Publisher’s Note

Dear Reader,

For several years now, UNCENSORED magazine has highlighted programs that aim to alleviate family poverty and homelessness, primarily through efforts in the areas of employment, education, and housing. However, in our Fall 2014 issue, we are excited to have education, for both children and adults, serve as the single unifying theme.

The articles focusing on children include our feature on the New York City–based Writopia Lab, a national community of creative writers who work to foster literacy and develop critical-thinking skills in children and teens of all backgrounds. A representative of the Homeless Children’s Education Fund, based in Pittsburgh, has contributed this issue’s article on the organization’s innovative “Conscious Caring” curriculum, created to teach elementary school students about the plight of people—often children—who face homelessness. One person with firsthand experience in that realm is Nikki Johnson-Huston, who is currently a highly successful tax lawyer in Philadelphia—but was once a homeless nine-year-old in California who had little to call her own except her dreams for a better life. Nikki has written a candid, moving remembrance of her ordeal and how it has affected her. Based on her own trials, she stresses the need to instill a sense of possibility in poor and homeless children, as part of their overall education. For those of us in either the policy or program community, the final article is a reminder that learning is a lifelong process. The Massachusetts-based COMPASS Community Collaborative provides a poignant example of how giving homeless adults the education and job skills they need to live independent lives helps them provide for their families in the long run.

With the latest statistics showing that there are now nearly 1.3 million homeless students in the United States, focusing on education is more important than ever. We look forward to hearing your thoughts on this issue.

Sincerely,

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, Publisher

President and CEO, Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The Write Stuff:

The Power of Expression in a Safe Space

by Katie Linek

In a small New York City theater one May evening, the lights go down and a series of short, entertaining, and thought-provoking plays begins. Touching on themes like cultural tension, mental illness, and dysfunctional relationships, each play brings something unique to the table. What’s more, each play was written by an up-and-coming playwright under the age of 18.

The writers are all students of Writopia Lab, a nonprofit that holds writing workshops in schools, treatment facilities, homeless shelters, and public libraries. The organization, which operates in several cities, works with children and teens from all walks of life, aiming to foster joy, literacy, and critical thinking through creative writing.

Writopia students write anything from fiction and memoirs to graphic novels and poetry. The annual Worldwide Plays Festival highlights the work of the program’s young playwrights.

A Playwright Is Born

Writopia Lab produces the weeklong festival each May, presenting the plays Off-Broadway, in a professional New York City theater that is smaller than those traditionally used for Broadway shows. The event celebrates voices and themes that span socioeconomic groups and geographical regions, delivering humor and fresh perspectives. Each play is developed and polished by a young writer at one of Writopia’s workshops; professional directors and actors are then matched to each play, rehearsing the work and bringing it to life.

“The writing of our Writopia students continues to bring remarkable creativity, risk, truth, and beauty to the stage, while the professionalism and skill of the directors, designers, actors, and crew create a spectacular platform that showcases the power of these works,” says Kara Ayn Napolitano, managing artistic director of Writopia Lab.

Students in the Writopia workshop play a game in which they have to help their classmate guess the emotion written on their forehead by using synonyms and descriptions of the word.

Worldwide Pants, Inc., owned by television host and comedian David Letterman, has sponsored the festival for four years, enabling Writopia Lab to present the work of more than 250 playwrights. Forty-eight plays and musicals were produced this year alone.

Markus, an eighth-grader whose play was produced in May, drew on real-life experiences to develop his story. Raised in the Bronx and attending the free Writopia workshops offered by the New York Public Library (NYPL), he wanted to reflect New York City’s diversity while incorporating his love of classical music. The result was Premiere, a play depicting cultural tensions between two students—one Jewish, the other German—who are brought together by classical music.

“I really enjoy the program,” explains Markus. “I learned how to be a better writer and to elaborate more. I definitely want to continue writing.”

“Writopia was a wonderful experience for the children at the New York Public Library—offering them a creative outlet in a unique and innovative way,” says the NYPL’s director for library sites and services, Kevin Winkler. “The library strives to offer a variety of programs that can inspire as well as educate, and Writopia allowed us to do just that.”

Another Writopia student, Sharm, explains that Writopia helped him get his emotions out, “because you can be creative and open there.” Sharm joined the program while living at a treatment facility for incarcerated youth. His play, Housing, mixes equal parts humor and reality in exploring a young man’s relationships with his sister and his girlfriend as they argue over living arrangements.

Expressing Emotion through Writing

Students find themselves at Writopia Lab for an assortment of reasons; some are already accomplished writers in search of high-quality feedback, while others are struggling with writing in school and need a safe place to develop their skills. Still others turn to Writopia as an alternative form of therapy.

One young writer, Ronnie, lives in a treatment facility that provides long-term care to teenagers with behavioral problems, emotional difficulties, and mental illness. Most of the teens residing there have been through the juvenile justice system, including Ronnie.

A group of students listen to each other’s work and give constructive feedback with the help of a Writopia instructor.

Upon joining a Writopia Lab workshop, Ronnie found a comfortable and productive way to explore and express his anger and depression—through his writing.

“I love writing poems,” explains Ronnie. “If I had a rough week, I can come down to workshop and sum it all up in a poem. It helps a lot.”

The program coordinators describe him as passionate, prolific, and engaged. Ronnie says that the workshop is the highlight of his week and plans to continue participating in Writopia after he leaves the residential treatment facility.

“The activities we have in the residential treatment facilities are used for nontraditional therapy,” says Fastima Gooden, activity coordinator at one of the facilities where Writopia offers workshops. “These defiant kids come to Writopia and are given the opportunity to openly express themselves. It really boosts their self-esteem.”

In May, Voices, a play written by Ronnie about a young man’s struggle with mental illness, was produced.

Creative Writing for All

In 2006 Writopia’s founder, Rebecca Wallace-Segall, was hired by the principal of a school on Manhattan’s Upper West Side to run a creative writing program.

“I loved what I was doing there, and the kids were getting a wonderful experience. They were winning more writing awards than those from the top private and public schools,” explains Wallace-Segall.

In 2007, when it was announced that, despite its success, the writing program was going to be cut, Wallace-Segall and ten parents decided to found Writopia, taking the creative writing program to the public sector.

“My original work at the school was with kids who came from privilege, and when we started Writopia, we wanted our workshops to be available to a broad range of kids,” Wallace-Segall says. “We are the most socio-economically diverse writing program in New York City. We’re not a segregated program; we dig deep into diverse characters and people, and by exposing them to each other, their lives and writing become richer.”

Although founded in New York City, Writopia has spread to areas across the country, including Westchester County, New York; Los Angeles; Washington, D.C.; and Chicago. The program now serves more than 2,000 kids per year and continues to grow.

Enrichment for a Vulnerable Population

One hot Tuesday in August, around 15 kids are seated in a classroom at Saratoga Family Inn, a homeless shelter run by Homes for the Homeless, a New York City–based shelter provider. Hanging on the wall are signs that read, “Attitude is a little thing that makes a big difference.” The room is buzzing with energy and excitement as the children talk.

This is the last week of a six-week workshop run by Writopia as part of the Saratoga Summer Day Camp, a full-day program for homeless and at-risk youth. Meeting three times a week, the instructors help two groups of kids—one made up of children under 13 and the other made up of teens—develop short stories from which they will read excerpts for an audience in just two days. In September, they will each receive a book of all of their stories.

One student reads her latest short story aloud while another listens closely, taking notes to share her comments with the writer once she has finished reading.

