Publisher’s Note

Dear Reader,

ICPH is dedicated to alleviating family poverty and homelessness through a multi-pronged approach, involving employment, education, and housing. We are excited about this issue of UNCENSORED, which includes articles with compelling ideas on all three fronts.

In the area of employment: the Chicago-based National Transitional Jobs Network (NTJN) operates on the principle that adequately paid work is the key to becoming self-sufficient and remaining stably housed. The authors of our feature “Getting Families on Their Feet,” both representatives of NTJN, offer family service providers proven methods for combating homelessness through jobs.

With regard to education: the Minneapolis family shelter People Serving People works to rescue children from lives of poverty by helping them out at the start—building the executive functioning skills they need to succeed in school and life. Our Guest Voices essay details this organization’s very important work. Finally, San Francisco’s Compass Family Services, the subject of another of our features, has succeeded brilliantly on the housing front by helping struggling mothers, fathers, and children make the transition from homelessness to independence.

One secret to Compass’s success is its wonderful work in a less tangible but no less vital area, through services that acknowledge the trauma its residents have experienced. Those intangibles are also the focus on another organization, the Brooklyn-based Children of Promise, NYC—the subject of our feature “The Invisible Victims”—an after-school program that provides counseling and other support to the young sons and daughters of incarcerated parents.

As UNCENSORED continues to shine a light on the terrific work being done around the nation, we welcome your questions, comments, and ideas.

Sincerely,

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, Publisher

President and CEO, Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Getting Families on Their Feet:

Steps for Integrating Employment Programming into Homeless Services

by Caitlin C. Schnur and Chris Warland

The authors are, respectively, the Workforce Research & Policy Fellow and the Program Quality & Technical Assistance Manager at the National Transitional Jobs Network.

With this article, UNCENSORED introduces a new kind of feature in the magazine, one that will offer specific advice to those serving homeless and struggling families. The practices described below may already be part of some providers’ programs, but we feel that this article by representatives of the Chicago-based National Transitional Jobs Network (NTJN) is a comprehensive guide to integrating employment into homeless services.

The NTJN is a Chicago-based national coalition dedicated to helping people with barriers to employment, including people experiencing homelessness, succeed in the workforce. The NTJN’s Working to End Homelessness (WEH) Initiative aims to highlight the role employment can play in preventing and alleviating housing instability. As a part of the WEH Initiative, the NTJN convened a national Community of Practice of workforce-development professionals from more than 20 programs serving individuals with barriers to employment, including St. Patrick Center in St. Louis, Missouri, and Blue Mountain Action Council (BMAC) in Walla Walla, Washington. These programs worked alongside the NTJN for almost a year to share their best employment practices, identify challenges to their work, and create effective employment solutions for people experiencing homelessness.

***

Gene, an honorably discharged army veteran with a young daughter, had a job with a tree-service company and owned a home. But when Gene’s income dropped after his work hours were cut back, his home fell into disrepair and he and his daughter found themselves without a place of their own to live. Like so many families experiencing homelessness, Gene and his daughter “doubled up” with family and friends to avoid having to sleep on the streets or enter the shelter system.

That was when Gene heard about St. Patrick Center, a nonprofit organization in St. Louis that provides housing, employment opportunities, and health services for people who are experiencing or at risk of homelessness. Gene turned to St. Patrick Center for support.

Recognizing his need for employment with family-sustaining wages, Gene’s new case managers placed him in St. Patrick Center’s Veterans GO! Green program, which provides veterans with paid job-training opportunities in sustainable horticulture, landscape management, and recycling and waste management.

A man participates in St. Patrick Center’s Building Employment Skills for Tomorrow (BEST) on-the-job-training program for people experiencing homelessness.

While in training, Gene received an offer for a full-time job with a family-owned business that buys, processes, and sells scrap iron and steel. Still employed with them over three years later, Gene strives to arrive early, never miss a day, and advance in his position—and his commitment to workplace success has been recognized and rewarded by his employer.

With full-time work and a stable income, Gene and his daughter have moved into their own apartment. Gene is saving money to purchase a pickup truck and his own lawn-service equipment, and he is thrilled to be able to provide for his daughter’s extracurricular gymnastics training—as well as maintain safe, stable housing.

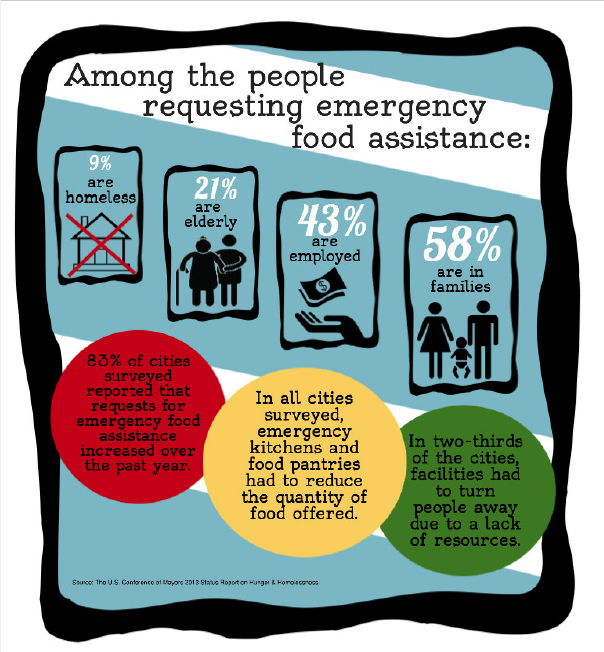

Gene’s story is an example of why employment and earned income are critical for ending the pervasive problem of family homelessness in the U.S. On a single night in January 2013, 222,197 people in families—including 130,515 children—were experiencing homelessness. This point-in-time count likely underestimates the number of families that lack places to live, because it does not account for families, like Gene’s, that are in doubled-up situations or otherwise at imminent risk of being without homes.

While families experiencing homelessness are by no means homogeneous, they are most often made up of single mothers in their twenties with young children. Insufficient earned income leaves many of these families unable to maintain housing. Most people experiencing homelessness say they want to work and believe that earned income would help them become and remain housed. When asked, they frequently rank paid work as their primary need. Nancy Yohe, senior director of employment and veteran services at St. Patrick Center, has seen this in her own practice: “Many people [experiencing homelessness] will come to us saying that they just want a job, and that they’ll do anything.” City leaders also agree that poverty and unemployment are among the leading causes of family homelessness in their communities. Connecting homeless adults to stable, earned income through employment is a critical tool in the ongoing fight to alleviate and end family homelessness.

“There is a tremendous opportunity for those who serve people experiencing homelessness to prioritize employment as a pathway to stable housing and offer clients comprehensive employment programming.”

As critical as employment is, heads of households experiencing or at risk of homelessness are likely to face barriers to employment such as low educational attainment, limited work-related skills, and irregular work histories. Other factors—such as poor physical or mental health, domestic violence, or simply having exhausted the support of friends and family—also increase the risk of family homelessness and may act as further barriers to getting and keeping jobs.

Fortunately, research has shown that when offered individualized employment, housing, and supportive-service options, people experiencing homelessness can surmount barriers to employment and find and keep jobs. Heads of households experiencing homelessness also have diverse strengths, such as past work experience and a desire to care for their children, that can be leveraged to help them succeed in the world of work. There is a tremendous opportunity for those who serve people experiencing homelessness to prioritize employment as a pathway to stable housing and offer clients comprehensive employment programming.

Integrating Employment into Homeless Services

“Having a job is vital to becoming self-sufficient,” says Michelle Goodwin, workforce development specialist at Blue Mountain Action Council (BMAC), a nonprofit organization serving low-income people in Walla Walla since 1964. “At BMAC, we’ve offered employment programming since our opening day.” Like BMAC and St. Patrick Center, any group serving people experiencing homelessness, whether a shelter, supportive housing program, or health care provider, can take steps to help its clients find and keep good jobs—and many of these steps can be taken immediately and at little or no additional cost.

