By Maribel Maria, Policy Associate, HFH and Robyn Schwartz, Policy Advisor, HFH & ICPH

Reference Table of Relevant Terms

Early Education and Care

3-K for All (3-K): Free educational programming for three-year-old children in New York City.

EarlyLearn NYC: New York City early education program that currently offers free or low-cost childcare for children between six weeks and two years old. In its original iteration, it also sought to standardize the overall City-supported childcare system.

Head Start: Federally funded programs that deliver services to low-income families, such as free educational services for children between three and five years old.

New York City Early Education Centers (NYCEECs): Community-based education centers independent of the New York City Department of Education.

Pre-K for All (Pre-K): Free educational programming for four-year-old children in New York City.

Project Giant Step: New York City early education program that sought to bring universal care to four-year-olds. Operated from 1986 to 1990.

Subsidized childcare: Free or low-cost childcare programming that is funded by federal, state, and/or city funding.

SuperStart: New York City education program that targeted services to children from low-income families. Operated from 1990 to 2008.

Government Agencies and Departments

Administration for Children’s Services (NYC ACS): New York City government agency that promotes the safety and well-being of children and families.

Agency for Child Development (ACD): Precursor to Administration for Children’s Services (NYC ACS).

Board of Education (BOE): Precursor to Department of Education (NYC DOE).

Department of Education (NYC DOE): New York City agency that manages the city public school system.

Human Resources Administration (HRA): New York City agency that administers over a dozen social services programs.

New York State Education Department (NYSED): State system of educational services that supervises public schools and oversees education standards and assessments, among other responsibilities.

Legislation

Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA): 2015 reauthorization and amendment of the 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). Promotes strategies for educational equity through support to schools. Replaced No Child Left Behind (NCLB).

McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act: Federal law created to support the identification, enrollment, and education of students experiencing homelessness.

No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB): 2002 reauthorization and amendment of the 1965 federal Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). Enacted to improve school and student performance.

Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA): 1996 federal law that provided time-limited assistance contingent on fulfilling work requirements. Replaced Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) with Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).

Family Homelessness

Right to Shelter: Legal concept that states a locality must provide emergency housing to anyone who requests it.

Tier I: Shelters that provide minimal accommodations and services in congregate settings.

Tier II: Shelters that provide private accommodations and services such as permanent housing preparation, recreation, information and referral services, health services, and childcare.

Family Welfare

Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC): Federal program that provided states with funds to provide cash payments for children whose families had low or no income.

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF): Federal program that provides states with funding for support programs for low-income families.

Key Takeaways

- As of March 2023, nearly 46% of persons under 18 living in DHS shelters were 0 to five years old.

- Before early education and care programs were commonly available in New York City, communities loosely organized daycare among themselves. The need for childcare grew as more women entered the workforce in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s.

- Early education and care programs have taken one of two approaches: targeting children of lower-income families or universally serving children of all income levels.

- Early education and care programs and policies in New York City have undergone frequent shifts since the 1980s, mostly tied to changes in mayoral administrations and ideological trends. Among these ideological trends are changes in perceptions of public assistance, welfare, and work requirements.

- New York City-funded early education and childcare programs for ages 0 to three years old do not release figures regarding the number of enrolled children experiencing homelessness, making it difficult to fully understand how many children in early education and care programs are experiencing homelessness.

- Parents and children experiencing homelessness benefit from participating in programs like 3-K and Pre-K for All, but only if program design and execution are sensitive to their unique needs.

- Regardless of intention, early education programs have often done a disservice to working families and families experiencing homelessness due to issues such as limited extended day and year seats. This can especially add to the existing burdens families in shelter may face in meeting work requirements to qualify for certain public assistance programs.

- Under-enrollment resurfaces throughout the history of early education and care programs. Recent issues with enrollment can be tied to program design, and not to a lack of need in areas being served, as the limited number of extended day and year seats can end up excluding many who would benefit from early education and care services.

- Recommendations for improvements to the early education and care system in New York City that would better serve homeless families with children include:

- diminished administrative burden in application and enrollment practices for families,

- increased transparency in application and enrollment practices, and

- increased data collection and reporting, especially data disaggregated by living situation.