A handful of the younger kids are at the computers off to the side of the room, finishing and editing their stories with the help of instructors who walk around offering guidance and asking thought-provoking questions. Across the room, kids who have already finished take part in games and exercises to keep their creativity flowing.

One ten-year-old girl sits at a table surrounded by her peers, answering their questions from the perspective of Chrissie, a character she created. Her answers get her thinking about what to include in her short story to develop her character further.

In another activity, students use the five senses to describe where they are from. One girl who has been quiet up until now brightens up and offers to read her poem, beginning: “In my Africa, we dance.” The instructors’ faces light up, and the other children actively listen. When the poem is over, the other members of the group take turns giving positive feedback. The young girl, who seemed down at the start of the day, now appears engaged and excited to continue working on her poem.

Elsewhere in the room, an eight-year-old boy sits alone, looking upset. One of the instructors walks over and takes a seat next to him, asking if he is all right. When he does not respond, the instructor asks if writing another story would make him feel better. The boy nods his head, gives a little smile, and runs back over to a computer.

Later in the day, the teen group gathers in a circle in a small room. This group is initially withdrawn, but as they go around the circle sharing their favorite and least favorite words, the mood lightens. Some students break away to finish their stories, while others share with the group parts of what they have written. Each time, they are flooded with positive feedback from their peers, which visibly increases their confidence.

The instructor, Jessie, reveals that seeing this change in attitude is her favorite part of the job. “You can see it. These kids come in, some visibly in a bad mood. It’s rewarding to see that by the end they are participating and engaging with the group. They are all so talented.”

Homeless children are more likely to struggle in school and have emotional and behavioral issues than children living in stable housing. Writopia helps these kids express their emotions through writing while improving their skills.

“Writopia instructors work with our kids one on one, giving them personal attention and showing them that writing can be fun,” explains Saratoga Family Inn Administrator Mike Fahy. “Homes for the Homeless knows how important it is for all kids to have the same opportunities to learn and grow. That’s why enriching activities like Writopia, which works with children from all walks of life, are so important and appreciated.”

The Writing Crisis

According to research, students of all ages struggle to write proficiently. Data from the National Center for Educational Statistics and the National Center for Educational Progress found that only one in five students in the U.S. is able to write competently. The English Journal, published by the National Council of Teachers of English, reported that 67 percent of high school freshmen tested below grade level in writing.

Theories about why this may be the case run the gamut. Some believe the issue is that writing instruction is not rigorous enough and focuses too much on expressing feelings, rather than on teaching students how to write logically and precisely. The new Common Core Standards, national guidelines adopted by 45 states and the District of Columbia, address that concern by putting emphasis on persuasive writing.

Actors perform in Premiere, a play written by Writopia student Markus. Markus was inspired to write about cultural tensions by the diversity of his own school, and incorporated his love of classical music into the play.

Others, however, argue that standardized testing and the associated curricula are the problem, leaving kids feeling disconnected from the learning process. Wallace-Segall explains, “Kids don’t feel like thinkers or creators anymore.” In fact, one of the top three reasons students give for their dislike of writing is that the constrictive nature of many assignments makes them feel out of touch with what they are doing, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Students also say they dislike writing because they do not know how to write or are not sure what teachers want.

Many times, students do not want to express themselves for fear of being laughed at by peers or causing concern among adults with their violent, mature, or “out-of-the-box” ideas. For example, a student writing a story about suicide is not necessarily suicidal. Writopia, on the other hand, is a place where unusual ideas are taken seriously and serious ideas do not cause alarm.

In 2012 Rebecca Wallace-Segall spoke at a TEDx event, a local, self-organized program that brings people together to spark deep discussion. TEDx events are hosted by TED, a global nonprofit dedicated to spreading ideas in the form of short, powerful talks. Wallace-Segall’s talk centered on education policy and the importance of empathetic, high-level creative writing instruction. Wallace-Segall explained, “When you start talking about grades, creativity often shuts down. A lot of teens say they don’t feel comfortable being their full selves in the classroom. This may lead to kids feeling disconnected, but sometimes it leads to depression. In the most extreme cases it leads to kids dropping out of school.”

For a key demographic served by Writopia, low-income and homeless students, mitigating the possibility of students’ dropping out of school is extremely important. The Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH) found in its report “A Tale of Two Students: Homelessness in New York City Public Schools” that after four years in high school, only 50 percent of homeless New York City students graduate on time, compared with 65 percent of all students; 15 percent of homeless students drop out.

ICPH explained in another report, “An Unstable Foundation: Factors that Impact Educational Attainment among Homeless Children,” that children who experience homelessness at a young age are more likely to demonstrate behavioral problems such as aggression, social withdrawal, depression, and anxiety, which can lead to academic, social, and economic difficulties. Writopia’s therapeutic effect on its students may help to offset some of the behavioral problems that can occur.

In addition, studies show that strong writing skills are essential in the professional arena, no matter the field. Over two-thirds of salaried jobs require a significant amount of written work. It is no surprise, then, that workers with good writing skills stand a much higher chance of advancing in their careers.

The Partnership for 21st Century Skills, surveying employers about the writing of recent graduates hired, found that 26 percent had substandard writing abilities and that 28 percent of those were so deficient in written-communication skills that they struggled with their basic duties. The National Commission on Writing estimated that top American companies spend over $3 billion a year, and state governments around $221 million per year, to foster employees’ writing skills.

The Key Is a Safe Space

The key to the program’s success is that the writing process takes place in an uncensored environment with the guidance of published authors and produced playwrights. At Writopia students find a creative and intellectual atmosphere that might not otherwise be available to them. For young people who struggle with verbal and written expression, the program offers a safe space to develop these skills. The students become comfortable with expressing themselves on paper, and many eventually acquire a love of writing.

“Writopia has grown so quickly because kids and teens need a safe place to be themselves … to think, process, write, and share their ideas, experiences, and fantasies,” says Wallace-Segall. “Writopia has grown because our instructors are the warmest, most brilliant people in their cities—and because they are deeply invested in the well-being of youth. We have complex, dynamic conversations with them about each and every sentence, story development, and resolution in their stories rather than assess what is ‘right’ or ‘wrong.’ This is something incredibly exciting for most kids and teens who are used to being ‘taught’ and ‘graded.’”

Writopia uses a student-centered approach to teach writing, allowing lessons to occur naturally in the course of the work. “Their work is generated from what the kids want to do and write, which leads to an authentic writing experience,” says Wallace-Segall. “These kids talk about and process the world together. They develop their pieces with, and in support of, one another. In the end, the pieces that emerge are extraordinary.” Students use tools and games to help start and share stories. Instructors then challenge students to set and achieve writing goals, encouraging them to complete at least one well-developed, polished piece over the course of the workshop.

“I love the moment when a writer is surprised by the power of his or her own work—when they discover they expressed something new and bold,” explains the associate director of camps and curriculum instructor for Writopia, Danielle Sheeler. “I love when a writer realizes that they have met their own goals and feel proud of their accomplishments.”

Writing is not the only skill improved at these workshops, however. Students learn effective verbal communication, editing, analysis, and leadership skills while working with their peers. The access they are given to technology gives the writers an opportunity to acquire computer skills necessary in today’s technologically driven workforce.

Writopia also does not turn anyone away for financial reasons. Fourteen percent of its program funding comes from donations or grants, such as David Letterman’s production company, Worldwide Pants. The other 86 percent of Writopia’s funding comes from its sliding-scale fees. Wallace-Segall explains, “There is a no-questions-asked, no-application, pay-what-you-can policy.”

