Publisher’s Note

Dear Reader,

The Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH) welcomes you to the Fall 2011 issue of UNCENSORED magazine. In this publication, we continue to dig deeper into the issues related to family homelessness and poverty—from ensuring academic success for homeless children with out-of-school-time enrichment to the realities of finding and keeping a job that will keep a family out of homelessness. This issue of UNCENSORED spotlights homeless LGBT youth, the not-so-uncommon phenomenon of “couch surfing,” and housing assistance for survivors of domestic violence. Also inside this issue, the history of settlement houses in America is explored, along with theater programs that are used for awareness and advocacy.

For those interested in continuing the conversation on family homelessness, ICPH is holding “Beyond Housing: A National Conversation on Child Homelessness and Poverty” in New York City on January 19–20, 2012. Service providers, practitioners, policy makers, and researchers—along with readers of UNCENSORED—are invited to attend the conference. The keynote speaker is author Jonathan Kozol, a leading scholar on homelessness and education in America. For more information or to register, please visit our conference Web site at www.ICPHusa.org/conference2012.

Thank you to continuing readers, and those new to UNCENSORED, for your interest in the magazine and the important issues it addresses.

Sincerely,

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, Publisher

President and CEO, Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Building Bridges to Learning:

Programs Focused on Reducing Academic Gaps for Homeless Children

by Lee Erica Elder

with Joan Oleck

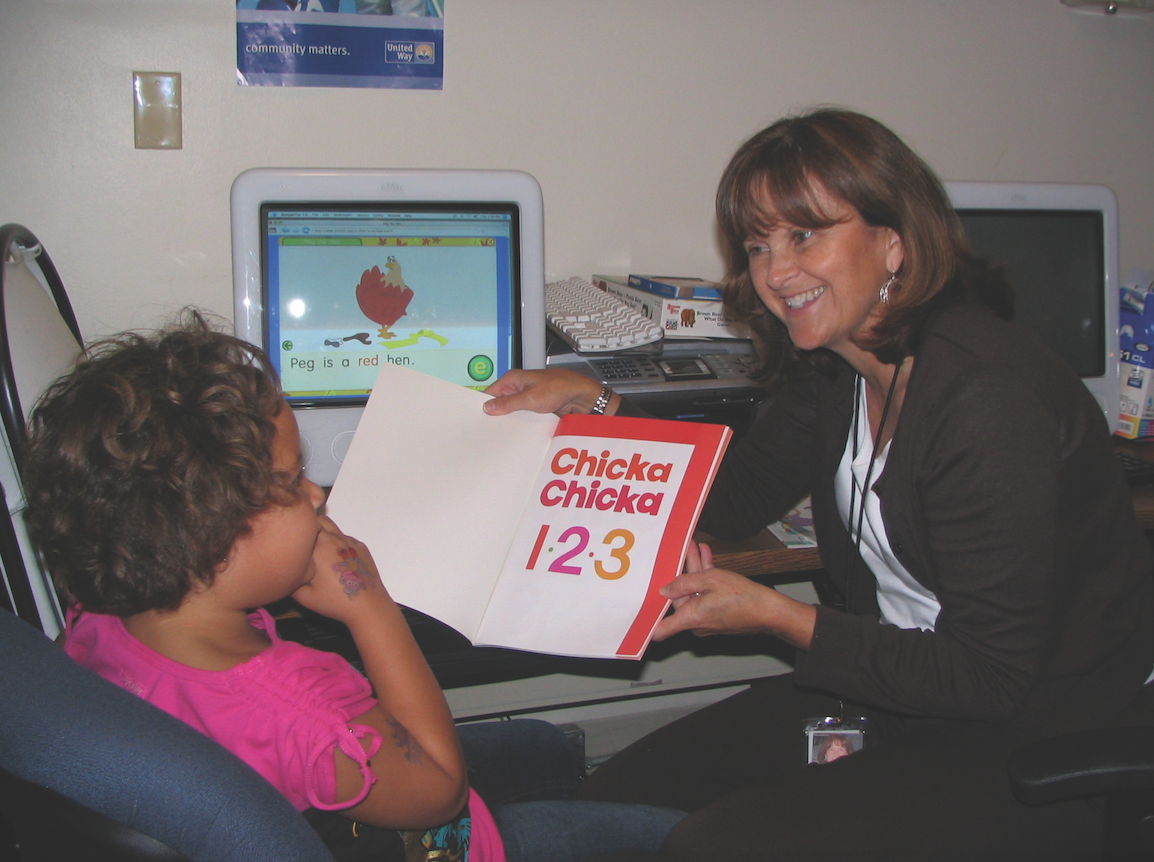

Positive Tomorrows, a private, nonprofit school and after-school program serving homeless and at-risk children in Oklahoma City, believes that homeless children need “all the educational time they can get,” according to president and principal Susan Agel. A student works with an instructor after school to supplement what she is doing during regular school hours.

With schools and educators nationwide confronting an alarming drop in budgets and resources, after-school and out-of-school programs are, increasingly, a primary means for supporting children in unstable living conditions. “Homeless children need all the educational time that they can get,” says Susan Agel, president and principal of Positive Tomorrows, a private, nonprofit school and after-school program serving homeless and at-risk children in Oklahoma City.

“It’s a fallacy to expect that six hours of classroom instruction will work for these children. They need hands-on activities to help internalize the things they learn during the day and constant, supplemental enrichment activities,” Agel says.

Certainly, homelessness creates undeniable barriers to learning that include high mobility, decreased motivation, an inability to meet school enrollment requirements, a lack of transportation, and increased problems of health, hunger, and fatigue.

“Our students are missing layers of learning due to multiple moves, frequent absences and changing schools two or three times in a year,” says Cheryl Opper, founder and executive director of one promising solution in Boston.

That solution is School on Wheels of Massachusetts, or SOWMA, which offers individualized academic services for children in transient living situations. SOWMA is modeled on a School on Wheels in California that Opper had read about; a third such school operates in Indiana.

The notion of turning to an outside facility to address homeless children’s unique education issues makes sense, Opper argues. “It is estimated that each time a child changes schoolsit can take three to six months to recover academically,” she says. “The magic of what we do is one-on-one tutoring and support, treating each student as our only one—giving them what they need, when they need it, and providing stability around a child’s education during a time of chaos and turmoil.”

