Preface

Millions of children and their families across the United States experience the challenges of homelessness every year. Unfortunately, that number continues to grow. Some turn to family and friends, some are served in shelters and by other social services, and some are left to fend for themselves in cars, on the streets, and in tent cities. What started out over three decades ago as local initiatives in response to homelessness have grown and evolved into national priorities, state policies, and municipal bureaucracies. What began as calls for more shelter and more affordable housing have expanded to approaches in communities that include the education, health, childcare, and employment services that are so often needed as part of a family’s journey out of homelessness.

But there is still so much more that needs to be done.

The American Almanac of Family Homelessness is a publication that describes the situations and characteristics of those millions of children and their parents, as well as the efforts made in all 50 states and the District of Columbia to better identify and serve those families. The Almanac is both a tool for and challenge to advocates, service providers, policymakers, funders, and families. It represents the factors that influence and impact family homelessness, as well as the steps that are being implemented and disseminated across the country.

From its establishment in 1990, the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness has been a voice for children, families, and providers to challenge the status quo. We analyze what data is available and identify where more is needed. We question entrenched beliefs and present different points of view, thereby providing a more complete picture of the experience of family homelessness. The Almanac, with its state rankings, data dashboards, ideas for action, and issues exploration, is the embodiment of ICPH’s 25 years of experience and analysis and a resource to connect policy, practice, and research and move each forward.

Leonard N. Stern, Chair

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, President and CEO

Introduction

Family homelessness has challenged the United States for more than three decades. What we know about the impact of homelessness on children and their families has grown tremendously during that time, yet policies and funding priorities still too often overlook the unique needs of homeless families.

The Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH) created the American Almanac of Family Homelessness in 2013 to contribute to the limited body of literature that informs policies directly affecting homeless families. The updated 2015 edition of the Almanac not only compiles the data on family homelessness that is available but also provides the context and analysis necessary to understand the issue. It provides policymakers, government administrators, service providers, advocacy groups, researchers, and concerned citizens with a comprehensive resource that highlights what existing data reveal about homeless families and the programs that serve them—and where gaps exist in knowledge and data collection.

The Almanac begins by introducing ICPH’s inaugural State Family Homelessness Rankings, a resource that evaluates and ranks state performance within two domains: efforts to identify and serve homeless children and youth and the adoption of policies that can prevent homelessness and allow families to regain housing stability. Each domain employs five unique indicators; the results are reported by indicator and as composite education and policy scores, allowing readers to easily compare states and identify areas for improvement.

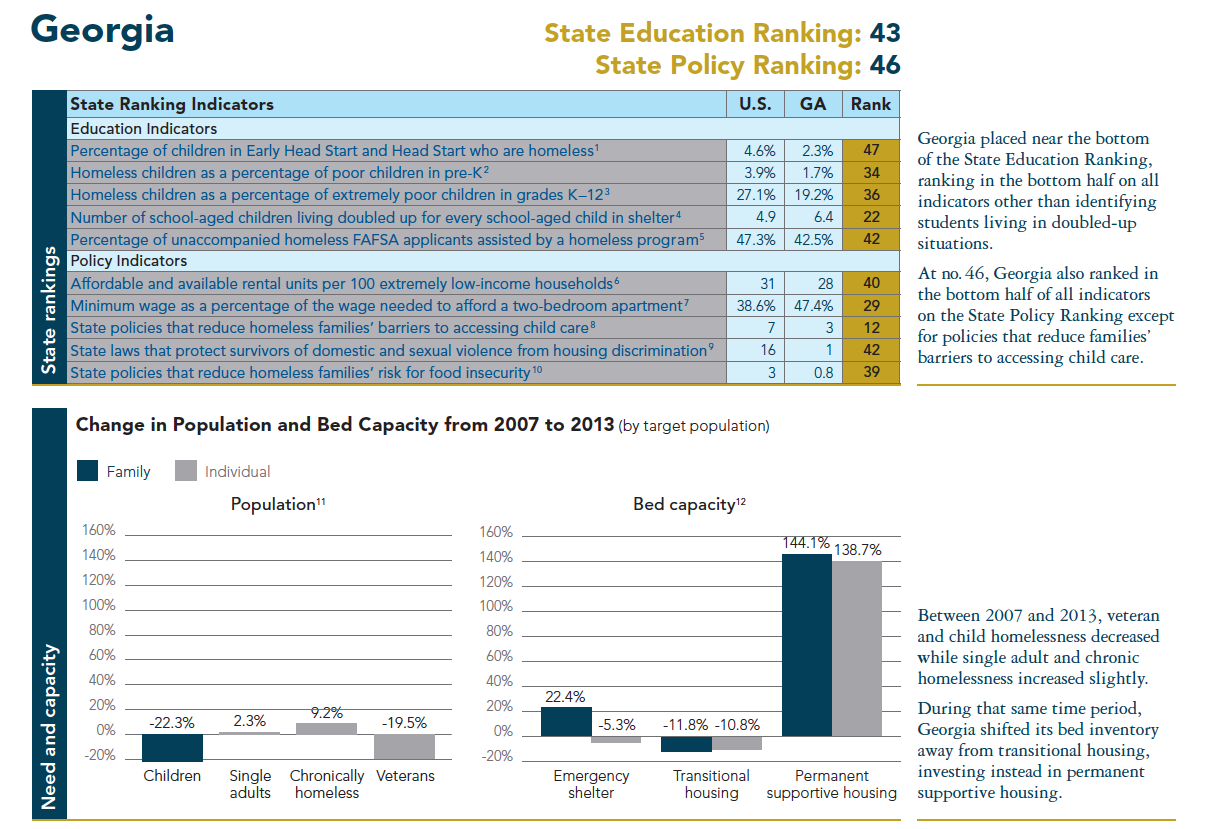

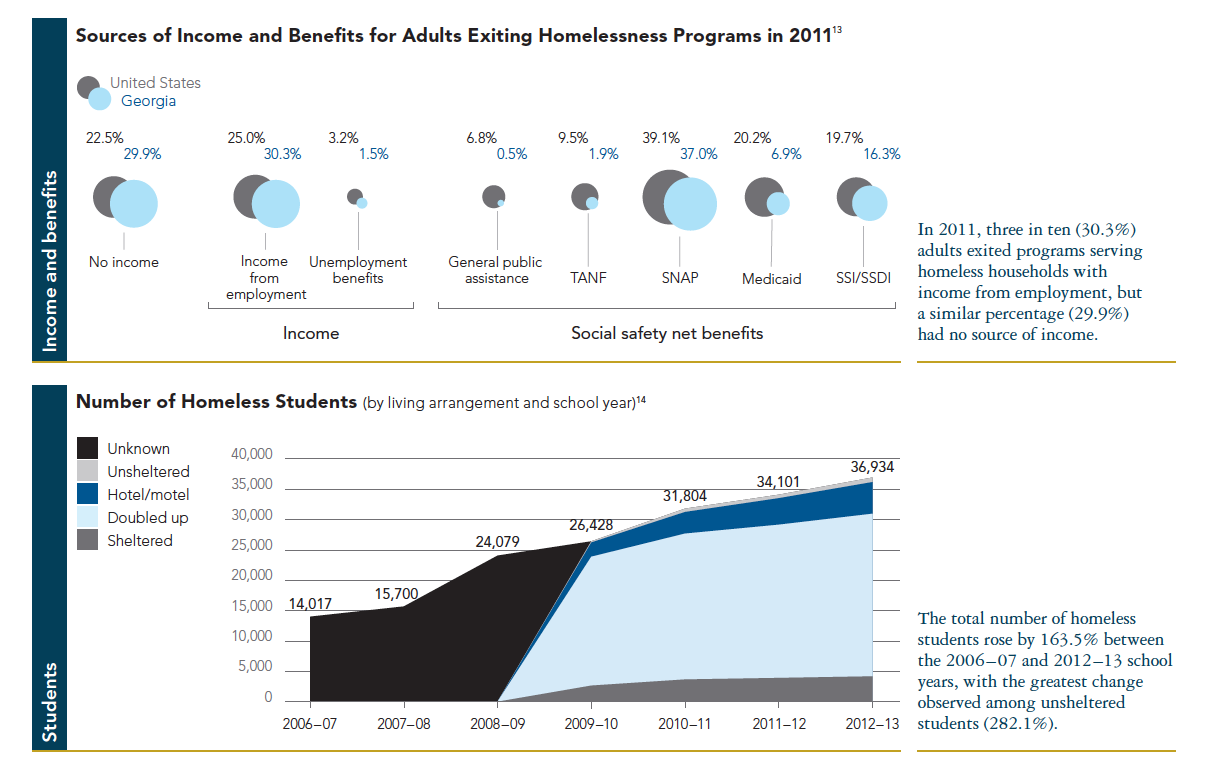

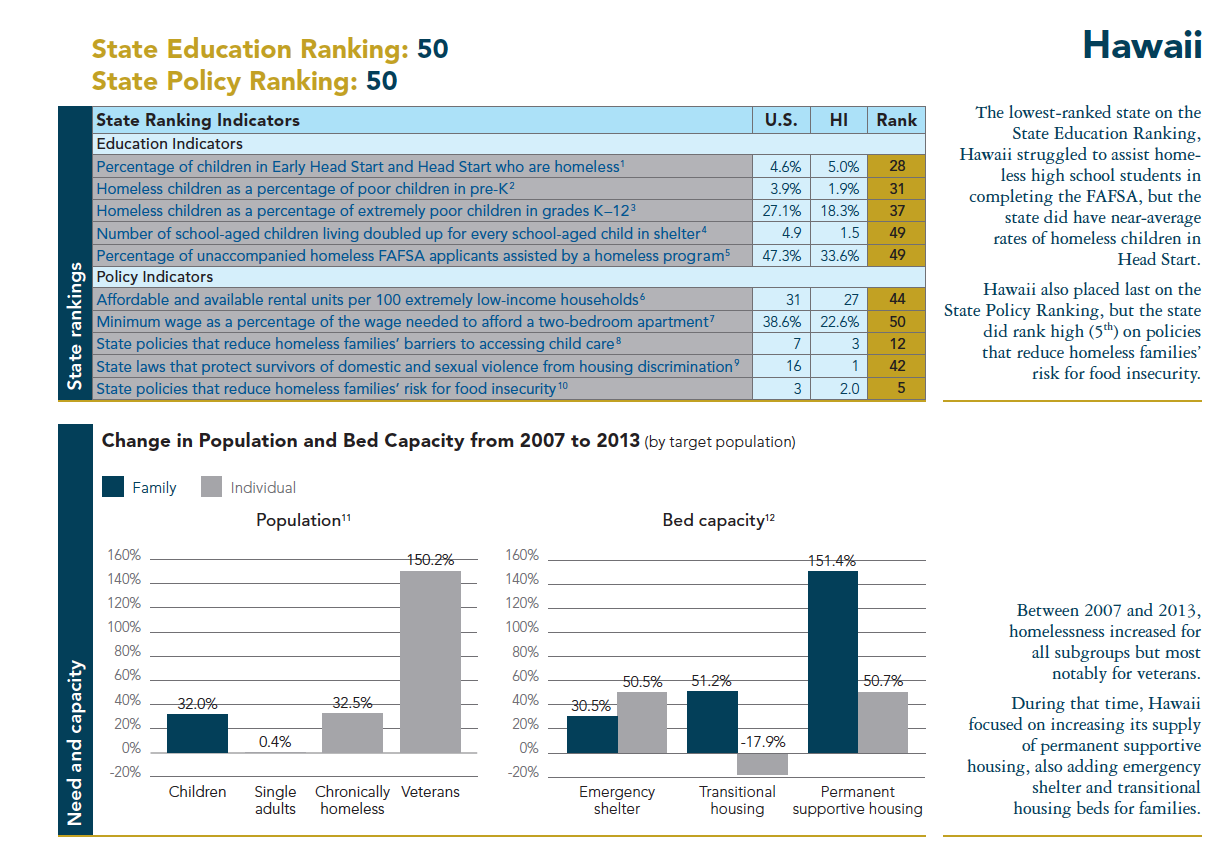

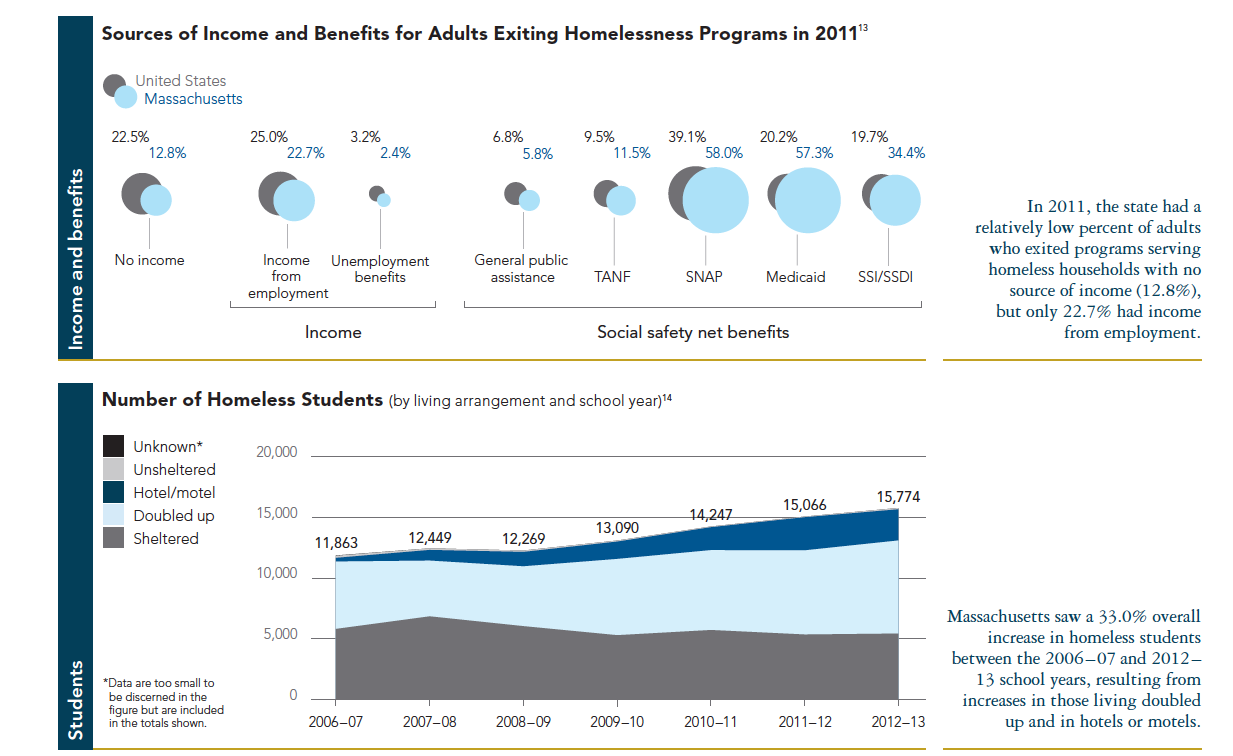

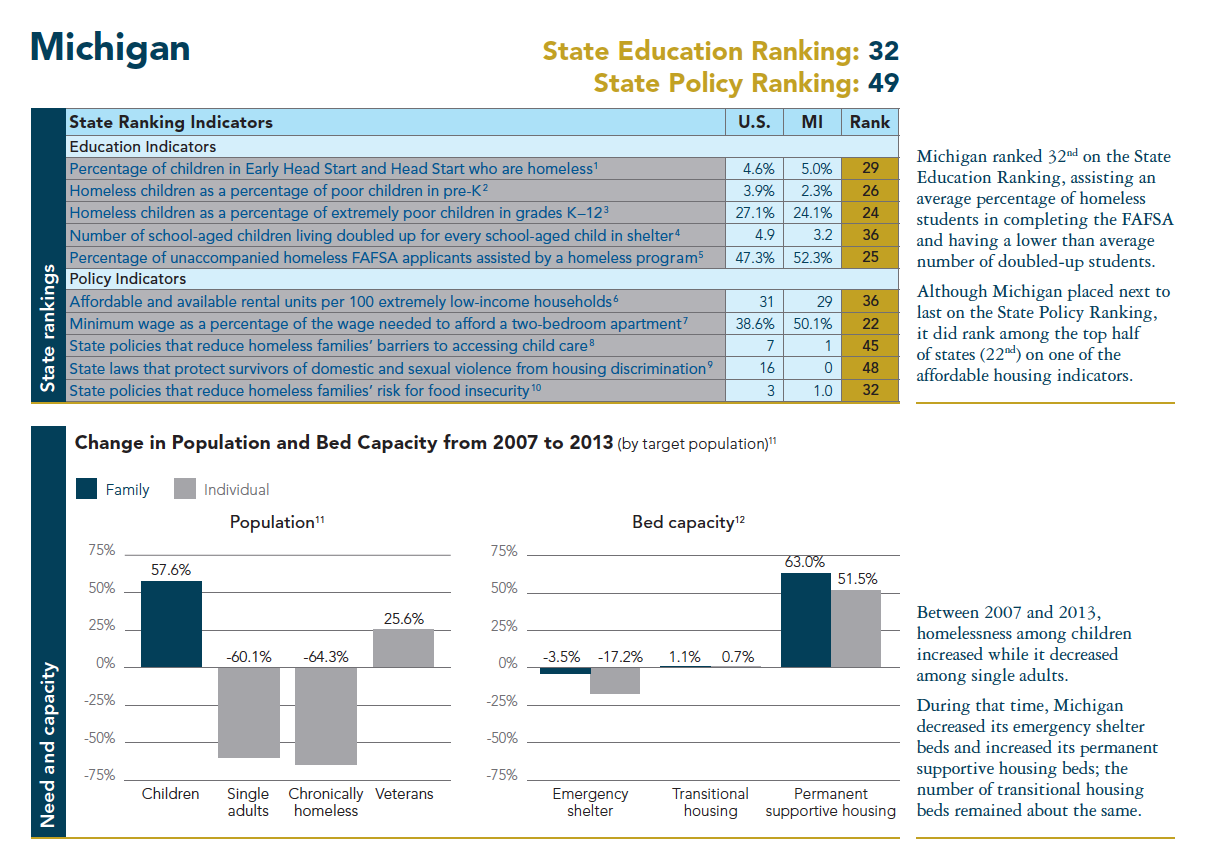

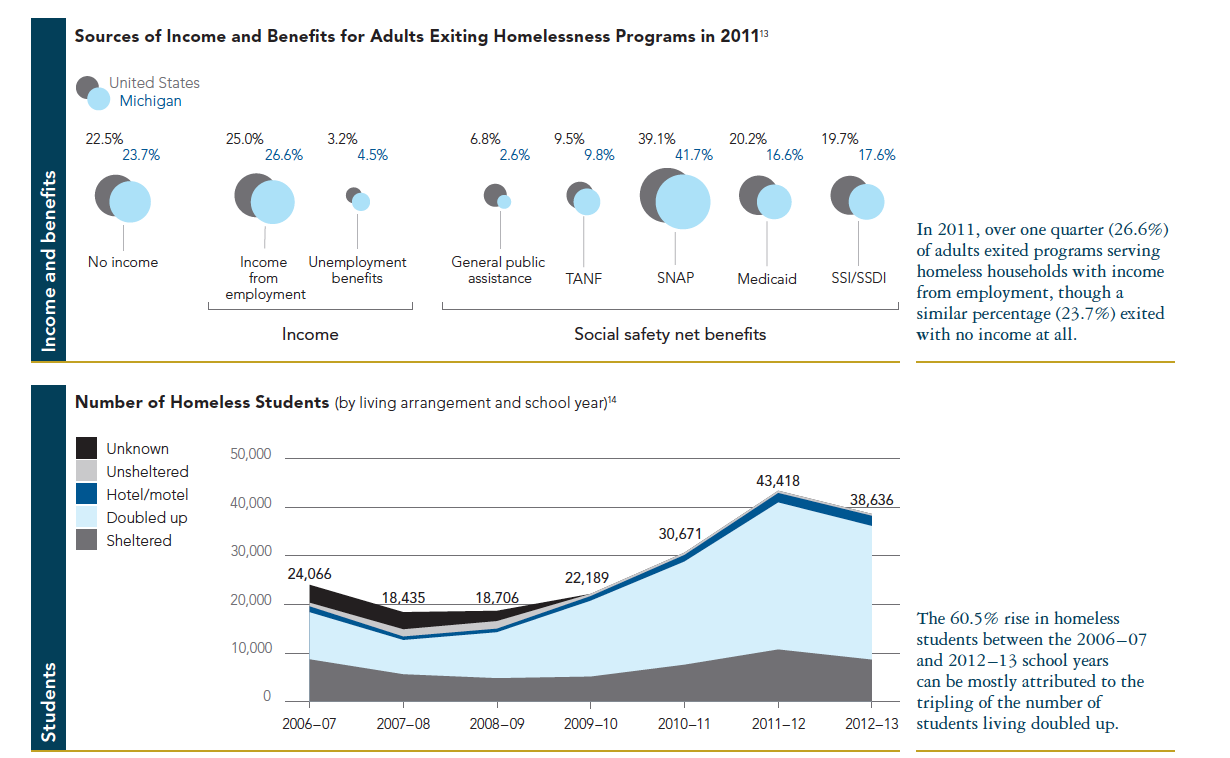

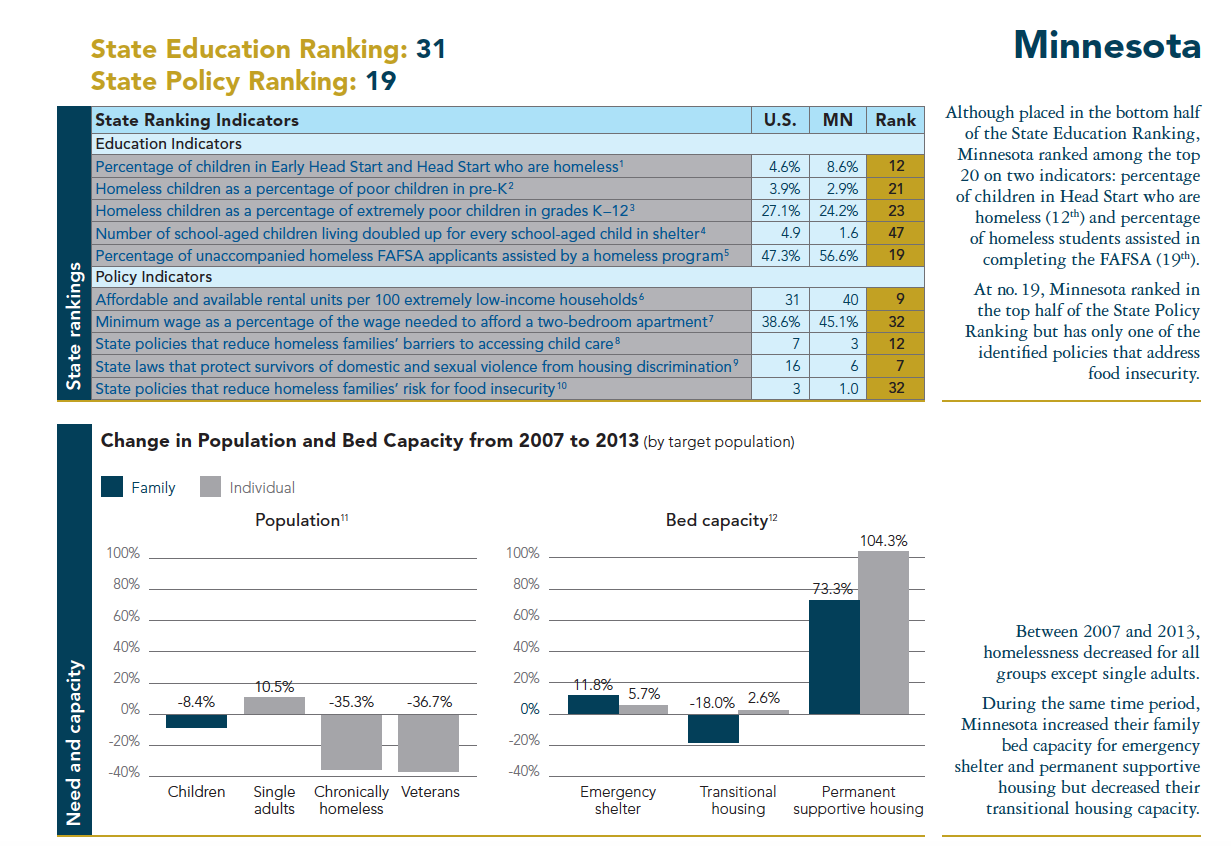

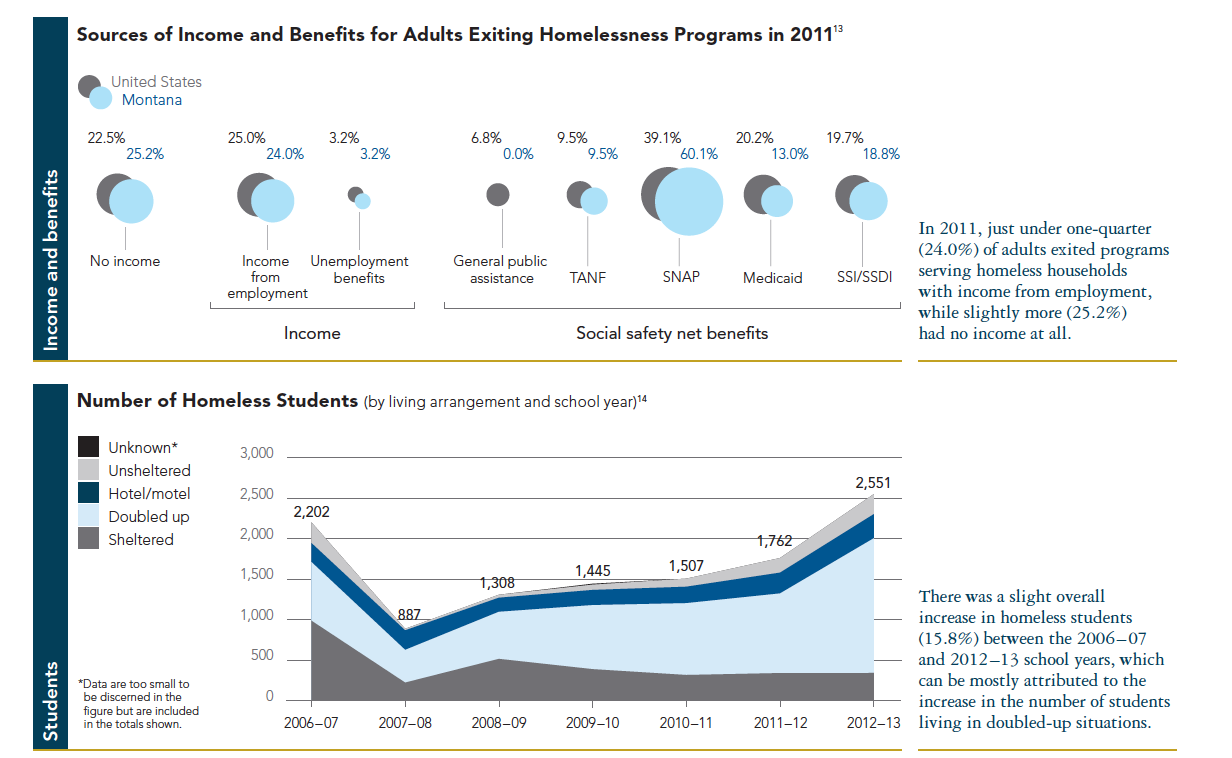

The state rankings are followed by State Dashboards, one for each state and the District of Columbia. These one-page reports—replacing the state-by-state briefs in the 2013 edition—provide a summary table of each state’s placement on the state rankings and highlight easy-to-compare statistics on family homelessness. By showcasing trends and statistics through straightforward graphics, the dashboards supply readers with the data they need to assess the status of family homelessness and related policies in each state.

