By Maribel Maria, Policy Associate, HFH and Robyn Schwartz, Policy Advisor, HFH

Students’ attendance rates are in the spotlight once again, with media highlighting the rising rates of absenteeism among students across New York City and the nation.1 Notably lacking in many news reports is attention to the alarming absenteeism trends among students experiencing homelessness. More than 88,000 students in NYC Department of Education (NYC DOE) schools were considered to be Students in Temporary Housing at some point in the 2021–2022 school year according to the federal McKinney-Vento Homeless Act definition—meaning they lived doubled up, in precarious living situations, or in the shelter system. In this Commentary, we explore available NYC DOE attendance data and the known obstacles homeless students face when trying to make their way to school each morning to help policymakers and stakeholders understand the unique experiences Students in Temporary Housing, and more specifically, Students Living in Shelter face.

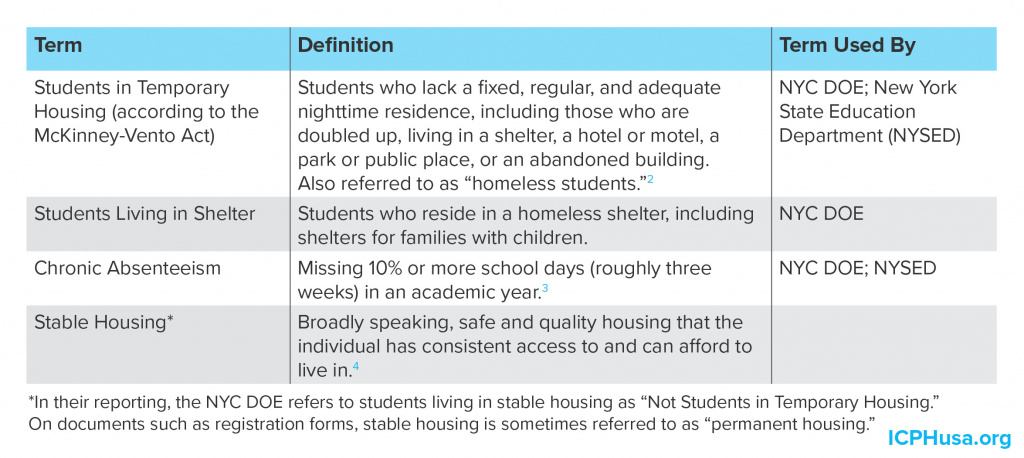

Table 1: Overview of Terms Related to Student Homelessness and Their Use Across Governmental Agencies

[Links to notes 2,3,4]

Local Law 73 (enacted in 2018) requires that the NYC DOE report on the total number of Students in Temporary Housing and break out:

(1) the number of students living in shelters run by the DHS,

(2) the number of students living in shelters run by other agencies [Human Resources Administration (HRA), Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD), Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD)], and

(3) the number of students living “doubled up” with friends or family members because they cannot afford their own housing.

Attendance has long been a struggle for Students in Temporary Housing (STH) as a whole. In the 2021–2022 school year (the year for which data is most recently available), 54% of New York City’s district-run public school Students in Temporary Housing were considered chronically absent, much higher than the 45% of all students in poverty and the 39% of stably housed students who were chronically absent.5,6 Unlike the Local Law 73 student enrollment reports that are disaggregated by living situation, attendance data is not disaggregated in this manner.7 This means that groups working with Students Living in Shelter or other housing circumstances do not have access to information specific to those they serve.8 Though this meaningful measure is lacking, it is still noteworthy that Students in Temporary Housing overall have higher rates of absenteeism than their stably housed classmates.