Why One-on-One Tutoring Is Crucial for Children in Transition

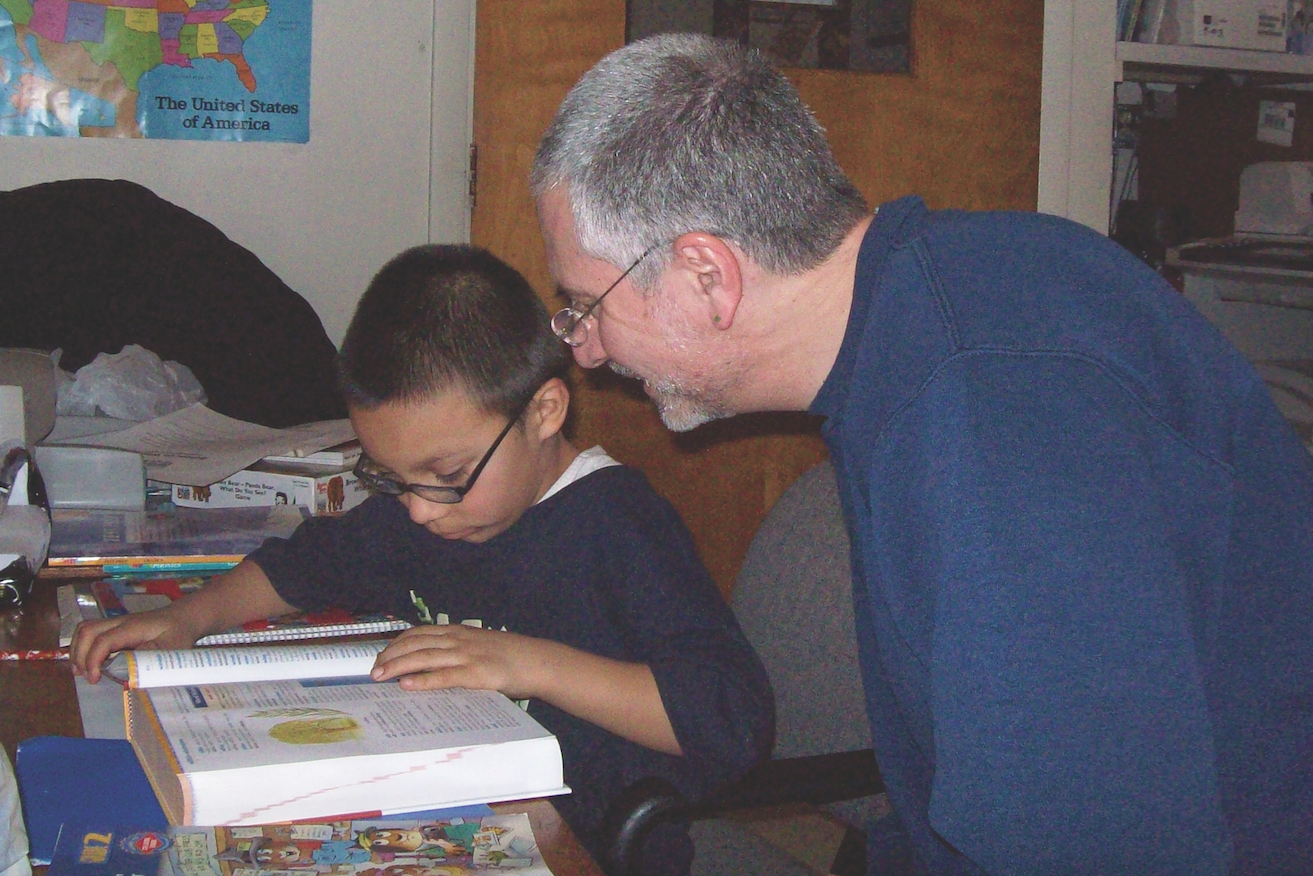

A School on Wheels of Massachusetts staffer encourages a student during one-on-one tutoring. Founder and executive director Cheryl Opper notes that “our students are missing layers of learning due to multiple moves, frequent absences, and changing schools two or three times in a year.

A School on Wheels of Massachusetts staffer encourages a student during one-on-one tutoring. Founder and executive director Cheryl Opper notes that “our students are missing layers of learning due to multiple moves, frequent absences, and changing schools two or three times in a year.

Today, three out of four high school students experiencing homelessness will not graduate, Opper says, citing national statistics. Believing that this bleak scenario could be reversed—that homeless students have the resilience to flourish academically—Opper two years ago started two programs: High School Plus and the South Shore Coalition for Unaccompanied Youth. The results were impressive: Twenty students enrolled in the programs were able to enter college or vocational school following high school. “We have a 94% success rate of students graduating from high school and obtaining higher education,” Opper says proudly.

She cites a student named Darren as a case in point. In 2004, Darren, then in sixth grade, lived in a family shelter in Brockton, a suburb of Boston, and was one of SOWMA’s first recipients of tutoring services. Failing half of his classes, Darren suffered from low self-es

teem, Opper remembers. Then he became involved with SOWMA and its High School Plus program, where he is doing so well that he himself now tutors classmates in math. Currently a senior, Darren hopes to attend Bridgewater State College next year.

Lamar is another School on Wheels success story. A junior at Newbury College in Brookline, Mass., Lamar is now studying culinary arts and hotel management with dreams of becoming a chef and owning his own restaurant. Opper fondly remembers moving Lamar into his first apartment off campus. “We made three trips from his summer dorm room to his new apartment, and he was so proud to show me his new place,” she recalls happily. “I thought back to helping him move out of the single men’s shelter after his high school graduation.”

Pens and Notebooks and Other Barriers to Success

A junior at Newbury College in Brookline, Mass., Lamar is now studying culinary arts and hotel management with dreams of becoming a chef and owning his own restaurant. He shows off his school pride in front of a banner for the college and credits his participation with School on Wheels of Massachusetts for his current success.

Children in transition face multiple academic obstacles, but one of the most basic and easiest to reverse is the lack of school supplies. “Students would rather not turn in a classroom project than tell a teacher they don’t have the school supplies to do it,” Opper points out.

The problem is magnified in areas such as New York City, where previous government funding for programs such as Teacher’s Choice—providing teachers a small amount of discretionary money for classroom and student supplies—has been eliminated. Other locations, however, are devising ways to pay for school supplies: School on Wheels and The Homeless Children’s Education Fund (HCEF) of Pittsburgh both sponsor annual backpack drives, for example.

Receiving supplies from SOWMA helped 12-year-old Sierra McGeoghegan of Brockton, Mass., get her education back on track after attending three different schools and moving six times during the course of just one year. “One night my friend Annie and I were in our motel lobby talking about our school projects, which required some pretty expensive things that our moms could not afford,” Sierra remembers. Then, in what seemed like a feat of serendipitous timing, a visiting School On Wheels tutor asked the girls if they needed any supplies. “It was like a weight was lifted from our shoulders,” Sierra says. “I got an A+ on that project—I went from nothing to having an A+, which really meant a lot to me.”

Further proof that Sierra is doing well today: She recently partnered with her friend Miranda to create a peer newspaper.

Along with gaps in school supplies, an academic challenge homeless students face is their frequent inability to keep up with technology. Katherine Marshall-Polite is a director of youth development for the New York City Department of Education and its Children’s First Network program. She points out that, “Even where students have been provided with laptops and/or desktops to use at school, they often lack accessibility to the Internet once they are back in their residence.” This puts them at a disadvantage to students in stable living situations, who typically have family computer access in their homes and, frequently, their own bedrooms.

Youth impacted by homelessness often count language barriers as another roadblock to academic achievement. “Living in a border city, close to 80% of our identified homeless students are Hispanic, and of those, nearly 50% do not know English,” says Rafael R. Elizondo, homeless liaison for Region 19 in El Paso, Tex.

Elizondo’s program accordingly ensures that all children in homeless situations have the same opportunities as their non-homeless peers, by providing after-school learning that focuses on language skills. The program checks to make sure all partner shelter sites provide a room for student-residents to study and sets up on-site after-school tutoring by certified teachers from the El Paso School Independence District.

Such attention to homeless students pays off: “A homeless student that attended the 2011 Graduation Summit was recognized as having the highest grade-point average (95.5) in her class, and also among the other students from other districts,” Elizondo points out.

Paying attention to the issues homeless students face has a psychological component as well as a resource one. Compassion and discretion are important tools in assisting youth in transition, to help them avoid the negative self-images that can further disrupt learning.

Self-image, of course, is an important part of development for preteens, teens, and in fact students of any age. “I had a ten-year-old come to my office after the first day of school,” remembers Kathryn Cox, administrator at Sara McKnight Transitional Living Center in El Paso. “I asked him how his first day went, and he looked dejected. He said the teacher shared with the class that he was homeless. He was no longer looking forward to his school year.”

To head off such egregious classroom errors, homeless liaison specialists in school districts can guide teachers and administrators in developing sensitivity around homeless students, Cox says. Gaps in service can be identified and the school community can work together to find solutions.

Opper, in Massachusetts, is wary of labeling children as homeless at all. “Our children have a home—it might be a hotel, a family shelter, a car, a campsite, or doubled up with friends and relatives,” she says. “These are their temporary homes until they can have a permanent place to call their own.”

Partnerships between Schools and After-school Programs

Often, combining school-based resources and agencies provides the most comprehensive academic support for children in transition. HCEF in Pittsburgh, for example, provides shelters and transitional housing programs with on-site after-school tutoring, literacy, enrichment, and mentoring.

Recently, HCEF piloted a collaborative program in suburban Clairton, Pa., designed to foster strong connections and align school curricula between the local school district and a homeless provider in the community, Sisters Place.

“We were able to bring the reading specialist from the children’s local school out to the Sisters Place after-school program once a week to work with children individually on literacy for the whole year,” says Laura Bailey, HCEF education program manager. The school guidance counselor and homeless liaison also visited monthly, meeting with parents to discuss important school information and address their concerns. A reading specialist, meanwhile, met with homeroom teachers to gain a sense of the targeted children’s needs, then produce learning plans that after-school center staff could use for planning learning activities.

Says Bailey: “Even though after-school is, and should, differ from day school, for children who are mobile or transitioning out of homelessness, it’s extremely important to build a connection between the two.”

Another partnership exists in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools (CMS) in North Carolina and an outside provider called the After School Enrichment Program (ASEP), which provides after-school and extended-day learning, in addition to individual tutoring with teachers for up to six hours weekly.

Using a curriculum correlated with the NC Standard Course of Study, ASEP site coordinators, school administrators, and teachers work together to ensure that their ASEP programs supplement the learning taking place during the school day, explains Kay Carriera, a district specialist who works with homeless students.

