Publisher’s Note

Dear Reader,

With the Summer 2012 issue of UNCENSORED, we continue to investigate subjects related to family poverty and homelessness in articles we think you will find enlightening.

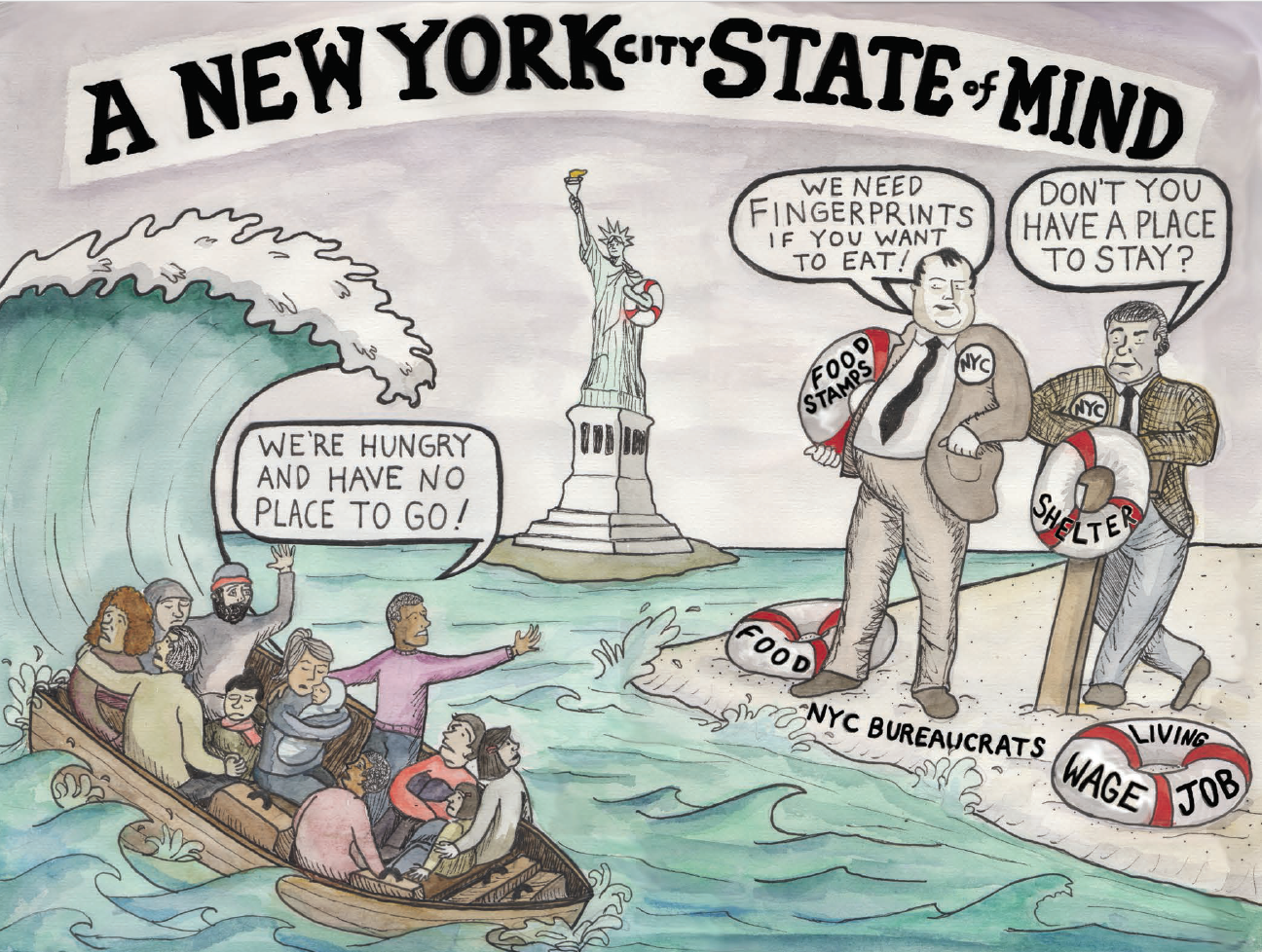

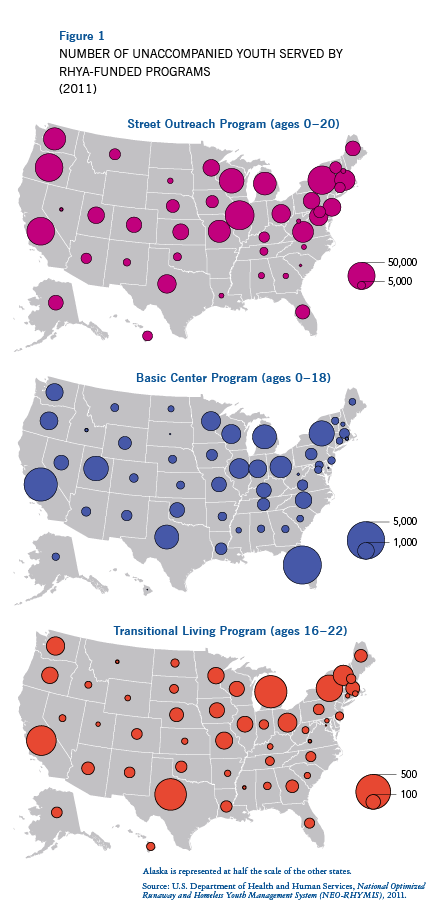

This issue’s National Perspective piece, in our On the Homefront section, looks at homeless youth and the need for better data to help understand and target services toward this very vulnerable group. One of our features focuses on the plight of undocumented families in the U.S., who often face the hardships of poverty without the public resources needed to weather it. Another reveals the current bureaucratic and political challenges to receiving food stamps during tough economic times. Our feature on horticultural therapy explores the positive effects of gardening on poor and formerly homeless individuals, who benefit from healthy food, learn life lessons, form stronger relationships with their caregivers, and take pride in and ownership of the process.

Finally, this issue’s Historical Perspective essay takes a look at decades of public housing in New York City and the debates over who should reside there, an issue with relevance for the present day.

As UNCENSORED reports on the struggles of poor families and what is being done to help them, we are grateful to those who have followed our coverage, and we welcome comments, questions, and suggestions at info@ICPHusa.org—as well as new readers.

Sincerely,

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, Publisher

President and CEO, Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

To download a pdf of this cartoon, click here.

Reaching into the Shadows:

Navigating the Intricacies of Serving Undocumented Families

by Carol Ward

Early in the summer of 2012, a cover story in Time magazine featured a group of young people who have “come out” in a new way. These individuals, brought to the United States as small children, were openly declaring their status as non-citizens via social media and other outlets in an effort to effect political change. Whether or not as a result, President Obama announced in June 2012 that hundreds of thousands of people who immigrated to the U.S. illegally as children will be allowed to stay and work without fear of being deported.

Such developments have fueled the debate about immigration in the United States, but these stories don’t capture the realities of the lives of undocumented people living in this country—a group that the Center for Immigration Studies numbered in 2009 at nearly 11 million. Many are concentrated in specific areas, with, for example, 2.7 million in California, 1.45 million in Texas, 1.05 million in Florida, and 925,000 in New York, according to the Pew Research Center; approximately 80 percent are from Latin American countries (the majority of those from Mexico), 12 percent from Asia, 4 percent from Europe and Canada, and 4 percent from Africa and other places. They come to the U.S. for reasons ranging from extreme poverty to political oppression in their native countries; once here, many have a tenuous personal safety net at best.

The Center for Immigration Studies estimates that nearly 11 million people in the United States are undocumented.

“Undocumented families are among the most resourceless population in the United States,” says Ruben Garcia, director of El Paso’s Annunciation House, a privately funded shelter and assistance center that serves mainly undocumented individuals.

“These families are unable to access the most basic of social services that we usually count on to help people keep their heads above water,” Garcia adds. “That makes life very difficult and marginalizes people in a severe way.”

Susan Bowyer, directing attorney for the Immigration Center for Women and Children’s San Francisco office, calls undocumented individuals “the most vulnerable people in the United States.”

“They can’t call the police or access services, and they’re not eligible for any public benefits,” Bowyer points out.