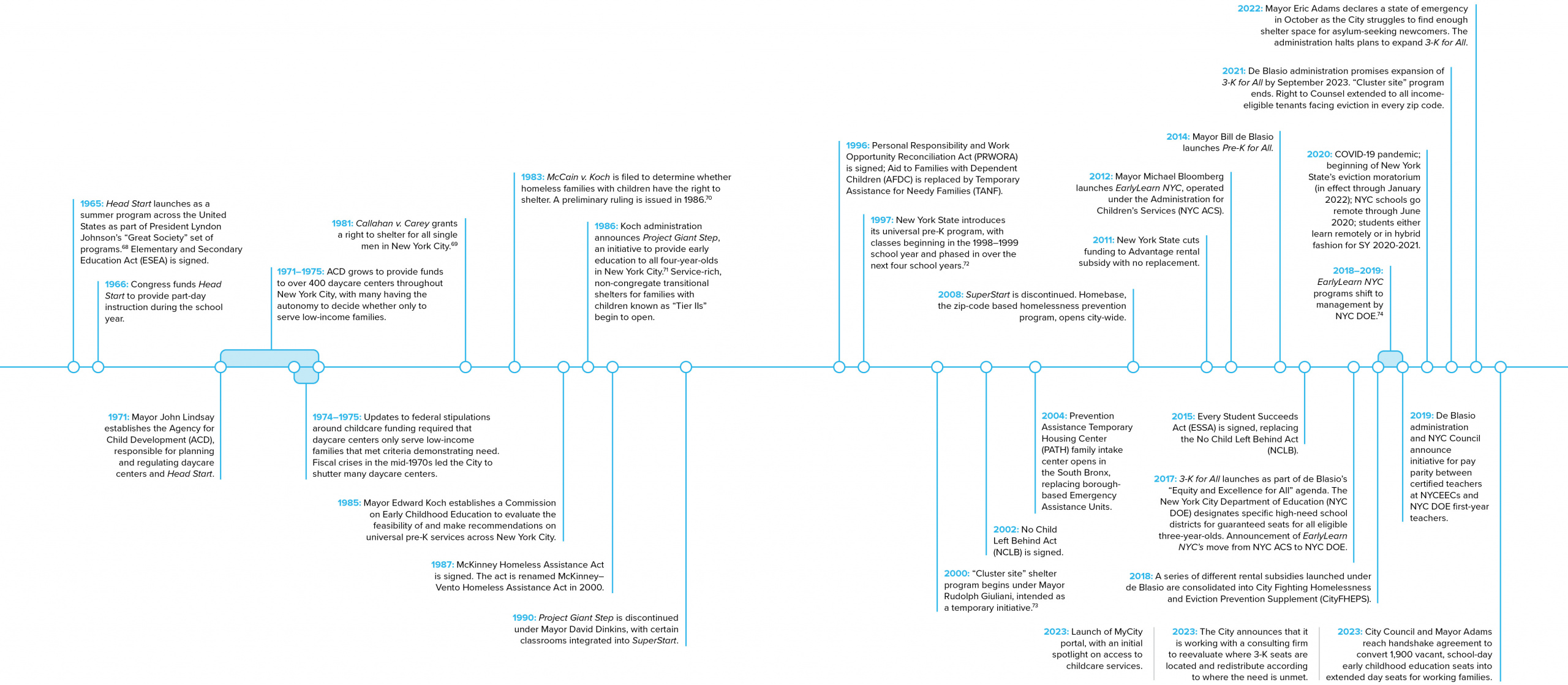

TIMELINE: The Trajectory of Early Education & Childcare and Family Homelessness in New York City: 1960s–Today

Click timeline to enlarge or download PDF HERE.

Click timeline to enlarge or download PDF HERE.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

Introduction

New York City’s leaders often highlight the city’s image as a national pioneer in accessible early childhood education and care.1 Despite the great successes of the most recent iterations of early childhood education, 3-K (for three-year-olds) and Pre-K for All (for four-year-olds), complications have excluded some families who many experts say would benefit most from participating.

Parents and children experiencing homelessness stand to gain from participating in programs like 3-K and Pre-K for All, but only if program design and execution are sensitive to their unique needs. In April 2023, after Mayor Eric Adams announced a reduction in 3-K seats while consultants advised on how to right-size the system, The New York Times examined why 30,000 early education slots remained empty.2 Among the data included in the article was that following the COVID-19 pandemic, the enrollment rate in pre-K for four-year-olds living in shelter had dropped from nearly two-thirds to 50 percent.3 The article did not speculate as to why the numbers dropped, and no one at the Department of Homeless Services (DHS) or the New York City Department of Education (NYC DOE) addressed the challenges faced in ensuring that children living in shelter have access to early education programs.

Family homelessness in New York City has reached record numbers. As of June 1, 2023, 15,898 families with 27,015 children were living in shelters run by DHS.4 As of March 2023 (the period for which data is most recently available), nearly 46% of persons under 18 living in DHS shelters were ages 0 to five years old.5

Since the emergence of family homelessness as a major social issue in the 1980s, policymakers and advocates have been concerned about adequate supervision and access to educational services for children living in shelter. Early childcare services in homeless shelters are regulated by New York Codes, Rules, and Regulations, Title 18, Chapter II, Subchapter L, Part 900 (commonly referred to as the Part 900 regulations). The regulations apply to Tier II facilities, or service-rich shelters which provide a comprehensive set of supports to residents. Among other rules concerning the operation of shelters, the regulations state that care must be provided by the shelter and utilized by parents when necessary to “seek employment and/or permanent housing or to attend school or training.”6

According to data from the New York State Education Department (NYSED), during School Year 2021–2022, there were 6,001 pre-K students in NYC DOE district-run and charter schools identified as having experienced homelessness at some point during the school year.7 Not all of these students were living in DHS shelters, as the definition of student homelessness according to the federal McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act includes all children “who lack a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence.” Students identified as experiencing homelessness could be living in emergency or transitional shelters such as those run by DHS, but they could also be living doubled up with family or friends due to economic hardship, precariously living in motels, hotels, trailer parks, or campgrounds, or sleeping unsheltered in places unfit for human habitation.8 The youngest grade band for which New York State tracks student homelessness is pre-K. At the same time, NYC DOE does not publicly release rates of homelessness by grade band, so equivalent figures are not available for students in the City’s 3-K program. Additionally, City-funded (either through vouchers or direct contract) childcare programs for children ages 0 to three years old do not release figures on the number of enrolled children experiencing homelessness. Without each of these data points, it is difficult to get a complete picture of the number of children ages 0 to five years old not yet enrolled in kindergarten who are experiencing homelessness. That information could be used to craft policies that ensure both quality early education and wraparound childcare so that children are ready for elementary school and their parents have the support needed to work and move out of shelter or shared housing.

As the goal of building an even more inclusive early education and care system is still in sight, reflecting on the history of early education in New York City can bring perspective to its current challenges. Earlier this Spring, the Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York released The Youngest New Yorkers, a report examining the more recent history of early education and care in New York City and what barriers remain for families trying to access care.9 ICPH wanted to build on this foundational work to look even further back at the evolution of the City’s early education and care system alongside the trajectory of family homelessness, changes in public assistance, and provision of care and education. By tracking the history of the City’s efforts in this arena, it is possible to offer fact-grounded recommendations to policymakers focused on improving access to early education and care programs. Among the recommendations for system improvements that can best assist families experiencing homelessness are more data and increased transparency, as well as diminished administrative burden in application and enrollment practices that considers the unique needs of working homeless families.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

Laying the Groundwork: Early Education and Care in New York City Before the 1980s