New to the 2015 edition of the Almanac is a section detailing ICPH’s Ideas for Action. These policy priorities and recommendations are focused on three key areas of family homelessness: education for homeless children, policies supporting homeless families, and research and targeted assistance. They contain cost-effective and practical steps that each state can implement even without federal action. These policy changes would help to mitigate the effects of homelessness by increasing educational opportunities for homeless children, protecting domestic violence survivors, bolstering parents’ ability to support their families, and ensuring that research and funding is targeted to effective programs and the most vulnerable populations.

Issue by Issue, the final part of the Almanac, contains six thematic sections that explore the challenges that homeless families face and options for interventions. These articles provide in-depth discussions of key topics relevant to the study of family homelessness. Starting with demographics and trends in child and family homelessness, the remaining sections cover the macroeconomic causes of family homelessness; the effects of homelessness on families and children; education for homeless children; federal homelessness policy and types of homelessness housing models; and the role of social safety net benefits in preventing and resolving homelessness.

The Almanac demonstrates that the needs of homeless children and families are too varied and complex to ever be effectively addressed with a one-size-fits-all approach. As shown within these pages, strong efforts are being made in many communities but more are needed at the local, state, and federal levels to effectively target, tailor, and fund the services that children and families need to move onto a path of independence.

State Rankings

Examining Practices and Policies to Prevent and Reduce Family Homelessness

Our understanding of family homelessness today has been informed by the experiences of millions of families in all 50 states and thousands of communities over the last three decades. State governments, and the county and municipal agencies that implement policies and programs locally, have an important role to play in addressing the housing, social, financial, and educational instability that families experiencing homelessness face in the country’s diverse rural, suburban, and urban communities.

Plans for ending family homelessness must be as multifaceted as families’ needs in order to be successful. While effective national policy is important, state leaders and policymakers are in a unique position to create a statewide framework that supports many of the necessary solutions. Communities need a variety of tools in their solutions tool-box in order to not only meet the basic and immediate needs of children and families, but to also confront the underlying causes of homelessness that can impact multiple generations within families.

With the need for a multi-pronged approach in mind, ICPH developed the State Family Homelessness Rankings, which comprise two distinct ranking systems. The first measures and compares the efforts that states are making to educate homeless children in their communities, and the second looks at the state and local policies in place to assist homeless families, covering issues related to housing, child care, domestic violence, and food insecurity. Each indicator was chosen not just because of its impact on homeless families, but also because it is a factor that states have the power to change. For example, state and local agencies can independently improve efforts to identify students living doubled up, pass laws protecting survivors of domestic violence from housing discrimination, and implement policies to increase access to child care subsidies.

This first part of the Almanac, the State Family Homelessness Rankings, presents in detail how the rankings were constructed, as well as ICPH’s findings and analysis of each indicator. The top-ranked states on each indicator are also highlighted to provide additional context and offer examples for other states seeking to improve their own programs and policies. While each state’s rankings are listed here, specific data for each state is also included in the second part of the Almanac, State Dashboards.

State Family Homelessness Rankings

Examining Practices and Policies to Prevent and Reduce Family Homelessness

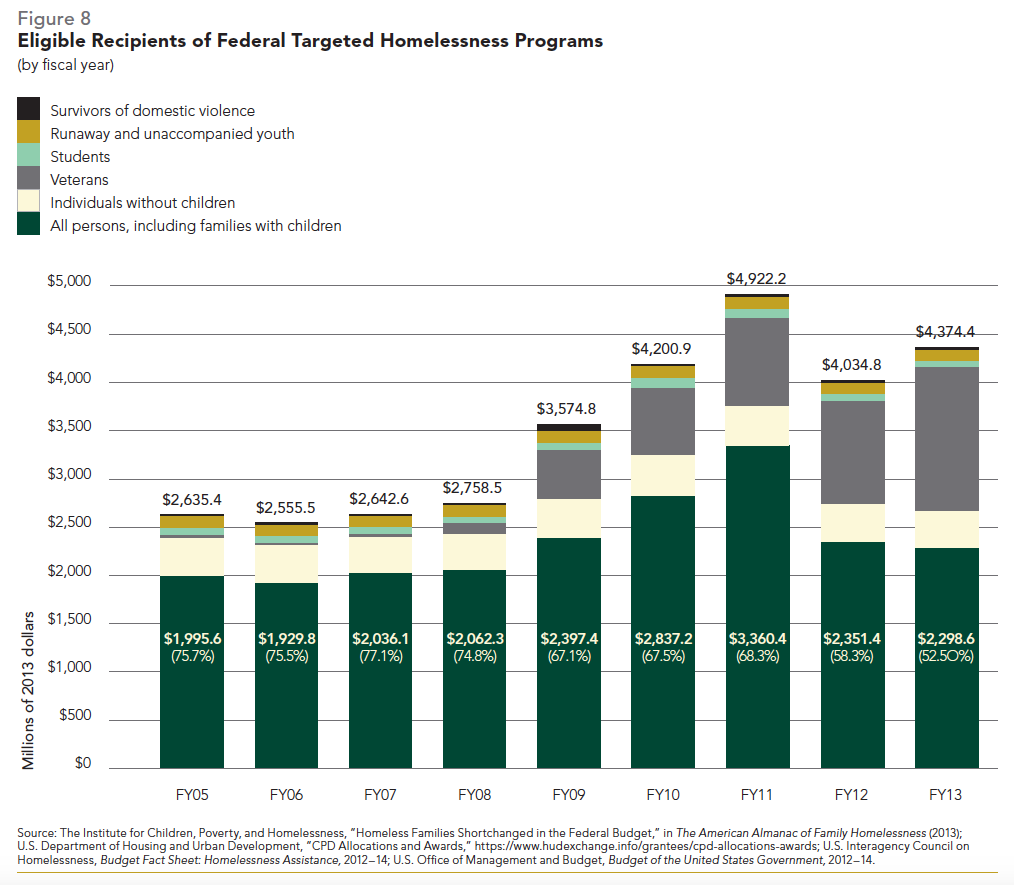

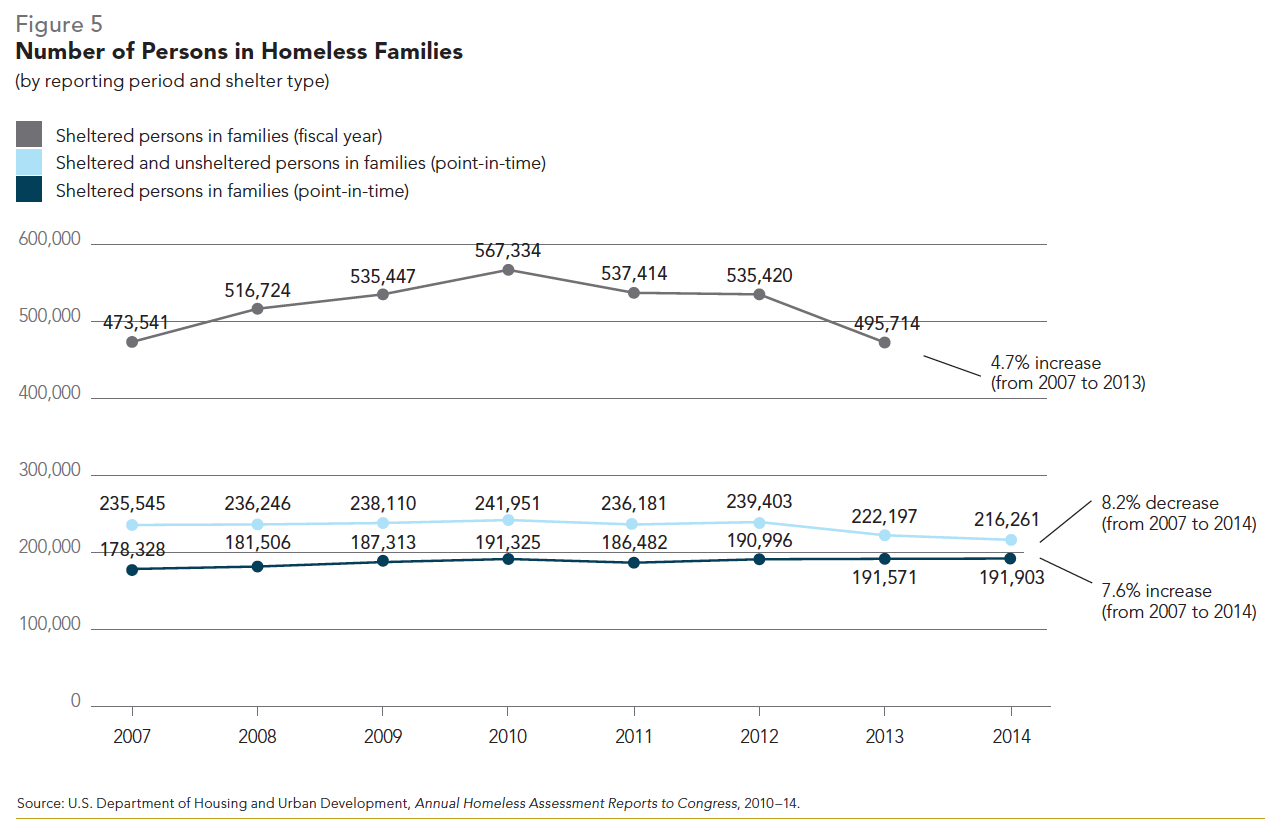

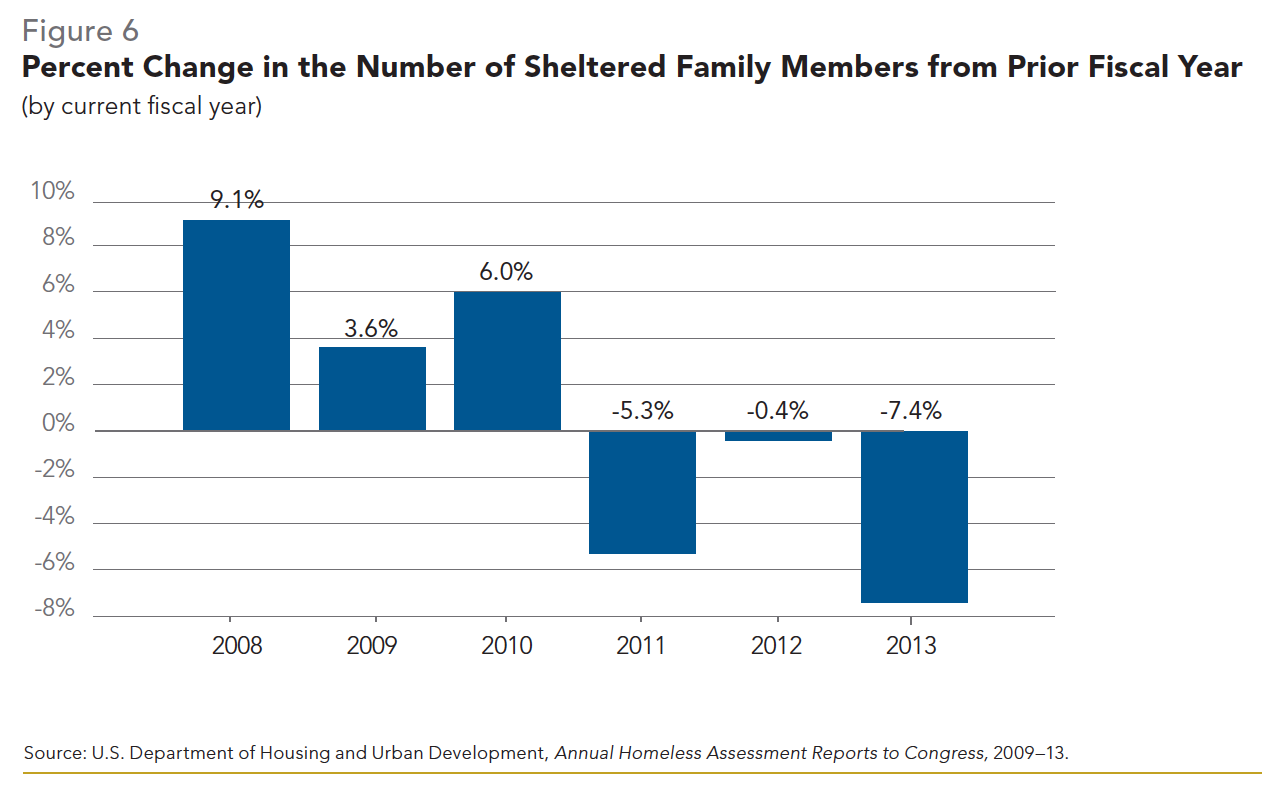

The first national plan for ending homelessness was released in 2010 and set the goals of ending chronic and veteran homelessness by 2015 and ending homelessness among families, children, and youth by 2020. Since the plan’s release, the national spotlight has focused more on the former goal than the latter.1 Subsequently, homelessness decreased among veterans and chronically homeless single adults. However, between 2009 and 2014, the number of family members who access shelter— over 190,000 on a single night—did not.2

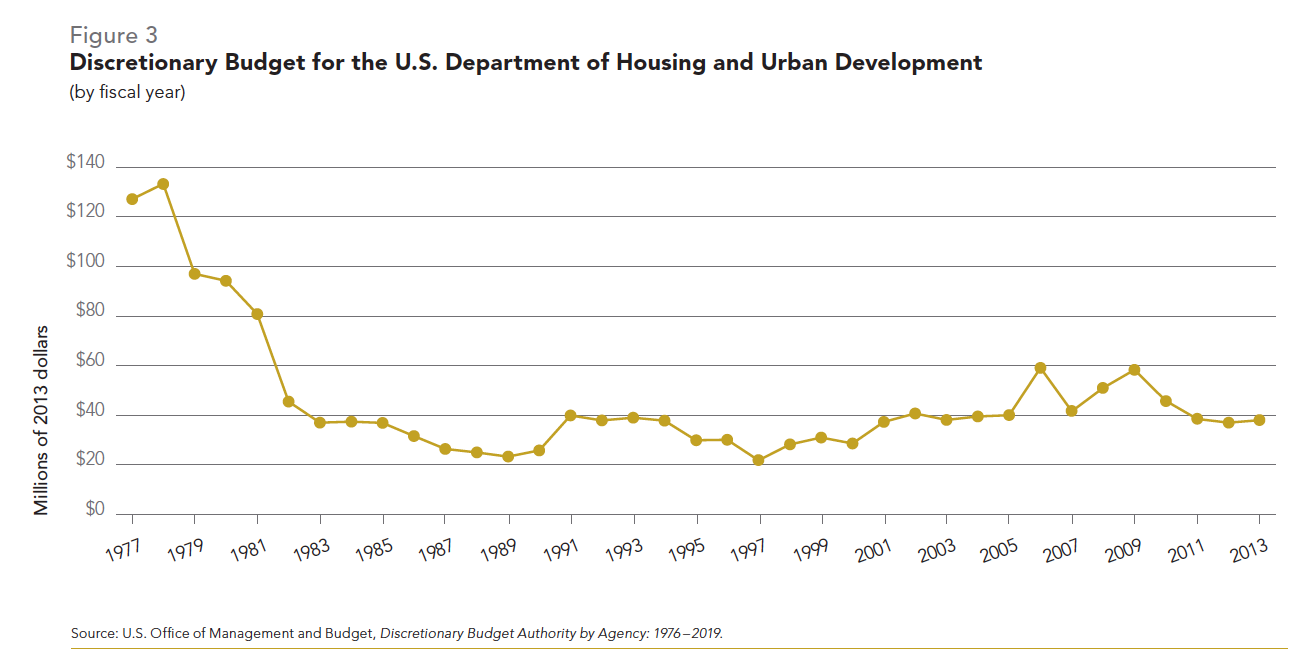

Although federal funding and leadership is required, state and local investments are also essential to alleviate family homelessness. Crucial federal legislation safeguards the educational rights of homeless students, but it is ultimately up to state and local educators to identify and serve homeless children. Federal funding for low-income housing has plummeted since the 1980s, so state and local governments must contend with creating and preserving affordable housing. Within the scope of federal guidelines, states shape how safety net programs are administered and can reduce access barriers for homeless families seeking assistance. These are only a few examples of the critical roles states play in ending family homelessness.

To assess and raise awareness of the services and policies necessary to address family homelessness, the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH) has developed the State Family Homelessness Rankings, based on a unique set of indicators to compare states’ efforts and to reveal how well states are doing in meeting homeless families’ and children’s needs.

ICPH created the State Family Homelessness Rankings by first examining existing cross-state and -country indices of family and child well-being, including the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s KIDS COUNT Data Book, the Foundation for Child Development’s Child Well-being Index, the National Center on Family Homelessness’ America’s Youngest Outcasts, and, at the international level, indices developed by the United Nations Development Programme.3 Common to many of these indices are measures of poverty. While poverty is a multifaceted cause of homelessness and homelessness exacerbates its effects, poverty measures alone are too broad in scope to address the immediate goal of ending family homelessness. In examining poverty, it is also easy to blame macroeconomic forces or place the responsibility to act on individual families themselves. With this in mind, ICPH aimed to develop indicators that are connected to the larger issue of poverty but directly relate to an action that can be taken at the state level to prevent or reduce family homelessness. A state’s ranking can therefore be improved upon with effective policies and collaboration.

State Education Ranking

Children are the invisible victims of homelessness. Children experiencing housing instability are at greater risk for poor academic outcomes than stably housed children, but they often are not identified and are left disconnected from the services necessary for them to thrive. For these vulnerable children, access to high-quality educational resources and support is perhaps the surest way to prevent intergenerational poverty and homelessness. The five education indicators provide a measure of how well homeless children of all ages are being identified and connected to services, from early education for the youngest homeless children to financial assistance for youth attending college.

State Policy Ranking

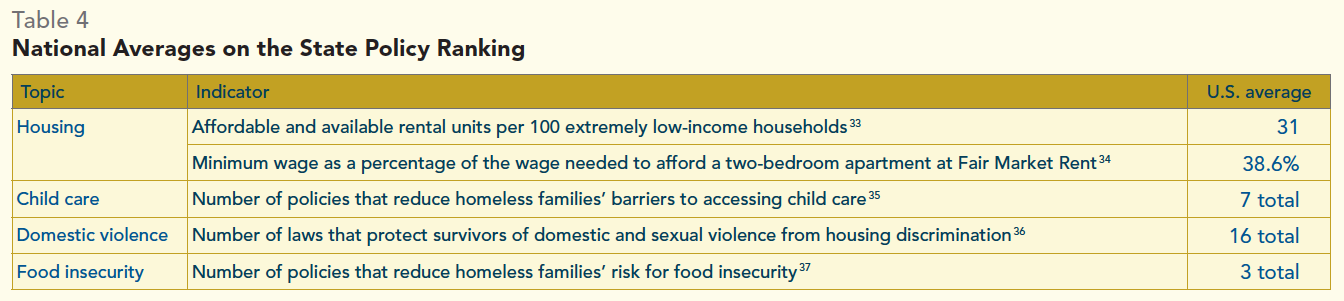

State and local policies must support homeless families’ paths to self-sufficiency rather than impede them. The first two policy indicators reflect the need for affordable housing, including the lack of available rental units for families with extremely low incomes and the low purchasing power of the minimum wage. The remaining indicators reflect policies each state has in place to improve the lives of homeless families and to prevent episodes of homelessness. They target three key issues related to family homelessness: lack of accessible child care, discrimination against survivors of domestic violence, and food insecurity.

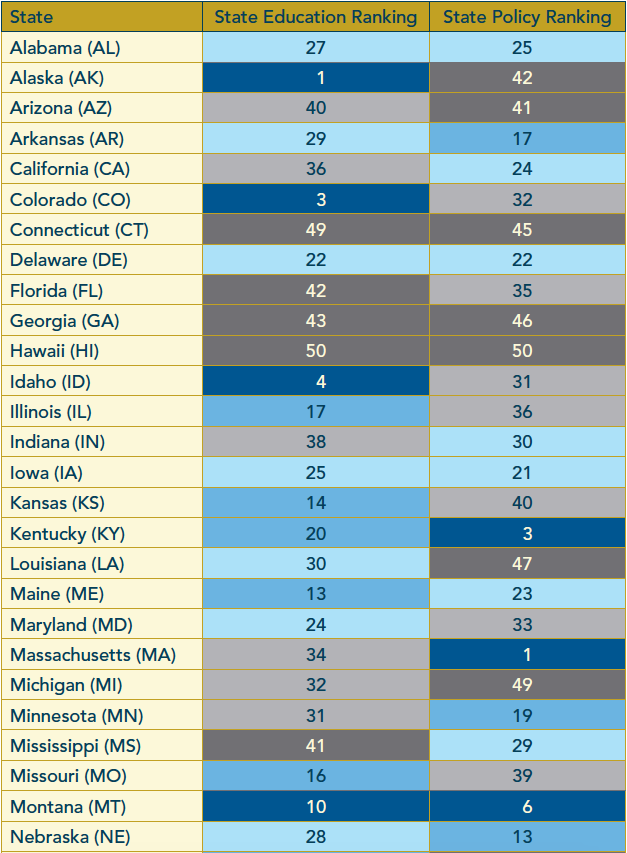

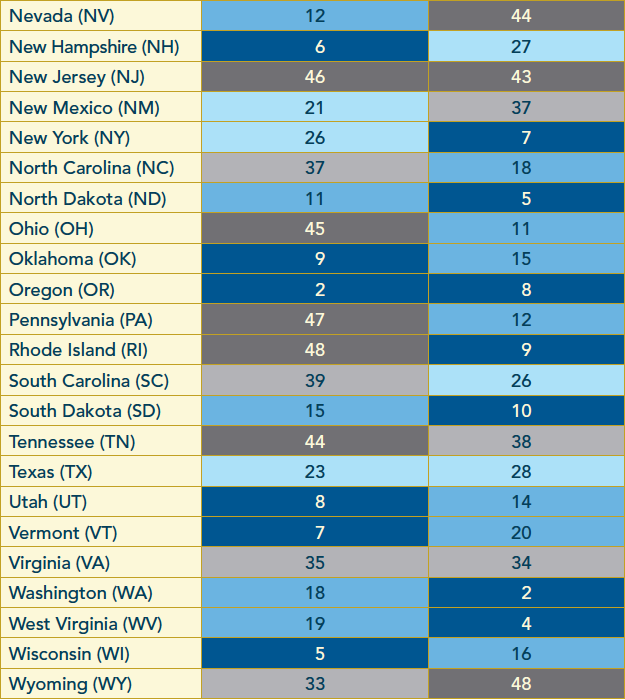

The State Family Homelessness Rankings compare each state across ten indicators, which are analyzed and grouped thematically, creating two separate rankings: the State Education Ranking and the State Policy Ranking.4

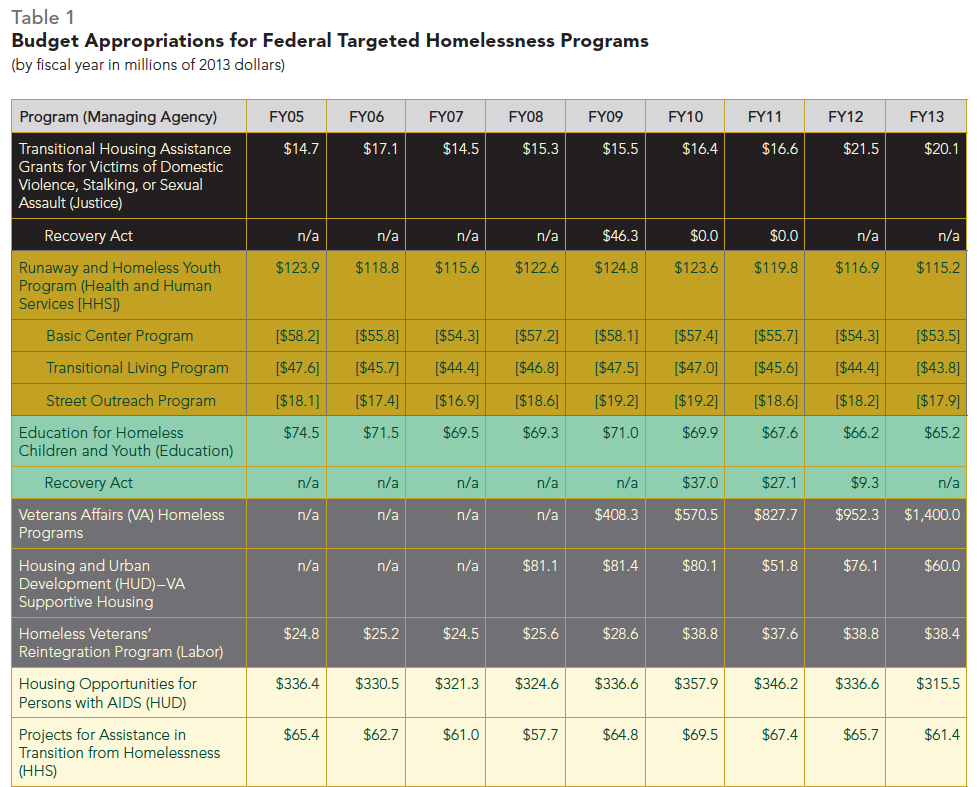

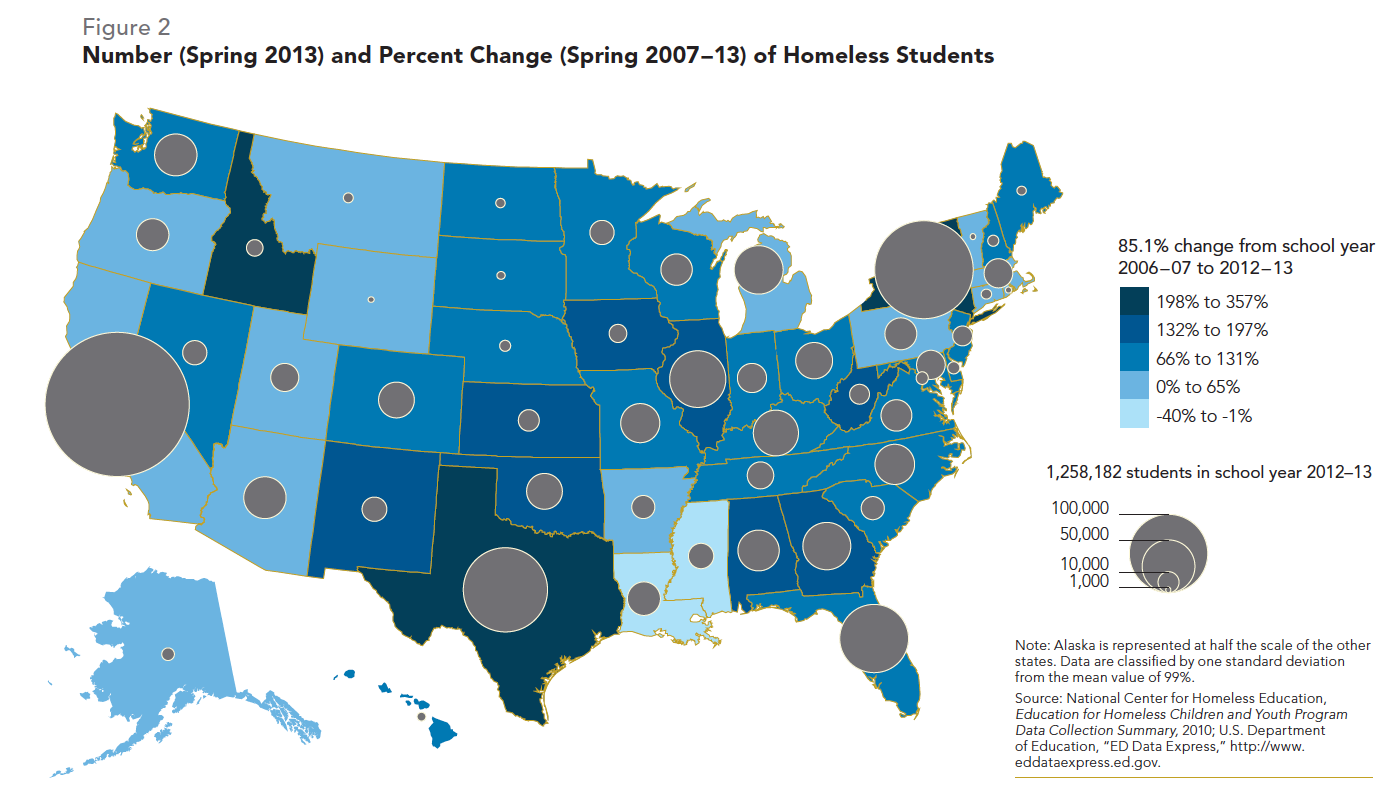

States are graded from 1 to 50 (top to bottom) on the two rankings, with 1 representing the highest-scoring state on a given measure and 50 representing the lowest. By ranking states, ICPH hopes to not simply differentiate between those with robust and weak policies but also to encourage state and local leaders to discover what other states are doing well—and how they are doing it. While what is working in one state may not work in another, states atop the rankings provide examples of promising practices (Table 1).