That inability to access public services is exacerbated by the other significant problems that undocumented individuals typically face, including threat of deportation, barriers to working legally, and being barred from low-income housing. In addition, they are often hesitant to seek medical care or ask for help in school for fear of drawing attention to their families’ illegal status.

The agencies that exist to help the poor in this country are often stymied in their efforts to assist undocumented individuals and families, due to restrictive or confusing laws governing who is eligible for help. Yet there are strategies that service providers can use to best meet the needs of undocumented clients. The first step is outreach.

Ask? Don’t Ask?

Experts in the field say that there are programs to address many of the crises that befall undocumented families—including homelessness and lack of food—on an alarmingly regular basis. But many of these families are loath to be found out, or to give any information that might reveal their undocumented status.

Eliana Kaimowitz, an attorney and equal justice works fellow for the California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation, maintains that having that information is crucial to determine the most efficient way to help.

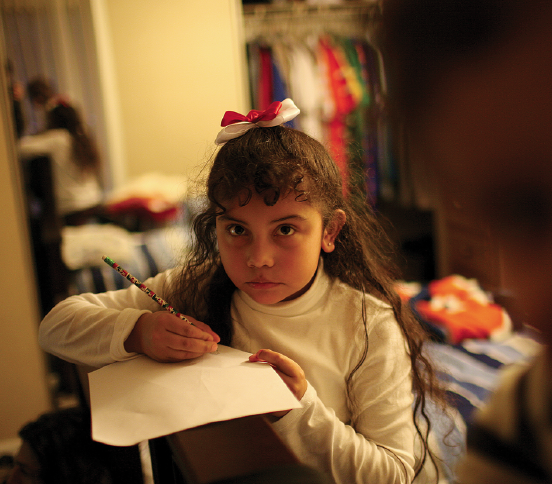

A strict immigration law in Alabama, HB-56, requires police, schools, and hospitals to check the immigration status of students, patients, and anyone stopped and suspected of being an undocumented immigrant. The law has both the legal and undocumented Latino population in the state fearful of deportation and family breakups. A young girl does her homework in a home of mixed citizenship. Half the family is worried about sudden deportation, while others, born in the U.S., have full citizenship.

“It’s really hard to help people if you don’t know what’s going on,” Kaimowitz says. “It’s important to let people know that immigration status won’t preclude you from helping them, but it may help clarify what type of help you can give them.” She suggests assuring clients that the service provider “has an obligation not to disclose” the information with others.

“Not asking about it just further perpetuates the undergroundness of it all,” Kaimowitz adds. “What’s really terrible is that so many families are eligible for services but they’re not getting them.” She points to mixed-status families, in which one or more members are U.S. citizens while others are not, as a key example.

Others say asking about immigration status creates an unnecessary barrier to services.

“It’s clear that nonprofits, under federal law, don’t have an obligation to ask about immigration status,” in the view of Meliah Schultzman, an attorney with the National Housing Law Project. She notes that immigration status does not come down to simply being documented or undocumented—that there are many categories in between. There is considerable confusion at the provider level about which programs are applicable for undocumented families or families whose status is between illegal and legal, meaning that questions about status may not always be helpful to ask.

“As a policy it would be very helpful if a nonprofit provider made it clear from the outset that they do not need to know about immigration status and are not going to ask about it,” Schultzman says.

“Even though immigration is such a hot topic, most social workers don’t know anything about how it works and what the different statuses are,” according to Kaimowitz. “It’s more complicated than just having a green card or being undocumented. There are different statuses that make you eligible for different types of assistance, and people don’t know that.

“A lot of the social workers are really overworked so they don’t have time to ask their supervisor, they just say ‘no, you’re ineligible’,” Kaimowitz adds. “It’s more work and in some situations there is no guidance.”

Bowyer’s agency works to get documentation for illegal immigrants who meet certain criteria. One example is those who have applied for U Visas. Created by the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000, U Visas are designed to provide lawful status to noncitizen crime victims who are assisting or are willing to assist legal authorities with investigations. U Visa status may be available to victims of domestic violence or certain other crimes.

In some states, including New York and California, public benefits are available for U Visa applicants, Bowyer says.

“The problem is that front-end workers don’t understand the law—a woman applies for services but they are denied because the social worker tells her she needs a social security number,” Bowyer says, noting that her agency has started a major effort to educate providers with regard to this issue.

Mixed-Status Families

The extent to which mixed-status families can access services is an important, and too often misunderstood, issue.

El Centro, a Kansas City, Kansas–based outreach organization that focuses on the Latino community, provides myriad services for both documented and undocumented families in the area. Melinda Lewis, public-policy consultant for El Centro, claims that most undocumented families are of mixed status, with one or more children having citizenship.

A worker assists a Mexican family with immigration paperwork in her Garden City, Kansas, office. Her clients range from completely undocumented residents to those seeking to visit their home countries and needing the proper paperwork to return to the United States legally.

Fear among this group runs high, according to Lewis, making it difficult to provide any assistance. “We have many, many immigrant parents who won’t apply for food assistance for their children,” she says. “They won’t believe us when we say they are in fact eligible because they are afraid of discriminatory action, or even afraid of adverse immigration action.”

That same problem manifests itself in different ways across the country when it comes to housing issues, Schultzman says. She notes the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development rule that households cannot be rejected for low-income housing because they have one or more undocumented members; the assistance level is based on the number of documented individuals.

Schultzman points out, however, that housing authorities do not typically understand the nuances of the rules, so it is incumbent on local service providers to know.

“Many housing authorities still have forms that say every household member must provide a social security number,” Schultzman says as an example. “That automatically turns a lot of families off who otherwise might be eligible for mixed-household status.”

Schultzman says that she understands the immigrants’ fear of being exposed if they reveal their status—but that she has not encountered any situations in which undocumented occupants have been reported.

In the Trenches

Many efforts to help noncitizen residents can get mired in the details of who legally qualifies for what services and, equally important, how to convey the intricacies of the law to overworked providers and disenfranchised immigrant families. But out in the trenches, service providers are coming up with ways to help undocumented families gain a footing in this country.

For 34 years Annunciation House has been helping undocumented individuals who cross the border into Texas, with Garcia estimating that the shelter has hosted nearly 120,000 undocumented people during that time.

Volunteers prepare bags of food that will be distributed at the Community Posada to support immigrant families who are struggling in the challenging Arizona economy—one made more difficult by the new laws regarding the employment of undocumented workers.

The organization’s main role is to provide temporary shelter for those who need to regroup before making their way in a new country. Garcia says the challenges for such people are huge.

“It’s very difficult for people to exit shelters,” he says. “They have a very hard time finding work, and if they do find it, it’s very low pay or they find themselves in situations where the employer doesn’t pay what he promised.” Annunciation House does not have a strict time limit for stays, but guests are encouraged to move through in order to make room for the next wave of people in need.

Annunciation House also helps facilitate employment, but not in the usual way.

“You basically have to set up an informal network” outside the government-supported or privately funded employment programs within shelters and other facilities, Garcia says. “Undocumented workers seek employment in the informal economy. They inquire at places where they see other people working, things like that.”

Affordable housing is also an issue. Garcia says many landlords in the El Paso area are not interested in potential tenants’ legal status; they mainly want to know if the tenants can pay rent. He adds, “These are substandard apartments that rent by word of mouth, and the poor know how to find them.”

Even amidst uncertainty and fear, undocumented families try to maintain family life and networks in the U.S.

Up in the Seattle area, Gina Custer, director of housing services for East King and South King Counties at the YWCA Seattle/King/Snohomish, encounters undocumented families on a regular basis.

The YWCA inquires about the status of those seeking assistance, but only to ascertain the correct course of action, Custer says. Once people are placed in the organization’s temporary or transitional housing, other services come to the fore.

“We can’t do a lot with employment,” Custer admits. “Some folks are completely amazing in that somehow they are able to get jobs without social security numbers but they’ve gotten tax identification numbers. It’s really hit and miss, to be honest.”

Custer says, however, that she can connect clients with legal services that may be able to help with immigration issues, and to other services, such as language classes. Custer also notes that interpreters are provided for women or families who need them during intake and throughout their stays. One of the main jobs for Karly Garcia (no relation to Ruben Garcia), a Latina Outreach Specialist for the YWCA Seattle/King/Snohomish, is to help Spanish-speaking immigrants navigate unfamiliar bureaucratic processes.

