Publisher’s Note

Dear Reader,

The Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness is proud to present the fourth issue f UNCENSORED, marking the magazine’s first anniversary. When we first envisioned the magazine, we believed it would fill a void in coverage of family homelessness and poverty. However, the growth of the magazine and the amount of requests we continue to receive is beyond anything we could have anticipated. We have gone from black and white printing to full color, and have added the “on the Homefront” and “Guest Voices” sections to provide readers with a greater variety of articles and viewpoints. In addition, we now have “Web-extras” which supplement what is printed between the front and back cover.

As we head into the magazine’s second year of publication, we will continuously strive to provide more real-life and hard-hitting stories that illustrate the impact socioeconomic hardships have on families and children in the United States. After you read the magazine, please send your thoughts to info@ICPHusa.org. Your feedback is valuable to us and will influence how we shape future issues. To learn more about ICPH, to forward the magazine to your colleagues, or to request additional copies, please visit www.ICPHusa.org.

Thank you for your continued readership.

Sincerely,

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, Publisher

President and CEO, Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Reaching Youth through Sports: Access to Athletics Improves Outcomes for At-Risk Youth

by Carol Ward

Nearly every weekday after school, hundreds of kids from some of Los Angeles’s most disadvantaged neighborhoods make their way to a community park in the Rampart District to play soccer, or they arrive at one of three area gymnasiums for a basketball practice or game. They are not participants in the city’s leagues for those sports. Instead, they are taking part in some of the myriad of free or nearly free programs offered to poor and homeless youth by Heart of Los Angeles (HOLA) community center.

HOLA, founded more than 20 years ago on the simple premise that “every child deserves a chance,” offers much more than just sports, with after school programs ranging from academic support to cooking to exploration of the arts. But sports are the biggest draw, according to executive director Tony Brown.

Young athletes from Team-Up for Youth learn new soccer skills from their coach, a local university student. Team-Up for Youth’s flagship program, Coaching Corps, trains and places college students and community members in youth sports programs.

Young athletes from Team-Up for Youth learn new soccer skills from their coach, a local university student. Team-Up for Youth’s flagship program, Coaching Corps, trains and places college students and community members in youth sports programs.

Brown says the club initially began as a basketball association geared toward high-school-aged boys who, for whatever reason, could not play on their high school team. “Sometimes it was a lack of parental involvement or transportation issues or even a lack of food,” he says. “We felt those kids really needed adult role models, mentors, and coaches for help not just with sports but with life in general. They needed to learn how to be a good sport, to learn teamwork, cooperation, and hard work.”

The group soon realized that high school sometimes is too late, Brown adds, and expanded its reach to middle- and elementary-age children. And those youth are clamoring for the opportunity to play. “These kids are craving someone they can work with and work for,” Brown says. A participant of SOS Outreach’s SnowCore program enjoys a day skiing at Snoqualmie Summit in Snoqualmie, Washington. SnowCore is an exposure program that provides underserved youth with one- or two-day ski or snowboard trips.

A participant of SOS Outreach’s SnowCore program enjoys a day skiing at Snoqualmie Summit in Snoqualmie, Washington. SnowCore is an exposure program that provides underserved youth with one- or two-day ski or snowboard trips.

Disparity of Opportunity

HOLA is just one of several programs nationwide that seeks to reduce the disparity in access to sports for disadvantaged children. A 2006 study entitled “Play Across Boston: A Community Initiative to Reduce Disparities in Access to After-School Physical Activity Programs for Inner-City Youths,” conducted by the Harvard School of Public Health, found that the ratio of youth to facilities in inner-city Boston was twice the ratio found in medium- and high-income suburban comparison communities. Studies in other cities have shown similar results.

The economic disparity is most evident when it comes to sports such as skiing and snowboarding, where a day’s activity can easily run into the hundreds of dollars. SOS Outreach, headquartered in Avon, Colorado, but with activities in several mountainous areas nationwide, is seeking to bridge that gap. SOS Outreach provides day or week-long trips.

“We partner with 150 or so youth agencies and schools annually,” says Seth Ehrlich, development director, noting that the groups have direct knowledge of which children are most in need. SOS started as a snowboarding outreach society, then added skiing, and later merged with a summer-based organization and now provides year-round activities, including snow sports such as snowshoeing, skiing, and snowboarding as well as rock climbing, backpacking, and seven-day wilderness trips.

The focus is less on kids becoming masters of the sports and more on the social and emotional benefits, Ehrlich says. “We focus our programs on building positive decision making, and we do that through protective factors, such as recognizing within a group positive adult mentorship,” he says, noting the group defines protective factors as conditions that increase the health and well-being of children. Protective factors serve as buffers, helping youth to find resources, supports, or coping strategies that allow them to lead successful lives.

“What we’ve seen is that our participants have higher protective factors than their peers, using a baseline study of schools in Colorado,” Ehrlich adds. “And they have a higher propensity for graduating high school and going on to college than their peers.”

Getting Girls in the Game

Both HOLA and SOS Outreach serve boys and girls, but studies show that among youth living in poverty, girls are less likely to participate in sports than boys. Reasons include cultures that frown on organized sports for girls, at-home expectations for girls, such as babysitting, cooking, and other chores, and a reluctance to participate among some of the girls themselves.

Team-Up for Youth, an Oakland, California-based organization, is attempting to address not only the economic disparity in sports access, but also the disparity in numbers of low-income girls participating in sports compared to boys. Sheilagh Polk, communications program director, says the group’s key goal is to “address the disparity in physical activity for homeless kids and kids of color.”

Certainly not all the kids fall into one of those categories, but Polk says that 75–80 percent of the youth served by Team-Up for Youth qualify for the free lunch program at their schools. The disparities between rich and poor girls accessing sports are evident, the group says. At the city’s Piedmont High School, in a wealthy area, about 70 percent of enrolled girls participate in sports, compared to just 7 percent of girls enrolled in Oakland High School.

Claude Crudup, regional capacity builder for Team-Up for Youth, says the group’s role is to assist schools, city parks, and recreation divisions as well as others in need of robust sports programming. “We’re trying to make the sports programs better so more kids will want to be involved,” he says. Sports programs in the city’s most impoverished areas often do not include any team or competitive play.

“There are many schools that don’t have resources, so we talk to them about setting up leagues so kids can play against other kids, so they can all understand the concept of team sports,” Crudup says. Noting benefits such as providing a voice for participants, and allowing them to learn about participation, skill-building, and safety, Crudup says, “We stress that if we improve these areas, those programs will be doing a lot for kids.”

A child enjoys a game of lacrosse after school. Team-Up for Youth creates after-school sports opportunities for girls and boys that build their confidence and skills.

A child enjoys a game of lacrosse after school. Team-Up for Youth creates after-school sports opportunities for girls and boys that build their confidence and skills.

Sports Hook Kids In

Many of the sports programs geared toward children living in poverty are, by choice or necessity, much more than sports programs. Take, for example, the Youth Impact Program (YIP), a program started originally in Washington, D.C., by Riki Ellison, a ten-year veteran of the National Football League (NFL) and three-time Super Bowl champion. YIP targets at-risk middle school boys who live in inner cities, leveraging their interest in football to take them off the streets for five weeks in the summer. Boys attend a free day camp on a college campus, where they not only play football but also take part in academic programs.

“I was a kid like those kids, from a single-parent home,” says Ellison. The participants, all 9- to 12-year-old African-American and Hispanic boys, need far more than just football instruction.

“Most of our kids are below the poverty line, so we address their food needs,” Ellison says, adding YIP quickly realized those needs are most acute during summer when school is not in session. “We address their summer school needs, because most of these kids are not at the levels they should be. Forty-eight percent of the kids we serve have never read a book, so we’re addressing those concerns.”

YIP works through universities around the country, which help in hiring staff and utilizing student athletes as mentors. They then scour local schools for eligible participants. “We’ve never had a problem getting kids,” Ellison says, noting that the program serves about 200 boys each year, many of whom would not normally be taking on a rigorous academic schedule during their summer break. “It’s a volunteer program so the kids have to want to do it, but the alpha males tend to be attracted to a program that has the sexiness of the NFL behind it.”

Young athletes from Team-Up for Youth learn how to dribble and shoot on the basketball court. Team-Up for Youth seeks to increase the number of low-income girls who participate in sports.

Young athletes from Team-Up for Youth learn how to dribble and shoot on the basketball court. Team-Up for Youth seeks to increase the number of low-income girls who participate in sports.