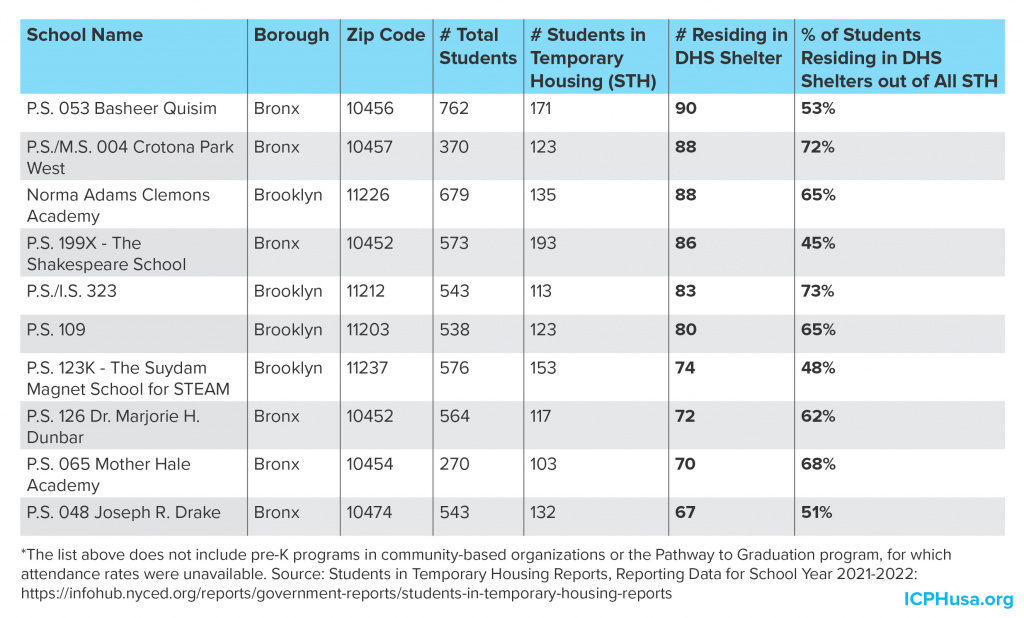

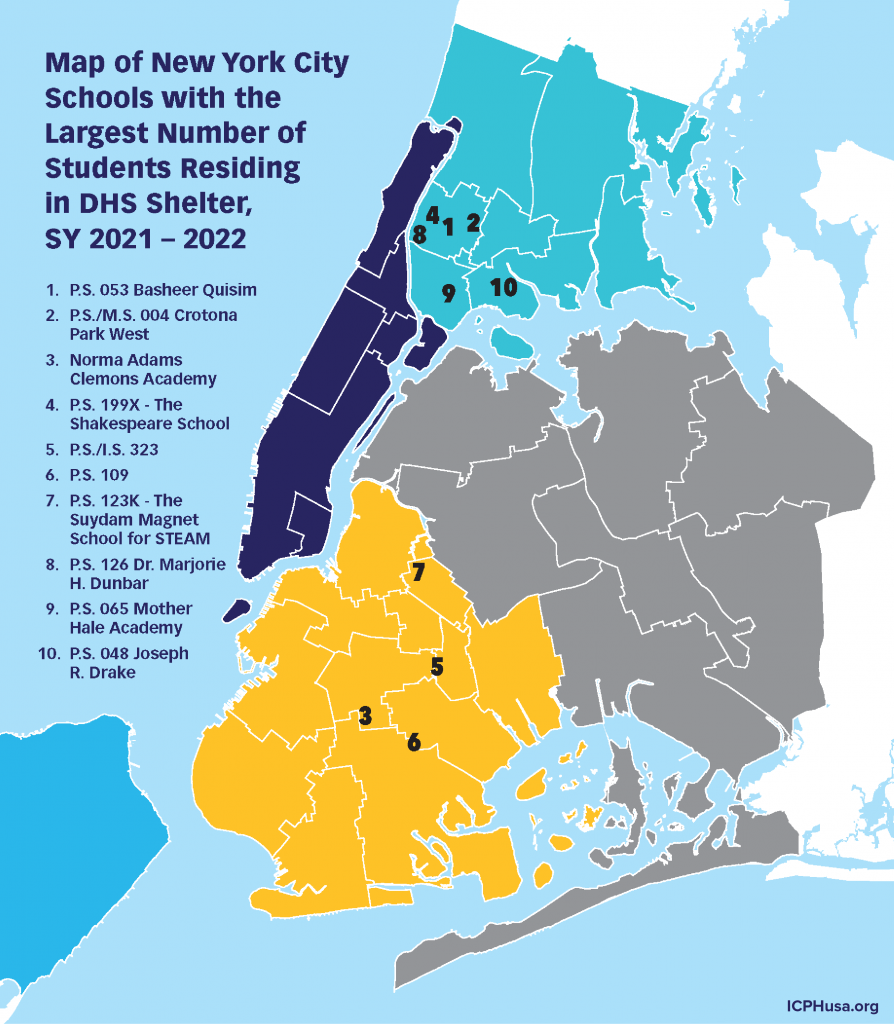

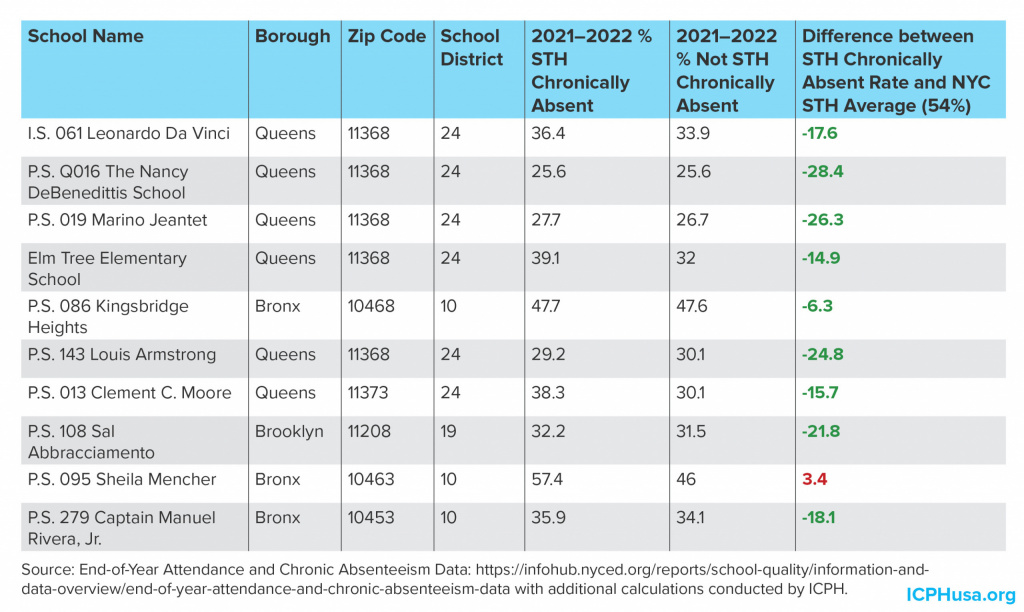

To navigate the lack of attendance data specific to Students Living in Shelter, we reviewed data available for the 10 NYC DOE district-run public schools with the highest number of students living in DHS shelter. In these schools, the percentage of students residing in DHS shelters out of the school’s overall population of Students in Temporary Housing ranged from 45% to 73%. Upon determining that nearly half or more of their Students in Temporary Housing population lived in DHS shelter, we considered it appropriate to use this attendance data to further investigate the disturbing trend of poor attendance rates among students in DHS shelter.

Table 2: New York City District-Run Schools with the Largest Number of Students Residing in DHS Shelters, SY 2021 – 2022*

