Letter from the Executive Director

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,

For the last 12 years, ICPH’s Beyond Housing conference has sparked conversations and convened the community of policymakers, service providers, and others dedicated to supporting the needs of families experiencing homelessness.

When the COVID-19 crisis struck the country in March 2020, that community stepped up in a big way. For many, the pandemic’s toll over the past two years has only strengthened their commitment to finding new and long-lasting solutions for the changing needs of families and communities. At ICPH and our affiliate Homes for the Homeless (HFH), the pandemic has taught us to reimagine the ways we foster community. Due to the nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, we made the difficult decision to forego our regular Beyond Housing conference, which normally draws hundreds of attendees at a major hotel and conference center in New York City.

Instead, this year, we’re bringing you together in a different way—through the launch of our new Beyond Housing magazine, a collection of ideas and solutions around family homelessness. Our team at ICPH is smaller than it used to be, and we’ve tailored our research to more directly address the needs of local families in New York City. Yet, we know that when it comes to family homelessness, local issues are also national issues. Many of the lessons we’ve learned and the solutions we’ve found in NYC can easily be applied to other localities, and vice versa.

In this inaugural issue, you’ll find a Q&A with homeless education liaisons in Los Angeles County and an analysis of the New York City Department of Education’s coordination with shelter-based student services during the COVID-19 pandemic. You’ll read about a partnership in Philadelphia that’s working to foster quality early childcare for children experiencing homelessness and its influence on statewide policy, as well as a NYC shelter-based afterschool Youth Council offering peer leadership opportunities to children and teens.

The Urban Resource Institute, which served as a site visit during the 2020 Beyond Housing conference, will share the latest research on their innovative pet-friendly domestic violence shelter model. You’ll learn how pre-existing housing conditions, like overcrowding and low affordable housing stock, exacerbated the COVID-19 and looming eviction crises in NYC’s immigrant communities, as well as strategies for ensuring that documentation requirements don’t impede a family’s search for housing stability. And Family Promise offers us a glimpse into the work that two of their affiliates are doing to ensure that documentation and identification issues do not keep a family from achieving housing stability, especially for those who are asylum seekers. We’ll also feature some enlightening infographics highlighting data from our research and policy unit’s “Snapshots” on employment, disability benefits, and “new parents” in Homes for the Homeless’ four family shelters in NYC.

Through it all, we’ve seen what community and care can do for families, even—or especially—under the most challenging circumstances. Our communities have consistently stepped up in the face of disaster—including hurricanes, the September 11 attacks, and now, a global pandemic—and each time they’ve emerged with new tools, ideas, and resolve.

I’m deeply proud of this community and the ways in which we’ve supported each other and families experiencing homelessness.

We look forward to hearing your thoughts, comments, and stories, and encourage you to connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, or by email at INFO@ICPHusa.org. You can also visit our website at ICPHusa.org for additional content and more opportunities for collaboration.

Sincerely,

John Greenwood

Executive Director

Homes for the Homeless and the Institute for Children, Poverty & Homelessness

The Data Digest

Data and stats often come up at the Beyond Housing conferences. In “The Data Digest,” we want to share not only data that may shine light on the current state of family homelessness in New York City, but also help providers and others think about how they can approach data collection, analysis, and dissemination in a meaningful way.

All of the data shared in this section is pulled from a series of “Snapshots” that social services provider Homes for the Homeless (HFH) put out over the course of 2021 to take the pulse on programmatic and operational topics from resident employment to needs and demographics of new parents (defined as those with a child under the age of 24 months). The overall goal was for program enhancement and staff development but the data also shed light on key issues that others working with families experiencing homelessness might be interested in hearing more about.

Download the PDF and watch this video for some of the data points that stood out.

How to Connect

Max Rein / Policy Assistant, MRein@HFHnyc.org

Caroline Iosso / Senior Policy Associate, CIosso@HFHnyc.org

To access the full Snapshots, click the links below:

Resident Enrollment in Disability Programs

‘The Rules Change Daily’: Documentation and Homelessness Prevention

By Sadie Keller

Lisa Markushewski, case manager at Greater Portland Family Promise (GPFP) in Portland, Maine, has recently found herself somewhat of a specialist in identification and documentation. This is not a skill she expected to develop while working to keep families housed and stabilized.

Amid applying for housing, acquiring necessary social services, and building community ties, most families in GPFP programs are simultaneously embarking on a long and arduous legal journey. According to GPFP Executive Director Michelle Lamm, most of the families served by the organization are new residents of the United States. Ninety-three percent of families served are seeking asylum, the majority from central African countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola.

To respond, the GPFP team has ventured into the complex lattice of state and federal laws that dictate social services, immigration status, and housing. “You have to go back and read the guidelines,” says Markushewski, “and the rules change daily.”

Watch this video for a deeper look into this topic.

This navigation requires collaboration from an entire community, and thankfully, the GPFP has strong partnerships with legal advocates, including Maine Equal Justice. They refer multiple families to the group each year. Attorney Deb Ibonwa, the organization’s policy and legal advocate, connects families to services, provides legal assistance, and manages high-impact litigation. Ibonwa says GPFP’s team identifies when a family faces a legal challenge, like a loophole eviction, tax fraud, or denied benefits. “I rely on [GPFP’s] advice and insight into the issues families face in our community,” says Ibonwa.

Initiating and winning an asylum claim is contingent on having multiple forms of ID and valid certificates, a significant barrier for some families. Administrative snags and international incongruence add to the stress. For example, a person may struggle to track down a birth certificate and request it from their home country. In the case of married couples, the United States may not recognize a union carried out in another country through a traditional ceremony.

When possible, GPFP gets creative. They have acted as notaries for at least six couples, performed legal marriages onsite, and have helped families obtain state-issued photo IDs. While they leave the legal work to experts, GPFP works with families to prepare their asylum claims, including copying documents needed for the application. Claims can involve more than 250 printed pages, so donors have provided credit at local printing stores to help cover the costs.

Gathering required documentation can take months, which means families may live without access to benefits pending their verification. “Too many families are forced to go without basic needs for their children,” says Lamm.

T.J. Putman is executive director of a Family Promise affiliate on the other side of the country, Family Promise of the Mid-Willamette Valley, in Salem, Oregon. Like GPFP, the organization does not require a family to present documentation to enroll in programming, including emergency shelter. “You shouldn’t need an ID to live somewhere safe,” says Putman.

Before working in homeless services, Putman could understand why someone would live without identification, but he did not know the extent to which a lack of documentation would keep a family on the brink of experiencing homelessness. He has been continuously surprised by the centrality of documentation to his work supporting families, noting, “You need documentation to open a bank account, to drive, to apply for an apartment, and to secure a job.”

When they first approach a Family Promise affiliate, most parents are focused on getting out of an unsafe situation and caring for their children. Understandably, renewing a driver’s license is not top of mind. In Portland, many families contact GPFP after an exhausting and traumatic international journey that may have taken months or years. “At intake, all of the families we serve need serious medical attention. They are deeply concerned about their kids,” reflects Markushewski.

Obtaining documentation can feel tedious and bureaucratic, but it has proven to be a necessary checkmark in case management. It is essential to bringing a family out of homelessness—and can bring a family’s long-term goals a little more within reach. “We can work with some landlords to get a family into an apartment and pay for one or two months of rent,” says Lamm. “But eventually, the family will pay. Parents need to have a job or be in training, kids need to be enrolled in school, and everyone needs good healthcare. Each piece of that puzzle requires different forms of ID.”

Under normal circumstances, documentation poses barriers for those living in poverty, and overwhelmingly burdens families of color. The COVID-19 pandemic has further complicated this situation, increasing the wait time for processing credentials and limiting in-person visits at the responsible state offices. In one timely example, ID or Social Security Number requirements for the coronavirus vaccine have kept some families from receiving a dose in some states.

The past two years brought an unprecedented level of funding to renters and landlords, including $46.5 billion in rental assistance. Yet the dollars have been slow to reach those who desperately need them. Some localities, fearing misuse of funds or fraud, have put in place strict requirements that mean it can take offices weeks to verify an applicant. One of the biggest hurdles in the process is the level of required documentation needed. Hoping that states and local governments can streamline the distribution of the funds, the Treasury Department has modified its guidance. It remains to be seen how effectively these funds will be distributed. Family Promise and other organizations fear the long-term repercussions of the end of the national eviction moratorium for families who were unable to access or use allocated funds to catch up on rent.

As they navigate ever-changing webs of federal, state, and local rules, both Family Promise affiliates see opportunities for policymakers and administrators to better support families. In Portland, LD 718, HP 529, an act introduced in the past legislative session, could help close gaps in healthcare eligibility for asylum seekers. The act is currently being re-considered in the current legislative session, and GPFP is hopeful it will be adopted. According to Lamm, the change would help ameliorate health inequities of low-income Mainers who are immigrants and allow case managers like Markushewski to better advocate for their clients, but it is just one of many more substantial changes needed in Portland’s social safety net.

In Oregon, one existing service needs to be strengthened. The state provides no-cost birth certificates for people experiencing homelessness, a helpful tool for Putman’s team as they update and establish documentation for families. But the process is slow, often taking more than 30 days, and COVID-19 contributed to a domino effect. The backlog stalls a family’s ability to access a hotel for one evening, and in the long-term could keep them from receiving essential services.

Ironically, the wait for the special documentation can close a window of opportunity for a family to find housing. In today’s especially tight real estate market, there are few units that families can afford, and when family-suitable and safe spaces do appear, they go quickly. In rare instances, a landlord or organization will accept an interim card as identification. Often, however, no documentation means no apartment.

They live on opposite coasts and serve disparate communities, but Markushewski, Lamm, and Putman all agree that securing documentation is a necessary step to preventing homelessness and maintaining a family’s independence in the long term. Therefore, they believe it is a natural part of the work of homeless services providers. As they work to educate their communities about family homelessness and housing instability, the Family Promise teams are expanding the definition of homelessness prevention to meet the need in their community.

As Lamm says, “It is all about setting the family up for stability.”