Prior to the 1980s, family homelessness was not yet recognized as a significant social problem in New York City, although plenty of families struggled economically. The first iteration of federal welfare assistance came about in 1935. Established as part of the Social Security Act, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) allowed states to distribute cash payments to families with children who had an absent, unemployed, incapacitated (and unable to work), or deceased parent.10 States had great flexibility (within parameters set by the federal government) to determine cutoff levels for aid, and the system remained relatively stable from inception until the 1960s, when the first experiments with work requirements and training programs were initiated.11 Amid this backdrop, women entered the workforce in larger numbers during the 1940s, 50s, and 60s, so a growing need emerged for access to childcare.12 When childcare for low-income working families couldn’t be provided by extended relatives or neighbors, many in New York City turned to a limited number of childcare centers primarily operated by social welfare or religiously-affiliated organizations where women of color especially took a role in organizing care.13 By the late 1960s, many of these centers had crumbling infrastructure that had not been updated since the 1940s. Some families addressed this need by loosely organizing daycares across the city, allowing parents to place their kids in community-based daycare. However, this loose network of childcare options led to centers that varied in quality.14

In 1971, NYC Mayor John Lindsay created the Agency for Child Development (ACD) under the Human Resources Administration (HRA), establishing and regulating daycare and Head Start programs.15 Federal funds were available for childcare as local and national government officials started to see education as a means of lifting families out of poverty and removing mothers from the welfare system.16,17 Using funding from the federal government, Mayor Lindsay tapped childcare advocates, many of whom were part of the earlier movement to establish daycare centers in the loose structure noted above, to help build up a more standardized network that could serve children in the areas with the greatest need. This collaboration between government and community leaders led to the establishment of higher-quality facilities, which often housed daycares and social service organizations alike. Standards of quality during this time were highly influenced by studies such as the Perry School Project and the Carolina Abecedarian Project, which viewed “high-quality” as routine, interactive classroom experiences led by college-trained early educators. The studies also deemed parental involvement and access to other social services as crucial to program success.18 These interventions continue to impact how the quality of early education programs is defined.19 In addition to more concrete ways to define quality, the programs established in New York City reflected the cultural shifts that had been building up over the decades, with many women seeking to eliminate gender norms that confined them to care for children in the home.

Launched in the mid-1960s as a key part of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society programs to fight the War on Poverty, Head Start programs are federally funded and operate locally to deliver services to “the most vulnerable young children” and their families. Programs specifically target children from low-income families and provide free learning services to children between three and five years old.20 In order to qualify for services, families must be found eligible according to one or more criteria, such as having an income that falls within federal poverty guidelines or living in temporary housing.21

Although programs were paid for using federal funds intended to fund childcare for low-income families, there was a lot of flexibility in how localities and facilities interpreted requirements.22 This allowed centers to use their discretion and service families of various income levels, a groundbreaking precursor to universal childcare. However, regulations became more strictly enforced as federal funds decreased throughout the mid-1970s. Soon, such centers began to only serve children from low-income families, undoing efforts to create a more universal system of care in New York City.

Over the decade, ACD continued to work as the administrator for subsidized early care and Head Start for low-income families in New York City.23 In addition to regulating Head Start programs, ACD also administered vouchers that covered all or most of the cost of care in private settings.24

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

Constant Change: Early Education and Care in New York City from the 1980s–2010

President Ronald Reagan’s domestic policies—including significant cuts to social services budgets—coupled with a recession dramatically changed the landscape of homelessness in New York City. In 1981, the “Right to Shelter” was established for homeless individuals (Callahan v. Carey). Within two years, amid a sharp increase in family homelessness during which the city struggled to find places for families to stay, families won the Right to Shelter (McCain v. Koch, 1983). From January 1983 to December 1985, the number of families (adult families and families with children) in shelter rose from 1,500 to 4,000 families.25 By the mid-1980s, New York City began opening Tier II shelters, which were service-rich shelters providing such supports as job training and childcare to assist families in transitioning back to permanent housing.26,27 In the early 1980s, the United States Congress also gave states greater latitude to experiment with “welfare-to-work” requirements, foreshadowing massive changes to come in the late 1990s.28

1986–1990: Project Giant Step

In addition to dealing with the family homelessness crisis, Mayor Edward Koch’s administration was also focused on expanding early education across New York City. In the mid-1980s, ACD worked alongside the New York City Board of Education (BOE), the precursor to the New York City Department of Education (NYC DOE), to launch Project Giant Step. The program intended to provide a half-day program to all four-year-olds in New York City. Project Giant Step differed from the federal Head Start program in scope and practice. It focused on small class sizes and a robust set of staff, promising a teacher, teacher’s assistant, and a family aide in each classroom, the latter position focused on parental involvement.29 Project Giant Step staff attended monthly training sessions and had access to professional development.30 Further, the program aspired to be universal by providing programming to children from families of all income levels. While there was an emphasis on universality, it would be years before early childcare programs in New York City directly targeted families experiencing homelessness.

The collaboration between ACD and BOE to administer Project Giant Step could be considered groundbreaking for the time, as these two agencies were often politically at odds due to overlapping priorities.31 ACD officials saw BOE as better resourced and funded because while ACD had experience servicing children under five, they did not have access to the same organizational or physical infrastructures as the BOE. This tension, unfortunately, would be reproduced in each of their successor agencies, alongside each program innovation and change in mayoral administration over the decades.

Project Giant Step was initially conceived in response to the concerns of business owners and everyday New Yorkers before and during the Koch administration regarding the development of a future workforce and the socialization of the children of immigrant families.32 Programming was intended to set the basis for future learning and developing skills needed for a strong workforce.

Despite these successes, Project Giant Step faced issues currently seen in today’s early education landscape. In 1990, the year after Koch left office, the program only enrolled 6,850 students, just 17% of the total 40,000 children the program was designed to serve.33 Further, due to its half-day programming, many working families were left wanting for services that fit their schedules.

Additionally, as Project Giant Step programs were operated by either BOE or ACD, there were salary disparities that led to dissatisfaction among staff.34 Since BOE-operated classrooms had access to additional funding sources unavailable to ACD, preschool staff under BOE had significantly higher salaries than those at ACD. Discrepancies in pay made it difficult for ACD classrooms to retain qualified staff, an issue we continue to see today.

Efforts around Project Giant Step were quickly abandoned after the end of the Koch administration, starting with the closing of the Mayor’s Office of Early Childhood Education.35 Political tensions were not on the side of the program, as hostility and distrust between government staffers who remained from the Koch administration and those who entered under Mayor David Dinkins’s administration led to a lack of information-sharing about key initiatives like Project Giant Step. Many of the Dinkins hires were childhood education advocates who were once critical of the Koch administration. Additionally, it is perhaps the compulsory collaboration between two city agencies historically at odds that led to unsolvable hostilities that forced the abandonment of the initiative.