The first option to consider is partnership, a practice embraced by both BMAC and St. Patrick Center. As Goodwin points out, “By partnering with outside organizations, BMAC can provide wraparound services that use the skills and services of different agencies to help participants.” Chances are that other organizations in a provider’s area offer services to people with barriers to employment. In some cases this will be the local public workforce center, perhaps called a One-Stop Career Center or American Job Center. One of St. Patrick Center’s food-service training programs is housed in its local public workforce center, and BMAC’s Goodwin is at her local center twice a week. “I’m involved in the job club we have over there, and we partner in teaching classes,” Goodwin explains. “I also refer participants to workshops where they can learn about writing résumés and cover letters and build job-interviewing skills.” In the majority of cases, the most effective partner may be a community- or faith-based organization. Often, these partnerships can be mutually beneficial, especially those between housing and employment programs: an employment service provider may take job-seeker referrals from an organization that provides housing and refer individuals in need of housing assistance. While memoranda of understanding (MOUs), or formal agreements between organizations, are sometimes useful, often such partnerships are informal.

Program staff can also begin introducing employment as a goal for clients during routine interactions, counseling sessions, and discussions of individualized plans. Motivational interviewing, an evidence-based counseling method that strengthens an individual’s determination to change his or her behavior, can help clients who are ambivalent about pursuing employment recognize that a job is important for achieving personal goals—and help the individual commit to a job search. Goodwin is an enthusiastic proponent of motivational interviewing, which allows clients to recognize their own strengths and work with their case managers to create plans rather than simply being told what to do. Yohe, also an advocate of motivational interviewing, is excited that St. Patrick Center is exploring ways to integrate the practice into its employment programming. “Motivational interviewing is the key to engagement,” Yohe says. “Using open-ended questions, reflecting, and normalizing clients’ experiences—all of those techniques help us improve our services to clients.” Finally, it is best to begin offering employment assistance, including a range of options for how to pursue employment, when the individual expresses a desire to work.

A St. Patrick Center BEST participant takes a break from his job.

For relatively little cost, programs can offer basic job-search assistance, such as hosting on-site classes in résumé writing or interview skills. Debbie Huwe, who works in BMAC’s transitional-housing program, says that she and her colleagues try to provide basic job-search preparation to all of BMAC’s housing clients, including those who haven’t been referred to one of BMAC’s more intensive employment programs. “We’re not job specialists, but once a month we have a life-skills class and some of what we teach is work-related skills. We’ll work on résumé building and mock interviewing,” she says. If it is not feasible to offer job-search assistance classes on-site, staff members or volunteers may be able to help job seekers search online postings or fill out electronic applications. “One of our volunteers will call employers and see if they have openings, and then put together a sheet of local opportunities, and another volunteer helps with one-on-one mock interviews and applications,” says Yohe.

By providing the basic tools for conducting a job search on-site, providers can lower the barriers to beginning to look for a job. For example, Internet-connected computers and telephones can facilitate self-directed job-search activities. “We have 16 computers where clients can conduct an online job search and check e-mail,” says Yohe. Also, setting up dedicated phone lines or connecting clients to Community Voice Mail—a service that gives participants private, ten-digit phone numbers that go to personalized voice mail boxes where they can receive messages—provide ways for prospective employers to respond to applications without revealing that applicants are staying in shelters or supportive housing.

If an organization is willing and able to provide more intensive employment programming in-house, one practical next step would be to dedicate staff in employment-services roles, as both St. Patrick Center and BMAC do. “My position is job coordinator,” Goodwin explains. “I work with agencies in town to help people get employment but also gain work experience and training. Sometimes I act as a job coach, helping with résumés and interviewing skills. I may also check in with supervisors to see how people who have found jobs are progressing and the new skills they’re learning.”

Organizations may consider committing staff to roles in job development, job coaching, and work-readiness training. Job development involves reaching out to employers, identifying work opportunities, and matching those opportunities to clients’ interests and skills. Job coaching means developing individualized employment plans and guiding participants through the process of becoming and remaining employed. Work-readiness courses develop an understanding of basic job-related concepts such as punctuality, personal presentation, and effective workplace communication. In small employment initiatives a single staff member sometimes fills these roles; in larger programs they are typically specialized roles.

When organizations have secured sufficient resources to support more intensive employment programming, they can look to proven models such as transitional jobs or supported employment, also known as individual placement and support (IPS). These intensive interventions, which are more effective for helping job seekers with multiple or serious barriers to employment find and keep jobs, require more long-term planning, staffing, and resource development for successful implementation.

Peer learning relationships with other providers can play an important role in developing new employment-services programming. Connecting with a similar organization that has successfully implemented employment programming for people experiencing homelessness can help a new program avoid pitfalls and identify effective practices. If an organization is interested in forming a peer learning relationship with an established program, the NTJN may be able to connect that group with a peer.

Jennifer and Rob, a young couple with a toddler, struggled to make ends meet. Without high school diplomas or work experience, they had great difficulty in finding employment to secure housing. Since their sole income was the $385 per month they received through Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), it’s no surprise that the young family became homeless. Jennifer, Rob, and their toddler doubled up with Jennifer’s family, but having eight people in the house was not sustainable. That’s when Rob was arrested—and when the family was connected with BMAC.

BMAC offers a range of services to families experiencing or at risk of homelessness, including access to transitional housing and robust employment programming to set families on the path to self-sufficiency. BMAC quickly placed the family in housing and then helped mitigate the barriers to employment that had left the parents unable to afford a home.

BMAC connected Jennifer and Rob to the local community college, where they earned their GEDs. Rob’s court fees were settled, and BMAC placed him in its wage-paid, on-the-job training (OJT) program, which matches low-skilled workers with employers who are partially reimbursed for providing job-specific training to prepare an individual for work with that or a similar employer.

With Rob on the path to employment, BMAC provided the financial support Jennifer needed to train as a certified nursing assistant (CNA). Jennifer successfully completed CNA training but still had a significant barrier to employment—her limited work history. BMAC again leveraged its OJT program, helping Jennifer secure a job with an employer who was willing to provide her with hands-on CNA experience in exchange for partial reimbursement of these job-training costs. Jennifer still works for this employer, who hired her for an unsubsidized job in June 2013.

Today, the family has its own home. Though Rob lost his job when the business that had employed him closed, he hopes to enter culinary school to gain further skills and find a job that will fulfill his passion for cooking. With Jennifer’s income, the family is able to maintain housing and continues to take steps toward financial stability.

Recommendations for Delivering Employment Services for Families Experiencing Homelessness

Families experiencing homelessness will bring certain strengths, barriers, and needs to the process of finding, succeeding in, and advancing in employment. Homeless-service providers should recognize that heads of households usually require tailored strategies for leveraging those strengths.

Dependable, affordable child care is absolutely essential for parents of young children to be successfully employed. Parents experiencing homelessness may have weak social networks or may have exhausted those networks. This can make it more difficult to secure backup child care with family or friends, which places even greater importance on connecting these families with available child care subsidies and affordable center-based child care. Providing on-site child care for parents still engaged in employment programming may also make it easier for these parents to take full advantage of available services. “St. Patrick Center has a drop-in center for children whose parents are here for programming,” says Jess Cox, St. Patrick Center’s employment services manager. “Kids can be in a safe, fun environment while their parents are going to classes or meeting with case managers.”

Some employment programs serving families experiencing homelessness also teach household management skills to help parents balance work and home life, prepare quick, healthy meals, and maintain household budgets. “We have a living skills program that includes budgeting, landlord-tenant rights, preparing meals, and nutrition education,” Yohe explains. “There’s also a GED component for individuals who have not completed high school.”

To ensure that families become and remain stably housed, employment programs should take on the challenging task of helping parents find jobs with family-sustaining pay and benefits. Unfortunately, not all employment opportunities will allow individuals or families to escape homelessness and poverty. As Yohe puts it, “A job ‘doing anything’ is not necessarily the right answer.” In fact, many people experiencing homelessness already work, and recent Census data shows that over 30 percent of poor children are in families with at least one member working full-time—as are over 50 percent of children in low-income households, or those earning less than twice the federal poverty level income ($19,790 for a family of three in 2014). In the current U.S. labor market, many of the positions available to people experiencing homelessness are low-wage and/or part-time and fail to pay family-sustaining wages, offer access to health insurance, or present opportunities for advancement. “A lot of St. Patrick Center’s clients are used to working for a temp service or in an under-the-table job,” says Cox. “We definitely encourage them to look for employment at a higher level, something that does have benefits and good pay. We want to help them to see that they should be investing in themselves, because the temp and under-the-table-jobs haven’t been working.”