State Education Ranking

Meeting the Educational Needs of Homeless Children

While homelessness can impact many aspects of a child’s life, including health and socio-emotional development, the experience can also be detrimental to their education. Students experiencing homelessness may have difficulty attending school regularly, and bring with them to the classroom a variety of worries and distractions that can make learning difficult. Therefore, it is vital not only that homeless students are identified, but also that the services and resources that they need are available to help mitigate the negative impacts that housing instability can have on their educational experiences.

The ICPH State Education Ranking examines how effective states are in identifying and assisting students experiencing homelessness, from birth through college. Conventional wisdom would suggest that the state with the lowest number or percentage of homeless students should be ranked highest. However, that number tells only part of the story. A low number may reflect that a state truly has few homeless families, or it might indicate that not enough effort has been made to identify homeless students. Given this, the State Education Ranking uses indicators that provide more context and better approximate the efforts that are being made in each state to address homeless children’s educational needs. In addition, the number of states that are above or below the national average for each of the indicators is provided as a basis for comparison.

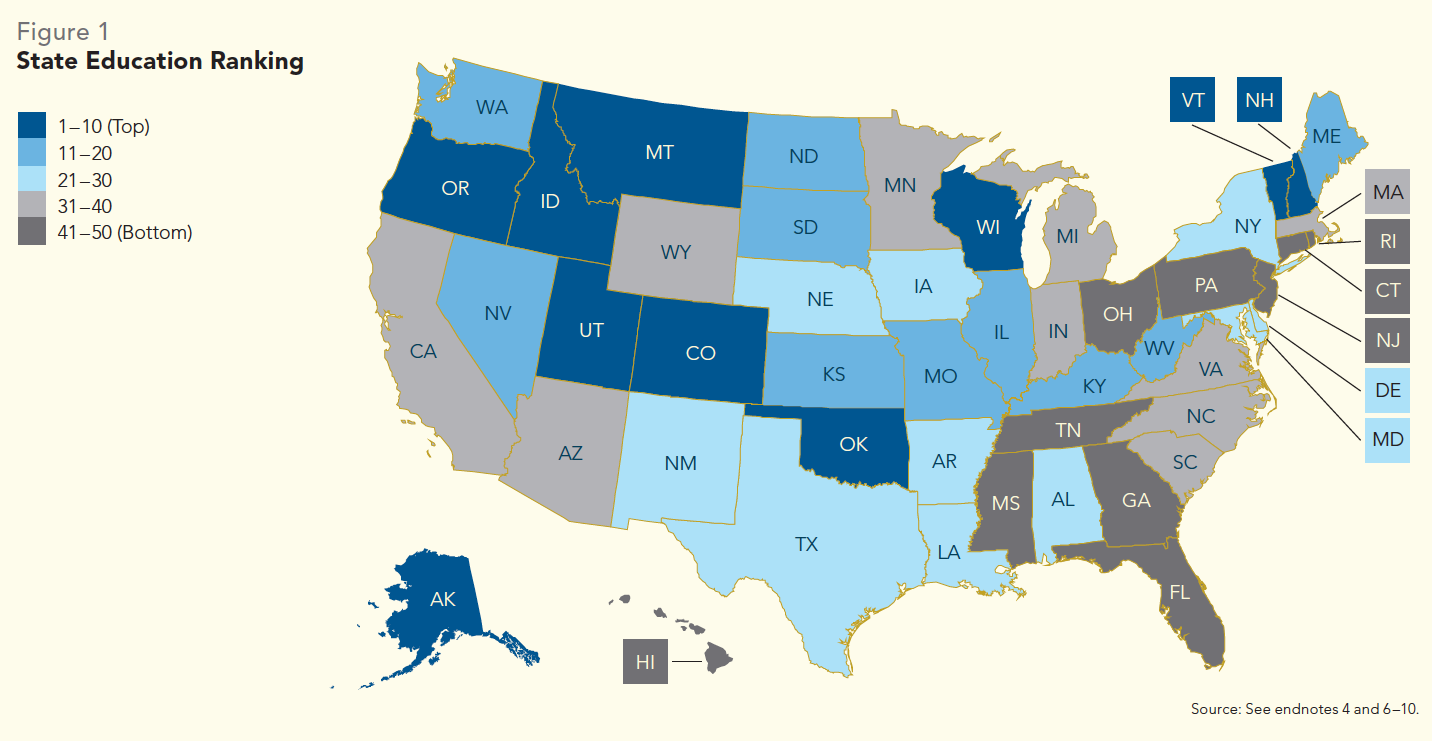

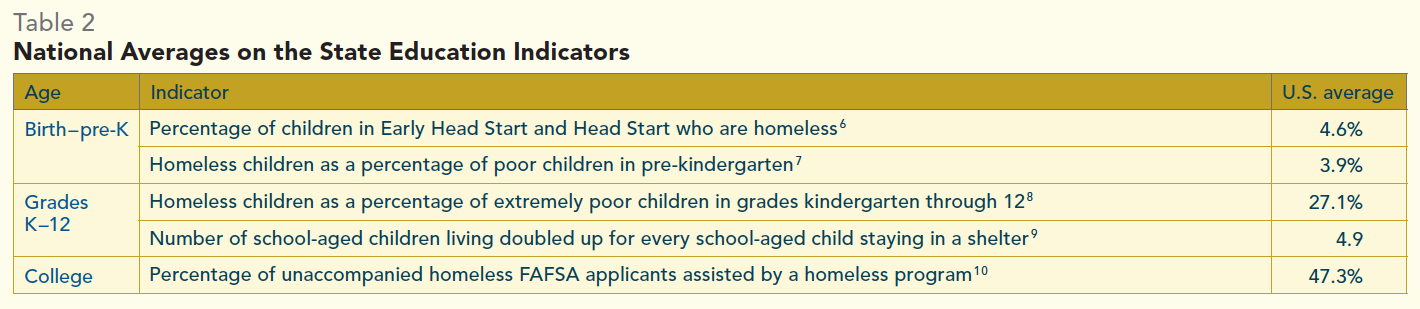

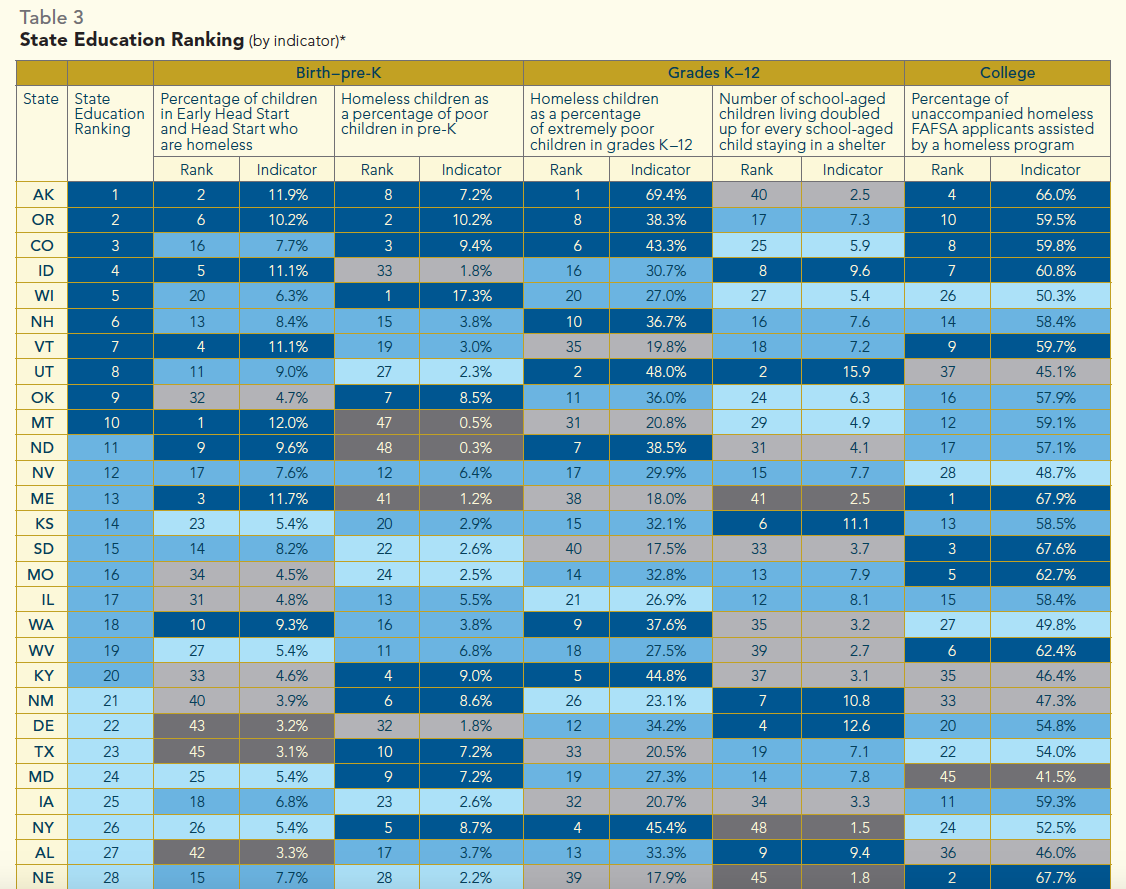

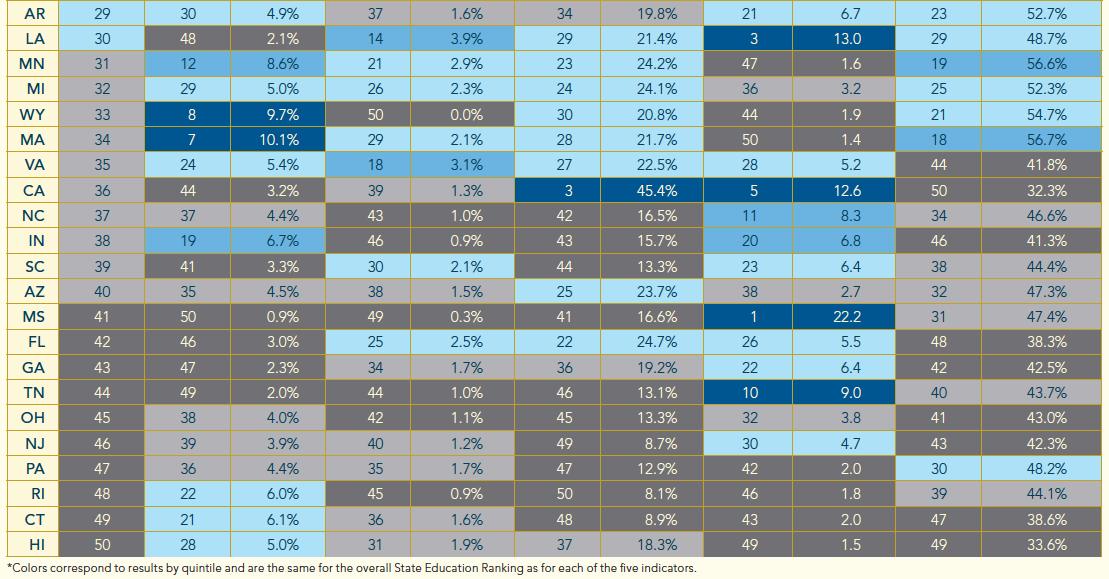

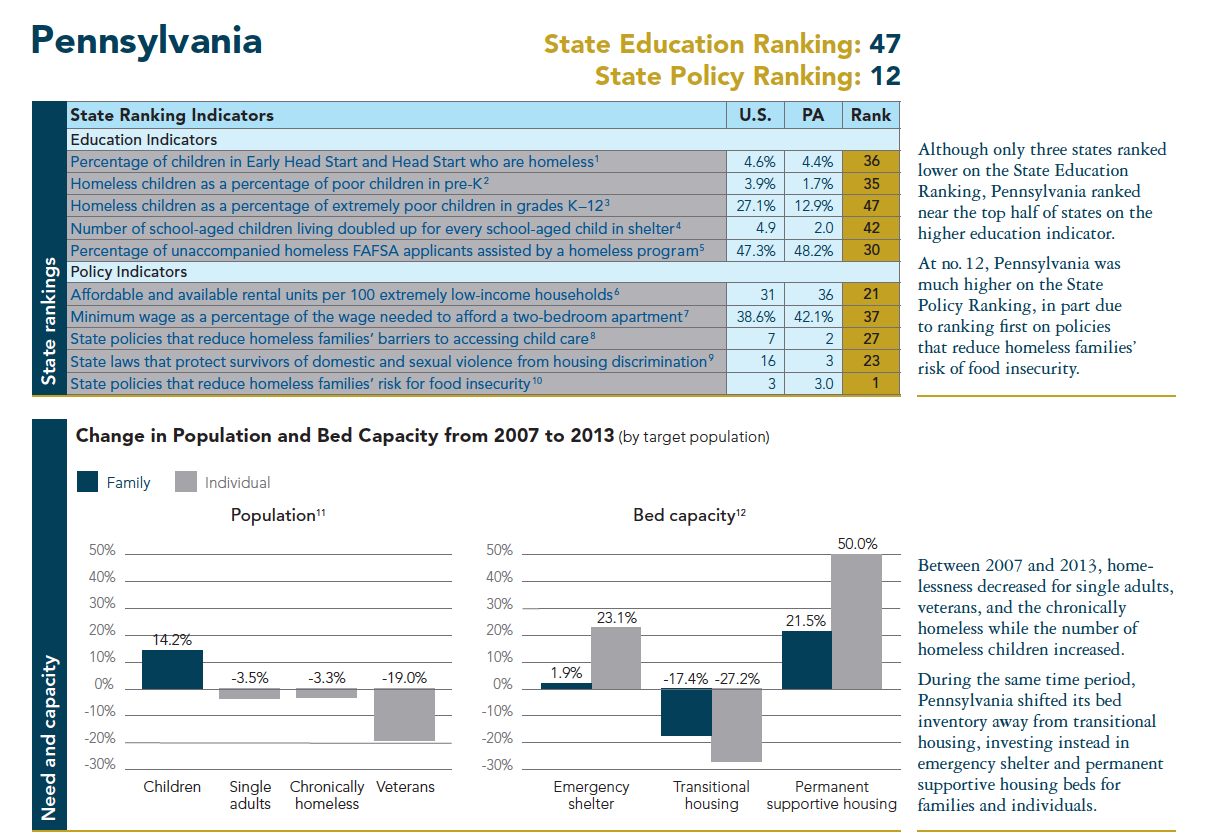

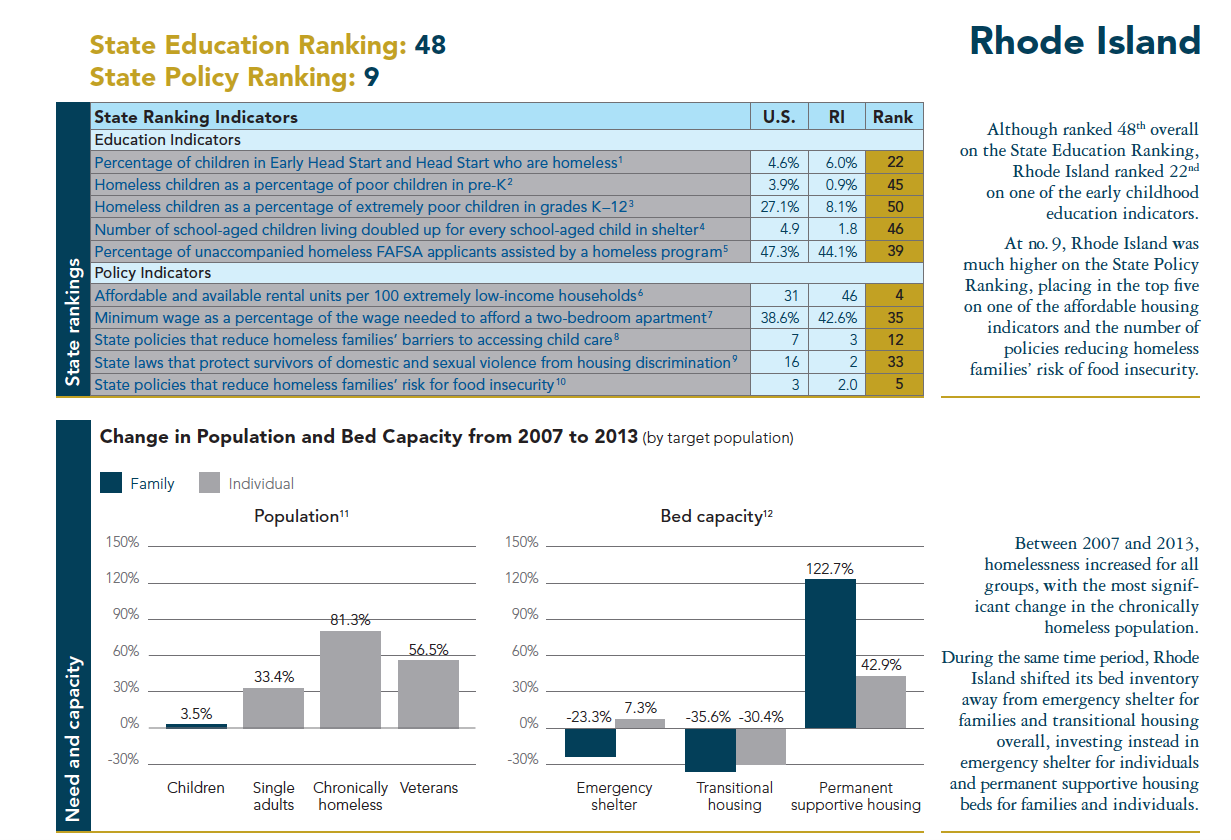

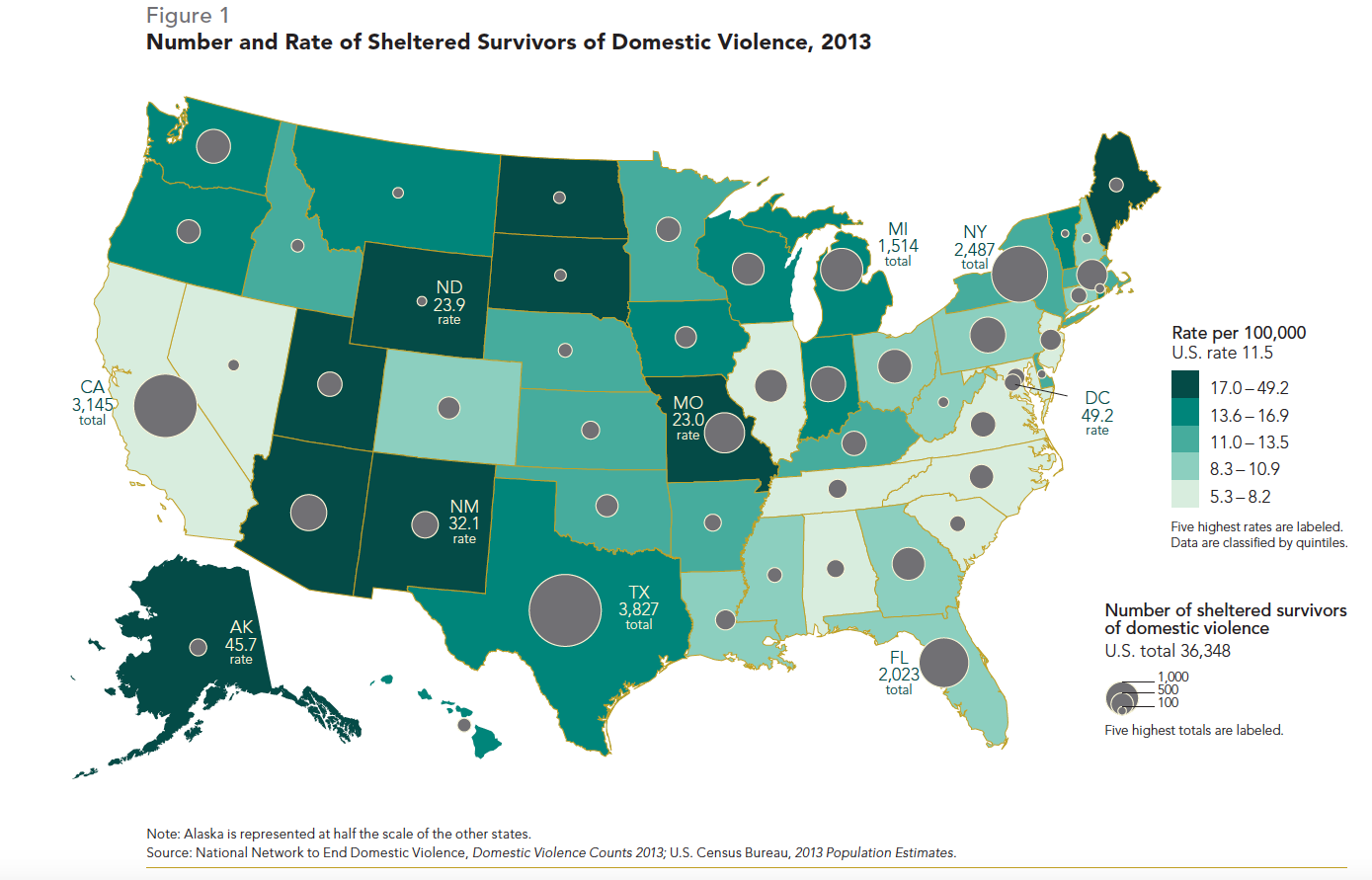

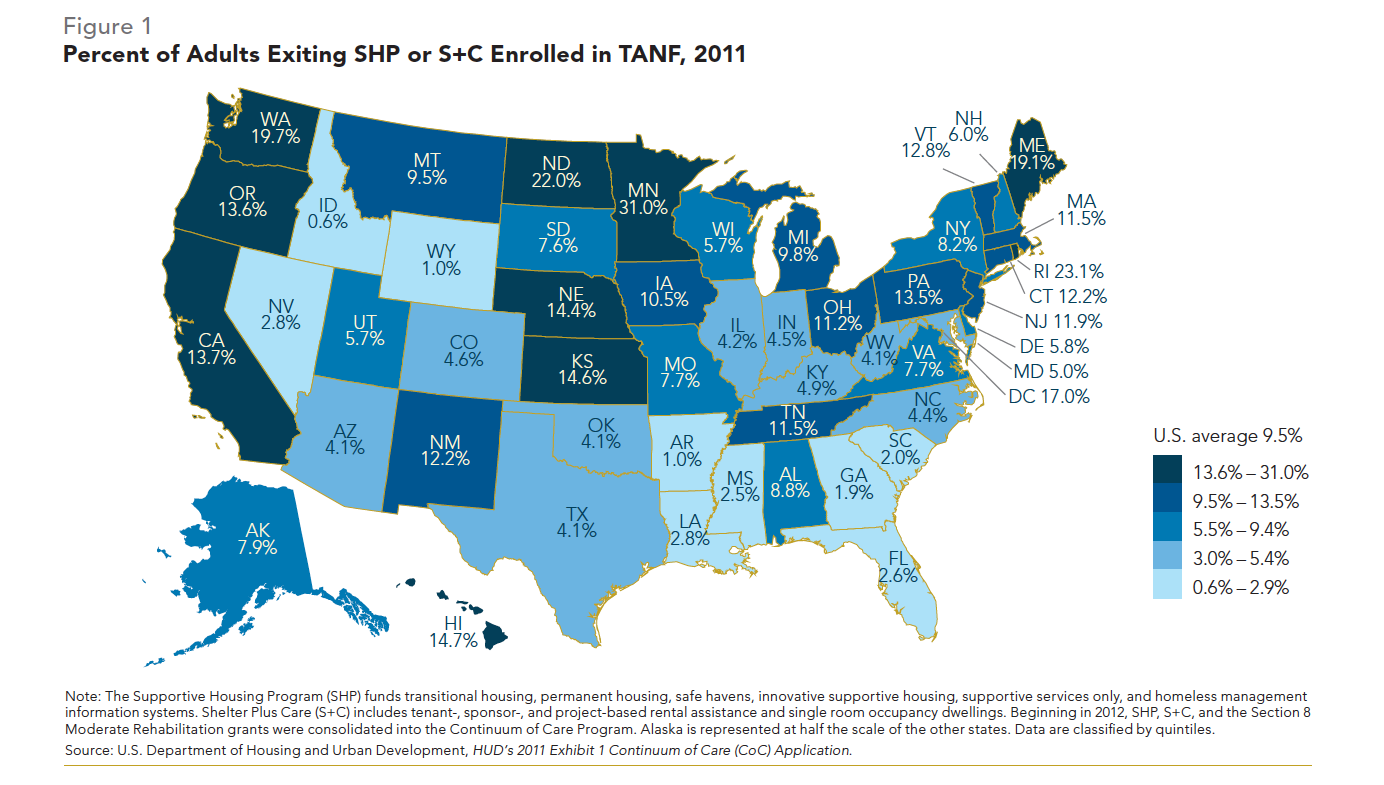

The State Education Ranking measures, shown in Table 3, indicate that the majority of states have difficulty identifying homeless children of all ages. As a result, many children are not accessing the educational services that can prevent the intergenerational cycle of homelessness. Aside from last-ranked Hawaii, the states ranked lowest on the combined five education indicators are located in the southeastern, mid-Atlantic, and northeastern regions of the country, with New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Connecticut ranked 46th through 49th (Figure 1). The states most successful at identifying and enrolling homeless children tend to be in the westernmost sections of the country—Alaska, Oregon, and Colorado are the three highest ranking states—with the exception of Vermont and New Hampshire, both ranked in the top ten.5

Educating Homeless Children from Birth to Preschool

According to statistics from the U.S. Census Bureau, there were 24 million children under the age of six in the United States in 2013. While one quarter (25%) lived below the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), or $19,530 for a family of three, it is not known how many of these young children experienced housing instability by living doubled up with another household, in a hotel or motel, in a shelter, or on the streets.11 Economically disadvantaged children, including those experiencing homelessness, benefit from high-quality early childhood education; the percent of homeless children who access these programs, however, is also unknown. Given these limitations, the State Education Ranking uses two indicators as surrogates for the number of young homeless children in a state: the percent who access Head Start and the percent enrolled in pre-K.

