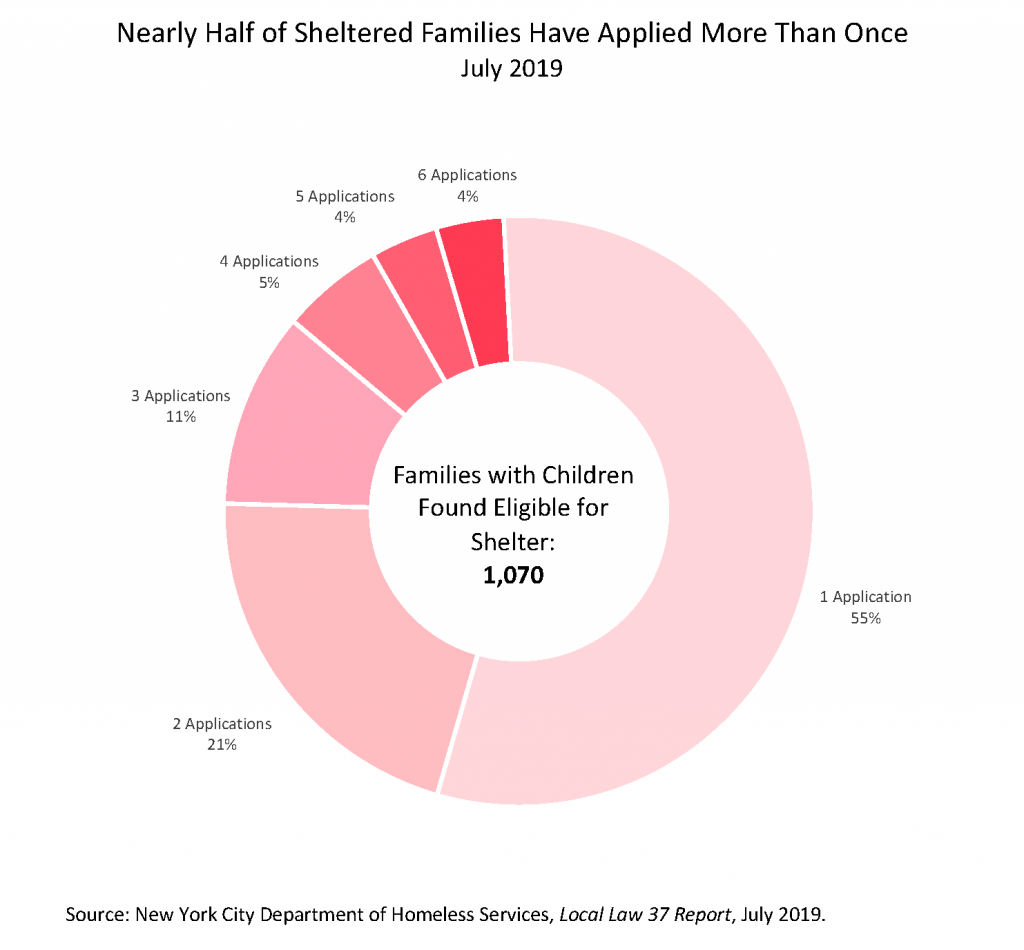

By July 2019, the most recent month of available data, there were over 11,800 families with over 23,000 children sleeping in New York City shelters—a 49% increase since 2011. Every month, over 2,000 families apply for shelter from across New York City, yet only around 40% of them are deemed eligible for shelter. For many of these families, the path to shelter is not straightforward—about half have to apply at least twice before receiving their eligibility determination. This cycle of applications exacerbates the instability experienced by parents and their children, and often leaves them with no choice but to return to potentially unsuitable living conditions while they reapply for shelter.

The City has worked hard to provide sufficient shelter capacity—currently about 13,800 shelter units are available to homeless families—and to increase the stock of available low-income housing. However, little systemic consideration has been given to the factors that make families susceptible to housing instability in the first place, nor to the implications that such instability can have on the health and well-being of children in these families. Both data and experience suggest that a child-focused approach would help reduce the trauma of the shelter application and reapplication processes on families, and alleviate the negative impact of housing instability on a child’s education and well-being.

