June 2014

New York City has many tales to tell, and while one may be “of two cities,” another is about two kinds of students: the housed and the homeless. Today there are over 80,000 homeless students in the city’s school system. They fill seats in classes from kindergarten through 12th grade, and their future is anything but promising. When compared with students in the general population, homeless students fare far worse in a number of areas important to their success in school and beyond.

This report takes a look at the plight of homeless students in the New York City school system. It identifies their academic and behavioral challenges, the impact of homelessness on their performance in school, and their probable outcomes by 12th grade. The report also offers alternative approaches to helping homeless students compete and achieve academically and measures the cost of failure against the possibilities of success.

A “Left-Back” Generation

Each year the number of homeless students in New York City’s public schools grows, increasing by close to 60% in the last six years alone. Homelessness in the city has become an epidemic, affecting every school district in every borough and threatening the chances for a generation of poor children to succeed in their academic and adult lives. On practically every measure of achievement, homeless students perform poorly, signaling a cost to the city in both lost potential and dollars spent. In school year (SY) 2011–12 alone, the city paid millions of dollars to educate homeless students who were required to repeat a grade. Unless we understand and address the problem, today’s homeless students are at risk of becoming a “left-back” generation—the next generation of homeless families, with children of their own failing in school and filling tomorrow’s shelters.1

Challenges In and Out of Class

Children will not perform well in school if they do not arrive ready and able to learn. But the frequency with which homeless students’ families move from one form of temporary housing to another makes even getting to school a challenge.

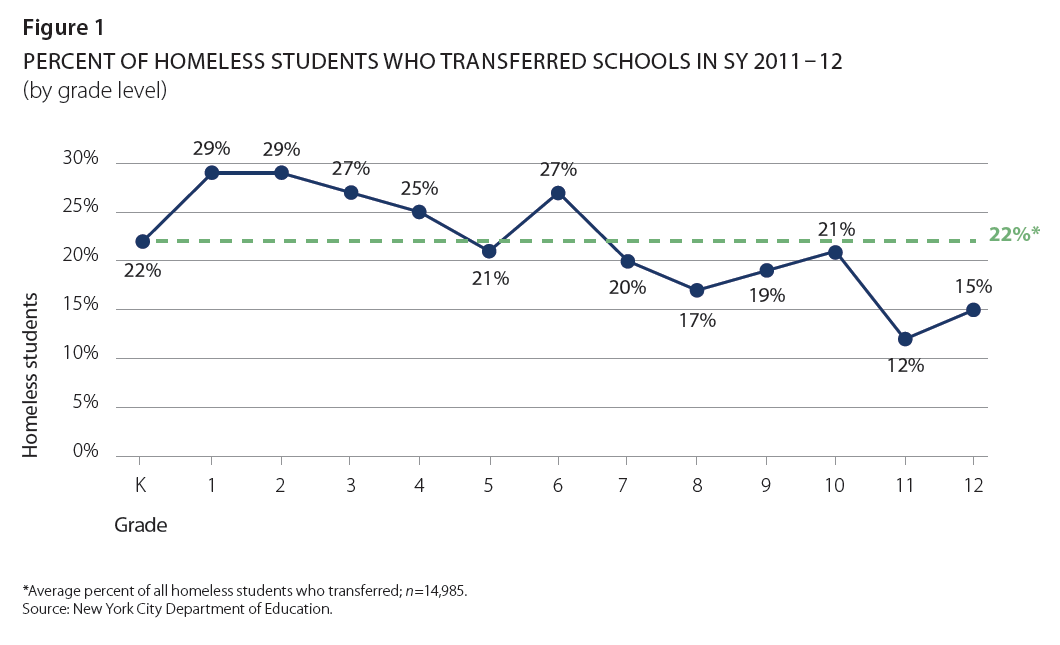

Frequent moves mean frequent changes in school enrollment, with more than one out of five homeless students (22%) transferring schools at least once (Figure 1) and an estimated 18% transferring two or more times in a single year.† Changing schools disrupts children’s education, setting them back academically up to six months for every transfer. Homeless students who transfer schools more than once in a year can quickly fall a grade or more behind their peers.2

