Publisher’s Note

Dear Reader,

Welcome to the new UNCENSORED magazine—an all-digital version of our popular magazine that looks in depth at family poverty and homelessness across the United States, telling real stories of struggle and triumph from the perspective of families and the organizations who serve them, as well as the impact of public policies and programs—both positive and negative—on their lives. Seven years ago when we first launched UNCENSORED, we knew there were important, untold stories that needed a voice. Our focus was, and remains, to dig deeper and share important perspectives, opinions, and facts in an easily readable, enjoyable format that promotes the sharing of information and real discussions about the important issues tied to family poverty and homelessness.

In addition, each issue of the new UNCENSORED will revolve around a key topic. In this issue, we explore programs supporting the academic ventures of homeless students and the careful interplay of government and the nonprofit community in serving homeless families.

Our highlighted feature offers the new presidential administration concrete questions and ideas for looking at family homelessness through a realistic policy lens, moving beyond the simplistic “we need more housing” mantra. Instead, we deal with the more nuanced complexities of family homelessness in areas where it directly affects children: education, child welfare/foster care, and domestic violence. You will read commentary and research from experts in the field who are looking for a change in how the federal government looks at policy prescription—beyond policies that end an instance of immediate homelessness and focusing on the long-term impacts on children and the legacy they pass on to their own children.

Another feature profiles a central New Jersey-based homeless services nonprofit, Homefront, that has been serving local families for 25 years, most recently with an innovative “family campus.” Homefront’s story is both a cautionary tale and mirror of similar dynamics at play in many localities across the country where government policy decisions, both federal and local, impact an organization’s ability to serve homeless families, resulting in both innovative collaborations and an unfortunate loss of services.

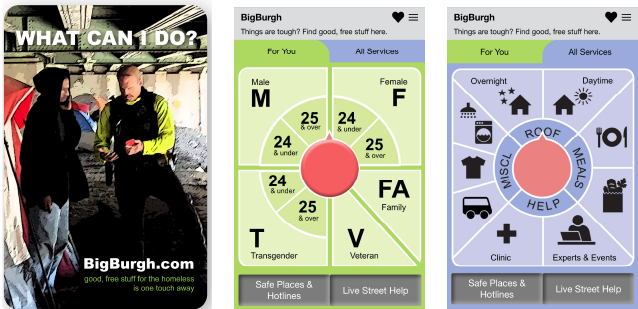

Next, we go to Pittsburgh, PA, a city and region on-the-rise, where the relationship between the local government and nonprofit community resulted in a technological solution for meeting the basic needs of homeless families, youth, and individuals. The BigBurgh app puts a plethora of services literally in the hands of those who need it while changing how the local police department is viewed by the community—a powerful testament to the impact of government entities listening and collaborating with nonprofits and those in need.

We thank you for being part of UNCENSORED’s continuing journey. We encourage you to push the conversation deeper and further, using the stories shared within as a catalyst for change. As always, please continue to share your ideas and stories with us at info@ICPHusa.org and via social media.

Sincerely,

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, Publisher

President and CEO, Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Will Homeless Families Find a Place on the New President’s Agenda?

—-Poverty and homelessness have not featured prominently—if at all—in the new Trump administration’s stated policy priorities. With a growing population of low-income families who lack a place they can call home, homeless advocates and service providers around the country are, at best, uncertain about the future.

“It’s completely uncharted territory,” said Barbara Duffield, executive director of SchoolHouse Connection and former director of policy and programs at the National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth. “You really can’t look to a past Republican administration because this is not going to be like any other Republican administration we’ve ever seen.”

It remains to be seen how many major changes to policies on homelessness will be enacted. On the other hand, the new administration’s lack of concrete policy prescriptions could potentially provide an opening for advocates to push for new ideas that were not given serious consideration in the past. What is crystal clear, however, is that service providers across the U.S. are looking to the new administration with a long wish list.

Making Family Homelessness a Visible Issue

During the administrations of both George W. Bush and Barack Obama, federal officials focused their energies and funding priorities on helping homeless veterans and single adults, based on the premise that people who sleep on the streets have the most severe needs.

In reaction, advocates and service providers say children and families who live in short-stay motels or with relatives are no less deserving of attention than single homeless adults who scrape by on the street. Due to poor living conditions, homeless children are particularly vulnerable because they are at risk for missing excessive amounts of school and may have more exposure to violence, sexual abuse, and illness. Additionally, the educational deficits exacerbated by the instability of homelessness may plague them for years.

Family homelessness advocates and service providers have long wanted the federal government to recognize and prioritize homeless families and implement a broad set of strategies to address their educational, domestic violence, child neglect, mental health, substance abuse, income, and unemployment needs.

“The constant focus on ending chronic [single-person] homelessness has consumed the national policy arena for a long time,” said Mattie Lord, chief program officer at UMOM New Day Centers, a homeless shelter and affordable housing provider in Arizona. “We have been waiting long enough for our turn. Family homelessness is a solvable problem and it’s time to give it some attention.”

“The constant focus on ending chronic [single-person] homelessness has consumed the national policy arena for a long time. We have been waiting long enough for our turn. Family homelessness is a solvable problem and it’s time to give it some attention.”

—Mattie Lord, UMOM New Day Centers

Rather than treating homelessness simply as a “housing” issue, many advocates say the government would be better served focusing on the systemic issues that cause family poverty and homelessness.

Service providers around the country say they are seeing a surge of families sleeping in cars, motels, or on the couches of friends or relatives. They are turning away families from already-full shelters. Many have mental health troubles or lack the education and job skills to earn a decent income and establish a minimal financial cushion.

They are people like Eric, a 50-year-old father of three sons in Arizona who became homeless this year. He has steady work as a restaurant cook and takes care of his two teenagers and a 12-year-old.

After deciding to move to a new apartment, Eric was unable to sign a lease after a credit check revealed that a previous landlord was seeking to collect about $1,600 in unpaid rent, which he held he does not owe. Instead, he slept with two of his sons on the street, in a train station and a bus station, before landing at a shelter. “We had no options,” he said.

Eric has been looking to find a new apartment but hasn’t had any luck. He is able to afford rent, but is encountering skepticism from landlords who are concerned he might not pay. Ultimately, he believes he will be able to find a place to live. “I’ll get out of it,” he said. What is unknown is the effect the stress and uncertainty will have on his children’s education’s and his family’s well-being.

Intertwined Problems in a World of Silos

Providers around the country emphasize that homeless families like Eric’s have complex needs and interrelated problems. Chief among them are poor education, lack of steady and gainful employment, domestic violence, and child neglect.

In Philadelphia, the People’s Emergency Center offers housing, job training, parenting and early childhood education, financial education and planning, life skills classes, and technology courses. About 90 percent of women served by the social service agency have experienced domestic violence, while two-thirds have no high school degree. Most are under the age of 25. Many have mental health problems.

Joe Willard, vice president for policy and advocacy at People’s Emergency Center, said many women are ashamed about domestic violence and are reluctant to talk about it. “You learn that only after a couple of weeks of them being in emergency housing,” he said. “Most people don’t initially tell you the whole truth.”

“I would love to see them have a huge emphasis on high school graduation for homeless teenagers. It would be a great prevention program in slowing down the number of families who come into shelter.”

—Joe Willard, People’s Emergency Center

Willard sees several ways that federal and local officials can improve how they treat families who are homeless and experiencing a multitude of problems including domestic violence and child neglect. The child welfare system, he said, should work with housing officials so that foster children would have a housing plan before they leave the foster care system, preventing them from becoming homeless after they exit foster care. Additionally, Congress should significantly increase the $65 million in annual education funding for homeless children and youth, to provide additional support for homeless students so they can finish school.

“I would love to see them have a huge emphasis on high school graduation for homeless teenagers,” Willard said. “It would be a great prevention program in slowing down the number of families who come into shelter.”