The results, Carriera says, speak for themselves. At West Mecklenburg High School, the graduation rate among homeless students was 79%, higher than the overall school’s graduation rate. “At the end of the 2010–2011 school year, two of our graduating MCV [homeless] students received college scholarships,” Carreira says.

In Minneapolis’ public schools, the focus is on increasing access and participation in the district’s extended-day opportunities for students who are homeless and highly mobile. “All of the district departments and services responsible for these activities were involved in problem solving and identifying strategies to test effectiveness,” says Elizabeth Hinz, district liaison for homeless and highly mobile students. Academic assessment results for [Minneapolis public school] students indicate that students who are HHM average significantly lower results in reading and math scores at all grade levels, Hinz says. “Our belief is that extended-day activities are the best opportunities for them to begin to catch up with their grade-level peers.”

Parents’ Rights and Responsibilities

An instructor at School on Wheels of Massachusetts makes after-school learning fun as she works with a student in the program, reinforcing skills that the student learns during regular school hours so that she keeps pace with her peers.

An instructor at School on Wheels of Massachusetts makes after-school learning fun as she works with a student in the program, reinforcing skills that the student learns during regular school hours so that she keeps pace with her peers.

Of course, along with schools and out-of-school programs, the third part of the triumvirate for advancing homeless students academically is parents themselves. Parents experiencing homelessness frequently are plagued by the misconception that they are not actively involved in their children’s education: A 2009 Duquesne University study of the educational needs of families living in housing for the homeless showed that fully 64% claimed that a lack of knowledge of available educational opportunities was the biggest barrier to their children’s participation in community programming.

“In general neither parents nor agency staff members [in the Duquesne study] claimed to have strong relationships with school teachers or administrators,” says HCEF’s Bailey. “These were parents who cared about their children’s education—79% indicated that they helped their children with homework, and 92% indicated they spoke with homeless agency staff at least once a week about their children’s educational progress.

“One mother even got a job at her children’s school so that she could be near them throughout the day.”

Some school districts have made moves to draw parents into the mix. In Philadelphia, parent ombudsmen are recruited as point people whom parents can see as peers and be comfortable communicating with, says Joe Willard, vice president of policy of the city’s People’s Emergency Center.

In Massachusetts, proud mom Jean McGeoghegan credits her daughter Sierra’s success to effective staff communication. “They listened to me as a parent and listened to her,” McGeoghegan says. “No one ever gave us a hard time. I was really impressed with how strong their educational knowledge was and how they were able to transfer that to my daughter.”

Educators, Bailey says, echoing McGeoghegan, need to see parents not as a hurdle to helping homeless students, but rather a partner in that effort. “That’s a challenge and a goal for this school year,” Bailey says. “To network with the after-school communities around us and find better ways to get that information out to families. We need to do more to help families make informed choices about after-school programming.”

A School on Wheels of Massachusetts after-school student benefits from access to technology during a personalized lesson with a teacher.

Resources

■Positive Tomorrows; www.positivetomorrows.org ■ School on Wheels of Massachusetts; www.schoolonwheelsofmass.org ■ The Homeless Children’s Education Fund; www.homelessfund.org ■ New York City Department of Education, Children’s First Network; schools.nyc.gov ■ Sisters Place, Inc., www.sistersplace.org ■ People’s Emergency Center; www.pec-cares.org ■ Sara McKnight Transitional Living Center, YWCA El Paso Del Norte Region; www.ywca.org ■ El Paso Education Service Center-Region 19; www.esc19.net.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Doubling Up in Down Times:

Lack of Shelters, Overcrowded Shelters, and Lack of Affordable Housing Lead Families to Couch Surf

by Carol Ward

Bradford County, Pa., a rural enclave in northeastern Pennsylvania, has a booming economy these days. The plan to drill and extract gas from the Marcellus Shale reserve has brought prosperity to many in that region of the state. In fact, a study commissioned by the Marcellus Shale Coalition found that the drilling could generate more than 156,000 jobs and $12.8 billion in economic activity in all of Pennsylvania in just 2011 alone.

Communities usually welcome such a boon to their economies, but not all are reveling in the change of fortune. In fact, Dennis Phelps, executive director of Trehab, a community action agency covering six counties in the region, says the recent economic developments have put a nearly unbearable strain on the region’s working poor.

“With all this gas well production there are a lot of workers who have come in, and they’ve basically overrun the market as far as available housing,” says Phelps. “Rents have tripled from $500 to $1,500. The majority of people around here are making $10–15 an hour and it’s hard to pay the rent.”

Many families have been forced out of their homes because they simply cannot afford to live there anymore. “We see it and we can do nothing,” he says. “We have no tools in the tool chest to help these people. They’re on their own. They’re either doubling up with family members or maybe migrating out of here to where there are shelter systems, or in some cases they’re staying in little travel trailers. But they’re doubling up all over the place, in places that are often older and substandard even for one family. It increases the risk for potential problems.”

Northeastern Pennsylvania may be somewhat unique in its economic boom, but it is similar to other areas throughout the country in its rise in families who are “couch surfing” in order to survive. Many communities have not tackled the daunting task of counting the number of people living doubled up, but those that have are reporting significant increases since the economy collapsed between 2007 and 2008.

Anecdotally, towns, cities, and states around the country are reporting higher numbers of families living doubled up, often in precarious situations and in less-than-adequate circumstances, due to economic hardship. Some seek shelter with family and friends before ever considering a community shelter option. In other cases, shelters simply are not available. Rural families often have little or no access to shelters, while in some more urban communities, shelters are full and carry long waiting lists.

While service providers are well aware that these families exist, they struggle to track them. Service providers made several attempts to connect with doubled-up families for this report, but for myriad reasons the attempts failed. Doubled-up families generally do not have interaction with service providers in their areas: They are often wary of being “found out,” and some do not consider themselves homeless or in need of assistance because they have a place to live.

Numbers Are Elusive

The National Alliance to End Homelessness (NAEH) released a report in January 2011 that put a spotlight on the doubling up problem nationwide. The report, “State of Homelessness in America,” found that the doubled-up population increased by 12% to more than 6 million people nationwide from 2008 to 2009.

An earlier report from NAEH, “Economy Bytes: Doubled Up in the United States,” provided additional insight into families specifically. “Approximately 2,135,000 people in just fewer than 800,000 families were doubled up in 2008. This represents an 8.5% increase in the number of people in families over 2005, and a 3.5% increase in the number of family units,” the study said. While the report found that more singles than families doubled up, the numbers of families was rising. In 2005, families made up 42.7% of the doubled-up population, a figure that rose to 44.2% in 2008.

Anecdotally, the numbers have risen further in the past few years due to the deterioration in the economy in 2009 and a lack of broad-based recovery since then. But service providers say counting these precariously housed families is difficult at best.

Eva Barela, a McKinney-Vento grant coordinator covering 13 rural school districts of San Luis Valley in south-central Colorado, says she is attempting to identify those who are doubled up by a housing survey done through the region’s school districts. With one family shelter in the entire valley, which covers roughly 8,000 square miles, most families who are homeless are forced to find shelter on their own, most often with family or friends.

In many cases, Barela says, these families are not interested in being counted. Many are undocumented, she says, and even those that are legal residents are worried about having their children taken away. “The communities here are so small that everybody knows everybody’s business, but they don’t dare say anything,” Barela says.

Shame is also a factor, says Gloria Edwards, executive director of Family Promise of Gallatin Valley, a network of interfaith organizations in Bozeman, Mont., that provides shelter and other services at a rotating roster of churches. “Most people are really embarrassed to admit that they’re homeless, and as long as they’re doubled up they don’t view themselves that way,” Edwards says. “There is still a real stigma attached.” Those communities that have found a way to count the portion of the population that housing or living doubled-up have had some eye-opening results.

For example, in a point-in-time Montana Homeless Survey conducted earlier this year, more than 1,300 people in families in Montana slept at the home of a friend or family member on January 26 of this year, and nearly 800 of those people were staying on an emergency basis, simply because they had nowhere else to turn. It is the first time the statewide survey has broken out those who are “couch surfing” on an emergency basis.

“Considering that in 2011 we had about 800 people in families who were homeless, and now we have roughly that same number of persons who were doubled up, that’s a problem,” notes Robert Buzzas, coordinator of the Montana Continuum of Care Coalition.