Sadie Keller is a policy and program associate at Family Promise, where she focuses on housing policy research, grant management, and partner engagement. What began as a local initiative in Summit, NJ, has become a national movement that involves 200,000 volunteers and has served more than one million family members since its founding. Currently, Family Promise is working in more than 200 communities in 43 states to prevent family homelessness and ensure that families have a safe place to call home and the resources they need during the COVID-19 pandemic.

How to Connect:

Sadie Keller / skeller@familypromise.org

Michelle Lamm / michelle@gpfamilypromise.org

T.J. Putman / tj@familypromisemwv.org

familypromise.org

gpfamilypromise.org

familypromisemwv.org

Creating a Community of Care: DV Survivors, Homeless Families, and Their Pets

By Danielle Emery

Launched in 2013, the People and Animals Living Safely (PALS) program, an initiative of the Urban Resource Institute (URI), serves domestic violence (DV) survivors with pets. Our shelters are among the less than five percent of DV shelters nationwide to offer co-living, where people are housed along with their companion animals in individual units while healing, helping survivors and their entire families access safety.

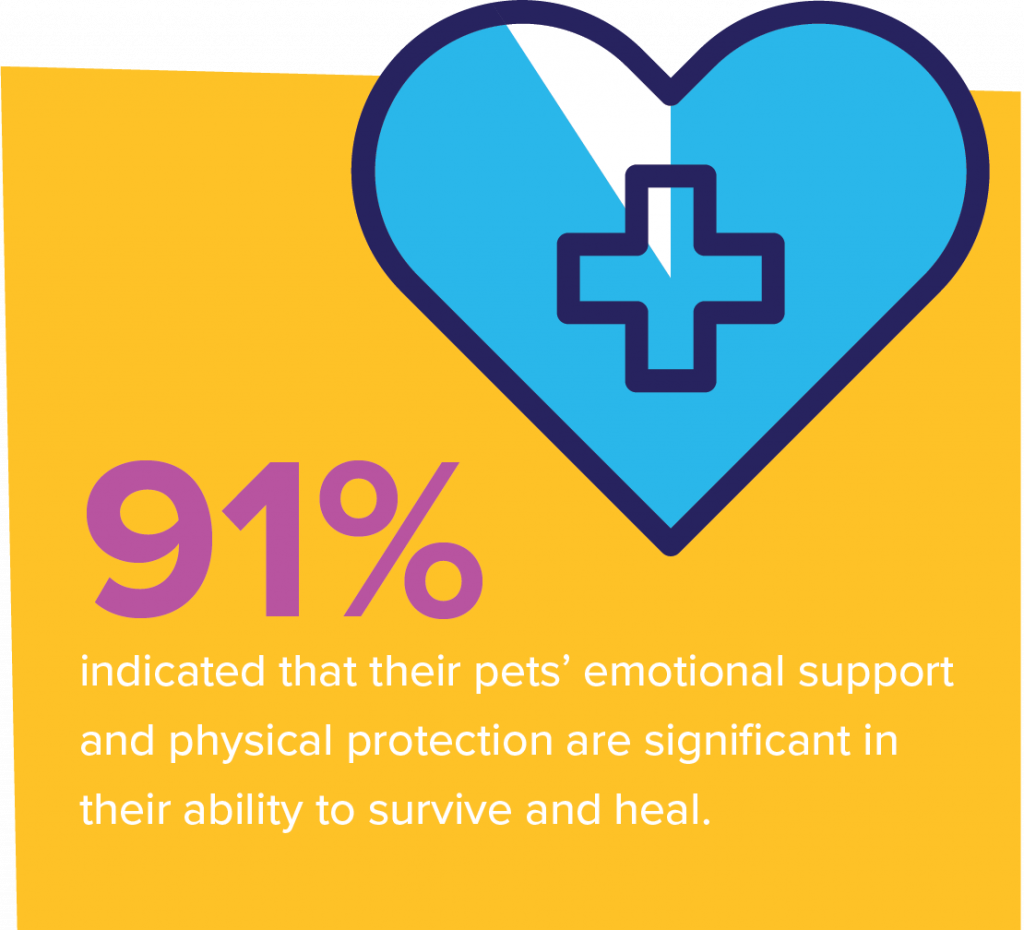

The PALS program operates at the intersection of social services and animal welfare. Research has shown that when there is violence in a home, all members of that home—both people and animals—are at risk and need access to safety. We also understand that pets are an integral part of a family, and especially acknowledge the importance of the human-animal bond for those who have experienced trauma. URI released “The PALS Report and Survey” in May 2021, including the findings of a 2019 survey conducted with the National Domestic Violence Hotline. The survey reinforced the notion that pets are an important part of a survivor’s family, with 91 percent of respondents saying their pet was critical to their own survival and healing, and 97 percent stating that keeping their pet with them was an important factor in seeking shelter. Additionally, concern for a pet’s safety and the lack of family shelters that can accommodate pets are critical reasons why survivors may delay leaving an abusive situation or return to a dangerous environment. Fifty percent of respondents to the PALS survey said they would not seek shelter if they could not take their pets with them. This data corresponds with what experience in the field has consistently shown: pets are essential in survivors’ lives, and the lack of programs that include animals as family members is a significant barrier to accessing safety.

It is also impossible to disentangle domestic violence from family homelessness. Domestic violence shelter systems across the country are intended to provide emergency respite for survivors in crisis. By design, survivors who enter these shelters leave behind their homes and belongings for safety, more often than not becoming homeless in order to flee abuse. New York City’s city-funded domestic violence shelter system is vast, housing 6,400 adults and children each year, but remains woefully inadequate to accommodate every DV survivor seeking safe shelter. A 2019 NYC Comptroller’s report identified domestic violence as the leading cause for homelessness within the NYC homeless family shelter system—over 41 percent of families cited it as the primary reason—a dramatic 44 percent increase over the preceding five years. It is imperative that agencies providing shelter and services to homeless families be aware of and sensitive to the intersection of homelessness and domestic violence, and be equipped to accommodate families with pets in order to help as many survivors as possible.

At the 2020 ICPH Beyond Housing conference, URI hosted a site visit to PALS Place, the first domestic violence shelter of its size built specifically with pets in mind. We talked about our journey to success, from burgeoning idea to impactful and growing initiative, and as a shining example of what is possible with the co-living model. We started as a domestic violence shelter provider dedicated to serving our clients, noticed a gap in those services for clients with pets, and chose to act to fill this need. We are now in a position to share the lessons we’ve learned during this process and are pleased to have this opportunity to provide more information on where we started and updates on how far we’ve come since that 2020 visit, in hopes that it will jumpstart similar initiatives around the country.

Incorporating Pets into Shelter Settings— Addressing Concerns

When URI first launched the PALS program in 2013, we could not have imagined that within eight years we would have successfully welcomed close to 350 families and 450 pets to the program. What began with 10 pet-friendly units in one shelter facility has since grown to nearly 500 units in eight fully pet-friendly shelter buildings across New York City. On any given night, more than 50 families with close to 75 pets reside in URI’s shelters. Although all 500 units are designated as pet-friendly, DV survivors both with and without pets utilize the units on an as-needed basis. This did not happen overnight. As more people learn about the program, we have more families with pets entering our doors. The growth and success of the PALS program has been steady, at a pace matching our organizational capacity, funding, and resources — all important things to consider when taking on this type of initiative.

We started the PALS program without program-specific staff and with no institutional experience welcoming animals in our buildings. This was unfamiliar territory for our agency, and there were many concerns and anxieties from staff and residents: “What about allergies?”, “What happens if an animal becomes aggressive?”, “Will I have to interact with animals?” PALS has fielded these questions internally as the program has expanded to multiple URI shelters. The average social service worker is already busy. The average shelter has few vacancies, with some maintaining waiting lists depending on the locale. So, the new and complicating factors involved in adding people’s pets were an understandable source of worry for both staff and residents. Additionally, most of our staff members did not begin working in social services with the intent of working in close proximity to animals. But we understood that by welcoming pets into shelter, we were able to welcome more humans into shelter. We knew the need for pet-friendly shelter was pressing, and we were determined to build a program that would address these concerns while still providing a critical service to survivors.

In our experience, these anxieties and fears have been unfounded. To date, no staff member or resident has been injured by a pet. Allergies are not a frequent issue. Animals are not running loose or presenting a frequent disturbance to the shelter environment. Providers can avoid potential snags in their pet program by designing a strong initiative and addressing such concerns and needs before animals are ever brought into shelter. The work we did in designing, implementing, and scaling our program as our capacity grew has been key in our success.

The vast majority of PALS pets are dogs, cats, and other small animals. They are pets who have been part of the family for at least a year and are very familiar with bustling city life, interacting with children, and with the noise and congestion that comes with apartment living. Children and adults alike have strong bonds with these animals. Our intake process includes a number of questions designed to determine the pet’s temperament, and we find that dogs, both large and small, are often socialized to be friendly to or ignore strangers. Those that may not have been well socialized due to abuse or other factors are kept under close watch by family members to avoid incidents in shelter.

For those entering shelters due to domestic violence, the process of entering shelter can be a physically and emotionally draining endeavor. We ask a great deal of our clients: they must show up to an unfamiliar location, sometimes giving up or changing a job for their safety. We also ask them to apply for public benefits, so that they can access all available services. While living in a shelter, they must comply with curfews and other rules that may be new to them. In allowing residents to keep a family pet, we are giving them some peace of mind and a stable source of comfort. Retaining their pet means they do not have to separate temporarily or permanently with an important member of their family. It also means that children—and adults—do not have to be further traumatized by separating from their furry friend.

Once new clients with pets are accepted, they must speak with a member of the PALS team to discuss the expectations and responsibilities for having a pet in the shelter setting. Just as clients are expected to meet curfew and other guidelines on site, they must also be responsible for the care of their pet and agree to avoid unnecessary interactions between their pets and other residents. Once clients have acclimated, many staff members at URI say that it’s easy to forget that there are pets residing at their site, since clients take such attentive care of their animals.

We in the PALS program want to share this experience with providers across the country to assure them that while we had fears and anxieties when starting our program, in our nearly 10 years of experience, the benefits have far outweighed any concerns. When handled appropriately, introducing a pet program into your shelter can be another avenue in which you can connect with your clients, reduce trauma, and encourage their positive growth.