It is important to help parents find jobs with family-sustaining pay and benefits. Not all employment opportunities will allow individuals or families to escape homelessness and poverty. As Nancy Yohe of St. Patrick Center puts it, “A job ‘doing anything’ is not necessarily the right answer.”

Programs have different strategies to help individuals find and advance in quality, family-sustaining jobs. “We make sure that the job leads we’re giving our clients are with good employers, not employers who will take advantage of them,” says Cox. This means targeting industries known for promotions, raises, and benefits and building relationships with high-quality employers. Focusing on high-growth sectors is also important. “Typically, we try to place people into positions that are in demand in our local area,” says Goodwin of BMAC. “A lot of these jobs are in the medical field.” Increasing clients’ skills is especially important, as industry- or job-specific training that leads to industry-recognized certificates has been shown to help low-income workers increase earnings and access benefits. “We work with Walla Walla’s community college, which offers our clients education and skill enhancement,” Goodwin explains. “We can assist our clients in getting a certified nursing assistant license or with courses that will prepare them to be an administrative assistant or medical receptionist.” Referring to the OJT programming BMAC provided to Rob and Jennifer, Goodwin adds, “We also have some job training programs for people who are under-skilled—we can reimburse companies up to half of participants’ wages to enhance their skills.”

It is also critical to offer employment services using a strengths-based approach. “Heads of households tend to have a stronger work history [than single adults experiencing homelessness] and tend to be motivated about finding employment because it’s not just themselves they have to be concerned about, it’s their children,” Yohe says. Indeed, because many families experience homelessness for primarily economic reasons, parents or heads of households are likely to have recent employment experience, transferrable occupational skills, and professional networks that programs can leverage to help them get work. Two-parent families also have a potential advantage in that one parent may be able to pursue further occupational-skills training while the other works, or one may provide child care while the other is at his or her job. Parents may also be able to arrange their work schedules so that while one parent is at work the other is at home, and vice versa. As Cox says, “If you’re a family unit, you’ve got someone backing you up.”

Families with children are more likely to be eligible for public benefits such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly Food Stamps) or TANF, which can help stabilize families financially while parents pursue training and employment. Low-income workers with dependent children are also eligible for the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), one of the largest and most effective national antipoverty initiatives. Some states also offer an EITC to workers.

Finally, while employment is a critical initial component of helping families transition out of homelessness, asset building establishes a “personal safety net” so that a family remains stably housed even in the face of future unanticipated expenses or job loss. Providers can incorporate asset-building strategies into their employment programming. “We absolutely do asset building at BMAC,” says Goodwin. “We offer MoneySmart classes, and our participants can come in to make one-on-one appointments to learn financial management skills.” Financial education can help connect heads of households to safe and affordable financial products such as low- or no-cost checking accounts; educate them about predatory lending and credit card costs; and teach practical skills, such as budgeting and balancing a checkbook. Homeless-service providers can also help customers claim tax credits such as the EITC and the Child Tax Credit (CTC) by connecting heads of households to Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) sites, where qualified low-income individuals can receive free tax preparation and filing. For organizations with the resources to offer robust asset-building programming, developing a match-savings program encourages saving and increases assets to help families meet realistic financial goals—such as paying a first month’s rent or reducing debt—and lay the foundation for long-term stability.

Conclusion

In our nation’s efforts to end homelessness, we need to use all of the tools and strategies at our disposal. Earned income through employment is one important part of long-term solutions to ending homelessness, and any efforts to help families exit homelessness should include employment services. As Goodwin notes, “I see a lot of heads of households come in to BMAC saying that they really want a job, they want to increase their income and be able to take care of their families and get off of state assistance. They’re motivated, they know they can do it, they just need a chance.”

Resources

Heartland Alliance, Chicago, IL ■ City College of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA ■ Compass Family Services, San Francisco, CA ■ Public Policy Institute of California, San Francisco, CA ■ Stanford University Center on Poverty and Inequality, Stanford, CA ν Child Trauma Research Program at the University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA ■ Tipping Point Community, San Francisco, CA ■ Raphael House, San Francisco, CA ■ Star Community Home, San Francisco, CA ■ Office of Early Care and Education, San Francisco, CA.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Keeping Trauma at Bay:

Parent and Child Well-Being Is Key at Compass Family Services

by Carol Ward

On a sunny Monday in February in San Francisco, a group of female employees at Compass Family Services’ Clara House transitional-housing facility are abuzz with talk of a weekend newspaper article featuring one of their former clients.

The woman profiled, a forty-something former drug addict and convicted felon, has gotten clean, regained custody of her adolescent son, attended City College of San Francisco, and is waiting to hear about admission to a state university.

It’s the kind of story that truly resonates in a city where the problems of family poverty and homelessness weigh heavily.

A 12-year-old boy participates in Compass Family Shelter’s Youth Enrichment Project, one of several programs for children at the facility.

“It’s so great to have a success story,” says Erica Kisch, executive director of Compass Family Services, San Francisco’s hub for families in crisis. “The odds are so stacked against our clients that it’s often difficult for them to see their way out.”

According to a point-in-time survey conducted in January 2013, the city of San Francisco—whose population is roughly 826,000—had 6,436 homeless individuals, of whom more than half were unsheltered. The count showed 679 homeless persons in families and 1,902 unaccompanied children and youth under age 25. In short, getting by is difficult for many in San Francisco, the nation’s most expensive metropolitan area when it comes to housing; the high cost of living and a tight housing market combine to make even the most modest apartment out of reach for a large swathe of the population. A study released in October 2013 by the Public Policy Institute of California and the Stanford University Center on Poverty and Inequality found that when cost of living is taken into account, more than 23 percent of San Francisco residents live in poverty. The official U.S. government estimate is a bit more than half that figure, at 12.8 percent.

“The housing market is so out of reach for so many families, even if they’re not the lowest of the low-income like our families are,” Kisch says. “If our staff can’t afford to live in San Francisco, how can we expect our clients to live in San Francisco?”

Compass’s Role

For 100 years Compass Family Services has been helping families living in poverty in San Francisco. The group was launched in 1914 as Travelers’ Aid by members of prominent San Francisco families—the Crockers, Hearsts, Lilienthals, and Folgers. Its original purpose was to help young women coming across the country for the 1915 World’s Fair; at that time, the young women traveling alone were considered very vulnerable and quite risqué, Kisch notes. Over the years, the organization has helped various populations in need, including refugees, immigrants, war brides, returning servicemen and women, the deinstitutionalized mentally ill, transient hippies, and, since the early 1990s, homeless families. Kisch says the mission hasn’t changed much. “It really has always been to help the neediest San Franciscans,” she says.

“Today our mission is to help homeless families and families at imminent risk for homelessness to achieve housing stability, family well-being, and self-sufficiency,” Kisch adds. The budget for Compass Family Services came in at $8.3 million for Fiscal Year 2013. Of that, 72 percent was public funding, and the remaining 28 percent came from private sources.

“Some of our case management is just people talking about themselves,” says Bertie Mandelbaum, lead case manager at Compass Family Shelter. “We’re not working on a housing application or something concrete. We’re trying to help normalize their situation so they can try to heal from trauma.”

Each year the group provides 12,700 nights of shelter and holds 6,000 case-management sessions for families. Its success is apparent, with 95 percent of families in Compass housing programs not returning to shelters. Daniel Lurie, CEO and founder of Tipping Point Community, a Bay Area organization that provides grants to nonprofit groups addressing poverty, says that Compass’s “comprehensive approach and wide range of services address the many factors that contribute to homelessness in our community.” He adds that Compass “has changed the lives of thousands of Bay Area residents in need.”