SOS Outreach also uses sports as an avenue to influence more than 5,000 at-risk youth annually. “The sport is just the hook,” admits Ehrlich. “We now offer a program where for every day of activity they’re going to do an equal day in the community, focusing on service projects or development classes or resume writing or maybe an internship as they get close to graduating high school and going on to college. We want them to feel they can make a difference and see themselves as part of the community.”

Resources

Heart of Los Angeles (HOLA), Los Angeles, California: www.heartofla.org ■ SOS Outreach, Avon, Colorado: www.sosoutreach.org ■ Team-Up for Youth, Oakland, California: www.teamupforyouth.org ■ Youth Impact Program, Alexandria, Virginia: www.youthimpactprogram.org.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Employment Challenges: Safety Net, Training, and Understanding—All Crucial to Getting and Keeping Jobs

by Carol Ward

Five years ago Jessica Hill was a statistic. Today her successes are numerous. She never dreamed she would be a college graduate much less a small business owner. The young woman from Mississippi bore two children while still in high school, and at age 17 moved out of her parents’ home and into subsidized housing. She worked at a fast food restaurant but remained on public assistance, as the pay was inadequate to support her family.

Hill, who became involved with a man who was abusive, says she felt like she did not have any options. She says abusive relationships “happen to a lot of young women with children who are living in poverty. We think we have to settle,” Hill says. “Our Southern heritage makes many feel they have to stay and hope things get better.”

Hill stayed for a while, through a couple of other failed jobs and another baby, before finally finding the courage to make a change. She sought financial assistance and enrolled at the state university, graduated, and now runs her own business from her home. “Where I come from, we don’t get to do that, only white people do that,” Hill says, still incredulous at her turn in fortune.

“I used to be known as the girl who came to work in sunglasses to hide a black eye, who used to have an attitude because I was so unhappy with my life,” she says. “Now I know that people in poverty can succeed if they really grasp the training and help that is available, learn how to be a professional and learn to be a team player. I’m now trying to set the example of an independent, successful woman.”

Her story is not unusual, but for every successful climb out of poverty there are dozens of failed attempts. It takes an extraordinary amount of perseverance, usually coupled with training and assistance from others, to break out of the cycle.

“One common thread is that there is no hope,” says Sharon Taylor, director of operations for the Evansville Christian Life Center. “These people are so busy trying to survive and get food for their kids that they have no way to plan for the future.”

Philip DeVol calls it “the tyranny of the moment.” DeVol, an author on poverty issues and consultant for the Aha! Process, says that living in poverty is so stressful that people bury their dreams and just try to make it through the day. “When you’re so busy trying to solve concrete problems, that’s what you spend all your time doing and you lose track of your future orientation, lose track of your goals,” he says.

A job seeker fills out a job search application at Cincinnati Works. This organization pairs up unemployed or underemployed individuals with employers looking to fill entry-level positions in an effort to eliminate poverty in and near Cincinnati.

“Why Don’t They Just …”

Those goals often revolve around getting, and keeping, a job that allows a person to earn enough to support himself and his family, with perhaps a bit left over at the end of the month. The question, “Why don’t they just get a job?,” is uttered in some form or another by those in the middle and upper classes who have little understanding of the barriers to employment often faced by those living in poverty.

While each individual situation is different, service providers say there are some common threads inhibiting those in poverty who want to work from finding sustainable employment.

“One of the biggest challenges is transportation,” explains Nakiya Kirton, director of community relations and marketing for Cincinnati Works, noting that the group’s clients are taking part in job skills training and employment counseling by choice and are highly motivated to work. “There are also those who have housing challenges, people who have legal barriers, even if it’s something as small as a misdemeanor. Or it can be something as simple as child care. Then there are things like coping skills, time management, and life skills.”

In Evansville, Indiana, Taylor says lack of comprehensive public transportation is the single biggest obstacle to connecting people in poverty who want to work with the jobs available in the region.

“People are always saying, ‘Well, there are jobs available,’ and sure there are,” Taylor says. “There are some higher paying jobs just north of our community, factory jobs that offer benefits. They are entry level jobs that require a skill set that people in poverty could learn, but they work factory shifts and people can’t get to work.”

There may be jobs available in certain communities like Evansville, but opportunities are hard to come by in many other parts of the country. “With soaring unemployment rates there are far more job seekers than there are jobs,” points out Suzy Epstein, managing director of jobs and economic security for New York’s Robin Hood Foundation, which targets poverty by funding job training programs.

The reality is the current economy has made it more difficult for people living in poverty to compete for any positions that are available. “Ever since the fall of ‘08 a whole bunch of middle class and working class people have slipped into institutional poverty,” says DeVol, noting those who have lost jobs or fallen victim to the economic crisis. “The labor pool is absolutely packed with people who want to work, and the people who were struggling to get and keep jobs in the first place are now forced into that L-shaped poverty.

We’re returning to the idea of the ‘undeserving poor,’” DeVol continues. “Instead of having sympathy for the people at the bottom of the economic ladder, there is more criticism because there is sympathy for people in institutional poverty.”

One Crisis Away

Once people living in poverty get a job, it is often difficult to keep it. For the average salaried worker, a day missed due to outside circumstances usually does not have any real repercussions, but for those working entry-level jobs, it can mean loss of a crucial day’s pay, or even loss of a job.

“When everything around you is breaking down, whether it’s the housing you’re in or child care or something else, it’s difficult if you don’t have resources to solve problems,” DeVol says. “Poverty is very stressful, so there is lots of illness and that interferes with going to work. When your car breaks down, that interferes. All those things mean it’s much harder for you to get to work every single day.”

Epstein agrees that the rate of job retention can be frustratingly low. “We’ve found that many people can get a job but not everybody can keep a job,” Epstein says. “Several elements make things crumble. For folks with histories of addiction and mental illness, there is substance abuse and relapse. At the other end of the spectrum, child care can be a huge issue and make it hard to keep a job. The first affects men more and the second affects women, but we see a lot of job losses because of these.”

And sometimes the job losses are just a function of the economy. Joyce Lavery, executive director of the Safe Haven Family Shelter in Nashville, says she has seen a lot of job loss in her community simply due to the economic crisis. The impact is worst when people have no place to turn.

“The biggest criteria I see with families that are homeless is that they do not have any kind of support system,” Lavery says. “They’re one crisis away from becoming homeless, and when that crisis happens—like a job loss or a medical emergency—they have no place to turn.”

A young woman who became successfully employed through Cincinnati Works. The program places more than 600 people annually with a high rate of retention.

A young woman who became successfully employed through Cincinnati Works. The program places more than 600 people annually with a high rate of retention.

Creating a Network

Several programs and agencies are turning their attention to helping people create

that network of people they can rely on in times of crisis. Move the Mountain Leadership Center has a goal of ending poverty nationwide. One initiative is its Circles Campaign, which pairs families working to

get out of poverty with “allies” from the community who are willing to befriend and support the family through the process.

Karin VanZant, national Circles coach, says the program simply provides a platform for local service providers to connect with each other as well as influence decision-makers on the issues facing people living in poverty. “Circles doesn’t provide any of the services,” she says. “We just help with the connections and the network and the way to discuss what the needs are and how those needs can be matched with the resources, without replicating or competing with any existing programs going on in the community.”

Kirton of Cincinnati Works also says the network of support is crucial. “When they don’t have a network of their own—whether it be support from family or close friends—that’s where some of our key partners come into play,” she says, mentioning, for example, a child care facility partnership that will allow temporary or occasional placements of children whose regular child care has fallen through.

The goal is to “develop the mindset of longevity on the job,” Kirton says. It may not be the ideal job, or even a good job, but sticking it out through the rough patches proves to employers that they are committed to being employed.

“Once we have helped them create that stability, then we can look at what’s keeping them from moving forward,” Kirton adds. “It may require a skill set, or simply brushing up on interview skills. We help them work towards their goal and pull themselves out of poverty.” ■

When It Doesn’t Pay to Work

A report released in October 2008 by the Working Poor Families Project found that 28.2 percent of American families with one or both parents employed were living below 200 percent of poverty, identified as the “working poor.”

The report, “Still Working Hard, Still Falling Short,” found that 9.6 million families lived at that level, including more than 21 million children in 2006. In 13 states, 33 percent or more of working families were low-income, and in 13 states, 50 percent or more of minority working families were low-income. The report also found that nationally, 22 percent of jobs paid wages that fell below the federal poverty threshold.