In addition, Karly Garcia troubleshoots a variety of other challenges faced by undocumented women and families. She provides health education to the Latina women who utilize the YWCA facilities, about 80 to 90 percent of whom are undocumented, she estimates.

But more than that, she works as a liaison and advocate for these women, who often do not have the means or the knowledge base to access the services they need. Those needs run the gamut, from emergency dental care to surgery to help for a schizophrenic son.

“There are so many challenges just on a day-to-day basis, and they don’t know where to turn,” Karly Garcia says. “They don’t understand the language or the system,” and they have fewer service options due to their undocumented status.

Garcia’s view is simple: “They are already here, we need to help them.”

Murky Waters in Alabama

Finding ways to reach and assist undocumented families in Alabama became more difficult last year, when the state legislature passed what is considered to be the most aggressive anti-immigration law among all states, surpassing even the restrictions of Arizona’s law.

Four other states (Utah, Georgia, Indiana, and South Carolina) have passed immigration-enforcement laws, while eight more (Oklahoma, Missouri, Mississippi, Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, North Carolina, and Florida) have made moves toward doing so. Among other restrictions, Arizona’s SB 1070, passed in 2010, made it a misdemeanor for an alien to be in Arizona without carrying the required documents; it also required that state law-enforcement officials attempt to determine individuals’ immigration status during lawful stops, detentions, or arrests, or during “ lawful contacts,” when there is reasonable suspicion that the individual is an illegal immigrant. (The U.S. Supreme Court struck down parts of the law in June 2012.) In Alabama “we took Arizona’s bad law and made it worse,” says Stephen Stetson, a policy analyst at the Arise Citizens’ Policy Project, a Montgomery, Alabama–based group that addresses poverty issues in the state.

Alabama’s new law instructs police to check the immigration status of anyone they stop if they suspect the person of being an undocumented immigrant. The law also makes it a felony to harbor, shield, or transport illegal immigrants, although it is unclear where the burden of knowledge lies. In October 2011 the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals temporarily blocked several portions of the law, including a requirement that schools check the immigration status of new students and their families.

Stetson says the law has put a severe crimp in the services available to undocumented individuals, such as access to housing.

“To rent an apartment to someone who is undocumented is criminalized in Alabama,” he says, noting that landlords are handling the new rules in various ways.

“The law doesn’t say that [the landlord] must demand citizenship papers, but he could,” Stetson explains. “A lot of landlords are erring on the side of caution. It’s been extremely hard for a lot of these people to enter into lease agreements.”

An early version of the law, which has since been amended, was interpreted to mean that state-run utility companies could not enter into business transactions with undocumented individuals. For the winter of 2011–12, that meant many undocumented families were without heat and running water.

Providing food assistance has also become fraught with difficulty. Dick Hiatt, executive director of the Food Bank of North Alabama in Huntsville, says excessive paperwork, fears of prosecution, and lower food volume are three results of the new law.

The Food Bank of North Alabama serves as a wholesaler, distributing food—including government food provided through The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP)—to several groups throughout the region. Because it receives that food from the federal government, it is considered to be a state-funded entity. Under the new law, the Food Bank of North Alabama must prove that no group it conducts business with employs any illegal immigrants.

“It all has to be done formally, and all the documents have to be notarized,” Hiatt says, noting that his organization is audited regularly.

For the rural churches and groups that rely on the food bank, this level of bureaucracy is daunting.

“It’s very confusing for a lot of these small organizations,” Hiatt says, adding that several are noncompliant. “We have to place them on hold until they can get their paperwork done. Their whole mission is to feed hungry people, and this has made trying to help people in need much more difficult.”

The challenges do not end there. According to Hiatt, the new law requires that if any agency is providing assistance based on any criteria—such as means testing—then that agency must determine if the person receiving the food is an American citizen.

An obvious way around that problem would be to eliminate the means testing, which would then exempt the agency from inquiring about immigration status—except that under federal law, food provided through the TEFAP program requires such testing.

“The problem is that without federal food there isn’t much food available,” says Hiatt. “Ever since the economy went south it’s been federal food that has held us together.” That problem has been made worse by the diminished farming in Alabama—due to a lack of migrant labor under the new rules—which means food banks can no longer rely on “community food security” programs, as they did in the past.

The solution is less than ideal. “Many of the food banks are just getting everybody they serve to sign a statement saying they are a U.S. citizen, regardless of the reality, and that gets [the food bank] off the hook,” Hiatt says, adding, “It’s just gotten insane down at the distribution level.”

Resources

Pew Research Center; Washington, DC ■ National Housing Law Project; San Francisco, CA ■ California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation; Sacramento, CA ■ Annunciation House; El Paso, TX ■ Immigration Center for Women and Children; Los Angeles, CA ■ El Centro; Kansas City, KS ■ New York Times; New York, NY ■ Food Bank of North Alabama; Huntsville, AL.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Little Becoming Less:

States Enact Changes in Efforts to Curb SNAP Benefits

by Carol Ward

Mary, a 40-year-old mother of three, has fallen into poverty over the past two years. The San Diego resident was once middle-class, with a husband who had a secure job and a good income. But divorce, job loss, and other factors, including her ex-husband’s financial recklessness, have plunged Mary—who received food stamps briefly in the early 1990s—into a realm she never thought she would see again.

“I certainly didn’t expect all this to come crashing down,” says Mary, who recently completed her college degree in social work and is actively searching for a job related to her field. “But right now I have no income and no support.”

Mary turned again to food stamps, initially trying the SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) call line, operated by San Diego County’s Health and Human Services Agency. But several efforts produced no results; her calls were disconnected or placed on hold “forever,” and she was never able to get help from anyone via telephone. Luckily, the computer-savvy Mary was able to apply online and began receiving her benefits within days.

Mary is one of the millions of people, largely victims of the Great Recession, who have joined the food-stamp rolls in the past few years. Enrollment in the program has risen to about 46 million, up by 20 million recipients from five years ago. Annual spending for SNAP is at nearly $80 billion.

As the need for food stamps has expanded, so have bureaucratic barriers to obtaining them—and so, too, have efforts at both the state and federal levels to curb SNAP benefit outlays. From a new assessment of assets for recipients in Pennsylvania, to a recalculation of benefits for some families in Kansas, to proposed drug testing of recipients in Florida and several other states, many legislators are intent on trimming costs and, in some cases, making sure recipients are truly “worthy” of the benefit.

An even bigger threat is developing at the federal level. In summer 2012, several legislators, led by representative Paul Ryan of Wisconsin, were calling for significant cuts to the program, citing the need to lower the federal deficit. At press time, the cuts were being debated in Congress.

A Program That Works … to an Extent

Against that backdrop, poverty continues to threaten the well-being of families, including an estimated 16.4 million children, across the country. The SNAP program is designed to provide a supplemental food source to those most in need; an April 2012 report from the U.S. Department of Agriculture shows that the program has a significant and positive effect on those struggling to put food on the table.

According to the report, Alleviating Poverty in the United States—The Critical Role of SNAP Benefits, SNAP has a stronger effect on the depth and severity of poverty than on its prevalence; that is, while SNAP has had limited success at reducing the number of poor people, it has been able to lower the level of those people’s poverty. The program is particularly effective, the report found, at minimizing poverty among children.

Families participate in a local festival that provides information and resources like fresh, free produce to help families put enough food on the table.

“When SNAP benefits are included in family income, the average annual decline from 2000 to 2009 in the depth [or average level] of child poverty was 15.5 percent and the average annual decline in the severity [or worst cases] of child poverty was 21.3 percent,” the study revealed.

Still, current benefits often fall short of what families need, many advocates say, especially when nutrition guidelines are taken into account. In fact, a 2011 report, The Real Cost of a Healthy Diet, prepared jointly by the Center for Hunger-Free Communities, Children’s HealthWatch, and Drexel University’s School of Public Health, examined whether a healthy diet could be maintained by low-income families in Philadelphia who received the maximum SNAP benefit and shopped at neighborhood food stores.

The USDA’s Thrifty Food Plan, the national standard for a “nutritious diet at a minimal cost,” was cited in the study—which found that the plan is unaffordable for SNAP beneficiaries.

“A family of four who receives the maximum SNAP benefit would need to spend an additional $2,352 per year on average to purchase the Thrifty Food Plan market basket items,” the study concluded.