Low-income children who participate in high-quality early childhood education programs are less likely to repeat a grade or be placed in special education, graduate from high school at higher rates, and are more likely to be employed and have higher earnings later in life.12 High-quality early education programs are particularly critical for young children experiencing homelessness, who are more at risk than their housed peers for developmental delays and behavioral, emotional, and mental health issues.

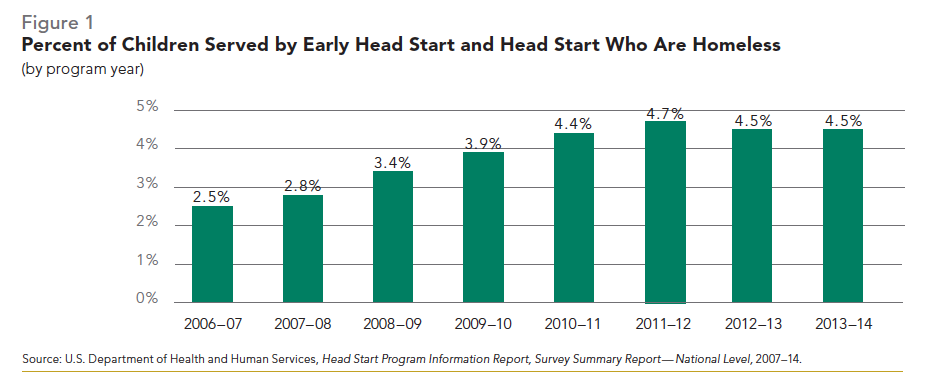

Although the total number of homeless children under the age of six is unclear, 4.6% or 50,992 out of 1.1 million children who participated in Early Head Start (EHS), for children zero to three years old, and Head Start (HS), for children ages three to five, were homeless during the 2012–13 program year. Low-income families participating in these federally funded early childhood development programs also have access to supportive social services to address education, health care, nutrition, parenting, and, for families experiencing homelessness, housing needs. With the passage of the Improving Head Start for School Readiness Act of 2007, all homeless children were made automatically eligible for EHS and HS programs, and states were directed to identify and prioritize homeless children for enrollment.13

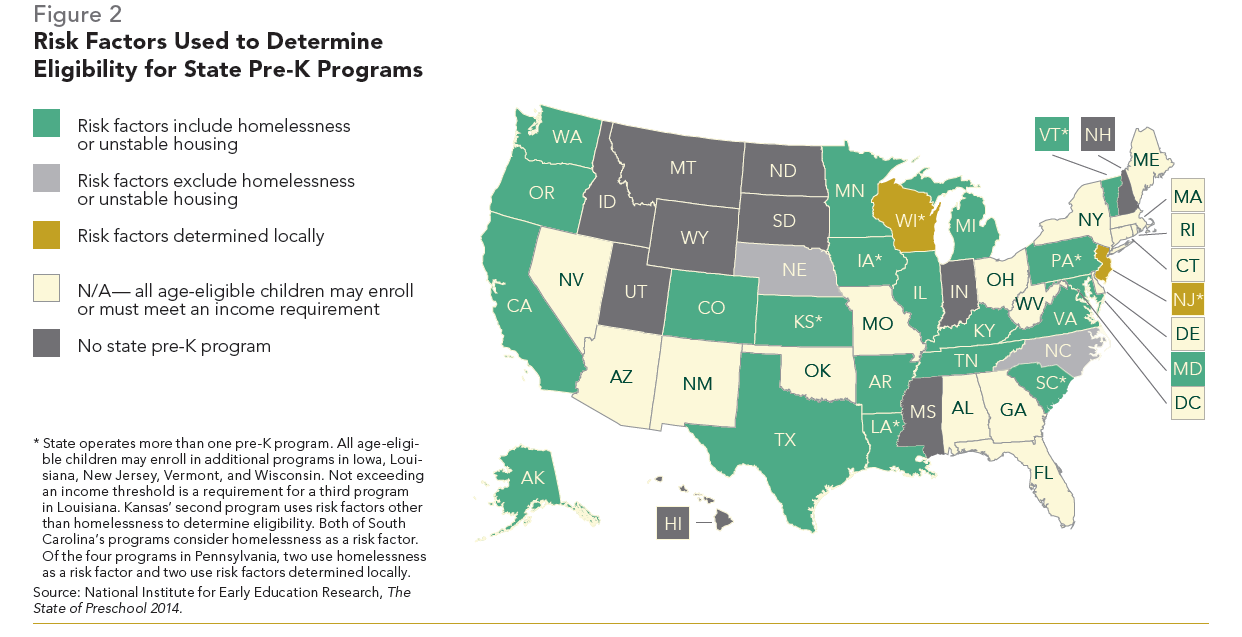

In addition to Head Start, pre-K programs offer another early education setting in which homeless children can get the tools they need to be ready for school.

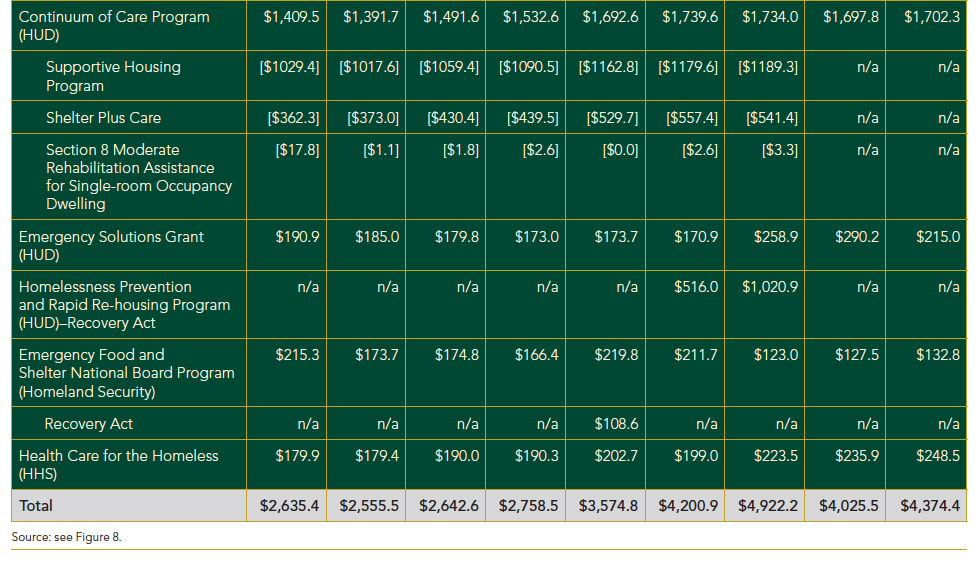

However, only 2.9% or 37,598 out of 1.3 million children ages three to five who attended a pre-K program were homeless during the 2012–13 school year, a rate less than that of children in kindergarten and first grade (3.1% and 3.1%, respectively). Given that the incidence of homelessness is greatest among children under six and that the risk and rate of homelessness decrease as children grow older, the low percent of homeless children among pre-K students compared with other grades suggests that many homeless children are not enrolled in public pre-K.14

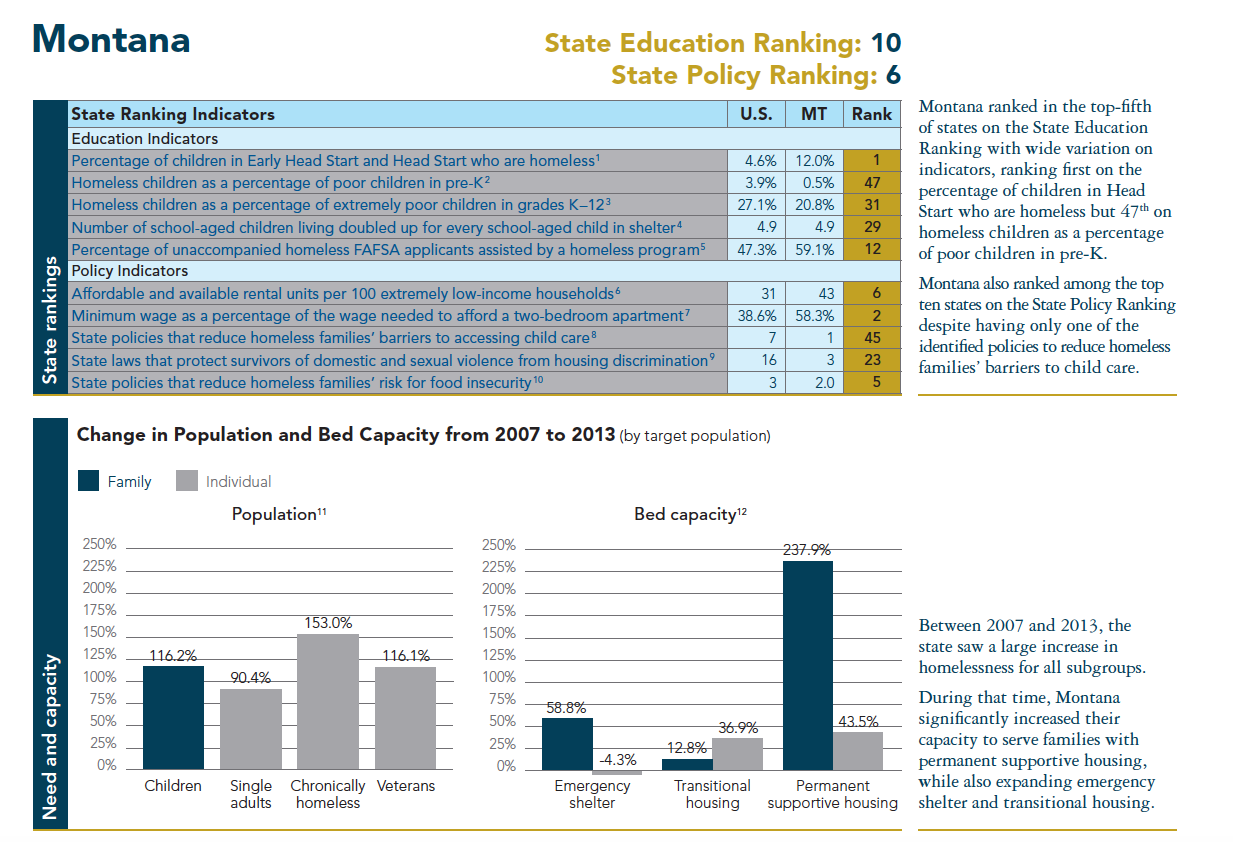

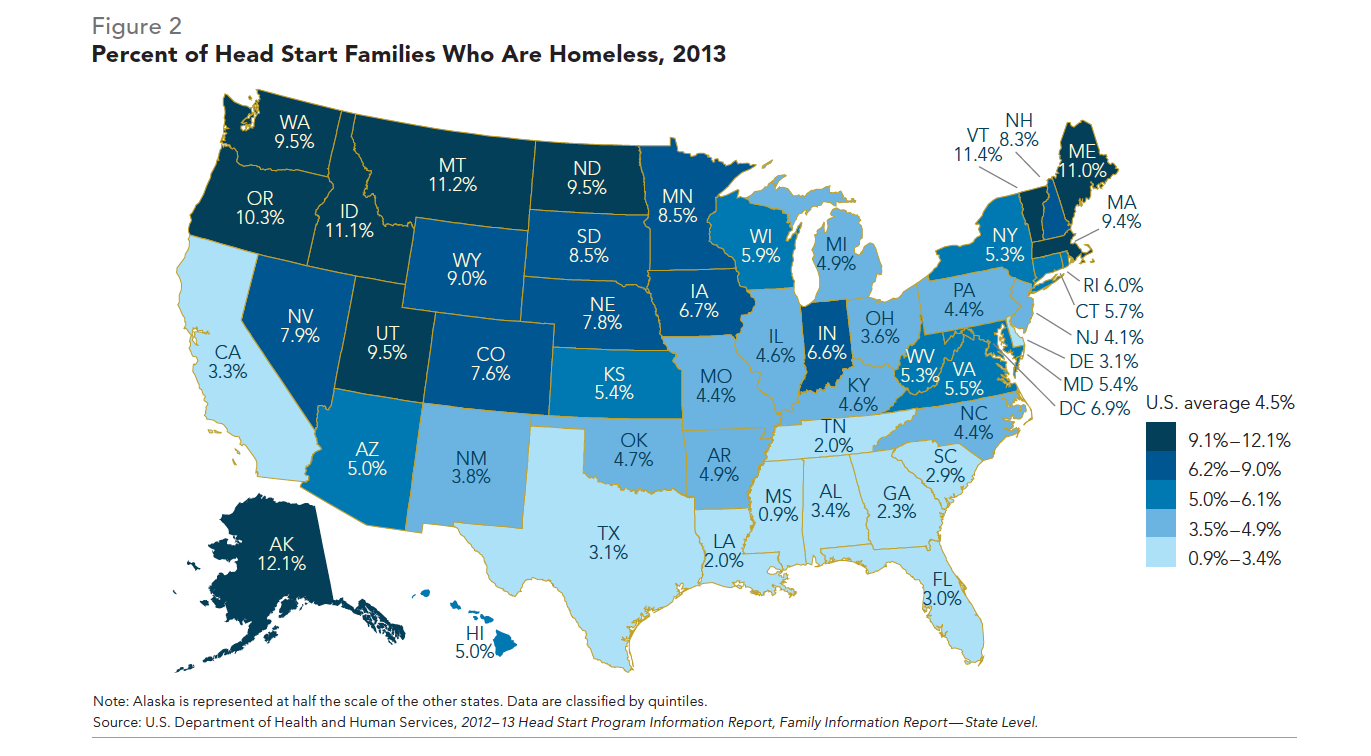

Comparing states on the first education indicator, the State Education Ranking demonstrates that the percent of all children enrolled in either EHS or HS who were homeless varied significantly in 2012–13, ranging from a low of 0.9% in Mississippi to a high of 12.0% in Montana (Example 1). In 33 states, homeless children’s enrollment exceeded the national rate of 4.6%. Northwestern states, including Alaska (11.9%), Idaho (11.1%) and Oregon (10.2%), as well as those in northern New England, such as Maine (11.7%), Vermont (11.1%), and Massachusetts (10.1%), generally enrolled higher rates of homeless children in EHS or HS. The lowest rates were observed across the southeast in Mississippi (0.9%), Tennessee (2.0%), Louisiana (2.1%), Georgia (2.3%), and Florida (3.0%).16 For a detailed discussion of EHS and HS, including barriers to enrolling homeless children, see Issue 6: Mainstream Social Safety Net Programs.

Example 1 Montana’s Head Start

In Montana, 12.0% (or 657) of the 5,472 children enrolled in Head Start during the 2012–13 program year were homeless, the highest rate of any state that year. Although 38 states served more total children in Head Start than Montana, only 25 states enrolled more homeless children in the program.

During the 2012–13 program year, Montana had 29 Head Start programs: nine Early Head Start, 20 Head Start, and no migrant and seasonal Head Start program. These programs served 564 homeless families, 190 of which (or 33.7%) acquired housing during the year, about the same as the national rate of 33.5%. As in most states, the number of homeless families enrolled in Head Start has increased in Montana since the passage of the Improving Head Start for School Readiness Act of 2007. Since the 2007–08 program year, the number of homeless families served by Head Start in Montana has risen 38.2%. While that percent increase is less than half the national average (80.2%), Montana has been improving on an already strong foundation, having had, at 8.2%, the fourth highest percentage of homeless Head Start students of any state during the 2007–08 program year.15

To assess how states are faring on the second education indicator—facilitating access to pre-K—the State Education Ranking compares the number of homeless children with the number of poor children attending pre-K. The numbers of homeless children and poor children are compared with each other, rather than with all children, in order to control for the effects of poverty in a particular state; greater proportions of poor children could be the reason why higher percentages of homeless children are enrolled in pre-K. Nationwide, 3.9% of all poor children enrolled in pre-K also experienced homelessness during the 2012–13 school year. Only 14 states had rates that surpassed the national average, with the percentage ranging from a high of 17.3% in Wisconsin to a low of 0.0% in Wyoming (Example 2).

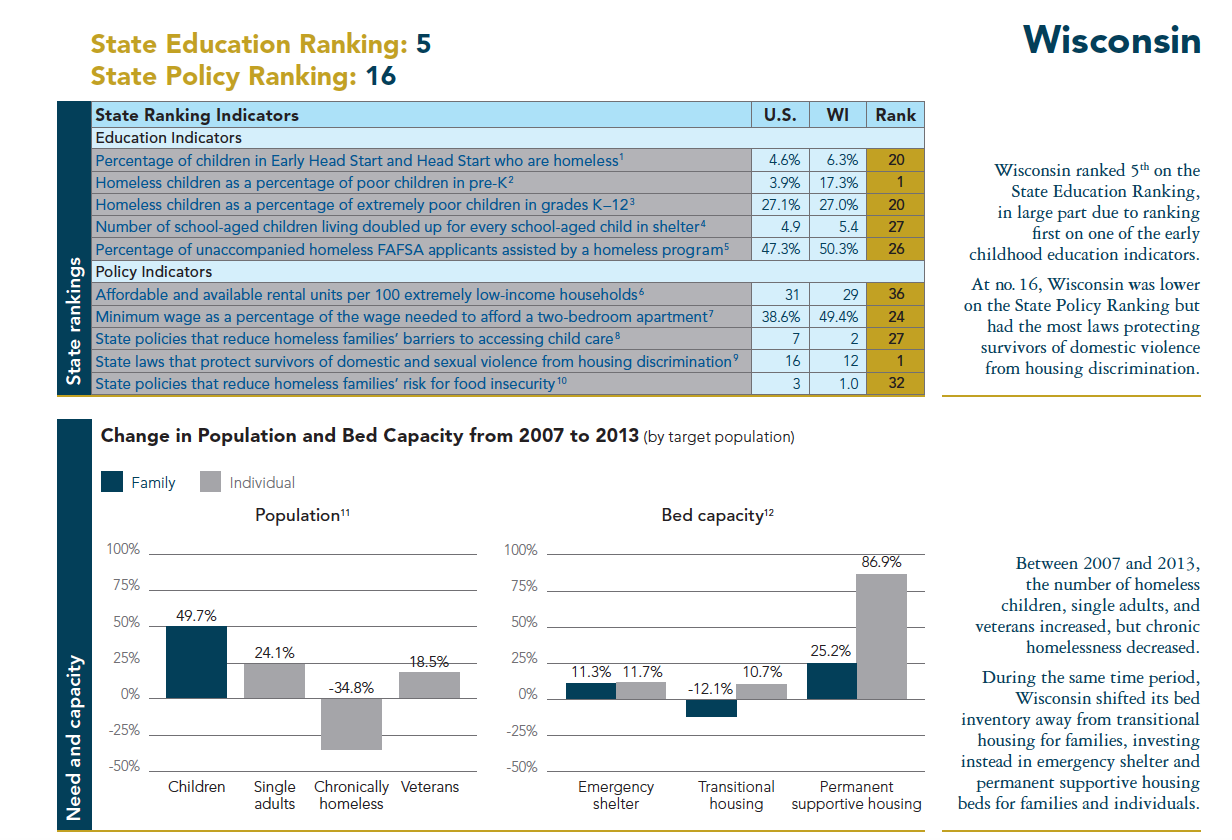

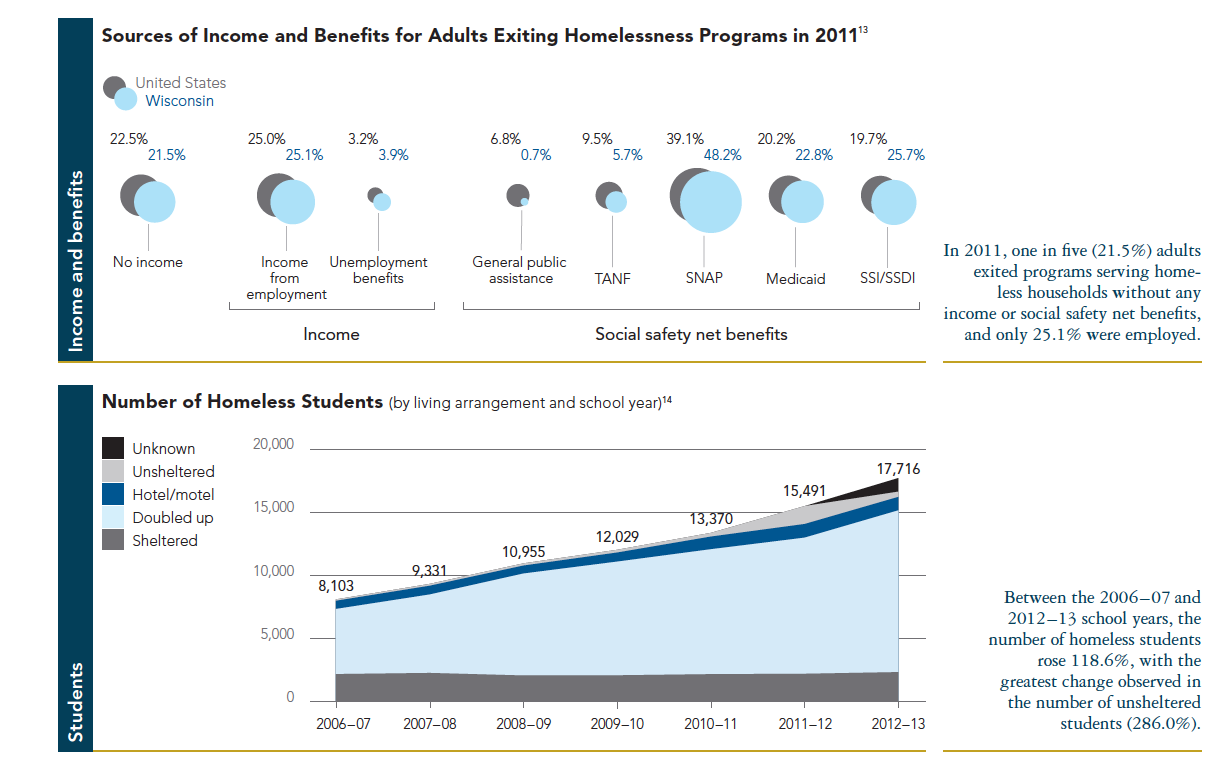

Example 2 Wisconsin’s Pre-K

During the 2012–13 school year, 1,887 homeless children between the ages of three and five were enrolled in a state pre-K program in Wisconsin. As a percentage of all poor children enrolled, homeless children made up 17.3%, the highest rate of any state. Although a greater number of poor children were enrolled in pre-K in 27 other states, only three states served more homeless children than Wisconsin. The state’s commitment to improving early childhood education has been recognized on the national level when the state was awarded a Race to the Top Early Learning Challenge (RTT-ELC) grant from the U.S. Department of Education and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in 2012. RTT-ELC is a competitive federal grant program to support states in developing high-quality early education systems, and Wisconsin is using the funding to increase consumer outreach, among other priorities.17

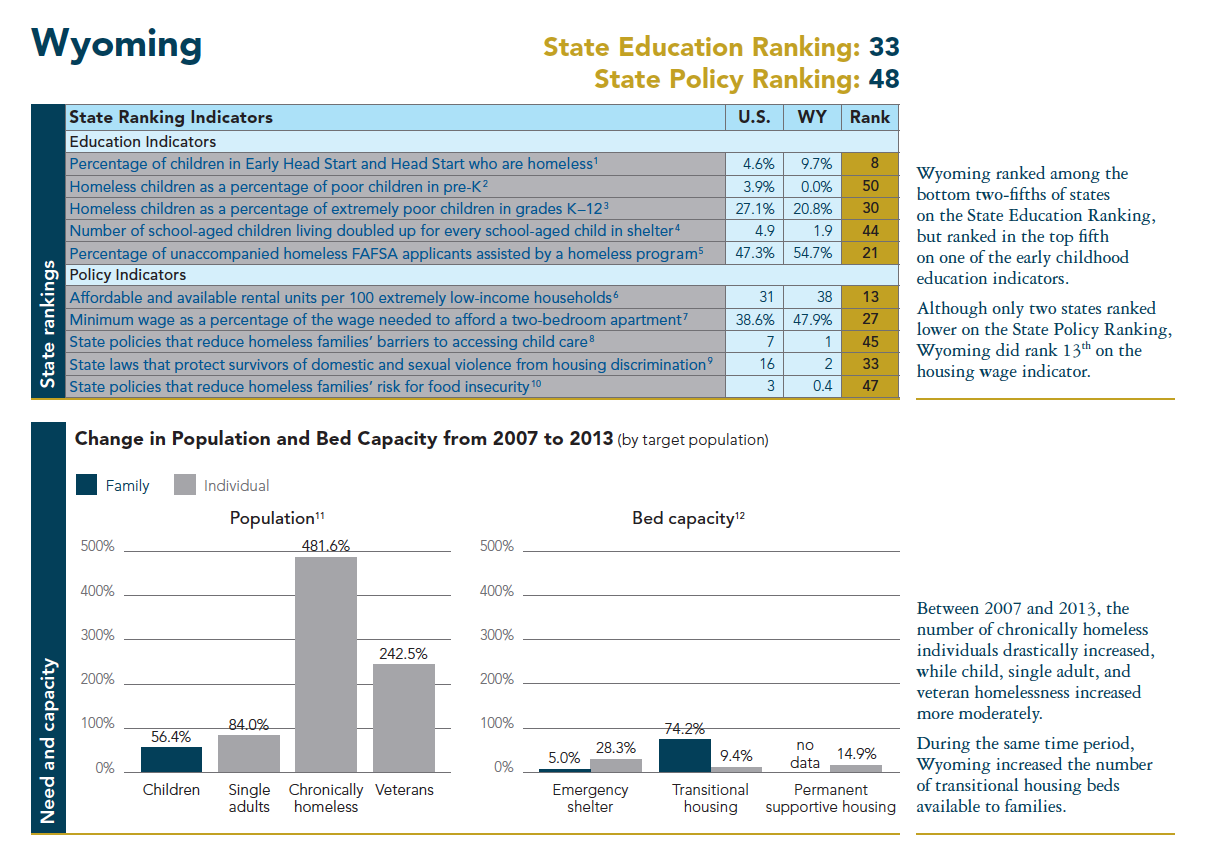

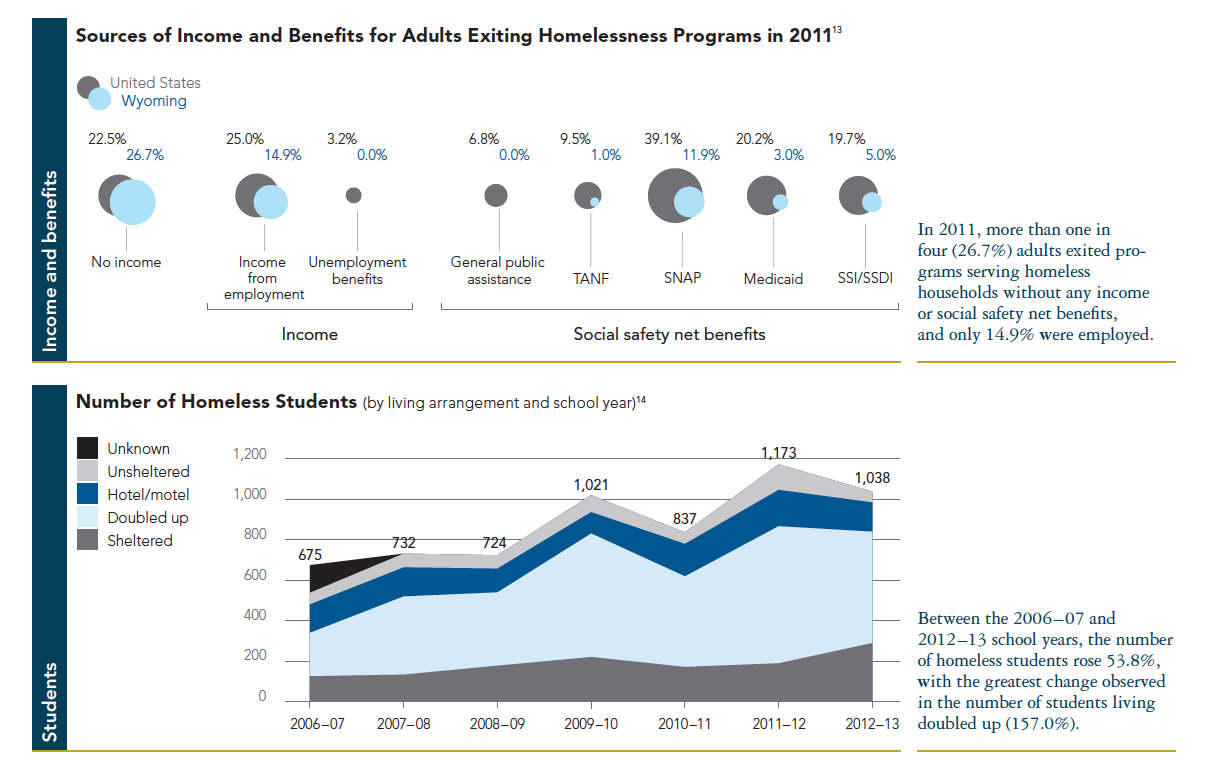

The existence of well-funded state-financed preschool programs did not necessarily guarantee greater access for young homeless children. This was the case with Vermont, Florida, and Oklahoma. These states enrolled children in state pre-K programs at the highest rates nationwide during the 2012–13 school year (46%, 40%, and 37%, respectively). While Oklahoma ranked seventh among states on the State Education Ranking’s second education indicator—homeless children as a percentage of poor children in pre-K—these results did not translate to Vermont and Florida, ranked 19th and 25th, respectively, and both states’ rates fell below the national average. States ranked 46th through 50th—Indiana, Montana, North Dakota, Mississippi, and Wyoming—all lacked state public pre-K programs. Homeless children could only enroll in local public or private pre-K in these states.18

Identifying and Serving Homeless Children in Grades Kindergarten through 12

In 2013, the U.S. Census Bureau counted 49 million children between the ages of six and 17. One-fifth (21%) of these school-aged children were poor.19 According to the U.S. Department of Education, 1.3 million students experienced homelessness during the 2012–13 school year.