Buzzas says that in past surveys, “staying with friends or family” has always been an option for people to select, but this year was the first time the survey distinguished between short-term emergency stays and voluntary, longer-term stays. Longer-term stays tend to involve families who collaborate to live together, often for financial reasons but not as an emergency solution, Buzzas says. Short-term emergency stays involve families that bunk with another to avoid the immediate threat of homelessness.

In Florida, a comprehensive count of homeless people in families conducted by the Homeless Coalition of Hillsborough County, which includes Tampa, showed similarly high numbers.

“We counted over 10,000 [people in families] who were living doubled-up with family and friends because of loss of housing or some kind of economic hardship,” says Rayme Nuckles, CEO of the Homeless Coalition of Hillsborough County. Of those, 23% were children, Nuckles adds. The overall number of homeless in the county jumped from just under 10,000 to nearly 18,000, he says.

Rural vs. Urban Challenges

The doubled-up population in America increased by 12% to more than 6 million people nationwide from 2008 to 2009. The owner of this two-bedroom trailer in rural Illinois has had up to 18 family members staying there at one time.

Montana and Hillsborough County, Fla., represent two disparate data points in a growing problem. The Tampa area has several family shelters, but these days they are not adequate to meet the need. But in Montana and in many rural communities nationwide, families often do not have a shelter option at all.

In the San Luis Valley, for example, Barela says residents have to travel as far as 70 miles to the area’s only shelter. In Montana, the state’s large cities, like Helena and Missoula, do not have emergency family shelters, and the situation is even more dire in the state’s often remote rural communities.

But there are a few options in some parts of Montana. Edwards says the majority of families served by Family Promise of Gallatin Valley have tried the doubled-up route but found it to be untenable.

“We’re kind of like the last resort,” Edwards says, noting the program is usually full although there is seldom a waiting list. “Our families sleep in churches and they have to abide by a lot of rules. Some of their privacy is invaded. Once they’re in the program they realize what a great deal it is. …”

In northeastern Pennsylvania, Trehab’s Phelps says the one shelter does not come close to meeting the need. As with Edwards’ experience in Bozeman, Phelps say families come to Trehab often after exhausting their welcome with family and friends. “Generally what we do in our area is utilize motels,” Phelps says, noting there is no momentum to expand services. “The whole concept of a homeless shelter is foreign around here because it’s a conservative area and there are a lot of NIMBY [‘Not in My Backyard’] issues.”

In more urban areas of the country, shelters are more commonplace, but the weakened economy has resulted in increased demand for limited spaces. “We are pretty much full every day,” says Stacy Cleveland, director of Hope Place, a family shelter run by the Seattle Union Gospel Mission. “A lot of time there are [men’s] shelters that will squeeze single women in, sleep them on a mat on the floor, but most can’t take children into a living situation like that.”

The capacity situation forces Hope Place to turn some families away, but Cleveland is wary of the outcome. Noting that about two-thirds of families at Hope Place come from a doubled-up situation, she has heard enough to worry about sending them back. “Some of the women who come to us would have been better off on the streets than staying with the folks that put them up temporarily,” Cleveland says, noting that a family’s only non-shelter option might be a drug house or an abusive or unsafe situation.

In Boulder, Colorado, the Emergency Family Assistance Association provides food and shelter to families in need. Executive Director Terry Benjamin says in this time of limited resources, shelters have to screen families to assess the truly needy. “Our shelters are always full and we don’t serve all homeless families. We can’t—there are so damn many of them living doubled up,” he says. “We want to help the people who are in the most unstable of those doubled-up situations, who are in crisis and they have used that resource to the max.

“If people come to us without exhausting those personal resources, we ask if there is someone they can stay with,” Benjamin adds. “We don’t hang people up by their thumbs and make them come up with that personal support, but in terms of prioritizing people that’s one of the things we look at.”

Providers in St. Paul, Minn., embark on a similar exercise most nights, according to Margaret Lovejoy, executive director of The Family Place, a day center that provides resources and shelter during the day but cannot accommodate overnight guests. She says her center routinely turns families away, and night shelters are equally taxed. For night placements, “The first question asked is, ‘Can you stay where you are for another night and call us in the morning?’” Lovejoy says.

Outreach Efforts

Many service providers are seeking to more clearly identify the numbers and characteristics of the doubled-up populations in their communities. Then they can work to address immediate needs like food and clothing, although this approach, too, faces obstacles.

“There are services available but the problem is that these families have to get established with case management somehow,” says Cleveland. “To apply for public assistance when you don’t have a statement from a landlord or proof of where you are living can be problematic.” She says that even food banks sometimes have restrictions based on ZIP code, eliminating those who cannot prove their place of residence.

Beyond the immediate need, many communities, such as Hillsborough County, are focusing on housing solutions. Nuckles says coming up with an exact number of those living doubled up this year was the first step. But with the county’s Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-Housing funding ending this year, according to Nuckles, addressing the doubled-up problem will be a challenge.

Tampa has been selected by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) as a priority homeless community, Nuckles says. The group wants to operate programs more efficiently, with a focus on rapidly rehousing individuals and families so they do not take so much time in the system, thus freeing up resources for others. Nuckles hopes that will help address the backlog of homeless people needing assistance.

Exacerbating the problem nationwide is the contracting availability of affordable housing. One study,“America’s Rental Housing: Meeting Challenges, Building on Opportunities,” conducted by the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard

University, outlined the problem. According to the study, “in combination, the shrinking affordable stock, falling incomes, and increased competition from higher-income renters have widened the gap between the number of very low-income renters and the number of affordable, adequate, and available units.” The report went on to note that “in 2003, 16.3 million very low-income renters competed for 12 million affordable and adequate rentals that were not occupied by higher-income households. By 2009, the number of these renters hit 18 million, while the number of affordable, adequate, and available units dipped to 11.6 million, pushing the supply gap to 6.4 million.”

Benjamin sees that firsthand in Boulder, where he says working-class families routinely spend 50–70% of their income on housing. Lower wages due to reduced work hours have placed even the most modest accommodations out of reach, and low vacancy rates have pushed average rents higher in recent years.

Trehab in northeastern Pennsylvania is working to resolve a similar problem. The agency recently received approval for two low-income housing units (one a 40-unit facility for families, the other a 20-unit complex for the elderly) and is working on more, according to Phelps. But new housing options in the area are still at least two years away.

“We’ve got a great job situation here, with unemployment at about 6%, but most jobs aren’t paying enough,” says Phelps. “We’re trying to develop affordable housing but it takes so long. Meantime, where the hell do you live?”

Although family homeless shelters are more prevalent in urban settings than they are in rural ones, the weak economy has resulted in more families applying for shelter. The tenant in this one-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn recently took in her unemployed daughter and the daughter’s family, resulting in 13 people sharing this small home.

Resources

Marcellus Shale Coalition; www.marcelluscoalition.org ■ Trehab; www.trehab.org ■ San Luis Valley Board of Cooperative Education Services; www.slvboces.org ■ Family Promise of Gallatin Valley; www.familypromisegv.org ■ Montana Continuum of Care Coalition ■ Homeless Coalition of Hillsborough County; www.homelessofhc.org ■ Hope Place, Seattle Union Gospel Mission; www.ugm.org ■ Emergency Family Assistance Association; www.efaa.org ■ The Family Place; www.famplace.org ■ Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University; www.jchs.harvard.edu.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Invisible in Plain Sight: LGBT Homeless Youth Finding Long-awaited Support

by Diana Scholl

The lack of funding for all homeless youth is alarming—in 2009 just $118 million in federal dollars went to support and provide housing for this population. And currently no specific money is targeted toward LGBT homeless youth.

When Christopher Thomas’ mother entered a cancer center to be treated for leukemia, she reluctantly sent Thomas to live with his grandfather in Ohio. Though nervous, Thomas, then 18, was looking on the bright side. “It was near Ohio State University. I figured if I lived there for an entire year I could go to OSU for college and pay in-state tuition,” he says.

During a Greyhound bus delay in Cincinnati, Thomas’ cell phone rang. It was his grandfather. “He asked me a bunch of weird questions that were irrelevant. Then he asked if I was gay,” Thomas remembers. “I said ‘Of course.’ I’d been out since I was 10. My mom was fine with it, and it hadn’t been an issue.”

On the phone with his grandfather, Thomas overheard his aunt in the room say, “That’s a sin. We can’t have that here. He deserves to be homeless.” Thomas didn’t know what to do. “All through Cincinnati, I was crying real bad. I felt like my entire life took a sour turn,” he says.