Limiting Access

An equally challenging aspect of the SNAP program is inaccessibility, whether because of tightened eligibility guidelines, overwhelmed staff, or a bewildering application process.

One of the biggest upheavals within the program at the state level is the reintroduction of asset testing in Pennsylvania.

The asset test, instituted on May 1 of this year, denies food stamps to anyone under the age of 60 with assets worth more than $5,500. The threshold climbs to $9,000 for households with members who are aged 60 and older or disabled. The rules pertain to cash, stocks, and bonds but exclude pension plans, retirement accounts, home values, or life insurance. The Pennsylvania Department of Public Welfare (DPW) projects that the new rules will affect about 2 percent of the roughly 1.8 million people receiving food stamps in the state.

Service providers in Pennsylvania, though, predict that the consequences will likely be more dire than that.

Laura Tobin Goddard, executive director of the Pennsylvania Hunger Action Center, says the new rules will turn some eligible applicants away.

“Many people really don’t like to provide their banking information and may view it as an invasion of privacy,” Tobin Goddard says. “We feel it’s going to turn people away from the program and to food banks and food pantries more than ever, and food pantries are already at their limits.”

Adam MacGregor, communications coordinator for Pittsburgh’s Just Harvest—which helps low-income people access government services—says that the new rules require extra, painstaking work from the clients, the county’s case workers, and go-between organizations like his own.

“It’s actually very difficult and time-consuming to apply for a lot of these programs,” MacGregor says. “If you don’t have the documentation that is required, and if you don’t have your affairs in order, then it’s difficult to get them in order quickly to apply for food stamps you need now.”

MacGregor notes that nearly 40 percent of cases are rejected due to improper documentation. He blames inadequate case-worker staffing and onerous requirements.

“Poverty is such a complex thing, and even missing a phone call or not having a reliable place to pick up your mail can spell disaster for people who are seeking help under the food-stamp program,” MacGregor says.

Joy, a mother of three in Pennsylvania, experienced first-hand the difficulties in navigating the DPW bureaucracy when she applied for food stamps a few years ago. She recalls filing three separate applications, making several phone calls, and waiting more than two months for her benefits to start. “I was really disappointed with the system,” she says. After encountering still more problems, Joy approached Just Harvest to help secure longer-term SNAP benefits.

According to MacGregor, early indications are that there is not a huge number of people being kicked out of the program because of their assets. (Of course, the asset test just went into effect on May 1, and client data are reviewed at six-month intervals.) “The real issue is the deterrent effect of the new asset rules,” he says.

Becky Abrams, director of the Squirrel Hill Community Food Pantry and SOS Pittsburgh, expects negative consequences for her program, which is run by the Jewish Family & Children’s Service of Pittsburgh.

“We’re briefed and ready for the asset-test impact,” Abrams says. “We think it will mainly impact our kosher family clients. It’s very expensive to keep your house strictly kosher. If these families are deemed ineligible for SNAP they might come to rely on our program solely to meet their kosher-food needs beyond what they can provide.

“I think I’m going to be purchasing more food, because I’m determined not to turn people away,” Abrams adds.

A mother holds her three-week-old daughter at a local Department of Human Services office in Oklahoma. The single mom with two children has received food assistance intermittently since her first child was born, two years ago. A high school graduate, she works part-time building websites for a manufacturing company and aspires to become a nurse, but in the meantime she needs food stamps to get by.

Kansas is also among the states that have adopted more stringent requirements for qualification for SNAP benefits. Earlier this year the Kansas Department of Social and Rehabilitation Services changed the way it calculates SNAP eligibility. The new rules apply to mixed-status families, in which one or more members are undocumented.

Under the previous method, only a portion of the household income was counted for those families. For example, if a family of five earned $2,000 a month, and the three children were U.S. citizens but the parents were not, the income would be divided among the five family members. As a result the children would be treated as a family of three earning $1,200 a month. The new rules simply do not count the noncitizen family members, thus determining that the three children earn $2,000 a month—and are no longer eligible for benefits.

Shannon Cotsoradis, president and CEO of Kansas Action for Children, estimates that 2,000 Kansas children who are U.S. citizens have lost access to food stamps because of the change, and that many others have seen benefits reduced. “It’s much more difficult for us to capture how many families are impacted by a reduction in benefits, but the number is significant,” she says.

Cotsoradis describes the “climate of anti-social services” in Kansas, adding, “There have been a lot of policy changes that don’t need legislative approval and the results have been to reduce the level of benefits for families.”

Such reductions have had a significant effect on Latino families, according to Melinda Lewis, public-policy consultant for El Centro, a Kansas City, Kansas–based outreach organization that focuses on the Latino community.

“We have cases where women have gone back to their abusers because they can’t afford to feed their kids due to the loss of those benefits,” Lewis laments. “We have individuals who are making very tough decisions about the nutritional quality of the food they buy their kids. They’re making decisions about whether to pay their utility bill or buy food, they’re doubling up in households.”

Lewis blames the “hostile climate” generated by the state for newfound fears among immigrant communities that identification and deportation of undocumented people will expand.

“It has really undone years if not decades of work that immigrant-serving organizations like ours have done to build trust with parents and help them understand that their citizen children are eligible for the same benefits that other citizen children can receive,” Lewis points out. “We fear that the ramifications of the severing of the trust between the state and these families will last for years to come.”

Other states have enacted or are considering a variety of measures designed to curb use of food stamps. This year, 28 states have considered requiring drug tests for all recipients of public benefits. Florida passed that measure in 2011, though a lawsuit brought by the American Civil Liberties Union has made the law’s implementation uncertain. It seems likely that threats to food-stamp benefits will continue, and perhaps expand, as states grapple more and more with budget deficits.

Calls Unanswered

While some states have taken no formal action to restrict SNAP benefits, even existing programs are sometimes dysfunctional.

Mary, the mom in San Diego, did not have an unusual experience when her calls to the food-stamp hotline went unanswered, according to Joni Halpern, director of the Supportive Parents Information Network, a group that helps families through the application process.

A woman pieces together the weekly groceries for her family from free items at the local food bank, SNAP benefits, and wages.

“In situations where organizations help the family by shepherding the application through, things are getting better,” Halpern says. “But if a person just goes to the office or makes a call, I wish them a lot of luck. It’s not going to be easy.”

Halpern says the county’s Health and Human Services Agency (HHSA), which administers SNAP benefits, has seen a significant scaling back in staffing in recent years, to the point where “they’re not even in the neighborhood of keeping up.” She also criticizes the agency’s application-processing methods, which allow any caseworker to access any application, rather than having individual workers assigned to individual cases, making for confusion and ineffectiveness.

“We’re seeing more and more people who can’t get through the process because their documents were transferred and no one knows where they are,” she says. “The workers are unable to keep up. It becomes completely happenstance if a mistake gets corrected.”

That is, of course, if the applicant ever gets that far into the process. An internal HHSA report prepared by InTelegy, a call-center consulting firm, reportedly revealed that 350,000 calls to the food-stamp line—about five-sixths of total call volume—went unanswered. For those callers who got through, the average wait was approximately 30 minutes. The study blamed lack of workers and an inadequate number of phone lines.

In Florida, Sari Vatske, director of partner services for Feeding South Florida, reveals that her agency’s clients have encountered similar obstacles.

“We’re seeing an increase in the number of applicants and an increase in barriers to access,” Vatske says. “A lot of it has to do with budget cuts at DCF [Florida’s Department of Children and Families]. Their call centers are receiving 5,000 calls by 2 p.m. The people who can’t apply by computer are feeling very frustrated.”

In partnership with one or more other agencies, Feeding South Florida is in the planning stages of operating a call-processing center to help deal with the overflow and get more people enrolled.

“In Florida there is a lot of money that’s not being drawn against, but it’s because people can’t call in because the lines are busy and they just eventually give up,” Vatske explains.

In late 2010 Lowcountry Food Bank in Charleston, South Carolina, launched a “Benefit Bank” SNAP-outreach program in response to low usage of food stamps, according to president and CEO Pat Walker. Benefit Bank is an online software tool that conducts pre-screening for potential clients and helps them organize all needed paperwork.