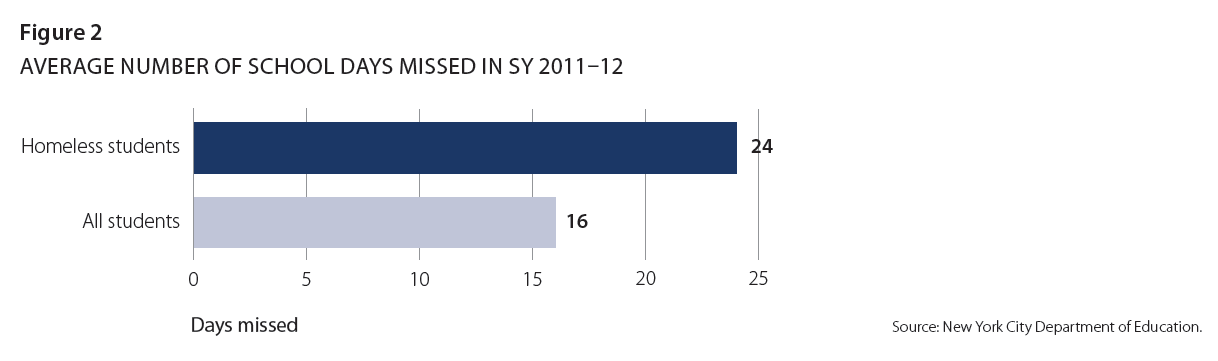

Homeless students also attend school at lower rates, missing, on average, over one month of school annually. In absolute terms, they attend school at rates below the minimum targeted by the Department of Education for grade promotion, increasing the probability of repeating a grade (Figure 2).3