Thomas ended up in California, where he was fortunate to find housing at the L.A. Gay & Lesbian Center, which provides transitional housing for those ages 18 to 24, and specifically targets LGBT youth.

“The Gay & Lesbian Center is like my family now. Any time I need help with anything I have people I can go to,” says Thomas, 19. He is a senior in high school, and wants to attend San Francisco State University next year.

“I used to feel so bitter,” he says. “But I know my education is important, and there is so much I can give to the world. That’s the thing that keeps me sane and gives me hope for the future.”

It is estimated that 1.6 million youth under 18 are homeless or are runaways each year. More than half of these youth experienced violence at home. Many are former foster children, who aged out of the system. And a disproportionate number are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT) young people like Thomas.

In places where homeless youth have been asked their sexual orientation and gender identity, LGBT youth have been found to be overrepresented. The Los Angeles Gay & Lesbian Center found that 40 percent of homeless youth in Hollywood are LGBT, while for San Francisco the figure was 30%, according to Larkin Street Youth Services.

According to the comprehensive 2006 report Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: An epidemic of homelessness by the Gay and Lesbian Taskforce and the National Coalition on Homelessness, LGBT homeless youth are at increased risk of abusing substances, engaging in risky sexual behavior, and suffering from depression and other mental health issues. They are also more likely than their heterosexual peers to be victims of violence.

The lack of funding for all homeless youth is alarming—in 2009 just $118 million in federal dollars went to support and provide housing for this population. And currently no specific money is targeted toward LGBT homeless youth.

Despite the uphill battle, the struggles of LGBT youth like Thomas are gaining wider attention at the national level. And in less concrete ways, the federal government is acknowledging LGBT youth. The United States Interagency Council on Homelessness has acknowledged the problems unique to LGBT youth, and now includes LGBT-specific information in its training and technical assistance for Runaway and Homeless Youth Program grantees. This year, in an attempt to prevent future homelessness, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) started funding a $3 million dollar pilot program to provide support to LGBT youth and their families in the child welfare system.

“There’s a push to give programs the tools they need to be more inclusive,” says Andre Wade, youth program and policy analyst at the National Alliance to End Homelessness. “The federal government is very aware that this population exists.”

Still, LGBT-specific housing is rare, with fewer than 25 LGBT-specific housing options across the country. But that number is expanding. Most recently, singer Cyndi Lauper’s “True Colors Residence” supportive housing opened this September in New York City. Named after Lauper’s 1986 hit song, the residence is the first permanent supportive housing for LGBT youth in New York State, and has drawn increased attention to the plight of LGBT youth. Away from the media spotlight, many shelters and services that work with all homeless teenagers and young adults are also providing additional outreach to LGBT youth.

“It’s exciting that people are really interested and paying attention,” says Jama Shelton, coordinator of research, evaluation, and training at the Ali Forney Center in New York City, which conducts federally funded trainings for providers of services to homeless LGBT youth throughout the country. “Years ago the questions were more ‘Are people born this way?’ or ‘Do you think gay marriage should be legal?’ Now the conversation has moved to where we can say, ‘What matters is the here and now.’”

Suggestions to providers include using respectful language when talking to and about LGBT youth, allowing transgender youth to stay in the shelter where they feel most comfortable regardless of the gender on their birth certificates, and ending harassment by staff and other shelter residents.

Family Ties

Named after singer and activist Cindy Lauper’s 1986 hit song, the True Colors Residence is the first permanent supportive housing for LGBT youth in New York State, and has drawn increased attention to the plight of homeless LGBT youth nationally. It opened in September 2011.

Based on anecdotal evidence, it is believed that LGBT youth come from their hometowns to traditionally LGBT-friendly cities, such as New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Michelle McKeever is one such person.

When McKeever’s stepfather kicked her out of their home in Mobile, Ala., at age 18, McKeever, a transgender woman, spent the night in a shed outside Home Depot. After her grandfather gave her money for bus fare to New York, she bounced around—overstaying her welcome with cousins, and spending the night in a men’s shelter, before finally landing at the Ali Forney Center’s transitional housing for LGBT homeless youth. That move changed her life.

“Ali Forney gave me my backbone,” McKeever, 20, says. “They were there for me when I needed it, thro

ugh the depression and suicidal stage. I met a lot of other people, and a lot more friends than I had in my hometown. They made me feel like it matters that I’m still in this world. Now I am strong, steady, balanced. I’ll get depressed, but I don’t have suicidal attempts. I don’t let death get the upper hand.”

McKeever has recently started talking to her family again, after three years of estrangement. “I’m trying to reconnect and restart with them. Family is forever,” she says. “They are not going to go away.”

Maintaining or rebuilding family ties is one of the most important goals for programs that work with homeless youth.

“What we want ultimately is that when they’re 35 years old, [LGBT youth] can be reasonably assured they have somewhere to go for Thanksgiving,” says Curtis Shepard, director of children, youth, and family services at the L.A. Gay & Lesbian Center.

The L.A. Gay & Lesbian Center has long worked with LGBT young adults 18 years and older, and in April received a $13.3 million, five-year grant from the federal Department of Health and Human Services to provide support to children in the child welfare system.

“They are basically the same population that comes to us when they are 18, just further downstream, more damaged and challenged,” Shepard says.

The first of its kind, this grant is attempting to address the underlying issues LGBT youth face that lead to homelessness. The grant targets both self-identified LGBT youth, and those whose family problems are a result of their perceived sexual orientation or gender identity. For example, an eight-year-old girl who is abused by her parents for wanting to wear boys’ clothes would qualify for intervention.

While this project is still in its research stage, the goal is to provide eligible families with additional counseling and services geared toward parental acceptance of children, in the hope of keeping families together. If that fails, according to Shepard, the next-best solution is for children to live with other family members, or in another permanent, loving home.

“We want to reduce the number of years these youth are languishing in the foster care system, so they don’t show up on our doorstep homeless at the age of 18 or 20,” Shepard says.

Preparing for Independence

When Michelle McKeever’s stepfather kicked her out of their home in Mobile, Ala., at age 18, McKeever, a transgender woman, spent the night in a shed outside Home Depot. After her grandfather gave her money for bus fare to New York, she bounced around— overstaying her welcome with cousins, and spending the night in a men’s shelter, before finally landing at the Ali Forney Center’s transitional housing for LGBT homeless youth. That move changed her life.

Because family reunification is not always possible, shelters and other programs that work with homeless young people attempt to provide emotional support, teach skills necessary for independent living, and offer adult role models.

“Life skills, like learning how to fry an egg, is something you learn from someone,” says Laura Hughes, executive director of the Ruth Ellis Center in Highland Park, Mich., which houses LGBT homeless youth up to age 24. “We try to expand the number of mentors and friends who are not predators. We have to build those networks.”

Ruth Ellis Center specifically brings in LGBT adults who have achieved professional success. When a gay small-business owner addressed the crowd, one of the young people said, “I didn’t know gay people owned businesses.”

“They need both the opportunity and possibility,” Hughes says.

Krystina Edwards, 18, is one of Ruth Ellis Center’s success stories. Her mother was addicted to drugs and kicked Edwards out after a fight. At age 16, Edwards was homeless for two months. “I had to do prostitution to make sure I could have a roof over my head,” says Edwards, a transgender woman.

Local Child Protective Services got involved, and Edwards was referred to the Ruth Ellis Center, where she has lived for two years, and where she also currently works as an administrative assistant. She found the life skills class immeasurably helpful.

“They taught me how to balance my checkbook, how to do my own laundry. They taught me how to communicate with people, and how to dress for a job interview,” she says. “I have more faith in myself. Every day I wake up and come to work. It’s been a helping hand. This has been a life-changing experience.”

Edwards expects to get her GED this month, and wants to become an endocrinologist. She says, “I want to help other transgender women.”

Looking to the Future

Soon the federal government will be providing some more help to groups like the Ruth Ellis Center. In April, HHS announced it will provide the first federal grants to LGBT-specific housing providers. The request for proposals is expected to be released in November.

But even with federal funding, the number of beds specifically for LGBT youth is outstripped by the incredible demand. So advocates are working to ensure all housing and services are welcoming.

“There’s very little LGBT-only housing,” Wade says. “We want to make sure that everything is inclusive.”