“We Help Kids Find Their Voices”

Success stories flow out of Writopia Lab, with results both academic and emotional.

The Worldwide Plays Festival is just one of several programs offered by Writopia Lab. After-school and weekend workshops, a summer sleepaway camp, and help with college application essays are also offered. Some students have performed their poetry at the Nuyorican Poets Café, a famous New York City venue for poetry, hip-hop and other music, video, visual arts, comedy, and theater, which has a long tradition of providing performance opportunities for both rising and established artists.

Program participants have won numerous regional and national Scholastic Writing Awards, the nation’s most prestigious and longest-running writing competition for teens. Two Writopia participants won the National Gold Medal Portfolio Award, the highest Scholastic Art & Writing Awards honor, which includes a $10,000 scholarship.

Sharm, a Writopia student who joined the program while living at a treatment facility for incarcerated youth, receives a rose after watching his play performed on stage to much laughter and applause.

What’s more, reluctant kids and teens are now considering themselves writers, many of those who hated writing now love it, and kids who already loved to write are now doing so at a higher level and more openly than ever before.

Wallace-Segall tells the story of a young man who came to the program just last week. “A mother told me that her son, a teen who had previously declared that he had no interest in college, stated that he wanted to ‘become a writer and go to Yale.’ I loved that. He spent one week here and he felt better about himself as a thinker and an artist—and he felt a part of the world in such a positive way.”

“They become more confident about expressing their feelings, thoughts, and experiences on the page. They feel that their stories are important and worth writing down and sharing,” says Sheeler.

Wallace-Segall continues, “We help kids find their voices and intellectualism. We ask them to think about why characters do what they do. They think on deep, beautiful, philosophical levels. Parents tell us that we have reawakened their children’s spirit.”

Parents report seeing an increased confidence in writing, improved grades and standardized test scores, strengthened relationships with teachers and friends, and more informed and lucidly expressed views of the world.

The instructors also find the program rewarding, for the students as well as themselves. Strong connections form between the instructors and students. Sheeler explains, “The teens often write memoirs and autobiographical poetry. They open up and share many personal life experiences. We establish a strong sense of trust.”

Rebecca Wallace-Segall loves helping teens “calm down, open up, laugh, and write more and more honest, wonderful work. I cry almost every day here because that process can be so intense.”

To protect the safety and privacy of those we interviewed, we have not included the full names of program participants and treatment centers.

Resources

Writopia Lab, http://writopialab.org ■ New York Public Library, http://nypl.org ■ Homes for the Homeless, http://www.hfhnyc.org

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

On the Right Track:

COMPASS Coaches Homeless Parents on the Road to Employment

by Suzan Sherman

Earlier this year Ana Rodriguez, 25 years old and 31 weeks pregnant with her son, found herself in a homeless shelter with her 11-month-old daughter. She had been working as an assistant manager at a local retail-clothing chain in northeastern Massachusetts, a low-wage position that did not provide nearly enough money to pay her rent and other expenses. In a fit of frustration, she quit her job and began the merry-go-round of sleeping on various friends’ couches. “I just couldn’t support myself,” Ana says plainly. After a time, with nowhere else to go, she arrived at the Lawrence Department of Transitional Assistance, which promptly placed her in a family shelter in nearby Haverhill.

Family shelters most often serve single mothers, 90 percent of whom suffer from emotional and physical trauma, including but not limited to the effects of child abuse, domestic violence, rape, and homelessness itself. A majority of these mothers are without a high school degree; have never garnered a substantial income of their own; lack support, role models, and social networks; and struggle to support themselves and their families. Their work histories are often skimpy at best. Ana might have remained wholly dependent on state and federal assistance had it not been for her housing advocate at the shelter, who provided her with a flyer from COMPASS Community Collaborative—a job-training and placement program—and encouraged her to give them a call.

COMPASS, which has offices in Lawrence and Lexington, began in 2002 as a setting for expressive therapy, women’s groups, and parent-child play groups aimed at strengthening relationships within homeless families. Those at the organization eventually realized that their work, though beneficial, was more of a Band-Aid than part of a long-term solution for the growing family homelessness epidemic in Massachusetts. “While these activities provided a voice, stress reduction, and emotional support for families,” says Jodi Wilinsky Hill, COMPASS for Kids’ founder and executive director, “there were no measurable long-term impacts of our work. When families exited shelter, they were no better positioned to do better than they were when they entered shelter. With an acute affordable-housing shortage in Massachusetts and long, damaging shelter stays, we recognized that we wanted to do more about the multigenerational tragedy that is family homelessness. Access to education and jobs as the core of family economic development became our new focus—our mission.” In 2011 COMPASS scaled up its programming by launching a workforce component, with the knowledge that economic self-sufficiency is the key to stability and a brighter future. Recent statistics underscore the challenge the organization faces: in July 2014 there were 3,386 homeless families in the state living in emergency-assistance shelters and motels, a marked increase from three years before, when 2,651 families were documented as homeless.

Tiffany works behind the counter at Coffee Cann after completing the COMPASS program, taking a step towards financial independence.

Nonetheless, the still relatively new COMPASS Community Collaborative has achieved some impressive outcomes: over the past three years, it has enrolled 94 parents in nine cycles of its work-skills programming, with a 70 percent graduation rate. Fifty-two percent of graduates have been hired full-time by the companies that provided their paid internships through COMPASS. More than 80 percent of those hires still held their jobs after three months. Eighty percent of graduates have found employment after completing the COMPASS program, many of them in long-term positions.

After giving birth to her son, Ana took her housing advocate’s suggestion and contacted COMPASS. She spoke to the program manager in the Lawrence office, Leslie Kent, who encouraged her to attend one of their weekly information sessions. Past program graduates co-run these sessions along with COMPASS staff, so that prospective participants hear of their peers’ positive experiences firsthand. Participants are then encouraged to attend one-on-one intake sessions with COMPASS staff members, who gather information on their clients’ work and educational histories and potential career interests.

At her intake session, Ana signed on to have Leslie as her coach, to guide her through the program. COMPASS considers coaching—a blend of conventional life-coaching techniques with trauma-informed case management—to be at the heart of its work. Staff coaches work tirelessly and over the long term with participants as well as graduates. Between meetings, participants can access staff in person or by phone, text, or email, and staff members even make shelter visits when necessary to ensure participant success.

Based on clients’ individual work histories, education levels, and personal interests, coaches place them in one of five career tracks. They consist of the job-search-only track, for those few with strong work histories; a soft-skills “boot camp” and job-search track, which includes stress management as well as behavioral- and parenting-skills components; a paid on-the-job-training internship track, for participants who need to build their résumés; a personal-care-assistant track, for those interested in exploring the health care field; and a community-college track, in which child development and computer courses are offered at the local Northern Essex Community College and Cambridge College, along with the soft-skills and job-search components.

The COMPASS workforce program also assists families in developing financial literacy and learning to save money through 12-hour courses provided by Lawrence Community Works, the local community development organization. In addition, the organization helps with transportation to and from the workplace (which includes stopgap funding for public transportation, gas subsidies, and organized carpooling). COMPASS supports clients as they pursue educational goals (through GED classes, training in English for Speakers of Other Languages, or ESOL, and college enrollment). Finally, the group works to foster professional skills, such as writing successful cover letters, résumés, and thank-you notes as well as doing prep work that includes conducting mock job interviews, understanding work-appropriate clothing, and training in the importance of punctuality and conflict resolution.