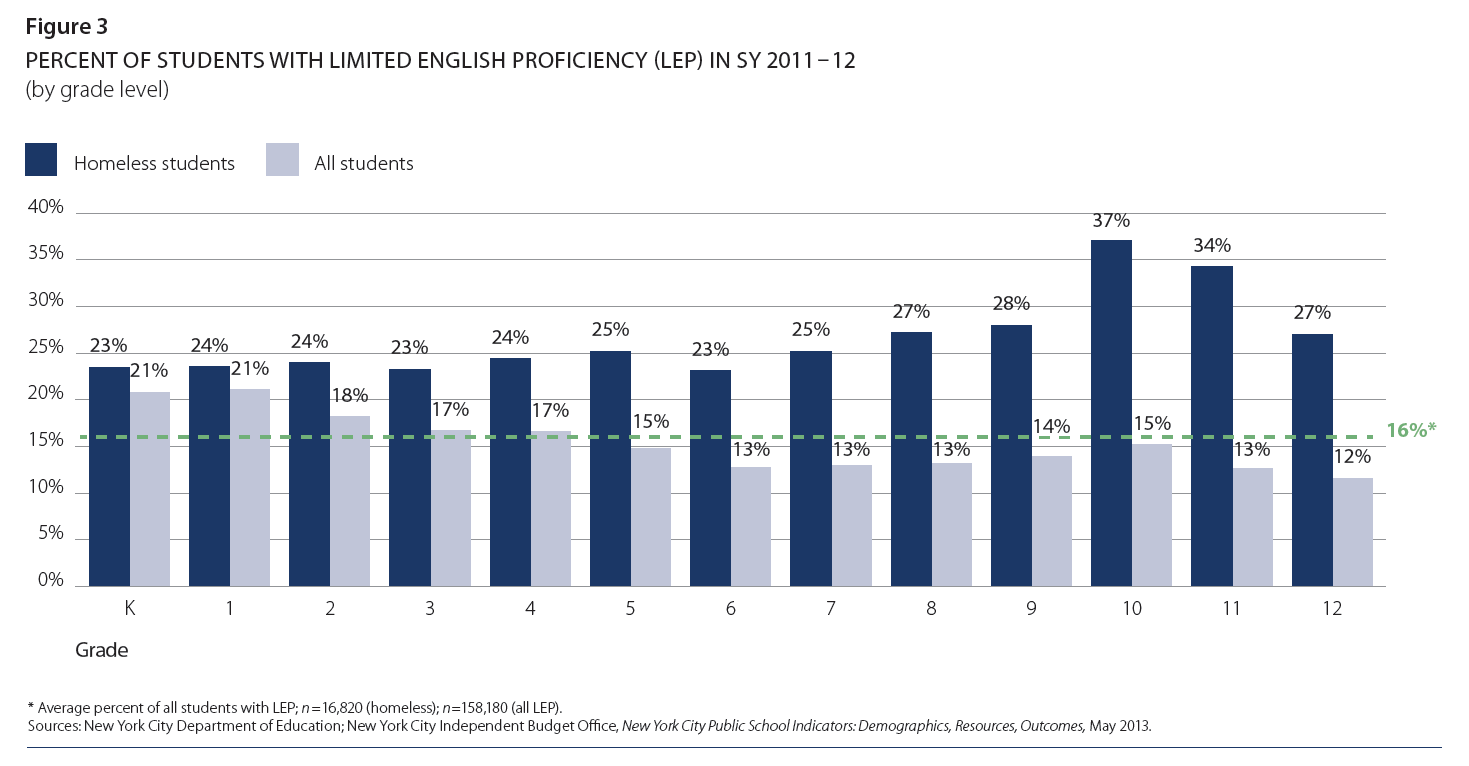

Challenges extend beyond just getting to school. For homeless students who are English Language Learners, the failure to address their needs early on further compromises their ability to keep pace with their non-homeless peers. Depending on grade level, between 23% and 37% of homeless students are classified as having Limited English Proficiency. These percentages are much lower for all students, varying from 12% to 21%, and the disparity persists across every grade, becoming even more pronounced in later years and peaking in the tenth grade, where the difference is 22 percentage points (Figure 3).