Compass provides services to more than 3,500 parents and children each year, using a mix of seven programs to address the variety of needs that land on their doorstep. “Almost 100 percent of our clients have some sort of trauma or post-traumatic stress disorder,” says Susan Reider, director of Compass Clinical Services, which is one of the seven programs offered but is also integrated into the other six.

“Homelessness is a trauma for children,” Reider says. “Not having a stable home, not knowing where you’re going to sleep, being cared for by a parent who is scared or worried and not able to be emotionally present and provide what would be normal childhood experiences, that can be traumatizing.”

The group’s focus on mental health services differentiates it from some other service providers, Kisch says. She notes that Compass, in all its programs, provides “trauma-informed care.”

Compass Family Services has collaborated for several years with mental health professionals at the Child Trauma Research Program (CTRP) at the University of California, San Francisco, to offer trauma-informed services to the city’s vulnerable families. Vilma Reyes, a clinical psychologist and associate director of the CTRP, says of the professionals at Compass, “They’re very open to thinking about how trauma impacts young children and their families,” and she notes that Compass’s in-house programs work parallel to and in conjunction with her program. Reyes says CTRP and other specialists advise teachers at Compass Children’s Center on how to respond to children’s difficult behavior in the classroom.

Kisch says about Compass’s clients, “We recognize that every interaction with us, from when a family walks in the door and talks to the receptionist, or when they ask the janitor at the shelter for cleaning supplies, to the most intense therapeutic session, has the potential to be either therapeutic or further traumatizing, and given this, we train all staff accordingly.”

A child at Compass Clara House, a transitional-housing program for homeless families, enjoys a book in the common room.

Bertie Mandelbaum, lead case manager at Compass Family Shelter, says that the trauma a family has been through is always a backdrop for how she proceeds—and is sometimes front and center.

“Some of our case management is just people talking about themselves,” she says. “We’re not working on a housing application or something concrete. We’re trying to help normalize their situation so they can try to heal from trauma.”

Mandelbaum sees an array of mental and physical issues. “We have one woman with cancer—every symptom you can imagine,” she says. “It’s very difficult to deal with her, and how she interacts with her children reflects the pain she is in.” The solution, Mandelbaum says, is to try to help the mother channel her pain and have positive influences on her children. At the same time she must try to plan for a future—including housing and employment—that is far from certain.

The Compass Family Shelter is one of the group’s other six programs devoted to addressing varying needs, depending on where the family is in its search for housing. At any given time, families can be involved in just one or, more likely, a handful of the programs offered, according to Juan Ochoa, director of programs.

“There are usually many needs that are competing,” explains Ochoa. “We have to prioritize the areas we are working on with a family at any given time. If you focus on too many things at the same time, achieving results becomes really difficult.”

The Front Door

On that same February morning, a young couple with an infant and a preschool-aged child wait in the hallway outside the Compass Connecting Point office. The couple say they slept in a temporary shelter last night, as they have many nights, while waiting for a more permanent shelter room to become available.

“It’s really hard with the kids,” the young woman in the couple admits. “We don’t really have anywhere to go. We’re waiting to get into a shelter room but it takes a long time.” Neither she nor the children’s father is employed. The couple arrived this morning to collect food and diapers, as well as to meet with a case manager.

All families begin their quest for services at Compass Connecting Point, the centralized assessment, counseling, and referral center for San Francisco families facing housing crises.

Liz Ancker, program director for Compass Connecting Point, says families are quickly assessed to determine the solution that best fits their needs. For some who have income, rental assistance—for example, move-in funds or one-time eviction prevention—is most appropriate. Other families qualify for ongoing rent subsidies and are channeled to Compass SF Home, which offers that assistance along with a case-management component.

“We recognize that every interaction with us, from when a family walks in the door and talks to the receptionist, or when they ask the janitor at the shelter for cleaning supplies, to the most intense therapeutic session, has the potential to be either therapeutic or further traumatizing, and given this, we train all staff accordingly.”

The majority of families, however, need something more. Compass Connecting Point manages the waiting list for three city-funded shelters (including Compass), where clients are sent on the basis of space availability, and also works in conjunction with two privately funded shelters in the city, Raphael House and Star Community Home. All families on the shelter waiting list meet the definition of homelessness provided by the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act of 1987, which includes the lack of “a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence.”

“Families on the waiting list can expect to wait six, seven, or sometimes more months for a shelter placement, which will be a private-room placement they can stay in for six months,” explains Ancker.

Six months or more can be an awfully long wait for families who have no place to go. According to Ancker, those who wait go to emergency shelters, couch-surf, or sleep on the streets, in parks, in cars, or in other places not meant for human habitation.

James and Julie have experience with some of those scenarios. The couple and their three-year-old daughter moved to San Francisco from Georgia to find a better life and, they admit, to pursue the relatively generous benefits available in the city.

“We were told the resources here were the best for people looking to get on their feet,” says Julie. The family initially stayed with Julie’s sister, but the sister’s housing contract didn’t allow long-term guests, so they had to move on. They went next to an emergency shelter, then connected with Compass.

“This program has helped us a lot with bus tokens, food, hygiene, shelter,” says Julie. “In Georgia there are no resources and you’ve gotta know somebody to get a job.”

While waiting on a long-term shelter spot, Julie says she managed to get a job, although she was required to pass her GED exam for the job to become permanent. For help, she turned to Compass’s educational services, which provide GED training. James sought Social Security insurance benefits due to his diabetes and mental health issues.

While They Wait

Kisch says families entering Compass Connecting Point are often completely overwhelmed when they learn about the wait for shelter.

“To have to tell families with small children and babies and pregnancies—families in a state of crisis—that it could take eight or nine months for them to get into shelter is a horrible message,” she says. “It’s a horrible message for our staff on the front lines to deliver. It’s very demoralizing for everyone.”

Families are prioritized within the list if extraordinary need exists, such as a recent or imminent birth in the family. Also, some families that appear to be a good fit for the privately funded shelters are funneled to those instead of to the city-funded shelters. Rafael House has a highly structured program that requires early curfew, house chores, and intense group participation, Ancker says. Star Community Home has a similar model and can house only single women with one or two young children.

Almost without exception, though, homeless families are in for a wait. They’re required to check in with Connecting Point at least once a week, but many need more support. To soften the blow and to keep families from falling out of touch during the wait time, Compass Connecting Point offers a scope of services to help, Ancker says.

“We have our drop-in center, so they can come in and pick up a bag of food, bus tokens, and diapers, and that can happen three mornings a week,” according to Ancker. Other services are rooted in Compass’s focus on trauma-informed care: “We also do a lot of counseling, a lot of resources and referrals, and a lot of crisis intervention.”

For the past two years, Compass Connecting Point has had funding for three housing specialists, who “allow families to get a start on their housing search from the moment they walk in our doors,” Ancker explains. “Before we had these positions the only time families could really get support around their housing search was after they got into a shelter placement.”

“When you look at the fact that most waiting lists for low-income housing are a minimum of two years long, six months that they could have been on the waiting list is pretty significant,” Ancker adds.

More Permanent Solutions

Ochoa opens a door leading to what appears to be a small abandoned lot adjacent to the Compass Family Shelter in the Tenderloin area of San Francisco. It’s not much to look at, but he’s hoping for a transformation by the end of this year.

“We just got a grant to build a garden,” he says. In a crowded family shelter with no outdoor space, that little plot of land may serve as an oasis of sorts.

“When you are in the city, having a space that is green is invaluable,” he says. “We want kids to feel like this is their backyard.”

Compass Family Shelter, which provides housing for up to 22 families at a time, shares a building with another tenant. Resident living quarters occupy two floors, with a common area and kitchen on the ground floor. Rooms are generally small but vary in size. Upon entering the shelter, each family member is issued linens and dishes, which they can take when they leave, six months later. Families prepare their own meals most days, obtaining items from a food bank on the premises, Ochoa says.

Shelter residents are required to take advantage of the services outlined by their case managers. The program’s benefits are cumulative as clients work through the various phases of services.

“When you are in the city, having a space that is green is invaluable,” he says. “We want kids to feel like this is their backyard.”