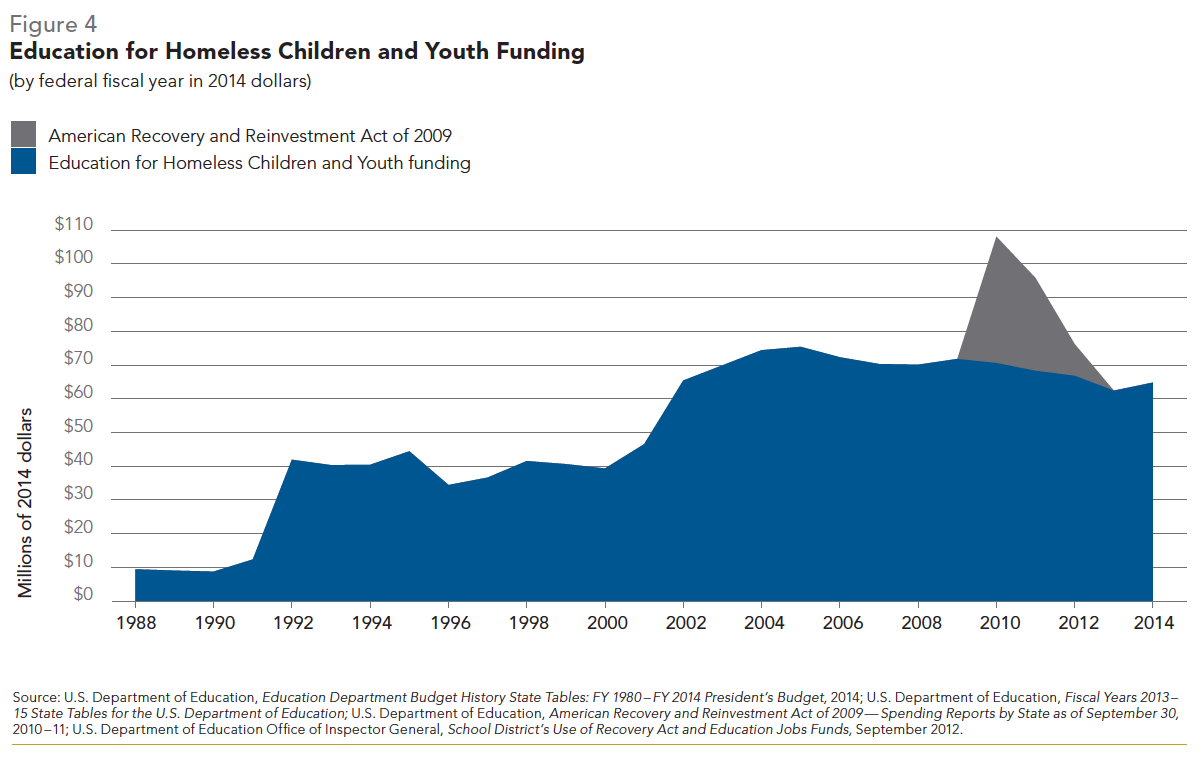

The McKinney-Vento Homeless Education Assistance Improvements Act (McKinney-Vento) guarantees homeless students the right to the same quality of education that their housed peers receive. McKinney-Vento requires that every local education agency (LEA) appoint a liaison to identify and serve homeless students, including those who are living in shelters and those in doubled-up living situations. This is an inadequately funded mandate however, as fewer than one in four of the more than 16,000 LEAs receive subgrants from the federal Education for Homeless Children and Youth program, the primary source of funding to support homeless school liaisons’ work. The few LEAs that are funded enroll roughly two-thirds of all students identified as homeless each year.

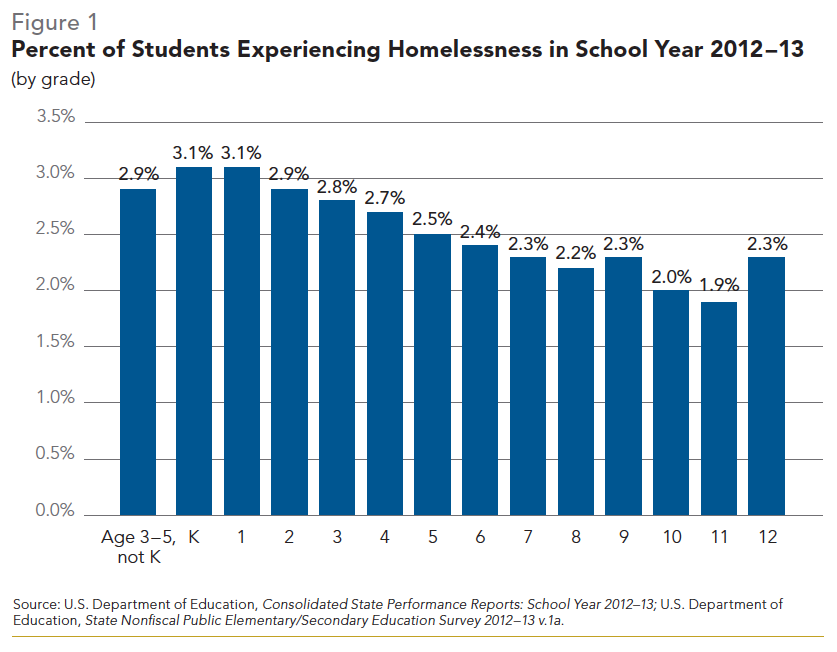

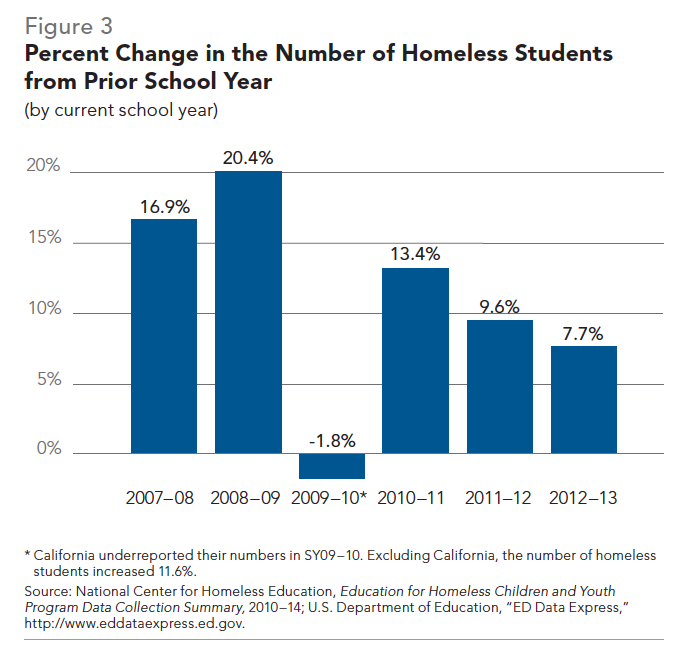

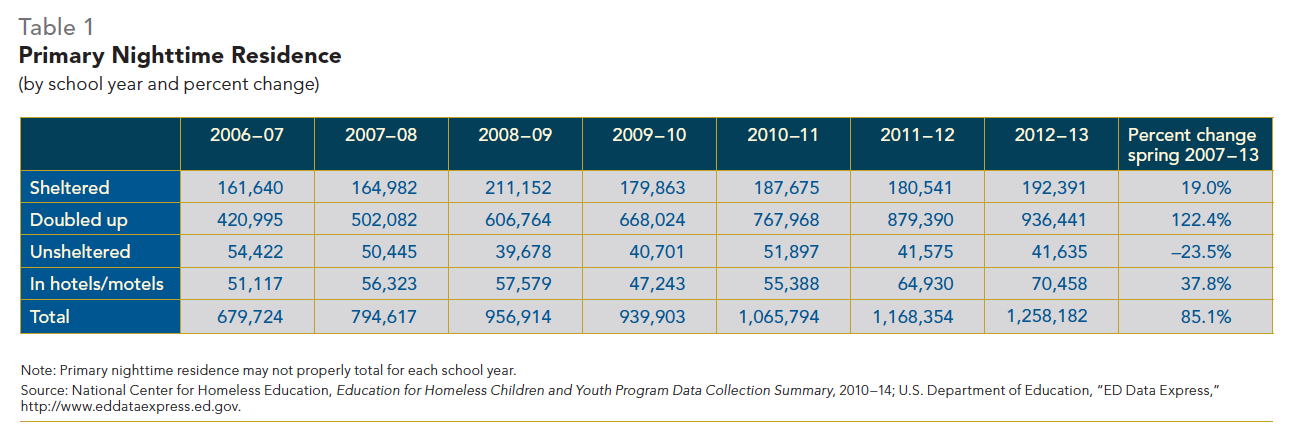

Despite limited resources, dedicated liaisons across the country have heightened outreach efforts to homeless students and have been particularly successful at identifying those in doubled-up situations, who are more difficult to account for and who often do not view themselves as homeless. The majority of the 85.1% increase in the number of homeless students between the 2006–07 and 2012–13 school years was due to a 122.4% rise in the number living doubled up.20 Identifying doubled-up students is critical given that shelter capacity is limited; 17 of 24 cities surveyed for the U.S. Conference of Mayors’ 2013 Hunger and Homelessness Survey reported turning away homeless families due to a lack of available shelter beds.21 Families sharing the housing of others due to loss of housing, economic hardship, or a similar reason may have insufficient access to basic necessities and supportive services to help them secure their own housing. Children living doubled up often move frequently as their parents exhaust their network of family, friends, and other non-relatives for places to stay. Homeless mothers may endure relationship violence to maintain these temporary living situations.22 For a detailed discussion of trends in the number of homeless students, see Issue 1: Definitions, Demographics, and Trends in Student and Family Homelessness.

The State Education Ranking uses two complementary measures to assess how well states are identifying and serving homeless students from kindergarten through grade 12: homeless children as a percentage of extremely poor children and the number of children living doubled up for every child staying in a shelter.

As with the percent of poor children in pre-K who are homeless (the second education indicator), the State Education Ranking compares the number of school-aged homeless children with those who are extremely poor (living at or below 50% of the FPL, which amounted to $9,765 for a family of three in 2013), in order to control for the effects of poverty across states. While not all families experiencing homelessness are extremely poor, the overwhelming majority of homeless families are.24 Therefore, states with higher rates of school-aged homeless children in comparison with those of extremely poor children are likely more effective at identifying and enrolling homeless students.

The national rate of homeless children as a percentage of extremely poor children was one-quarter (27.1%) during the 2012–13 school year. In other words, one out of every four school-aged children who lived in extreme poverty experienced homelessness. Led by Alaska (69.4%), Utah (48.0%), California (45.4%), and New York (45.4%), 19 states surpassed the national average on this third education indicator (Example 3). Rhode Island (8.1%), New Jersey (8.7%), and Connecticut (8.9%) had the lowest ratios of school-aged homeless to extremely poor children, indicating that these states are less successful in conducting outreach to and identifying homeless students.25

Example 3 Alaska’s Homeless Students

At 69.4%, Alaska had the highest ratio of school-aged homeless to extremely poor children of any state during the 2012–13 school year. More than two out of three school-aged children who lived in extreme poverty were identified as homeless.

In the 2012–13 school year, 59% of homeless students were identified as living doubled up, 23% in shelter, 8% in hotels or motels, and 10% unsheltered. Since the rate of doubled-up students is near the national average, Alaska has been successful in identifying students living in doubled-up situations, despite only five of the 54 LEAs in Alaska receiving funding through McKinney-Vento subgrants. For LEAs with and without subgrants, the difference in identified homeless students is stark: 3,882 versus 161, respectively. This may be a reflection of the population concentration in Alaska, where the vast majority of people reside in a few areas of the state.23

Since the percentage of students living doubled up (75.5%) is about five times higher than that of those living in shelter (15.5%) nationwide, states with high numbers of sheltered students compared with doubled-up students are likely not as effective at identifying homeless students in doubled-up situations. The national number of school-aged children living doubled up for every school-aged child staying in a shelter— the fourth education indicator—was 4.9 in school year 2012–13. In other words, for every school-aged child living in a shelter, there were nearly five (4.9) school-aged children staying doubled up with another household due to loss of housing, economic hardship, or a similar reason. Twenty-eight states were above the national average, led by Mississippi (22.2), Utah (15.9), and Louisiana (13.0) (Example 4). Massachusetts (1.4), Hawaii (1.5), and New York (1.5) identified the fewest students living doubled up compared with those in shelter.28

Example 4 Mississippi’s Doubled-up Students

Mississippi identified the most children living doubled up (11,655) compared to children staying in shelter (524) of any state during the 2012–13 school year. For every school-aged child living in shelter, Mississippi identified 22 school-aged children living doubled up.

One explanation for Mississippi’s high sheltered-to-doubled-up ratio could be that homeless school liaisons are working diligently to identify vulnerable students despite receiving limited federal assistance to carry out this mission. Only 18 of Mississippi’s 151 LEAs received McKinney-Vento subgrants in School Year 2012–13.26 Another possible explanation is that the limited availability of family shelters in the state forces many homeless families to stay with friends and family members.27

Encouraging Unaccompanied Homeless Youth to Attend College

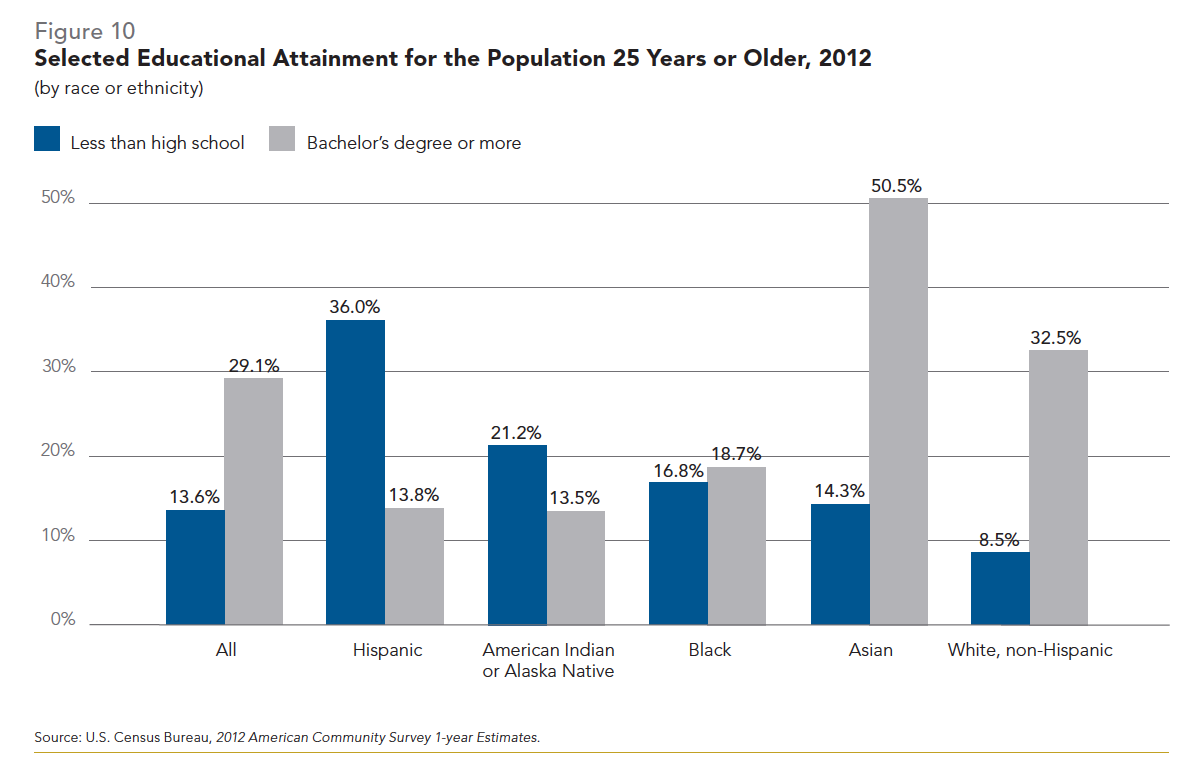

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, there were 21 million students enrolled in college, graduate, and professional schools in 2013, and almost one-quarter (24%) of these students were living in poverty. Completing higher education benefits students’ future employment and earnings. In 2013, college graduates were three times less likely to be poor and two times less likely to be unemployed than adults with only high school diplomas. Over the course of 40 years, adults with bachelor’s degrees earn nearly twice as much as workers with high school diplomas.29 What is not known, however, is the number of college students who are homeless. The State Education Ranking uses the number of homeless students unaccompanied by a parent or guardian who file the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), which is the only available data on college students experiencing homelessness.

The college admissions process can be overwhelming for any young adult. For youth experiencing homelessness, the fees associated with applying to college—Advanced Placement exams, entrance exams such as the SAT, and college applications—can be barriers to applying. An additional challenge for homeless students is filing the FAFSA, typically completed in late winter or early spring of the year in which students plan to enter college. In order to be evaluated for federal student aid, students or their parents must complete the FAFSA, which requires parents’ financial information. Students experiencing homelessness, and unaccompanied homeless youth in particular, may not be able to provide this information and may be denied aid for submitting an incomplete application. Unaccompanied homeless youth can have this requirement waived and apply for aid as an independent student if a school liaison, shelter staff, or a runaway and homeless youth program administrator can verify that they are homeless.

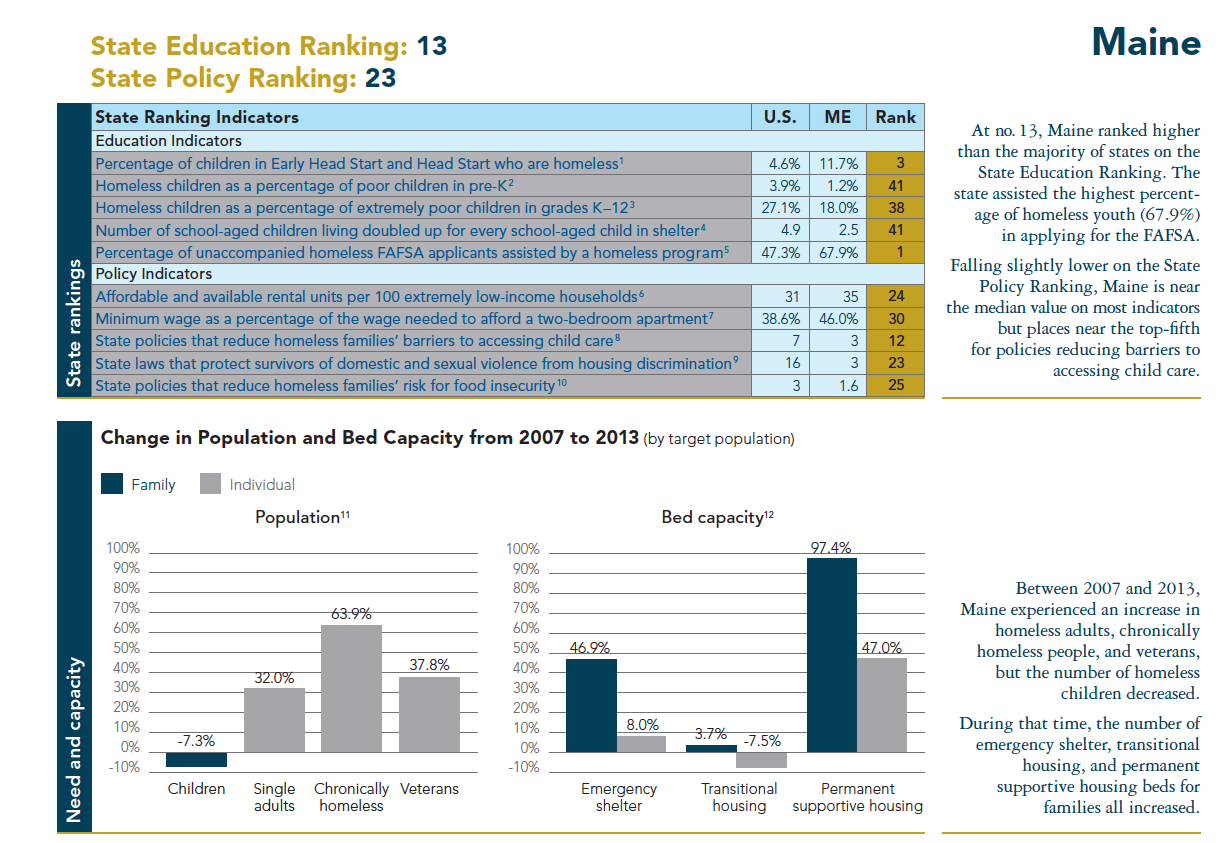

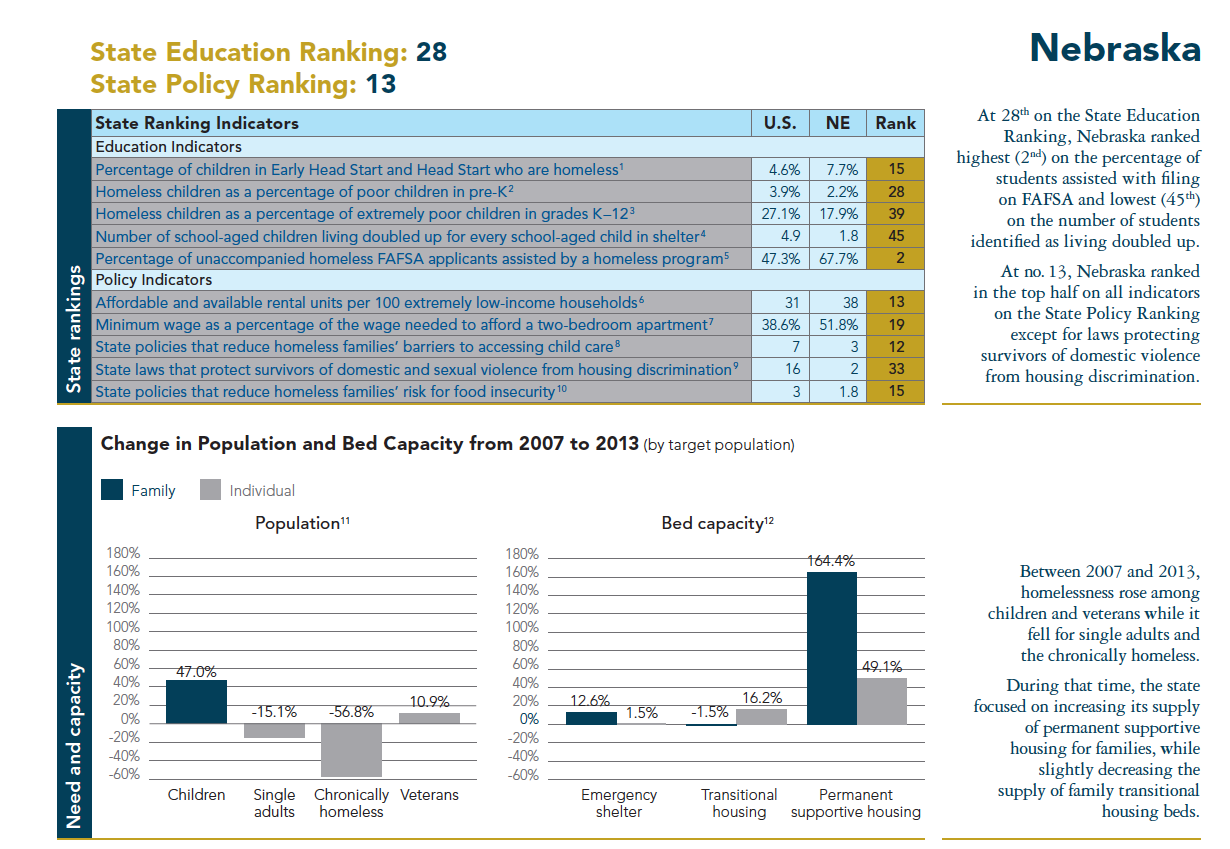

Not all unaccompanied homeless students applying for financial aid are assisted by a school, shelter, or youth program. Less than half (47.3%) of college-bound unaccompanied homeless students nationwide received help filing the FAFSA during the 2012–13 application cycle. On this last education indicator, 33 states had rates higher than the national average, with school, shelter, and youth program representatives in Maine (67.9%), Nebraska (67.7%), South Dakota (67.6%), and Alaska (66.0%) aiding the highest percentage of applicants (Example 5). The lowest rates were found in California (32.3%), Hawaii (33.6%), and Florida (38.3%).31

Example 5 Maine’s Help on Filing the FAFSA

Of the 299 unaccompanied homeless students in Maine who completed the FAFSA during the 2012–13 application cycle, 203, or 67.9%—the highest percentage in the nation—were assisted by a school liaison, shelter staff, or runaway and homeless youth program administrator. The number of FAFSA filings in Maine is low overall; only 17 states had fewer applications from homeless students and 13 states had fewer total students completing the FAFSA. Predominantly rural states with fewer students completing the FAFSA generally had the highest rates of unaccompanied homeless FAFSA applicants assisted by a school, shelter, or youth program—after Maine, the highest rates were found in Nebraska, South Dakota, and Alaska.30

State Policy Ranking

Enacting Policies to Support Homeless Families and Prevent Homelessness

While families often become homeless for a variety of reasons, lack of available affordable housing is an important factor, particularly in areas with relatively low wages. Survivors of domestic violence can become homeless due to a lack of policies to protect tenants’ housing rights. Once housing is lost, it can be challenging for parents to meet their family’s basic needs, which further hinders attempts to gain stability. Parents experiencing homelessness have an especially urgent need for child care as they struggle to find housing, employment, and other services. Parents also face the added stress of trying to adequately feed their family. Many policy decisions made at the state level determine what resources and services families can access and what protections they have.