Walker says the move was in response to findings from a study, conducted by his organization in partnership with Feeding America and Mathematica Policy Research, showing that only 34 percent of the Lowcountry Food Bank’s clients were SNAP recipients.

“For those who have never applied for SNAP, the study showed that a significant portion either thought they were ineligible, although they had incomes below the 130 percent of poverty threshold, or they were turned off by the inconvenient process,” Walker says, noting that problems have been compounded in recent years due to layoffs at the state level.

These stories suggest that while the SNAP program is helping, there are still many obstacles to full usage.

“All the obstacles take a toll on people’s dignity, they take a toll on their peace of mind, and poor people have very little peace of mind to begin with,” says MacGregor of Just Harvest. “The people enacting these laws need to have some empathy. Demand for help is up for a reason—people need help.”

Resources

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; Washington, DC ■ U.S. Department of Agriculture; Washington, DC ■ The Center for Hunger-Free Communities, Children’s HealthWatch, and Drexel University’s School of Public Health; ■ Coalition Against Hunger; Philadelphia, PA ■ Pennsylvania Hunger Action Center; Enola, PA ■ Just Harvest; Pittsburgh, PA ■ Squirrel Hill Food Pantry; Pittsburgh, PA ■ Kansas Action for Children; Topeka, KS ■ Supportive Parents Information Network; San Diego, CA ■ Feeding South Florida; Pembroke Park, FL ■ Lowcountry Food Bank; Charleston, SC.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Green Thumbs Up:

Working with Nature Provides a Fresh Start for Homeless and Once-Homeless Families and Adults

by Lee Erica Elder

Plants begin from seed and must often be uprooted and transplanted to grow deep roots, to become strong, to survive and thrive. The nature of gardening is transient, and these acts of transition and growth have become a metaphor for programs around the country using gardening and farming to create stability in the lives of homeless and transient families.

As seen in our Spring 2012 cover story, “Grass Roots: Innovative Food Education Programs,” the green-food and nutrition-education movements are booming nationwide. In addition to using agriculture to educate communities about nutrition, organizations find that the very act of communing with nature, especially in urban spaces, improves the mental health, physical well-being, and quality of living for the homeless, residents of low-income communities, and those in supportive housing. Participants learn coping skills and survival mechanisms and witness real-life lessons in accepting change during times of transition.

Residents of a New York City supportive-housing facility, The Bridge, work together pruning a tree as part of the horticultural-therapy program on site.

In February 2012 a consortium of health and housing advocates convened at the Sixth Annual Horticultural Therapy Forum, sponsored by The Horticultural Society of New York (The Hort), to discuss the role and merits of horticultural therapy (HT) in providing viable supportive housing for families and adults. Most of the organizations represented at the forum belonged to the Supportive Housing Network of New York (The Network), which was founded in 1988 and comprises more than 200 providers of supportive housing in New York—home to more than 43,000 such units. People from The Network, The Bridge, United Way of New York City (UWNYC), Praxis Housing Initiatives, and The Hort’s own HT programs, among many others, spoke about their experiences with horticultural therapy in supportive-housing settings. As defined by The Hort’s event literature, horticultural therapy is “an effective cognitive behavioral therapy” that provides benefits including “improved indoor air quality, access to healthy food, and a stronger sense of community connection. For a number of Network members, the benefits of providing HT to their tenants have been immediate, substantive and tangible—tenants receive great pleasure from the flowers, plants, fresh food and herbs they’ve helped nurture and grow.”

Inspired by the stories shared at the event, UNCENSORED wanted to explore the ways in which horticultural therapy can effect positive change in the lives of homeless and formerly homeless individuals and families and those in supportive housing and other, similar environments.

Defining the Practices

While horticultural therapy developed relatively recently as a field, it is not a new idea. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and a prominent physician, noted that working in gardens greatly benefited the mentally ill. HT training was first offered to professional therapists near the end of World War I in the occupational-therapy department of Bloomingdale Hospital, in White Plains, New York, and rehabilitation of hospitalized war veterans during the 1940s and ’50s involved HT to a significant degree. The first HT text, Therapy through Horticulture, by Alice Burlingame and Dr. Donald Watson, appeared in 1960.

What are the differences between horticultural therapy and therapeutic horticulture, and where does vocational horticulture fit in? The American Horticultural Therapy Association (AHTA) provides a few working definitions in its 2007 Positions Paper:

Horticultural Therapy Horticultural therapy is the engagement of a client in horticultural activities facilitated by a trained therapist to achieve specific and documented treatment goals. AHTA believes that horticultural therapy is an active process which occurs in the context of an established treatment plan where the process itself is considered the therapeutic activity rather than the end product.

Therapeutic Horticulture Therapeutic horticulture is a process that uses plants and plant-related activities through which participants strive to improve their well being through active or passive involvement. In a therapeutic horticulture program, goals are not clinically defined and documented but the leader will have training in the use of horticulture as a medium for human well-being.

Vocational Horticulture A vocational horticulture program, which is often a major component of a horticultural therapy program, focuses on providing training that enables individuals to work in the horticulture industry professionally, either independently or semi-independently. These individuals may or may not have some type of disability.

Programs around the country use these methods to help residents of low-income communities as well as the homeless. “I think the value is engaging in a rewarding, nonthreatening activity with a living thing, in this case plants, that pass no judgment, and mirror the diversity, adversity, and demands of life,” says Leigh Anne Starling, a registered horticultural therapist serving on the board of directors of the AHTA.

Starling has worked with the Homeless Garden Project (HGP) in Santa Cruz, California, which provides sanctuary, job training, transitional employment, and support services to the homeless. “Our programs take place in a three-acre organic farm and related enterprises. We also have an active volunteer and education program that served nearly 1,200 diverse people in 2011,” says Darrie Ganzhorn, HGP’s executive director. “HGP’s programs exist at the intersection of urban agriculture and food-justice movements, transitional jobs and job training, homeless services and therapeutic horticulture. There is a synergy among these purposes and ideals in daily practice at the farm.” In her time at HGP, Starling found that the therapeutic environment gave participants a sense of both self and community. “Folks who participate in the HGP gain self-esteem, self-confidence, self-awareness, and independence through learning about plants and the cycles of the garden (cycles of life), being responsible for a living entity that provides a basic necessity of life—food, and through cooperative efforts successfully achieve common goals. Additional benefits of working with the HGP and in the garden include communication skills, problem-solving skills, work skills and behaviors.”

Georgia’s Place, a residence for formerly homeless individuals in Brooklyn, N.Y., has a rooftop farm where residents take ownership of the gardening process.

Gateway Greening in St. Louis, Missouri, is an organization dedicated to educating and strengthening communities through gardening and urban agriculture, supporting more than 220 community and school gardens throughout St. Louis. In addition, its City Seeds Urban Farm provides both therapeutic-horticulture and vocational-training programs. In partnership with St. Patrick Center, a local provider of homeless services, the therapeutic program, called Shamrock, gives participants the opportunity to observe an entire growing season and, consequently, to learn the arts of patience and leadership. The programs rely heavily on volunteers, whom the therapeutic clients have the opportunity to lead. Says Annie Mayrose, the City Seeds urban-agriculture manager, “It’s a good leadership experience for them, as well as confidence building, so they can teach what they know. They get to decide what to plant and where it’s going. We have some personal beds as maintained exclusively by the therapeutic group and that food goes exclusively to those clients.”

Matthew Wichrowski, MSW and HTR (horticultural therapist registered), a horticultural-therapy practitioner and board member of AHTA, says that horticultural therapy “has the potential to impact many areas of human function and can meet the needs of people having significant medical and psychological challenges, to those seeking wellness and improved quality of life.” He sees specific benefits for families with children. “Horticultural therapy can impact children and families facing financial and housing challenges in many ways,” Wichrowski says. “We use ‘eat and plant’ activities to explore where food comes from and fun ways to eat healthily. Children in today’s society experience a disconnect between what they eat, how it gets there, and the impact of diet on their health. Although HT techniques employ a wide array of gardening activities to achieve therapeutic results, ‘eat and plant’ activities are a unique way to explore nutrition. HT activities provide a little exercise, and can be structured to enhance and reinforce school curriculums. The garden also becomes a place of community where social activities improve. A colleague of mine used garden activities to promote literacy by reinforcing reading skills and having mothers read to their children in the garden setting.”