“Participation in our programs goes from lesser to higher,” explains Ochoa. “Initially there is some case management and some requirements. Then when they get into shelter the intensity of services and intensity of mandatory case management and mandatory community meetings increases. These are things they have to participate in.” Activities include therapy, parenting education classes, intensive work toward housing and employment, and others.

“If the family goes into transitional housing it’s going to be the same [requirements] in addition to employment services,” Ochoa adds.

After a six-month stay at the shelter, which can be extended another six months if circumstances warrant, clients may get their own apartments, often with rental subsidies. Others qualify for permanent supportive housing with on-site case management, while some enter the transitional program, which offers two years of residence with services including child care.

The transitional program is offered at Compass Clara House. There, families live in small apartments that look onto an open courtyard. It’s a short walk from the shelter, but the pace of life on the street outside Clara House is less frenetic, more family-friendly.

Annette (not her real name), a resident at Clara House, is spending her two years at the facility trying to figure out how to move forward. The 33-year-old Annette, who struggles with alcohol dependency, transitioned from a residential recovery program into Clara House. For the first six months of her stay, she was required to take part in an outpatient program.

“That means no school, no work, just outpatient meetings and things like that,” she says. “At first I was like, are you kidding me? I just finished a year. But now I’m grateful that I got to relearn some things and also gain new tools, new coping skills, that help me deal with my day-to-day triggers.”

Annette lives at Clara House with her three-year-old daughter, who is enrolled in child care at the center. She is working to regain custody of two older children (ages 15 and eight), who were taken from her by Child Protective Services and currently reside with their grandfather.

Annette says she has “pretty much spent half my life battling my alcoholism” and hasn’t yet figured out how she will navigate a life of sobriety. “I’m not sure what I want to do, but since I moved here I’m working with case managers and the staff to figure it out. I feel more motivated.”

One daunting obstacle for Annette is figuring out her housing future. “We’re all supposed to be applying for housing but sometimes it gets to be too much,” she says. “But I’m going to focus on that. I want to get housing for myself and my children, something that is permanent and stable and safe. Not that I don’t have that here—it’s safe and wonderful but it’s not forever.”

For the Children

One point of intense pride within the organization is the Compass Children’s Center, which provides child care to homeless and extremely low-income families. Because there is capacity for just 70 children, the state- and city-funded slots are hard to come by.

Kisch says that if a family wins a spot, “they’ve basically won the lottery,” given the cost of full-time child care in San Francisco. Per-student expenses at Compass Children’s Center amount to $24,480 annually for preschoolers and $31,440 a year for infants and toddlers. The high price is largely due to a licensing requirement of one staff member for every three children, Kisch says, but the center “also has a rich layer of support services in place in order to address the psychosocial needs of the families we serve, so that pushes the cost up a bit.”

A toddler engages in an art project at the Compass Children’s Center, which provides enriched early childhood education and care to young residents.

For clients, winning slots means “being able to work or attend school, look for housing or do whatever is in their service plan to stabilize their family,” Kisch says.

Not all families who gain child care slots are Compass clients, but the agency manages the hefty waiting list for the city—numbering 3,305 children in April 2014, according to San Francisco’s Office of Early Care and Education.

Just a short walk from the Compass Family Shelter, the Children’s Center is in the heart of the Tenderloin. Grouped by age, the children work and play in an educational environment. The facility features a rooftop playground and a room where boys and girls can get exercise and strengthen motor skills. “A lot of our kids have deficits in that area,” Kisch notes.

Food is also a key component. “We provide breakfast, lunch, and snack, and a lot of the kids get their main nutrition from here,” Kisch says.

Looking Ahead

With demand for resources for impoverished families showing no signs of abating, Kisch and others are trying to decide the best way to proceed in the years ahead. One ongoing issue is how, or if, the city can define San Francisco residency, and whether that should be a prerequisite for accessing services. The cities and towns within the Bay Area form one large urban/suburban region, making it nearly impossible to determine residency for those who don’t have homes.

Kisch says that city officials are frustrated with the relative lack of resources in nearby communities. “I think there is a lot of expectation that San Francisco will bear an unfair portion of the burden,” she says. One goal for the near future is to build better partnerships with surrounding communities.

Those same communities might offer better options for Compass clients, Kisch adds. “While San Francisco needs to be a place for low-income families and not just the wealthiest, the reality right now is that families have the most options if they look as far afield as they are comfortable with, and we’ll help them do that,” she says.

Weighing residency requirements against residential reach, along with deciding how best to spend very limited funds, is sometimes daunting when the problem looms so large. Kisch says it’s often helpful to block out the big picture and focus instead on small achievements.

“Literally it’s one family at a time,” she says. “Any family that we can help stabilize is a victory.”

Resources

Children of Promise, Brooklyn, NY ■ Boys & Girls Clubs of America, Atlanta, GA ■ Community Word Project, New York, NY ■ College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA ■ The Pew Charitable Trusts, Washington, DC ■ Brooklyn Nets, Brooklyn, NY.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The Invisible Victims:

Children of Promise NYC Supports Young Sons and Daughters of Incarcerated Parents

by Alyson Silkowski

Every weekday after school, more than 200 children arrive at 54 MacDonough Street in Brooklyn, New York. After having a snack, the children, most between the ages of 6 and 13, disperse around the four-story building. The sound of sneakers against polished floor echoes as children run up and down the basketball court. Elsewhere in the building, children review homework and follow lesson plans in the computer lab. Others draw or compose poems. In one room, a group of children, holding enough instruments to form a string quintet, learn music note values. In a nearby room, a group of 10- and 11-year-olds sit, their desks arranged in a circle, and share their worries, anger, and frustration. They describe how it feels that their mom or dad is in prison.

This is Children of Promise, NYC, and it is no ordinary after-school program.

Serving the Underserved

Providing after-school programming and summer day camp to children of incarcerated parents, Children of Promise, NYC (CPNYC) was founded in 2007 with the goal of meeting the needs of the invisible victims of incarceration. “When a young person loses their parent, let’s say to military deployment, divorce, or death, there’s a level of sympathy and compassion that society displays,” Sharon Content, president and founder of CPNYC, explains. “But that level of empathy does not quite exist when your parent committed a crime.” And, as Content had discovered, few supportive services exist for these children.

After spending the earlier part of her career on Wall Street, Content moved into the direct-services field, managing Boys & Girls Club of America sites in the South Bronx. Families meeting with her about their children’s behavioral issues would sometimes tell her, often in hushed voices, that the child’s parent was in prison and that the boy or girl was having a difficult time. Content did not know where to refer those families for assistance. When she was ready to develop her own nonprofit organization, she remembered those families, whom she viewed as a “really underserved, neglected population,” and decided to create a program specifically for them. Jane Silfen, director of the Parenting Center at the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility for Women in Westchester County, New York, which refers children to CPNYC, says, “Children of Promise is a wonderful program that has helped support many of the children from our program who have a mother who is incarcerated. [CPNYC] provides a safe place for children to open up about what it is like to have a parent incarcerated without feeling any stigma. They also provide the children with a tremendous amount of educational and emotional support, which many do not get at home from their guardians.”

Taking a Therapeutic Approach

Today, leveraging a mix of government, foundation, and private funding, CPNYC offers after-school programming to more than 200 children and full-day summer camp to 125 boys and girls in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn. The organization has nine full-time and nearly 30 part-time employees. They also partner with local agencies and other nonprofits to provide some of the daily activities. (For example, an instructor from Unity Youth Chamber Orchestra has taught music to children at CPNYC, and the Community-Word Project has worked with them on journalism and photography.) All of the children CPNYC serves are directly impacted by incarceration, and the majority have a parent in prison. While the organization provides many traditional services, including recreation, arts, and tutoring, its therapeutic approach is what sets it apart.

“It’s Children of Promise NYC for a reason,” Sharon Content says, suggesting that CPNYC can be rebranded for any neighborhood where it is needed.