Falling Behind

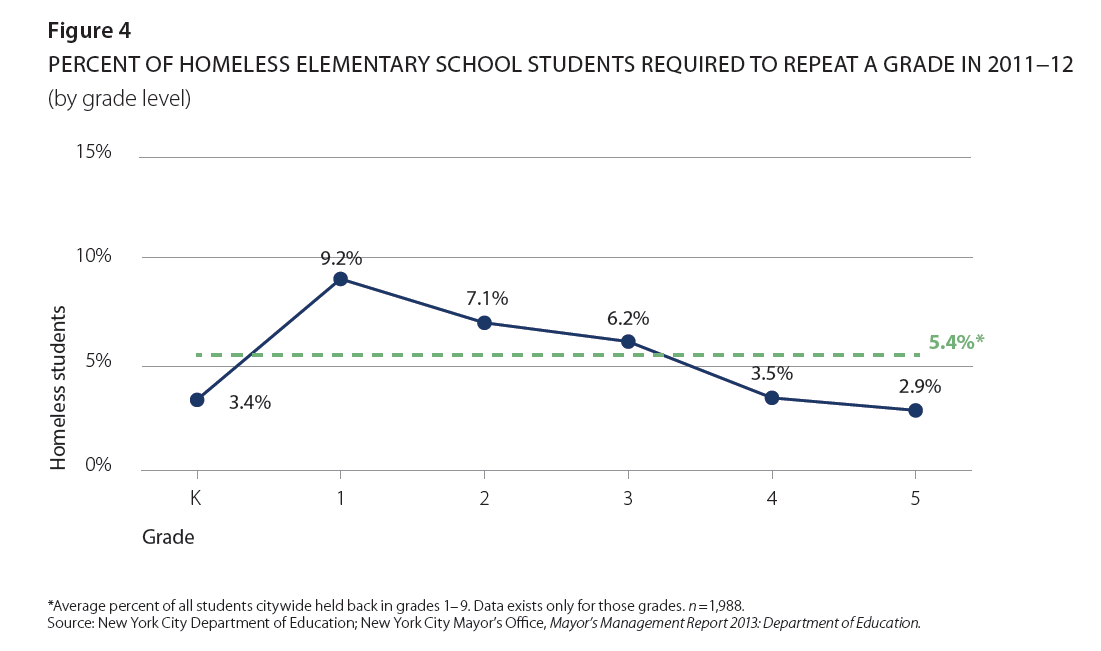

Homeless children enter elementary school at a disadvantage. It is estimated that as many as three-quarters of homeless children under age six in New York City are not enrolled in high-quality early childhood education programs. When compared with their non-homeless peers, these students are less prepared for kindergarten, and in first grade close to one in ten is held back—a rate nearly double that of all students (5%) in first through ninth grades (Figure 4).4