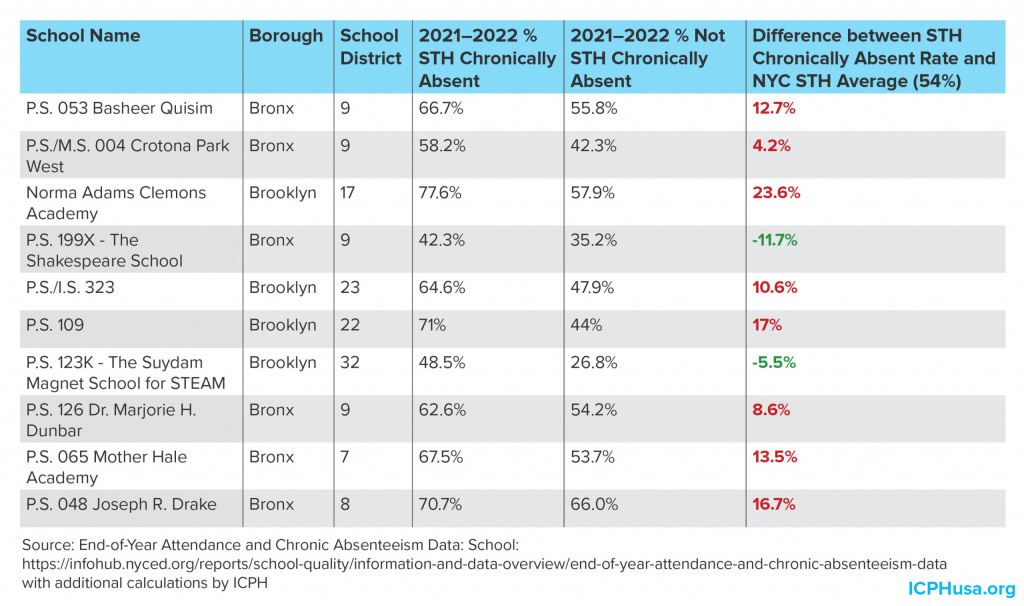

In the 2021–2022 school year, Students in Temporary Housing in these 10 schools were more likely to be chronically absent than their stably housed peers. Two schools, P.S. 199X – The Shakespeare School in the Bronx and P.S. 123K – The Suydam Magnet School for STEAM in Brooklyn, had absenteeism rates for Students in Temporary Housing below the city’s average of 54%. Notably, these two schools had the smallest share of Students Living in Shelter among their overall STH population.

Table 3: Chronic Absenteeism Rates in Students Living in Temporary Housing and Students Not Living in Temporary Housing, SY 2021– 2022

It is also of note that the schools with the largest number of students living in DHS shelters are in the Bronx and Brooklyn. Four of the six schools located in the Bronx are also in the same district—District 9, which encompasses Grand Concourse, Morrisania, and Tremont—neighborhoods in the western portion of the South Bronx.

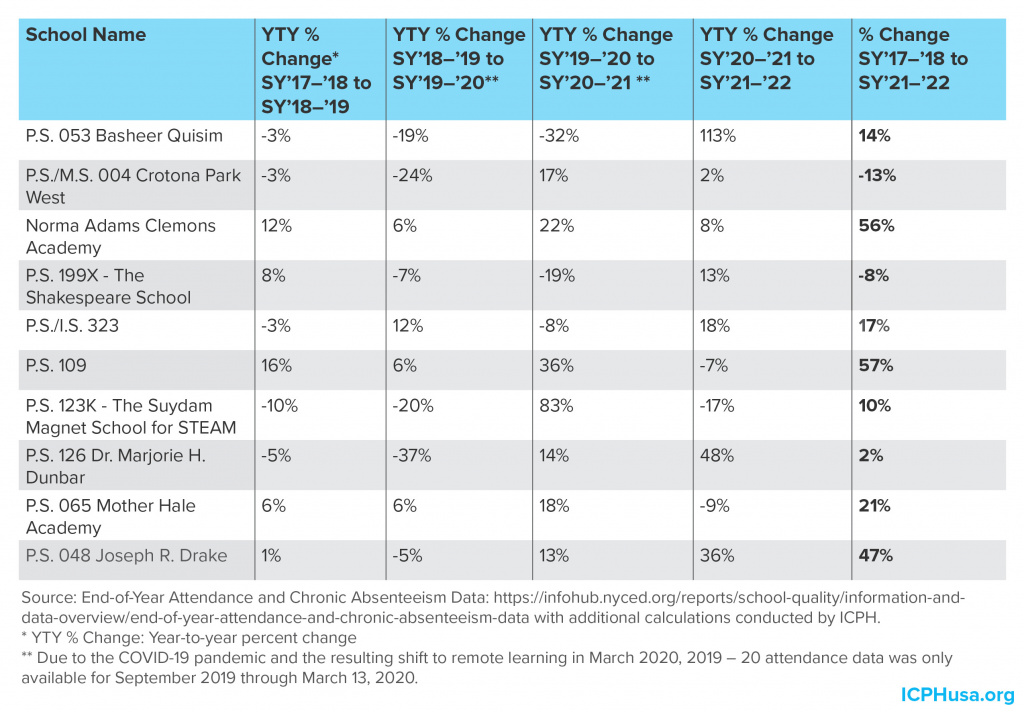

Students are considered chronically absent when they miss 10% or more school days in an academic year.9 Attendance can be a crucial indicator of a student’s level of engagement with their school and local community. One school, P.S. 053 Basheer Quisim, saw the absenteeism rate more than double between the 2020–2021 school year and the 2021–2022 school year, notably the school years during which students transitioned from attending school hybrid or remotely to returning to the classroom. The chronic absence rate in eight of the 10 schools listed above increased between the 2017–2018 school year and 2021–2022 school year, demonstrating that attendance continues to be a concerning issue across the city’s schools. Only two schools, P.S./M.S. 004 and P.S. 199X, both located in the Bronx, saw their chronic absenteeism rates drop when comparing the 2017–2018 school year to the 2021–2022 school year.