Co-locating with a mental health clinic, the Children of Promise, NYC Wellness Center integrates therapy into all of its activities. Children who are enrolled in the after-school program are assessed and linked to appropriate mental health services. Each child has a treatment plan tailored to his or her needs and approved by a psychiatrist on staff; the CPNYC staff use the plans as a guide to support children dealing with the challenges of having a parent in prison. In addition to the various activities that interest them—basketball, orchestra, spoken-word performances—children participate in group therapy as well as weekly or twice-weekly individual therapy sessions with clinicians trained in trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy. This clinical intervention, developed initially to treat children who had experienced abuse, is used to address the many symptoms of trauma.

When they arrive at CPNYC, the children often have untreated emotional difficulties and exhibit problematic behaviors. Many are aggressive and defiant, have avoided completing tasks in school, and have gotten in trouble for acting out. In addition to coping with the trauma of losing a parent, many of the children struggle with chaotic, stressful households. Some have been exposed to violence, and in more than one case, the child witnessed the parent’s arrest—or the crime itself. Many children harbor complicated, conflicting feelings. As one child said to Content, “It’s really difficult to love someone that everybody says is bad.” Content noted that at CPNYC, staff are trained to explain to children that dad (or mom) is not bad—but, rather, simply made bad choices—and that the child can feel good about loving the parent.

Impact of Incarceration

According to a 2010 report by The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2.7 million children in the U.S. have an incarcerated parent; mothers and fathers of more than 105,000 of those children are in a New York State prison or jail. Having a parent in prison has a profound impact on a child’s psychological development. Children of incarcerated parents are often withdrawn or combative, report extended absences from school and frequent suspensions or expulsions, and are more likely than their peers to commit crimes, perpetuating a cycle of intergenerational incarceration. One analysis of the studies on this subject found that children of incarcerated parents have twice the risk of poor mental health.

In developing CPNYC’s model, Content knew that the risks faced by children of incarcerated parents were unique. She decided, “If we really wanted to break the cycle of intergenerational incarceration, and if we really wanted to deal with the issues and the challenges that our young people are dealing with in having a parent in prison, we really have to do it from the inside out. We have to deal with the shame, the stigma—for so many of the young people, the secret—of having a parent in prison.”

Acknowledging the Secret

Children of incarcerated parents are often told by well-intentioned caregivers not to discuss what happened to their parents. At CPNYC, children are encouraged to share their family histories, and for many children, it is the first setting where they are able to voice their feelings about what happened. “Our model allows them to be able to speak about it, very openly, very comfortably, not only with staff that has been trained to deal with the issues but also with other young people who share very similar experiences,” Content says. Children of incarcerated parents can relate to visiting a parent in a prison several hours away, being searched and separated from a loved one by a glass partition, and getting collect calls from prison—which are infrequent due to cost and caregivers’ inability to afford them. At CPNYC, these experiences do not make anyone different or ostracized.

Anna Morgan-Mullane, CPNYC’s director of mental health, explains, “Being able to bring the children together and provide them with group therapy really opens up an avenue for them to relate to one another, speak comfortably about it, and not just identify but then be able to empathize with each other.” Research by Danielle Dallaire and Janice Zeman of the College of William and Mary suggests that the ability to empathize may be beneficial for children of incarcerated parents, improving their relationships with peers.

“When a young person loses their parent, let’s say to military deployment, divorce, or death, there’s a level of sympathy and compassion that society displays. But that level of empathy does not quite exist when your parent committed a crime.”

Children’s capacity to recognize and regulate their own emotions can also help them overcome the symptoms of trauma. Staff at CPNYC try to foster an environment where the children, many of whom have learned to conceal their feelings, can express themselves freely. At CPNYC, “it’s normal and comfortable to talk about whatever’s bothering you,” Content says. “Because today it might not be that my mother’s in prison. Today the issue might be that I’m pissed off because I miss my mom. And I’m eight years old, and the way that I can demonstrate that loneliness is to beat up the guy who looked at me the wrong way in school today. So it’s being able to walk in and say ‘I’m having a bad day.’ We know what it stems from. Everyone knows and understands what challenges are affecting this child’s life.”

Creating a Safe Space

Since its founding, CPNYC has served over 500 children from more than two dozen neighboring schools, but its beginnings were humble. “Initially, we thought we would just partner with schools, and they would refer our young participants,” Content says. “But when we went to the schools, we probably received about 30 children.” Many schools could not identify which children had an incarcerated parent, in large part because those children and their families did not talk about the fact that family members were in prison.

Fear of being ostracized prevents some families from seeking help, especially from traditional or more overtly clinical settings. One of CPNYC’s aims is to remove the stigma associated with having an incarcerated parent—and with accessing mental health services. Morgan-Mullane explains, “What’s unique about our model in terms of how we offer mental health is through an avenue that feels very safe and normal.” The clinical and after-school staff work side-by-side in the same building. Since the clinical interventions are weaved seamlessly into the program, the children may not even be aware of the expertise and purpose underlying all of the activities they enjoy. To them, CPNYC is just where they go to see their friends, make music, or play ball.

“We understand the services they need, and we have to develop it in a way that’s culturally acceptable for our families,” Content says. “This is a very comfortable way—after-school programming, summer day camp—to be able to accept and receive the mental health services that are needed.”

Serving the Whole Family

While the services at CPNYC revolve around the children’s needs, staff also counsel caregivers and schedule family therapy sessions, in which caregivers learn about the implications of trauma and benefits of cultivating coping skills. Many caregivers have trouble processing their own loss; some show signs of post-traumatic stress disorder or depression, which can negatively impact their ability to care for the children. “If we really want to support the child, we have to support the caregivers,” Content affirms. Although the majority of the caregivers are single mothers, some are grandparents, extended family members, or foster parents. Most face unexpected burdens when the child’s parent is imprisoned.

“Since the clinical interventions are weaved seamlessly into the program, the children may not even be aware of the expertise and purpose underlying all of the activities they enjoy. To them, CPNYC is just where they go to see their friends, make music, or play ball.”

Families impacted by incarceration are likely to be poor, and the incarceration itself can exacerbate the effects of poverty. Often, the parent imprisoned had been contributing the family’s only source of income. During the incarceration, families not only experience additional financial insecurity but also residential instability. A few of the families participating in CPNYC are, or at one time were, homeless. Some are involved in the child protective services system, while others struggle to negotiate psychiatric care or other service bureaucracies. CPNYC advocates for these families wherever appropriate, connecting them to supportive services, attending court hearings, collaborating with school administrators, even helping caregivers write résumés.

CPNYC provides support not only to the children’s caregivers but also to their incarcerated parents, by helping children maintain a connection to them. Staff assist children in writing letters, sending report cards and drawings, and providing transportation to the prisons to visit their incarcerated parents, the majority of whom are several hours away. “Parents write us continuously thanking us for not only still respecting their relationship but encouraging and supporting the bond,” Content says. When family members are released from prison, CPNYC works with the caregivers and children to facilitate the reunification process. All of these efforts are guided and facilitated by the mental health staff and designed to prevent the adverse outcomes so common among these families.

Enabling Children to Heal

Over time, CPNYC’s interventions help children understand the connection between their feelings and behaviors and equip them to more effectively manage their anxiety and aggression. One child, now ten, arrived at CPNYC “so shut down, closed off, guarded, withdrawn, and just sort of disassociated from everything because it was a way of coping that he had learned to go into to be able to protect himself cognitively,” Morgan-Mullane notes. She says it took over a year for this child to be able to talk about how the trauma in his home and surrounding the incarceration of his parent affected him.

“He came to me just the other day when he had gotten into a fight with somebody … and he was like, ‘I’m coming to tell you that I’m angry, I’m not going to hurt this person, I’m just really upset, and I’m supposed to tell you when that happens.’ And we talked through it, he rejoined the group, and that just brought chills to the whole agency. Because this was a kid who didn’t speak when he first came. And he’s giving us full sentences on emotions that he’s having, and feelings that he’s having, and then providing himself with relaxation techniques.” For Morgan-Mullane and her colleagues, this is among the most rewarding outcomes of their work.