1990–200836:SuperStart

When Mayor David Dinkins entered office in 1990, the family shelter census had dropped to approximately 3,700 families (adult families and families with children).37 Dinkins had early success in moving families to permanent housing, but the recession’s lingering social and economic impacts drove more families into homelessness and shelter.38 Like President George H.W. Bush at the national level, Mayor Dinkins served just one term. Their successors, President William (Bill) Clinton, who entered the Oval Office in 1993, and Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, who entered office in 1994, presided over sweeping changes to public assistance, which would require an even deeper focus on access to childcare for low-income working families. Giuliani cut the City social services budget and tightened eligibility for shelter entry and public assistance. To comply with the Right to Shelter, he moved to quickly open “cluster sites.” While these units in apartment buildings provided families with the bare minimum of a roof over their heads and ensured that the City complied with the Right to Shelter, they lacked the social supports like childcare available in the Tier II facilities.39 At the federal level, in 1996, President Clinton signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA). In this act, the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) was replaced by Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), a time-limited benefit requiring recipients to be employed or engaged in work preparedness activities, presenting the need for additional childcare support for such families. 1996 also ushered in childcare changes at the city level. That year, the New York City Administration for Children’s Services (NYC ACS) was created as a standalone agency responsible for child welfare, Head Start, and other matters related to children and families. This removed HRA from direct oversight of childcare.40

With the end of Project Giant Step, classrooms that BOE had operated were worked into a new program for four-year-olds called SuperStart.41 The remaining classrooms run by ACD were added to existing Head Start and other childcare programs. While Project Giant Step initially targeted children from low-income families and then sought to expand to children of all income levels, SuperStart followed the more established approach of exclusively targeting low-income families.

Though SuperStart managed to withstand multiple administrations, it seemingly did not work to build upon the known shortcomings of its predecessors, such as program hours that did not fit an average parent’s work schedule, as it continued to primarily provide half-day care.42 The reason why program hours remained primarily half-day is unclear in historical documents.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg entered City Hall in 2002, following 9/11 and a related recession. With over 6,900 families (adult families and families with children) in shelter in January 2002, family homelessness was at record levels at the beginning of his administration.43 By the time Bloomberg exited office, the total number of families (adult families and families with children) had risen to over 12,600, new record levels in the aftermath of the Great Recession and the irreconcilable differences with New York State leaders over housing voucher policy. Bloomberg launched a zip-code based homelessness prevention program (Homebase) and tried several different approaches to moving families to permanent housing, but was stymied by New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s funding cuts to the Advantage housing voucher.44 During his three terms in office, Bloomberg revolutionized education in NYC in many ways.45 He successfully lobbied for mayoral control of the schools and focused on breaking up large high schools and creating many smaller thematic schools that could, he and his team posited, better prepare students for college and careers.46 Bloomberg’s first two terms overlapped with President George W. Bush’s terms in office and the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB), which had the goal of improving performance across the educational spectrum, particularly for students living in high-need communities.47

According to federal education law, a high-need community serves a population where at least 10,000 or 20% of enrolled students come from low-income families.

See: 20 USC § 1021(10)

As part of NCLB, President Bush launched the Early Reading First program, which, among other objectives, focused on providing teachers in Head Start programs and Title I preschools (schools receiving federal funds due to their large percentage of students from low-income families) with professional development for reading and literacy instruction. Such training would then help educators instill in their students the skills needed to learn to read in kindergarten.48 Funding was focused on increasing the quality of early education programs according to quality-rating systems, first developed in the 1990s, concentrating on continuous improvement to ensure programs exceeded baseline regulations.49 Standards were then formally defined at the federal level in NCLB, with initiatives such as Good Start, Grow Smart that required states to develop “quality criteria” for early education closely aligned to K-12 standards.50

From 2002 to 2012, enrollment in universal pre-K in New York City increased by 18,200, and 4,000 full-day seats were added in high-need districts. Despite all these efforts, the late 2000s and early 2010s also saw the subsidized childcare system shrink, with ACD, now under NYC ACS, cutting capacity as the City funds were cut and federal funds remained stagnant.51

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

Efforts to Standardize Care: Early Education and Care in New York City from the 2010s–present

2010–present: EarlyLearn NYC

In October 2012, as Bloomberg’s final year in office loomed, New York City began providing subsidized childcare and education under a new initiative called EarlyLearn NYC (EarlyLearn).52 This came about after several years of effort by NYC ACS, primarily at Bloomberg’s direction as part of his antipoverty policies.53 EarlyLearn was intended to be a redesign of the early education and childcare structure in New York City, standardizing a system composed of Head Start and childcare programs operated by nonprofit and community-based contractors with the primary goal of improving the quality of care for children with the greatest need.54,55

EarlyLearn provided contracts to homeless services providers to serve children five years old and younger.56 It also required centers to facilitate the formation of Parent Action Committees (PACs) that would encourage families to take an active role in their children’s education and attend workshops on child development and health.

Unfortunately, the transition to EarlyLearn was complicated by funding and implementation issues, some outside the City’s control.57 For one, the federal government implemented another round of Head Start funding, allowing private providers to compete with the City for these slots. This meant that many Head Start slots formerly administered by NYC ACS were now shifted to private providers. Families retained access to care, but it was no longer directly provided by the City. Enrollment in contracted childcare centers decreased during the EarlyLearn transition due to reduced capacity across the system and the implementation of new contracts between the City and different providers, disrupting longstanding relationships many former providers had.58 The number of NYC ACS vouchers was not impacted by this initial transition. While beginning to compile various childcare options into a unified network with more closely aligned standards, EarlyLearn NYC was seemingly a victim of unintended consequences and unforeseeable issues in its early years.