Creating a Community of Care

When URI began exploring how to welcome pets into our shelters, we knew that collaboration with other providers—particularly those specializing in animal welfare—would be integral to our program’s success. No single service provider can address every aspect of the complex and unique life experiences of a DV survivor or family experiencing homelessness. Collaboration with animal welfare organizations in your community are paramount to the success of any co-sheltering program. Fortunately, many in animal welfare are ready and willing to work with shelter and social service providers to expand services, keep families together, and prevent pet surrender.

The field of animal welfare has been moving towards a more people-centered approach to helping animals in need, recognizing that caring for animals requires caring for the people who love and care for them. This change has been especially notable over the past two years, as both animal welfare and social services have responded to the COVID-19 crisis. For many Americans, changing employment circumstances and public health measures enacted in response to the pandemic resulted in an extraordinary amount of time spent at home. Animal rescues experienced an unprecedented rate of pet adoptions, and many across the country reported that their pets were a significant factor in managing stress levels during otherwise isolating times.

As a shelter provider, we know this work is complex and demanding, and are not suggesting that agencies immediately begin accepting pets into their facilities. But we are encouraging potential providers consider the issue and begin exploring ways your agency could provide support and resources to people with pets. We and others doing this work across the country are available to provide guidance and direction. URI and PALS can provide training and technical assistance, and resources and training opportunities are also available via the Co-Sheltering Collaborative, Red Rover, SAF-T, Human Animal Support Services, and others.

PALS operates with the belief that all people who have animals in their families deserve access to resources and services in order to remain together, no matter what compounding factors they are experiencing. This includes survivors of domestic violence and both individuals and families experiencing homelessness. But no one is suggesting you do this work totally on your own! Service providers and organizations can and should collaborate across disciplines to contribute to a community of care that addresses all of the needs of individuals and families recovering from domestic violence and experiencing homelessness, including provisions for family pets.

Pushing for Change

There are a number of actions that individuals, agencies, and advocates for policy change can take in advancing resources available to domestic violence survivors and those experiencing homelessness with pets. If you work with clients, collect data on the number of families and individuals you serve that either have pets, or recently relinquished or re-homed pets due to their circumstances. Your local animal shelter may already have some of this data regarding the animals that come into their care—working with them to compile comprehensive data will help you understand the scope of the problem and provide ammunition in advocating for policy change and funding in your community.

There is funding available to providers across the country to support co-sheltering and other programs geared toward helping people and their pets. Originally passed as part of the 2019 Farm Bill, the bipartisan Pet and Women Safety (PAWS) Act is a grant program that provides Congressional funding to enable domestic violence shelters to become pet-friendly and allow survivors and pets to seek safe shelter. In the last two years, the PAWS Act has distributed $4.5 million to providers across the country to support programs for domestic violence survivors with pets. Pet Smart Charities, Red Rover, and other small foundations also have grants available for all types of human services agencies seeking to provide supports to clients with pets.

If pets are present in your or your loved ones’ lives, as they are in nearly 70 percent of American households, consider the joy and comfort they provide and use that experience to advocate for others with pets. There are actions both small and large you can take to help those experiencing homelessness with pets, and there is assistance available no matter what level of action you are looking to take. Reach out to other providers in your community, begin or continue conversations about how to incorporate pets and how that ultimately serves human clients, and most importantly, ask for help! Only by working together can we move towards a shelter system that recognizes the importance of animals in people’s lives and provides supports and resources to keep families together and safe.

Danielle Emery is the People and Animals Living Safely (PALS) director at Urban Resource Institute (URI). For almost a decade, the organization has offered training and technical assistance on the PALS program to all types of providers, including domestic violence and other social services, as well as to animal welfare organizations. URI helps transform the lives of domestic violence survivors and homeless families with a focus on communities of color and other vulnerable populations. URI is the largest provider of domestic violence shelter services in the U.S.

How to Connect:

Danielle Emery / Demery@URInyc.org

URInyc.org

Resources:

Watch this video for a deeper look into the topic:

To learn more about the URI and National Hotline for Domestic Violence report mentioned in the article, download the Executive Summary.

The Saratoga Youth Council: Giving Youth Experiencing Homelessness a Platform for Individual Development and Community Building

By Mary Cummings, Max Rein, and Michael Chapman

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

The issues facing today’s adolescents range from peer pressure and cyberbullying to climate change and a global pandemic. For students experiencing homelessness, factors like housing instability and stigma make an already difficult stage of life even more challenging. Afterschool programs across the nation are working with youth from all backgrounds to empower and support them as they navigate these circumstances.

“Students whose families are experiencing homelessness benefit tremendously from afterschool programs,” says Jodi Grant, Executive Director of the Afterschool Alliance, an organization that works at the national, state, and local levels to ensure that all students have access to quality afterschool programs. “They make learning fun, give students opportunities to explore their interests and engage with peers and adults, and reinforce lessons from the school day. Afterschool programs have been especially important during the pandemic, when so many children are facing isolation, stress, and trauma.”

Saratoga Family Residence, operated by Homes for the Homeless (HFH) and located in Jamaica, Queens, works with the students involved in its afterschool program to help them develop self-esteem, leadership skills, and inner strength—tools necessary to combat negative peer pressure. A critical component of the Saratoga afterschool program is its “Youth Council.” The Saratoga Youth Council aims to give youth a voice, empowering participants under two umbrellas: individual development and community building.

The Council, formed in the summer of 2020, began when Michael Chapman, Director of Afterschool and Recreation at Saratoga Family Residence, noticed young adolescents at the shelter advocating for more program activities tailored to their age group. The Youth Council’s original purpose was to unify the students and give members of the Council, ages nine to 15, a group identity and voice in how activities could be adapted for all ages in the afterschool program, which serves ages five to 15. The Council has since evolved its mission to better understand, develop, and utilize the collective voice of youth.

Staff recruit students for the afterschool program through avenues like referrals from family services, flyers, and a table set up at the entrance to Saratoga with promotional items and information. While the Saratoga afterschool and summer programming follows the NYC Department of Education calendar, students are welcome to join programming at any time. Students are then hand-picked for the Council based on their maturity, proven leadership, and potential to be a positive influence on their peers. The principal goal of Saratoga is to support these children and their parents in their transition into permanent housing. Tomas, who is 13 and a former Youth Council President, and his family have done just that, and he often relays his firsthand experience of moving into permanent housing through video chats with his former fellow Council members and peers.

Youth Council members—there are currently eight—are encouraged to discuss their goals and are then placed on a developmental path to ensure progression toward those goals. This is possible because of a concerted effort across HFH. Chapman constantly relays information about students to staff members, so that they are aware when a donation or opportunity comes up that is pertinent to that student’s needs.

Chrystel, 15, a student at Saratoga, has shown a proclivity for fashion and has been attending a modeling workshop in Manhattan. This was arranged by a staff member connected to the modeling agency who was aware of Chrystel’s interests. For Alenell, 12, who is both skilled in and passionate about music, staff have better equipped her for her artistic endeavors by providing her with a keyboard instrument that was donated to the afterschool program. David, 13, who has proven to be an ardent public speaker, has been mentored by students from St. John’s University, who have helped him hone his presentation skills. David was also part of a group that recently observed the power and social impact of having a collective voice. He and several Youth Council members attended a dinner event sponsored by ABIS (Advancement of Blacks in Sports), an organization founded to “seek equal rights and fair treatment of Black people by examining current institutional policies and practices in an effort to promote racial, social, and economic justice.”

“The ABIS event showed what I could get to in public speaking,” says David. “That I could [speak] in front of 100, 200, or even 300 people.”

Chapman is working with the students to instill in them the sense that with their talents comes a level of responsibility and purpose. Older members of the Youth Council mentor the younger participants, who in turn practice these same leadership skills.

“[In the Youth Council], we discuss how to be a good leader in front of the kids,” says Alenell. “They watch us in everything we do, so they will copy our self-control and respect.”

Youth Council members are increasingly turning their attention to community building, which they practice by assisting in developing new programs and events for the afterschool program.

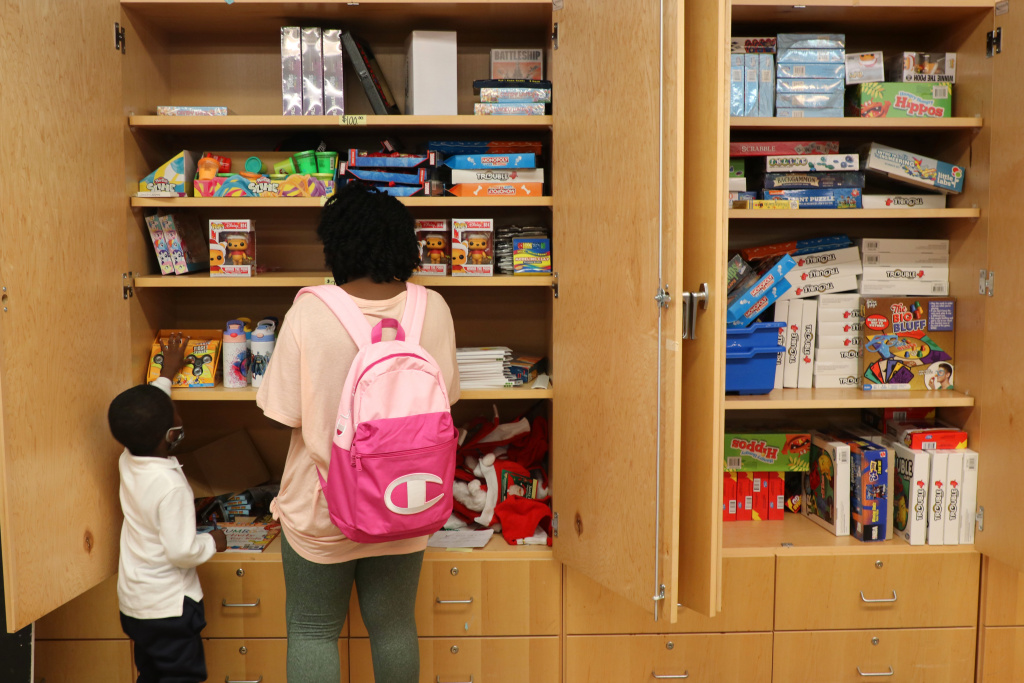

The Saratoga Financial Credit Union was recently created to teach financial literacy and promote leadership, kindness, and integrity. Youth earn “Rec Bucks” by demonstrating positive behaviors such as assisting a classmate, valuing other people’s opinions, and illustrating a willingness to do what is best for everyone. With the earned currency, students can purchase games and toys from the “Rec Bucks” store, managed by Alenell.