On the issue of domestic violence, Willard said the Department of Housing and Urban Development should allow more grant funding to go to domestic violence shelters. He also suggested that local officials provide more training on how to serve trauma survivors who enter housing programs.

Many people who become homeless due to a life crisis can recover fairly easily through support and temporary shelter, said Joe Lagana, founder of the Pittsburgh-based Homeless Children’s Education Fund. But homeless families in which a parent is struggling with drugs, prostitution, child neglect, and other issues need much more support.

“It’s going to require more than a house; it’s going to require services and support.”

—Joe Lagana, Homeless Children’s Education Fund

“It’s going to require more than a house; it’s going to require services and support,” Lagana said. That is especially important because research shows that homelessness experienced during pregnancy or in a child’s early years has long-term negative effects on the child’s health.

Christine Achre, chief executive officer of the Primo Center for Women and Children in Chicago said officials should invest in prevention strategies so families don’t become homeless in the first place, and understand that funding needs to be individualized and flexible. Funding should be available for a variety of child care, mental health, employment, and education services.

“We have a lot of families that are coming in with serious and persistent mental illness, with child welfare involvement, with substance abuse,” Achre said. “Families with complex challenges like these need extra support.”

Family Homelessness as an Education Issue

Across the country, advocates work tirelessly to call attention to the lack of educational opportunities for the poorest of the poor. Quality education, starting at the preschool level, is crucial in determining whether children will fall into poverty and homelessness.

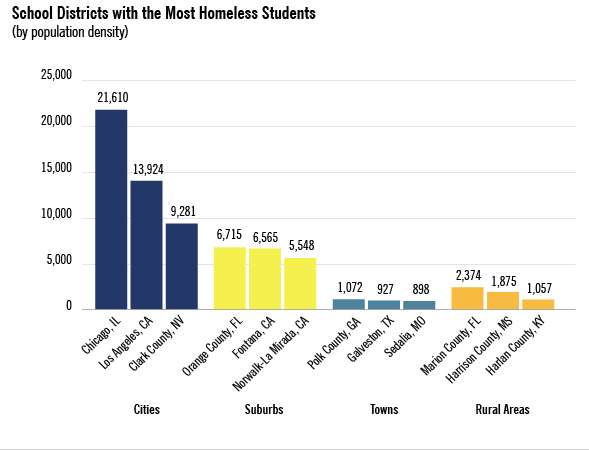

Nationwide, educators are finding that the number of homeless students is rising quickly. In the 2013–14 school year, the most recent for which data is available, a record-high 1.36 million homeless children attended public schools, according to the U.S. Department of Education, up from under 800,000 in the 2007–08 school year.

“I don’t think anybody really understands the extent of the problem,” said Susan Agel, president of Positive Tomorrows, an Oklahoma City private school for children coping with homelessness. Families “don’t want to be visible on the street … they’ll do just about anything they can just to hide away.”

“If you’re going to really stem homelessness, you need to start early, and the earlier start the better.”

—Susan Agel, Positive Tomorrows

Focusing on children—particularly young children—is key, because they can be traumatized by a period of homelessness: Almost half of children in shelters are under age six, according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

“If you’re going to really stem homelessness, you need to start early, and the earlier start the better,” Agel said. “There’s not much talk about dealing with children’s programs. … I would like to see some programs that recognize the special needs for children living in deep poverty and homelessness and provide funding for agencies that meet those needs.”

In addition to the more than 1.3 million homeless public school students, an estimated 600,000+ homeless children under five years of age will soon be entering school. Homeless students are more likely than their peers to be held back a grade, have poor attendance, fail a course or have disciplinary problems. A state-by-state analysis reveals that homeless families are far from an urban issue. In Florida, for instance, 78% of homeless students live in the suburbs. In Georgia, 39% live in towns and rural areas.

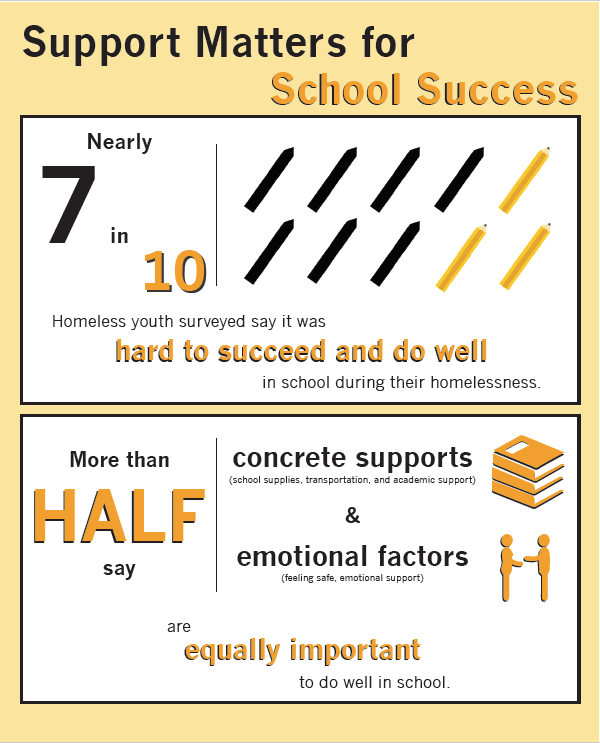

More than 40 percent of homeless students have dropped out of school at least once, according to Hidden in Plain Sight, a report on student homelessness published by Civic Enterprises in June 2016. Many never get any services: Among those surveyed, more than 60 percent say they had not been connected with any outside organization for support.

According to the report, only five states report high school graduation rates for homeless students, but those rates lag far behind those of all other students. In Washington state, for example, the overall four-year graduation rate is 77 percent, compared with 66 percent for economically disadvantaged students, and 46 percent for homeless students.

Family Homelessness as a Family Well-Being Issue

Every year, 22,000 children are removed from their families, at least partly because of inadequate housing or homelessness, according to federal officials. Ruth Anne White, executive director of the National Center for Housing and Child Welfare, said child welfare workers who encounter homeless children are put in an impossible position, forced to decide whether to separate children from their parents and place them in foster care, or allow them to stay in an unsafe location—such as inside a car in freezing weather.

“If you have not abused or intentionally neglected your child, child welfare shouldn’t even be looking at you,” White said. “A family should never be investigated for that kind of thing.”

Homeless children also tend to stay longer in foster care, White said. “They’re stuck there because the judge, in good conscience, cannot award a kid back to a mom who’s living in a car. Eventually the parent’s rights are terminated.”

In Oklahoma City, Dan Straughan, executive director of the Homelessness Alliance, said the key problems leading to family homelessness are mental health issues and substance abuse. It’s rare to encounter someone who is homeless solely because his or her income dried up, he said.

“In Oklahoma City, the key problems leading to family homelessness are mental health issues and substance abuse. It’s rare to encounter someone who is homeless solely because his or her income dried up.”

—Dan Straughan, Homelessness Alliance

A person with mental health problems is often unable to access quality medical care and get treatment for a problem such as bipolar disorder. As a result, they may self-medicate, turning to drugs and alcohol. That substance abuse, in turn, can lead to job loss, child neglect, domestic violence, and homelessness.

Straughan said the federal government should stem the root causes of family homelessness by providing increased funding for mental health and substance abuse programs. “The folks that have serious mental health issues and serious substance abuse issues are much harder to house and much harder to keep housed.”

Many providers would like HUD to grant local communities more flexibility in providing funding for programs that match local needs. Many consider HUD’s funding restrictions to be too strict and are calling for more flexibility for how they can use government funding.

“I do have days where I have to pick up the phone and say ‘I’m sorry, you’re not homeless enough for our program,’” said Beth Benner, executive director of the Women’s Housing Coalition in Baltimore.