Evolving to Meet the Need

CPNYC is still relatively new to their facility on MacDonough Street, having moved there from a smaller site in Bedford-Stuyvesant in March 2014. The refurbished gym, sponsored by the NBA’s Brooklyn Nets, still looks freshly buffed, and Content has yet to decide where to hang all of the children’s drawings and the more than one hundred letters she has received from their imprisoned parents. CPNYC will open a second facility in Harlem in 2015, but Content has plans to expand further, hoping to replicate their model in several other communities. Using data on arrest rates, she and her team can identify the highest concentrations of families impacted by incarceration in New York City—and in other cities and states. “It’s Children of Promise, NYC for a reason,” she says, not so subtly intimating that CPNYC can be rebranded for any neighborhood where it is needed.

How does she evaluate the success of the organization? The progress children make on their treatment plans is certainly one way, but for her, Content says, it is seeing “the young person being able to deal with the issues of the day.” That is no simple feat, and for hundreds of children in Brooklyn, it would not be possible without her.

To learn more about Children of Promise, NYC, visit http://www.cpnyc.org.

Resources

National Transitional Jobs Network, Chicago, IL ■ St. Patrick Center, St. Louis, MO ■ Blue Mountain Action Council, Walla Walla, WA ■ National Health Care for the Homeless Council http://www.nhchc.org/ Nashville, TN ■ M. Burt, L. Aron, T. Douglas, J. Valente, E. Lee, and B. Iwen, Homelessness: Programs and the People They Serve, 1999. The Urban Institute ■ Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP), Child Poverty in the U.S.: What New Census Data Tells Us about Our Youngest Children, September 2013. Retrieved from http://www.clasp.org ■ N. Dunlap, A. Rynell, M. Young, and C. Warland, Populations Experiencing Homelessness: Diverse Barriers to Employment and How to Address Them, 2012. National Transitional Jobs Network ■ M. Henry, A. Cortes, and S. Morris, The 2013 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress: Part 1 Point-in-time Estimates of Homelessness, 2013. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development ■ S. Maguire, J. Freely, C. Clymer, and M. Conway, Job Training that Works: Findings from the Sectoral Employment Impact Study, May 2009. Public/Private Ventures ■ D. Rog and J. Buckner, Homeless Families and Children, 2007. Retrieved from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Human Services Policy ■ D. Rog, C. S. Holupka, and L. C. Patton, Characteristics and Dynamics of Homeless Families with Children (Contract No. 233-02-0087 TO14), 2007. Retrieved from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Human Services Policy ■ J. Trutko, B. Barnow, S. Beck, S. Min, and K. Isbell, Employment and Training for America’s Homeless: Final Report on the Job Training for the Homeless Demonstration Program (Contract No. 99-4701-79-086-01), 1998. Retrieved from the U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration, Office of Policy and Research Web site: http://1.usa.gov/1p1Yx80 ■ U.S. Conference of Mayors, Hunger and Homelessness Survey: A Status Report on Hunger and Homelessness in America’s Cities, December 2013, http://www.usmayors.org

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Guest Voices—

Focusing on the Children: Breaking the Cycle of Family Homelessness

by Daniel Gumnit

The author is CEO and executive director of People Serving People, which provides shelter and other programs for families experiencing homelessness in Minneapolis and Hennepin County.

Each night an average of 365 homeless children and adults stay at the facility operated by People Serving People. Our family shelter, on the eastern edge of downtown Minneapolis, offers 99 emergency housing units. Last year our staff and volunteers assisted more than 3,400 people. Sixty percent of the guests at our shelter are children, with an average age of six.

During my three years as executive director of People Serving People, I have learned that it is impossible to generalize about the causes of family homelessness. Yet it’s clear to me and the shelter’s frontline staff that three main issues are contributing to the drastic increase in family homelessness in Minneapolis and the nation. These issues are (1) the lack of affordable housing, (2) racial and socioeconomic disparities in education and employment opportunities, and (3) the cost of high-quality child care.

This article does not seek to downplay the complexity of these problems or deny that they seem insurmountable at times. In the face of such daunting challenges, however, I believe that if our state and nation are truly serious about breaking the cycle of childhood poverty and family homelessness, we need to focus on at-risk children like those sheltered by People Serving People. This article will describe homelessness in Minnesota, education programs at People Serving People, and the crucial role that executive functioning skills play in the academic, social, and economic success of children. I will also describe our collaborative work with the University of Minnesota’s Institute of Child Development and how the programs we have created build executive functioning skills among homeless children.

Minnesota has made strides in reducing homelessness for veterans and other chronically homeless single adults, particularly in urban areas such as the Twin Cities. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for young children and families who are homeless. In fact, since 2009 there has been a 22 percent increase in the number of two-parent families experiencing housing instability. Children of homeless parents comprise 35 percent of Minnesota’s homeless population, up 9 percent since 2009. Today, 11 percent of students in the Minneapolis Public Schools are either homeless or highly mobile. This means that in an average classroom of 30 children, three are staying in a shelter or have unstable housing.

The root causes for this dramatic increase in family homelessness in Minnesota are systemic. The Twin Cities have one of the tightest housing markets in the nation. The extremely low vacancy rate makes affordable housing nearly impossible to find, and rental rates in Minneapolis have climbed rapidly. The average apartment rent in the city is now $981 per month, up 2.5 percent from just one year ago. Additionally, the disparity in income between whites and people of color in Minnesota is one of the greatest of any state in the union. Sadly, in Minnesota the educational-opportunity gap or academic-achievement gap between whites and people of color is among the greatest of any state as well. Our region’s public transportation system is also ill-equipped to move people living in poverty between their homes and employment opportunities.

People Serving People is Minnesota’s largest and most comprehensive emergency shelter for children and families experiencing homelessness. We not only shelter families, but provide services designed to achieve our ultimate goal of permanently ending a family’s homelessness.

As a frontline human services organization, People Serving People is not in a position to create system-wide changes to increase housing and employment opportunities or reduce educational disparities. Therefore, we focus our efforts on individual families, working to end each household’s homelessness by concentrating on both the short and long term. Our first job is to stabilize the family by addressing the parents’ barriers to housing and providing resources for employment opportunities. In the long term, People Serving People works to break the cycle of homelessness and poverty for the children at our shelter through our educational services, including early childhood development as well as elementary-school-age and teen programs. Our programs for young children are shaped by our collaborative research with the University of Minnesota, aimed at developing executive functioning skills in homeless and highly mobile children.

Executive functioning skills are neurocognitive abilities that include self-control, memory, and flexible thinking, or the ability to adjust one’s behavior based on various demands, priorities, and available options. These skills make it possible for children to voluntarily focus their attention and regulate their behavior to achieve a desired goal. It is vital for children entering kindergarten to possess sufficient executive functioning skills to be able to wait for their turn, listen to the teacher, and follow directions. Many children develop these skills during the preschool years as the brain rapidly develops and they learn to practice self-control. Many children who are experiencing homelessness, however, do not learn these critical skills. Homelessness disrupts the ability of parents, teachers, and other adult caregivers to set up the framework for children to test and develop these skills through consistent routines and structure. In addition, research indicates that fear and anxiety associated with homelessness undermine the development of these skills. In fact, this “toxic stress” produces a hormone, cortisol, that is harmful to brain tissue, including the neural tissue involved in developing executive functioning skills.

Our work with kindergarten teachers has shown us that while teachers appreciate when the children entering their classrooms from our shelter display a head start on literacy, many of them value executive functioning skills even more. In other words, students need to be able to control their attention and behavior first, so that literacy can follow.

Since 1982 People Serving People has collaborated on research, program development, and publications with Dr. Ann Masten, her associates Dr. Stephanie Carlson and Dr. Philip Zelazo, and graduate students from the Institute of Child Development at the University of Minnesota. The researchers conducted studies with boys and girls at People Serving People and found that executive functioning skills assessed during their stay indicated how well these children would do in school. Higher levels of executive functioning skills were a sign that children would perform better academically, enjoy acceptance by other children, display appropriate classroom behavior, and have positive interactions with teachers. Research also showed that scores related to executive functioning skills were more relevant than measures of general intellectual ability (IQ) in predicting many aspects of school success. In addition, there is a growing body of literature contending that executive functioning skills predict lifelong success.