Resources

National Gay and Lesbian Taskforce and National Coalition on Homelessness Report; www.thetaskforce.org ■ National Coalition for the Homeless; www.nationalhomeless.org ■ Ali Forney Center; www.aliforneycenter.org ■ United States Interagency Council on Homelessness; www.usich.gov ■ True Color Residence, West End Intergenerational Residence; www.intergenerational.org ■ The Los Angeles Gay & Lesbian Center; laglc.convio.net ■ Larkin Street Youth Services; www.larkinstreetyouth.org ■ Ruth Ellis Center; www.ruthelliscenter.org.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

When a Job Doesn’t Add Up

by Amanda Melillo

Homeless clients from all five New York City boroughs must travel to one job center to process paperwork, meet with job specialists, and meet most employment-related requirements. The line to access services often runs down the block, as shown in this photo, as clients and their children wait patiently to enter the Human Resources Administration job center.

When New York City ended the Advantage rent subsidy program in March 2011, that move marked the first time in decades that the city had no targeted housing subsidy program to assist homeless families moving from temporary shelter to permanent housing. Prior to the city’s 2005 plan to end homelessness in five years, homeless families had been prioritized for programs such as Section 8 vouchers or public housing. The city then ended this practice while experimenting with various iterations of rent subsidy programs.

Today it appears that the city has no plans to initiate any new housing programs targeted at those currently residing in family shelters, but instead plans to help homeless clients help themselves—by moving them into employment.

This new emphasis comes at a time when any employment, especially full-time jobs with adequate pay, is hard to find—particularly for those with little job experience or limited education. While the city’s unemployment rate is lower than the national average, that fact masks how the journey from recession to recovery has been and how it is far from over for those on the lowest rungs of the economic ladder. But even for New Yorkers who manage to secure entry-level jobs for low wages, the question that remains unanswered is whether such progress is truly enough to achieve “self-sufficiency.”

The Grim Economic Realities

While the U.S. unemployment rate remained at a stubborn 9.1% from July to August and the nation had zero net job growth, New York City’s unemployment rate was only slightly lower, at 8.7% in July. For those looking for work, it may take a long time to find a job: Over half of the city’s unemployed have been out of work for more than six months, and nearly a third have been out of work for over a year, according to the Fiscal Policy Institute.

Due to the way the unemployment rate is calculated, that 8.7% does not account for those who gave up the job search and dropped out of the labor force altogether. A more accurate measure may be that of labor underutilization. This measure includes those who are working part-time even though they want full-time jobs, as well as discouraged workers who have given up searching. The Fiscal Policy Institute estimates that the city’s underemployment rate was as high as 15.1% as of March 2011.

These numbers demonstrate a continued pressure on the labor market, as many workers compete for full-time jobs. Economists may have declared the recession to be officially over, but even those who can find jobs providing steady, full-time work may remain unable to make ends meet.

“It’s not just that we have an overabundance of jobs that pay pitiful wages, but that the cost of housing is totally onerous,” says James Parrott, chief economist of the Fiscal Policy Institute. “The cost of living is just so high in New York City.”

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) estimates the fair-market rent for a one-bedroom apartment in New York City to be $1,261, and $1,403 for two bedrooms. HUD classifies someone’s housing as affordable if one year’s rent is no more than one-third of that person’s annual gross income. This means that someone living in New York City has to make $56,120 to comfortably afford a two-bedroom apartment.

In its Out of Reach statistics, the National Low Income Housing Coalition calculates how many renters can afford the fair-market rent across the city by borough. In the Bronx, 75% of residents cannot afford the fair-market rent on a two-bedroom apartment, compared to 68% in Brooklyn and 57% in Queens. In fact, for someone working full-time at minimum wage, affordable rent would have to be only $377 a month to meet HUD’s “affordable” housing test. That’s an impossibility in New York City’s private market. To achieve HUD’s standard for fair-market rent on a two-bedroom apartment, someone working for $7.25 an hour would have to put in 149 hours a week.

A high rent burden, then, is unavoidable for low-income workers, particularly single parents. For someone who works full-time at the minimum wage of $7.25 an hour for 40 hours a week, 52 weeks a year, after-tax take-home pay is only $253.09 per week. At that rate, it would be impossible to cover the rent each month, as a worker would need five weekly paychecks just to pay the rent of $1,261 for a one-bedroom apartment.

Advocates are pushing the City Council to adopt a living wage bill, which would require some employers to pay $10 an hour with benefits, or $11.50 an hour without benefits. The full-time worker’s take-home pay is $346.74 per week at $10 per hour, and $397.69 per week at $11.50 per hour. Even someone making one of the living wage rates would have to collect four paychecks in order just to cover the cost of rent, and with very little money left over for additional expenses.

In a city with expensive rents and a high cost of living, making enough money to cover expenses can be a constant worry for families in poverty. Each year, the Community Service Society conducts its Unheard Third survey of low-income New Yorkers, defined as those making up to 200% of the poverty line. Concerns about employment issues have been a running theme in the most recent surveys.

“We usually think that if you’re working full-time you should at least be able to afford the basic necessities like rent and clothes for your kids.”

— Nancy Rankin, Director of Research Community Service Society

Among low-income New Yorkers, 21% say finding or keeping a job is their top personal concern, compared to about 14% of middle- and high-income New Yorkers. This ranks higher for low-income respondents than other perennial concerns such as crime or education.

Additionally, 36% of low-income New Yorkers reported either losing a job, having tips or wages reduced, or both as primary concerns, compared to 27% of middle-income workers (200–400% of the federal poverty line) and 24% of high-income respondents (over 400% of the poverty line). And because low-income workers have fewer assets, the loss of income hits them that much harder.

Among low-income part-time workers, 79% say they want more hours. And 46% percent of all low-income workers worry that their income will not be sufficient to meet basic expenses, while for single mothers this figure rises to 57%—compared to 21% of those with moderate incomes, and to 9% of high-income workers.

“These are people who are working full-time and yet they have serious hardships of not being able to pay for basic things like back-to-school supplies. Thirty percent had wages, hours, or tips reduced; a quarter had health care decreased; 30% fell behind on their rent,” says Nancy Rankin, director of research at the Community Service Society. “We usually think that if you’re working full-time you should at least be able to afford the basic necessities like rent and clothes for your kids. I think this [Unheard Third survey] is making the case that poverty wages or minimum-wage jobs are not enough to be self-sufficient.” Perhaps nobody knows this better than those who are employed, living in shelter, and are unable to save enough to move out.

Living in Limbo

A guard directs waiting homeless clients into the job center.

A guard directs waiting homeless clients into the job center.

For Vera, 23, losing her job set off a domino effect that eventually landed her in a city family shelter along with her husband and their newborn daughter. She had begun working when she turned 16, holding down a steady series of full-time jobs. After she graduated from high school, she briefly attended a local public college, but had to drop out after a semester in order to work full-time. “When I was in college, it was harder for me because I didn’t have parents. I had to choose between school and work to survive,” she says.

She went to work in the sales division of a cable company after leaving her job as a fitness club membership consultant due to low pay and lack of advancement opportunities. She was fired when she could not meet her sales quota during the height of the recession. “All I knew was, I had no job because I was fired when I didn’t hit my sales quota,” she says. “So I was living through my savings; then I lost my car, and I was having a baby.”

She not only gave up her car, but also her cell phone. This made the job search process all the more difficult. “I did tons of interviews, but I didn’t get hired. I didn’t have a cell phone, so employers couldn’t contact me,” she says.

Eventually, she could no longer pay her rent. She gave up her lease and began couch surfing at friends’ apartments. Because she was pregnant and had exhausted her savings, she went on public assistance for the first time in her life.

She found her current job, working in the retail location of an Internet service provider, after she had been on public assistance a short while. She was starting work at the same time she was going through the intake process to get into shelter, and faced the difficulty of meeting the bureaucratic requirements of the process while holding down a job. Employees at the Prevention Assistance and Temporary Housing Office (PATH), the city’s intake center for homeless families, seemed unsympathetic to the demands of her new job, she says. “I went to PATH and they said, ‘You have to come in for intake.’ I said, ‘That’s my work orientation.’ They just shrugged,” she says.

Now she works full-time at 40 hours a week, making $10 an hour. Even though she makes $440 a week before taxes, it is not enough for her family to move out. Her husband cannot yet legally work in the United States because of immigration restrictions, so she is the sole breadwinner for her family. Her benefits have been substantially reduced because of her earned income, to the point where she only receives $16 a month in food stamps.

“I thought I was going to get out of [the shelter] fast. I’m just in limbo. It’s hard to save the money,” she says.

