heyday of large congregate institutions for children: across the country, the number of orphanages tripled between 1865 and 1890. These new asylums expanded their mission beyond that of the orphanages that preceded them; no longer excluding those who were not orphans or half-orphans (children with one living parent), they began admitting destitute children with both parents living.

The new approach of orphan asylums and other institutions was based in middle-class beliefs about the home and childhood that had emerged over the 19th century. Urban middle-class families had become focused on creating homes that were distinctly separate from the world of work. In these homes children would live sheltered lives free from the stresses of the adult world. Middle-class married women, also excluded from the male realm of work, were expected to oversee the rearing of children. Based on these standards many less-privileged households in New York and other cities—where mothers and older children were often sent out to work—failed to meet the middle-class definition of a proper home. These poor children were, according to middle-class standards, missing out on a proper childhood.

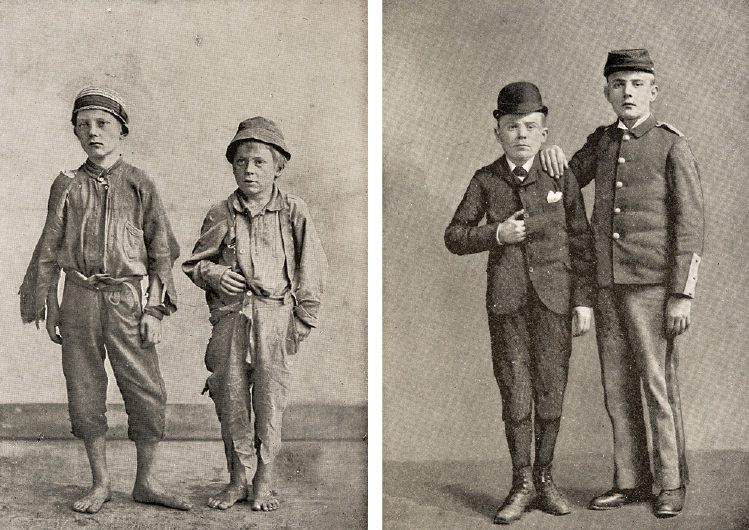

Two brothers, before and after their five-year residence in the Catholic Protectory. Institutions tried to produce adults whose appearance, work habits, and religious views and practices reflected middle-class ideals. The Protectory used these images as proof of its success in its 1892 annual report. Collection of the New-York Historical Society.

Orphan-asylum administrators believed that compared with destitute and struggling parents, they could provide a more “homelike” environment and ensure more idyllic childhoods for the boys and girls in their care. The managers of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum, for example, imagined their institution as a large, efficient home. “Order and mutual love,” the superintendent wrote in 1868, describing the asylum’s guiding principles, “are the pillars which sustain the happiness and prosperity of every household.” Similarly, the Orphans’ Home and Asylum of the Protestant Episcopal Church in New York explained, “It has been our aim, as managers of the Orphans’ Home, to make it as little as possible like an institution, and to promote by every means in our power, the home-feeling among its inmates.”

In spite of the claims of the managers that orphanages acted as middle-class homes, life in an institution with hundreds of other children had little resemblance to life in a family setting. This was immediately clear to children upon their arrival in these often massive places. Decades later, Sarah Sander recalled the day in 1894, after the death of her father, that she and her sister, Charlotte, arrived at the Jewish Orphan Asylum in Cleveland. The two girls—five and six years of age at the time—were taken to a wardrobe room, where all their clothing was removed, then to the basement for baths in “a large pool of green water,” then back to the wardrobe to be dressed in the Jewish Orphan Asylum uniform. Finally, the girls were taken to the barber, who cut their long hair to the length of “a boy’s haircut.” “Looking at Charlotte and myself in the mirror,” Sarah recalled, “I felt we had lost our identity. We cried.” Soon afterward Charlotte wrote her mother, “I don’t like it here—I was crying and I want to go home—you must take me home—you must take me home … you must take Sarah and me home.”