According to Chapman, the credit union has also been teaching the students money management and budgeting skills and has been propelling Alenell to new levels of responsibility.

“It teaches Alenell, and those who help manage the store, different things in terms of management,” Chapman explains. “She analyzes the product in the ‘warehouse,’ and when she sees a need for more product, she acts upon it.”

Chrystel describes how new program ideas are born: “When we want to propose something new, first we talk together as youth, and then we talk to Mr. Chapman, and we decide all together.”

One such idea is the Student in Training (SIT) program, which stemmed from one student’s desire to help serve dinner to the students in the afterschool program. As more students volunteered, this blossomed into a two-month initiative where students learn leadership through service. It is an opportunity for them to learn entry-level food management, food delivery, and the elements of creating a positive atmosphere—all centered around serving food.

Since Saratoga’s afterschool program is not constrained by rigid curriculum, this freedom allows for more “skills-based learning,” where children gain valuable life experience through programs such as SIT.

“When students have a voice in shaping the activities their afterschool programs offer, their engagement can deepen as they gain important leadership, organizational, and collaboration skills,” says the Afterschool Alliance’s Grant.

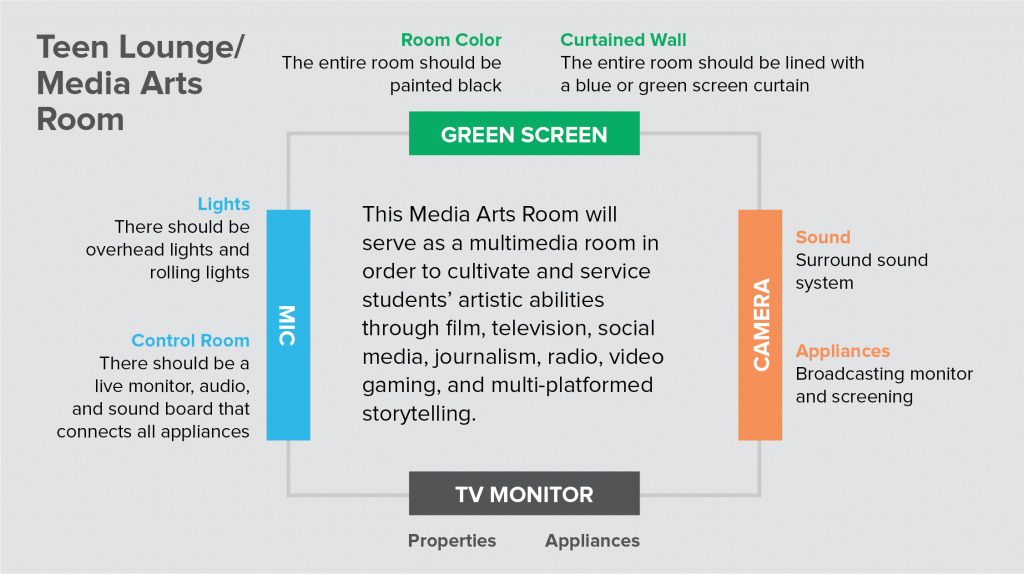

The students in the Youth Council are leaders in conversations about Saratoga afterschool, even when it comes to funding for their new Teen Lounge. They conducted a presentation for longtime HFH collaborator KidCare, outlining their proposal for what the space should be: a place where students can relax and find happiness, whether through the room itself or with each other. They discussed how their dream Teen Lounge would incorporate a bit of everyone’s personal interests in the form of a multimedia room featuring gaming consoles, musical instruments, and arcade games.

KidCare Founder Jonathan Dorfman is looking forward to working with the Youth Council on a regular basis. “The kids showed a great amount of confidence during the presentation,” Dorfman says. “We are so impressed that they take it upon themselves to be leaders for their peers.”

The students focused on operational planning and budgeting for the Teen Lounge project. The numerous life skills they were able to gain—from accountability to compromise—could not have come from a textbook or standard academic experience.

While the Youth Council is currently focused on programming, Chapman is starting to introduce Council members to deeper discussions about public policy. The perfect impetus for these conversations presented itself by way of the NYC mayoral election. Students presented to each other the advice they would offer candidates for New York City Mayor—from more housing to access to youth jobs and space for basketball, and Chapman went so far as to hold a faux press conference, where, acting as mayor, each fielded questions regarding their proposed policies.

Watch the video below to see their responses when asked what actions they would take if elected mayor of New York City.

Discussing public policy has offered students the opportunity to explore the nuances of life in a transitional residence. Thirteen-year-old Youth Council member Joshua has attributed his improved communication skills to living at Saratoga, since it is necessary to communicate with more people in his current community than if he lived elsewhere.

“I feel like this is just something to look back on when I eventually succeed,” says Joshua. “To look back on how I wasn’t in the best situation, but I was able to pull through and succeed.”

It is critical for the afterschool program to be a safe space—providing a place where youth experiencing homelessness can connect with peers who are in similar situations and facing some of the same emotions. This opportunity to share experiences and build relationships outside of school helps students develop communication skills, make friends more easily, become more cooperative, and fight less.1

Moving into the 2021–22 academic year, the Youth Council aims to expand their community building outside of Saratoga. They would ideally like to plan a “Youth Summit” for children at the three HFH family residences in the Bronx and eventually include other shelters for families with children in New York City. They plan to give a tutorial to other youth experiencing homelessness on how they can organize a space to grow individually and collectively in the form of their own Youth Councils.

Hannah Immerman, Senior Programs Associate at HFH, has high hopes for the expansion of the Youth Council to the Bronx HFH family residences.

“The Youth Council centers the youth as leaders and provides a platform for the participants to shape their afterschool program and connect with their peers in meaningful ways,” Immerman says. “Our goal is to replicate this model at our other HFH sites so that more youth can drive the development of their afterschool programs.”

David summed up the benefits of the Youth Council and the importance of representation.

“Overall, it’s good to have a voice as a youth, because most of the time, our community is based off adults’ behavior and how the adults are. It’s good that we can represent ourselves.”

Saratoga Family Residence was featured during the 2020 Beyond Housing conference. Chapman served on the “Putting Children First in Programming” panel alongside Sara Steward of Homefront, Inc. and Jaymes Sime, then of MICHA House, where they discussed the importance of providing access to robust programming for children—birth through college—while temporarily living in shelter. They explored programming options and funding to give kids, and their parents, access to quality pre-K, sports teams, on-site art therapy, and much more.

Mary Cummings is a senior communications associate at Homes for the Homeless. Michael Chapman is director of Afterschool and Recreation at HFH’s Saratoga Family Residence, a 255-unit family shelter in the Jamaica, Queens, neighborhood of NYC. Max Rein is a policy assistant at Homes for the Homeless.

How to Connect:

Mary Cummings / MCummings@HFHnyc.org

Max Rein / MRein@HFHnyc.org

Michael Chapman / MChapman@HFHnyc.org

HFHNYC.org

‘HOUSING IS HEALTH’: Overcrowding, COVID-19, and Evictions in NYC’s Immigrant Neighborhoods

By Sara Herschander

Adelia Farciert was away from home when her sister called around lunchtime: “Did you finish work yet? There’s a fire in the building—they’re evacuating everyone.”

Farciert, 50, who is originally from Puebla, Mexico, rushed home from her job as a housecleaner. The bus skipped her street, by then engulfed in black smoke. It was a chilly day in April 2021, and when Farciert finally got off the bus, she passed by firefighters and fellow tenants, some shivering in pajamas.

“In that moment,” she recalls, “you don’t think of anything at all.”

Farciert and her neighbors had grown closer over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, which had hit families in the two-building, 133-apartment complex hard when cases first exploded in New York City a year prior. The largely immigrant neighborhood had become a hotbed for infection, killing three building residents and leaving many undocumented and mixed-status families, whose members might have differing immigration statuses, without access to government relief. Still, they socialized on the building’s adjacent “Open Street,” on 34th Avenue in Jackson Heights, Queens—part of a citywide initiative launched as a response to the pandemic. The Open Street afforded families, many of whom lived in overcrowded apartments, with more than one person per room to save on rent, a welcome breath of fresh air.

Until crisis struck again. The devastating eight-alarm fire sent residents scrambling out of their six-story, rent-stabilized building. Rent stabilization, which applies to around one million apartments in New York City, prevents landlords from implementing sharp increases on rent and preserves tenants’ right to renew their leases. The NYC Rent Guidelines Board, a nine-member panel appointed by the mayor, determines the level of rent increase permitted in rent-stabilized apartments each year. The fire injured 21 people, displaced more than 200 residents, and scattered a tight-knit community into friends’ and families’ homes or emergency housing in hotels run by the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) throughout the city. By August 2021, over 100 residents, including Farciert and her 11-year-old son, remained housing unstable, fighting month-to-month to remain in city-sponsored hotel rooms, as officials attempted to relocate them to homeless shelters run by HPD. While NYC’s Department of Homeless Services (DHS) provides housing services to New Yorkers experiencing homelessness, HPD is the city agency tasked with preserving affordable housing and providing emergency housing to households displaced by fires and city-issued vacate orders. Yet, as residents have decried, there are no HPD shelters in Queens, which is New York City’s largest borough by area and its second most populous, and finding new affordable housing in their neighborhood has become all but impossible.

“Had people just gone to DHS [NYC Department of Homeless Services] intake, they probably could have ended up at a shelter 10 blocks from home,” says Andrew Solokof Diaz, co-president of the 89th Street Tenants Association, a group that has advocated for residents of the two buildings, which are located at the intersection of 34th Avenue and 89th Street.

In neighborhoods like Jackson Heights, where residents are predominantly foreign-born, community members have been sounding the alarm for years over rising rents, rampant overcrowding, gentrification, and a dwindling stock of affordable housing. When the pandemic arrived, these pre-existing housing conditions led to tragedy, with residents suffering from disproportionate rates of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death. In the economic and housing crisis that has followed, residents have once again found themselves on the brink.