Taking all of these factors into account, the ICPH State Policy Ranking looks at specific policies that states should enact to better serve homeless children and their parents. The ranking examines not only the availability and affordability of housing, but also states’ efforts to improve homeless families’ access to child care, protect survivors of domestic violence from housing discrimination, and reduce homeless families’ risk for food insecurity. For the latter three indicators, states ranked higher when they had more of the laws or policies described. Each of these components is not only under the control or influence of the state, but each can also have a significant impact on the lives and experiences of homeless families. Changes in the areas assessed are actionable, feasible, and vital to reduce the negative impacts of homelessness on children and families.

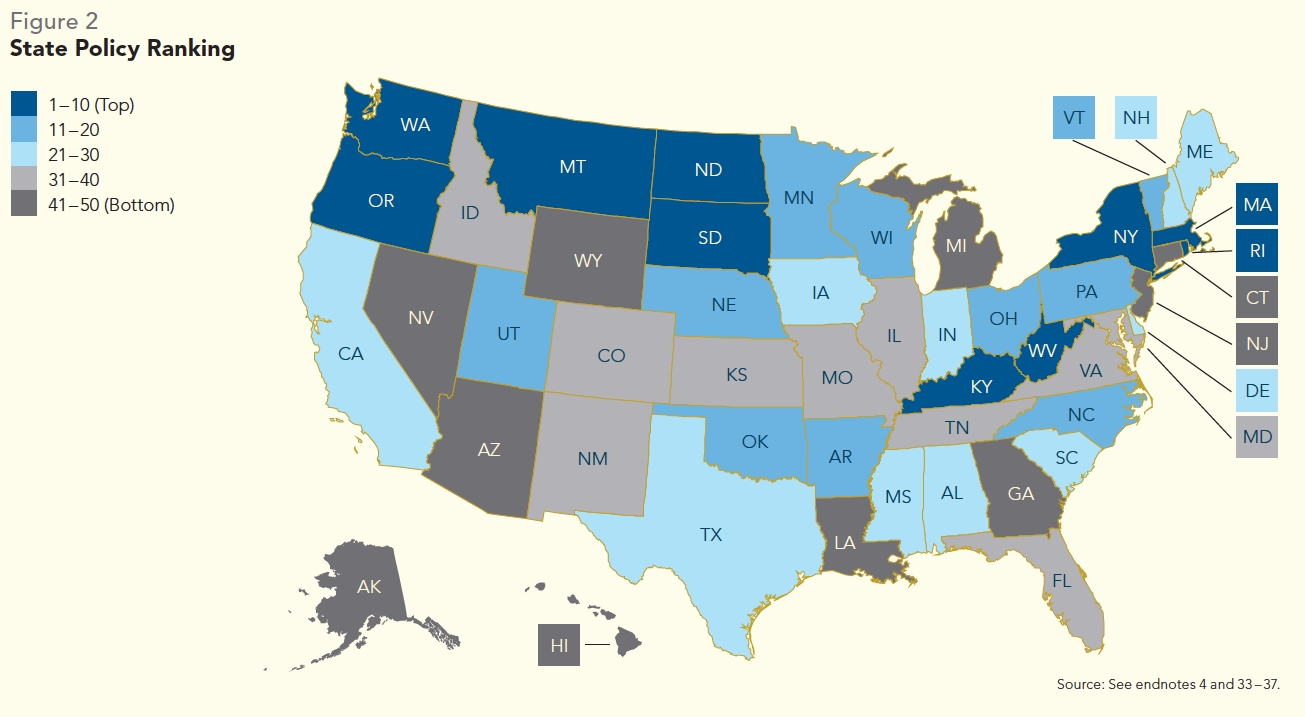

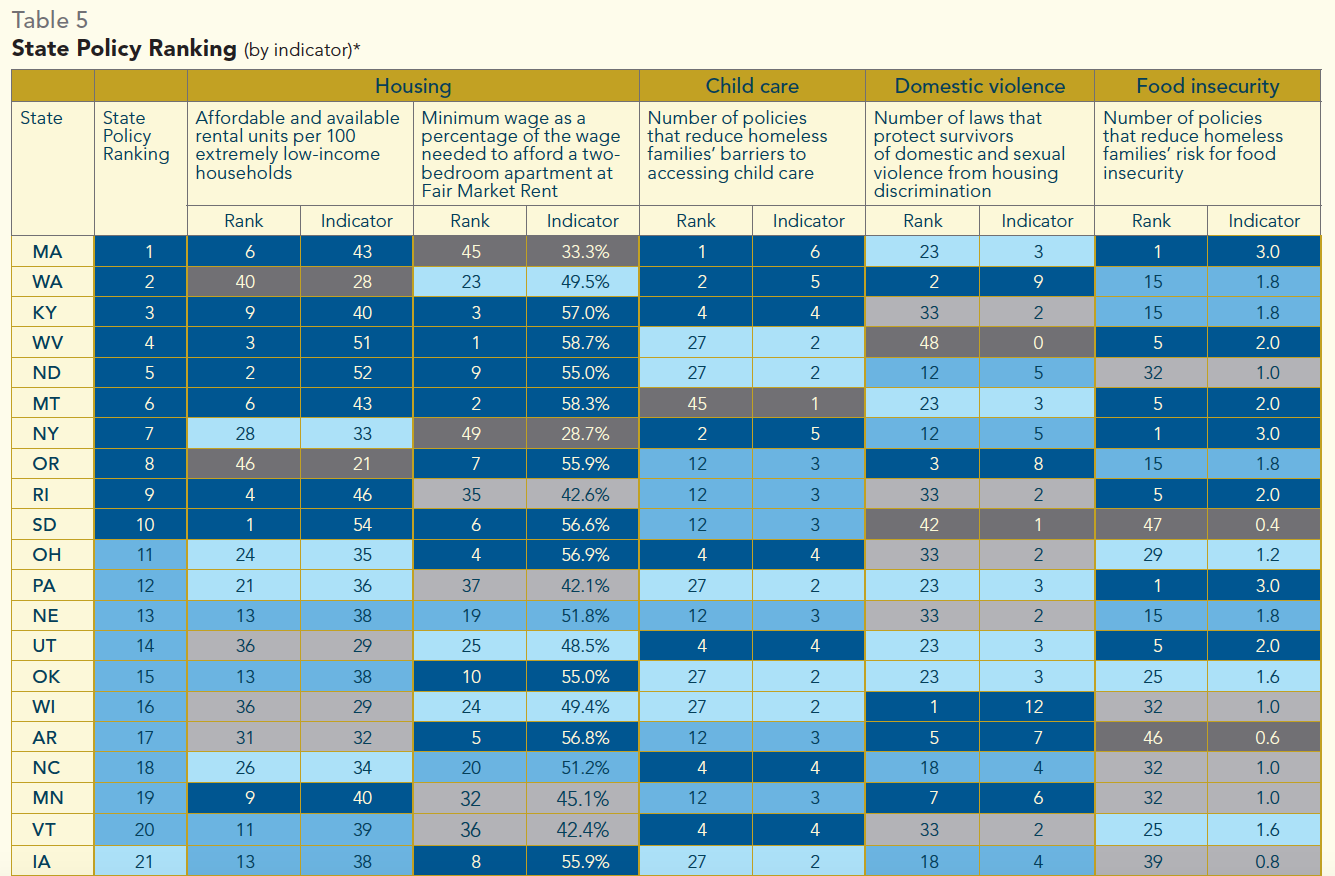

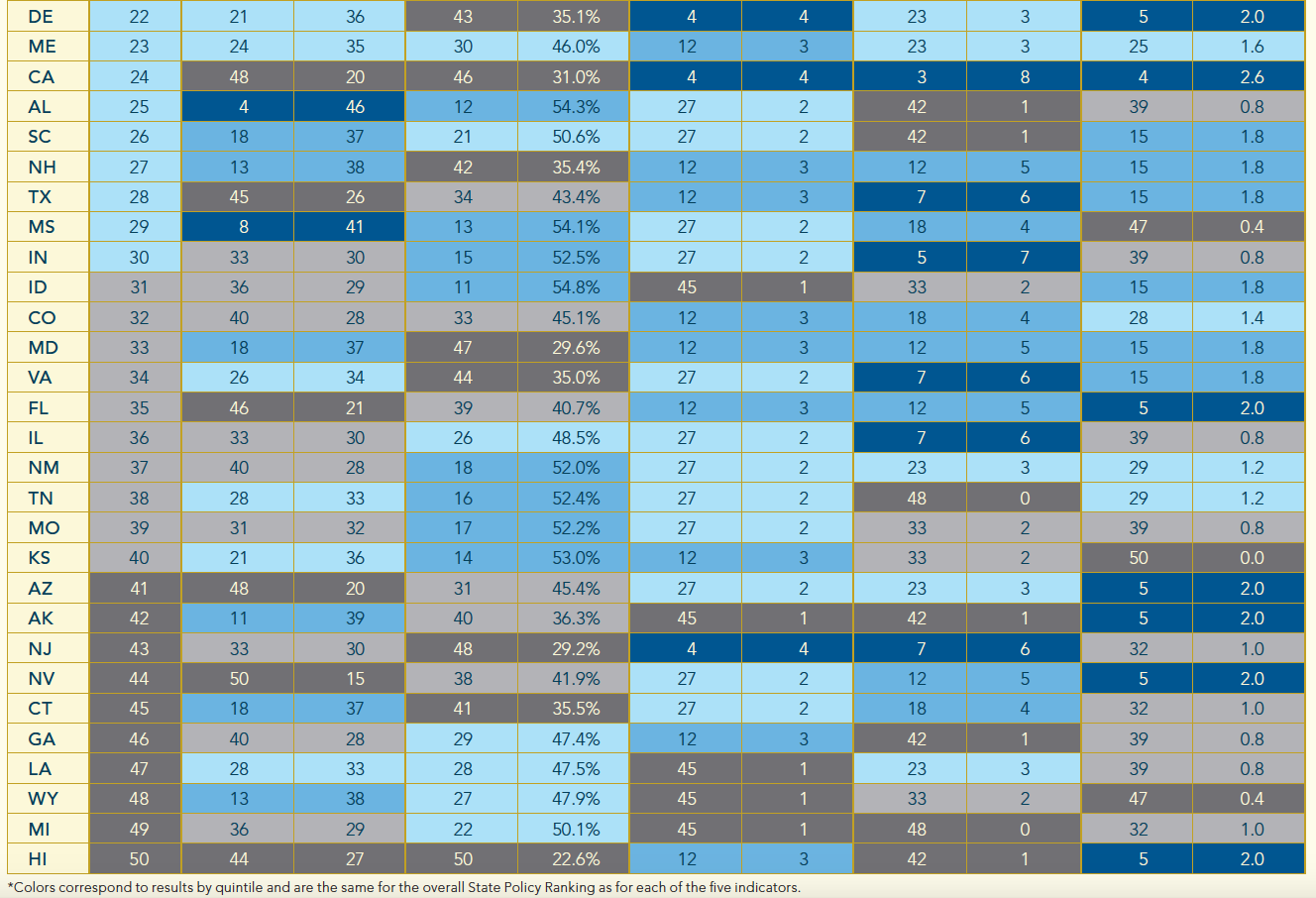

The State Policy Ranking measures are shown in Table 4. The states with the most proactive policy context for supporting homeless families are in the western and mid-Atlantic regions, with the notable exception of top-ranked Massachusetts in New England (Figure 2), with Wyoming, Michigan, and Hawaii sitting at the bottom of the ranking (Table 5).32

Housing Affordability for Extremely Low-income Families

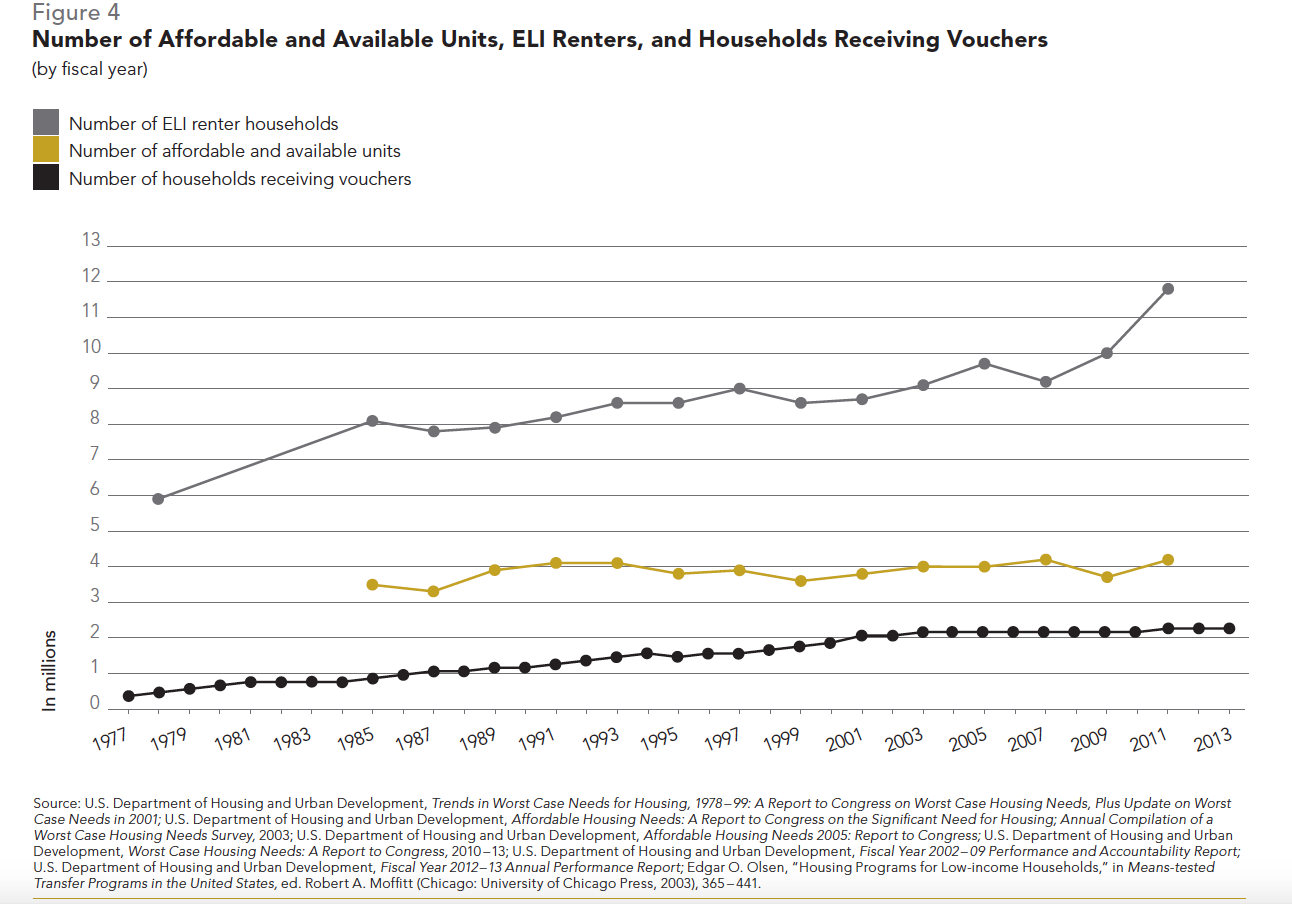

Lack of affordable housing is one of the main drivers of family homelessness. For housing to be considered affordable, a family must spend no more than 30% of its income on housing costs. More than half (51.5%) of all households in the United States were rent burdened in 2013 and more than one-quarter (26.5%) were severely rent burdened, spending over 50% of their income on rent. Three-quarters (75%) of extremely low-income (ELI) renter families—those earning 30% or less of their local area’s median income—were severely rent burdened. These families are only a small financial crisis away from losing their housing.40

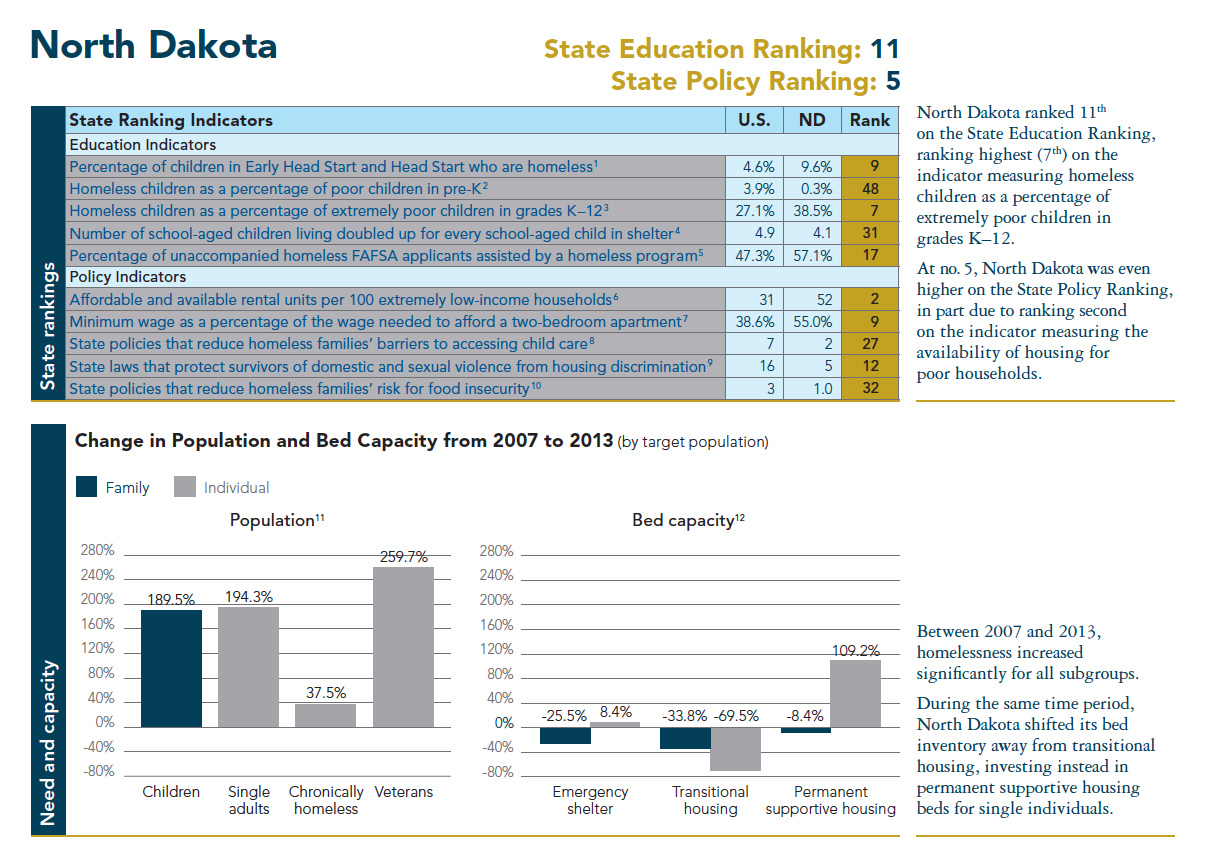

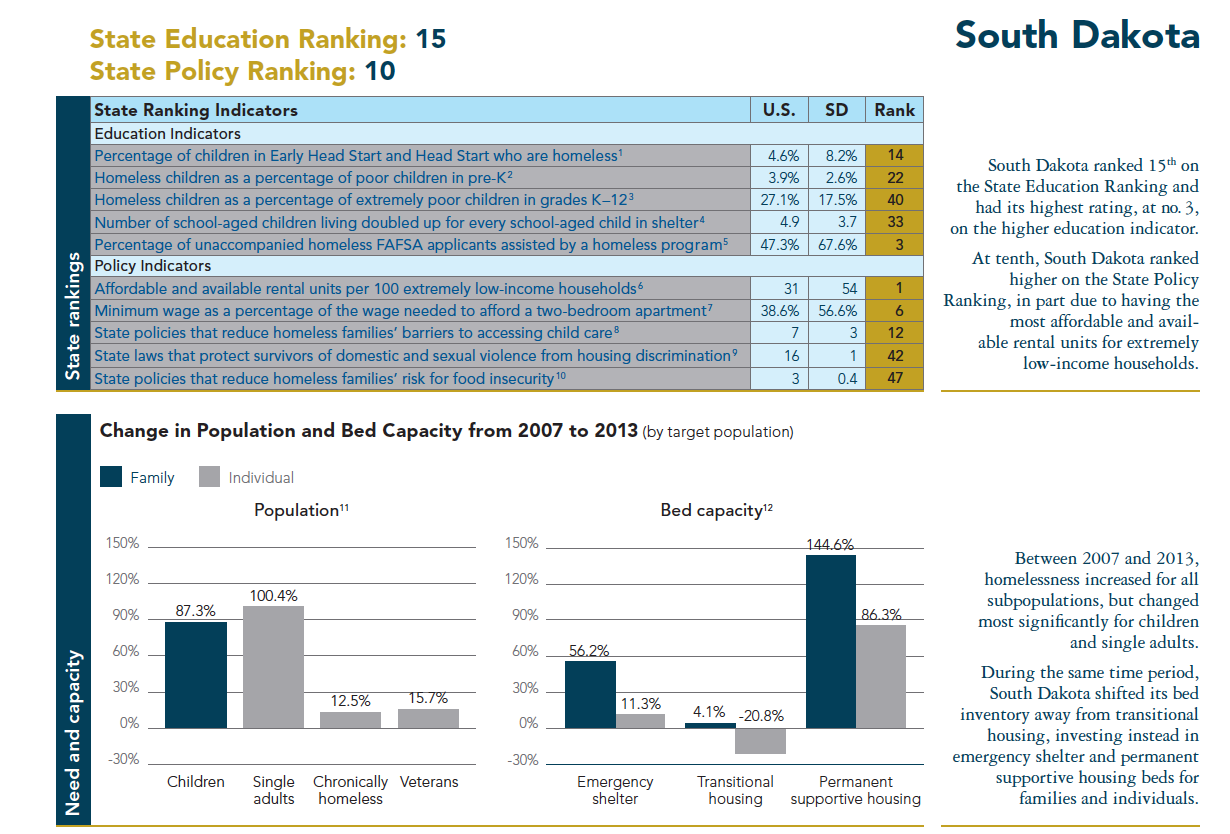

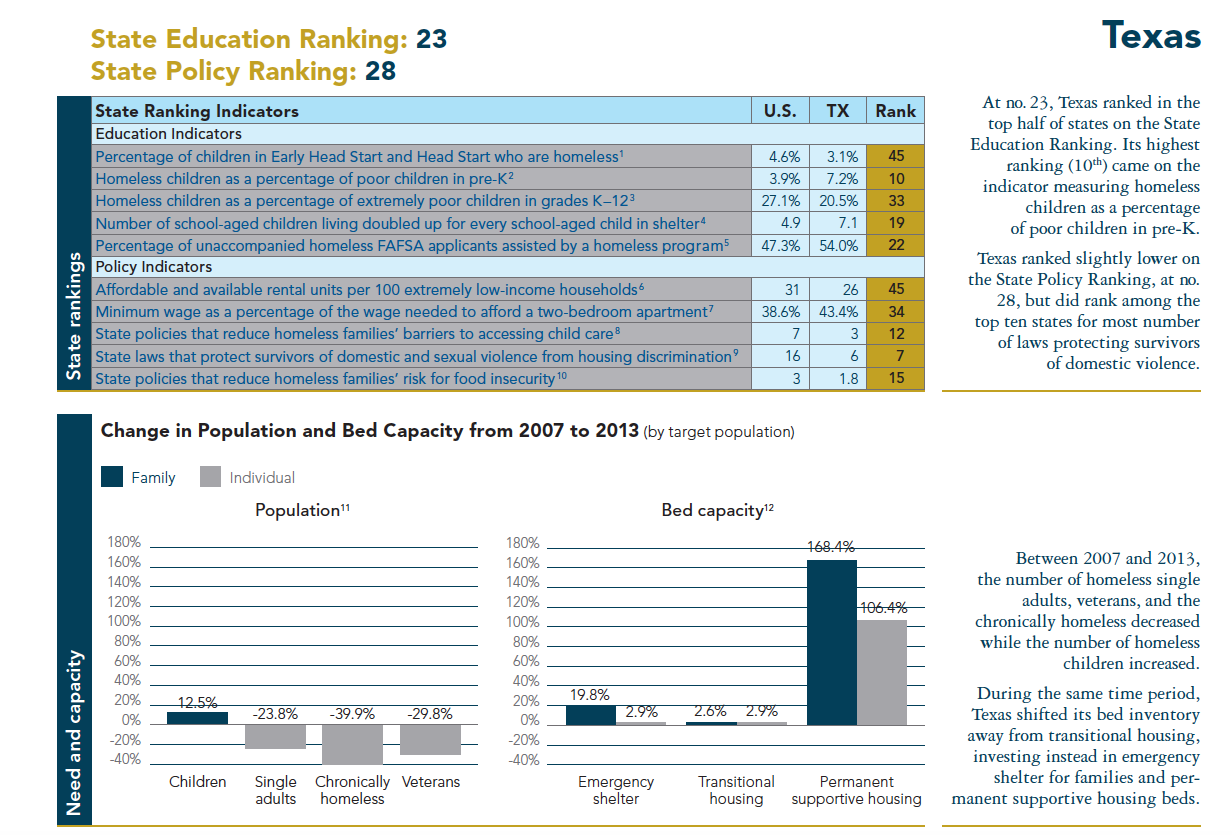

In 2012, the demand for affordable housing among ELI families far exceeded the supply in every state. The average number of affordable and available units per 100 ELI households was 31 in 2012. In other words, only 31% of ELI households could access affordable housing.41 Led by South Dakota (54 [Example 6]) and North Dakota (52), 32 states surpassed the national average on this first policy indicator. ELI households in Nevada (15), Arizona (20), and California (20) had the most difficulty finding affordable housing. For a detailed discussion on the shortage of affordable housing, see Issue 2: Macroeconomic Causes of Family Homelessness.