Table 4: Percent Change in Chronic Absenteeism Rates in Students Living in Temporary Housing, SY 2017– 2018 to SY 2021–2022

We also reviewed data available for the 10 NYC DOE district-run schools with the highest number of Students in Temporary Housing overall. Because three of the schools were high schools and the schools we examined with the highest DHS shelter population were all elementary or middle schools, we opted to eliminate the three high schools from our analysis and take the next three middle or elementary schools with the greatest number of Students in Temporary Housing (ranging from 477 to 229—all greater than the schools with the highest population of students living in DHS shelter). In these 10 schools students are overwhelmingly classified as living doubled up.

Table 5: Chronic Absenteeism Rates in Students Living in Temporary Housing and Students Not Living in Temporary Housing, SY 2021– 2022

These schools have marked differences from the previously discussed schools with the highest population of Students Living in Shelter. Six of the 10 schools are in Queens District 24, which encompasses the neighborhoods of Ridgewood, Maspeth, Glendale, Middle Village, Elmhurst, Corona, Woodside, Long Island City, and Sunnyside. This section of Queens is home to a diverse group of new immigrants. The remaining four schools are in Bronx District 10 (three schools) and Brooklyn District 19 (one school). Bronx District 10 covers Fordham, University Heights, Morris Heights, Bathgate, Bedford, Belmont, Riverdale, and Mount Hope while Brooklyn District 19 serves East New York, Cypress Hills, Starett City, City Line, and Spring Creek. All but one school (P.S. 095 Sheila Mencher in the Bronx) had STH chronic absence rates much lower than the citywide STH rate. P.S. 095 Sheila Mencher had an STH chronic absence rate of 57.4%, more than three percentage points higher than the citywide STH rate.

Notably, all but two schools saw an increase in their STH chronic absence rate from SY2017–2018 to SY2021–2022. District 24 encompasses the areas of western Queens that were hit particularly hard in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Five of the six schools in Queens are located in Zip Code 11368, which had a COVID death rate of 619.73 per 100,000, higher than the boroughwide death rate (448.39) and the death rate for New York City as a whole (407.55).10 So it would not be surprising for chronic absence rates to climb in communities struggling to recover from such trauma. One school in that community, P.S. 143 Louis Armstrong, had their SY2021–2022 STH chronic absence rates return to their SY2017–2018 levels.

Exploring High Absenteeism Rates

As mentioned previously, available NYC DOE attendance data does not separate information by specific living conditions. Understanding that Students in Temporary Housing are not a monolithic group, the following exploration seeks to add context to the issue of chronic absenteeism among homeless students by looking particularly at those living in shelter.

A shelter’s location can often impact a student’s ability to get to school. Under the McKinney-Vento Act, children have a right to continue attending the school they attended before entering shelter.11 Many families in shelter (nearly 75% during School Year 2021–2022) exercise this and other rights guaranteed under McKinney-Vento to keep some stability in the child’s life.12 However, families are often placed in shelters far from their child’s school due to reasons such as local capacity or the need for distant placements due to a domestic violence case. Other families may opt to have the child switch schools to ensure they are closer to the shelter. When a child’s commute drastically changes, returning to a typical routine is cumbersome and frustrating, further hampering their ability to get to school. Historically, the chronic absenteeism rate among Students in Temporary Housing has been higher than that of their stably housed peers. Still, it is also important to note the lasting effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ attendance and overall experience in school.13

As seen in Table 4, chronic absenteeism rates in six of the 10 schools listed were trending downward in the school year before the beginning of the pandemic. Many students, including those in shelter, experienced significant learning disruptions due to adjustments their schools had to make during the early months of the pandemic. The pandemic exacerbated many of the existing challenges that Students Living in Shelter faced in attaining an education, like consistent access to reliable technology. Students may have also had trouble focusing during remote learning, as they had to complete classwork in shared rooms with their families. In addition to issues of distraction, remote work often felt less engaging to many children and their parents.14 As students returned to the physical classroom, they brought back the trauma, frustrations, and disengagement that may have grown during the height of the pandemic and remote learning.