“The rents in those two buildings were some of the lowest in Jackson Heights,” says Solokof Diaz. “This fire was a major shot in the gut to those working to prevent displacement in the area.”

“We either eat or we pay rent,” says Bárbara, a single mother and tenant in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, whose landlord has threatened to kick her and her family out of their apartment, despite national and state eviction moratoriums. A national eviction moratorium declared by Congress was in effect for most tenants from March 2020 to June 2020, after which the Center for Disease Control and Prevention continued to issue its own national moratoriums until the Supreme Court struck them down in August 2021. In New York, tenants have been protected by some form of statewide eviction moratorium since March 2020, with its most recent iteration protecting most tenants until January 2022.

The pandemic, Bárbara says, has forced her and other women to work “more hours for less pay” to afford rent.

Yet, it’s still not enough.

When neighborhoods gentrify, longtime residents often find themselves at a crossroads—unable to match the area’s rising rents, they’re displaced into new neighborhoods or the shelter system. Or, as is often the case for immigrants, who may be reluctant to use city services or leave a community where they speak the language, the only solution may be overcrowding, which allows multiple families to combine incomes to pay rent on just one unit.

After the fire, in the midst of uncertainty, an aunt offered Farciert a space in her home. Yet that aunt had already offered a place to sleep to one of Farciert’s other aunts, one of several members of her extended family also displaced by the fire. “We couldn’t all be there, piled up together,” Farciert reasoned.

Instead, she and her son accepted an offer from HPD for a hotel room near John F. Kennedy Airport. From the hotel, it now takes Farciert two hours to travel to her cleaning clients in Brooklyn. It takes her son over an hour to get to his middle school in Jackson Heights, which had been only four blocks from their old home. The move was meant to be temporary, as the agency attempted to rehouse families, but Farciert was still there in August 2021, four months after she was first displaced.

HPD has offered three options to displaced tenants: affordable housing, defined as costing roughly one-third of a household’s income, in the Bronx or South Queens, or first dibs on a pricey new market-rate apartment complex in Jackson Heights that Solokof Diaz called a “giant gentrifying tower.” According to a meeting in which HPD presented housing options for the displaced tenants, a two-bedroom apartment in the newly constructed Jackson Heights complex would cost $2,849 per month. In contrast, rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Far Rockaway, where one of the affordable complexes is located, would be capped at $1,437 per month.

That means the price of moving back to Jackson Heights is prohibitive for people like Farciert, who’s also found excessive documentation requirements, such as paystubs, bank statements, photo IDs, and other records—which many tenants lost in the fire—to be a barrier to housing in the community.

“If they’re checking your credit score and your status, it’s better to just forget about it,” says Farciert, whose family first moved into the apartment complex 23 years prior, at the height of Jackson Heights’ transformation into a haven for multiethnic immigrant families. “I’m just going to wait to see what my solution here can be,” she says.

She’s not the only one struggling to stay in the neighborhood.

“The communities we serve have been pushed out,” says Annetta Seecharran, Executive director of Chhaya CDC, which offers services to South Asian and Indo-Caribbean immigrant communities in Jackson Heights, and, increasingly, throughout the borough, as residents have left the neighborhood in response to gentrification.

In the Bangladeshi community concentrated in Central Queens, 42 percent of households are overcrowded, compared with 9 percent in the city overall. The neighborhoods of Elmhurst and Corona in Central Queens are the most overcrowded in the city, with 11.3 percent of households severely overcrowded and more than 1.5 people per room, followed closely by Jackson Heights at 10.2 percent. Overcrowding, along with other poor housing conditions, has been a major source of COVID-19 contagion.

“If one member of the household gets infected, because they’re an essential worker, the rest of the household will immediately catch the virus,” says Seecharran, referencing the pandemic’s devastation of overcrowded communities.

According to researchers at Weill Cornell Medical College, severe cases of COVID-19 were 67 percent more likely to occur in overcrowded neighborhoods, with multigenerational households at even greater risk. As of August 2021, in the majority Latino immigrant neighborhood of Corona, Queens, one out of every 183 residents had died of COVID-19. In Manhattan’s majority white and high-income Financial District, only one out of every 3,381 residents had died.

“There were so many traumas, and we all became sick,” recalls Leonila, a mother in Los Sures on the south side of Williamsburg, Brooklyn, a Latino neighborhood greatly impacted by gentrification in recent decades. “It’s been so much for me,” she continues. “I think about how it’s affected my children.”

At a protest and civil action in August 2021, advocates and tenants from throughout the city marched while carrying moving boxes and spray-painted suitcases, meant to symbolize their demands for comprehensive rent relief and eviction prevention for New York City tenants.

“They just keep raising and raising the rent,” says Jorge, a tenant in Woodside, a Queens neighborhood adjacent to Jackson Heights. “We don’t want them to evict us from our homes.”

Overcrowding doesn’t occur in a vacuum and can be considered both a symptom of deeper housing and health crises and a warning sign for evictions, displacement, and, in some cases, homelessness. According to ICPH, more than one-third of families with children who entered the NYC shelter system in 2018 did so because of an eviction or overcrowding.

“Once you’re evicted, you are far more likely to be evicted again,” says Cea Weaver, campaigns coordinator for Housing Justice for All, a statewide advocacy group that organized the anti-eviction rally in August. “You can’t address homelessness without addressing evictions.”

In April 2021, the Association for Neighborhood & Housing Development (ANHD) released a report warning that landlords were filing evictions at rates 3.6 times higher in the zip codes hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, where 68.2 percent of residents are people of color. Despite national and state eviction moratoriums, landlords have still been able to file for eviction with certain limitations and tenant protections, and most housing court cases have been on hold since March 2020. Exceptions to the eviction moratorium have slowly grown since the pandemic began, and for some immigrant tenants, who are more likely to live in informal and unregulated housing or illegal conversions, the protections have never shielded them from eviction. As of press time, the NYS eviction moratorium was set to expire on January 15, 2022.

“It’s a cycle in which harms are perpetuated by other harms,” says Lucy Block, research and policy associate at ANHD. “Where people of color live is where people are dying from COVID-19 and where people are getting evicted.”

Even as COVID-19 cases skyrocketed, rents continued to rise in Central Queens and other gentrifying neighborhoods. In contrast, many of Manhattan’s wealthiest enclaves experienced a significant, if temporary, drop in rent prices, as office buildings closed and residents fled the city. Central Queens, followed by the Northwest Bronx and Sunset Park, is also home to the greatest share of residents employed in the restaurant, hospitality, and retail industries, which experienced the highest rate of layoffs during the pandemic’s early lockdowns.

“At any moment, they can throw us onto the streets,” says María, a tenant and member of Community Action for Safe Apartments in the Bronx. “We have a right to housing until we get our jobs back, and until we have a normal life.”

In September 2021, New York State enacted a new eviction moratorium, built to protect tenants until the beginning of 2022. The announcement came as the state’s rental assistance program—meant to protect tenants regardless of immigration status as the federal moratorium expires—has been off to a slow start. The program provides rental assistance to low and moderate-income households who have experienced financial hardship as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Less than 6 percent of applicants had received payments from the state as of August 2021, and only 15 percent of low-income rental households had applied. Many programs have onerous requirements, including proof of income and residency, that act as a barrier for tenants, even if they are eligible, and if the state fails to distribute rental assistance by a September 30, 2020 deadline, the unspent funds may be returned to the national government.

With many undocumented New Yorkers ineligible for unemployment insurance, stimulus payments, and food assistance, it’s been all but impossible for residents to keep up with living expenses. In August 2021, New York State opened applications for its Excluded Workers Fund to help undocumented workers and others excluded from government relief. Still, Alex Fennell, senior housing organizer for ANHD, says that the resulting patchwork of rent relief and eviction moratoria policies has fallen short of protecting the city’s most vulnerable tenants.

“Every layer of additional documentation and every layer of technical difficulty reduces the number of our most vulnerable tenants who are going to be able to continue with the process,” Fennell says, noting that New York’s rent relief program requires a high degree of digital literacy, including the use of two-factor authentication, which requires users to provide a verification code sent to a trusted device, like a cell phone or laptop, to access their account.

What’s more, advocates like Jennifer Hernandez, lead organizer for Make the Road New York, fear that the city’s looming eviction crisis will make it even harder to fight the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, including new variants: “The only way that we can survive Delta is if we make sure that people are able to stay in their homes,” she asserts.

According to the research group National Equity Atlas, over 800,000 households in New York State are behind on rent. Collectively, they owe over $3 billion in rent debt, and the majority are low-income people of color. As of August 2021, more than 66,000 eviction cases had already been filed in New York since the pandemic began. If adequate eviction prevention measures fail to pass or come to fruition, the results to families’ housing stability could be catastrophic.

“We’ve always paid our rent, but we’re in a pandemic now,” says María. “We’re organizing to be able to live with dignity.”

Sara Herschander is a freelance journalist and editor with a master’s in bilingual journalism from the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY. She reports in English and Spanish on labor, immigration, and housing in New York City.

How to Connect:

Resources:

Watch this video for a deeper look into this topic.

‘LA VIVIENDA ES SALUD’: hacinamiento, COVID-19 y desalojos en los barrios de inmigrantes de Nueva York

Por Sara Herschander

Adelia Farciert se encontraba lejos de su casa cuando su hermana la llamó a la hora del almuerzo: “¿Ya terminaste de trabajar? Hay un incendio en el edificio y están evacuando a todos”, le dijo.

Farciert, de 50 años, quien es originaria de Puebla, México, corrió de inmediato a su casa desde dónde estaba haciendo un trabajo de limpieza.

El autobús que tomó evitóla calle donde estaba ubicada su vivienda, allí solo se veía humo negro. Era un día frío en abril de 2021 y cuando Farciert finalmente se bajó del autobús, se cruzó con bomberos y sus vecinos, algunos temblando en pijama.

“En ese momento no se te ocurre nada en absoluto”, recordó.

Farciert y sus vecinos se habían acercado más durante la pandemia, que afectó drásticamente a las familias en el complejo de dos edificios de 133 apartamentos, cuando los casos de Coronavirus se conocieron por primera vez en la ciudad de Nueva York, hace más de un año.