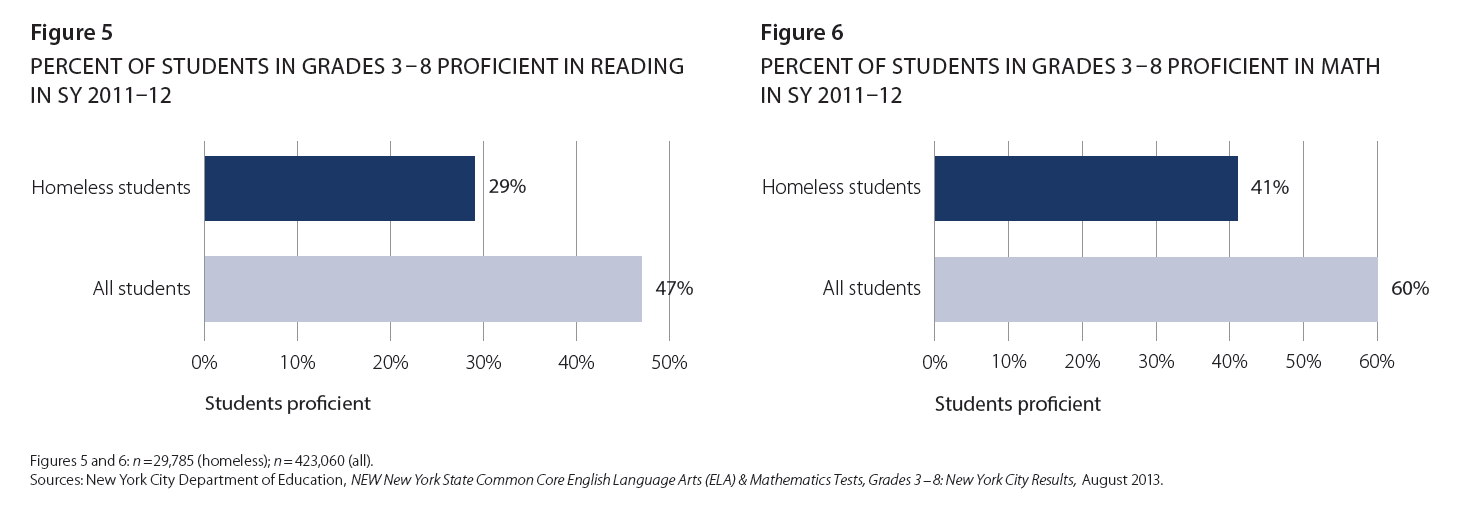

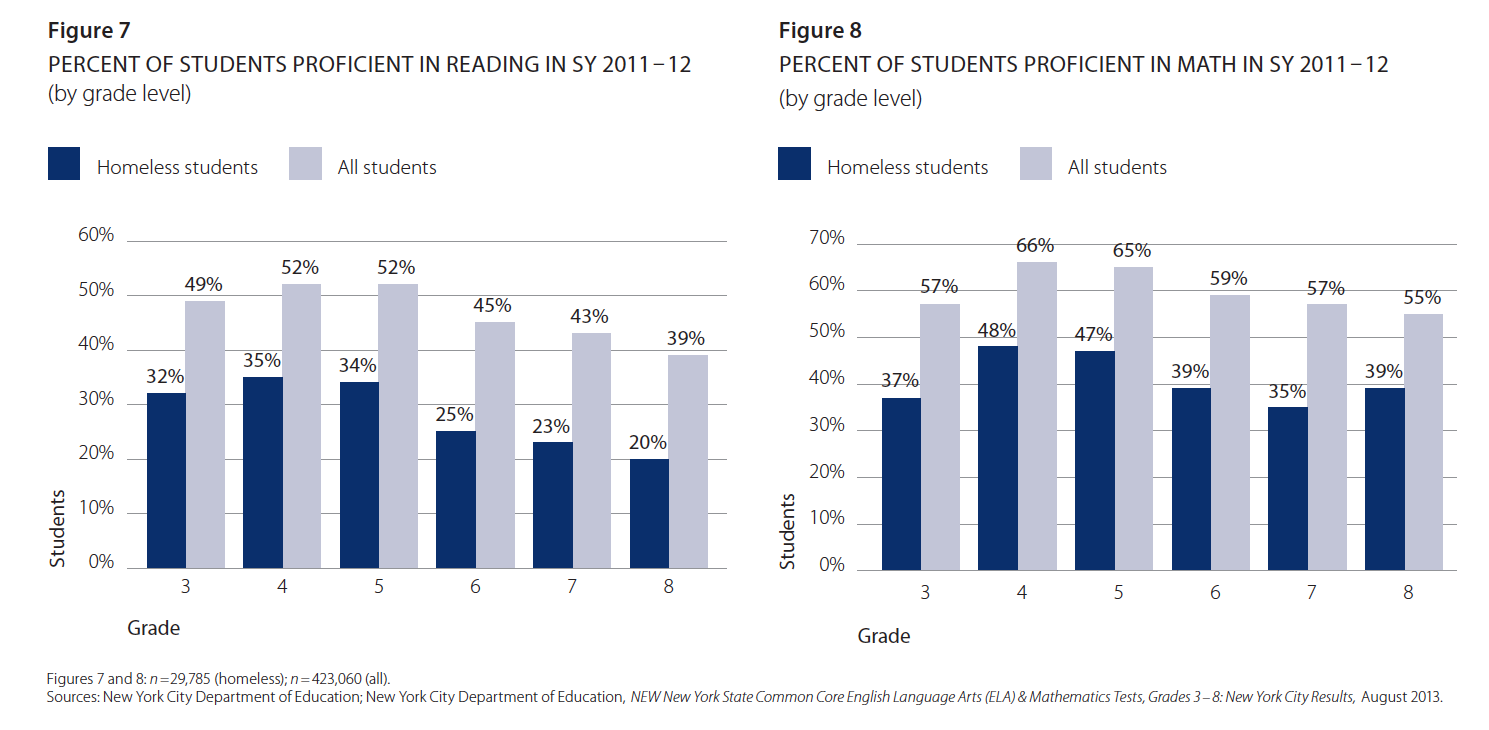

In elementary and middle school, homeless students score more poorly on their third- through eighth-grade English Language Arts exams, with only 29% reading at grade level, compared with 47% of all students (Figure 5). Similar gaps exist in math. Only 41% of homeless students were proficient in math, versus 60% for all students (Figure 6).

Moreover, as students experience homelessness in middle school, their test scores decline. In eighth grade only 20% are proficient in reading, compared with 39% of all students, and 39% are proficient in math, compared with 55% of all students (Figures 7 and 8).