Potential Consequences of Chronic Absenteeism

Chronic absenteeism has potentially severe consequences for learning for all children, particularly for children experiencing homelessness. Most school-aged children living in DHS shelter are in elementary school.15,16 Of the 10 schools indicated in Tables 2 – 4, seven serve students from pre-K to 5thgrade, with the remaining three serving students from pre-K to 8th grade (both groups include special education). As most students living in DHS shelters fall into these grades, the importance of attendance during these early school years cannot be overstated. Early education and elementary school provide foundational speaking, reading, writing, mathematics, and problem-solving skills.17 Early academic access and achievement are strong indicators of a homeless student’s future success and ability to stay out of shelter when they enter adulthood.18 Though the skills and grades attained in secondary school are those considered in admittance to higher education programs, these would be nearly impossible to achieve without the basics covered in students’ early years.

Thus, chronic absenteeism can influence outcomes throughout a student’s life. When homeless students miss a significant amount of their school year, they are more likely to be held back a grade and less likely to graduate in the future.19 As higher education attainment helps alleviate poverty and prevent future entrance into shelter, missing a significant amount of school can leave students at a disadvantage into adulthood.20

High absenteeism rates among homeless students (those living in shelter or other accommodations) create vast issues for them beyond academics. Homeless students often rely on their schools as sources of material resources like meals and social services like counseling, as well as community and stability that can help them navigate the complexities of experiencing homelessness.21 Being chronically absent can have negative health effects on homeless students, as schools are commonly a consistent source of healthy meals. Homeless students are less likely to eat breakfast or fresh fruits and vegetables than their stably housed peers.22 Missing school further exacerbates this inequity and keeps homeless students from accessing this crucial resource.

When students miss school, they not only miss out on academic enrichment but also lose opportunities to socialize with peers, connect with staff, and participate in extracurricular activities. Homeless students can often feel disconnected and that they lack support outside of their families.23 The community that homeless students build by being present and actively engaged in their schools can be crucial to their emotional wellbeing and help foster a sense of stability. Consistent school attendance can allow teachers and staff additional touchpoints to observe students and see if they require extra academic or emotional-behavioral support, ensuring that school remains a stable and engaging place for homeless students.

Helping Students Living in Shelter Get to School

For Students Living in Shelter, it is apparent that families, the NYC DOE, and DHS shelter staff all have essential roles to play in supporting students in attending school and succeeding in their educational journeys. It is crucial to prioritize students’ needs to provide them with the help they require, such as transportation support, anchored by effective communication between schools, shelters, and families. The McKinney-Vento Act entitles students to transportation to the school they attended before becoming homeless.24 However, it is challenging to coordinate bus routes, whether to a student’s school of origin or the school to which they transferred.25 As families enter and exit shelter, available busing support changes depending on current routes. Dedicated coordination between schools and students’ families is essential. If routes are unavailable, a student can use their MetroCard, available to all Students in Temporary Housing, to travel to school. Parents can also qualify for monthly MetroCards to cover transportation costs to accompany their children to school but must make this need known to NYC DOE staff.26 Navigating these resources requires those involved to share information and coordinate among themselves to ensure students’ needs are promptly identified and addressed.

Shelters and schools can play a pivotal role in this communication and relationship-building by focusing efforts on hiring and retaining culturally competent and skilled staff. Communication between families and the school and shelter-based employees tasked with supporting them is most meaningful when conducted in the primary language that a family speaks and with staff with whom the family has grown familiar over time.27 Such consistent and trustworthy exchanges can further encourage families to speak up about their children’s educational needs.