2014–present: Pre-K and 3-K for All

When Mayor Bill de Blasio took office in 2014, family homelessness was the highest it had ever been, with 12,700 families (adult families and families with children) in shelter.59 Yet, it would climb even higher, peaking at 15,899 families in 2016 before starting to tumble and plummeting in the last two years of his second term alongside the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2015, NCLB was reauthorized by President Barack Obama as the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). ESSA emphasized early learning, expanded access to pre-K, and refined quality criteria facilitated through Preschool Development Grant funding to assist states in developing high-quality programs for low-income children.60,61 ESSA also included important new provisions around preschool children experiencing homelessness. Critically, ESSA required that McKinney-Vento homeless liaisons ensure access to Head Start, Early Head Start, locally administered preschool programs, and early intervention services for homeless families.62 This shift sought to include early education in all discussions around providing educational access and opportunities for students experiencing homelessness at all ages, and it also highlighted the need for more data about young children experiencing homelessness with their families.

Under de Blasio, pre-K was massively expanded in 2014 into Pre-K for All, with the goal of providing high-quality services to over 51,000 four-year-olds in its first year.63 From Fiscal Year 2014 to Fiscal Year 2015, enrollment increased by almost 34,000 four-year-olds and an additional 15,000 in Fiscal Year 2016, peaking at nearly 70,000 in Fiscal Year 2017.64 Emphasizing the program’s universality, Pre-K for All not only promises admission for children from families of all income levels but also guarantees a seat for every four-year-old in the city.65

Pre-K for All was de Blasio’s signature policy during his mayoral campaign and subsequent tenure. In fact, its roots can be traced to his earlier city government career in positions such as New York City Public Advocate, when his office released a report on the unmet need for free early education and care in the city.66 As mayor, he continued to build upon his early education efforts in 2017 when he announced 3-K for All. During the announcement about the program, the mayor’s office referred to 3-K for All as “the most ambitious effort in U.S. history to provide universal … early childhood education for every three-year-old child regardless of family income.”67

Offering 11,000 seats for three-year-olds across the city, 3-K was built upon the pre-K model as an investment in early education and a means of alleviating the burden working families face when accessing and affording childcare.

Like predecessors Koch and Lindsay, de Blasio centered his early education initiatives around the idea that free, school-day education and childcare should be accessible to all New Yorkers and standardized in quality to serve kids across socioeconomic statuses equitably. Both 3-K and Pre-K for All are designed to help children develop socio-emotional skills, pre-reading and writing skills, early math skills, and physical strength and coordination skills.75

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

Transitioning Early Education and Care Programs from the NYC Administration for Children’s Services to the NYC Department of Education

In 2017, when announcing the expansion of early education to three-year-olds across New York City, the de Blasio administration also announced that early education programs then managed by the New York City Administration for Children’s Services (NYC ACS) would shift to management by the NYC Department of Education (NYC DOE).76 With the participation of related agencies, the administration transitioned oversight to consolidate program management, implement consistent standards and curricula, streamline contracting for independent providers, and integrate data collection.77