The report noted that working poor families “lack the earnings necessary to meet their basic needs—a struggle exacerbated by soaring prices for food, gas, health, and education.”

About 60 percent of low-income working families were forced to spend more than one-third of their income on housing, and nearly 40 percent lack health insurance for one or both parents.

Such data give credence to the idea that sometimes it just doesn’t pay to work. A 2006 study entitled “When Work Doesn’t Pay, What Every Policymaker Should Know,” conducted by the National Center for Children in Poverty, illustrates the difficulty. “To assist low-wage workers and their families, the federal and state governments provide a set of ‘work supports’—benefits such as earned income tax credits, child care subsidies, health care coverage, food stamps, and others,” the report notes. “Those benefits are means-tested, so as earnings increase—particularly as they rise above the official poverty level—families begin to lose eligibility even though they are not yet self-sufficient.

The result is that parents can work and earn more without their families moving closer to financial security.”

A project entitled “Making Work Supports Work,” also published by the National Center for Children in Poverty in February 2010, makes a similar argument. Noting that while work support policies vary across states and localities, patterns are generally similar.

“To better reward and encourage employment, reforms are needed to expand access to benefits by increasing eligibility limits and covering more eligible families; phase benefits out more gradually to soften or eliminate cliffs; and pay attention to program interaction so that families don’t lose multiple benefits at once,” the paper advises. “With these strategies, policymakers can create a work support system designed to truly make work pay.”

Resources

Evansville Christian Life Center, Evansville, Indiana: www.restoringpeople.com ■ Cincinnati Works, Cincinnati, Ohio: www.cincinnatiworks.org ■ Robin Hood Foundation, New York, New York: www.robinhood.org ■ Safe Haven Family Shelter, Nashville, Tennessee: www.safehaven.org ■ Move the Mountain Leadership Center, Albuquerque, New Mexico: www.movethemountain.org.

When It Does Not Pay to Work

“Still Working Hard, Still Falling Short,” (2008), The Working Poor Families Project: www.workingpoorfamilies.org/pdfs ■ “When Work Doesn’t Pay, What Every Policymaker Should Know,” (June, 2006), National Center for Children in Poverty, New York, New York: www.nccp.org/publications.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Viewing Homelessness through a Lens: Documentaries Capture a Reality Words Cannot Explain

by Stephanie Harz

Three newly released documentaries examine the lives of homeless families and youth. They are a reflection of the times, highlighting the increase in the number of homeless families throughout the United States. In the 2009 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress (AHAR), the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development indicates that the number of families in shelter has increased by 77 percent, from 131,000 families in 2007 to 170,000 in 2009.

Unfortunately, this increase comes at a time when resources and funds for homeless services are decreasing, leaving the homeless with little, if any, assistance. Of the 29 cities included in the 2009 Hunger and Homeless Survey conducted by the United States Conference of Mayors, 22 cities, or 82 percent of respondents, reported having to make adjustments to accommodate an increase in the demand for shelter, and 14 cities, or 52 percent of respondents, reported they had to turn away homeless individuals and families because of lack of available shelter beds. But the numbers are not sufficient in telling the story. An escalating number of families are sleeping in churches, motels, and in friends’ homes.

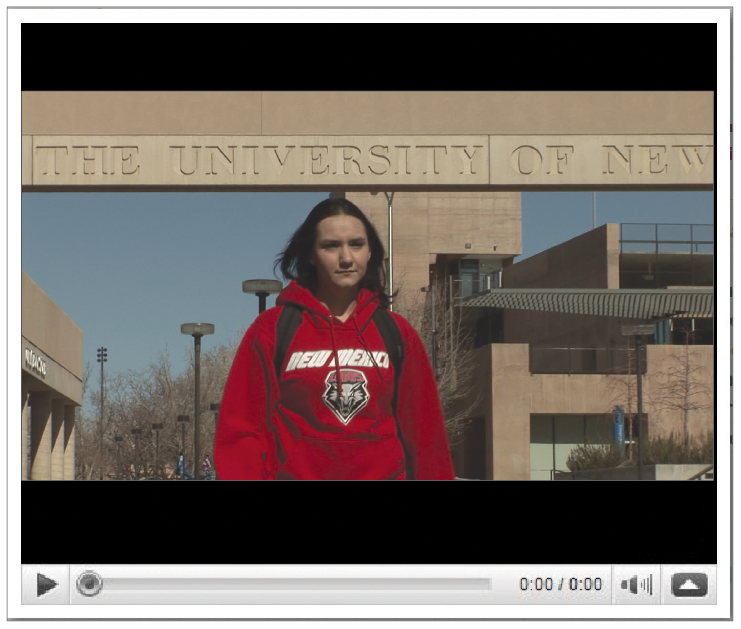

A video still from Looking In: Kids Who Are Homeless. Rachel Kindell, a formerly homeless youth at the University of New Mexico where she is currently enrolled in her sophomore year.

A video still from Looking In: Kids Who Are Homeless. Rachel Kindell, a formerly homeless youth at the University of New Mexico where she is currently enrolled in her sophomore year.

Familiar Stories Become Startling Truths

The New Mexico-based documentary, Looking In: Kids Who Are Homeless, directed and produced by Christopher Schueler, exposes the usually secret lives of homeless youth. The movie explores the lives of six homeless teens as they share their disappointing past, uncertain present, and hopeful future.

The issue of youth homelessness is also investigated in the documentary The Hidden Homeless, directed by Dean Thomas and produced by Eileen Littig of the Education Television Productions of Northeastern Wisconsin (ETP-NEW). Viewers meet homeless youth from Green Bay and Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and Manistique and Escanaba, Michigan, where the teens show how they survived day-after-day without anyone knowing they were homeless.

Shifting the focus from homeless youth to homeless women and families, On the Edge follows seven women who struggle to stay off the streets. Situated in suburban towns, rural areas, and resort communities throughout the country, these women deal with abuse, drugs, and natural disasters. They each tell their unique stories that ultimately lead them to the same place: life without a home.

For Diane Nilan, producer of On the Edge and president and founder of HEAR US Inc., it was obvious that a video documentary was the next step in increasing awareness of this growing problem. “We are a very visual society,” Nilan says, “I wanted the women to tell their story on their own; to give them their voice and visibility, which is the cornerstone of HEAR US.”

An organization that advocates for systemic change for homeless families and youth, HEAR US believes this increasing population has been ignored for far too long. Nilan says, “When done well, a documentary can be very successful at advocating for an issue. By the women telling their own stories, rather than someone else telling them, a stronger message comes across.”

Angela from Opelousas, Louisiana, explains in On the Edge how she lived in a trailer with her seven children for four months without utilities. The Department of Children and Family Services threatened to take her children and place them in foster care if the utilities were not turned on within one week. Desperate to keep her children, Angela went to a family homeless shelter. Now, three years later, she is a director at the homeless shelter where she and her children stayed.

Melissa, another woman featured in On the Edge, lived in Milton, Florida, when her daughter became very sick, causing Melissa to miss work and ultimately be fired from her job. Unable to pay her bills, she was evicted and she and her children spent the next three years living in multiple hotels and in friends’ homes. When Melissa finally was able to afford a home, she and her family only lived there for six months before a hurricane destroyed their apartment.

Schueler agrees with Nilan’s view of documentaries as a tool to promote awareness and advocacy. Schueler states, “Through honesty, we can tell a story in a way that helps social agencies and groups make change in a responsible way.”

He makes it clear in Looking In that the rise in the number of homeless youth is a severe problem in New Mexico. In the 2008–09 school year, New Mexico had 8,380 homeless youth enrolled in public schools, an increase of 91 percent since the 2006–07 school year when there were 4,383 homeless youth.

Looking In was designed as a comprehensive media campaign to help parents, educators, and communities in New Mexico understand why homelessness occurs and to address how it relates to education. The documentary shows how school is often the only consistency in homeless teens’ lives. They do not sleep in the same place for a long period of time and often live by themselves, leaving them lonely and without adult guidance. School provides homeless youth with a stable place to come to day after day, where they are indoors and looked after by adults. Despite this connection to school, homeless teens often do not inform their teachers or school administrators of their living situation, making it much harder for schools to identify homeless students and provide them with the services to which they are entitled.