While the city’s retail industry shed jobs during the height of the recession, it has added back all of the jobs lost and then some. Because of this growth, and the availability of entry-level work for those with little to no job experience, the city’s social services agency, the Human Resources Administration (HRA), pushes public assistance recipients to take jobs in the retail sector. Another area ripe for entry-level workers is the home health aid industry, which has proved to be recession-proof. While the need for home health aids is projected to keep growing, the downside to the job availability is the long hours and low pay.

John, 25, went to work as a home health aide because he liked helping people. “I took care of my grandma when I was young. I tried business management, but I didn’t like it. I decided to go into nursing and never looked back,” he says.

John entered the shelter system in at the beginning of the year with his pregnant girlfriend, and their son. They had been staying with his girlfriend’s mother but her landlord threatened to not renew the lease. They came to shelter when they were out of other options.

When John arrived in shelter, he was working 56 hours over seven days a week for $8.50 an hour, at the job he has held for the past two years. Even as a full-time worker, he found he could not find an affordable apartment.

“When we first came, I was making almost $400 a week. I had a hard time finding an apartment on that, and then my hours went down. It hit us hard, and my girlfriend is pregnant,” he says.

He spends his free time looking for a second job and trying to find an apartment for his growing family. “We just need one bedroom, and it’s $1,200 a month for some of them,” he says.

Daniel, 26, came into shelter in the winter of 2010 with his girlfriend and their daughter. Before entering shelter, Daniel had alternated jobs as a restaurant cook and a mover. He was sent to Back to Work, the city’s main welfare-to-work program for public assistance recipients deemed able to hold a job. In the Back to Work program, job vendors who contract with the city help clients with job-search activities, resume writing, and interview skills, and focus on rapid placement into low-wage jobs.

Daniel got discouraged on job searches with droves of other public-assistance clients. He describes getting sent to shopping centers to apply for retail jobs with 50 other Back to Work clients. “Everybody is looking for the same job, at the same stores, and there are so many people. It’s like you’re keeping me from succeeding,” he says.

When John arrived in shelter, he was working 56 hours over seven days a week for $8.50 an hour, at the job he has held for the past two years. Even as a fulltime worker, he found he could not find an affordable apartment.

Earlier this year, he found a job as a cook at a seafood chain restaurant, making $10 an hour for 35–40 hours a week. “The day I got hired was the happiest day I was in shelter,” he says. “I thought, ‘We are going to get out of here.’”

But the reality is much different. Even though his girlfriend is working full-time at a child care facility, he says it is still difficult to save up. Then he worries about what happens when they move out. “The bills are piling up, you can’t meet your lease agreement, and then you’re out on the streets,” he says.

A Bleak Outlook

Meanwhile, the absence of any housing program is already beginning to take its toll on the city’s family shelter system. By July of this year, the city had placed 6,291 families with children into permanent housing since the beginning of the fiscal year, compared to 8,762 families placed by the same time last year—a drop of more than 2,000 placements.

In the meantime, the average length of shelter stay is beginning to creep up. In June of this year, the average length of stay was 309 days, compared to 252 days in the same month last year. This means that the average family is staying more than a month and a half longer, and far longer than the six-month mark DHS uses to classify long-term stayers.

Homeless clients must now save enough to cover the first month’s rent, a security deposit, and the broker’s fee, which in total can run thousands of dollars. Housing specialists have noted that far fewer clients find apartments, particularly as brokers willing to work with the homeless population are scarce. Clients often see only one option left: have DHS pay for a one-way ticket out of the city.

“You would need to work two jobs, and I can’t. It’s just me and my son,” says Tamara, 24, who is temping at office jobs as she tries to save up to get out of shelter, where she’s staying with her four-year-old. “On $1,000 a month, you can’t pay for rent, for food, for clothes and day care, for babysitters.”

Resources

New York City Department of Homeless Services; www.nyc.gov/dhs ■ Fiscal Policy Institute; www.fiscalpolicy.org ■ The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development; www.hud.gov ■ National Low Income Housing Coalition; www.nlihc.org ■ Community Service Society; www.cssny.org ■ Back to Work program, New York City Human Resources Department; www.nyc.gov.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The Historical Perspective—

Settlement Houses: The Original Community-based Family Resource Centers

by Ethan G. Sribnick Boys in the Lenox Hill Neighborhood Orchestra practice violin. Settlements encouraged cultural enrichment by offering free art, theater, and music programs. Photo courtesy Library of Congress, Bain Collection, Prints and Photographs Division.

Boys in the Lenox Hill Neighborhood Orchestra practice violin. Settlements encouraged cultural enrichment by offering free art, theater, and music programs. Photo courtesy Library of Congress, Bain Collection, Prints and Photographs Division.

In cities throughout the United States places with names like “neighborhood house,” “community center,” and “settlement”—examples include Hull House, Henry Street Settlement, Goddard Riverside Community Center, Elizabeth Peabody House, and Lenox Hill Neighborhood House—are among the most active community-based social service providers serving children, families, and the elderly. These organizations, many of which are more than 100 years old, are settlement houses built by middle-class reformers at the turn of the twentieth century in response to the flood of poor immigrants crowding into the nation’s cities.

Settlement houses were established to serve those in need, but also to reform American society—a mission that continues, in part, today. Nancy Wackstein, the head of United Neighborhood Houses, a coalition of New York City settlement houses, invokes this history to characterize the mission of contemporary settlements. “Being a settlement house means you’re not just a service-delivery organization,” she asserts, “you’re also a social-change organization.”

In 1884, British university students opened the first settlement house, Toynbee Hall, in London’s impoverished East End with the goal of promoting cross-class understanding. By moving into the house, middle-class settlement residents hoped to teach the poor about art, music, and culture, while the working-class residents of the neighborhood would expose the settlement workers to the problems of an urban, industrial society.

This concept was attractive to many Americans who visited Toynbee Hall, and settlements soon began to appear in American cities. Stanton Coit opened Neighborhood Guild, later University Settlement, on New York’s Lower East Side in 1886 after spending three months at Toynbee. In 1889, graduates of the nation’s elite colleges for women opened College Settlement, also on the Lower East Side. In that same year, Ellen Gates Starr and Jane Addams founded Hull House on Chicago’s West Side. In 1893, Lillian Wald laid the foundations for the Henry Street Settlement on the Lower East Side. From these first few organizations, settlement houses quickly multiplied. By 1910, there were more than 400 settlements across the country.

All these settlement houses shared a few defining features. First, they provided a place for middle-class residents to live among the poor, allowing for greater interaction and the possibility of mutual understanding. The belief behind this, as Addams explained, was “that the dependence of classes on each other is reciprocal.” Settlements also provided neighborhood-based services. To better understand residents’ needs, settlement workers undertook thorough social-scientific studies of the neighborhoods in which they lived. Finally, settlement houses shared a common vision of social justice that went beyond simply providing services to residents of their respective neighborhoods. They saw the entire overcrowded urban environment as a cause of the social, sanitary, and economic problems from which many residents suffered. Settlement workers were active, therefore, in campaigns to end child labor, provide meaningful housing reform, and build playgrounds as safe places for children to play. All of these projects and others were part of a mission to create social change that would improve the lives of poor families.

Ideally, settlement programming was highly responsive to the evolving needs of neighborhood residents. In most cases this meant that settlements provided diverse services and events. In the morning, young children arrived for day care and kindergarten programs. During the day, families in need were referred to charitable organizations for relief or medical assistance. In the afternoon, school-age children took part in organized recreation, craft classes, or training in music and the arts. In the evening, neighborhood residents met at the house in various clubs and together developed their own solutions to the community’s problems. Some nights, the settlement staged dances, festivals, or concerts, providing an alternative to other sites of leisure, like the dance hall or the neighborhood saloon.

Both men and women lived and worked in settlement houses, but women thrived in this professional environment. Finding greater opportunities than were available in other fields, women led the movement as heads of the most important settlements across the country. Many were members of the first generation of college-educated women. Having earned their degrees, they wanted to do more than manage a house or do clerical work; they wanted work with a purpose. They also wanted an opportunity to move beyond theories and work directly on the social problems of their day. For some, settlement work became a vocation; most residents, however, only stayed for about three years before moving on to other careers.

Today, Henry Street Settlement offers health-care services, job placement assistance, transitional housing, and youth programs from its headquarters on the Lower East Side. Photo courtesy of Henry Street Settlement.