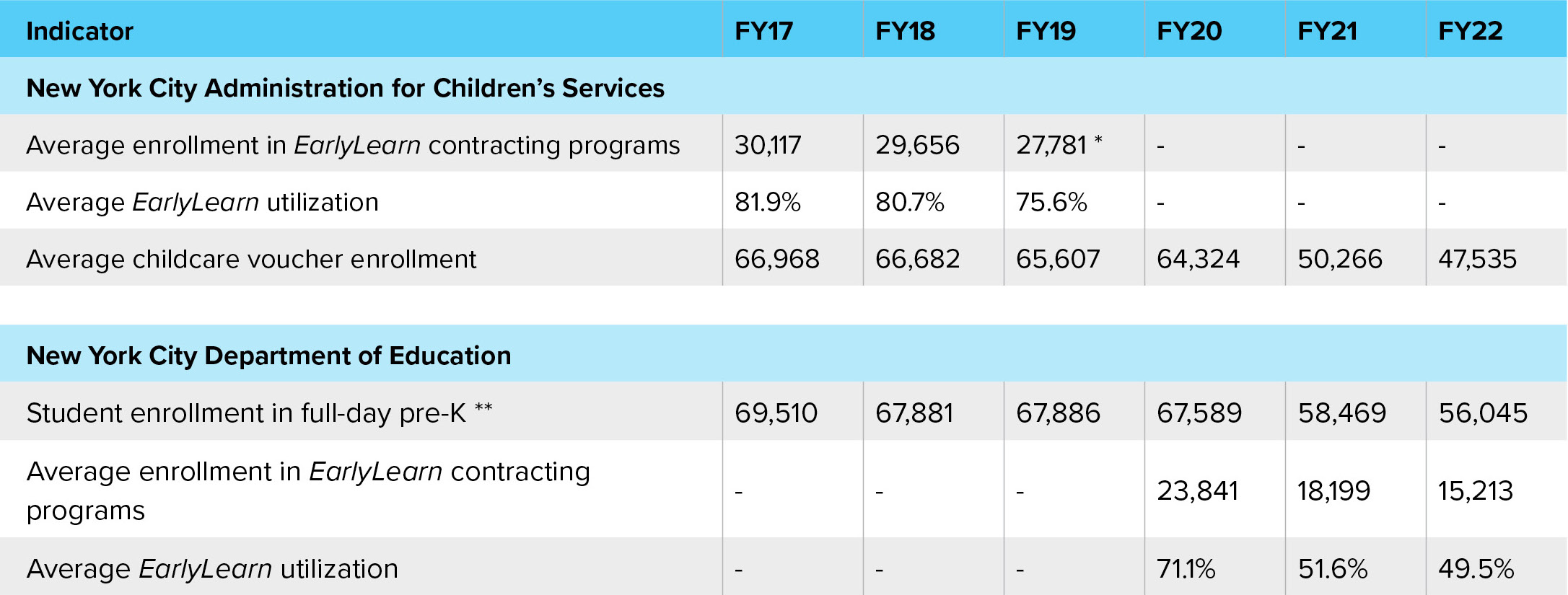

The increased availability of 3-K and pre-K seats through the expansion of 3-K and Pre-K for All led to higher enrollment in these programs and lower enrollment in EarlyLearn NYC, as families of three- and four-year-olds had expanded options. However, it is notable that after increasing enrollment numbers in full-day pre-K, from 15,917 in Fiscal Year 2014 to a peak of 69,510 in Fiscal Year 2017, enrollment in pre-K started to gradually decrease and continues to do so today.78 Another number that fell between Fiscal Year 2017 and Fiscal Year 2022 was the average childcare voucher enrollment. That number is composed of “mandated vouchers” tied to families with open public assistance cases and “other eligible children” voucher enrollment. The number of mandated vouchers fell as the number of public assistance cases dropped, and the number of children eligible for other reasons rose as the state expanded eligibility by income threshold. The average mandated voucher number rose for the first time in 10 years in the first four months of Fiscal Year 2023.79 Cash assistance applications also rose in Fiscal Year 2022 and continued to climb in the first four months of Fiscal Year 2023.80 We do not know what share of the families among the mandated voucher holders are living in DHS shelter, but given the size of the DHS families with children census, it is likely a significant share. Likewise, we do not know what percentage of families living in DHS shelter have not received a voucher either because they have not applied or because they do not qualify based on their immigration status or other factors.

Table 1: Performance Indicators During the Transition from Administration for Children’s Services to Department of Education

Source: Mayor’s Management Reports, 2017–2022.

*FY19 was the last year EarlyLearn NYC figures were reported under NYC ACS, as its administration transitioned to NYC DOE.

** Student enrollment numbers are reported by schools based on enrollment on the first Wednesday in October of the school year, known as Basic Educational Data System (BEDS) day.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

Today’s Early Education and Care System

Mechanics of Early Education Under the New York City Department of Education

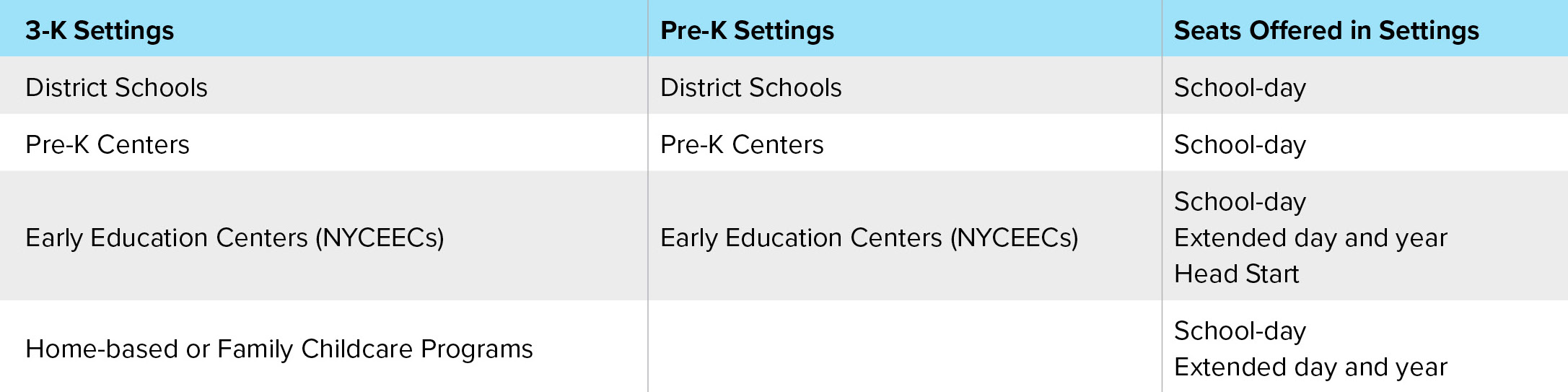

Early education is provided in various settings in the community and overseen by NYC DOE. Settings are intended to be placed in the community to ensure families have convenient options.81 Early education for three-year-olds (3-K) is offered in four types of settings: district schools, pre-K centers, New York City Early Education Centers (NYCEECs), and home-based or family childcare programs. For four-year-olds, pre-K is offered in all the settings noted above, except for home-based or family childcare programs.

District schools are run by the NYC DOE and situated in public school buildings, thus sharing the space with an elementary school. The NYC DOE also runs pre-K centers, but their locations only offer pre-K grades.82

NYCEECs are run and staffed by community-based organizations independent from the NYC DOE. These community-based locations are operated by several types of groups, such as faith-based organizations and nonprofits, including family shelter providers. NYCEECs are by far the City’s largest early education providers, with around 1,150 early education centers out of the approximately 1,800 pre-K and 3-K programs, continuing the trend of community-based groups being fundamental in the city’s work to provide children with education and care.83 Due to their place in the community, NYCEECs uniquely prioritize and serve students of families receiving services at the organization and students who speak the language in which the center specializes. They also have positions available to educators who do and those who do not yet have a New York State teaching certificate, creating a more diverse staff pool of members with different educational backgrounds as compared to NYC DOE teachers. Teachers at NYCEECs are notably not employed by the NYC DOE but by the early education center itself, differentiating themselves from employees at NYC DOE district schools and pre-K centers, who receive salary and benefits provided by the department.

Early education program placements are broken down into types of “seats,” differentiated by the schedule offered to families and their children. School day seats run programming during the daytime for 6 hours and 20 minutes during the school year— typically 8 am to 2:20 pm from early September through June. These hours are offered in all settings listed above. Programs that provide extended day and year seats and Head Start-funded seats run for up to 10 hours daily throughout the calendar year. Extended day and year seats are only offered in NYCEECs and family childcare programs, while Head Start-funded seats are only offered at NYCEECs.

Importantly, since the NYC DOE uses Federal Child Care Block Grant funds to provide extended day seats, the enrolled child must be a United States citizen or have some other form of legal residency. Parents do not need to have this status.84 Even before the influx of asylum seekers that began in 2022, it is possible that children have been excluded from extended day seats due to their immigration status or misunderstanding of how a parent’s immigration status affects their child’s program eligibility.

NYC DOE promotes its standards in these various early education settings by providing extensive program oversight.85 According to the NYC DOE, teachers employed at independent sites receive the “same professional development and support from the NYC DOE Division of Early Childhood Education as DOE teachers.”86 Keeping in line with de Blasio’s original vision of promoting equity across the city, standardized training opportunities for teachers would help ensure a student can receive a high-quality education in any of the various 3-K and pre-K settings. Sites also receive regular visits from inspectors from the City’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH), Fire Department (FDNY), and Department of Buildings (DOB) to ensure centers comply with health and safety mandates. Programs operating within shelter facilities also receive visits from the Department of Homeless Services (DHS).