“Since I was little, I had wanted to become a nurse,” Ana says, so it was a natural fit for her to enroll in COMPASS’s personal-care-assistance program. “The training was hard at first,” Ana admits. “Every day from 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. for eight weeks. I put my kids to bed at 6 p.m. and then did my homework afterward.”

After completing the COMPASS program, single mother Kimberly took an assistant teacher position at COMPASS partner Little Sprouts and a year later obtained an early childhood teaching position with a 40 percent increase in pay.

A few weeks after graduating from the program, Ana was hired as a part-time nursing assistant at Wingate Healthcare, a senior-living facility, and she is looking for supplemental work. With COMPASS’s encouragement, Ana opened her own bank account. She and her two children currently reside in housing subsidized by the state, where she pays 30 percent of the rent, but Ana hopes to save enough money to afford a market-rate apartment when the subsidy reaches its end, in two years. “I’m truly grateful to COMPASS,” Ana says. “I learned how to be presentable in going on job interviews and to send thank-you notes afterward. Without their help, I wouldn’t have been able to move forward.”

Like many formerly homeless adults, Ana has only a tenuous connection to her original family. The support and encouragement that she and others in the program desperately needed have come through her relationship with Leslie and other COMPASS staff members, among them Paul Fisher, the employment training specialist, and Marianne Pelletier, who co-founded COMPASS Community Collaborative and pinch-hits when needed as an instructor, program manager, coach, or resource advisor. COMPASS graduates have also been known to form makeshift extended families and look out for one another.

Hill is equally committed to connecting with the population she serves. “Everyone gets my personal cell phone number, and not one person has ever abused it,” she says.

Hill says that the COMPASS program could have never become the success that it is without its connection to Susan Leger Ferraro, the CEO of Little Sprouts, a local child care provider with multiple locations throughout the region. Ferraro, a single mom, began Little Sprouts when she was 17 and has grown her company from $15,000 to $18 million in annual revenue. Hill describes Ferraro fondly as a “creative problem-solver.” Hill first met Ferraro at the Little Sprouts in Lawrence in 2007, when she had hit a roadblock in developing the COMPASS Community Collaborative pilot program. At the time COMPASS was serving homeless single moms and their children living in congregate shelters in Waltham. “One of my program managers introduced me to Ferraro in an effort to solve an acute shortage of child care voucher slots for the children of the mothers we had hoped to have in our program,” Hill recalls. “At the time, we had funding from the Massachusetts Department of Transitional Assistance to serve 40 families, but none of the young children in these families were in early-childhood programs, and there was no voucher space near the shelters.”

Ferraro was able to provide 40 voucher slots at Little Sprouts to COMPASS children, a game-changer for Hill, who could now offer child care to mothers who would have otherwise never been able to attend the program. In addition, Ferraro began hiring COMPASS graduates for paid on-the-job training in early-education care, which in turn gave mothers much-needed work experience and provided them with references for other positions in the future. “This is about opening doors,” Ferraro says. “It’s been great collaborating with COMPASS, and they’ve been such an asset to our organization by making our team feel empowered in the process of helping to create better lives for young-adult parents trying to make their way in the world.”

Last fall, after completing the COMPASS early-education training and an internship at Little Sprouts, Yorian Vega, 31, was hired there as a part-time employee. She now works 40 hours a week as a teacher of toddlers. Although Little Sprouts does not provide her family’s medical insurance—Yorian has twin boys, age 10, and a 12-year-old son—she is able to receive care through MassHealth, a public insurance program for low- and medium-income Massachusetts residents. It was only a year ago, after being laid off from her job as a receptionist in a Spanish-language setting, that Yorian grew increasingly concerned that she would lose her market-rate apartment. Through HomeBase, a homelessness-prevention program in New England that offers financial assistance for those in need of funds for rent, utility bills, and other housing expenses, she was referred to COMPASS. Soon afterward, Leslie became Yorian’s coach.

Carmen obtained a job with GEM Shipping after graduating from COMPASS and is working hard to advance her career.

“I knew that I wanted to work with kids,” Yorian says, “but I was so concerned about my English.” When Yorian first arrived in Massachusetts two years before, after being told by doctors in her native Puerto Rico that one of her twins had a severe medical problem and might not walk in the future, she did not speak more than a few words of English. Knowing no one in Massachusetts except for a couple of cousins who lived in Lawrence, she made her way from San Juan to Shriners Hospital for Children, in Springfield, followed by Boston Children’s Hospital for the specialized medical treatment that her son would not have received in Puerto Rico. Her son’s prognosis improved considerably in Massachusetts, but Yorian still wasn’t speaking English. “I knew that I needed to try [to speak English] in order to get work, and Leslie kept telling me that I could do it.” Without any formal training in the language, she simply began learning and speaking it as well as she could, making great progress.

The Little Sprouts child care facility where Yorian works is a 20-minute walk from her apartment; thanks to her job, she has not had to move to a smaller market-rate apartment or seek shelter. At the end of the workday, she takes a taxi home to ensure that she is there when her kids return from school. “The program was amazing for bettering my life,” Yorian says. “And I still talk to Leslie all the time.”

Besides Little Sprouts, COMPASS also has job-placement relationships with Salvatore’s, a restaurant in Lawrence, which prepares participants for careers in the restaurant and customer-service industries, and Gemline, another Lawrence-based business, which offers manufacturing and screen-printing experience. Not coincidentally, Ferraro is on the corporate board of Gemline, a longtime friend of COMPASS. Other relationships with local businesses are in the works, with the goal of growing COMPASS’s internship component, though Hill admits, “Development is a long process. We just show up and be responsive, and try to understand what it is that a potential employer needs from us on an entry level.”

A majority of the jobs for which COMPASS provides placement are, Hill readily admits, not adequate for fully sustainable, independent living, since higher-wage positions typically require college degrees; nonetheless, being employed is a step in the right direction. “A family still might need food stamps or state medical insurance” while working in these jobs, Hill explains, “and although a college degree is a long process, we try to keep people motivated over the long term.”

Because the COMPASS Community Collaborative is partially funded by federal Workforce Investment Act dollars, participants must be legally able to work in the United States. “Most of the COMPASS training program is done in English, and everyone must have functional English for the jobs placement,” Hill says—“it’s the law.” Lawrence, which has historically been considered the “immigrant city” of northeastern Massachusetts, is now 75 percent Hispanic, and although some homeless parents lack English-language proficiency, COMPASS connects them with community organizations that provide ESOL as a stepping stone to job readiness. Another major barrier to job placement is one’s Criminal Offender Record Information (CORI) status, as a substantial number of families have members with records of some kind. Less concerned with family members’ past than with getting them back on track, Salvatore’s does not screen for CORI, and Gemline does so only for felonies, making more clients eligible for job placement.

Graduates of COMPASS celebrate completing the program. After graduation, they will receive continued support as they seek employment and further education.

COMPASS recently held a fundraiser, which Hill describes as an exuberant “dance party where we make new friends. We connect housed people in the community to what we do.” In the process, they raised $100,000. “But that amount of money only serves about 15 families,” Hill says, “since the work we do costs $5,000 to $10,000 per family for a year of training.” In addition to events such as the dance-party fundraiser, Hill relentlessly generates money by approaching private donors; forming partnerships with other agencies; subcontracting, or receiving part of the money from grants to other organizations in exchange for doing part of the work; and, of course, writing her own grant applications. “We just got funding to do workforce development for people living in motels,” Hill says. (As part of growing phenomenon, 200 Massachusetts families currently reside in motels.)