Settlement houses were fairly radical institutions in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Their mission to provide services and craft reforms based on the needs voiced by the members of the local community put them at odds with an earlier tradition of charity. “We had seen the charitable approach to social problems and found it wanting,” recalled Mary Kingsbury Simkhovitch, the founder of Greenwich House in New York. “If social improvements are to be undertaken by one class on behalf of another, no permanent changes are likely to be effected. The participation of all concerned is necessary for sound improvements.” In a period before significant public assistance for the poor, settlements were often major service providers to poor families in their communities.

The creation of a social safety net state in the 1930s incorporated many of the reforms long advocated by settlement workers, but it also made the work of settlement houses seem less relevant. At the same time, the professionalization of social work provided new training for settlement workers but also restrained some of the reformist zeal of the first generation of settlement volunteers. By the 1960s, public grants provided a new funding stream to support the work of settlement houses. The grants also limited the types of activities a settlement house could undertake.

Over time, the combination of government grants and professionalized social workers made settlement houses similar to other urban social service providers. “The front door has become much more narrowly defined because of government funding,” explains Wackstein. “The guidelines for who you can serve, who you can’t serve—it’s kind of antithetical to the original settlement house notion of welcoming all comers and helping anybody who came in whether they were having a problem with their apartment or their kid or mother.” New sources of public funding also created new private service providers with more specialized missions, Wackstein continues. “The settlement houses were generalists. Now there’s specialization; there’s now a separate agency for domestic violence, and there’s a separate agency for homeless runaway youths.” As settlement houses became providers of social services through government contracts, they lost the political activism that characterized the founders. When you are an “implementer of government social policy” with a multimillion dollar budget and hundreds of employees, asks Stephan Russo, executive director of Goddard Riverside Community House, “how radical can you be?”

In spite of the limitations created by government funding and a crowded social services sector, settlements remain some of the most innovative organizations in urban social policy. “There’s still a real commitment among many [settlement houses] to try to make some systemic change rather than just trying to help fix the people that have been the victims of the system,” emphasizes Wackstein. Just as Addams and other founders hoped, many settlements remain “laboratories of ideas and services,” Russo says. Today, settlement houses need to be “flexible, responsive, and innovative,” Russo continues. The best settlements are “saying, ‘Let’s look at neighborhoods and communities and see what the needs are there.’”

Many settlement houses offered classes designed to develop domestic or professional skills. Here, girls learn to sew at Sprague Settlement in Rhode Island. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

In confronting homelessness, for example, settlements certainly played an innovative role. When homeless individuals began showing up on the streets of Goddard Riverside’s Upper West Side neighborhood in the 1970s, the center created a homeless outreach program that has grown to one of the largest in New York. When family homelessness emerged as problem in the same period, Henry Street Settlement established the Urban Family Center, one of the first transitional housing facilities in the nation, providing private accommodations and services to help return families to permanent housing. From their founding to today, settlement houses have developed fitting responses to local community needs.

When Addams first arrived on the west side of Chicago and Wald first moved to the Lower East Side of New York in the late 1800s, both discovered poor immigrants struggling to survive, families living in crowded and largely unregulated housing, and children working as street peddlers or playing in the streets. Because of the work of these women and other settlement workers across the country, conditions for poor families were greatly improved. Today, a variety of laws, regulations, and social programs help support families and children and keep them safe from the conditions that existed in the early twentieth century. The changing social context has, in some ways, altered the mission of settlement houses. But thanks to a revived interest in community-based social services, settlement houses stand out as longstanding examples of neighborhood-based service providers and catalysts for innovation.

Resources

Davis, Allen Freeman. 1967. Spearheads for Reform; the Social Settlements and the Progressive Movement, 1890–1914. New York: Oxford University Press. ■ Simkhovitch, M. 1938. Neighborhood; My Story of Greenwich House. New York: Norton. ■ Trolander, J. 1987. Professionalism and Social Change: From the Settlement House Movement to Neighborhood Centers 1886 to the Present. New York: Columbia University Press. ■ Wald, L. 1915. The House on Henry Street. New York: Henry Holt, Inc.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Acting Out Reality: Homelessness Takes Center Stage at Theaters throughout the Country

Many theaters put on plays to help the audience escape reality, but some are taking an alternate approach, displaying the harsh facts of homelessness on stage for all to see. Utilizing actors of various ages, backgrounds, and abilities, a few theaters share what makes their plays about homelessness worth seeing.

Act One: Venture Theatre in Billings, Mont.

Six teenagers recite four-minute monologues portraying homeless individuals living on the streets of Billings in A Heart Without: Real Stories of Homelessness. Daniele Reisbig, a former AmeriCorps VISTA volunteer for the Billings Area Resource Network and creator of this production, conducted interviews with area homeless, ages 16 to their late 60s, which were transformed into monologues.

One of the teens portrays a young woman abused for years by an older brother and now struggling with mental illness; another portrays a father who sometimes imagines jumping in front of a train, but then, he says, “I think of my kids.”

Though still in their teens, the actors are able to tackle these difficult issues and take on the complex personas of the homeless individuals they portray, according to Sara Butts, associate artistic director of Venture Theatre. “The actors doing the project are more mature students who have experience with tough material,” she says. What’s more, this is not just another part in a play for the teens. “It is a very big deal to them to tell someone else’s story,” Butts adds. “They never got to meet the individuals they represent on stage but they know some of them have been in the audience.”

The impact this project has had on the actors and homeless participants is substantial, but is not the main goal of the program. A Heart Without aims to educate the Billings community about homelessness and raise support for Project Homeless Connect, a one-day event sponsored by the Billings Area Resource Network, where over 50 service providers and 150 volunteers provide a wide range of supports and referral services to at-risk and currently homeless people.

Act Two: Roseneath Theater Company in Toronto, Canada

It may seem impossible to have an upbeat, funny play about family poverty and homelessness, but Danny, King of the Basement is exactly that. Constantly short of enough money to pay for rent, Danny and his mother are always on the move. Danny uses his imagination and positive outlook to overcome his transient lifestyle.

The touring production of Danny has played in 30 states in the United States and in many of the schools in Ontario, Canada. According to a study by the Elementary Teachers Federation of Ontario, children who see the play are more likely to self-identify as being homeless or poor. “Danny is the hero in the play,” says Natalie Ackers, general manager of Roseneath Theater Company. “It helps identify the students in the school who are living in unstable housing. Students will tell their teachers, ‘I’m like Danny,’ and not be ashamed.”

Danny speaks to adults as well as children, according to Ackers. After seeing the play, “Parents look closer at their children’s friends to see if any of them are homeless. They will put an extra sandwich in their child’s lunch if they suspect one of their child’s classmates needs it.”

Act Three: zAmya Theater Project at St. Stephen’s Human Services in Minneapolis The Venture Theatre in Billings, Mont. shows the many faces of homelessness in this scene from their series of monologues, A Heart Without: Real Stories of Homelessness.

The Venture Theatre in Billings, Mont. shows the many faces of homelessness in this scene from their series of monologues, A Heart Without: Real Stories of Homelessness.

Homeless and non-homeless youth and adults come together at zAmya to create theatrical productions. Originally its own entity, zAmya in 2009 joined forces with St. Stephen’s Human Services, a social service provider offering emergency shelter, street outreach, and employment and family assistance.

During National Hunger and Homeless Awareness Week, just before Thanksgiving, zAmya presents its annual Roadshow, performing seven plays in seven days. The following 52 weeks, zAmya offers its show on a fee-for-service basis. Homeroom was the 2010 Roadshow play, about a fictitious school where the classroom topic is homelessness.

The idea for Homeroom came from a zAmya actor who is also a teacher, explains Angela Headland, community arts and education coordinator at St. Stephen’s Human Services. “She recently asked her students what came to mind when they thought of a homeless person. She got very stereotypical responses,” Headland says. “In our play we discuss stereotypes, but we also provide statistics and true stories that counter those stereotypes.”

zAmya, comprised of ten members, ages 18 to their late 50s, includes people from all walks of life. “Most were homeless at one point in time, some by themselves, others with their families,” says Headland. Professionals interested in acting or passionate about the issue of homelessness are also part of the cast.

To hear zAmya actors tell it, the power of the plays leaves as much of an effect on them as it does on the audience. “I joined zAmya in October 2010, and it was really good for me,” says Courtney Waage, a formerly homeless youth from St. Paul, Minnesota. “Working with zAmya really helped me overcome a lot of fear—fear of getting up in front of a crowd, and speaking and acting in front of a lot of people. I never thought I could do that.”

Resources