Tyler Booher, one of the teens featured in Looking In, found his mother, Janet, lying on the floor badly beaten by her husband. Janet filed a restraining order against her husband and she and Tyler moved out of their home. With nowhere to turn, they started sleeping next to a dumpster behind a McDonald’s. At only 15 years old, Tyler begged for spare change or for something to eat on the street. Another teen in the documentary, Miranda, was 16 years old when she and her father were evicted. Her classmates made fun of her for wearing the same clothes every day.

The high schools in Green Bay, Wisconsin, like those in New Mexico, are also experiencing a drastic increase in homeless youth. As of November 2010, there were 800 homeless high school students in the Green Bay area. This is more than double the 325 homeless high school students that were enrolled in 2004. The Hidden Homeless shows these youth looking much like their non-homeless peers, yet living on their own and sleeping wherever they can find shelter, including an abandoned bus and a tent on a deserted island.

Scott, an unaccompanied youth featured in The Hidden Homeless, left his abusive home when he was 18 years old and went to a small island on Menominee River, where the states of Wisconsin and Michigan meet. Scott describes the island as the only local, semi-livable place where he could live without being seen by anyone in the community. He stayed on the island for a little over a week, until he knew he would freeze, relocating then to a laundromat.

Unlike Looking In, where some homeless youth live with their parent(s), The Hidden Homeless features only unaccompanied youth, homeless youth who are not in physical custody of their legal guardian and, according to the National Center for Homeless Education, have often left home because of family conflict, where they are forced to leave home by their parents or choose to leave because they feel unsafe or unwilling to continue living with their parents. In addition, Looking In is geared primarily toward an audience of educators, policy makers, and those who work with homeless youth. The documentary aims to alleviate youth homelessness in New Mexico, noting solutions and supports to assist homeless youth. In contrast, The Hidden Homeless is geared toward a general audience and is less about solutions to youth homelessness and more about providing insight into what takes place in the lives of homeless teens.

A picture taken while filming On the Edge. The women in the documentary were interviewed in a variety of settings, including their work places, homes,and previous shelter placements.

What It Takes to Tell a Story

Wisconsin Public Television aired The Hidden Homeless, and in November 2010 the film won the “Outstanding Media Presentation Award” by the National Association of the Education of Homeless Children and Youth. However, the process for creating this influential documentary was neither simple nor short. The filming did not begin until the teen cast members trusted and felt comfortable with Thomas and his crew. “We did not do any filming during the first six months,” explains Thomas. “It took a long time to build trust with the kids and their social workers. It is very difficult to build the trust. If you don’t build the trust you get yes and no answers.”

This slow process of building trust is not unique to Thomas and his crew. Schueler went through a similar process when creating Looking In. “We don’t bring huge lights; that’s intimidating. We try to keep [the teens] in an element where they are comfortable and they feel safe,” Schueler explains.

Schueler’s efforts were apparent in the end product. Looking In has been distributed to every parent-teacher association, superintendent, and health teacher in the state of New Mexico, and the documentary has been aired on various television channels throughout New Mexico.

Rachel Kindell, a teen featured in Looking In, is now a sophomore at the University of New Mexico. The film begins with her explaining she was raped by two men when she was 14 years old. She attempted to commit suicide soon after. Her mother’s boyfriend said she was lying about being raped and acting out for attention and kicked her out of the house when she was 15 years old. All she had was her car and a few belongings. Kindell lived in her car or slept on friends’ couches until her senior year of high school when she was able to pay rent to live in a house.

Creating the documentary did not make Kindell uneasy, but seeing it was a different experience. “It was a little more difficult to watch it than it was to be a part of it. When you talk about it, it’s different from hearing it,” she explains.

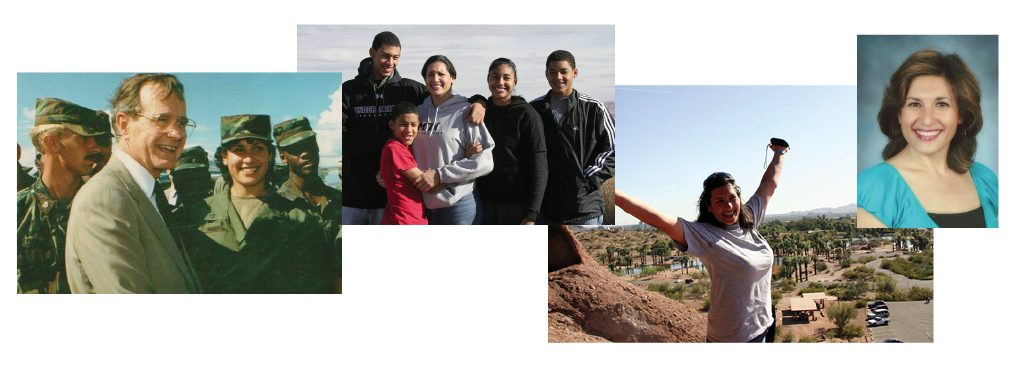

Julianna Martinez, from Phoenix, Arizona, had different feelings when being interviewed for On the Edge. A mother of four and formerly homeless because of spousal abuse, Martinez was surprised by the issues she shared with others. “I was very nervous at first. As we started to go it just came out.” She continues, “When Diane interviewed me the first time I was homeless, I was coming to terms with what I was going through. We both found out more than we thought we [would].”

In On the Edge, Martinez explains how being the victim of domestic violence left her feeling physically and emotionally trapped in her home, unable to leave her husband and support herself and her children. Her husband made her feel so insignificant for such a long period of time; she did not believe she had the ability or courage to leave. Both Martinez and her ex-husband were in the military when the abuse began. Martinez remembers how apprehensive she was to tell anyone about what was taking place because she knew her husband would lose his military rank, which would cause his salary to decrease making them unable to afford their home and provide for their children.

She was raised to believe that children need both a mother and a father. “I thought I was protecting my children by staying, but my kids knew what was happening,” she says. It was not until her husband became violent with her eldest son that she made the decision to leave.

Personal snapshots provided by Juliana Martinez, a formerly homeless mother featured in On the Edge. From left to right: Juliana with former United States President George H.W. Bush while she was serving in the U.S. military, Juliana with her four children who were 7, 9, 11, and 13 years old when they became homeless, Juliana enjoying a hike in Arizona, and a recent portrait.

Personal snapshots provided by Juliana Martinez, a formerly homeless mother featured in On the Edge. From left to right: Juliana with former United States President George H.W. Bush while she was serving in the U.S. military, Juliana with her four children who were 7, 9, 11, and 13 years old when they became homeless, Juliana enjoying a hike in Arizona, and a recent portrait.

Wanting Others to Know

Martinez speaks publicly about being homeless because she believes “kids don’t deserve that life.” The local family shelters would not accommodate Martinez’s teen children. In order to keep the family together they stayed in their friends’ homes. “After we left the house the kids just stayed in school. They went to camps in school,” says Martinez. “At one point we had to all stay with different friends. We had a rally point on the football field. Whatever your situation is, you can come out of it. Ask for help.” Now with two of her children in college on basketball scholarships, Martinez wants other people to know what she did not: there are resources and people that can help homeless families.

Kindell also has a personal message that she hopes she got across in Looking In. “When I got kicked out [of my house]. I fell on a wrong path: gangs and drugs. I just kind of looked at myself one day and thought I could go down the hard road and figure things out, or I could die getting shot or overdosing,” explains Kindell. “A year and a half later I got a scholarship and went to a conference in D.C. and spoke about my story. This was two years ago, and then what I said began getting published in the newspapers and people found out what was going on. I went to West Mesa High School; they called me their homeless student. At first it kind of bothered me, but after a while I was kind of proud of it. It kind of defines me.”

Kindell is open to discussing her homeless years, because she wants teens who are currently homeless to know they are not alone. In describing homeless teens she says, “They experience fear. They need help but they are afraid to ask.”

Scott left his home in Chicago, Illinois, to escape gang involvement. Having no connections in Escanaba, Michigan, Scott, and another youth from Chicago, slept in an abandoned school bus located in the woods.

Stories with a Purpose

These three documentarians do not consider their work a success unless it informs their viewers of the issue at hand and encourages a reaction. “We are looking for any response we can get,” Thomas explains of his documentary, The Hidden Homeless. “When people are aware of the problem, they start thinking about it. We all know spending is shrinking and shrinking and things are getting cut,” he adds, “Whether they take an active role or passive in their vote, they can help.” Thomas wants The Hidden Homeless to inform people in Wisconsin and Michigan of the recent increase in unaccompanied youth. He believes once people are informed of the issue, they will take the action they deem most appropriate.