Life in these institutions was structured and regimented. Henry Bauer, who came to live in the Hebrew Orphan Asylum in New York at age nine, recalled his typical day as, “Get up, say your prayers, get your breakfast, go to school, come back, study your lessons, study Hebrew, get your supper, and go to bed. Very little play, very little play!” At the Catholic Protectory, an institution for vagrant and homeless children just outside New York City, children arose just before six o’clock in the morning, and after that virtually every hour of their day was scheduled for prayer, school, or work, with only a few minutes permitted for recreation. At the Hebrew Orphan Asylum during the 1880s, the bedtime routine was conducted “by the numbers.” Children had to get undressed based on numbered commands such as, “1. Jacket off, 2. Sit down, 3. Right shoe off, 4. Left shoe off.” This continued up to, “10. Get in bed.” Such a rigid system led to frequent infractions, and children often received corporal punishment. For worse offenses they were denied meals or were forced to stay in solitary confinement.

This structured environment helped administrators keep order among hundreds of children, but it also reflected the institutions’ mission to inculcate values such as discipline. At the heart of all these places was an effort to educate the children and provide them with both greater economic opportunity and an improved sense of morality. At the Catholic Protectory children received instruction in “the various branches of learning, as reading, writing, and arithmetic,” but, as the brother who ran the boys’ section explained, the education program aimed at more. “Our great aim is to mould their hearts to the practice of virtue,” he declared, “and, while we make them worthy citizens of our glorious Republic, to render them fit candidates for the heavenly mansions above.” At some institutions, such as the New York Hebrew Orphan Asylum, children were sent to local public schools for formal instruction. Still, the asylum took responsibility for ethical and religious training as well as preparing children for the workplace.