People Serving People’s Early Childhood Development Program (ECDP) began in 2006 as a drop-in center. The vision for the program was to create a model learning center that would foster best practices in child development for highly mobile, high-risk families in transition. The initial drop-in program was developed collaboratively with the University of Minnesota.

Since then, ECDP has matured to include four all-day classrooms for infants and toddlers in addition to preschool prep and preschool that utilize sophisticated curricula focused on the needs of children experiencing homelessness. One of the unique aspects of our work with young children at the shelter is our focus on emotional self-regulation and executive functioning skills. Our teachers also tailor the curriculum to the average shelter stay of 38 days. In 2013 our program was awarded a four-star rating—the highest possible—by the State of Minnesota’s Parent Aware rating system for using the best research-based practices to prepare children for kindergarten.

At People Serving People, we believe that parents are their children’s first and most important teachers. We launched our Parent Engagement Program in mid-2012 with support from the Grotto Foundation to help extend the ECDP’s impact. The program educates mothers and fathers and responds to their questions and concerns about parenting strategies and their children’s development. Support groups and individual sessions with our licensed parent educator increase parents’ confidence in their child-rearing abilities. Mothers and fathers also learn about the executive functioning and emotional self-regulation work our teachers conduct with their children in the classroom and how they can help build on those efforts after they leave the shelter.

As a direct service organization for homeless children and their families, People Serving People focuses on our ultimate goal of permanently ending families’ homelessness. We realize this is an ambitious mission, but the research and education programming conducted at our facility is in line with the intense national focus on helping homeless and highly mobile children develop vital executive functioning skills to increase the likelihood of academic success. I firmly believe that with further study, programs that emphasize executive functioning skills could be implemented nationwide and lead to improved academic and lifelong success for homeless children.

Resources

People Serving People http://peopleservingpeople.org/ Minneapolis, MN ■ University of Minnesota Institute of Child Development, Minneapolis, MN ■ Minneapolis Public Schools, Minneapolis, MN ■ Grotto Foundation http://www.grottofoundation.org/ Arden Hills, MN.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

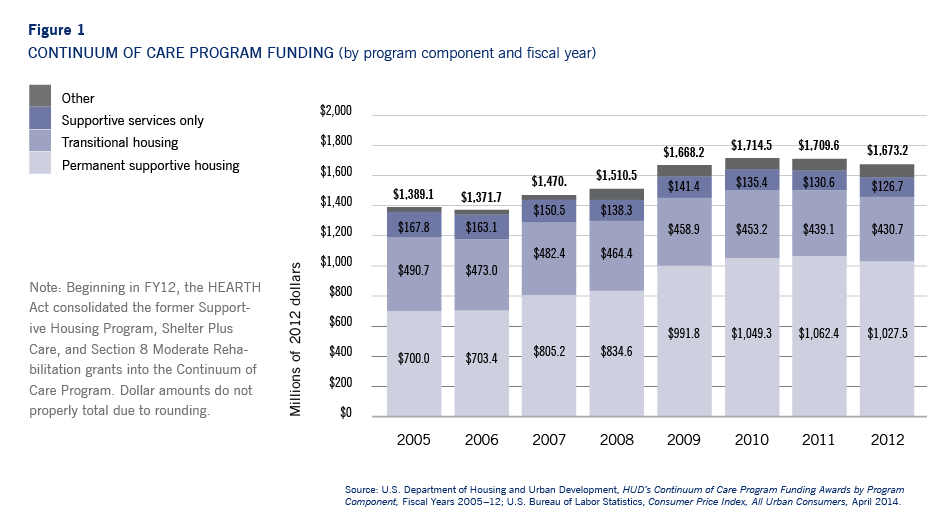

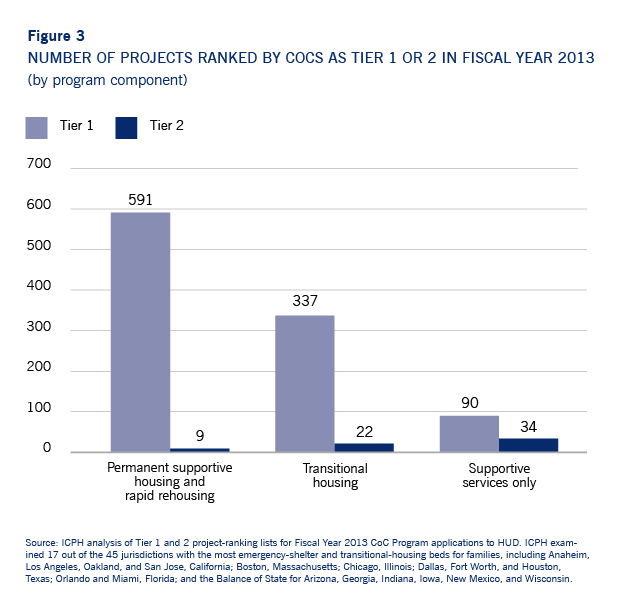

The National Perspective—

Follow the Money: How HUD Influences Services for Homeless Families

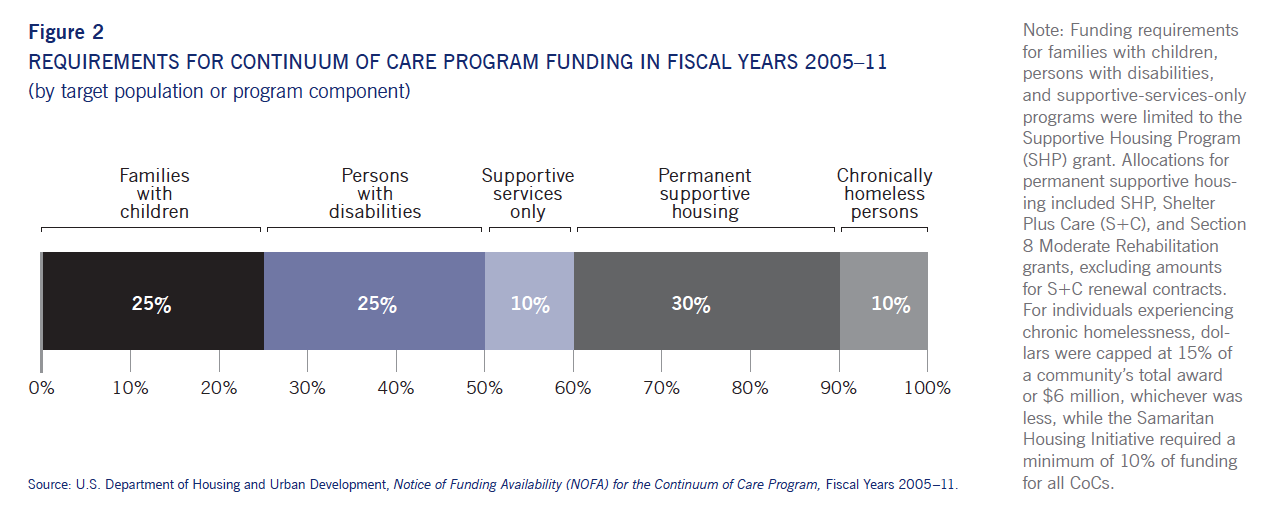

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) affects the way communities deliver services to homeless families through the Continuum of Care (CoC) Program’s competitive funding-application process. To be awarded a share of the $1.4–$1.7 billion annual grant for transitional housing, supportive-service only programs (which provide services such as street outreach or child care but not housing), rapid rehousing, permanent supportive housing, and other projects, communities must submit applications that are scored, in part, according to federal policy priorities determined by HUD. Communities that score higher on their CoC Program applications are more likely to receive funding for their projects.

In order to assess how HUD has shaped public policy to address family homelessness, ICPH examined CoC Program notice of funding availability (NOFA) documents between federal Fiscal Year (FY) 2005 and FY13. ICPH’s analysis found that HUD has given communities few incentives to serve homeless families with children. Instead, the agency has consistently prioritized the conversion of service-rich transitional housing—a model that primarily serves families—into permanent supportive housing for chronically homeless adults and rapid rehousing, two models that emphasize housing over services.