Schueler had more specific goals when he began creating Looking In. “We created four think tanks to determine how the documentary can best address the problem and a solution. We included government officials, public education teachers and administrators, public health advocates, non-governmental agencies who work with the homeless, doctors, homeless people, and others involved with homeless youth,” explains Schueler. The think tank meetings and other forms of research were conducted for a year before the filming began.

Looking In advocates for an increased amount of affordable, safe housing in New Mexico. “We strategically placed the Supportive Housing Coalition at the end of the documentary. Throughout it we wanted to grab people by the heart with the kids, explain the issue. Then see what is possible at the end, give specific solutions,” says Schueler. In addition to promoting additional affordable housing, he states, “The goal in New Mexico is to end homelessness, certainly child homelessness, and I think we can do it.”

Kindell says, in Looking In, that the hardest part of being a homeless teen “was knowing that nobody was there that I could talk to. Sometimes I got these feelings like I just wanted to break down and cry, and who did I have to turn to, nobody. That was probably the worst part of it all, not being able to share something with anybody.” Kindell’s story and the stories of others featured in these documentaries make homelessness personal, taking on the face of the teenager, mother, or family next door, and creating a powerful tool for change. Unclear or misguided ideas about homelessness become stark realities in these films, making teen and family homelessness an issue impossible to ignore.

Resources

HEAR US Inc., Naperville, Illinois: www.hearus.us ■ Christopher Productions, Albuquerque, New Mexico: www.christopherproductions.org ■ Educational Television Productions of Northeastern Wisconsin, Green Bay, Wisconsin: www.uwgb.edu.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Finding a Way Back Home: Families Struggle as Aging Parents Face Homelessness

by Joan Oleck

photographs by P.J. Heller

On Christmas Eve 2009, Kent Vernon Scott sat down in front of his computer and began an online search for his aging dad.

“I stayed up, determined,” the 47-year-old Roswell, New Mexico, computer businessman recalls. “No one else had given me any help. In 23 years, I had never heard a word from him.”

Scott even asked the FBI for help finding his now 75-year-old father, Delbert Dean Scott. But the elder Scott was un-findable. Unbeknownst to his two grown sons and daughter, he had become homeless in 1999 after losing everything he had while caring for his dying wife.

After suffering a series of strokes, Louise Scott lay paralyzed in an ocean-view condominium, staffed by a full-time nurse. “We communicated with our eyes,” the loving husband remembers of those last sorrowful weeks before Louise died. Unfortunately, the insurance company refused to pay for her care, which consumed all of Delbert’s resources. He had just $78 in his wallet when he arrived at the Howard Street shelter where, he says, he slept “toe to toe” with dozens of other homeless men for several years. He had fallen very far from his once-affluent life as a successful San Francisco jeweler, with investment properties in his portfolio and private school for his kids. Never resorting to alcoholism or drug use, Delbert persevered despite his troubles. When his jewelry business floundered and his bills piled up, it was his ego and stubbornness that caused him to withdraw from his children. “I had a little problem called egotism,” Delbert confesses, voicing the reluctance that many seniors have to not be a “burden” on their children. “I didn’t have the audacity to share with them my newfound poor life,” he says. So, for ten years, he kept it a secret and faded away.

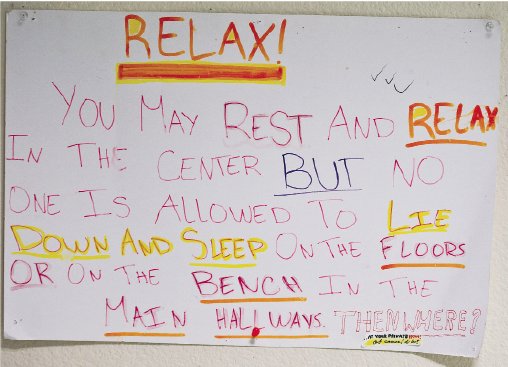

A makeshift sign on the bulletin board at the Canon Kipp Senior Center reminds clients that they cannot sleep on the floors of the center. The center is a gathering place for many of the homeless and formerly homeless elderly in San Francisco.

Delbert is among millions of impoverished seniors in America today, whose numbers are expected to rise given the current state of the economy, government threats to raise the age for social security eligibility, and the first wave of baby boomers turning 65 this year. The elderly population (65 and over) is currently 12.6 percent or 37 million. With the aging baby boomers, that number is expected to double by 2050.

In contrast to Delbert, though, many Americans choose to live in multigenerational homes. According to a Pew study, multigenerational households today are home to 20 percent of Americans 65 and older. A companion study from the Pew Research Center reported that a majority—56 percent—of the public considered it a “family responsibility” for adult children to take an elderly parent into their home. In 2008, a record 49 million Americans lived in households with two adult generations (or a grandparent and at least one other generation), an increase of 2.6 million Americans from 2007. There is an ethnic divide in multigenerational housing. Hispanics (22 percent), blacks (23 percent), and Asians (25 percent) are significantly more likely than whites to live in a multigenerational household.

Yet the impetus for this trend remains unstudied. “We know that it’s happening and we can compare it over time,” Richard Morin, a senior editor at Pew, says of the multigenerational findings. “We don’t know what’s happening within the family: whether they’re welcoming grandma and grandpa back home, or what pressures this may be causing, or even why it’s happening. Is it because they lost the homestead and have to live with the kids? Or did they do this in lieu of entering a senior facility they couldn’t afford? Those are the wonderful questions I wish we could answer.”

The crisis in senior housing is belied by the fact that, compared to families with children, seniors have been relatively well off during the current economic recession. “Relatively” is a word researchers frequently use to describe seniors’ economic status. While the national unemployment rate is 9.6 percent, the rate among workers 55 and older is 7.6 percent. Nevertheless, 7.6 percent is still concerning since older workers tend to remain unemployed far longer than younger workers.

While the number of Americans in poverty in 2009 was the highest it has been in 51 years of census data, the proportion of seniors in poverty actually dropped. 8.9 percent of people over 65 had annual incomes below the poverty threshold of $10,326 for singles and $13,030 for couples, roughly 3.4 million seniors—not huge, relatively speaking. Those numbers would be much higher without the help of Social Security and Medicare benefits.

Eli Glasper, 72, (left) and Bobby Bogan, 69, watch TV in Glasper’s tiny one-room apartment, which is about 120 square feet and includes a small kitchen and bathroom. Both men are members of Seniors Organizing Seniors, an advocacy group made up of formerly homeless men and women.

Eli Glasper, 72, (left) and Bobby Bogan, 69, watch TV in Glasper’s tiny one-room apartment, which is about 120 square feet and includes a small kitchen and bathroom. Both men are members of Seniors Organizing Seniors, an advocacy group made up of formerly homeless men and women.

Any consideration of senior financial security must consider medical spending (which, for 55- to 64-year-olds, is twice that of 35- to 44-year-olds) as well as financial stability. A recent University of Michigan study found that people 65 and over are the fastest-growing segment of Americans declaring bankruptcy.

The relative issue is again at play when considering data on homeless seniors. The Department of Housing and Urban Development in 2009 reported that the incidence of overall sheltered homelessness was 50 per 10,000, but for seniors 62 and over it was 1 per 10,000. So, again, seniors were and are “relatively” better off.

Regardless, the increase in the senior population likely presages, at best, more multigenerational families and, at worst, more senior homelessness. Indeed, the National Alliance to End Homelessness has predicted that senior homelessness will increase by one-third by 2020 and more than double by 2050. There are plenty of reasons why. One is a serious lack of subsidized housing for the present, much less the future. HUD Section 202 Supportive Housing for the Elderly Program currently provides only 300,000 units of affordable housing. AARP estimates that there are approximately ten waiting seniors for every vacancy. And a Congressional report, “A Quiet Crisis in America,” has said that 730,000 units need to be constructed by 2020 to deal with the demand.

That effort will be daunting. Diane Beedle, a senior legislative representative with AARP, ticks off the other indicators of the coming senior housing crisis. “You combine [the fact that] the 50-plus population are more unemployed and stay unemployed longer; you add the housing crisis; you add the potential loss of all these units; you add the loss of home equity combined with limited retirement savings,” she says, “and we’re going to see a ‘perfect storm’ created for causing more housing problems.”

There are regional differences for seniors facing housing stress. Sara Peller, associate director of programs at Dorot, a seniors service organization in New York, points out that “in New York it’s particularly a problem because of space.” She describes a homeless senior she knew who was being housed by Dorot’s Homelessness Prevention Project at the same time she was eating supper each night in her daughter’s studio apartment.