Benner said federal regulations now require her to accept people with substance abuse problems as well as people who are sober. That is well-intentioned, she said, but it can pose a practical problem if someone who is clean and sober becomes upset that she’s sharing a bathroom with someone still struggling with drugs or alcohol. To deal with such problems, Benner said she will need to expand staffing, noting that “the government has given me no additional money” to do so.

Family Homelessness as an Economic Issue

One key underlying reason for growing concern about family homelessness is the ongoing national conversation about income polarization—the “haves” and “have-nots.” While unemployment is back below 5 percent, incomes for low-income workers have remained stagnant over the past decade and have only recently started to improve.

Meanwhile, the cost of rent has skyrocketed in recent years: A record high 11.4 million U.S. households pay more than half of their income toward housing, according to the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies. Federal assistance reaches only a quarter of those who qualify. Nearly 14 million households are left to fend for themselves in the private rental market.

Many low-income workers juggle multiple jobs with variable work hours that make it difficult to plan ahead. They are often scheduled for fewer hours than they would like, causing volatility in their income and stress at home.

In Atlanta, parents trying to escape homelessness often find themselves working temporary jobs in warehouses, bakeries, and other jobs that only pay the minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, said Jimiyu Evans, director of operations at Project Community Connections, Inc., which helps homeless people find housing.

“In Atlanta, parents trying to escape homelessness often find themselves working temporary jobs in warehouses, bakeries, and other jobs that only pay the minimum wage of $7.25 an hour.”

—Jimiyu Evans, Project Community Connections, Inc.

At such low wages, it is very difficult to save up for first-month’s rent and a security deposit in a city where rent is increasingly unaffordable. “Those wages and hours do not amount to enough for them to even qualify for an apartment,” Evans said.

Many homeless people lack the skills needed to survive in today’s workplace, Evans said. To tackle that problem, his organization provides an enrichment program to help people with employment and workplace skills, such as getting along with co-workers and creating a resume. “They don’t have the soft skills.”

What’s To Be Done?

Voices from around the country are echoing that a strategy limited only to re-housing has not and will not yield results sufficient to address the needs of homeless families. Service providers feel a pent-up frustration. They want to see attention and resources dedicated to homeless families as well as a comprehensive, effective solution.

Barbara Duffield, executive director of SchoolHouse Connection and former Director of Policy and Programs for the National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth, said, “What should drive the vision of the next administration? We propose a realistic, two-generational approach to family and youth homelessness, grounded in the interconnected and equally vital roles of housing, education, early care, and services. Indeed, without early care and education, the prospect of affording any kind of housing as an adult is slim, making today’s homeless children more likely to become tomorrow’s homeless adults.”

“… without early care and education, the prospect of affording any kind of housing as an adult is slim, making today’s homeless children more likely to become tomorrow’s homeless adults.”

—Barbara Duffield, SchoolHouse Connection

Eva Thibaudeau, director of programs at Coalition for the Homeless, Houston TX, advocates for flexibility in how federal funds are used to address homelessness: “We often get into our camps as if there is one option that would work for everyone. We know that is not true. With every population we are trying to build up choices.”

The “Great Unknown” is the new administration’s priorities on poverty and homelessness. Some suggested action items for the new administration include:

Look Family Homelessness in the Eye

- Recognize that family homelessness is growing at epidemic rates.

- Recognize that it is a local issue, and every locality is different.

- Expand the federal definition of homelessness to include families living “doubled up,” i.e., in motels or temporarily with other people.

- Recognize that flexibility is key to crafting an effective local response.

“It is simply unacceptable for individuals, children, families, and our nation’s veterans to be faced with homelessness in this country.” [June 18, 2009]

“And preventing and ending homelessness is not just a Federal issue or responsibility. It will also require the skill and talents of people outside of Washington—where the best ideas are most often found. … As we undertake this effort, investing in the status quo is no longer acceptable.” [Opening Doors: Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness, 2010]

—President Barack Obama

Meet the Educational Needs of Homeless Children

- Prioritize and increase outreach to expand high-quality early learning opportunities.

- Increase federal funding for the Education for Homeless Children and Youth program and reauthorize the Elementary and Secondary Education Act.

- Pass legislation to reduce barriers to receiving financial aid for homeless students attending college.

“Expand access to early childhood programs for children experiencing homelessness, to ensure that the trauma and toxic stress that accompanies homelessness does not disrupt brain development and compromise the foundation for future learning and health. We should also expand supports to pre-K–12 education for students experiencing homelessness, including enforcing compliance with the McKinney-Vento Act and Title I Part A provisions on homelessness and increasing funding for those programs. Without a high school degree, there is little hope of obtaining a job that pays enough to afford housing.”

—Barbara Duffield, SchoolHouse Connection

Adopt Policies that Support Homeless Families

- Invest in local low-income housing initiatives.

- Increase federal funding for child care assistance and prioritize access for homeless families.

- Increase federal funding for domestic violence shelters.

- Encourage state-level programs to reduce families’ risk of food insecurity, similar to SNAP and WIC.

“There has been a significant federal push to prioritize existing resources to end chronic homelessness over the past decade. This has impeded the ability for communities, particularly those disproportionately dependent on federal funding, to develop comprehensive planning to impact all four goals [to end homelessness.]”

—Mattie Lord, UMOM New Day Center

Target Assistance to Homeless Families

- Dedicate significant federal funds to easing family homelessness, consistent with efforts to assist chronically homeless adults and veterans.

- Align HUD’s definition of homelessness with that used by other federal agencies, i.e., to include families living doubled up.

- Collect and publicly release necessary data through HUD.

“We need to create better incentives for non-profit and for-profit developers—something both parties can agree upon.”

—Margaret Schuelke, Project Community Connections, Inc.

Views from Around America:

A Wish List for Federal Policymakers

What concrete steps can the new administration in Washington take to stem the growth of family homelessness?

by Alan Zibel

Mattie Lord, Chief Program Officer, UMOM New Day Centers, Phoenix

“The national rhetoric is that housing ends homelessness. That is true, but it is oversimplifying the issue and the needs. Why not make additional investments now that will reshape our long-term future? The return on investment in young children is significant. Children experiencing homelessness tend to have a multitude of risk factors and complexities that are not resolved with housing alone. As a nation, we need to view all children as our collective future and invest in them. They need and are deserving of services to help them achieve developmental milestones, reduce emotional problems and toxic stress, access quality education, avoid family separation due to child welfare removals, reduce family violence and increase capacity for healthy pregnancies and parenting.”

John Jeanetta, President and CEO, Heartland Family Service, Omaha

“Our wish list would include funding decisions that are data driven. To become data driven, funders should ask how successful are specific programs, continuums, states, etc. at ending homelessness? How many families return to homelessness? Are these entities cost effective in their approach? Are they using best practices? Accountability will also be key. How are health and human service departments, as well as school districts, accountable to ensure that resources—funds and/or people—are dedicated to helping homeless service and domestic violence providers solve homelessness.”

Katie Hill, Deputy CEO and Executive Director, PATH, Los Angeles

“We recognize that Opening Doors was developed and implemented during a Democratic administration, but it is our sincere hope that the new administration can recognize the objective progress that has been made because of this plan—33 percent reduction in veteran homelessness, major reductions in chronic homelessness in communities across the country, broad implementation of evidence based practices, the public and private sectors working together more effectively than ever before. We hope that this progress can be built on with the new administration, which has repeatedly proclaimed its commitment to working class families. We truly hope that this commitment will extend to the most vulnerable of those families—the ones who have lost everything, including a place to call home. We know what it takes to address family homelessness. We just need the resources and the ongoing commitment from our government partners to make it happen.”

Joyce McMillan, Director of Programming/Parent Advocate, Child Welfare Organizing Project, New York

“It is my wish that the new administration knows that poverty is not neglect and that no one wants to be poor. When people in power have a lack of understanding they add layers of surveillance to people who live in poverty. Surveillance is not support. It is counterproductive to have agencies that should embody support, help, and assistance provide only more stress. People who live in shelters in New York City live in deplorable situations with additional governmental oversight and a bunch of Catch-22 rules that prevent them from climbing out of their current situation of despair. It is my hope that the new administration will incorporate the voices of those who have been negatively affected by the ‘Good Intention’ policies put in place by people of privilege and power that don’t understand lack in any form, especially a lack of hope.”