El barrio, que es en su mayoría habitado por la comunidad inmigrante, se había convertido en un epicentro de infección. Tres residentes de los edificios murieron y muchas familias indocumentadas y de estatus mixto se enfrentaron a distintos retos económicos por no tener acceso a la ayuda del Gobierno.

A pesar de la crisis, los vecinos salían a socializar en la calle que fue cerrada al tráfico y habilitada exclusivamente para los transeúntes y que ubicaba adyacente al edificio en la avenida 34 en Jackson Heights, Queens. Este programa también conocido como calles abiertas hace parte de una iniciativa a nivel ciudadano lanzada como respuesta a la pandemia. El espacio ofrecía a las familias, muchas de las cuales vivían en apartamentos superpoblados, con más de una persona por habitación para ahorrar en alquiler, un agradable soplo de aire fresco.

Cuando se reponían de la pandemia, la crisis los golpeó de nuevo. El devastador incendio de ocho alarmas obligó a a los residentes a salir de su edificio de seis pisos de renta estabilizada.

La estabilización del alquiler, que se aplica a alrededor de un millón de apartamentos en la ciudad de Nueva York, impide a los propietarios implementar aumentos drásticos en el valor de la renta y preserva el derecho de los inquilinos a renovar sus contratos de arrendamiento. La Junta de Reglas de alquiler, un panel de nueve miembros nombrados por el alcalde, determina el nivel de aumento del arriendo permitido en los apartamentos de renta estabilizada cada año.

El fuego dejó heridas a 21 personas, desplazó a más de 200 residentes, y dispersó una comunidad muy unida en casas de amigos, familias, y alojamientos de emergencia en hoteles y albergues familiares patrocinados por el Departamento de Conservación y Desarrollo de la Vivienda (HPD, en inglés). En agosto de 2021, más de 100 residentes, entre ellos Farciert y su hijo de 11 años, seguían teniendo viviendas inestables, luchando mes a mes para permanecer en habitaciones de hotel patrocinadas por HPD, mientras las autoridades intentaban reubicarlos en otras viviendas de emergencia.

El Departamento de Servicios para las Personas sin Hogar (DHS, en inglés) de Nueva York ofrece servicios de vivienda a los neoyorquinos que experimentan la falta de un hogar, y el HPD se encarga de de preservar la vivienda asequible y proporcionar vivienda de emergencia a las familias desplazadas por incendios y órdenes de desalojo de la ciudad. Sin embargo, como los residentes han denunciado, el HPD no les ha ofrecido ninguna otra opción de vivienda de emergencia en Queens, que es el distrito más grande de la ciudad de Nueva York por área y el segundo más poblado. Encontrar nuevas viviendas asequibles en su barrio se ha vuelto casi imposible.

“Si la gente hubiera ido al DHS, probablemente podrían haber terminado en un refugio a 10 cuadras de casa”, dijo Andrew Solokof Díaz, co-presidente de la Asociación de Inquilinos de la Calle 89, que ha abogado por los residentes de los dos edificios, que se encuentran en la intersección de la Avenida 34 y la Avenida 89.

En vecindarios como Jackson Heights, donde los residentes son predominantemente nacidos en el extranjero, durante años los miembros de la comunidad han estado alarmando a las autoridades por el aumento de los alquileres, el hacinamiento, la gentrificación y mejores oportunidades de vivienda asequibler. Cuando llegó la pandemia, estas condiciones de vivienda preexistentes llevaron a la tragedia, con residentes que sufrierom de tasas desproporcionadas de muerte e infección por COVID-19, hospitalizaciónes y muerte. En la crisis económica y de vivienda que ha seguido, los residentes se han vuelto a encontrar al borde del precipicio.

“Los alquileres en esos dos edificios eran de los más bajos de Jackson Heights. Este fuego fue un gran disparo en el intestino a los que trabajan para evitar el desplazamiento en la zona”, dijo Solokof Díaz.

“Comemos o pagamos alquiler”, aseguró Bárbara, madre soltera e inquilina en Sunset Park, Brooklyn, cuyo propietario ha amenazado con echarla a ella y a su familia de su apartamento, a pesar de las moratorias de desalojo nacionales y estatales.

Una moratoria nacional de desalojos declarada por el Congreso estuvo en vigor para la mayoría de los inquilinos desde marzo de 2020 hasta junio de 2020, después de lo cual el Centro para el Control y la Prevención de Enfermedades (CDC, en inglés) continuó emitiendo sus propias moratorias nacionales hasta que la Corte Suprema las anuló en agosto de 2021. En Nueva York, los inquilinos han sido protegidos por una moratoria estatal de desalojos desde marzo de 2020, con su versión más reciente que cobijó a la mayoría de los inquilinos hasta enero de 2022.

La pandemia, dice Bárbara, la ha obligado a ella y a otras mujeres a trabajar “más horas por menos paga” para pagar el alquiler.

Sin embargo, aún no es suficiente.

Cuando los barrios experimentan la gentrificación, los residentes más antiguos a menudo terminan enfrentándose a la encrucijada de igualar los crecientes aumentos de alquileres en el área y los despazamientos. O, como a menudo ocurre con los inmigrantes, que pueden ser reacios a utilizar los servicios de la ciudad o salir de una comunidad donde hablan el idioma, la única solución puede ser el hacinamiento, que permite a varias familias combinar ingresos para pagar el alquiler en una sola unidad.

Después del incendio, en medio de la incertidumbre, una tía le ofreció a Farciert un espacio en su casa. Sin embargo, esa tía ya había ofrecido un lugar para dormir a una de sus hermanas, uno de varios miembros de su familia que también fueron desplazados por el fuego. “No podíamos estar todos allí, amontonados”, afirmó Farciert.

En cambio, ella y su hijo aceptaron una oferta del HPD para una habitación de hotel cerca del aeropuerto John F. Kennedy. Desde el hotel, Farciert ya tarda dos horas en viajar a las casas de sus clientes de limpieza en Brooklyn. Su hijo tarda más de una hora en llegar a su escuela secundaria en Jackson Heights, que había estado a sólo cuatro cuadras de su antiguo hogar. El traslado estaba destinado a ser temporal, mientras que la agencia intentó realojar a las familias, pero Farciert y su hijo aún estaban allí en agosto de 2021, cuatro meses después de que fueron desplazados.

El HPD ha ofrecido tres opciones a los inquilinos desplazados: vivienda asequible, definida como de un costo aproximado a un tercio de los ingresos de un hogar, en el Bronx o el sur de Queens, o ser primeros en la lista de un nuevo complejo de apartamentos a precio de mercado en Jackson Heights, que Solokof Diaz llamó un “torre gigante de gentrificacin”.

para los inquilinos desplazados, un apartamento de dos dormitorios en el complejo recién construido de Jackson Heights costaría $2,849 por mes. En contraste, el alquiler de un apartamento de dos dormitorios en Far Rockaway, donde se encuentra uno de los complejos asequibles, tendría un límite de $1,437 por mes.

Eso significa que el precio de volver a Jackson Heights es excesivo para personas como Farciert, que también ha enfrentado altos precios en recibos de pago, estados de cuenta bancarias, fotografías para documentos de identidad y otros papeles que muchos inquilinos perdieron en el incendio. Esto se convierte en una barrera para la vivienda en la comunidad.

“Si están revisando tu puntaje de crédito y tu estatus, es mejor olvidarlo”, dijo Farciert, cuya familia se mudó por primera vez al complejo de apartamentos 23 años antrás, en el apogeo de la transformación de Jackson Heights en un refugio para familias inmigrantes multiétnicas.

“Voy a esperar a ver cuál puede ser mi solución”, dijo.

No es la única que lucha por quedarse en el barrio.

“Las comunidades a las que servimos han sido expulsadas”, dijo Annetta Seecharran, directora ejecutiva de Chhaya CDC, que ofrece servicios a las comunidades de inmigrantes de Asia del Sur e Indo-Caribe en Jackson Heights, y cada vez más, en todo el distrito, ya que los residentes han dejado el barrio en respuesta a la gentrificación.

En la comunidad banglades í ubicada en Queens, el 42% de los hogares están hacinados, en comparación con el 9% en la ciudad en general. Los barrios de Elmhurst y Corona en Central Queens son los más hacinados de la ciudad con un 11,3% de los hogares en esta condición, con más de 1,5 personas por habitación, seguido de cerca por Jackson Heights con un 10,2%. El hacinamiento, junto con otras malas condiciones de vivienda, ha sido una fuente importante de contagio de COVID-19.

“Si un miembro de la familia se infecta, porque es un trabajador esencial, el resto de la familia se contagia inmediatamente del virus”, dijo Seecharran, haciendo referencia al riesgo en las comunidades hacinadas por la pandemia .

Según investigadores del Weill Cornell Medical College, los casos graves de COVID-19 tenían un 67% más de probabilidades de ocurrir en vecindarios superpoblados, con hogares multigeneracionales en un riesgo aún mayor. A partir de agosto de 2021, en el barrio de inmigrantes de mayor parte latinos de Corona, Queens, uno de cada 183 residentes ha muerto de COVID-19. En el Distrito Financiero, mayoritariamente blanco y de altos ingresos de Manhattan, sólo uno de cada 3.381 residentes murió.

“Hubo tantos traumas, y todos nos enfermamos”, recordó Leonila, una madre en Los Sures en el lado sur de Williamsburg, Brooklyn, un barrio latino desplazado en gran medida por la gentrificación en las últimas décadas. “Ha sido mucho para mí”, continuó. “Pienso en cómo ha afectado a mis hijos.”

En una protesta y acción civil en agosto de 2021, defensores e inquilinos de toda la ciudad marcharon mientras llevaban cajas móviles y maletas pintadas con aerosol, destinadas a simbolizar sus demandas de alivio integral del alquiler y prevención de desalojos para los inquilinos de la ciudad de Nueva York.

“Siguen aumentando y aumentando el alquiler”, dijo Jorge, un inquilino en Woodside, un barrio de Queens adyacente a Jackson Heights. “No queremos que nos desalojen de nuestras casas.”