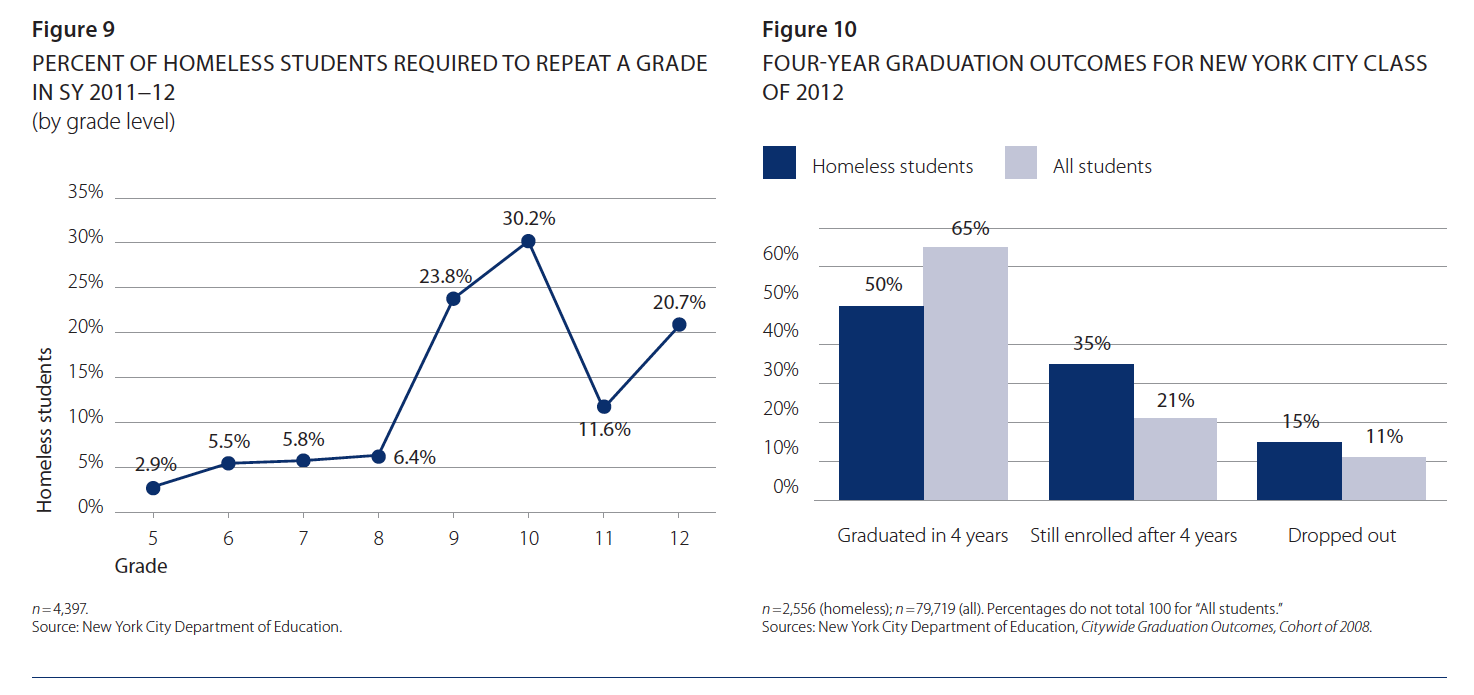

Homeless students’ low test scores in elementary and middle school indicate a severe lack of preparedness for high school. In ninth grade 24% of homeless students are held back, and by tenth grade the rate increases to 30% (Figure 9). After four years in high school, only 50% of homeless students graduate on time, compared with 65% of all students; 35% remain enrolled and 15% drop out (Figure 10).

The Cost of Failure

Educating a single child in New York City’s public school system costs over $21,000 annually. In the 2011-12 school year, 6,273 homeless students had to repeat a year of school, at an estimated cost of $135 million. Additionally, homeless students who repeat grades are at greater risk of dropping out of high school, with a number of negative results. For example, nationally, female dropouts overall are six times more likely to become young (under age 24) parents and nine times more likely to be single mothers than women with college degrees. Since women who do not graduate from high school earn, on average, roughly $13,255 a year, these young single mothers will have fewer resources to support their families, making them 2.5 times more likely to rely on public assistance, at a cost of $8 billion per year nationally. High school dropouts also make up the majority of the nation’s prison inmates. The cost of interning an inmate in New York City is $168,000 annually. (It is estimated that if male high school graduation rates increased by 5%, New York State could save up to $967 million annually in crime-related costs.) With the city’s homeless student population at a record high, the financial costs associated with failing to address their educational needs will only increase as more students are left back and/or drop out of school.5

Bringing It Home: Alternative Approaches

There are policy initiatives designed to help homeless students achieve. In one of the city’s large family shelters, a full range of programs to meet the educational needs of homeless children is underway and achieving success. The services include high-quality pre-K, early education, and after-school programing, which provide homeless children with the resources needed to compete in school effectively. The key component of these initiatives is that they take place in the shelter and are open to the surrounding community. This ensures accessibility for homeless families and fosters educational continuity for children, since they can continue to participate in programs even after their families are no longer in residence at the shelter.