Example 6 South Dakota’s Affordable Housing

Fifty-four out of every 100 ELI renters in South Dakota could theoretically find an affordable and available rental unit. While this places the state at the very top on the affordable housing indicator, many of its low-income residents still struggle to find affordable rental housing. The state’s more favorable rental market is mostly explained by its low housing costs. Large variations exist within the state, with the most severe deficits in affordable housing availability (less than 25 units per 100) seen in the more populous counties in the southeast and southwest.38 The same clusters of counties also experience the highest rates of homelessness.

South Dakota enjoys a low unemployment rate (3.8% in 2013 compared with 7.4% nationwide), masking the fact that despite working full-time, the average renter cannot afford a FMR apartment. At $9.70 per hour, the average wage for a South Dakota renter falls short of the housing wage ($12.82). At $7.25, the minimum wage is even more insufficient, however, South Dakota did vote in 2014 to increase the minimum wage from $7.25 to $8.50 beginning in 2015. Of the state’s 22% ELI renters in 2014, 78% are cost burdened and 57% are severely cost burdened.39

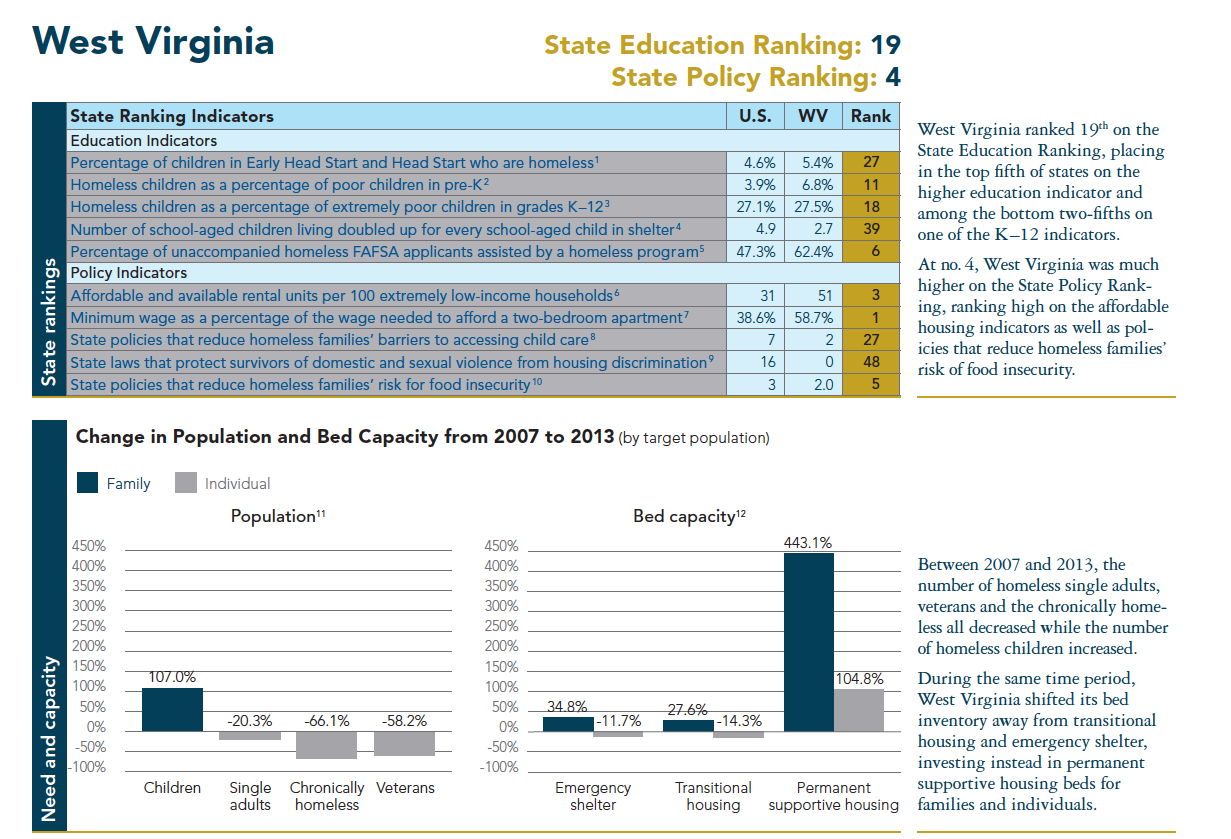

With low levels of education and limited work experience, the majority of homeless families only qualify for minimum-wage jobs. Due to a severe lack of affordable housing, even those who work full-time and earn the minimum wage struggle to find and maintain housing. Measuring the minimum wage against the “housing wage”—the wage needed to afford a two-bedroom apartment at Fair Market Rent (FMR)—reflects how likely families are to be able to afford housing in a specific state, thereby lowering the risk of homelessness. On this second policy indicator, the average minimum wage amounted only to two-fifths (38.6%) of the housing wage needed to afford a two-bedroom apartment in 2013. In no state could a family with a single wage-earner working full-time at the minimum wage afford a two-bedroom FMR apartment. The minimum wage covered the greatest proportion of the housing wage in West Virginia, at 58.7% (Example 7), and the lowest, 22.6%, in Hawaii. Heads of households in every state, then, could be working full-time and find themselves homeless. The gap between the minimum wage and the housing wage underscores both the dearth of affordable housing and the limited purchasing power of the minimum wage. Even if the minimum wage was raised to $10.10 per hour in every state, the amount specified in the Minimum Wage Fairness Act of 2014, families earning the minimum wage for full-time work would still not be able to afford a two-bedroom apartment in any state.43

Example 7 West Virginia’s Minimum/Housing Wage

The minimum wage goes the furthest in covering the housing wage in West Virginia. The FMR for a two-bedroom apartment in West Virginia is $642 per month. For this rent to be considered affordable, a household would have to earn $2,141 per month or $25,693 per year. To calculate the housing wage, that annual income is broken down into an hourly rate. Based on a 40-hour work week with 52 weeks in a year, the housing wage is $12.35. The federal hourly minimum wage of $7.25, the same as the West Virginia state minimum, accounts for 58.7% of the state’s housing wage. While this is the highest percentage of any state, it still falls far short of the income needed to afford a two-bedroom apartment at FMR. A full-time minimum wage earner would have to earn $5.10 more per hour or $10,613 more per year to afford that apartment.

In 2013, 31 states in addition to West Virginia had a minimum wage of $7.25. West Virginia ranks highest on this policy indicator, then, because the cost of a two-bedroom apartment at FMR in West Virginia is the lowest of all those states. In 2014, West Virginia moved to increase the minimum wage to $8.00 in 2015 and $8.75 in 2016, which will likely help more families avoid the consequences of rent burden.42

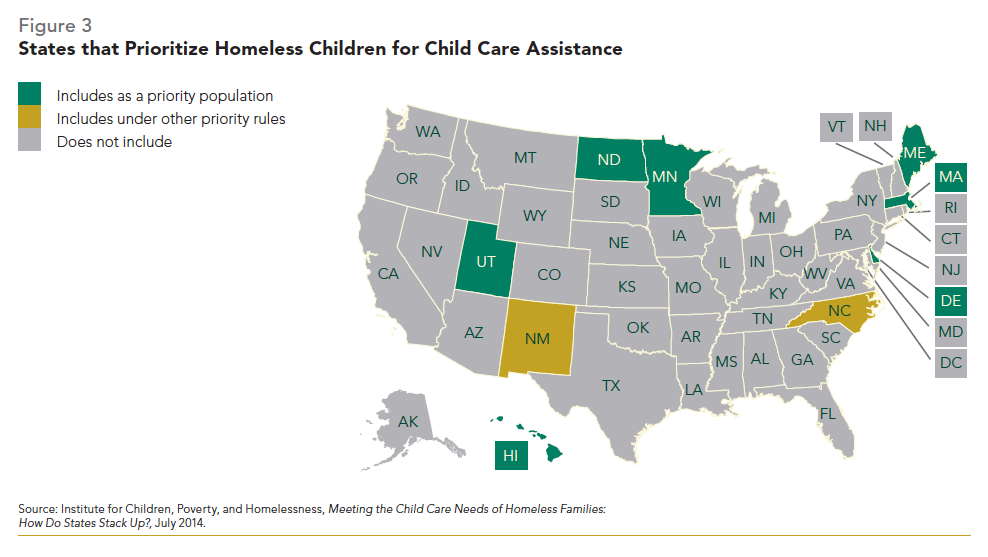

Policies Reducing Homeless Families’ Barriers to Child Care

Child care is critical for homeless families, especially those headed by a single parent, to find and maintain employment. However, homeless families face several barriers to accessing child care. In addition to the high cost of child care— in 2012, the average annual cost of center-based child care for a four-year-old was $7,817, nearly half the income for a family of three living in poverty—finding a child care provider who can accommodate homeless families’ often irregular and unpredictable schedules can be challenging. Although child care subsidies are intended to provide low-income families with affordable and flexible child care options, some homeless families are deterred by restrictive documentation and eligibility requirements.46

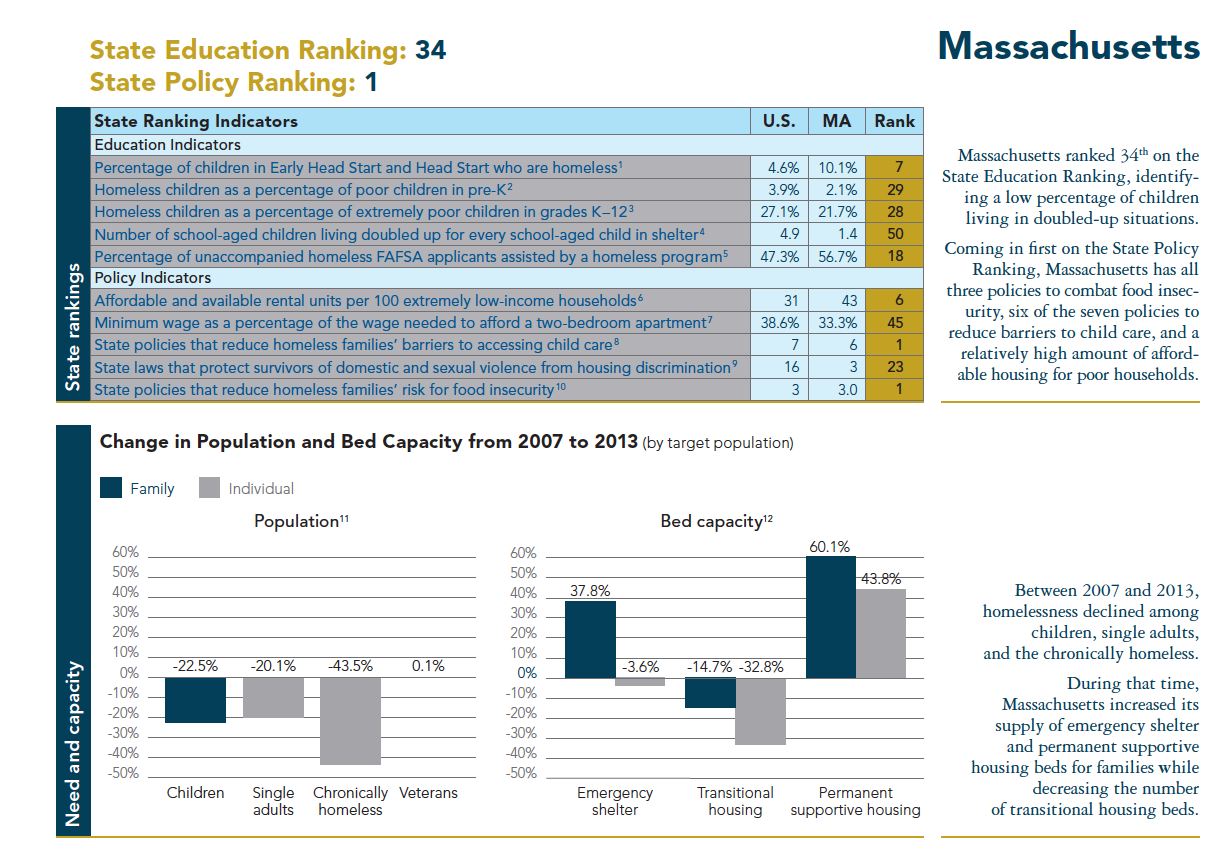

In administering the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), the primary federal source of child care assistance for low-income families, states have the flexibility to develop many of their own eligibility rules. States can improve homeless children’s access to subsidized child care by: including homelessness as a reason for needing care (making it its own eligibility category), including homeless children as a priority population to serve, providing care while parents look for a job or housing, waiving co-payments, establishing higher reimbursement rates for providers offering care during nontraditional hours, extending initial child care eligibility to 12 months, and extending eligibility while children participate in Head Start. According to states’ CCDF plans for federal Fiscal Years 2014–15, no state has instituted all seven of these policies, but every state has at least one. Massachusetts (Example 8) performed the best on this third policy indicator with six in place, while five states are tied for having the fewest, with only one of the seven policies: Alaska, Idaho, Louisiana, Michigan, and Montana.47 For a detailed discussion on child care, see Issue 2: Macroeconomic Causes of Family Homelessness.

Example 8 Massachusetts’ Child Care Policies

With six of the seven child care subsidy policies analyzed, Massachusetts ranks highest among all states. In Massachusetts, subsidies may be used during time spent searching for a job or housing, and parents are initially deemed eligible for care for a period of 12 months. In addition, homeless children may be eligible for subsidized care due to a need for protective services, which would enable them to receive care without the family meeting the traditional work and training requirements. The copayment and income eligibility requirements may be waived in these protective services cases. Massachusetts also prioritizes homeless families among low-income families and will waive copayments for those with incomes at or below the FPL. Lastly, child care providers serving priority populations receive additional funding for services such as case management and transportation.

Massachusetts has dedicated substantial fiscal and personnel resources to child care quality and access, becoming, in 2005, the first state with a separate agency overseeing the provision and oversight of early childhood education and care services. The Massachusetts Department of Early Education and Care (EEC) manages the state’s child care program and collaborates with other government agencies in the state, including the Department of Housing and Community Development, in setting and implementing their CCDF policies. In addition to the policies described above and compared to other state agencies, EEC has made a special effort to address the care needs of homeless families and collaborate with homelessness service providers. EEC allows up to six months for certain priority populations, including homeless families, to provide medical records necessary for enrollment.44 With a portion of the quality improvement funding the state is awarded for administering CCDF, EEC supports outreach to hard-to-reach populations and walk-in services for homeless families. Massachusetts is one of only 13 states that serves at least some subsidy recipients through contracts or subgrants—in FY12, Massachusetts served 40% through this method—and sets aside grants for “homeless child care.” EEC contracts with programs that provide child care to homeless children; one of the aims is to ensure that the parents of these children have access to other supportive services they may need to secure housing and work.45

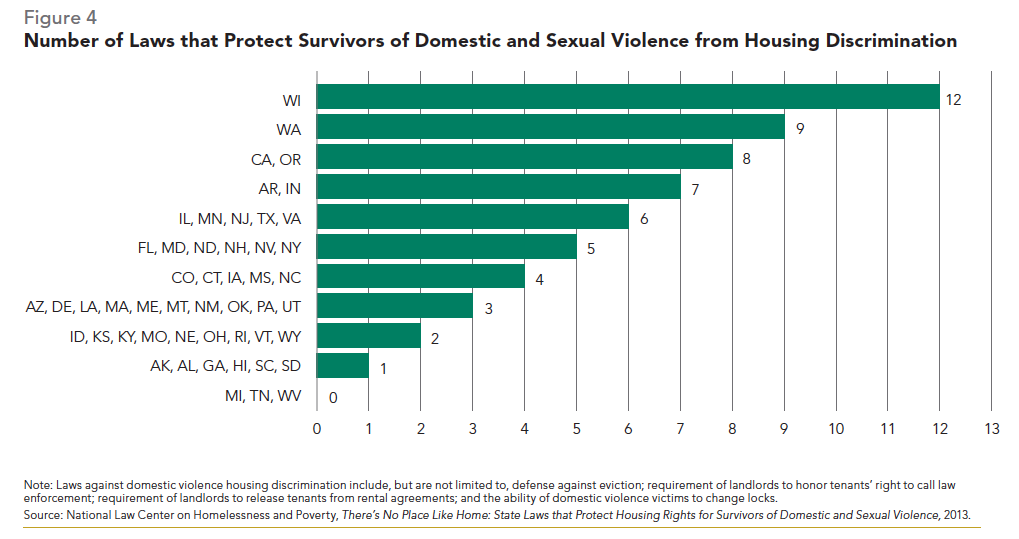

Laws Protecting Survivors of Domestic Violence from Housing Discrimination

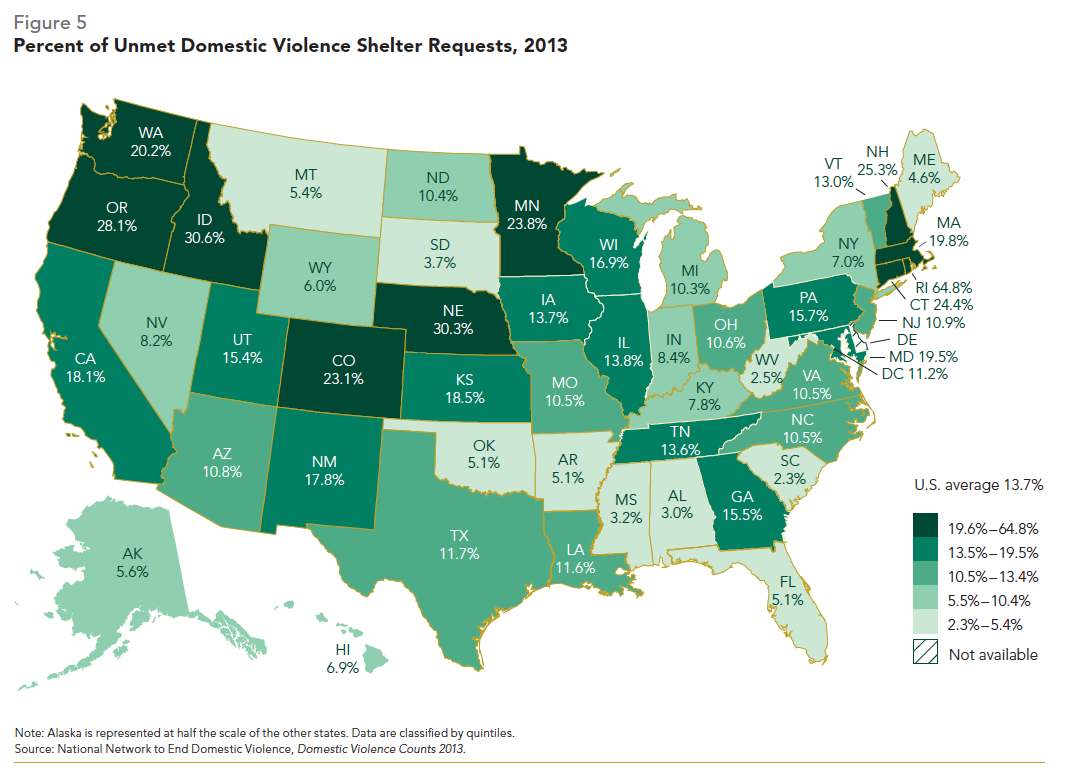

One out of every four homeless women is homeless as a direct result of domestic violence, and over 90% of homeless mothers experience severe physical and/or sexual abuse during their lifetimes.48 Individuals who escape their abusers often have limited financial resources and face discrimination in the housing market, leaving them with few safe housing options. Although the 2013 reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act extended federal housing protections to survivors of domestic violence in all federally subsidized housing programs, those living in other housing situations may still be at risk of eviction or losing their housing.

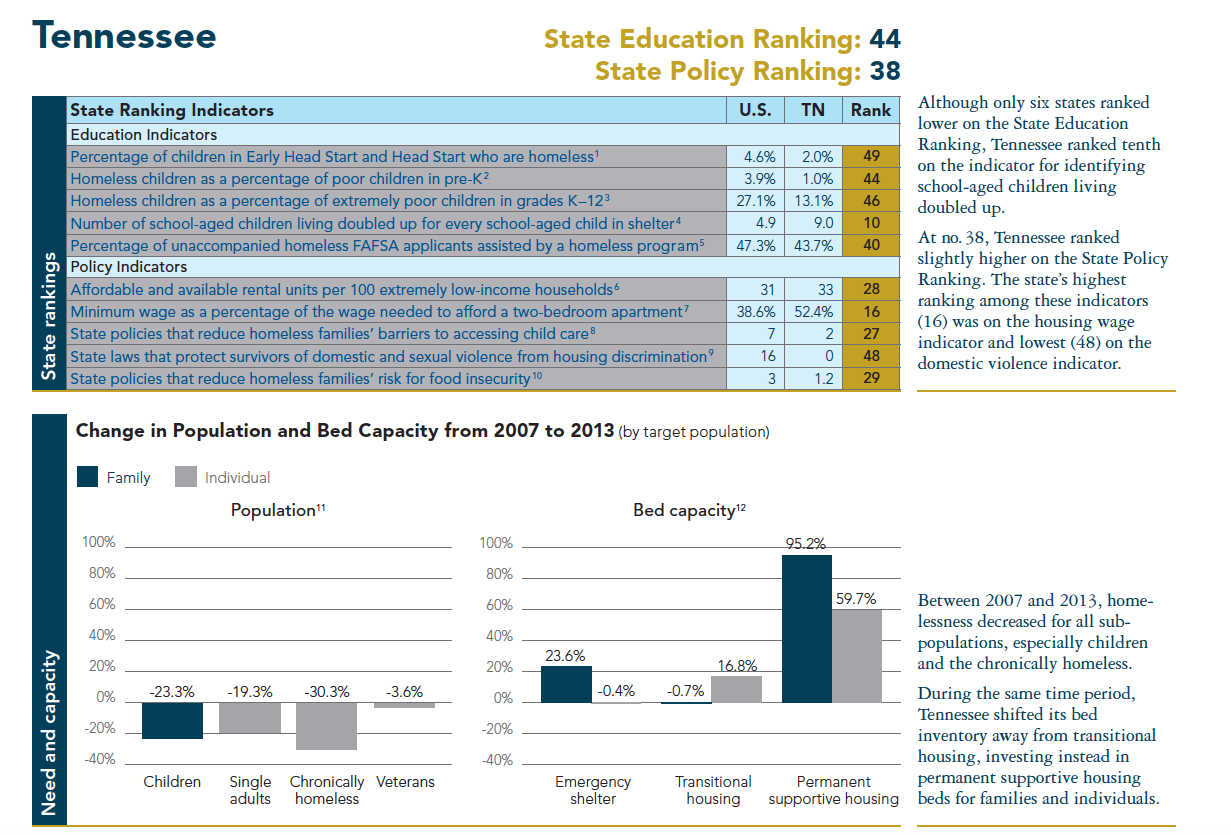

A number of states have adopted legislation providing additional protections and rights to survivors of domestic violence, such as prohibiting tenants from waiving their right to call police, enabling survivors to terminate leases early without penalty, and providing relocation or housing assistance. For this fourth policy indicator, 16 state laws were used that had been reviewed in the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty’s report, There’s No Place Like Home: State Laws that Protect Housing Rights for Survivors of Domestic and Sexual Violence. Wisconsin had the most laws, with 12 (Example 9). Washington, the state with the second-highest number of laws, had nine. Three states, Michigan, Tennessee, and West Virginia, did not have any of the laws in place.50 For a detailed discussion of the relationship between domestic violence and housing instability, see Issue 3: Effects of Homelessness on Families and Children.