Susan Agel, President, Positive Tomorrows, Oklahoma City

“I would like to see additional programs put in place to help with the need for affordable housing, such as subsidies so that developers would have some impetus to add low-income units to their apartment complexes. I would also like to see some programs that recognize the special needs for children living in deep poverty and homelessness and provide funding for agencies like mine that meet those needs. Currently, federal education dollars focus on mainstreaming homeless children and the supports aren’t there to help them succeed in a typical classroom. Improved mental health programs are also a big need, especially in Oklahoma. Adequate treatment is unavailable for people in poverty, which causes them to sink even further into poverty, homelessness, and child neglect.”

Joyce Lavery, CEO and Executive Director, Safe Haven Family Shelter, Nashville

“Child welfare, education, and domestic violence are not separate issues. They all impact each other and stable housing is needed the most. More funding for one without looking at root causes such as poverty and broken social service systems will not have the impact needed to reverse the trend of family homelessness. The Family Options study indicates that providing permanent housing subsidies improves other measures of well-being.”

Christine Achre, Chief Executive Officer, Primo Center for Women and Children, Chicago

“We should invest in prevention dollars so families stay housed and do not become homeless in the first place. It is not “one size fits all” to address these issues. Funding needs to be individualized and flexible, catered to the needs of the family. We must ensure funding for a number of services including home visiting, child care, trauma-informed mental health, employment, and education. Do not assume that all mainstream systems can provide everything a family needs. We must understand the importance of early learning, home visiting, and parental supports. These investments are critical to the long term success in a child’s development.”

Margaret Schuelke, Executive Director, Project Community Connections, Inc., Atlanta

“We can’t say it better than President Obama, ‘Of course, nothing helps families make ends meet like higher wages … and to everyone in this Congress who still refuses to raise the minimum wage, I say this: If you truly believe you could work full-time and support a family on less than $15,000 a year, go try it. If not, vote to give millions of the hardest-working people in America a raise.’”

Barbara Duffield, SchoolHouse Connection

“A long-term strategy for preventing families from becoming homeless again must include early care and education. It should expand access to early childhood programs for children experiencing homelessness to ensure that the trauma and toxic stress that accompanies homelessness does not disrupt brain development and compromise the foundation for future learning and health. We should also expand supports to pre-K–12 education for students experiencing homelessness, including enforcing compliance with the McKinney-Vento Act and Title I Part A provisions on homelessness and increasing funding for those programs. Without a high school degree, there is little hope of obtaining a job that pays enough to afford housing. We also need to streamline financial aid and build supports for college access, retention, and success. Increasingly, a college degree is necessary for the jobs created in our economy. In addition, a college degree is associated with better life outcomes more generally, including social, emotional, and physical health.”

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Making Progress on Homelessness:

View from a Rural State

by Angus Chaney

Small states with diffuse populations encounter unique challenges in combatting homelessness: We operate under all the federal requirements of a large city without the benefit of economies of scale—and with significant transportation barriers.

Consider the difference in cost between providing 500 shelter beds in a single city with providing that same number of beds across 14 rural counties. Now consider the same process with regard to prevention, outreach, transitional housing, rapid re-housing, affordable housing, and supportive housing.

Despite these challenges, Vermont has witnessed reductions in homelessness for the past two years. In the 2016 Point-in-Time count, we saw a one-year 28% reduction in homelessness. Because our focus has been broader than just one population, that success was seen across populations and in all regions.

We know that ending homelessness requires that policy makers address three key components: rental subsidies, services, and access to housing. Addressing only one or two in a region has limited impact.

In Vermont, we’ve made state-funded investments to address all three pieces of the equation.

Vermont’s statewide rental subsidy program provides 12-month subsidies for Vermonters who are homeless. Local non-profit and state agency partners share case management duties and tenants transition to federal Section 8 rental assistance after a year. A $1 million annual appropriation from the Vermont Legislature provides affordable housing to approximately 125 families.

Our Family Supportive Housing program provides two years of intensive case management and service coordination for formerly homeless families renting affordable housing. Our local housing review teams meet at the county level to identify housing solutions for households identified as homeless, and match them with the appropriate housing, subsidy, and services.

In addition, Governor Peter Shumlin’s executive order from April 2016 increases access to housing by setting a goal that owners of publicly-funded housing make 15 percent of their portfolio available to people who were homeless.

On the federal side, the Department of Housing and Urban Development has been more responsive under the Obama administration. We’re pleased that federal policy seems a bit more sophisticated about matching interventions such as transitional housing with people for whom it’s most effective.

The federal government could make the same amount of taxpayer money go farther and have greater impact by streamlining some of the more burdensome regulations. HUD should consider multi-year grants and reduce the number of hours states must spend applying for relatively small annual grants.

I don’t get mired in debates around Rapid Re-Housing versus Transitional Housing versus Permanent Supportive Housing because it’s not an either/or proposition.

We’ve seen the most success in regions with the capacity to provide multiple options and a strong local team and process to coordinate and match a family’s needs and goals to the right assistance.

In counties that lack the full continuum of options or emergency capacity, there’s a greater risk a family or individual experiencing homelessness will receive the resource that is most available as opposed to most effective.

In Vermont and other rural states, families with children have come to represent a significant share of people experiencing homelessness.

Our understanding of the interrelation between homelessness and trauma has grown in recent years. The stress of homelessness during a woman’s pregnancy and in early childhood can have a huge impact on developmental, educational, behavioral and health outcomes. We are developing targeted policy and programs to address this important issue.

In 2015, Vermont set an ambitious statewide goal of ending homelessness among children and families by 2020.

Some may stand back to debate whether that’s possible. Many others are already leaning in and helping with this collective push. In a single year, Vermont saw the number of homeless families with kids decline by 22 percent to 156 this year from 199 a year earlier.

Any country that can figure out how to put people on the moon or contemplate expeditions to new planets can find housing for its citizens. To be successful, every state will continue to need federal resources that are flexible enough to address the unique needs of local communities.

Angus Chaney is chair of Vermont Gov. Peter Shumlin’s Interagency Council on Homelessness and Director of Housing at Vermont’s Agency of Human Services.

Resources

Homeless Children and Youth, Child Trends Databank. (2015). www.tinyurl.com/hh35efx ■ Coalition for the Homeless www.homelesshouston.org Houston, TX ■ Harvard Research Center, The State of the Nation’s Housing 2016 www.tinyurl.com/h6ovd57 ■ Homelessness Alliance www.homelessalliance.org Oklahoma City, OK ■ Homeless Children’s Education Fund www.homelessfund.org Pittsburgh, PA ■ Ingram, Erin S., John M. Bridgeland, Bruce Reed, and Matthew Atwell. Hidden in Plain Sight Homeless Students in America’s Public Schools. A Report by Civic Enterprises and Hart Research Associates (2016) www.tinyurl.com/j8teg89 ■ Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness www.ICPHusa.org New York, NY ■ National Center for Housing and Child Welfare www.nchcw.org University Park, MD ■ People’s Emergency Center www.pec-cares.org Philadelphia, PA ■ Positive Tomorrows www.positivetomorrows.org Oklahoma City, OK ■ Primo Center for Women and Children www.primocenter.org Chicago, IL ■ Sandel, M., Sheward, R., and Sturtevant, L. Compounding Stress: The Timing and Duration Effects of Homelessness on Children’s Health. Insights from Housing Policy Research. June 2015 http://www.childrenshealthwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/Compounding-Stress_2015.pdf ■ SchoolHouse Connection www.schoolhouseconnection.org Washington, DC ■ UMOM New Day Centers www.umom.org Phoenix, AZ ■ U.S. Department of Education www.ed.gov Washington, DC ■ Women’s Housing Coalition www.womenshousing.org Baltimore, MD.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

A 25-Year Struggle to Put Families First:

HomeFront New Jersey’s Story

by Linda Bazerjian

Traffic signs point to the Trenton-Mercer Airport, but the GPS veers off the main roadway toward a three-story pink building behind a shiny black wrought-iron fence. A small public bus shelter stands empty just outside the fence. Visitors are greeted by a sign on the building that reads, “HomeFront Family Campus,” in huge black letters. Locals will tell you that it was the site of a Marine Reserve Center until its closure in 2011. What was once part of the military industry has been transformed into a vital community resource for Mercer County families.