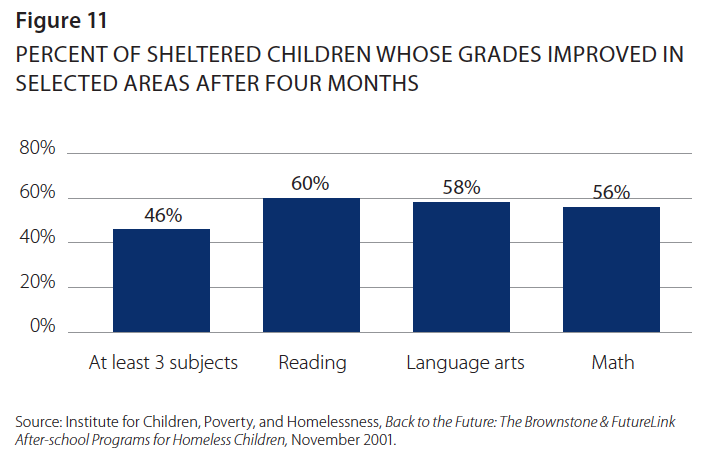

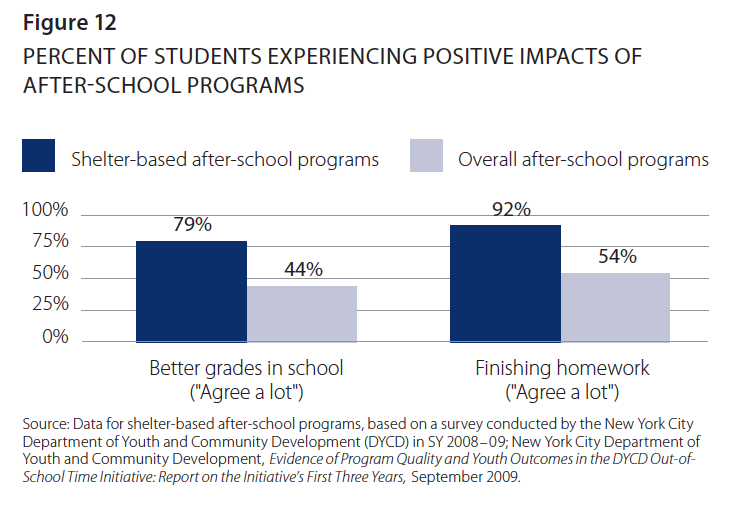

High-quality early education has been shown to support positive outcomes, making it less likely that children will require special education services, repeat grades, or be dependent on public assistance later in life. In fact, while homeless children entered these programs less prepared than their housed peers, they experienced large cognitive and socio-emotional gains, improving more rapidly than their peers. Shelter-based after-school programs have been shown to improve educational outcomes for children who have already entered elementary, middle, or high school. In one study, close to 60% of students who participated in such after-school programs for more than four months saw improvements in reading, language arts, and math, 79% reported that program participation helped them get better grades in school, and 92% said they finished their homework more often (Figures 11 and 12). Moreover, these types of programs can cost as little as $3,000 per year, per student. When the long-term cost of children’s falling behind in school is taken into account, providing shelter-based after-school programs in addition to existing school-based after-school programs presents an opportunity for enormous cost savings.6