To make sure they are known in the community, COMPASS performs outreach at the various local homeless shelters and also has connections to faith-based groups and community-development organizations. Prior to initiating its workplace component, COMPASS had already formed solid relations and a track record with key state agencies as well as other nonprofits and funders that operate in the family-homelessness arena in Massachusetts. Most notable among them is Emmaus Inc., based in Haverhill, an organization that oversees all of the state-funded shelter, transitional housing, and temporary housing in the Lawrence region and provides most of the referrals for COMPASS’s Lawrence program.

The COMPASS Community Collaborative is also currently a participant in the new Lawrence Working Families Initiative, which is in the process of creating a family resource center designed to increase the income of parents in the Lawrence public school system by 15 percent over 10 years. That citywide effort was awarded first prize in the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s Working Cities Challenge competition, aimed at supporting leaders who are reaching across sectors to ensure that smaller cities in Massachusetts are places of opportunity and prosperity for all their residents. The competition has funding and strategic partners from the public, private, and nonprofit sectors in addition to the Federal Reserve Bank.

What are Hill’s long-term goals for COMPASS? “Replicate workforce solutions throughout the state,” she says without missing a beat, “and be loud and clear.”

Resources

COMPASS Community Collaborative http://compassforkids.org ■ Little Sprouts http://www.littlesprouts.com

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Download the photo essay here.

Photo Essay:

A Lesson in Empathy

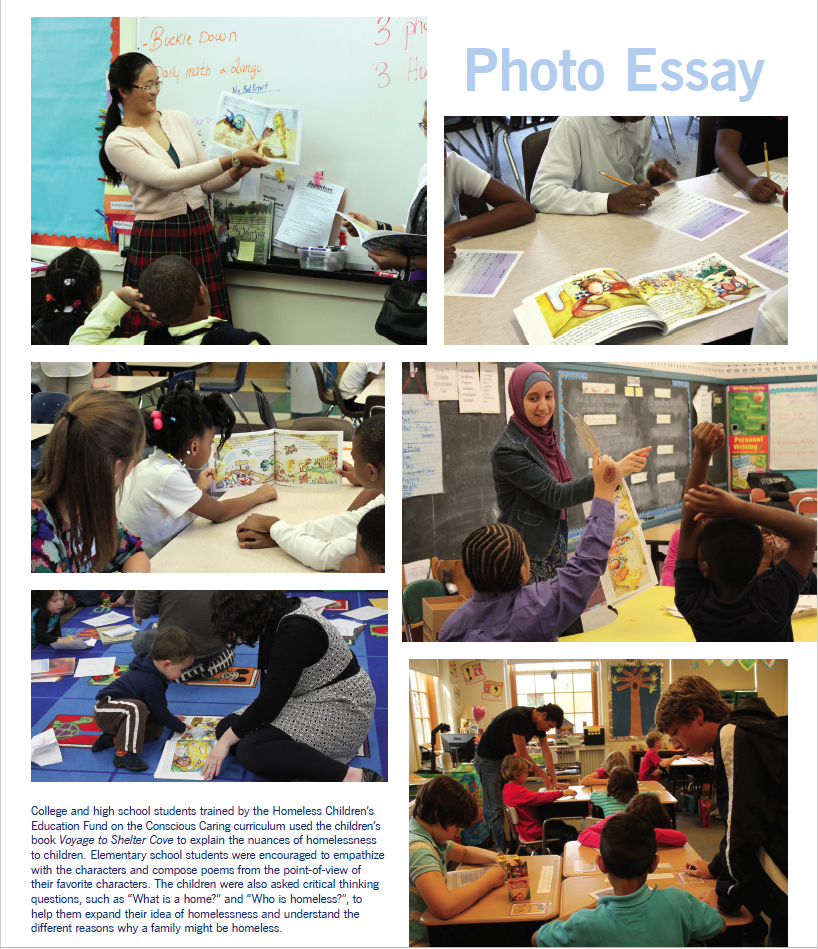

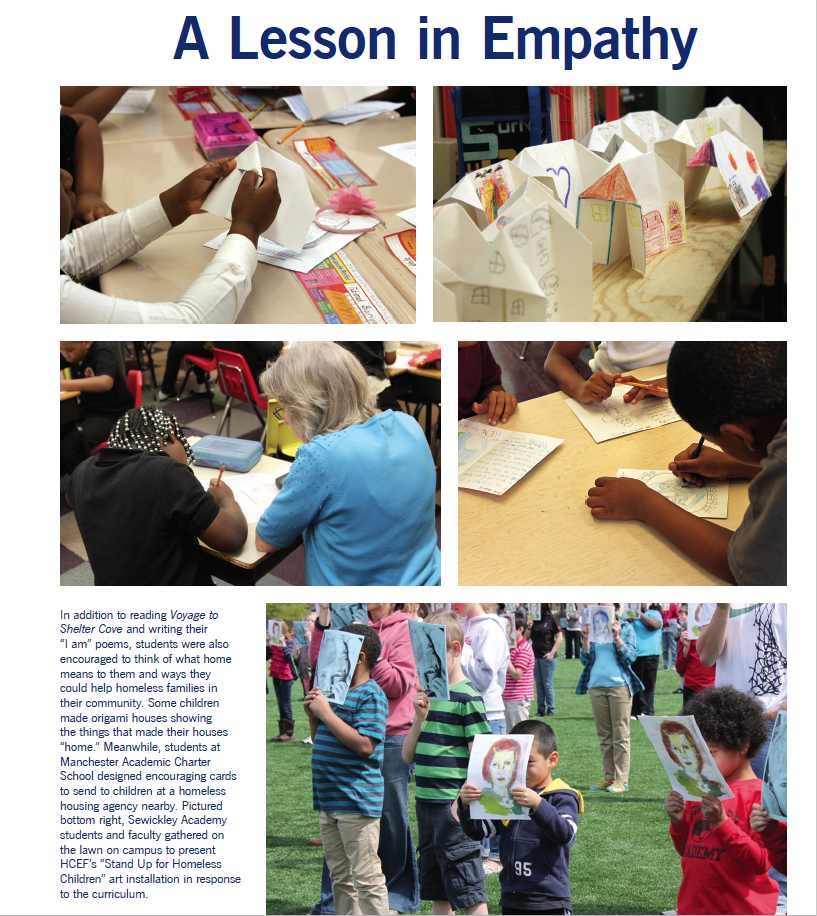

College and high school students trained by the Homeless Children’s Education Fund on the Conscious Caring curriculum used the children’s book Voyage to Shelter Cove to explain the nuances of homelessness to children. Elementary school students were encouraged to empathize with the characters and compose poems from the point-of-view of their favorite characters. The children were also asked critical thinking questions, such as “What is a home?” and “Who is homeless?”, to help them expand their idea of homelessness and understand the different reasons why a family might be homeless.

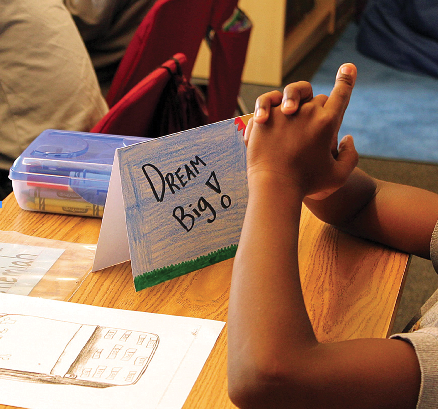

In addition to reading Voyage to Shelter Cove and writing their “I am” poems, students were also encouraged to think of what home means to them and ways they could help homeless families in their community. Some children made origami houses showing the things that made their houses “home.” Meanwhile, students at Manchester Academic Charter School designed encouraging cards to send to children at a homeless housing agency nearby. Pictured bottom right, Sewickley Academy students and faculty gathered on the lawn on campus to present HCEF’s “Stand Up for Homeless Children” art installation in response to the curriculum.