In New York City, The Bridge, Inc.’s horticulture program provides clients with job training and paid employment. The program began in 2005 with the creation a roof deck at the group’s headquarters on Manhattan’s Upper West Side and a grant from the Burpee Foundation to develop a horticulture-training program for clients in partnership with the Horticultural Society of New York. The Bridge has since secured (figuratively speaking) seed grants from UWNYC through the New York State Department of Health’s HPNAP (Hunger Prevention and Nutrition Assistance Program) to start a number of urban farms in connection with its residences; it currently operates farms at three locations. “We work with people with serious mental illness, substance-abuse issues, and HIV/AIDS who are homeless, coming out of psychiatric hospitals, and jail/prison,” says Carole Gordon, director of housing development at The Bridge. “Many also have serious health conditions such as obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, etc., and do not lead healthy lifestyles.” The opportunity to eat a diet of fresh vegetables and receive nutrition and cooking education through the horticultural program has made a vast difference in client health. Gordon’s goal is to create an urban farm at every new residence that is developed; in the next three years, she hopes to build five new farms to benefit homeless adults with serious mental illness, including veterans, young adults (18–24) referred from state treatment facilities and foster care, and low-income families, among them veteran families with children. “Bridge clients learn many skills through participation in the horticulture program,” she says. “These include physical and coordination skills and exercise, working together as a team to grow produce, farming, socialization, nutrition and cooking skills, and seeing a project through from planning, planting, harvesting, and cleanup. They learn that no task is too small and each contributes to the success of the garden. One client received certification in composting at the New York Botanical Garden and has set up composting at a few of the residences.”

“I would have to say almost every single job involved in gardening has a lesson to teach, a life lesson. From seeding and watering in the greenhouse, you learn that attention to detail is so important. Life or death for those little seeds depends on your continual watch and care. When you watch the plants grow and grow and bloom—somewhere inside you are growing and blooming too. This begins a foundation of self-worth and respect.”

—Anonymous quote from a trainee at the Homeless Garden Project, Santa Cruz, CA

Since 1984 UWNYC has served as a local administrator for HPNAP. Through that program, UWNYC has supported 23 different urban farm projects since 2001, in all five boroughs of New York City, including eight community gardens, eight backlot/backyard urban farms, four rooftop farms, and—as proof that urban gardening truly can take place anywhere—three hydroponic farm systems, which grow plants without soil.

An HPNAP grant also funded the first year of the rooftop farm at Community Counseling and Mediation (CCM) Georgia’s Place, a residence in Brooklyn, New York, for the formerly homeless. Many there have little to no experience maintaining a schedule, making it difficult to assign gardening duties, such as weeding or watering, that must be done at certain times each day. To engage participants, Assistant Program Director David Watts got creative, asking case managers and group leaders to hold counseling sessions and group wellness meetings on the roof. As clients acclimated to the garden space, they began to connect with and take interest in and ownership of the rooftop farm. “When I think of horticultural therapy, I think of Georgia’s Place,” says Leigh Kusovitsky, nutrition resource manager at UWNYC. “It was hard to get them involved, but ultimately they had a lot of buy-in. One resident would go up—she was asthmatic and had pretty severe mental illness—and oversaw two different beds on the roof. It was therapeutic to take time for herself, and she thought the air was easier to breath—I think that was kind of beautiful.” Watts agrees and notes that the residents are now choosing more vegetarian meals over meat-based fare, because they know where the food comes from.

In the Bronx, Praxis Housing Initiatives—New York City’s largest provider of transitional housing to homeless people with HIV/AIDS—is planning an innovative supportive residence with an urban horticulture program. Features will include a second-floor greenhouse, teaching kitchen, orchard, and handicapped-accessible raised beds as well as an on-site farmers’ market. The project is Praxis’ first major urban horticulture project at a housing site. “The idea is that not only will residents be able to use the horticulture spaces but this also will help integrate residents into the community—a way to use gardening as community development,” says Jolie Milstein, director of real estate. “That is a hugely important part of our mission. Where we are resident with a housing program, we want to engage the community, and we see gardening as not only therapeutic for our residents but as a way to bring people together as a communal activity.”

Perhaps one of the most surprising benefits of involvement with therapeutic horticulture is its impact not just on the homeless and others experiencing poverty, but on their caregivers and advocates. The relationship between a service provider and a client improves significantly when the two work together in the garden, and this collaboration eases some of the inherent stigma facing homeless clients. Many residents of Georgia’s Place grew up on farms in the Caribbean or in the American South; Watts believes that work in the garden reconnects these clients to a time in their lives before the strife and drama of their recent years. And staff at the HGP find that gardening activities provide a tangible understanding of client needs that goes deeper than what an office session could yield. Says one staff member: “I have been able to gain a new understanding of homelessness and the varied problems and experiences that go with it. I had strong pre-conceived notions about the homeless community before coming here, and it was one of my goals to disband those and get a chance to hear a bit more about some of the trainees’ stories while working with them.” These strengthened relationships ultimately benefit the clients, who receive specialized care as a result. One staffer admits, “I have learned to love and care for people I never would have looked at twice.”

The Bridge has a horticultural program allowing residents to work in gardens, eat fresh vegetables, and receive nutrition and cooking education.

Horticultural therapy and therapeutic horticulture in supportive housing have—so to speak—room for growth, but a fair number of challenges exist. The biggest is that “it’s hard to fund,” says Mayrose of the therapeutic leg of her program. “The jobs-training program is easier to fund because it’s pretty cut and dried—X number of people get jobs, and we can show it’s working—whereas with horticultural therapy it’s much more about wellness and overall impact. If we had more documented research on programs that are out there and working—we know they are working but how are they working and why are they working? If we had that type of data, that would get more attention to programs and get more funding.”

Despite the challenges, Milstein and other providers are hopeful about the future of horticulture in meeting a variety of needs for impoverished Americans.

“In an environment of diminishing resources, payback for investment in urban horticulture and housing projects is big and visible, and I think we will see more health-care providers [and] insurance companies [provide] corporate support for urban agriculture because it has the same goals as the private companies,” says Milstein. “There are a lot of partnerships to be made around people taking responsibility for their food needs and engaging. There are all kinds of points of entry for urban horticulture—it doesn’t have to be taking over a huge roof—there are increasing numbers of teaching opportunities. Something as small as growing a tomato can lead you into something larger.”

A new project in the works, involving several parent organizations, could just be the solution to the challenges regarding data and even funding. The Healthy Housing through Horticulture Program is Praxis-conceived and is endorsed by The Network as well as the Corporation for Supportive Housing, The Hort, Enterprise Green Communities, and other organizations. “We have been actively pursuing building citywide and even regional, and hopefully national infrastructure around promoting horticulture in affordable housing projects,” says Milstein. “The idea is to link everybody up that is trying to or successfully using horticulture in housing projects both in NYC and beyond. When a group wants to include urban or non-urban horticulture in their housing project, there should be a database and a network of existing programs to contact and learn from,” she adds. “We believe that by coming together with our collective interest in horticulture we can help each other and really increase our chances of success.”

Several participants in the Homeless Garden Project answered our questions about horticultural therapy.

Here are some of their responses:

UNCENSORED: What techniques are taught through horticultural therapy? What skills are learned? What impact does horticultural therapy have on mental and emotional health?

HGP Trainees: “Nurturing living plants helps you nurture yourself, and in turn, those around you.” ν “I learn patience with myself and the people I work with.” ν “I learn focus and persistence with the task; the joy of work.” ν “I learn how to keep something alive.” ν “Flowers and veggies = happiness.” ν “Nothing enlightens the soul like putting one’s hands into fertile Earth; realizing that cupped in one’s hands, rolling in between one’s fingers is a tiny universe, constantly moving—before, during and after our time.” ν “In this fast-paced, negative society we live in, HT gives time to get grounded (literally) and feel one with the earth.” ν “HT promotes serenity and relief from everyday stress.” ν “Planting things makes you happy.” ν “HT promotes calm and joy.”

UNCENSORED: How does horticultural therapy impact, or have the potential to impact, the quality of living for children and families experiencing homelessness and poverty and/or living in supportive housing?