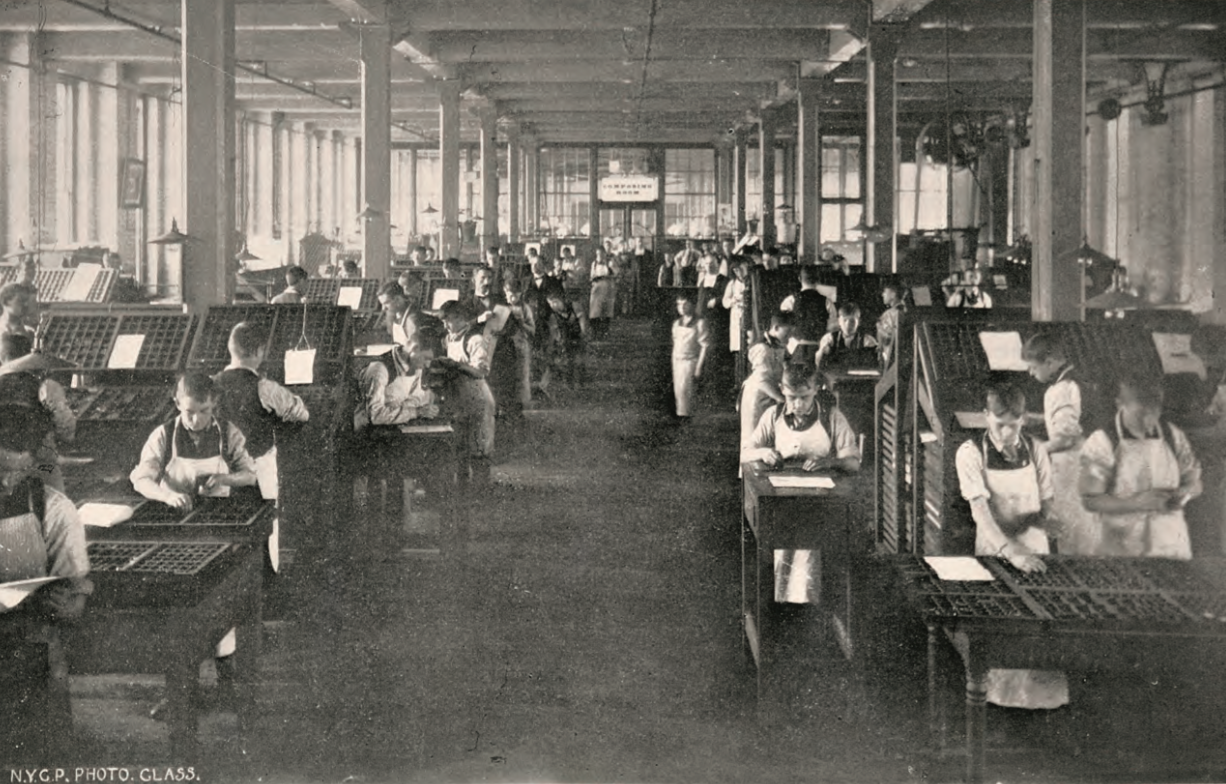

Extensive vocational training for older children helped these institutions fulfill their mission to improve their charges’ economic opportunities. At the Catholic Protectory boys learned to make shoes and hoopskirts; they were also taught the trades of printing, carpentry, and baking as well as the skills needed for work as blacksmiths, chair caners, tailors, and machinists. This instruction came in addition to the skills acquired while running the farm that provided the institution’s milk and vegetables. Girls were trained mostly in dressmaking and domestic services. The Hebrew Orphan Asylum opened both shoemaking and printing shops, providing entry into these professions.

Residents in the courtyard of the Home for the Friendless, c. 1864. Established by the American Female Guardian Society, the home provided housing and job training to the “unprotected female whose only crime is poverty and the need of employment.” Collection of the New-York Historical Society.

In spite of the difficult life most children experienced in these institutions, many families voluntarily places their children to asylums. Doing so allowed parents to pursue work without worrying about caring for, feeding, and housing children, giving the parents time to get on firmer financial footing before resuming their responsibilities. Interestingly, many parents, such as Sarah Meyer, chose to send only some of their children to the asylum. The decision appears to have been made based on age and gender, with parents keeping at home very young children and older children who could work and add to the family income. Other children were placed in institutions after being found on the street by the police or were removed from their parents’ homes by private child-protection organizations such as the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

No matter the path by which children arrived at institutions, once they were under an asylum’s care, the administrators quickly asserted their power to limit the children’s contact with their families. Over much of the 19th century, the managers of these congregate homes feared that parents were a negative influence on their children and attempted to restrict interaction. Often, parents were permitted to visit for a few hours each month, but visiting times and rules varied greatly by institution. In the 1880s, for instance, the Hebrew Orphan Asylum in New York decided to limit its visiting hours to one day every three months. The asylum also barred parents from giving cash or candy to children as presents. As attitudes toward the role of parents changed in the early 20th century, asylums began to loosen their restrictions on parental visitation. By the 1920s many institutions were actively encouraging parents to spend as much time as possible with their children.

Children’s time in institutions was relatively brief. One historian has estimated that children typically stayed in orphan asylums for between one and four years. For some children, especially those with two living parents, stays in an asylum could be quite short, often less than a year. Once a family’s financial crisis was resolved, a child who had been sent away usually returned home. Even parents whose children had been removed by child-protection agents could reclaim their children after they had demonstrated to the court that they were now fit parents. Children with no living relatives spent longer periods in institutions. These children were often placed in apprenticeships or boarded with families once they reached their early teenage years.

There was a long tradition of contracting with households to place older children as servants or apprentices. By the mid-19th century these contractual agreements, known as indentures, had declined; instead, institutions placed children in what became known as free homes, with loving families who would voluntarily provide care. The Roman Catholic Orphan Asylum of New York, for instance, was placing children in free homes as early as the 1870s. By the late 19th century, however, a lack of households willing to take on others’ sons and daughters made it difficult to place children. To find homes for their charges, institutions placed them in boarding homes, paying substitute parents to care for children. This practice, which became common in the early 20th century, set the foundation for modern foster care.

Composition room at the Catholic Protectory. At most institutions for children, residents learned trades that could support them in adult life. In this photo, from 1898, boys compose type for printing. Collection of the New-York Historical Society.

The 20th century saw a deep reevaluation of child-welfare practice. For most of the 19th century, managers of institutions and agents of organizations including the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children believed that poor children were often better served if they were separated from their parents. By the 1900s, however, there was a growing belief that care of a child in a family was the best course in most cases. When child-welfare experts met at the White House at the invitation of President Theodore Roosevelt in 1909, they recommended that no child be removed from his or her parents due to poverty alone.