A Building That Fosters a Sense of Community

When you walk through the floor-to-ceiling glass doors of the public entry way, there is a calmness amid an undercurrent of activity that runs counter to the empty industrial park just outside. Another entrance on the side is used for the 38 homeless families with children who reside in the multi-purpose building to give them privacy and a sense of normalcy in their temporary home. An attentive staff member tries to fix a beautiful water feature mounted on the lobby wall. A staff meeting is taking place in the main hallway’s glassed-in “ArtSpace,” an area which does double duty as a therapeutic art studio for homeless and formerly homeless clients and a meeting room. The giggles of young children as they mimic the letter sounds their teacher makes comes from a daycare room down the hall. One resident mom who is picking her child up from daycare gets a big hug and tells a visitor, “she never wants to leave daycare,” pointing to her daughter. “At first I was worried; I thought I was doing something wrong that she didn’t want to be with me and liked daycare better but then I got it,” she continues. “I’m doing something right.”

From an interior design and program model perspective, the “family campus” main building is more like a college campus in miniature than a homeless shelter. Each client room has a private bathroom for the family. Common living spaces are strategically placed throughout campus. Some are tiny nooks with rocking chairs to encourage one-on-one parent-and-child reading time. Others, like the library, are sun-filled with wall-to-wall books, bean bag chairs, and child-friendly rugs. There’s even a small salon to encourage mothers to do each other’s hair while talking about their day, helping to build a support network, and “save money,” as one resident says while rocking her infant son in her lap as another resident is working on her hair.

HomeFront New Jersey’s new family campus has an on-site daycare that is licensed to serve 30 children, including slots for Early Head Start.

Connie Mercer is the founder and executive director of HomeFront, a Mercer County, New Jersey-based social services nonprofit. Mercer believes the solution to family homelessness lies in the models advocated by New York City’s Homes for the Homeless (HFH). HFH advocates community residential resource centers to address the underlying causes of family homelessness: domestic violence, trauma, incomplete education, and lack of job skills or job history. Simultaneously, the community residential resource centers meet the short-term basic and long-term developmental needs of the children living there. At the top of the priority list are safe housing, food, daycare, after-school activities, recreation, and health care. The family campus of HomeFront realizes HFH’s vision for the community resource center.

… the “family campus” main building is more like a college campus in miniature than a homeless shelter.

The bottom floor of the three-level family campus is the hub for workforce development and basic education. Through its Hire Expectations program, clients who currently or previously resided at HomeFront’s shelter, as well as in the community, participate in a variety of classes and workshops on site, such as a six-week customer service certification. Clients can stop in to talk with one of the staffers for one-on-one assistance. They can take high school diploma coursework on-site in preparation for the TASC test (formerly the GED). HomeFront partners with Mercer Community College so those who pass the test can walk in high school graduation ceremonies or move on to college classes.

HomeFront New Jersey’s new family campus has an on-site daycare that is licensed to serve 30 children, including slots for Early Head Start.

Daryl, a client who will soon start working at TD Bank, talked with Lynne Wise, head of HomeFront’s workforce development programming, about a one-on-one tutoring session she had with a HomeFront volunteer who had worked for TD Bank. “I got the job. I start Tuesday but I was worried that maybe the job was a little too advanced for me,” she says, “But then getting to talk with someone who actually worked there, who could explain things like loan interest … I know I’m ready.” Mercer helped Daryl find a job, prepped her for the interview, and set her up with one of the organization’s vast network of volunteers to allay her new-job jitters. Mercer, who seems to knows every client and person who walks through the campus, reminds Daryl, “make sure you go to the HomeFront FreeStore and stock up on some clothes for work so you are set.”

For more than 25 years HomeFront has been serving the community and amassing public goodwill in central New Jersey. The Family Campus is the most recent addition to a growing list of services the nonprofit provides to the surrounding community. Its programs are designed to help pull families out of poverty and homelessness for the long term. Mercer does not subscribe to the notion pushed by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) that in all cases homelessness is ended the instant a family is moved into housing. Mercer finds one-size-fits-all policy edicts meaningless on the front lines of family homelessness. Although she often deals with the harsh realities of government policies on her organization’s ability to meet the needs of the community it serves, it’s the longer term results she is after. To achieve those results, Mercer feels a variety of approaches work better because every family needs a different intervention or a different level of intervention. As she puts it, “I wear a size ten shoe. One-size-fits-all doesn’t work for socks in the same way that it doesn’t work for policy solutions.”

When Funding and Policy Priorities Align …

More than 200 families with children comprised of over 600 family members have entered the family campus’ doors since it opened in August 2015. On any given night up to 38 families are staying in one of the rooms on site. That number doesn’t account for the thousands of homeless families and working poor whom the organization helps keep afloat through its homelessness prevention program, rapid rehousing initiative, permanent supportive housing, after school and evening activities and summer camps for homeless children, food pantry, and furnishing-a-home initiative.

Similar to many localities around the United States, Mercer County finds its most concentrated poverty in its urban city center, Trenton, where the median household income in 2010 was almost half that of the county ($36,000 compared to $71,000). However, the families HomeFront serves come from across the county. Most are young, single African-American mothers in their early 20s with one or two children who come to HomeFront directly from emergency shelter or because they’ve been kicked out of living with family or friends. The majority of children are under the age of one.

ArtSpace’s clients engage in therapeutic art programming aimed at alleviating the trauma of homelessness. Client work is showcased in galleries at local private schools and at the offices of HomeFront’s corporate partners.

The impetus for the redevelopment of the old Marine Reserve Center was the impending sale of the property where HomeFront’s main shelter was previously located. HomeFront now owns both the facility and land where the family campus stands. HomeFront will save over $300,000 a year because it is no longer leasing space. The organization can put that money to better use, as well as help more diverse clients. For the first time in its history, HomeFront can also provide shelter to fathers and intact families. Provisions in its previous lease prohibited men from living at the shelter.

At the ribbon cutting for the family campus in 2015, New Jersey State Department of Community Affairs Commissioner Chuck Richman noted he had visited the property before it was acquired and didn’t originally share Mercer’s vision for how the site could be transformed into a one-stop-shop of services. But Richman did have faith that Mercer could make it happen.

“Mercer believes that it is an example of government involvement gone right.”

“Acquiring excess government land is a complicated process,” says Mercer, who has never run away from complications. She founded HomeFront 25 years ago when she was a corporate recruiter, and a pediatrician friend told her about the plight of families who were living along Route 1 in shabby motels. Mercer immediately mobilized her extensive contact list to bring food and other necessities, and hasn’t stopped since.

“It was a blessing that homeless providers were given a leg up,” she notes when talking about the priority that service providers are given in the labyrinthine process of acquiring decommissioned military installations.

While the process was arduous, Mercer believes that it is an example of government involvement gone right. She is also effusive when it comes to Commissioner Richman, calling him “the salvation of the nonprofit community in New Jersey.” He is willingness to see, embrace, and enact the visions of agencies like HomeFront. The site for the new campus may have been acquired for free, but the price tag on renovations to the main building was six million dollars. Funding was made possible through a public-private partnership, coming from the New Jersey Department of Community Affairs and HomeFront’s generous base of donors. Throughout the new campus, everything from individual resident rooms to the cafeteria are marked with tasteful plaques commemorating the individual, foundation, or grant that helped make the campus a reality. Even the boiler and mechanical room have plaques.