El hacinamiento no ocurre en el vacío, y puede considerarse un síntoma de crisis más profundas de vivienda y salud, así como una señal de advertencia para los desalojos, el desplazamiento y, en algunos casos, la falta de vivienda. Según ICPH, más de un tercio de las familias con niños entraron al sistema de albergues de Nueva York debido a un desalojo o hacinamiento en 2018.

“Una vez que eres desalojado, es mucho más probable que vuelvas a ser desalojado”, dijo Cea Weaver, coordinadora de campañas de Housing Justice 4 All, un grupo de defensa a nivel estatal que organizó la manifestación contra el desalojo en agosto. “No se puede abordar la falta de vivienda sin abordar los desalojos.”

En abril de 2021, la Association for Neighborhood & Housing Development (ANHD, en inglés) publicó un informe advirtiendo que los propietarios estaban presentando desalojos a tasas 3.6 veces más altas en los códigos postales más afectados por la pandemia COVID-19, donde los residentes son 68.2% personas de color. A pesar de las moratorias de desalojos nacionales y estatales, los propietarios todavía han podido solicitar el desalojo con ciertas limitaciones y protecciones para los inquilinos, y la mayoría de los casos judiciales de vivienda han estado en suspenso desde marzo de 2020. Las excepciones a la moratoria de desalojos han crecido lentamente desde que comenzó la pandemia, y para algunos inquilinos inmigrantes, que son más propensos a habitar viviendas informales y no reguladas o ilegales, las medidas nunca los han protegido del desalojo.

“Es un ciclo en el que los daños son perpetuados por otros daños”, dijo Lucy Block, investigadora y asociada de políticas de ANHD. “Donde vive la gente de color es donde la gente se está muriendo de COVID-19 y está siendo desalojada.”

Incluso cuando los casos de COVID-19 se dispararon, los alquileres siguieron aumentando en Jackson Heights y otros barrios con gentrificación. En contraste, muchos de los enclaves más ricos de Manhattan experimentaron una caída significativa, aunque temporal, en los precios de alquiler, ya que los edificios de oficinas cerraron y los residentes huyeron de la ciudad. El central de Queens, seguido por noroeste del Bronx y Sunset Park, es también el hogar de la mayor parte de los residentes empleados en las industrias de restaurantes, hostelería y comercio minorista, y que experimentaron la tasa más alta de despidos durante los cierres tempranos de la pandemia.

“En cualquier momento, nos pueden echar a la calle”, dijo María, una inquilina y miembro de Acción Comunitaria por Apartamentos Seguros en el Bronx. “Tenemos derecho a la vivienda hasta que recuperemos nuestro trabajo y hasta que tengamos una vida normal.”

En septiembre de 2021, el estado de Nueva York promulgó una nueva moratoria de desalojos, hecha para proteger a los inquilinos hasta principios del próximo año. El anuncio se produjo cuando el programa de asistencia de alquiler del estado, destinado a proteger a los inquilinos independientemente de su estatus migratorio a medida que expira la moratoria federal, ha tenido un comienzo lento. La iniciativa proporciona asistencia de alquiler a familias de ingresos bajos y moderados que han experimentado dificultades financieras como resultado de la pandemia de COVID-19. Menos del 6% de los solicitantes habían recibido pagos del estado hasta agosto de 2021, y sólo el 15% de los hogares de bajos ingresos habían solicitado. Muchos programas tienen requisitos complejos, incluida la prueba de ingresos y residencia, que actúan como una barrera para los inquilinos, incluso si son elegibles. Si el estado no reparte la asistencia de alquiler dentro de un plazo del 30 de septiembre de 2020, los fondos no gastados pueden ser devueltos al Gobierno nacional.

Con muchos neoyorquinos indocumentados no elegibles para el seguro de desempleo, pagos de estímulo y asistencia alimentaria, ha sido casi imposible para los residentes mantenerse al día con sus gastos. En agosto de 2021, el estado de Nueva York abrió solicitudes para un Fondo de Trabajadores Excluidos destinado a ayudar a los trabajadores indocumentados que no eran protegidos por las ayuda del Gobierno. Sin embargo, Alex Fennell, organizador senior de vivienda de ANHD, dice que el mosaico de políticas del alivio de renta y moratorias de desalojo del estado no ha logrado proteger a los inquilinos más vulnerables de la ciudad.

“Cada capa de documentación adicional y cada capa de dificultad técnica reduce el número de nuestros inquilinos más vulnerables que van a poder continuar con el proceso”, dijo Fennell, señalando que el programa de alivio de alquiler de Nueva York requiere un alto grado de alfabetización digital, incluyendo el uso de la autenticación de dos factores. La identificación de dos factores requiere que los usuarios proporcionen un código de verificación enviado a un dispositivo confiable, como un teléfono celular o un computador portátil, para acceder a su cuenta.

Además, defensores como Jennifer Hernández, organizadora principal de Make the Road New York, temen que la inminente crisis de desalojo de la ciudad hará que sea aún más difícil luchar contra la actual crisis de COVID-19, incluyendo nuevas variantes: “La única forma de sobrevivir a Delta es si nos aseguramos de que la gente pueda quedarse en sus casas.”

Según el grupo de investigación National Equity Atlas, más de 800.000 hogares en el estado de Nueva York están atrasados en el alquiler. Colectivamente, deben más de $3 mil millones en deudas de alquiler, y la mayoría son personas de color de bajos ingresos. Hasta agosto de 2021, más de 66.000 casos de desalojo ya se han presentado en Nueva York desde que comenzó la pandemia. Si las medidas adecuadas de prevención de los desalojos no se adoptan o se materializan, los resultados para la estabilidad de la vivienda de las familias podrían ser catastróficos.

“Siempre hemos pagado el alquiler, pero ahora estamos en una pandemia”, dijo María, miembro de Acción Comunitaria por Apartamentos Seguros. “Nos estamos organizando para poder vivir con dignidad.”

Sara Herschander es periodista independiente y editora con una maestría en periodismo bilingüe de la Escuela de Periodismo Craig Newmark de CUNY. Ella informa en inglés y español sobre trabajo, inmigración y vivienda en la ciudad de Nueva York.

Cómo conectarse:

TIME TO BUILD A BETTER SHELTER-TO-SCHOOL BRIDGE: A Retrospective on the Experiences of NYC Students and Families in Shelter during the Pandemic School Year

By Robyn Schwartz with additional reporting by Linda Bazerjian

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

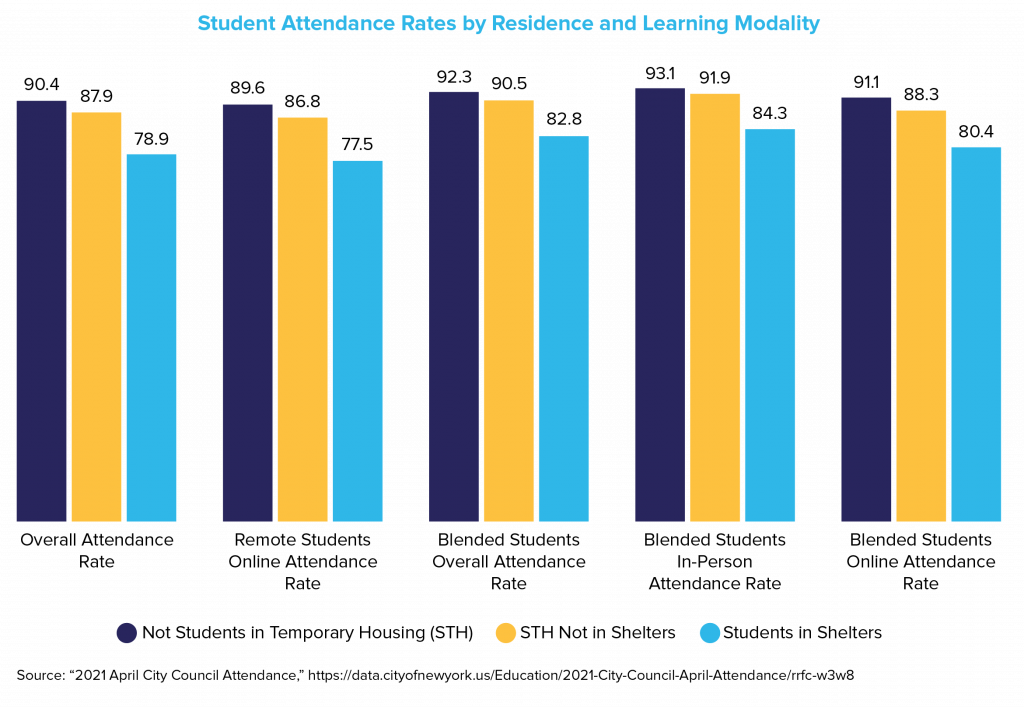

When New York City school buildings closed in March 2020, no one anticipated that the COVID-19 pandemic would persist and that September 2021 would mark the start of a third modified school year. Navigating remote and hybrid schooling over the last 18-plus months has been difficult for all families, but especially so for students experiencing homelessness in shelter, their parents, and the adults who care for them in school and out-of-school-time programs. Students in shelter demonstrated incredible resilience throughout this ordeal. They rose every morning and sat patiently in their rooms alongside their siblings and parents in order to learn or, when school buildings were reopened, traveled to class—sometimes over an hour each way. While the challenges of accessing adequate WiFi service, obtaining working tablets or laptops, and finding quiet spaces for studying in shelter have been well documented, less discussed are the coordination issues between schools and shelters that were present prior to the pandemic and that will continue without significant restructuring.

This article examines how shelter-based student communities fared during this period of upheaval. It highlights both successes and missed opportunities, noting ways that the New York City Department of Education (NYC DOE) can better collaborate with its shelter-based partners to meet students’ needs in School Year 2021–2022 and beyond.