HGP: “It creates a safe, loving, joyful community feeling and belonging.” ν “It gives a sense of the magic of good food.” ν “Communities in need growing food for other families in need strengthen our community as a whole.” ν “It offers a healthy escape from limitation and a chance to get outside the temporary setbacks. Opens up possibilities for the future.” ν “It gives people something positive to do with their time and brings families together.” ν “Harvest and farm work bonds families together.”

UNCENSORED: Are there any other memorable experiences with horticultural therapy you would like to share with our readers?

HGP: “We have special needs pals that pick edible flowers for us often.” (Laurel Street, a day program for people with developmental disabilities, brings a group out to the farm nearly every weekday. They’ve been doing this for years and there is a wonderful chemistry and friendship between HGP trainees and Laurel Street’s participants.) ν “Observing the sense of joy with special needs visitors. The garden is often the highlight of their day. Miraculous.” ν “Seeing the smiles of the special needs volunteers.” ν “My first day on the farm, I was weeding and the ducks welcomed me all morning by helping me feel included.” ν “Feeling proud to share our hard-earned produce with foster youth, hospice patients and victims of domestic violence.”

“I would have to say almost every single job involved in gardening has a lesson to teach, a life lesson. From seeding and watering in the greenhouse, you learn that attention to detail is so important. Life or death for those little seeds depends on your continual watch and care. When you watch the plants grow and grow and bloom—somewhere inside you are growing and blooming too. This begins a foundation of self-worth and respect.”

—Anonymous quote from a trainee at the Homeless Garden Project, Santa Cruz, CA

Working with Nature Provides a Fresh Start for Homeless and Once-Homeless Families and Adults

Additional quotes from Venezia Michalsen, an assistant professor of justice studies at Montclair State University.

Venezia Michalsen, assistant professor of justice studies at Montclair State University, told UNCENSORED, “For women, programs that work must take into account the practicalities of women’s lives in reentry,” many of which are the same as for men: “somewhere safe to live, a way to get income, a way to be healthy mentally and physically, a way to be sober.”

Michalsen added, however, “Women have different needs from men in some domains, such as the fact that they generally have different mental health spectra, trauma histories, substance abuse histories, etc. In particular, women’s relationships with their children are often quite different than those of men, and the resulting needs are different. Women need child care, where men are worried about child support.”

With regard to mental health spectra, Michalsen explained, “Women in prison are diagnosed with mental health problems than men by about 20%, and they have different mental health problems than men. This is similar to the general US population, of course, where women are twice as likely as men to have a diagnosis of depression, for example. This goes along with women’s dramatically higher rates of trauma exposure, both as children as adults.

Resources

Supportive Housing Network of New York; New York, NY ■ Horticultural Society of New York; New York, NY ■ American Horticultural Therapy Association; King of Prussia, PA ■ My Big Backyard, LLC; Denton, MD ■ Homeless Garden Project; Santa Cruz, CA ■ Gateway Greening; St. Louis, MO ■ The Bridge; New York, NY ■ Georgia’s Place; Brooklyn, NY ■ United Way of New York City; New York, NY ■ Praxis Housing Initiatives; Bronx, NY.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Guest Voices—

A New York City State of Mind

by Matthew Leib

Matthew Leib is a graduate of Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism. When not cartooning, he works in advertising.

To download this cartoon, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The Historical Perspective—

Excluding the Poor: Public Housing in New York City

by Ethan G. Sribnick

In the 1930s, in the midst of the Great Depression, federal, state, and local officials developed their most radical response to the problem of inadequate shelter for the poor and working class: publicly built and subsidized housing. In the years after World War II, stark high-rise towers became a common feature in the landscape of America’s cities. There was never, however, a clear consensus over the purpose of public housing. Some believed public housing should provide shelter for the poorest and most unstable families. Others hoped to create thriving, financially stable working-class communities by restricting residency to working families who could demonstrate their potential as upstanding tenants. In New York, unlike in most American cities, the more restrictive view of public housing often won out; never have welfare recipients formed the majority of public-housing tenants in this city. Today, as activists and policy makers in New York clamor to make more public-housing units available to homeless families, it is helpful to understand this history of disagreement over public housing and how these competing views continue to inform debate over poverty and homelessness.

Public housing in New York emerged from decades of struggle to improve the housing and communities of the poor and working class. In 1934, when the reformist mayor Fiorello La Guardia took office, thousands of families still lived in substandard buildings. Housing reforms passed in 1901 required some basic standards of ventilation, safety, and hygiene, but more than 350,000 tenements built before these reforms were still standing. Thirteen hundred of these buildings still relied on outhouses in the yards, another 23,000 provided toilets only in the halls, and 30,000 had no bathing facilities. From 1918 to 1929 there were four times as many fires and eight times as many deaths in pre-1901 tenements as there were in structures built after the passage of the 1901 law.

First Houses, pictured here in 1939, replaced poorly constructed tenement housing on the Lower East Side with modernized apartments for low-income families. Almost 4,000 families competed for only 122 apartments when First Houses opened, in 1935. Photo courtesy of the New York City Housing Authority.

La Guardia’s first step was to push through a new housing code requiring landlords to retrofit their buildings to meet new standards for safety and sanitation or to board them up. Many buildings were so old as to make the required improvements impossible. “The only ultimate cure for them,” opined Tenement Commissioner Langdon Post, “is dynamite.”

In February 1934 the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), the city’s new public-housing agency, began its state-mandated mission to provide for “the clearance, replanning, and reconstruction” of the slum districts of New York. Over the next four years, NYCHA demolished 1,100 tenement buildings, removing 10,000 rental units. Property owners abandoned an additional 40,000 apartments. The result of all this slum clearance was a shortage of low-rent housing for the poor and working class.

NYCHA’s next step was to provide new housing with support from the state and federal governments through the development of a number of public-housing projects. NYCHA’s initial housing project, the appropriately named First Houses, opened on the Lower East Side of Manhattan on January 15, 1935. The original plan had been to renovate existing tenements, tearing down every third building to provide more light and air, but the tenement houses were in such bad condition that all but three on the block had to be demolished. Even with the additional construction costs, NYCHA was able to offer apartments for the reasonable rent of $6 a room per month. The complex included central heat—a rarity in tenements, which usually relied on coal stoves for warmth—and gardens and playgrounds integrated into the project grounds. NYCHA received 3,800 applications for the 122 units in the development. The high demand for public housing continued as NYCHA expanded into larger complexes. Harlem River Houses, in Upper Manhattan, received 14,000 applications for 574 units, and Williamsburg Houses, in Brooklyn, received 20,000 applications for 1,622 units. Based on this demand, public housing in New York appeared to be a resounding success.

Residential programming was one way that NYCHA attempted to build a sense of community within its projects. Here, children gather for “Story Telling Hour” at Williamsburg Houses in 1945. Photo courtesy of the New York City Housing Authority.

The high demand for inexpensive housing allowed NYCHA to be selective in choosing residents. The families that moved into Williamsburg and Harlem River Houses in 1937 first passed through a lengthy screening process. The first cut of selectivity was by race—the projects were strictly segregated, with Williamsburg open only to whites and Harlem River only to blacks. Next, NYCHA evaluated applicants by both “need and merit.” However, NYCHA had no interest in providing housing for the poorest New Yorkers; only those families headed by breadwinners with stable jobs were eligible for these projects. In addition, potential residents also had to prove to NYCHA administrators that they had insurance policies, bank accounts, and proper housekeeping skills.

The population that first entered public housing in New York were, as a result of these policies, rarely those most in need of it. Every family selected for Harlem River Houses, for instance, had at least one wage earner, and one-fourth of the families had two people working. Considering that unemployment in Harlem was at least 40 percent, families entering the project were well-off compared with the population of the surrounding neighborhood.

Part of the reason for this selectivity was the belief of NYCHA’s leaders that they were building not just housing, but fully functioning communities. On-site day-care centers, nursery schools, and after-school programs offered care for residents’ children. Outdoor spaces included tennis and handball courts. Meeting rooms facilitated the development of clubs and organizations such as tenant associations, community newspapers, and Boy Scout troops.