The upside of housing in New York, says Patrick Markee, senior policy analyst for the Coalition for the Homeless, is that the city hosts the largest rent regulation system in the country. Indeed, Markee says, “More low-income people in New York City live in rent-stabilized housing than live in subsidized housing. And half of all rental housing is stabilized.”

The picture is brighter across the country in Cleveland, where seniors with housing stress are being quickly rehoused, according to Brian Davis, executive director of the Northeast Ohio Coalition for the Homeless. Stimulus money contributed $14 million to the city’s Department of Aging to intervene against senior homelessness. “For those over 55, we can get them into housing within three months; those over 62, we can usually get them in within a month,” Davis says proudly. In Cleveland too, where there is a “huge foreclosure issue,” collaboration is the new rule. A senior facing a housing problem will be visited from a member of the Department of Aging, not the Housing Department, and will receive help intervening with the landlord or bank.

On the West Coast, San Francisco faces the unusual problem of serving a large number of HIV/AIDS housing-stressed seniors who never thought they would survive so long. According to James Chionsini, a staffer at the Planning for Elders in the Central City agency, “A very common thing was people thought, ‘Well, that’s it,’ so their savings, their money, they spent it. They said everything they wanted to say to everybody in their life, but what do you know? They got the meds and now they’re out riding their bicycles!”

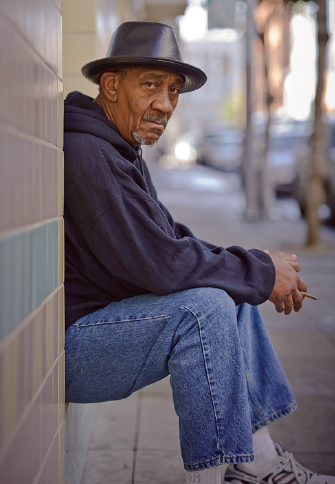

San Francisco, meanwhile, seems a hotbed of senior housing activists and projects. One such program is Planning for Elders’ Senior Survival School, which educates seniors and disabled people on their housing rights. Another program is Seniors Organizing Seniors (SOS), a tiny band of seven formerly homeless men and women who, led by their “executive director,” Bobby Bogan, advocate for more housing and bimonthly distribute hot food to other seniors living under freeways and bridges, in parks and alleyways.

Delbert Scott, now living in San Francisco, is a charter member of this fearless crew. He is out of the shelter and living in a subsidized hotel studio that costs $488 of his monthly $1,200 social security payment. He eats daily hot meals at the nearby Canon Kip Senior Center and via Meals on Wheels. In fact, all seven members of SOS now have roofs over their heads; all have friends and family to care for them. And Delbert is planning a trip to visit his son Kent this winter.

Resources

Canon Kip Senior Center, San Francisco, California: www.ecs-sf.org/programs ■ Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C.: www.pewresearch.org ■ National Alliance to End Homelessness, Washington, D.C.: www.endhomelessness.org ■ “A Quiet Crisis in America,” (June, 2002), Commission on Affordable Housing and Health Facility Needs for Seniors in the 21st Century, Washington, D.C.: www.novoco.com ■ AARP, Washington, D.C.: www.aarp.org ■ Northeast Ohio Coalition for the Homeless, Cleveland, Ohio: www.neoch.org ■ Planning for Elders in the Central City, San Francisco, California: www.planningforelders.org.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Faces of Senior Homelessness: San Francisco

Eli Glasper, 72, lived on the streets of San Francisco in the 1990s following a drug possession conviction. Today, he has a room to live in and works with a small group of formerly homeless men and women helping homeless seniors.

Seniors await lunch at the Canon Kip Senior Center.

Seventy-one-year-old “Bones” searches for his lunch ticket at the Canon Kip Senior Center, which provides a hot meal and the opportunity to talk with friends for homeless and low-income seniors.

Delbert Scott, 75, who went from a successful businessman to homeless, chats with a friend near the Hotel Hartland, where he has lived in a modest room for the last ten years.

Charles Ramsey, 66, waits outside the Canon Kip Senior Center before going in for the daily free lunch program.

Delbert Scott, 75, explains how he went from a successful businessman, husband, and father to homeless with just $78 in his wallet.

The Canon Kip Senor Center is a safe and comfortable gathering place for many elderly homeless individuals in San Francisco. Eighty-seven-year-old Savino Avila awaits lunch and a holiday celebration, including gifts on Christmas Day 2010.

Bobby Bogan, 69, once homeless, now spends his time, including Christmas Eve, helping homeless individuals by advocating for services, distributing food, and sharing his story with others.

Resources

Canon Kip Senior Center, San Francisco, California: www.ecs-sf.org/programs ■ Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C.: www.pewresearch.org ■ National Alliance to End Homelessness, Washington, D.C.: www.endhomelessness.org ■ “A Quiet Crisis in America,” (June, 2002), Commission on Affordable Housing and Health Facility Needs for Seniors in the 21st Century, Washington, D.C.: www.novoco.com ■ AARP, Washington, D.C.: www.aarp.org ■ Northeast Ohio Coalition for the Homeless, Cleveland, Ohio: www.neoch.org ■ Planning for Elders in the Central City, San Francisco, California: www.planningforelders.org.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The Historical Perspective—

Josephine Shaw Lowell and the Founding of the Charity Organization Society

by Ethan G. Sribnick

In the midst of the Great Recession, one organization that has led the efforts to help the poorest New Yorkers is the Community Service Society (CSS). In doing so, CSS is fulfilling the mission of poverty relief it set out for itself since it was created through the 1939 merger of two nineteenth-century charitable organizations. Over time, CSS has reoriented its focus away from simply providing assistance to the poor and towards providing avenues to lift poor families out of poverty. Since the welfare reforms of 1996, explains David R. Jones, CSS president and CEO, the organization has concentrated its attention on workforce issues. “We were looking at the ability of people to move from school or non-work into work, and how do you support primarily low wage workers and improve their standard of living and ultimately give them a career path into [the middle class],” Jones elaborates. “Then the recession hit,” and a lot of these programs have “gone into overdrive.”

The efforts of today’s CSS to help poor families become self-reliant reflect the efforts of one of CSS’s predecessor organizations, the Charity Organization Society (COS), during the economic downturns of the late nineteenth century. In 1873, the collapse of an investment bubble wreaked havoc on the economy, striking New York City, the nation’s financial center, particularly hard. By the winter of 1873–74, 25 percent of New York’s labor force was out of work and those who continued to work faced declining wages. The economy would not recover until 1879; in later years, this period would become known as the “Long Depression.”

This portrait of Josephine Shaw Lowell when she was 37 years old was taken shortly before the founding of COS.

The depression’s social problems—families struggling to pay for rent and food, vagrants wandering the streets—spurred the development of social science, as reformers conducted detailed investigations to generate the most efficient solutions to these dilemmas. One of the leading figures calling for systematic investigations of society and scientific charity was Josephine Shaw Lowell. A descendent of the Boston elite and a Civil War widow—she dressed in black for the remainder of her life—Lowell began her career as a volunteer for the State Charities Aid Society, a private organization advocating modernization of New York’s charitable institutions. In 1876, based on her impressive investigative work, Lowell was appointed by the governor to the State Board of Charities making her the first woman named to an official position in New York’s history.

Lowell’s most important contribution was founding New York City’s Charity Organization Society (COS) in 1882, an effort to provide a coherent structure to the provision of charity in the city. Lowell and the other COS founders recognized that the city’s most destitute needed assistance to survive. Yet, Lowell believed that unrestrained charity contributed to pauperism—dependency on charity—a state that was bad for both the individual and for society. “As long as indiscriminate almsgiving continues,” Lowell wrote, “so long will the streets be full of beggars.” Lowell, however, was optimistic about the future of society. “Vagrancy and homelessness need not be permanent evils,” she wrote, “ … they can be cured and they ought to be cured.” This cure rested in scientifically organized private charity that could effectively oversee charitable assistance in the city. The termination of public cash relief in New York City in 1876 provided Lowell with the opportunity to test her theories of scientific charity through COS.

This photograph portrays the friendly visitors associated with the Junior Sea Breeze Hospital, a hospital for children in Brooklyn, New York.

Scientific charity promised to connect each aid-seeker with the charity best suited to their needs. For this to be effective, COS had to procure an agreement with every one of the city’s charities. The organization quickly accomplished this task; in its fifth year of operation, COS proudly announced they had enlisted “nearly every important and influential relief-giving agency and nearly every self-supporting church in the city.”