When Priorities Compete

Although the HomeFront Family Campus was created in part thanks to government priorities and officials who incubated innovation, HomeFront is now struggling with other realities common to nonprofits: cuts in funding and changes in policy priorities that impact services. Much of the government funding used to provide social support by groups such as HomeFront stem from public policy that is initially made at the federal level. Programs are implemented, and partially funded, at the state and local level with each entity contributing a portion of the funds. Local needs and resources change policy priorities. According to advocates and news reports, cuts to approval of emergency assistance by the state ranged from 25 to 47 percent. In the past two years alone, HomeFront has seen about half a million dollars less in its total government funding, yet the organization hasn’t seen a decrease in households seeking their services.

Each state administers its own social safety net. In recent years, the State of New Jersey has cut funding, reinterpreted rules governing assistance, and created greater efficiency. According to advocates from groups like the Anti-Poverty Network of New Jersey and the New Jersey Coalition to End Homelessness, New Jersey’s policies are shortchanging its most vulnerable citizens in three ways. First, by providing inadequate monthly stipends to public assistance recipients. Those stipends have not seen an increase in almost 30 years. Second, the advocates say the state has purposely denied more applications in the past two years to reduce the overall aid distributed. Third, they say, the state scrutinizes applications to ensure that only the neediest receive aid. This is a common strategy as government agencies at all levels strive to serve all residents, sometimes requiring more efficient systems of checks and balances or adjusting policy priorities to stretch scarce government dollars.

HomeFront offers extensive adult education and training for clients living in the shelter and from the greater community.

In written testimony to a state senate committee on the topic earlier this year, Elizabeth Connolly, Acting Commissioner of the NJ State Department of Human Services said, “Emergency Assistance, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and General Assistance enrollment has decreased dramatically. While some suggest that this decrease is the result of an effort by the state to restrict access to social services benefits, that statement is simply not true.”

Part of the State’s reasoning for cutting funding to such services is based on the data: a precipitous 40 percent decrease in the number of individuals seeking and receiving financial assistance through emergency and general assistance programs such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). A State Office of Legislative Services analysis found that the number of monthly TANF recipients went from 103,202 in 2012 to just 56,239 in 2016.

Further, the state plans to increase funding for compliance-review teams to go over the decisions of local welfare agencies, believing that this will increase efficiencies so that only the neediest receive aid.

One of the more progressive on-site services HomeFront provides to adults, children, and families is counseling and mental health services through a partnership with another local nonprofit, the Family Guidance Center. Beth Hart, the director of development for Family Guidance Center says “having clinical social workers and an advanced practice nurse on the family campus takes all the barriers away for homeless families who need mental health treatment.”

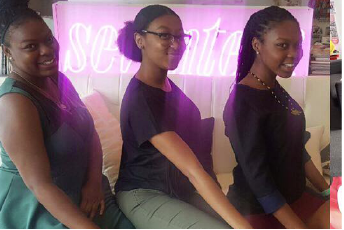

HomeFront founder and executive director Connie Mercer (far right) cut the ceremonial ribbon at the opening of the organization’s new family campus along. Sheila Addison, Family Preservation Center Director (left) and WorkFirst Director Lynne Wise (with scissors).

Hart notes that the Family Guidance Center caters to the whole family. “Children experience a lot of loss and anxiety as a result of homelessness. They need to develop coping skills to deal with those feelings just like adults do.” Family Guidance Center counselors help to provide a safe and secure environment by providing counseling services for the children and working with their parents so that they can help the parent and the whole family through the experience of homelessness. This work extends beyond counseling sessions to referrals to afterschool programs, working hand-in-hand with school guidance counselors, and getting families tied into the right health insurance. All of this is funded through a FGC grant obtained through a local foundation that supports the collaborative nature of HomeFront and FGC.

Beth Hart believes that foundations are fulfilling an unmet need. “To my knowledge, there is no public funding being provided for this type of collaborative project.” In fact, she points to recent trends among states, with New Jersey being the latest, to move to a fee-for-service reimbursement structure for outpatient mental health and substance abuse treatment providers over block grants. “This is going to have a devastating impact on our rate. Anyone who works with mentally ill or substance-using clients knows that they often miss appointments. We will no longer be paid when that happens.”

“… having clinical social workers and an advanced practice nurse on the family campus takes all the barriers away for homeless families who need mental health treatment.”

Recent cuts in other areas have caused HomeFront to shutter a program that worked with pregnant homeless mothers. The next program that may be on the cutting block, or may have to change how it runs, is the on-site daycare, the Atkinson Child Development Center, a licensed childcare facility for 30 children located at the family campus. It includes eight Early Head Start slots and 22 slots for families sheltered at the campus or who are utilizing its array of services. Mercer has her fingers crossed that the state will welcome a recent proposal for a pilot program to establish a secure funding mechanism for childcare providers, like HomeFront, who serve an extremely high-need population like homeless children. Things like stringent attendance requirements and the inability to enroll new children throughout the year are barriers in the existing funding structures for these providers. The transient nature of—and the inability to plan ahead for—slots in a childcare room come with the territory of working with homeless families and children but funding mechanisms haven’t caught up with the real needs. For instance, HomeFront typically sees three to five new families a week. Currently, its childcare program is running at a $190,000 a year deficit because the organization has been picking up the slack. Without an intervention or change in policy that allows funding to be used more flexibly, children who don’t meet the various voucher and emergency assistance or Work First criteria will not receive funding support to attend the childcare center. The States of Washington and Massachusetts have found creative solutions to the funding barriers for serving homeless children by offering more child care subsidies and creating designated slots for homeless children with childcare providers.

In 25 years, Mercer says, “we’ve never turned anyone away, but we’re very close to stopping that policy because of financial constraints.” Homefront is stepping up its already active development efforts in the hopes of compensating for some of the changes in government priorities.

Each family at the Family Preservation Center lives in a safe, clean private room including a bathroom. Upon arrival, they receive essentials, such as toothpaste and laundry detergent.

“I’ve been a volunteer,” says self-described community member, advocate, volunteer, and former head of the Educational Testing Service (ETS) social investment fund Eleanor Horne. “When my grandson was 14 he volunteered at HomeFront and it changed his view of the world. It made him realize how fortunate he was. He had no idea how many resources it takes to support a family in a minimal way. At 24 he still talks about his experience volunteering.” She continues, “I’m concerned about homelessness.”

Horne believes that HomeFront is a win-win for corporate and foundation funders, calling it a “clean” charity, one that both corporations and their workers feel good about assisting. It provides not only opportunities for monetary support, but also for employees and their families to get involved and learn about the issue first hand through activities like backpack drives and spending time at the shelter with the families.

“Currently, its childcare program is running at a $190,000 a year deficit because the organization has been picking up the slack.”

At 25 years and counting, Mercer’s experiences echo those of Horne and her grandson. “I just got off the phone with Angel, who told me her book had just been accepted by a publisher,” said Mercer. “Angel is now a PhD-level nurse who teaches other people to be nurses. When I first met her, at a grim welfare motel in the mid-nineties, she was a 12-year-old child who had not been to school in three years. She had instead been crisscrossing the country with her very mentally ill mom. Our volunteers wrapped her in services and she began to blossom.

“Yesterday I was checking out at Sam’s Club and the cashier said shyly, ‘Thank you, HomeFront helped me and my baby last year. Now we are good.’ Friday, one of our young woman passed the math portion of her high school equivalency test,” says Mercer. “So how can I not do the work I do?”

The playground is part of the “family campus.” It includes toddler-friendly areas, as well as activity centers designed for the developmental needs of older youngsters.