Based on this new perspective advocates pushed for, and many states passed, mothers’ pensions—public payments to widowed or deserted mothers so that they could care for their children at home. The passage of these laws led to a slow decline in the number of children in asylums. In the ten years following the passage of the mothers’ pension law in New York, the number of institutionalized children in the state decreased by around 30 percent. Nationally, by the late 1920s, the number of children supported by mothers’ pensions surpassed the number of children in orphan asylums. When mothers’ pensions were incorporated into the national Social Security Act of 1935 in the form of Aid to Dependent Children (later Aid to Families with Dependent Children), institutions for children seemed endangered. Still, some continued to care for orphans and other children through the 1940s, and a few lasted through the 1960s.

Institutions that shape the lives of America’s poorest families and children changed remarkably during the 20th century. In the 1870s relinquishing children, at least temporarily, was often the best strategy for family survival. Today, the economic conditions that destroyed homes 130 years ago still make it difficult for families to secure adequate housing, jobs, and child care, but the existence of social-welfare programs including TANF, food stamps, and child-care assistance ensure that most poor children can grow up in families. Nineteenth-century institutions strove to release the greatest potential in their young charges—to provide a developmental experience that would ensure their greatest economic opportunity and allow them to become moral, upstanding citizens. These goals, while not always explicitly stated, still inform today’s child-welfare policies, but the state’s attitude toward poor parents has changed substantially. Today, well-being for poor children is reached through investment in the entire family.

Resources

Ashby, LeRoy. Endangered Children: Dependency, Neglect, and Abuse in American History. New York: Twayne Pub., 1997. ■ Bogen, Hyman. The Luckiest Orphans: A History of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum of New York. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992. ■ Brace, Charles Loring. The Dangerous Classes of New York, and Twenty Years’ Work Among Them. Chestnut Hill, MA: Adamant Media Corporation, 2001. ■ Hacsi, Timothy A. Second Home: Orphan Asylums and Poor Families in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997. ■ Hawes, Joseph M. Children in Urban Society; Juvenile Delinquency in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971. ■ Hebrew Benevolent Society and Orphan Asylum of the City of New York. “Admissions and Discharges, 1862–1884,” Box 18, Folder 1. Records of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum of the City of New York, American Jewish Historical Society, New York, NY. ■ Pickett, Robert S. House of Refuge: Origins of Juvenile Reform in New York State, 1815–1857. 1st ed. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1969. ■ Polster, Gary Edward. Inside Looking Out: The Cleveland Jewish Orphan Asylum, 1868–1924. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1990.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Not Alone:

Children’s Books Spark Discussions About Homelessness

by Melissa Walker

*White Tiger Press is an independent publisher of books about family poverty and homelessness for both children and adults in collaboration with the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness.

For kids, books are safe windows into worlds of adventure, magic, and real-life feelings and situations not yet experienced. They are also places where wide-eyed new readers look for reflections of themselves, to find validation, comfort, and insight.

The children’s books described below all serve to shine a light on aspects of homelessness—through furry characters, undersea creatures, and everyday kids. Each one offers points for discussion as well as thought-provoking moments for readers of every age.

For readers in kindergarten or older:

Ears Up, Ears Down, by Ralph da Costa Nunez with Margaret Menghini; illustrations by Madeline Gerstein Simon (*White Tiger Press, 2012). A dog called “Ears Up” finds himself out of a home after the closing of the junkyard where he has lived since he was a pup. Sadness brings his ears low, and the family he meets along the highway calls him “Ears Down.” Together, Ears Up, Ears Down and his new friends travel to a tent city where many homeless families live, and our canine hero meets many new and interesting people and learns the ups and downs of major life change. A separate activity book illuminates the story through games and discussion questions. Ears Up, Ears Down gives readers a lovable character to relate to and root for as he searches for a home and a new purpose.

Mango’s Quest, by Ralph da Costa Nunez with Robyn Schwartz; illustrations by Amarides Montgomery (*White Tiger Press, 2008). When Mango the hamster’s classroom cage gets overcrowded, he has to find refuge elsewhere. After being turned away by the classroom’s other animals, he stumbles upon a kindly old mouse who runs a shelter of sorts in the school library. The next day the students in his class, after brainstorming to help their friend find a new home, come up with a creative way for Mango to have a comfy wood-chip pile of his own again. This story is a perfect lead-in to a classroom discussion about homelessness. A related activity book provides opportunity for reflection through games and questions.