Download the photo essay here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Changing Perceptions about Child Homelessness:

A Pittsburgh Advocacy Group’s Curriculum Inspires Youngsters to Help

by Krystle Morrison

“We’re going on a trip for a few days,” the instructor, Kaitlyn Nykwest, tells the third-grade students to introduce a new topic of discussion in the Pittsburgh classroom. “Imagine you only have ten minutes to pack one backpack with everything you want to take.”

With a drawing of a backpack in front of them, the students hurry to write and draw the things they want to bring along. Cell phones and video games are popular choices, as are basketballs, stuffed animals, and other objects that take up a lot of valuable backpack space. Some remember to pack a change of clothes.

A fifth grader at Manchester Academic Charter School displays his finished card to inspire children at a homeless housing agency.

On their imaginary trip, the students stop at a hotel, where they realize they’ve forgotten to bring pajamas, toothpaste, snacks, and other essentials.

“Do you wish you had added anything to your backpacks?” Nykwest prompts. “What did you forget?” Hands go up as the students notice how much is missing and realize they can’t return home to retrieve any of it.

Then Nykwest adds, “If you had to stay away from home for a long time, what things would be hard to leave behind?” Though toys and games are on this list, the students also mention irreplaceable objects that hold memories, such as photos, journals, and gifts.

The trip is intended to be exciting, but the places they visit—including parks and hotels—as well as the urgency of the packing helps frame the rest of the “Conscious Caring” curriculum. Conscious Caring aims to give students a glimpse into the unpredictable lives of their peers who might be experiencing homelessness. The Pittsburgh-based Homeless Children’s Education Fund (HCEF), which works to meet the educational needs of children and youth experiencing homelessness in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, developed the curriculum to gently teach elementary-school-age children the truth about homelessness. HCEF Executive Director Bill Wolfe notes, “our mission is to ensure children experiencing homelessness receive the same educational opportunities as their stably-housed peers so educating their peers through this curriculum helps to foster empathy and prevent bullying, ultimately providing a better educational environment for them.”

The curriculum grew out of meetings of HCEF’s interfaith cabinet of congregations.

“We needed a tool to use to spread awareness of and teach our congregations about children experiencing homelessness,” says Darcy Osby of St. Bernard’s Parish in Pittsburgh.

Cabinet members agreed that third grade was the ideal time to take in and help spread the curriculum’s message, as these students would be most likely to share their knowledge and materials with those around them. Although third-graders were the target students, the curriculum was designed to be adaptable for different elementary-age groups. Osby adds, “I have also used the curriculum with older children up to 8th grade to give them a sense of why we do the service projects that we do and who benefits from them.”

Nykwest, who worked with HCEF for a year before being invited to help with the curriculum development, authored the Conscious Caring curriculum and piloted it at places of worship through the influence of cabinet members. Nykwest first became involved with HCEF as a volunteer reading tutor in the organization’s after-school program, while earning her B.A. in English literature and certificate in children’s literature at the University of Pittsburgh. She has since earned a master of arts and teaching degree, and she gained experience in curriculum design and implementation during an internship at the University of Pittsburgh’s Falk Laboratory School. During nearly two years of adjusting and refining the Conscious Caring curriculum, Nykwest presented it at several Pittsburgh-area schools and worked to train others to teach it. A limited number of copies of the curriculum pilot’s printed version were also distributed to participants at the 2012 National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth (NAEHCY) conference to obtain valuable feedback from educators and others who worked with homeless children and youth. The material generated interest among educators from around the country.

Partnerships in which HCEF trains university and high school students to teach the curriculum have resulted in the lessons being incorporated into elementary schools in Pittsburgh and other areas of Allegheny County. The partnerships have worked well, particularly with university students, who desire the teaching experience and want to deepen their knowledge about the laws surrounding homelessness as it relates to education.

Susy Robison introduces a group of Shady Side Academy students to the issue of homelessness and the writing and art activities they will be doing.

A main component of the Conscious Caring curriculum is Voyage to Shelter Cove by Ralph da Costa Nunez, president and CEO of the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, and Jesse Andrews Ellison, with illustrations by Madeline Gerstein Simon. The book, intended for elementary school students, tells an engaging story of a group of sea creatures who lose their homes and seek out a shelter, where they find help and purpose. Nykwest realized that teaching the book not only incorporated reading, writing, and discussion but also helped the students to better identify with someone having an episode of homelessness. The use of sea creatures makes the story entertaining for children and eases them into a discussion about the challenges of housing instability.

As Nykwest notes, “A particularly memorable activity for many students [based on Voyage to Shelter Cove] is the ‘I ’ poem.” After reading and discussing the book, students choose their favorite character and craft an “I” poem (writing, for example, “I feel ,” “I wonder ,” or “I understand ”). “During this activity,” Nykwest adds, “students engage in an empathetic exploration of characters’ feelings and experiences.” One child concluded in his poem, “I dream of everybody having a home.”

Throughout the curriculum, students are prompted with critical-thinking questions (“What is a home?”, “Is it different from a house?”, “Who is homeless?”, “In what ways might people lose their homes?”). They are encouraged to reach the answers on their own, with little prompting from their instructors. Initially, the students often voice a narrow perception of homelessness, mentioning adult men asking for money and sleeping on streets. Though they generally grasp the difference between a house and home well, the idea of families experiencing homelessness due to unfortunate circumstances is a new concept, which they come to realize through the reading of Voyage to Shelter Cove. The curriculum includes possible student answers to discussion questions and teacher responses to help guide instructors if the need arises. But the chief discussion question regarding homelessness is, “What can we do about it?”

The final assignment in the Conscious Caring curriculum is not to answer reading-comprehension questions but to complete a single sheet of paper that has at the top, “This week you will do something to help someone in need.” The curriculum’s concluding activities encourage students to think about their peers who might be going through challenging times and how the students can respond positively to those situations. The curriculum encourages students to take action in their communities in a way that meets a need. There is room for creativity here: one class designed and wrote encouraging cards to anonymous children living in local shelters. “I know you’re going through tough times,” one student wrote. “I have too. I understand your situation, and I know you can overcome it.” Others have collected supplies for HCEF’s back-to-school drive or prepared microwavable soup cups for the drop-in facility for unaccompanied youth in downtown Pittsburgh.

Sometimes the concluding curriculum activities change based on the instructors’ input. HCEF’s Conscious Caring teachers are a diverse group of individuals—often high school or university students—who are also learning new things about issues surrounding homelessness and who bring their own insights and creative ideas to the process. “When working with the university students,” Nykwest explains, “we added an activity where the elementary students trace their own hand and list five things that they can do to ‘lend a hand’ in their community. This was an engaging way to encourage students to reflect on what they can do in their own community to help others.” One group of university students also made cutouts of characters from Voyage to Shelter Cove and used them as puppets to help keep students engaged while reading the book.