The First Step Toward Shelter

While New York City is one of the only cities in the country where all eligible families and single adults have a legal right to shelter, it is by no means a given that a family will be found eligible for shelter. All families seeking shelter are required to apply at the Department of Homeless Services’ (DHS) intake center, called the Prevention Assistance and Temporary Housing center, or PATH. Currently, well over 100 families apply for shelter at PATH each day.1

When a family arrives at PATH, the first step is meeting with a Human Resources Administration (HRA) Caseworker whose role is to assess whether the family can be diverted from shelter by connecting them with public benefits and/or social services to help them return to prior housing or identify other non-shelter options. If the family continues with the shelter application process, they receive a conditional shelter placement while their eligibility is being determined. The eligibility process looks at a two year housing history to determine whether the family has any viable, safe, and suitable non-shelter housing options to which to return. While the eligibility investigation is supposed to last up to 10 days, it is not uncommon for the process to be extended for multiple weeks. Of those families who apply for shelter at PATH, a significant number are found ineligible. Most recently, in July 2019, 59% of families (over 1,500 families) who applied were found ineligible for shelter.

The Often Arduous Path to Shelter Eligibility

DHS may find a family ineligible for shelter if it determines the family has viable, safe, and suitable non-shelter housing available or if it is unable to verify any part of a family’s reported housing history from the previous two years. For example, a family may not be able to provide DHS with the required documentation, including identification, birth certificates, and proof of all housing history. Additionally, shelter applicants will receive an ineligible determination if the dates they claim to have resided with a family member do not align with the dates provided to the DHS Family Worker by that family member.

Applicants are also found ineligible if the Family Worker believes a family member or friend could provide them with a place to stay. However, beyond a serious safety issue (such as domestic violence or otherwise unresolveable discord), there is little consideration as to whether these relationships may be exhausted by the time a family reaches PATH.

Eligibility determinations are communicated to families through a written notice, sometimes slipped under the door of their conditional placement during the night. If a family is deemed ineligible, they must vacate their room the next morning. For many families who maintain they have nowhere else to go, this means another trip directly back to PATH to reapply.

Does Ineligibility Stop a Family From Knocking at the Shelter Door?

Available data on shelter eligibility indicate that for many families the shelter application process does not end when they are deemed ineligible. Rather, families may reapply at any point, including immediately after receiving their ineligibility notice. Yet if the family was found ineligible for having alternative housing and cannot prove a change in circumstance from the prior application, they are not assigned to a conditional placement during the 10 days their new application is reviewed. In that case, they must find a place to stay outside of shelter while the reapplication is reviewed.

Nearly half of all families who were found eligible for shelter in July 2019 had applied multiple times during the previous three months before they were found eligible. For some families, eligibility was finally determined because circumstances at their primary residence deteriorated during the application process to the point where they were ultimately found in immediate need of shelter. For others, the need for multiple applications was process related—either the family had insufficient documentation or the PATH investigation was unable to confirm the family’s housing history. Regardless of the reason a family reapplies for shelter, the effects of this ongoing instability are detrimental to the family’s— particularly the children’s—well-being. Importantly, persistent housing instability can have long lasting consequences on a child’s health and education, resulting in feelings of depression, sleep deprivation, missed school time, and trouble concentrating in the classroom.

Why Managing Shelter Access Is Not Enough

One-third of all individuals currently residing in a New York City shelter are under the age of 18. These children are highly susceptible to the negative effects of housing instability and as a result face many challenges to their education and overall health. In SY 2016–17, over half (56%) of all students in shelter were chronically absent and nearly one-third (31%) transferred schools mid-year. In addition to experiencing school instability, these students are at heightened mental health risk—nearly half (47%) of high school students living in shelter reported being depressed and half (50%) reported that they attempted suicide. For these children, applying for shelter as many as six times before becoming eligible only adds to the stress and instability already present in their lives, and could exacerbate problems common among homeless students, such as absenteeism, tardiness, disciplinary issues, and mental health concerns.

Undoubtedly, DHS and HRA have the difficult task of sheltering a growing homeless population, stretching already limited resources to serve those families who are found to be in immediate need of shelter. While DHS is the point of coordination for all eligibility and shelter services, most homeless families have contact with several City agencies both before and during their experience with housing instability. Many have already been linked to these agencies through their schools, afterschool programs, Administration for Children’s Services (ACS) involvement, or community health clinics. It will be essential to leverage the resources and expertise of those not only within DHS and HRA, but within agencies such as the Department of Education, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, the Department of Youth and Community Development, and ACS with the objective of supporting families before they find themselves at the critical point of applying for shelter.

While New York City already has multiagency coalitions working to address homelessness, these efforts have primarily focused on single adults. Given that individuals in families make up almost two-thirds of those in shelter, it is time to place this vulnerable population at the forefront of this multiagency approach to tackle the family homelessness crisis in New York City.

1Per the DHS Daily Reports, the number of families with children applying for emergency shelter every day can vary from a low of 60 to a high of 150.