Where Can I Build My Volcano?, by Pat Van Doren; illustrations by Wanda Platt (HEAR US, Inc., 1998). Susan, a third-grader, has a stuffed bear named Ted and a best friend named Ellen. When her aunt’s house gets too crowded, Susan and her mother must live out of their car, and eventually in a shelter, where the young girl feels vulnerable and afraid. The biggest sources of stress in Susan’s life are the secrets she keeps—about her homelessness, why she has rips in her dress, and why she never has a pencil in school. With the help of a loving mother, a kind teacher, and a worker at the shelter, Susan starts to see the positive parts of her life: she has a warm place to sleep and someone to care for her. Though Susan worries that she will lose her best friend if the truth is revealed, she discovers the relief that comes with being honest and not keeping secrets. This book explores the daily details and unique challenges of living as a homeless child, as well as the hope and encouragement that the right people can provide.

Scrawny Cat, by Phyllis Root; illustrations by Alison Friend (Candlewick Press, 2011). Scrawny Cat used to have a home and a girl who loved him, but now he’s wandering and afraid, wondering where he belongs and whether he’ll ever be warm and cozy again. The story of a lost cat and his misadventures on the street with strangers and barking dogs will resonate with any child who has ever felt alone, lost, or without a home. The hopeful ending showcases an inspiring inner strength.

Cooper’s Tale, by Ralph da Costa Nunez with Willow Schrager; illustrations by Madeline Gerstein Simon (*White Tiger Press, 2000). When the old man he lives with disappears suddenly, Cooper the pink mouse is thrown out of his home. He wanders to the playground, where he sees three children who are not playing but sitting apart from the other kids. “We’re homeless,” one of them, a little girl, tells him. “We don’t feel different. But here at school they say we are.” Cooper feels a strong bond with the kids, who look out for him while he teaches them to read. Through a twist of fate, Cooper finds the old man again, and he is able to help his new friends and their mom get back on their feet while he returns to his old home. Cooper’s is a sweet tale of friendship.

Voyage to Shelter Cove, by Ralph da Costa Nunez with Jesse Andrews Ellison; illustrations by Madeline Gerstein Simon (*White Tiger Press, 2006). In an undersea tale that addresses both homelessness and environmental concerns, we meet Serena the seahorse and Herman the hermit crab. The two journey with friends to a place called Shelter Cove when their home reef is threatened by developers. In Shelter Cove, each friend sets and pursues a goal for the future. Voyage to Shelter Cove introduces us to whimsical sea creatures in a fantastical ocean setting. An activity book is available.

The Can Man, by Laura E. Williams; illustrations by Craig Orback (Lee & Low Books, 2010). When Tim wants to save up money for a skateboard, he gets an idea from the clanging sound of the Can Man down the street: he’ll collect cans and cash them in, just like the homeless guy does. But by the time Tim has amassed enough cans to redeem, he has met the Can Man up close, and his perspective has shifted. Laura E. Williams treats her characters with respect and kindness, and readers will be inspired to consider their own preconceptions and to reach out to others.

Saily’s Journey, by Ralph da Costa Nunez with Karina Kwok; illustrations by Madeline Gerstein Simon (*White Tiger Press, 2002). After Saily the snail unexpectedly loses his shell, the resulting adventures with a spider, a seagull, crickets, and other snails make his search for a new home a true hero’s quest. Saily’s Journey incorporates themes of homelessness, bullying, the dangers of the streets, self-acceptance, and the meaning of true friendship. The story is framed in a classroom setting—Saily is a character whom students in the book read about—so there is a set-up for discussion at the conclusion of the book.

A Family of Five or Six, by Pat Van Doren; illustrations by fifth- and sixth-grade students at Carollwood Day School in Tampa, Florida (HEAR US, Inc., 2008). After losing their home in a storm, Michael’s family of six is split: his father is missing and he, his mother, and his three siblings live in a tent, surrounded by other displaced families. While he deals with the realities of homelessness—washing clothes in a shelter on the weekends, using tiny tubes of donated toothpaste, even trying to make a game of “camp out” to fight the sadness of living in a tent—Michael never stops hoping that he’ll find his father and that the family of six will be together again. Students provided the touching illustrations for this novel.