The high school and university students who help teach the curriculum have reported positive experiences. “Going in, I was a little nervous that the students would have a hard time connecting with the material and answering some of the questions. But when we got in there, it was a completely different story,” a student of Duquesne University commented. She and some of her classmates spent a morning in an unfamiliar elementary school, where they quickly bonded with their fifth-grade students. “[The students] wrote very nice ‘I am’ poems. It was interesting for me as a future teacher to get to go into a classroom of fifth-graders and observe how they interact with each other.” Instructors often emphasize the usefulness of the “I” poem in driving home the curriculum’s message: “The activity familiarized the students with the common emotions felt by those experiencing homelessness: fear, uncertainty, confusion, loneliness, and feeling left-behind.” In classrooms where the curriculum instructors made return visits weeks to months later, the students remembered their names and the activities and were ready to dive into the next lesson.

HCEF is working to spread the curriculum into more classrooms, within and beyond Allegheny County. Though most of the lessons are taught by HCEF-trained individuals, the curriculum is designed for independent use. HCEF intends to continue refining it based on feedback, especially from teachers who use the curriculum in their classrooms without HCEF training. In addition, the cabinet of congregations is planning a version of Conscious Caring for adults.

Schools, Girl Scout troops, and members of faith communities often contact HCEF to ask about services children can perform on a “day of caring.” HCEF encourages them to use the curriculum as an awareness-raising outreach activity. In one instance 70 high school students participated in HCEF’s Conscious Caring training in a morning session, then presented the curriculum to 250 students in kindergarten through fifth grade that afternoon. On a Girl Scout service day, university students volunteered to teach the curriculum to 210 girls in groups of 70.

In one Pittsburgh classroom, decorated paper houses are on display by the end of the day, lining the walls like a miniature village. Each house reflects a child’s experience of home. The children now have an idea of what it might be like to lose their homes and how they can help those who have. The kids crowd around their instructors for a group hug, despite having met them just a few hours ago. What will they remember about this day? If it is only having a few misconceptions about homelessness dispelled and learning to have a little more compassion, the Conscious Caring curriculum will have been well worth the effort.

It has been well worth the effort to see students like second-grader Sariyah, who, after quietly completing the activities and listening attentively to the story, worked with another classmate who was struggling to recall details of Voyage to Shelter Cove and construct her “I” poem. The two students discussed the story together, and when it came time to share their “I” poems, Sariyah prefaced hers with this comment: “I chose Serena the Seahorse, because I want to be like her and help people when I grow up.”

Resources

Homeless Children’s Education Fund, http://www.homelessfund.org/

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Guest Voices—

Finding Nikki: Surviving and Thriving after Childhood Homelessness

by Nikki Johnson-Huston

Standing in line hoping to get a bed in a night shelter is a harrowing experience with two potential outcomes, neither of them ideal. With luck you get a place indoors to sleep, but if you’re not in line early enough, or if there are fewer available beds than expected, you’re left facing the night on the street—which, for me, my mother, and my brother, Michael, meant sleeping on a park bench.

This was the reality I knew as a nine-year-old who lived for several months on the streets and in shelters in San Diego. I spent many of my days hungry, scared, and not knowing where my next meal would come from or where we might be living on a particular day. When the things that you should take for granted, like food and shelter, are no longer guaranteed, it’s incredibility scary. It is hard for a child to fully explain what those circumstances do to you. In retrospect I know that the experience takes away your sense of trust and stability; it made me someone I would not have otherwise been. I went from being curious and precocious to being quiet and watchful, suspicious of all of the new people in my life, not knowing if they were friend or foe.

Nikki Johnson-Huston

It felt sometimes like the world had forgotten about us. But then we would meet someone who treated us with respect. Such people included those at the homeless shelter who would give us an extra blanket or pillow, or workers at the San Diego Rescue Mission—where we would get two meals a day—who gave us extra cookies and colored marshmallows to get through the days and nights. A person who gave me a snack and asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up nourished not just my mind but my spirit. For a few moments that person gave me a sense of being normal and, most importantly, helped me to believe that I had a future, complete with the luxury to decide what I wanted to accomplish.

What I remember most about being in the shelter were the sounds. We all know from experience that at night, when most of the world is at rest, sounds travel. This is especially true in the realm of shelters, where strangers, broken from the struggles of lives gone wrong, come together to share the night.

Imagine sharing a space with those suffering from various stages of mental illness, with men and women shaking with the effects of addiction or untreated medical conditions; imagine hearing the cries of mothers losing the dreams they once held dear for themselves and their children, mixed with the sounds of your own hungry stomach. You are hearing the song of catastrophic poverty that is still played throughout the shelter system in the United States on a nightly basis. For the majority of Americans, this song is played far enough out of earshot to keep us from forcing our leaders to solve this epidemic.

My mother had drug and alcohol issues that played a significant role in our being homeless, but I also believe that she suffered from the effects of her upbringing in poverty. My mother was like many people I knew growing up, who wanted better lives for themselves but gave up because of the hurt and disappointment of unfulfilled dreams and the belief that there was nothing they could do to change their circumstances. But during those nights in the shelter I held on to my dreams of having a better life. These were dreams of being a successful lawyer who had a house and plenty of food and never had to worry about being without again. Those dreams seemed far from becoming real when I didn’t know where my next meal would come from, but they were all I had—the one thing that nobody could take away from me.

“In my own family, services including addiction and abuse counseling at the homelessness stage could have had an immediate and long-lasting impact.”

—Nikki Johnson-Huston

After several months on the streets, my mother decided that she could not keep us together as a family. She sent me to live with my disabled grandmother, who was living in senior citizen Section 8 housing in Santa Maria, California. We were told that my grandmother could take only one of us. Michael was put in foster care, and we never lived together as a family again. My grandmother used welfare, food stamps, and her Social Security payments to raise me; we didn’t have much, but she provided a level of stability and security that I had never known. About three and a half years after I went to live with my grandmother, she became seriously ill, and it was decided that I would live with my mother and stepfather (whom she had met during the time we received services at the rescue mission). I spent about a year and a half with my mother, then returned to my grandmother’s home after my mother and stepfather lost their jobs and we ended up homeless again. I stayed with my grandmother until I graduated from high school.

I came to Philadelphia to attend college on a scholarship but struggled both emotionally and academically, feeling that I didn’t belong and wasn’t good enough. I didn’t ask for help and was ashamed of my past. The price I paid was to get kicked out of school at the end of my first year. Afterward I struggled for several years to find my place in the world, but I was fortunate enough to get a job as a live-in nanny for a family of lawyers who believed in me and my dream of attending law school. I went back to college at night and finally got on the right path. I am now a successful tax lawyer living in Philadelphia.

I lost contact with Michael after I flunked out of college and would not see him for another 11 years. Michael contacted me in 2004, during my last semester of law school. He was addicted to meth and had HIV. He was working on the set of the television show Frasier—which was filming its last couple of episodes—and would soon be out of a job.

I spent the last six years of Michael’s life trying to get him to rehab, trying to persuade him to go back to school to get his GED, and trying to have a real relationship with him. But in July 2010 I received a call telling me that Michael had hanged himself and was in a coma. I had to fly to California and remove him from life support. After my brother died I decided that I was going to advocate for those homeless children who felt invisible and powerless, that out of his death I could do some good.

Solutions from My Own Life

I long for the day when children will no longer face the fear and confusion of homelessness as I did at nine. It still affects my actions today, some three decades later, even though I’m now a successful attorney and speaker. This is why solving the issue of catastrophic poverty is so complex, because the repercussions continue to be felt throughout a person’s life.