NYC DOE staff placed in shelters (Family Assistants and Community Coordinators) are poised to play a particularly key role in helping Students Living in Shelter reduce their absences. After lengthy advocacy efforts the NYC DOE augmented the number of shelter-based staff, though funding is tenuous after FY2024 when the bulk of the (federal) funding for the positions runs out. In order to gauge the impact of having additional shelter-based staff focused on better connecting children to their schools, it will be important to disaggregate STH chronic attendance data by student living situation for SY2022–SY2023 and beyond so the public can see if this investment has led to marked improvement in school attendance for Students Living in Shelter.

While additional linkages inside shelters are welcome, efforts made by schools with a large population of Students Living in Shelter should also be examined. In the analysis above, there were two schools with large populations of Students Living in Shelter, P.S. 199X – The Shakespeare School and P.S. 123K – The Suydam Magnet School for STEAM, that had Students in Temporary Housing absenteeism rates below the city’s STH average of 54%. While the reasons behind their better performance as compared to the city average and the other schools reviewed may be unclear and warrant further investigation, it is possible that they may have programs or policies that other schools can replicate to improve their own attendance rates. P.S. 199x – The Shakespeare School has a dedicated “Students in Temporary Housing” section (under the “Families” menu) on its website.28 Clear contact information is listed for the STH Coordinator and School Social Worker along with a Google form that families are asked to fill out weekly. The form asks what families need support with that week (for example, access to food pantries, transportation, teacher contact information, etc.). Such an outreach effort builds consistency and trust and may very well encourage and support children in attending school more regularly. Dialogue among schools serving large numbers of Students Living in Shelter can bring forward creative solutions that can be applied widely.

It is reassuring that there is increasing awareness of general attendance issues in the country’s schools. However, the solutions implemented must not make sweeping generalizations about the needs of all students. Navigating the unique needs of Students Living in Shelter deserves the attention and cooperation of families, schools, and shelter staff to ensure students can thrive.

1 National Public Radio, School attendance still isn’t what it was before COVID, New York Daily News, Chronic absenteeism climbs to record numbers in NYC schools

2 Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, Frequently Asked Questions

3 New York State Education Department and Children’s Aid Society, Tackling Chronic Absence

4 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Healthy People 2030: Housing Instability

5 New York City Department of Education, End-of-Year Attendance and Chronic Absenteeism Data, Information provided by the NYC DOE only consists of data from district-run public schools and excludes charter schools.

6 New York City Department of Education, Students in Temporary Housing Reports, The NYC DOE defines students in temporary housing as “students experiencing housing instability at any point, for any length of time, during the school year (from the first day of school to 7/2). This includes students and families that are “doubled up” (sharing the housing of others due to economic hardship), living in shelter (including NYC Department of Homeless Services family shelters or Human Resources Administration domestic violence shelters), or living in some other unstable, temporary housing.”

7 New York City Council, Int. No. 1497-A, Requiring the DOE to report on students in temporary housing

8 New York City Department of Education, Students in Temporary Housing Reports

9 New York State Education Department and Children’s Aid Society, Tackling Chronic Absence

10 New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, COVID-19: Data Neighborhood Data Profiles; NPR, Councilman Says Many In Queens, NYC’s Hardest-Hit Borough, Can’t Afford Burials

11 New York City Department of Education, Students in Temporary Housing

12 New York City Department of Education, Students in Temporary Housing Reports

13 Homes for the Homeless, Snapshot: Back to School 2021–2022

14 Homes for the Homeless, Snapshot: Back to School 2021–2022, p 1

15 Department of Homeless Services, DHS Data Dashboard Table FYTD 2023, from Stats & Reports

16 Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, What You Need to Know About NYC’s Homeless Elementary School Students

17 New York City Department of Education, Elementary School Learning

18 Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, The Lasting Academic Impact of Homelessness

19 Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, Empty Seats: The Epidemic of Absenteeism Among Homeless Elementary Students

20 Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, About ICPH

21 Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, School Instability Factors

22 Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, No Longer Hidden: The Health And Well Being of Homeless High School Students

23 Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, The Importance of Fostering Positive School Climates for Homeless High School Students

24 The New York State Technical and Educational Assistance Center for Homeless Students, Transportation

25 Homes for the Homeless, Snapshot: Back to School 2021–2022

26 Advocates for Children of New York, Guides & Resources: Arranging Transportation Services

27 Gateway Housing, Attendance Matters: A Model Program Pilot

28 The Shakespeare School P.S. 199X, Students in Temporary Housing