A Place of Our Own, by Pat Van Doren; illustrations by Wanda Platt (HEAR US, Inc., 2008). This is the second story about the life of Susan, the girl from Where Can I Build My Volcano? Now she is older, and she and her mother are moving from the transitional shelter to a place of their own. Susan’s ease with her situation, gratitude for the help she has received, and compassion for the people in the shelter shine through in this satisfying full-circle tale.

For older readers (ages eight and up):

Hold Fast, by Blue Balliett (Scholastic Press, 2013). On the South Side of Chicago, the Pearl family is thrown into a nightmare when the father, Dash, disappears. They face the shelter system during a bitterly cold winter, and 11-year-old Early is determined to find her father, giving the book a mystery element. Hold Fast draws from the critically acclaimed New York Times best-selling author Blue Balliett’s own time spent volunteering in Chicago’s shelters. In this powerful, emotional story filled with rich detail, Early comes up with a solution to homelessness that all kids can work on … maybe even in the real world.

Gracie’s Girl, by Ellen Wittlinger (Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, 2002; published as an e-book, 2012). Bess is starting sixth grade, and this year she wants to stand out and be popular. She resents the time her parents make her spend volunteering at a shelter kitchen and the secondhand clothes that litter her living room when her mother organizes the community rummage sale. But then Ellen meets Gracie, an old woman who is homeless, and her eyes open to issues larger than herself. Ellen Wittlinger’s characters—Bess, her parents, her brother, and her friends—sparkle with humor and humanity. Their voices and actions ring true as Bess discovers compassion within herself.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Databank

Resources

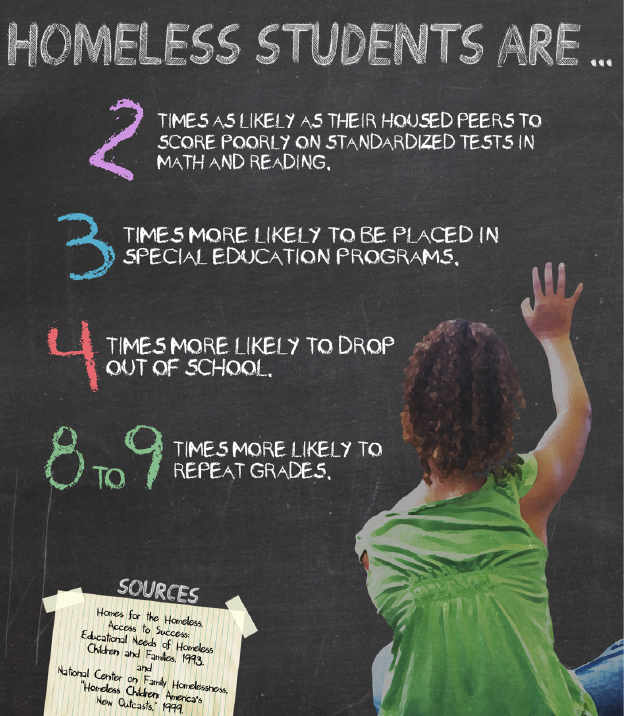

Homes for the Homeless, Access to Success: Educational Needs of Homeless Children and Families, 1993 ■ National Center on Family Homelessness, Homeless Children: America’s New Outcasts, 1999.

To download a pdf of this Databank, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The National Perspective—

Presenting The American Almanac of Family Homelessness

Family homelessness in the United States is a phenomenon of immense proportions, a subject begging many questions whose answers lead to still more questions. For these reasons it is difficult to know where to begin contemplating the topic and how to frame a discussion of homelessness that is comprehensive, illuminating, and rich with ideas for alleviating this large and growing crisis.

But a new report is here to help. The American Almanac of Family Homelessness, newly available from ICPH, divides this monolithic subject into subtopics. Together, the volume’s articles provide a guide that is both specific and all-encompassing.