There is no easy, one-size-fits-all answer to the question of how we end homelessness and break the cycle of generational poverty. I can speak, however, to what has worked in my own life and what would have enabled me to overcome my circumstances more quickly and with fewer scars.

“Generational poverty can be solved. I’m a living example of what can happen when public policy programs, such as food stamps and Section 8, are combined with solid educational opportunities and the influence of adults who believe in their children.”

—Nikki Johnson-Huston

The latest trends in addressing homelessness are programs referred to as Housing First or rapid rehousing, which aim to get homeless families into housing quickly, in order to provide an environment where mainstream wraparound services can address the underlying causes of their struggles. This sounds great in theory, and there are aspects of this approach that can certainly work for some families. But more importantly, whether the challenge is mental illness, addiction, abuse, or another factor or factors, dealing with the root issues as opposed to just the outcome—being placed into housing—is what will contribute to a long-term solution that can potentially decrease the need for these services for future generations. In my own family, services including addiction and abuse counseling at the homelessness stage could have had an immediate and long-lasting impact.

In addition, we must attempt to keep children together with their parents whenever possible. While not all mothers or fathers are suitable caregivers, we can teach life and parenting skills when the parent does not endanger the child. In the life of a child, there is no substitute for having a caring parent at home, and we need to do everything possible to preserve those arrangements. While I was actually better off in some ways going to live with my grandmother, who lovingly cared for me, my brother was irreparably harmed by our breakup as a family. Looking back, having the opportunity to stay together as a family unit and receive wraparound services would have likely saved Michael’s life. He could have been protected from some of the abuses inflicted during his time in the system, which led to his own struggles with drug addiction, homelessness, and HIV—and to his tragic death.

Mental health services will play a critical role in ending homelessness and poverty. A significant threat to mental health, especially for children, is the lack of self-esteem caused by catastrophic poverty. My family’s situation made me feel insignificant. This feeling, ingrained in me during my formative years, affected me into my adulthood. How can we expect our children to raise themselves from these depths of hopelessness when they don’t believe they hold value for the world around them or can be more than the circumstances they were born into?

Teaching these children that they are valuable and intelligent and that they have the ability to determine their own futures must be done at home, whether home is a shelter, a private apartment, or another type of dwelling. Services provided to families must include reinforcement of the idea that they hold value and can achieve. School environments must continually strengthen this message as well.

Too often, out of compassion for the struggles homeless boys and girls have encountered through no fault of their own, we reduce the expectations we have for them. We tell them by our words and actions that since they have drawn bad lots in life, it is understandable if they don’t achieve. We create a culture of low expectations, reasoning that of course these children won’t be able to read as well as others or learn tough subjects, because no one could expect them to overcome their horrendous circumstances. We may tell ourselves that we wouldn’t have been able to achieve in those circumstances, so they couldn’t possibly do so either. This is a dangerous fallacy, because for many, education is the only way out of lives of poverty.

The fact is that homeless boys and girls have already been forced to deal with the most horrific difficulties life could throw at them. The abuse, the hunger, the constant moving—those are the hard things. If they are standing in front of you after all of that, there is nothing in the world they cannot do. We need to stop telling these boys and girls things that we wouldn’t tell our own children. We would never tell our sons and daughters that it’s okay to believe they can’t accomplish their dreams. We would never try to convey to them through words or actions that their dreams aren’t realistic and that they should lower their expectations. However, every day we diminish the capabilities of the millions of children suffering from poverty by implying that they cannot achieve. While the mountains they need to climb may be higher, and the valleys they travel lower, they can succeed and live productive lives as our neighbors and peers.

When I was sent to live with my grandmother, I was put on a bus alone at the age of nine. She was there to wrap her arms around me when I stepped off that bus. One of the first things she told me was that I had been born into a different America from the one she grew up in, and she asked me what I was going to do with my life. While I may not have understood everything she said at the time, her words let me know that even though my young life was filled with tragedy and pain, I could DO something. Throughout the years I lived with her, she taught me to believe in myself and strive to live a different life. She not only asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, she made me believe that it was possible. Sitting with her, watching The Cosby Show and seeing the character Claire Huxtable—the first African-American woman lawyer I had ever seen—made me believe that I could really become a lawyer. Even with my grandmother’s love and support, my road to success was rough. Poverty still afflicted me, leading me to make many mistakes, including failing out of college. If this was the case even when I had a more stable and loving environment, then success will be still more challenging to achieve for those who do not have the benefit of this type of intervention. But the recipe for overcoming tough situations is the same for all of us, regardless of background. To be successful we must be able to hold a vision of what our lives can be. Poverty is darkness, obscuring our children’s vision of their future. We must continuously and unfailingly shine a light on their potential, to ensure that they never lose sight of their possibilities.

Generational poverty can be solved. I’m a living example of what can happen when public policy programs, such as food stamps and Section 8, are combined with solid educational opportunities and the influence of adults who believe in their children. While counseling during my childhood would have helped me to avoid pitfalls later in life, my experiences can serve as a guide to what is possible. And while the path to ending homelessness and eradicating catastrophic poverty in the United States will be difficult, we have a moral and social imperative to see it through.

UNCENSORED would like to thank COMPASS Community Collaborative and the Homeless Children’s Education Fund for providing photographs for use in this publication, as well as ICPH staffer Lauren Weiss for taking photographs for “The Write Stuff.”

Resources

Nikki Johnson-Huston http://nikkijohnsonhuston.com/

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

About UNCENSORED

Fall 2014, Vol. 5.3

FEATURES

The Write Stuff: The Power of Expression in a Safe Space

On the Right Track: COMPASS Coaches Homeless Parents on the Road to Employment

Changing Perceptions about Child Homelessness: A Pittsburgh Advocacy Group’s Curriculum Inspires Youngsters to Help

Photo Essay: A Lesson in Empathy

EDITORIALS AND COLUMNS

Guest Voices—Finding Nikki: Surviving and Thriving after Childhood Homelessness

Cover: Two actors portray characters from Writopia student Sharm’s play, Housing. The play takes a comedic look at a young man’s relationship with his sister and girlfriend as they battle over living arrangements. Writopia gives students in their program the opportunity to see their plays performed by professional actors on an Off-Broadway stage in their annual Worldwide Plays Festival.

50 Cooper Square, New York, NY 10003

T 212.358.8086 F 212.358.8090

Publisher Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD

Editors Linda Bazerjian

Assistant Editor Clifford Thompson

Art Director Alice Fisk MacKenzie

Editorial Staff Katie Linek, Lauren Weiss

Contributors Nikki Johnson-Huston, Krystle Morrison, Suzan Sherman

UNCENSORED would like to thank COMPASS Community Collaborative and the Homeless Children’s Education Fund for providing photographs for use in this publication, as well as ICPH staffer Lauren Weiss for taking photographs for “The Write Stuff.”

Letters to the Editor: We welcome letters, articles, press releases, ideas, and submissions. Please send them to info@ICPHusa.org. Visit our website to download or order publications and to sign up for our mailing list: www.ICPHusa.org.

UNCENSORED is published by the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH). ICPH is an independent, New York City-based public policy organization that works on the issues of poverty and family homelessness. Please visit our website for more information: www.ICPHusa.org. Copyright ©2014. All rights reserved. No portion or portions of this publication may be reprinted without the express permission of the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness or its affiliates.

![]() ICPH_homeless

ICPH_homeless

![]() InstituteforChildrenandPoverty

InstituteforChildrenandPoverty

![]() icph_usa

icph_usa

![]() ICPHusa

ICPHusa