Resources

HomeFront http://homefrontnj.org Lawrenceville and Ewing, NJ/ ■ Homes for the Homeless http://hfhnyc.org New York, NY// ■ Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, A New Path: An Immediate Plan to Reduce Family Homelessness. February 2012. https://www.icphusa.org/new_york_city/a-new-path/ ■ New Jersey State Department of Community Affairs http://nj.gov/dca/ ■ Hearings Before the State Oversight Committee, 2016 Leg. (NJ 2016), written statement of Elizabeth Connolly, Acting Commissioner, NJ Department of Human Resources, p. 20–25. ■ http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/legislativepub/pubhear/slo09292016_appendix.pdf/ ■ Brush, Chase. “Advocates Clash with Administration Over Number of Poor in New Jersey,” NJ Spotlight, September 20, 2016. http://www.njspotlight.com/stories/16/09/30/advocates-and-administration-clash-over-number-of-poor-in-new-jersey/ ■ Family Guidance Center Corporation http://www.fgccorp.org/ Hamilton, NJ.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

A Life-Changing App Grows in Pittsburgh:

Nonprofits, Government, Corporations, and Homeless Youth Team Up for a Solution

by Mari Rich

“My life would undoubtedly have been much easier had BigBurgh.com existed when I was homeless,” Grace Enick asserts. Enick—who spent much of her teens and early 20s battling depression, untreated trauma, and addiction—was referring to a new mobile-optimized website aimed at connecting Pittsburgh residents in need with important services. “When you’re out on the street, as I was sometimes, you’re constantly at risk of being exploited, sexually and otherwise,” Enick says. “You might not know where your next meal is coming from or where you’re going to sleep that night. If I was able to access immediate and effective support when I needed it most, my story might have turned out differently.”

A Casual Chat Sparks a Solution

The idea for BigBurgh.com originated with Joe Lagana, the founder of the Homeless Children’s Education Fund (HCEF), a nonprofit group he established in 1999 to serve homeless students in Pennsylvania’s Allegheny County. The organization—which he launched after looking for volunteer opportunities in the early days of his retirement from posts such as a teacher, guidance counselor, and, ultimately, head of a consortium of more than 40 school districts—runs afterschool and summer programs, builds and equips learning centers within partner shelters, distributes much-needed school supplies to homeless students, and more.

Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto shows off the app at an August 2016 press conference. Peduto, who made ending homelessness a priority of his administration. He pledged government support to maintain the site once the trial period ends.

One day, casually chatting with Maurita Bryant, a now-retired assistant chief with the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police, Lagana commiserated with her about the difficulties of helping homeless individuals whom members of the force encountered while on patrol. Pittsburgh officers kept folded up in their uniform hats typed lists of shelters and soup kitchens, and when they met someone experiencing homelessness, the best they could do was to pull out the sometimes tattered and rarely updated sheets of paper and start making phone calls, in an attempt to match the person with a needed service. Now, well into the 21st century, they both agreed, there simply had to be a better way. Why, they asked, invoking Apple’s famed slogan, wasn’t there an app for that? Because of the open dialogue between a city official and a nonprofit advocate, a potentially life-saving tool was born.

Pittsburgh, the center of Alleghany County, is widely considered a city on the rise; once known as a solidly blue-collar hub of steel-making and manufacturing, it was recently named a top destination by both the well-respected magazine Travel & Leisure and the travel service TripAdvisor, and in 2015 it was recognized by Zagat for the quality and variety of its restaurants. Despite those markers of upward mobility, homelessness is a serious problem in the area. During the 2014–15 school year, Allegheny County schools identified 3,000 students experiencing homelessness—a figure that Lagana and HCEF suspect is low, given the number of children who might not have been included in that survey for various reasons. “These kids don’t walk around wearing hats or T-shirts proclaiming that they’re homeless,” Lagana explains. “And when they’re asked, they might not admit that they’re homeless, either because they’re embarrassed or because they simply don’t think of themselves with that label; some prefer to think of themselves as simply going through a rough patch or having some trouble.”

“Pittsburgh officers kept typed lists of shelters and soup kitchens folded up in their uniform hats …”

When the conversation with Bryant sparked the idea for an app, Lagana immediately knew whom to call: Bob Firth of the local firm Informing Design, Inc., which is widely recognized throughout the region for translating complex sets of data into simple and easy-to-read maps. (Among the company’s triumphs is the large and colorful sign system that has guided Pittsburgh motorists to major destinations and parking throughout the city for the last two decades.) Firth, a forward-thinking man who relishes a challenge, agreed to donate his services, and Lagana raised $150,000—enough, he estimated, to launch a two-year pilot program—from such local groups as the Pittsburgh Child Guidance Foundation, the Buncher Foundation, the Birmingham Foundation, and the Terry Serafini Family Foundation. The money raised was earmarked to maintain the site and continually update it once it was launched.

“I value the inclusive process that was undertaken because it was done with great respect and compassion for individuals living through tough times,” says Pamela Golden, the executive director of the Pittsburgh Child Guidance Foundation, a group that saw BigBurgh’s promise early on and provided funding.

Firth began by studying the issues facing homeless youth, learning what resources were available in Pittsburgh to address those issues, and figuring out what type of online interface would be the most user-friendly yet comprehensive and efficient.

“We decided to design a mobile-optimized website that could be accessed easily from a cell phone, rather than something that had to be downloaded from an app store,” he recalled. Firth explained that outlets like iTunes or Google Play sometimes make users think—mistakenly—that they must enter a credit card number in order to create an account and download even a free item. They wanted as few real or perceived barriers to accessing information as possible.

“We also had to make sure the search function worked better for this population than the usual Internet search engine,” he said. “If you are a homeless person looking for free dental care, and you type that phrase into Google, for example, you’ll get thousands of hits. The vast majority of them, however, will be advertisements for doctors offering free initial consultations, after which you’d be expected to pay full price for treatments. It’s a lot to wade through if you’re out on the street and in pain from a toothache. Additionally, if you have a limited data plan, you don’t really have the time to scroll through useless listings.”

“… a lot of the homeless and their problems are never seen by anyone not working directly in the field.”

Lagana and Firth were met with some skepticism from government officials unfamiliar with Pittsburgh’s homeless population. According to the skeptics’ way of thinking, the plan might work if police and outreach workers could be convinced to use the service while out on the streets, but anyone unable to afford basic shelter could surely ill afford to maintain a cell phone and would not be able to take advantage of it themselves.

As the project’s developers knew, however, those naysayers could not have been more wrong. Surveys and studies have shown that nationwide more than 60 percent of homeless youth have mobile phones and consider them to be essential lifelines—every bit as important as food or clothing. An even greater number—85 percent—went online regularly, if not through their phones then using the computers at libraries, drop-in centers, or other public facilities.

“My biggest challenge was to first get everyone I needed at the table, at the same time,” Lagana recalls. “I wanted the support of Allegheny County officials, Pittsburgh’s mayor, the Bureau of Police, the District Attorney’s office, and the Sheriff’s Department. Then, once they were sitting at the same table, I had to convince them that there really was a solution to what seemed to be an ‘invisible’ problem—because remember, a lot of the homeless and their problems are never seen by anyone not working directly in the field.” He continues, “It was smooth sailing once I brought in a few homeless youth to speak to them and explain how much they relied on their mobile phones and how useful something like this could be. I was delighted and impressed that everyone got right on board.”

Build It Right and They Will Click

Firth knew that in order to attract users—particularly homeless youth—BigBurgh.com would need to be as eye-catching and easy-to-use as one of those popular games like Angry Birds or Candy Crush. Thus, open the site and you’re greeted with the no-nonsense line, “Things are tough? Find good, free stuff here,” along with a colorful dial that allows users to personalize the experience by clicking on their age group and gender (including transgender) and whether they are a military veteran or part of a family group with children under 18 seeking services. (If a user wants instead to see everything on offer, they can simply skip the first step.)