Who is homeless, and why? The first of the Almanac’s three sections, Issue by Issue, begins with “The Roads Too Often Traveled: Perceived Causes of Family Homelessness.” This article incorporates the findings of city leaders across the country in its breakdown of major causes of homelessness: poverty, unemployment, lack of affordable housing, low pay, domestic violence, mental illness, substance abuse, and the exorbitant costs of medical care. The 20 articles that follow include discussions of the different struggles faced by individual segments of the homeless population, such as minority families, rural families, youth (particularly LGBTQ youth), survivors of domestic violence, and children with learning disabilities.

Where are homeless families? The Almanac’s second section, State by State, has an article devoted to each state and the District of Columbia. The articles offer statistics and other information on homelessness as it exists in particular locations across the country. (For example: on a single night in January 2011, there were 919 people in homeless families in Arkansas, while Colorado had more than ten times that number. The governor-appointed chair of the Delaware Interagency Council on Homelessness also serves as executive director of the Homeless Planning Coalition of Delaware, while Illinois has no governor-appointed individual specifically overseeing efforts to combat homelessness; rather, the state’s Affordable Housing Task Force works to secure lower-cost housing for low-income households, including those who are homeless or at risk of homelessness.)

What is being done to help? Each of the Almanac’s sections addresses this question—Issue by Issue through critiques of the federal government’s approach to combating homelessness, such as the rapid-rehousing initiative, and State by State through its descriptions of regional programs. In addition, the third section, Ideas in Action, turns a spotlight on national, state-level, and local efforts that provide models for reducing homelessness and lessening its negative effects. The “Unique Funding” portion of Ideas in Action lists innovative ways of compensating for reductions in federal funding for anti-homelessness programs; an example is Georgia’s one-time Homeless Opportunity Fund, which generated $22 million for permanent supportive housing through a rental-car tax. “Early Childhood Development Programs” and “After-school Enrichment Programs” both highlight work being done around the country to narrow the educational gap between homeless children and their housed peers.

The American Almanac of Family Homelessness is an invaluable tool for office holders and seekers, homeless advocates, educators, government agencies and nonprofit organizations devoted to ending homelessness, and all others concerned about this issue. It is a starting point for learning about who needs help, what is being done about it, and what we can still do.

To download the Almanac or access an html version, visit our Web site at www.ICPHusa.org. To request a print copy of the Almanac, email info@ICPHusa.org.

Resource

Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, American Almanac of Family Homelessness, 2013.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

About UNCENSORED

Spring 2013, Vol. 4.1

FEATURES

Healthy Beginnings, Healthy Life: The State and Future of Maternal and Child Health Care in the United States

Lives in Transition: Santa Barbara’s Transition House Gives Homeless Families a Path to Independence

EDITORIALS AND COLUMNS

The Historical Perspective—Finding Homes for Poor Children

Not Alone: Children’s Books Spark Discussions about Homelessness

Databank—Doing the Math on Homeless Students

The National Perspective—Announcing The American Almanac of Family Homelessness 2013

Cover: Sarah Gray, a pediatric nurse practitioner student at Emory University’s Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, listens for wheezing during a clinic rotation.

50 Cooper Square, New York, NY 10003

T 212.358.8086 F 212.358.8090

Publisher Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD

Editors Linda Bazerjian

Assistant Editor Clifford Thompson

Art Director Alice Fisk MacKenzie

Editorial Staff Sara Johnsen, Kate Slininger, Ethan G. Sribnick

Contributors Lee Erica Elder, Melissa Walker, Carol Ward

UNCENSORED is published by the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH). ICPH is an independent, New York City-based public policy organization that works on the issues of poverty and family homelessness. Please visit our website for more information: www.ICPHusa.org. Copyright ©2013. All rights reserved. No portion or portions of this publication may be reprinted without the express permission of the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness.

Letters to the Editor: We welcome letters, articles, press releases, ideas, and submissions. Please send them to info@ICPHusa.org. Visit our website to download or order publications and to sign up for our mailing list: www.ICPHusa.org.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness or its affiliates.

![]() ICPH_homeless

ICPH_homeless

![]() InstituteforChildrenandPoverty

InstituteforChildrenandPoverty

![]() icph_usa

icph_usa

![]() ICPHusa

ICPHusa