At the heart of COS’s method were the friendly visitors. These volunteers, mostly women, served two roles. First, they investigated families seeking aid to ensure they were deserving of assistance and to match them with the most appropriate charity. They evaluated whether applicants were “well conducted and industrious” and “temperate and steady,” as well as the family’s “general moral condition.” Second, the visitors attempted to form a personal bond with the families to provide, in Lowell’s words, the “moral oversight for the soul” needed to lift a family out of poverty.

Over the late nineteenth century, COS created a more sophisticated system of investigation and relief than the city had ever seen. Dividing the city into districts, COS set up an office in each and appointed a committee to oversee the work of the friendly visitors. Lowell herself volunteered on a committee on the Lower East Side. Each week the district committee would meet, review the visitors’ findings, and determine the next step for each family. The visitors’ and committees’ work was thorough, not only were the family and neighbors interviewed, but letters were written to anyone that may have had contact with those in need. The records kept by COS and their contacts across the city created a web of knowledge about poor families. By the mid-1890s, COS had already compiled records on 170,000 cases.

This photograph, taken by reformer Jacob Riis in the late nineteenth century, shows poor children at work in their home.

Based in their belief that excessive charity would lead to pauperism, COS would sometimes use these investigations to cut off assistance. When one woman applied for assistance in 1896 claiming that her husband had fled to England and abandoned her, COS traced her history back to 1882 when she had first appealed for charity. The woman’s long history of requests and her prior refusal to accept work led COS to reject her claim.

In most cases, however, COS hoped to recreate the neighborly charity of small towns that was lost in the anonymity of the city. One woman who appealed to COS had been deserted by her husband and left to care for a 12-year-old girl and an 11-year-old boy. Initially, COS found her work as a domestic, but her “inefficiency” lost her every job. Finally, COS located a “well-to-do sister” and sent the family to live with her, transferring “the burden of the community to her own kith and kin.” A German family with five children in which the father was seriously ill provided another success story for COS. The organization found a place for an infant in a day-nursery, an early form of day care, so the mother could work. Additionally, they found work for the older daughters, aged 15 and 12. “In this way,” COS reported, “the family was made self-supporting, and continue to do well.”

This late nineteenth-century image portrays a mother and her four children living in a tenement in New York City.

The history of COS provides a mixed legacy for those on the front lines of fighting poverty today. Lowell and her colleagues often blamed the poor for economic conditions that were outside of their control. At the same time, they developed structures and methods that still inform today’s social service providers. We should not have “too rosy” a view of Lowell’s work, cautions Jones of CSS, but there are “echoes in terms of our work today.” Lowell’s desire to “get data” and provide a scientific portrait of poverty in the city still drives the research conducted by CSS. Lowell and other early leaders of COS also understood the importance of getting “the message out to the public and policy makers about what should be done.” Jones points out that “they were using the new media of the time,” publishing reports and photographs, “to provide an understanding to the public about what was going on.” Today, concludes Jones, “we use some of the same techniques.”

ICPH’s resident historian, Ethan G. Sribnick, takes an in-depth look at the history of family homelessness, poverty, and the development of social services in New York City in the third in this series of columns.

Resources

Community Service Society of New York, New York City: www.cssny.org ■ Community Service Society Papers, Columbia University, Rare Books and Manuscripts Library ■ Boyer, Paul. Urban Masses and Moral Order in America, 1820–1920. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992. ■ Lowell, Josephine Shaw. Public Relief and Private Charity. New York and London: G. P. Putnam’s sons, 1884. ■ Waugh, Joan. Unsentimental Reformer: The Life of Josephine Shaw Lowell. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Guest Voices—

Ready or Not, Here They Come: A Blueprint for School Readiness that Pays Off for All

by Nancy S. Grasmick

American public schools face some very hard choices. Budgets are tightening. Students are falling behind their international peers in numerous academic categories. It has never been more important for us to be clear about our priorities, and to understand where our resources may be spent most wisely. Our future depends on it. Here in Maryland we have found that there is no better investment than high-quality school readiness. Early childhood education has become more than an isolated public policy concern; it has become an integral part of our vision for public education. We can no longer afford to see public education through a K–12 lens. The skills that children develop before age five are so critical to later success that we must attend to the pre-K years as seriously as we do the high school years. So crucial is this issue that if we took all the money we spend on grade 12 and put it toward school readiness instead, we would be far better off for the trade.

After nearly a decade of evaluation and innovation, the results of our attention to early education have been not just encouraging, but stunning. As we enter our tenth year of focused efforts to make every child ready for school, we believe that what we have accomplished here, from our rural mountains, to our sprawling cities, is achievable in every state of the union. Maryland has long been called “America in miniature,” and we are confident that this can hold true in early childhood education as much as it does in geography.

The first step is a commitment to assessment.

Regular assessment of every child entering school paves the way for confirming the effectiveness of readiness initiatives, and sets the stage for accountability. In 2001, when the Maryland State Department of Education (MSDE) took the important step of assessing all kindergarten students, about 49 percent of children had “full readiness” skills. By 2010, that number had risen by an astounding 29 percentage points, to a total of 78 percent of students found to be fully ready to learn. What is more, these improvements were felt by all sub-groups: boys as well as girls, low-income children, children with disabilities, and English-language learners. Early gains at the kindergarten level have been sustained throughout the elementary school years and beyond.

This is great news for all children, but especially meaningful for kids in groups typically the most at risk for not coming to kindergarten fully ready to learn. These students often come to school destined to a low achievement trajectory, unlikely to keep up with their peers, and doubtful of a chance to achieve appropriate grade levels. In Maryland, these children have closed the achievement gap. For example, low-income children who were enrolled as four-year-olds in pre-kindergarten did just as well as the whole group of children. African-American children and English-language learners have made dramatic strides as well. Our decade of investments in early childhood learning has steadily and increasingly paid off. Our commitment to universal assessment has allowed us to track not just overall progress, but the varied and diverse experience of children in all significant sub-groups. This has allowed us to remain accountable in the task of serving our most vulnerable children.

Assessment has also been important in confirming in practice what neurological science had been teaching us for some time: that strong early learning opportunities lead to later academic success. With important language skills established as early as age two, it has been imperative that we find ways to ensure that all children have the opportunity to succeed in elementary school and beyond. We simply cannot be indifferent to the developmental experience of children in the first five years of life. Too many would struggle needlessly from lack of readiness: both the human and budgetary costs would be too high.

After establishing a means of regular testing, it is necessary to understand the short- and long-term economics of early childhood education investments.

Since both the human and financial cost of non-investment are extremely high, and given the current fiscal situation, parents, legislators, and school boards must be made aware of the numbers. When a low-income child lacks the opportunity to learn important early reading skills in the first grade, her trajectory to meet grade level is diminished eight-fold by the time she finishes fifth grade. When our children arrive at kindergarten without the required skills, the likelihood is high that they will require very expensive in-classroom intervention and supports. Some of them will inevitably have to be held back a year at a cost of nearly $12,000. These are only the immediate financial costs. What we risk down the road is repeating the cycle of poverty: a phenomenon for which we all pay dearly.

Three years ago, the Maryland State Department of Education (MSDE) did a study on the long-term effects of high-quality pre-kindergarten education. The astounding results echoed those found in other studies done nationwide. For each dollar we spend on high-quality pre-kindergarten, Maryland generates five dollars in return by the time those children enter college or a career. An earlier study of ours in 2002 revealed that failure to achieve readiness had resulted in a total cost to the K–12 system of $760 million. Investment in early childhood makes sense in terms of education and economics. Our future prosperity and our current educational budget constraints are both integrally entwined with the fate of our most vulnerable children.

A third component is recognizing the institutional and structural barriers that may hinder skill development in children ages 0–5.

For us that meant rethinking how Maryland delivers and oversees child care services. A key strategy in our efforts to expand the reach of high-quality early education was our decision to become the first state in the nation to house early childhood programs under our department of education rather than under more traditional social services agencies. As expected, there were various bureaucratic and technical challenges involved in this transition, but in the end the effort was well worth it. By 2005, MSDE was able to begin overseeing the delivery of early child care services with an eye toward specific learning milestones and the infrastructure necessary to support them. Careful attention was paid to developing a collaborative relationship between MSDE and Maryland Head Start in everything from the handling of vouchers to the establishment of program standards.