Background on Students Experiencing Homelessness in Shelter

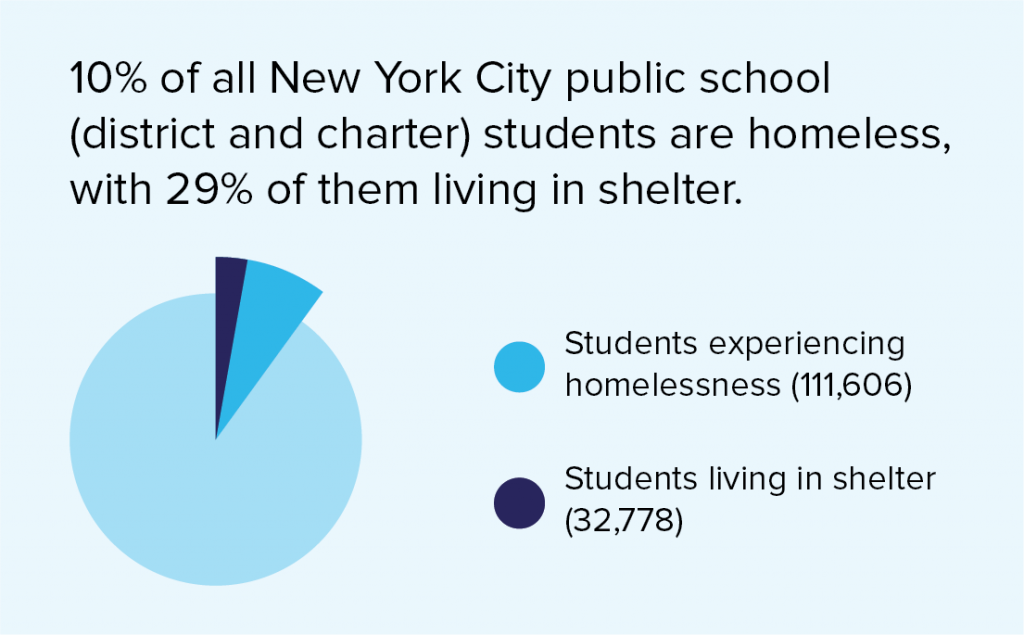

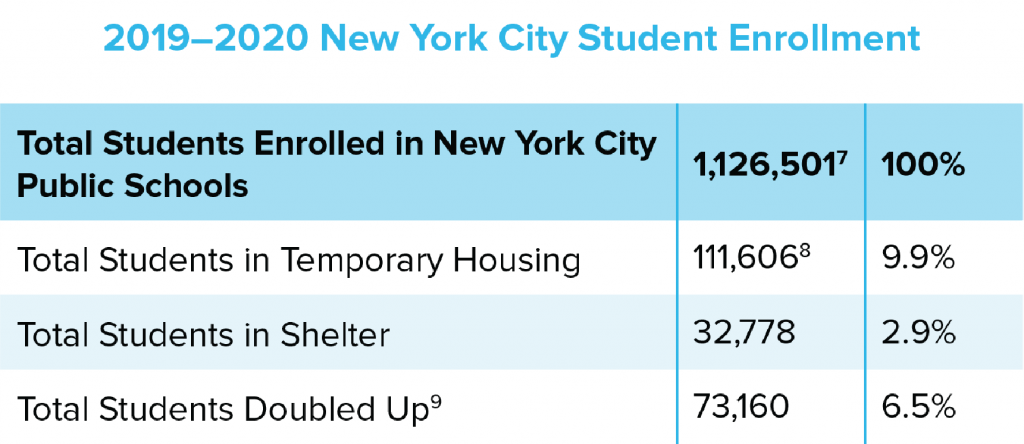

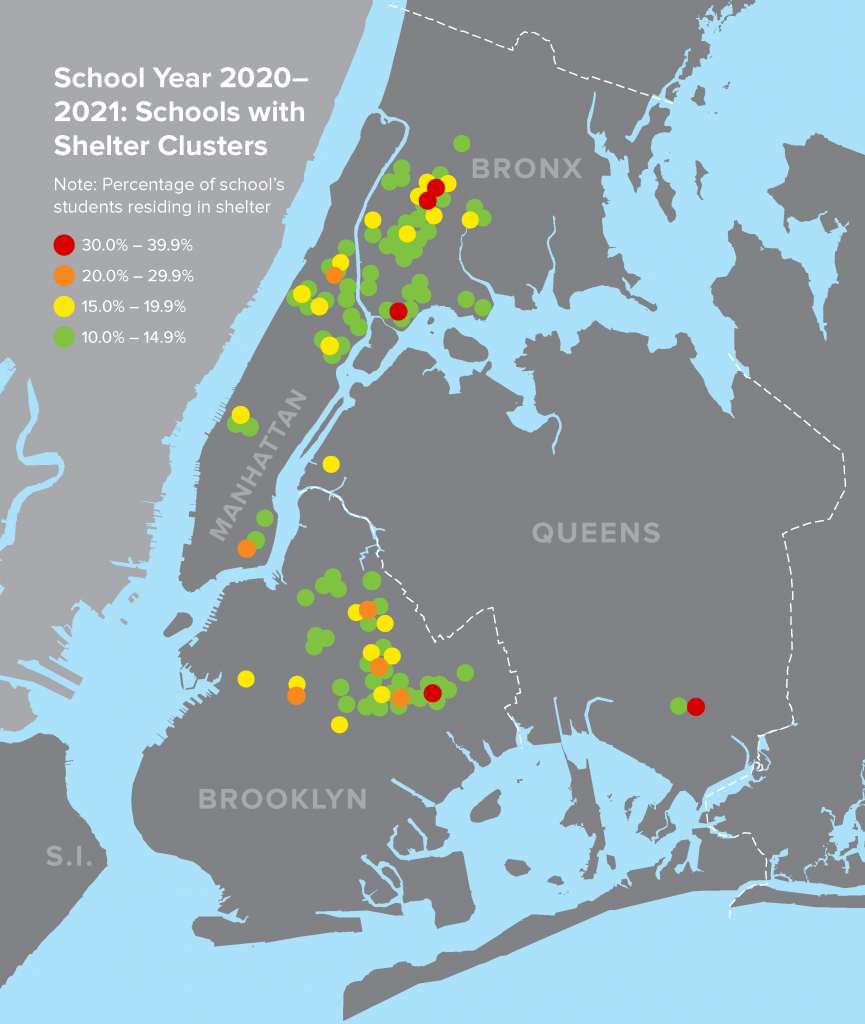

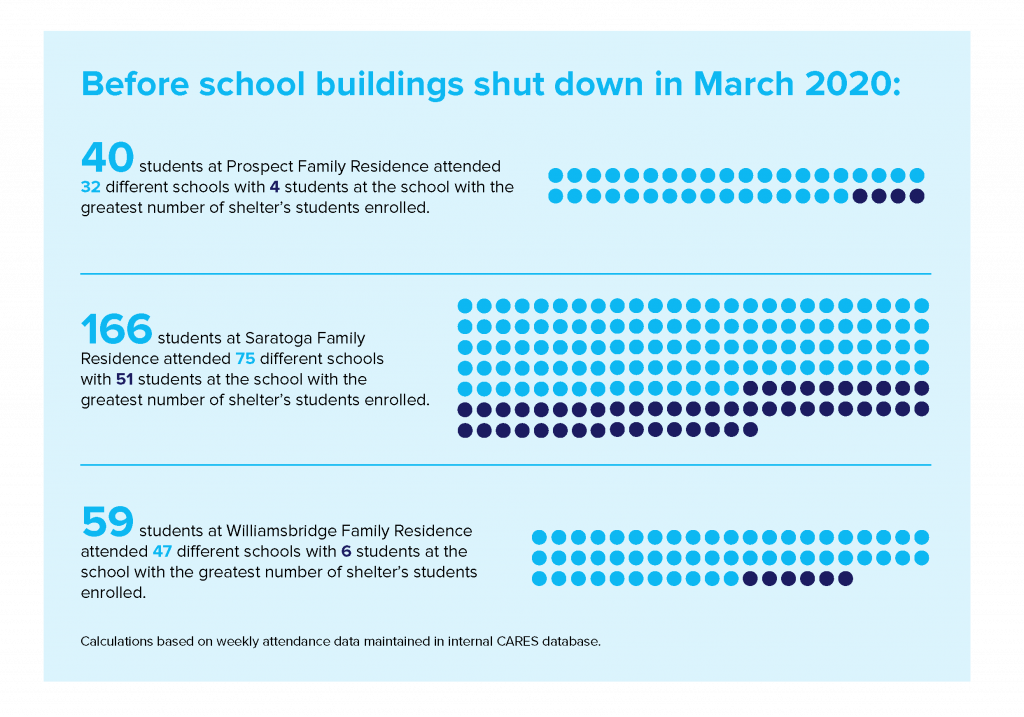

Three percent (32,778) of the total New York City public school population experienced homelessness in shelter during School Year 2019–2020. Another 78,828 students met the federal educational definition of homelessness.1 Students are identified as homeless according to criteria set by the United States Congress and implemented by the United States Department of Education.2 A child or youth who lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence and may be staying in an emergency shelter or transitional housing, at another person’s home due to loss of housing or economic hardship, or sleeping in a place not regularly used for human accommodation, is considered to be experiencing homelessness. In School Year 2020-2021, nearly 42 percent (711 schools out of a total 1690) of NYC DOE-run schools had 11 percent or more of their student body living in some form of temporary housing. And nearly 7 percent of them had 11 percent or more of their student body living in shelter.3

The 32,000-plus students living in New York City shelters each year—over 11,000 students on any given evening4—exceed the entire public-school population of Buffalo, NY, the second-largest city in New York State.5 The right to shelter6 in New York City creates this district within a district, a distinction that the NYC DOE has long recognized by placing dedicated Students in Temporary Housing staff inside shelters to help track attendance, arrange for transportation to school, and liaise between shelter- and school-based staff. Yet even with these supports in place, the pandemic has exacerbated existing gaps on several fronts: Technological Proficiency, Shelter-School Coordination, and Family Engagement.

Clustered Schools for Sheltered Students

Before the onset of COVID-19, students living in homeless shelters scored lower than their housed peers on English Language Arts (ELA) and math tests, transferred schools more frequently, and were disproportionately held back.10 Approximately one-third of students in shelter have been identified as having disabilities and have an Individualized Education Program (IEP).11 When the pandemic hit, the public became increasingly aware of the magnitude of family homelessness and how students experiencing homelessness are dependent on schools for many critical social services, such as meals, clean clothes, social–emotional supports (such as counseling), and physical security.12