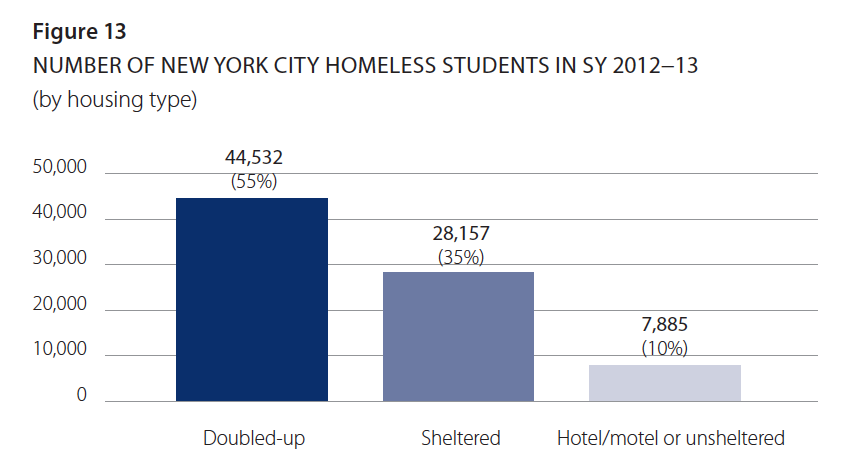

In addition to improving educational outcomes for homeless children and creating cost efficiency, shelter-based education programs have locations that allow them to reach large numbers of these children. In the 2012–13 school year, 28,157 school-age children (Figure 13) and more than 18,000 children under six resided in the city’s 158 family shelters. For these roughly 50,000 homeless children, creating shelter-based education programs would ensure accessibility by establishing services where they live. With the average stay in shelter now exceeding 429 days, rather than simply providing a place to stay, shelters can be transformed into powerful tools and a stabilizing force in homeless children’s lives—supporting their education and mitigating the chaotic experience of being without a permanent home.7

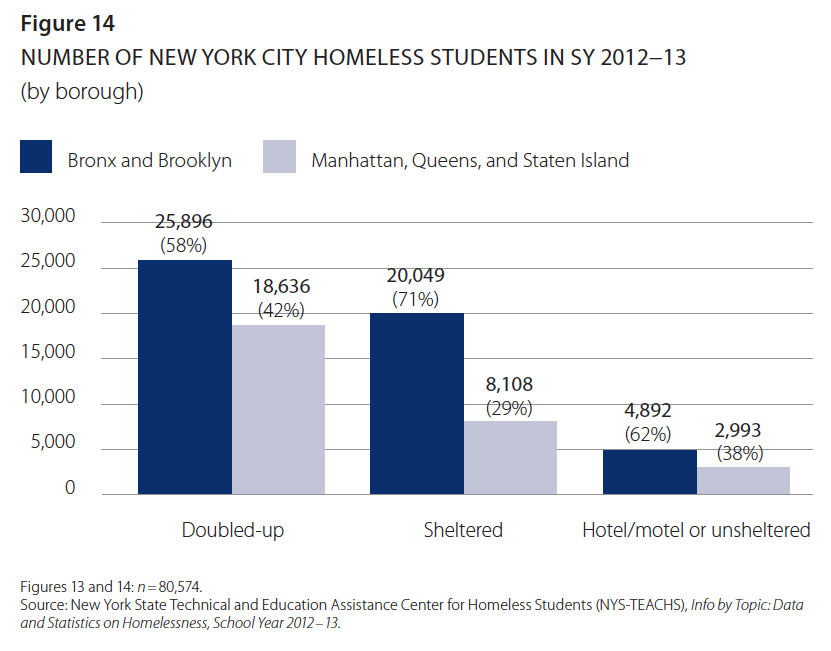

For homeless students who do not live in shelters and struggle with even greater instability—living doubled-up, in hotels, or on the street—shelters are still practical locations for programs. This is particularly true for the boroughs of the Bronx and Brooklyn, where close to two-thirds of the city’s family shelters are located and also where the majority of homeless children living doubled-up reside (Figure 14). Shelters can be transformed into residential community resource centers, serving not only the thousands of homeless families and children who live there, but also those in the communities where shelters are located. For students living doubled-up, additional city initiatives including universal pre-K, after-school programs for all middle-schoolers, and an expansion of the Community School initiative have great potential to address the needs of homeless students.8

Conclusion

This report has noted the many challenges homeless students face. They are absent more frequently, transfer schools at higher rates, perform more poorly on tests, are left back more often, and have worse graduation outcomes. Family shelters now house more children than adults. Placing high-quality day care, early education, preschool, and after-school programs in shelters is a cost-effective way to meet the educational needs of thousands of homeless children who are at risk of being held back or dropping out of school. A family’s entry into shelter represents an opportunity for New York City to identify homeless children who may be falling behind in school and to help them succeed educationally. Improving education is essential, and providing programs in shelters is a logical place to start. By making efficient use of their space and infrastructure and bringing together funding for education programs from various city agencies, shelters—as residential community resource centers—can help to rebuild struggling neighborhoods, address the underlying causes of homelessness, and help guarantee that New York City’s homeless children do not become today’s “left-back” generation and tomorrow’s generation of homeless families.