The next screen displays possible needs—a cooked meal or groceries, a bed for the night or a daytime drop-in center, clothing, a ride, medical care, and more—each represented by an easy-to-understand icon. Also included is a button for “Expert Help,” which provides listings of parent-support groups, legal aid, behavioral health counseling, job-search resources, and more. In just a few clicks, users can find exactly what they need; a woman over 50 would not waste time traveling to a shelter for transgender youth, for example, or a 30-year-old army vet seeking a medical clinic would not be directed to a facility for elderly substance abusers.

Officer Ron Spangler speaks about BigBurgh.com at a press conference, explaining how the site helps police connect those experiencing homelessness to much-needed resources.

The listings are given in order of proximity to the user’s geo-location, with maps and full information about a facility’s hours and policies. “Sometimes just listing an address is insufficient,” Firth explains. “If the entrance to a building is around the back or if someone trying to gain entrance must ring a specific bell, we’ll note all of that.”

Even fewer clicks are required to access “safe places and hotlines” and “live street help”; those services are available through two buttons at the bottom of the screen. (Although Firth dislikes the term “panic button,” it is loosely applicable in this case.) The first button quickly directs users to resources for victims of domestic violence, members of the LGBT community who may be suffering harassment, and others in need of immediate help. The latter button allows a user to initiate a live chat with an outreach worker from one of the county’s social-services agencies, choosing from such options as “in physical distress,” “need food,” or ‘just need someone to talk to.” The outreach worker then has the option to render advice remotely if appropriate or to drive to the user’s location to help in person.

“… in order to attract users—particularly homeless youth—BigBurgh.com would need to be as eye-catching and easy-to-use as one of those popular games like Angry Birds or Candy Crush.”

The platform itself serves as a sort of living map of resources in the area. If, for example, the data shows that it is more difficult to find dermatologists willing to work with the homeless than other medical specialists, site administrators from Firth’s office can note that discrepancy and try to remedy the situation.

“There’s a hierarchy of needs, so we knew it was important to first address basic things like shelter, food, and medical care,” Lagana explained. “Once those fundamental and life-saving needs are met, we can work on educating BigBurgh’s users; I don’t mean educating in just the academic sense, because it goes far beyond just advising them where they can enroll their child in Pre-K or complete their GED. We educate them on a broader level about everything they need to get their lives back on track.”

Improving Relationships on the Streets and Around the Community

The first users of BigBurgh.com were eight Pittsburgh police officers working under the leadership of Commander Anna Kudrav who underwent training and deployed the service out on the streets. In addition, a small group of homeless youth were given prepaid cell phones with which to access the site. It was an immediate success. During a period of beta testing, which commenced in April 2016, BigBurgh.com was used some 1,500 times (a figure that excludes the times it was accessed during training sessions), and when it went live in August, it began receiving an average of 3,000 hits a month.

The police were especially enthusiastic about the benefits. Encountering someone with foot problems, for example, they could find a source of free podiatric care, discover if a shuttle service or other transportation option was available, and make sure the person could find a good meal after being treated—all with just a few clicks.

Left to right: Commander Anna Kudrav, Joe Lagana, and Officer Spangler confer at a press conference on BigBurgh.com. Commander Kudrav led the team of officers who first deployed the service out on the streets.

“BigBurgh.com is transforming our relationship with the community,” Commander Kudrav asserts. “Sometimes the police are featured in the media in a negative light, and homeless people might tend to feel uneasy when we approach them. Now, however, it’s becoming accepted that we are out on the street to help and that we have the resources to get people exactly what they need exceptionally quickly. That makes our relationship with the homeless much stronger than it’s been in the past and eases the tensions that can arise when a uniformed officer interacts with a member of a vulnerable population.”

Chris Roach, an outreach worker with the nonprofit group Operation Safety Net, believes that BigBurgh.com has the potential to strengthen other types of relationships as well. “Sometimes the wider community takes a ‘not in my backyard’ attitude to the homeless, refusing to make eye contact with them or even calling 911 as though they were a nuisance to be swept away instead of fellow human beings,” he says. “I think one of the primary reasons for that type of behavior is that people simply don’t know how they can help. The problems of the homeless can seem insurmountable to the average bystander. But if someone can access BigBurgh.com when they see a homeless person in need, they have a very concrete, practical way to help, and that’s a very empowering thing. People, on the whole, really do want to help when they can.”

Pittsburgh Child Guidance Foundation’s Golden adds, “BigBurgh is easy to use and was created for both people in need and for those in a position to help them. The community response to BigBurgh tells me that it is a service that will make a positive difference in the lives of many people.”

Besides its ease of use and comprehensiveness, early users have pointed out that among BigBurgh.com’s key attributes is that it’s updated regularly; if a shelter changes its policies or a medical clinic shutters operations, those changes are reflected in a timely manner. “You can’t treat a service like this as a shiny new trinket and then lose interest in it,” Firth cautions. “From the beginning, we budgeted for regular maintenance and updating. The fact is that if a user gets bad, out-of-date information once or twice, they’ll just stop accessing the site altogether.” To avoid that, Firth and his staff repeatedly call and email the service providers listed on the site, and once a week they make in-person visits to several providers on a rotating basis. “You can’t wait for a social service worker to contact you with updated information,” he says. “They’re stretched way too thin to add another task to their calendar, so we take it upon ourselves instead.”

Not Just for Pittsburgh

Before developing BigBurgh.com, Firth, Lagana, and the HCEF studied the websites and apps available to the homeless in other cities and discovered only five, including Link-SF, which was launched by a tech company in San Francisco as part of a community benefits agreement when it located in a historically impoverished neighborhood. Such agreements give companies benefits like tax breaks and require the companies to give back to the community, either in volunteer hours, as was the case with the company that designed Link-SF, or other ways. Those apps, however, typically rely on self-reporting by agencies and services, rather than implementing a program of regular outreach for updates. While BigBurgh.com itself is colorful and splashy, during its development, more emphasis was placed on what Lagana terms the less glamorous “back office” aspect, which ensures that it provides the most useful information in the most efficient way.

“… an invaluable tool for assisting those who are experiencing homelessness, as well as providing a resource for law enforcement and social services personnel.”

“Thanks to cloud platforms, it’s now relatively easy and inexpensive to develop high-quality, user-friendly apps,” Firth asserts. “Given a strong enough commitment from interested community and government partners, there’s little reason that a service like BigBurgh.com couldn’t be replicated in other areas of the country with just as much success.”

Government Incubates Creativity and Funds Results

BigBurgh.com has high profile advocates in Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto, who has long made ending homelessness a priority of his administration, and Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald. When Lagana first demonstrated the site for the pair, the excited mayor called in all his staffers to witness the demonstration and has pledged government support to maintain the site once the two-year, philanthropically-funded trial period is completed.

“I challenged other organizations to take on the issue of homelessness in Pittsburgh and Alleghany County,” says Mayor Peduto. “The launch and implementation of this app is an innovative example of HCEF’s leadership in that challenge, and I applaud its ongoing efforts.”

Fitzgerald characterized BigBurgh.com as “an invaluable tool for assisting those who are experiencing homelessness, as well as providing a resource for law enforcement and social services personnel.” Other officials have lined up in support too. Soon-to-retire Allegheny County Superintendent of Police Charles Moffatt has declared that BigBurgh.com would be “a true asset to officers in the field while assisting the homeless.”

Grace Enick, now studying social work at Chatham University and serving as the coordinator of an art program and exhibit that features the work of youth experiencing homelessness, is equally excited and tells everyone she can about BigBurgh.com. “It would be great to see something developed right here in Pittsburgh spread throughout the country,” she says. “It could change a lot more lives.”

BigBurgh.com was designed to be eye-catching and easy-to-use. It includes a colorful dial that lets the user personalize the results by choosing their age range, gender, and whether they are a veteran of the military or part of a family with children.

Resources