Table 2: 3-K and Pre-K Settings and Seats as Offered by the Department of Education

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

Enrollment Process

The application for pre-K and 3-K under the NYC DOE attempts to streamline the process using its online portal, MySchools. It serves as a hub for researching programs, completing and submitting applications, reviewing offers, and checking waitlists.87 NYC DOE also offers “offline” options through its hotline and in Family Welcome Centers. The MySchools website and phone methods connect families to applications in many languages commonly spoken in New York City, with the hotline having the most comprehensive selection.

For all early education options, families are encouraged to begin enrollment by researching and exploring programs that fit their needs and doing so as early as they can—considering factors like ages served, location and transportation, languages spoken, and activities offered, among other features.88 Once applications are open, typically in late January (dates differ for 3-K and pre-K), parents must rank programs they are interested in by order of preference, allotting up to 12 choices. Applications must be submitted by their due date about two months later, after which they are reviewed based on priorities specific to each type of setting.

Families who have applied for or receive cash assistance and are looking to qualify for an extended day or year seat must apply through HRA Benefits Access Centers (HRA BACs, formerly known as HRA Job Sites).89 In these instances, HRA instead of NYC DOE determines a family’s eligibility for subsidized childcare. If they are deemed ineligible, a family must apply and use an ACS voucher to cover the cost of afterschool daycare.

Mid-Year Enrollment

Families enter homelessness throughout the year and may likely seek early childcare seats outside the regular enrollment season when they move to a shelter in a new neighborhood. Mid-year enrollment in 3-K and pre-K is possible at programs with extended day and year seats and Head Start seats.90 The NYC DOE directs families seeking enrollment during the year to visit MySchools. Here, families should explore the programs listed to find one with extended day and year seats, as these programs can enroll eligible children at any point in the year. Interested families are instructed to reach out to programs directly when looking to enroll mid-year for a Head Start seat or immediate accommodations with extended day and year seats.

The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act aims to make the enrollment process as accessible as possible to families experiencing homelessness. Eligible three- and four-year-olds have a right to immediate enrollment if the program they seek to enter has open seats. Such families cannot be denied enrollment into an available program due to missing any documents typically required in the process, although they are required to provide documentation at some point during the year.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

Early Education for Children Experiencing Homelessness

Importance of Early Education and Care for Children Experiencing Homelessness

Conversations around the efficacy of early education programs repeatedly arise as the landscape of early education and childcare in New York City continues to shift. Universally available early education, like Pre-K for All, may be valuable in promoting equitable education outcomes among children of different economic conditions. Research suggests that students show improvements in test scores when they attend early education programs with children from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds.91 When education programs are designed to be used by all and not just targeted to those “most in need,” students from lower-income families fare better than they would have in a program targeting their specific demographic.

Practicality of Early Education and Care Programs for Families Experiencing Homelessness

Throughout the history of the early education and childcare options in New York City, a common point arises on just how practical programming was and is for low-income families, especially families in shelter. Programs like SuperStart, EarlyLearn NYC, and others conceived explicitly to serve those considered most “vulnerable” often only offered half-day programming, leaving several hours during the day when working families would need to make other accommodations for their children.

Even programs that may be considered more forward-looking or those that offer full school-day programming can be impractical for working homeless parents. A school day schedule of 8am to 2:20 pm may be insufficient to cover traditional working hours, especially when considering homeless families, who may have work requirements to qualify for public assistance or housing subsidies and have limited, if any, access to family-based or private childcare. While the school day could possibly provide enough coverage for the required minimum number of hours of work activities families in shelter must meet to receive benefits, factors such as commuting times, work shifts that do not coincide with the school day, or unpredictable scheduling can leave many families in shelter in need of an extended day childcare option, whether it be in the same location as the child’s educational program or in another location. This is especially crucial to note as the jobs commonly held by shelter residents impose the abovementioned limitations.92

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

Facing Uncertainty: Funding Issues and Budget Cut Implications for NYC Families and Families Experiencing Homelessness

The de Blasio administration put much focus on expanding free early education for all children, beginning with pre-K, and then extending the initiative to include seats for 3-K in select districts. Perhaps his administration’s most significant achievement, de Blasio went further by announcing plans to expand free 3-K to all three-year-olds in New York City by 2023, promised in the Fiscal Year 2022 budget.93,94 However, as these plans were tied to a budget that would be partially implemented by a new mayoral administration and time-limited federal funds attached to pandemic relief, such an expansion could not truly be promised.

Enrollment Issues and Cuts

Throughout the United States, public and subsidized early education is often cut from state and city budgets during financial crises, such as the “Great Recession” of the late 2000s.95 Whether following this economic trend or reflecting his administration’s funding priorities, Mayor Eric Adams’s announcement of a pause in the expansion of 3-K for All has been met with substantial criticism from early education advocates, providers, and members of Adams’s own party.96In the 2022–2023 school year, the 3-K program had around 38,000 students enrolled in approximately 55,000 seats available for 3-K across the city, meaning 31% of seats went unused.97 While rationalizing the halt due to low enrollment numbers and the need to avoid a budget deficit, the City is currently working with a consulting firm to reevaluate where seats are located and redistribute them according to where the need is currently unmet. This study is anticipated to be completed before the beginning of the 2023–2024 school year, though no definitive date has been provided.98

Adding to the issue of under-enrollment is the limited number of seats most convenient for working families living in shelter. As mentioned previously, school-day seats at 3-K and pre-K programs are often insufficient coverage for working families and their schedules. While extended day and year seats exist for 3-K and pre-K, expansion efforts have prioritized school-day seats.99 This widens the gap between supply and enrollment, as school-day seats can go unused in areas that greatly need access to free, quality early education and care. Fortunately, some New York City officials have noticed this need. City Council members have laid forth an advocate-informed plan to shift the allocation of extended day and year seats and increase outreach to areas with the greatest need.100 However, it remains to be seen if and how these recommendations will be incorporated into lasting changes to the 3-K and pre-K system in New York City.