At times the involvement of NYCHA staff in tenants’ lives bordered on paternalistic. Miriam Burns, who grew up in the Harlem River Houses, distinctly remembers “a white woman, I guess she was the manager,” coming to her family’s apartment to collect the rent. “She was not averse,” Burns recalled, “to looking in the refrigerator.” The NYCHA agents were instructed to chat with the families to determine if they needed help and to make sure they were properly caring for the apartments. Burns reflected that today such invasions into people’s homes would seem “unbelievable,” but as she remembers it, her mother seemed happy to show off her housekeeping skills. NYCHA would eventually phase out rent-collection visits, but the sense of staff involvement in tenants’ lives would continue.

NYCHA bought and destroyed existing housing to make room for its developments. This image from 1936 shows twelve blocks cleared prior to the construction of Williamsburg Houses. 78 percent of the demolished apartments had no central heating and 67 percent had no private toilets. Photo courtesy of the New York City Housing Authority.

Over this early period, NYCHA was under increasing federal pressure to provide more housing for the very poor. The United States Housing Authority (USHA), a precursor to the Department of Housing and Urban Development, believed that public housing should provide low-cost apartments for the lowest-income population. NYCHA administrators resisted that view, fearing that extremely poor families, especially those receiving public assistance, would not be able to care for their housing properly. They also believed that the characteristics and behavior of poor families would undermine the communities NYCHA hoped to create within the projects. In 1953 NYCHA established an additional 21 categories of non-desirability in evaluating applicants. These included narcotic addiction, single parenthood, out-of-wedlock children, teen parenthood, “highly irregular work history,” “lack of parental control,” mental illness, poor housekeeping, and “lack of furniture.” While having only one of these characteristics would not automatically exclude an applicant from admission into NYCHA housing, it would lead to extra scrutiny and make placement more difficult. These factors kept many families in need of shelter out of public housing. While the number of families on public assistance in NYCHA rose over the 1940s and 1950s, the authority placed families so that no individual project had more than 20 to 30 percent of its families on welfare.

NYCHA also remained extremely vigilant with regard to the racial composition of its projects. While the policy of racial segregation established in its first projects was quickly abandoned, NYCHA paid close attention to race in evaluating and placing applicants. The agency operated under the belief that whites would abandon public housing if it became predominantly black. The “overwhelming population in New York City is white,” explained settlement-house leader Mary Simkhovitch, a member of NYCHA’s board. “We don’t want to act in such a way and do this thing in such a way that it will deter white people from going into projects.” In following this directive, NYCHA created some projects that were majority-white and others in which a majority of families were black or Puerto Rican. In order to maintain a “racial balance” across the NYCHA projects, administrators discriminated against blacks and Puerto Ricans, the groups that had the most difficulty in finding decent affordable housing in the private market. Yet, even with these restrictions, by 1959 NYCHA housing had become mainly black and Puerto Rican, with most whites concentrated in projects in the outer boroughs.

In the mid-1960s, the debate over the purpose of public housing resurfaced. Officials within city government began pressuring the housing authority to accept more poor families in desperate need of housing. “Problem families must have new housing before they can be helped,” declared Welfare Commissioner James Dumpson in 1965. He estimated that 300,000 of the people “forced to live in this city’s slums and rat-infested tenements” had been found ineligible for NYCHA housing. NYCHA chairman William Reid responded that the problems these families faced were not ones that public housing was equipped to confront. “It’s a welfare and social problem,” he explained. These families “have to learn to live in public housing before they move into the projects.”

In 1968 NYCHA, acquiescing to some of its critics’ demands, announced that it would no longer “deal with the morals of applicants. Thus, for example, no family may be declared ineligible solely because the applicant had an out-of-wedlock child.” In that same year, the number of families in NYCHA housing who received welfare reached a new high of 15.4 percent. NYCHA also lost much of its autonomy in evicting residents, as a Supreme Court decision required new procedural protections for tenants. In 1973 the total welfare population of NYCHA reached 34 percent. While this was higher than NYCHA officials desired, it was still low compared with other cities. In that same year in Chicago, for instance, 49 percent of public-housing residents received welfare.

Also in 1973 President Richard Nixon announced a moratorium on the construction of new public housing. The radical experiment in publicly built and managed housing that began in the 1930s was over. In its place would come the Section 8 program, which provided federal vouchers in order to subsidize rent for housing procured in the private market. NYCHA projects would continue to provide housing, and the authority would come to oversee the Section 8 program, but there would be no further expansion of public housing in New York. Even as support for public housing diminished and pressure to take in more poor families increased, NYCHA persevered in its efforts to maintain mixed-income housing by assigning applicants to different tiers based on income and mixing tiers within projects.

This effort would be challenged, beginning in the 1980s, by the rise in family homelessness, which placed a new burden on NYCHA to provide housing for the extremely poor. By the mid-1980s Mayor Ed Koch had realized that the sharp rise in homeless families was not an anomaly but, rather, the start of a new trend. The temporary solutions the city had developed, such as placing families in hotels (soon dubbed “welfare hotels”) or in barracks-like congregate shelters, were not going to provide adequate shelter for the thousands of families in need of it. Koch turned to public housing to provide shelter for some of these families. Although NYCHA administrators protested that “the homeless need a whole range of social and medical services that the public housing program is simply not prepared to provide,” the Koch administration insisted that they offer around 2,000 apartments, about a third of their vacancies, to homeless families every year. This priority for homeless families would continue in various forms in the administrations of mayors David Dinkins, Rudolph Giuliani, and, at first, Michael Bloomberg.

Brownsville, Brooklyn, is dominated by public-housing developments. This image shows Brownsville Houses—27 six- and seven-story buildings built in 1948—in the foreground, as well as numerous housing projects that went up around it afterward, including Van Dyke I (1955) and II (1964), Howard (1955), Tilden (1961), Low (1967), Hughes and Glenmore Plaza (both 1968), and Woodson (1970). Photo courtesy of the New York City Housing Authority.

In 2005, as part of his new homelessness policy, Bloomberg discontinued the practice of giving homeless families a priority for public housing. The Bloomberg administration feared that this policy was encouraging poor families to “become homeless” and enter shelter in order to get to the front of the NYCHA waiting list. As Linda Gibbs, then the head of the Department of Homeless Services, explained, “We wanted to free up the Section 8 and Housing Authority units in order to reward and encourage people to solve their housing problems without moving through the shelter system.” Public housing, the administration believed, should reward those families who were working to improve their economic well-being—not the homeless.

Since the 1990s, NYCHA has largely reasserted its long-term efforts to limit the number of extremely poor families in public housing. As federal financial support for public housing has continued to decrease, NYCHA has attempted to recoup its losses by bringing in higher-earning tenants who can pay higher rents. In 1996, for instance, NYCHA gave top priority to working families with household incomes between $24,000 and $49,000 a year. The effort to attract working families, combined with the effects of the 1996 welfare reform—which pushed heads of families from welfare to work—has led to a significant decrease in the number of families in NYCHA housing receiving welfare. As of January 1, 2012, 47.2 percent of NYCHA families were working families and only 11.4 percent received public assistance. As of February 1, 2012, 163,995 families were on the waiting list for conventional public housing. NYCHA has largely returned to the policy of housing for the working poor envisioned by those who planned the first projects in the 1930s.

Today, New York’s politicians and advocates for the homeless are calling on the city to once again give homeless families priority for public housing. They hope that such housing will help stem the massive increase in the number of homeless families that the city has seen in the last few years. This debate will bring to the fore the question of what purpose public housing should serve. Should it truly be housing for the poorest New Yorkers, or should it remain more exclusive, primarily housing for the working class? As the city looks to various institutions to confront the growth in family poverty and homelessness, it remains to be seen if public housing will be part of the solution.

Resources

Bloom, Nicholas Dagen. Public Housing That Worked: New York in the Twentieth Century. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009. ■ Coalition for the Homeless. “State of the Homeless 2012,” May 31, 2012. ■ Kessner, Thomas. Fiorello H. La Guardia and the Making of Modern New York. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1989. ■ Murphy, Jarrett. “Chapter 3: Suddenly, No One Wanted to Pay for Public Housing.” City Limits, January 10, 2009. ■ New York City Housing Authority. “Fact Sheet,” April 26, 2012. ■ Quinn, Christine C. “Record Homelessness Calls for New Approach.” Huffington Post, June 13, 2012. ■ Radford, Gail. Modern Housing for America: Policy Struggles in the New Deal Era. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Experts Respond to Questions about the Biggest Misperceptions among the General Public about Homelessness