A fourth component of our multi-faceted approach to school readiness is focusing on expanding opportunity to a greater and greater number of our children.

Since 2001, we have instituted full-day kindergarten in all schools, expanded access to pre-kindergarten by 25 percent, and increased by six-fold the number of nationally and state accredited early childhood programs. We should constantly be thinking about how we can ensure full readiness for all students. That means more vouchers, more high-quality public and private early care services in all communities, and outreach to parents and children in groups less likely to take advantage of such services, such as homeless students and English-language learners.

A fifth and indispensible component of a commitment to school readiness is quality.

We were not content with merely expanded access to early education; we also found it essential to assure the quality of teachers, programs, and curricula. The consolidation of early care programs under the MSDE’s Division of Early Childhood Development in 2005 allowed us to focus heavily on accreditation standards. Working collaboratively with early care providers, we introduced a number of guidelines for learning environment, curriculum, instruction, assessment, and instructional leadership. For teachers in these early care programs, we expanded opportunities to become credentialed in early learning. By doing so, we could begin to match our commitment to high-quality early education with teachers ready to provide it.

In addition, it is important to incentivize early care providers becoming partners in achieving school readiness.

As businesses in a competitive marketplace, early childhood programs have responded positively to the opportunity to advertise their achievement of accreditation standards. As we continue to educate parents and families, the purchasers of these early care services, about the crucial importance of school readiness, they are becoming more careful consumers. To this end, we are currently developing a star rating system and a published guide that will aid parents in selecting providers who are succeeding at attracting skilled early education professionals, and establishing high-quality, outcome-based programs. By combining investment in professional development, curriculum standards, and consumer awareness, we have witnessed a six-fold increase over the last decade in the number of programs that have adopted state or national quality standards.

Our experience in Maryland has shown that there is no dollar better spent than on early education. This has become quite clear to all involved: parents, educators, businesses, and taxpayers alike. The challenge remains to achieve full readiness for all of our children, in all of our communities. We must now commit to tenaciously embracing the innovations necessary to achieve high-quality early education, while remembering that our youngest learners are the key to our future.

Nancy S. Grasmick is Maryland State Superintendent of Schools. She is the longest-serving appointed schools chief in the U.S. During her 19-year tenure, Maryland has been consistently ranked among the nation’s top-performing school systems, and her pioneering innova-tions have been adopted across the country. Dr. Grasmick’s articles have been featured in newspapers and education journals nationally.

Editor’s Note: The views expressed in Guest Voices are the opinions of the writers and do not necessarily express the views or intent of UNCENSORED or the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness.

Resource

Maryland State Department of Education www.marylandpublicschools.org or 888.246.0016.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

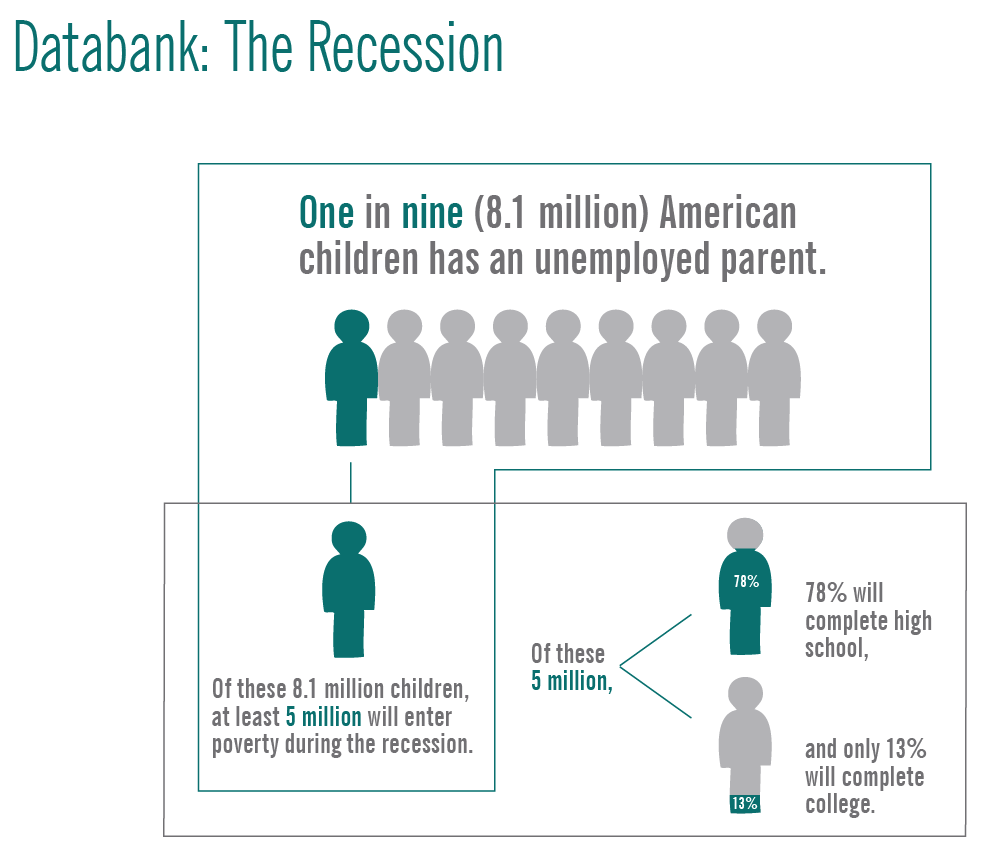

Databank—The Recession

Resource

“Families of the Recession: Unemployed Parents & Their Children,” (January 2010), The Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C.: www.brookings.edu ■ “Simulating the Effect of the ‘Great Recession’ on Poverty,” (September 2009), The Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C.: www.brookings.edu.

Poll Gives Voice to New York City’s Poor

In October 2010, the Community Service Society of New York (CSS) released The Unheard Third 2010, its ninth annual poll of low-income New Yorkers. The poll highlights the issues and obstacles faced by the poor in New York, particularly the one-third of New York City residents of voting age in low-income households. The 2010 survey focused on the issues of jobs and the economy and included 1,414 respondents representing all five boroughs of the city.

Results showed: Struggling to Work: New Yorkers are struggling in the current job market with 30 percent of respondents, and 36 percent of low-income respondents, identifying a lack of jobs or unemployment as the city’s biggest problem.

Unemployed with No Safety Net: Once low-income New Yorkers are unemployed, they have trouble finding new jobs. Two-thirds of low-income residents have been out of work for more than a year and 31 percent have been out of work for three or more years. Additionally, only 28 percent of unemployed respondents have the safety net of unemployment insurance. ■

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

On the Record—

Grassroots Homelessness Advocates

Joan McAllister, Executive Director, Information for Families Inc., New York City

Diane Nilan, Founder and President HEAR US Inc., National

Mark Horvath, Founder, InvisiblePeople.tv, National

The familiar voices of generations-old grassroots advocacy organizations are being reinforced by new voices, all of which relay the urgency of the issues affecting homeless children, youth, and adults. The following are excerpts from conversations with three grassroots leaders who use media to both share the stories of the homeless and to inform and empower the homeless. Each started with a simple idea that grew into a powerful tool for change.

UNCENSORED: How did you get involved with working with the homeless?

McAllister: In 1987, I volunteered with the Citizens Committee for Children of New York. I was with a group assigned to monitor the welfare hotels in midtown New York City, where the city was placing the growing number of homeless families with children. These families lacked badly needed information about resources and services available to them. I brought out the first issue of my newsletter, “HOW…WHEN…WHERE,” that year.

Nilan: I stumbled into this work in the mid-‘80s. I was unemployed, earning money through a variety of odd jobs, when a friend pointed me to a job opening at Joliet (Illinois) Catholic Charities office. It was the time when homelessness was ravaging the Rust Belt and other parts of the country. Since I “only” had one duty, my boss tossed the increasing needs of homeless people at me.

Horvath: Many years ago, I had a great job in the television industry and I ended up homeless on Hollywood Boulevard. So I rebuilt my life back into a three-bedroom house and a 780 credit score. I’ve been not only homeless myself but always in some way doing something for homeless people for the past 14 years.

UNCENSORED: What do you do for the homeless?

McAllister: We publish a free, bilingual newsletter, ten issues a year, 15,500 copies of each, distributed to families in the NYC shelter system and agencies serving them containing information the families need about resources, rights, and services and stories on people and programs to inspire and guide them. We include regularly updated lists of real estate brokers and food pantries. It is primarily aimed at families and particularly those with children.