Early education programs in non-DOE sites also face the challenge of pay disparity seen in other early education and care initiatives in the past 50 years. Teachers employed at NYC DOE sites often have higher baseline salaries than their equally qualified counterparts in programs at NYCEECs. Just as seen in Project Giant Step, in which ACD teachers were paid less than those employed by the BOE, pay disparities make it difficult to retain staff. Pay disparity further exacerbates enrollment issues, as programs that are unable to hold onto their experienced staff can be forced to shut down or significantly reduce their offerings to the community, thus removing seats from the system and leading individual families to decide to take their child elsewhere or entirely remove them from the early education and care system.

Transparency

There is a lack of transparency around the application and enrollment process for early education programs, which is surprising as NYC DOE uses the same enrollment system, MySchools, for middle and high school admissions. The admissions guides show the total seats available and how many students applied for those in the prior year.101 However, no such numbers are readily available for 3-K or pre-K admissions. Instead, the website offers a vague explanation of acceptance chances by priority group (i.e., Zoned students: All received offers; Applicants living in the district: Some received offers; Applicants residing outside the district: None received offers). While this data may not be available for newly opened 3-K programs, it should certainly be available for pre-K programs, and parents should have access to it. These numbers are particularly critical for applicants to extended day programs so they can get a sense of the likelihood of being accepted to programs or whether they will have to pair a school day seat with a childcare voucher elsewhere. In early May 2023, an NYC DOE spokesperson stated that during School Year 2022–2023, there were 11,000 unfilled extended day and year seats.102 However, little is accessible in determining where those seats were located. Using MySchools more effectively to let families know exactly where those openings are and make it easier to slot their children into them quickly is critical.

It remains to be seen what recommendations will come of the 3-K seat reallocation study solicited by the Adams administration, though they are expected before the beginning of the 2023–2024 school year. City Council members have been calling for changes to the enrollment process, allowing families to enroll directly with providers on-site. Council members are also calling for ways to make extended-day, year-round seats available regardless of income and for funding to increase salaries for community-based program staff in line with their NYC DOE classroom counterparts.103,104 Such recommendations, if implemented, can help early education and care programs better serve families and further ensure the early education system in New York City is accessible to families experiencing homelessness.

Data Collection and Reporting

Fall 2023 marks a watershed moment when the children born in 2020, the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, become eligible to enter 3-K and the public education system for the first time. The City would be wise to track what share of the overall population of three-year-olds enters 3-K programs— with particular attention paid to trends among families whose 3-K eligible child is an only or eldest child and therefore the adults have no prior parental experience with the system. That data should be disaggregated by living situation where that information is available to better understand the needs of families experiencing homelessness, including those living in shelter. Such a task should be relatively feasible for the City, as it already surveys entering kindergarteners on whether they used universal pre-K and, if not, asks why.105

Among the potential reasons families can select for why they did not enroll their children in free pre-K are: they did not know about free pre-K, the available programs were half-day, but the family needed full-day, or conversely, the available options were full-day, but the family needed half-day, the parent wanted to keep the child at home, the parent wanted to keep their child in the same educational setting as the year before pre-K, the parent had “concerns about the quality of NYC DOE-funded pre-K available to me,”or pre-K was not available at the family’s zoned District school.

Source: New York City Department of Education Office of Early Childhood. (2021). New Kindergarten Admit Questionnaire.

Once collected, this information should again be run against student living accommodations to better understand the choices families living in shelters make and how these choices may differ compared to housed families. It is also expected that large numbers of asylum-seeking families will continue to arrive in NYC throughout 2023 and enroll in public schools, including early education classrooms. These factors will likely converge in data points that could indicate growing long-term trends. At this time of change, it is critical to more closely track and make publicly available information about Students in Temporary Housing among 3-K and pre-K students so additional school-and shelter-based supports can be made available for them and their families.

Disaggregated data would also help track the utilization of NYC ACS childcare vouchers by families experiencing homelessness. While the City tracks utilization by New Yorkers as a whole, seeing what trends exist depending on living conditions could help inform outreach efforts. It could particularly help see if improvements could be made to encourage families experiencing homelessness to sign up for childcare so they may be able to better seek stable housing. Publicly reporting this enrollment and utilization information could be as simple as reporting it in the yearly Mayor’s Management Report, allowing a more holistic look at where the outreach efforts of local elected officials and advocates stand.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

Conclusion

The early education and care system in New York City has been hindered by well-intentioned policies that have fallen short in meeting the needs of families experiencing homelessness, as well as by challenges that have seemingly recurred throughout the system’s history. Since the 1980s, New York City mayoral administrations have teetered back and forth between early education and care policies that targeted children based on government-defined perceptions of need or more expansive programs hoping to provide access to all children of a certain age. Additional efforts have been made to consolidate offerings under EarlyLearn NYC and migrate enrollment processes onto an online platform in an attempt to improve services. Still, issues remain for families and for service providers. Limitations on the availability of data and transparency regarding seats have further made it a system that is not currently working for families who most need free and accessible childcare, such as those experiencing homelessness.

The current issues in New York City’s early education system place homeless families at risk of missing out on free education and care for their children. These childcare services are not only crucial in helping these families gain the stability necessary to seek permanent housing but also provide an education that will help ensure homeless children do not developmentally fall behind their stably housed peers.

However, it does not have to be this way. There is an opportunity to avoid cyclical changes and instead transform the system into one that meets the needs of families. In addition to calls by childhood education advocates to expand extended day and year seats, local officials have the opportunity to streamline enrollment processes, which can prove burdensome for all families, but specifically for those experiencing homelessness. Fewer hurdles to jump can translate into better utilization of all available seats. Partnering this change with increased data reporting to aid in decision-making by parents could truly equalize the playing field for children in shelter at the start of their educational journeys. In doing so, early education and care in New York City can continue advancing toward universality.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

The writing and research for this report was conducted through June 2023.

For additional copies or inquiries: Email INFO@ICPHusa.org or MEDIA@ICPHusa.org.