Policies Reducing Homeless Families’ Risk for Food Insecurity

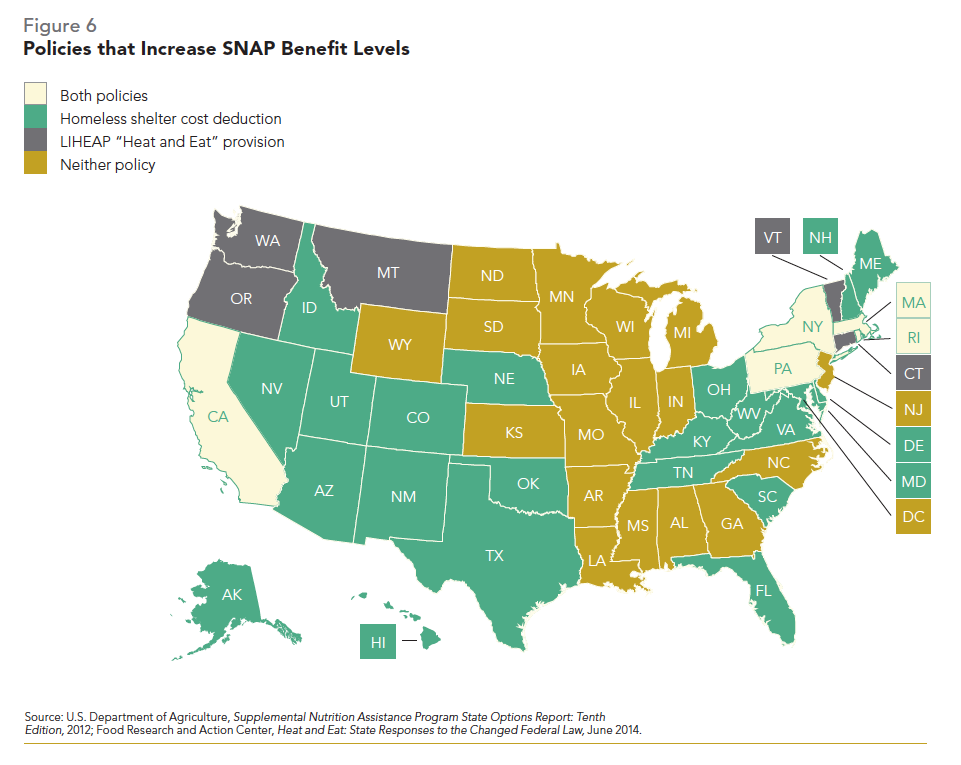

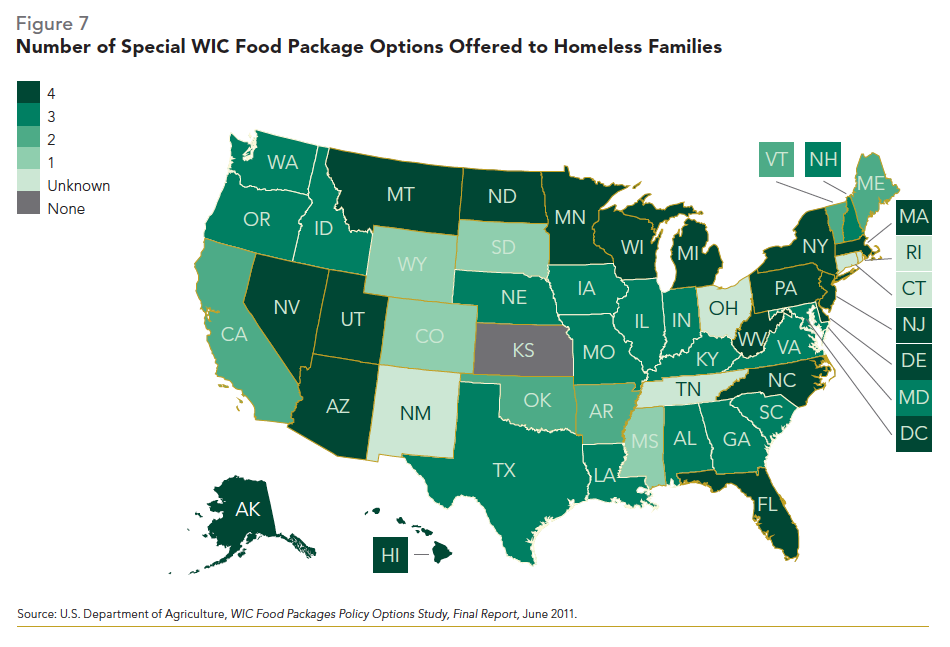

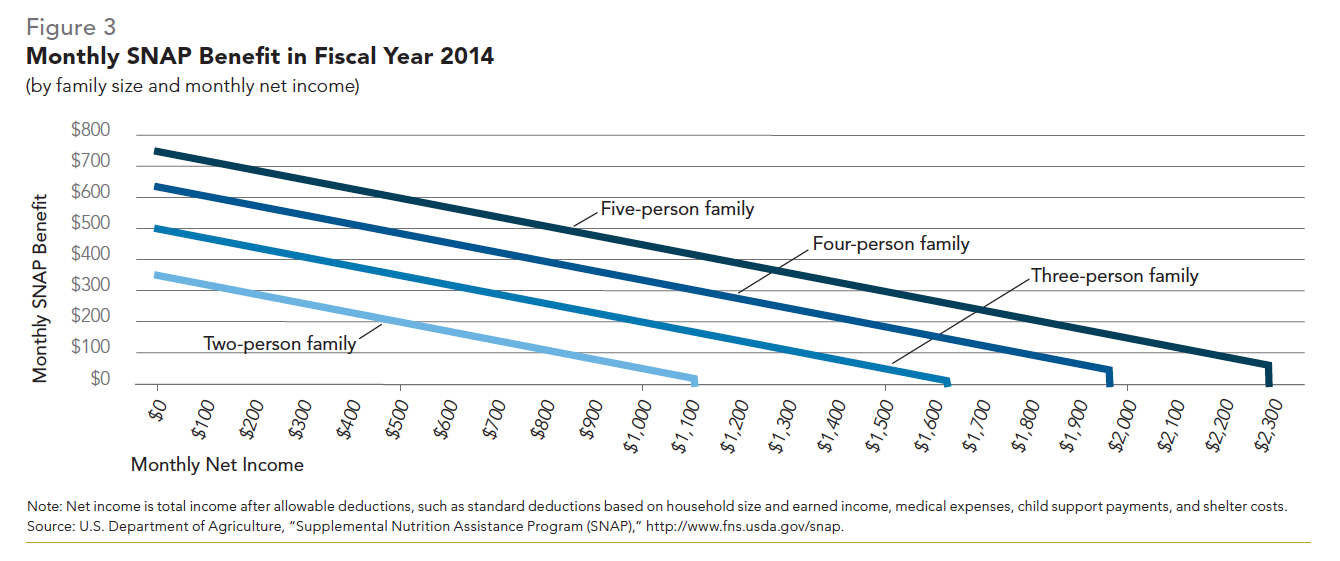

Families in poverty experience high levels of food insecurity, which the U.S. Department of Agriculture defines as limited or unstable availability of adequate amounts of nutritious food. Given their limited financial resources and housing instability, homeless families are at an even greater risk of becoming food insecure. The two primary federal mainstream programs that address food insecurity among homeless families are the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as the Food Stamp Program) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC).51 By freeing up resources to pay for other necessities, including housing, these programs reduce the likelihood that a poor family will become homeless and support homeless families in gaining economic and housing stability. For this fifth and last policy indicator, the State Policy Ranking examines two federal SNAP policies and one federal WIC policy that states can implement to reduce homeless families’ risk for food insecurity.

The amount a family receives in SNAP benefits is based on their income. The first SNAP policy allows families without permanent residences who are applying for SNAP to reduce their reported net monthly income by using one of two deductions that account for shelter costs. Qualifying shelter expenditures range from formal fees at emergency shelters to informal payments to double up at a friend, family member, or other non-relative’s residence. All states offer the option of deducting excess shelter costs that exceed 50% of a family’s income, but for some homeless families it is more beneficial to use the standard $143 deduction because documentation is not required, a policy that is offered by only 27 states.52

The second SNAP policy, the “Heat and Eat” provision, is an additional deduction that can increase SNAP benefits. Households that receive energy cost assistance through the federal Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) are automatically eligible for a higher level of SNAP benefits in states that utilize “Heat and Eat” because they can deduct a Standard Utility Allowance from their reported income when applying for benefits. The Agricultural Act of 2014 raised the minimum amount of energy assistance each household must receive to participate in the program and, as of June 2014, just ten states have committed to increasing LIHEAP aid in order to maintain previous SNAP benefit levels.53

For low-income pregnant mothers and families with young children, the WIC policy examined by the State Policy Ranking gives states discretion to provide food packages specifically tailored to meet the unique needs of homeless families who do not have access to sanitary water, cooking facilities, refrigeration, or sufficient storage. Most states provide tailored packages for at least one of these conditions and were awarded partial credit, but only 19 states received full credit for accounting for all four needs.56

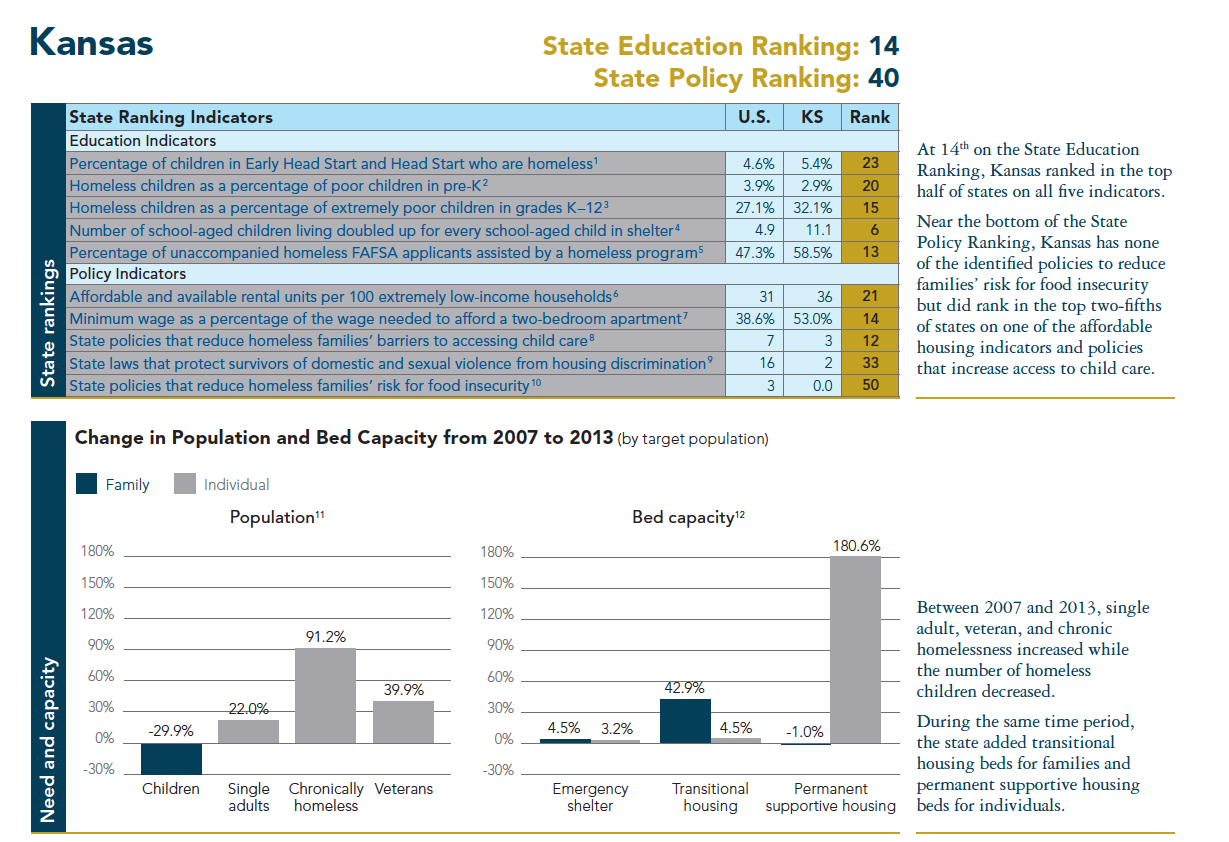

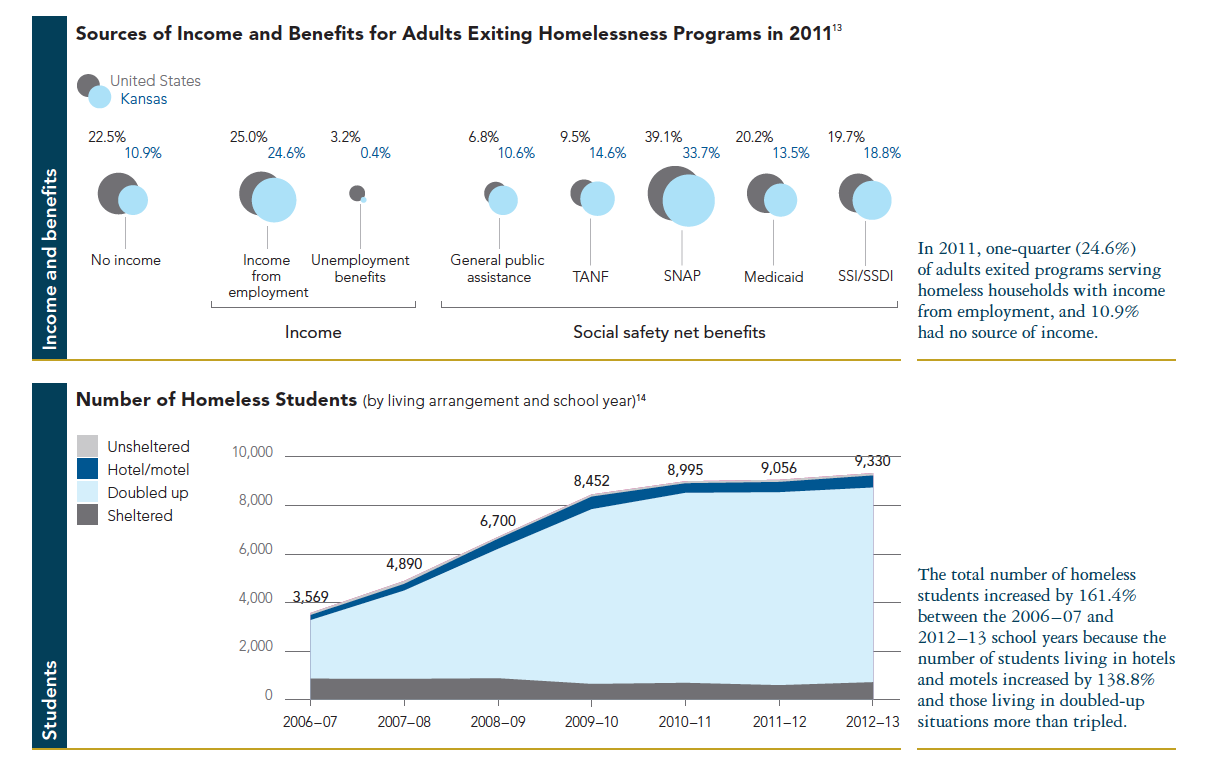

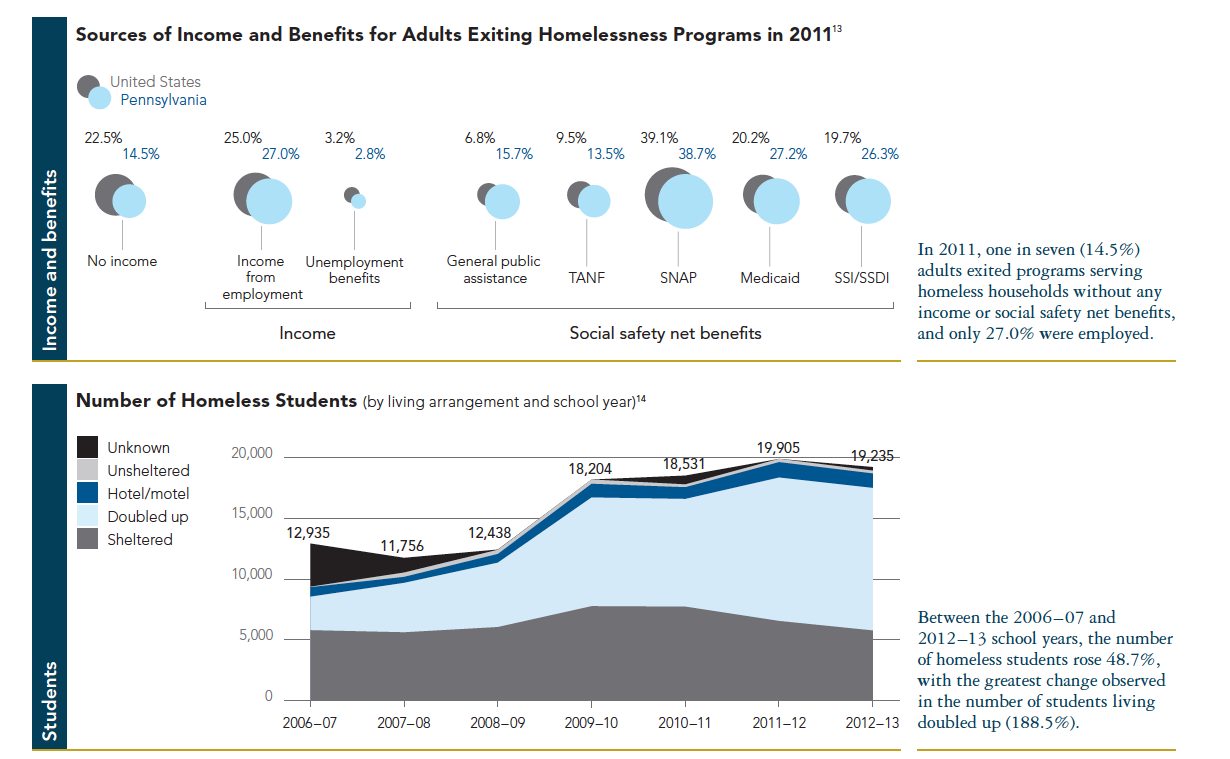

For this fifth policy indicator, three states—Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania—enacted all three policies that reduce homeless families’ risk for food insecurity (Example 10). Conversely, Kansas instituted none of the policies; Colorado, Mississippi, South Dakota, and Wyoming have instituted the WIC food packing provision to accommodate only one of the four special needs of homeless families.57 For a detailed discussion on the effects of food insecurity on homeless families, see Issue 3: Effects of Homelessness on Families and Children.

Example 10 Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania’s Food Security Policies

Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania tie for first place on the State Policy Ranking food insecurity indicator. All three states provide special packaging of WIC foods that account for the four identified needs of homeless families. To increase SNAP benefits, all three also offer homeless families the option to use a standard deduction to account for housing expenses or the Standard Utility Allowance through the “Heat and Eat” provision.54 Two weeks after the passage of the Agricultural Act of 2014, New York became one of the first states to commit to continuing the “Heat and Eat” provision. Projections showed that by allocating an estimated $6 million to households through the LIHEAP provision, New York could preserve $457 million in SNAP funding for 300,000 people. Massachusetts and Pennsylvania pledged their commitments in March of 2014, ensuring the continuation of increased benefit levels for 163,000 and 400,000 residents, respectively.55 These three vital policies are beneficial for low-income families, but additional policy initiatives are needed in order to further reduce food insecurity.

Conclusion

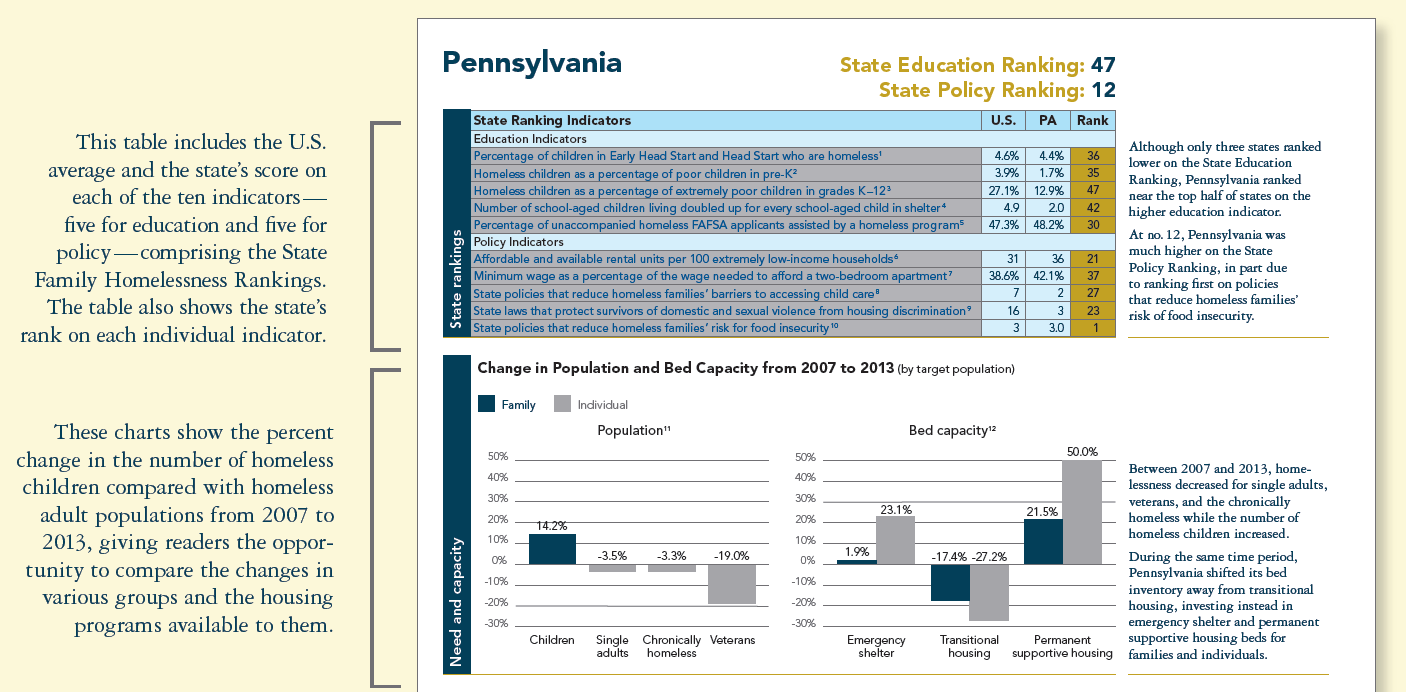

ICPH created the State Family Homelessness Rankings to serve as a guide for states in preventing and reducing family homelessness. ICPH encourages a wide range of stakeholders to review their state’s performance on each of the detailed education and policy tables (Tables 3 and 5). Placing at the top of the rankings should not be interpreted as a sign that additional effort is not needed. In the State Policy Ranking, for example, top-ranked Massachusetts places first on two indicators and in the top ten on another, but the state falls in the middle and bottom fifth on the two other indicators (Table 5). Likewise, stakeholders in those states ranking near the bottom do not necessarily need to make extensive changes to better serve homeless families. Hawaii, ranked last on the State Policy Ranking, is in the bottom ten on three indicators but in the top two-fifths on the other two indicators.

Additionally, states may have other promising policies or positive outcomes beyond those examined in the State Family Homelessness Rankings. For example, the effectiveness of state leadership in coordinating services for homeless students is critical but challenging to measure or compare across states (Example 11). While it is also not practical to include every state policy that could affect homeless children and their parents, it is important to acknowledge that a state near the bottom of the ranking may have a positive policy in place that a top-ranked state does not (Example 12).

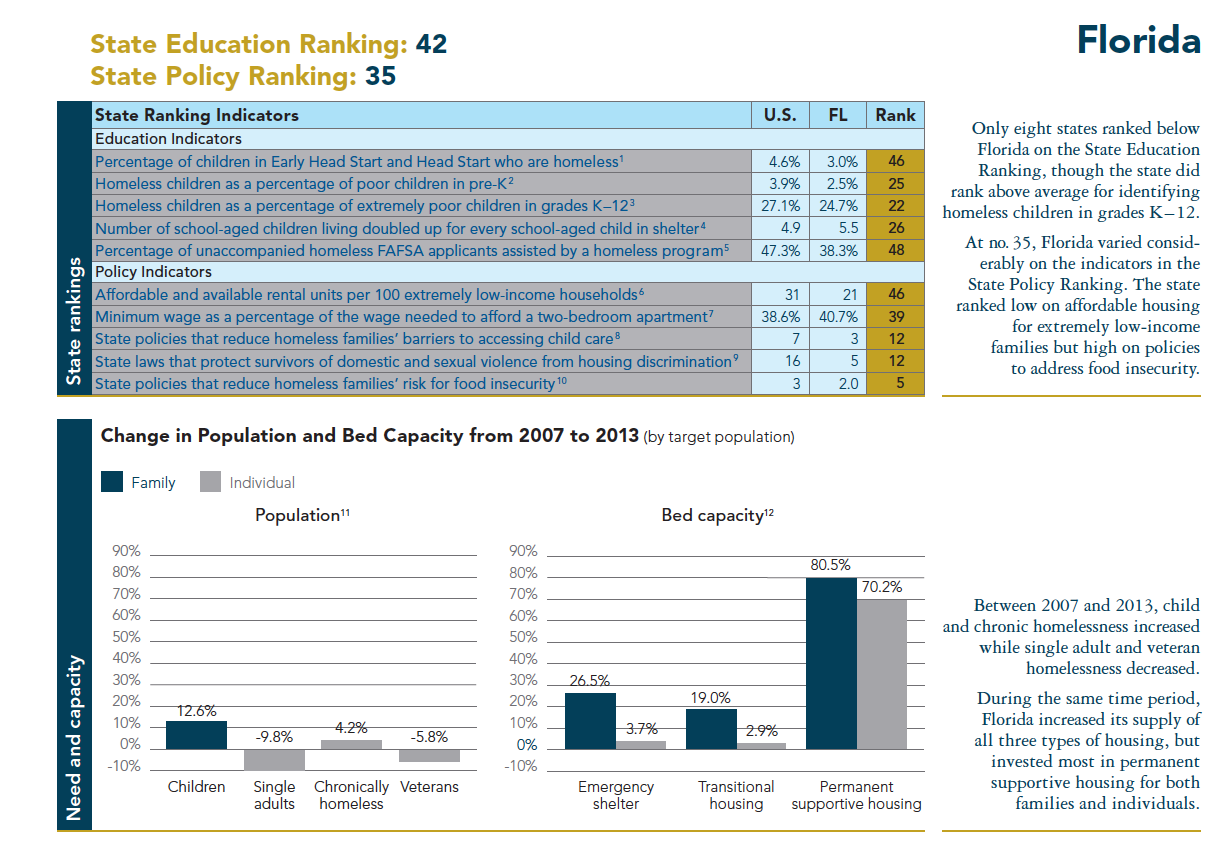

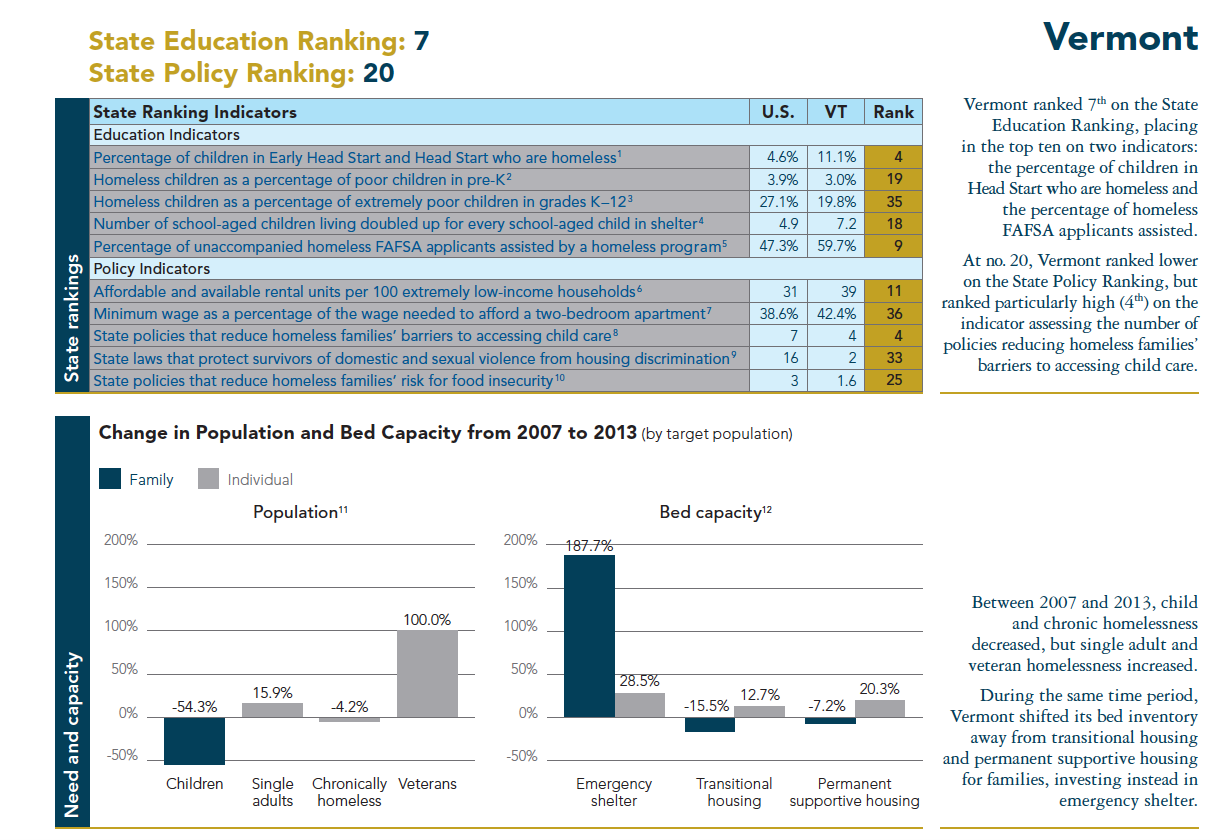

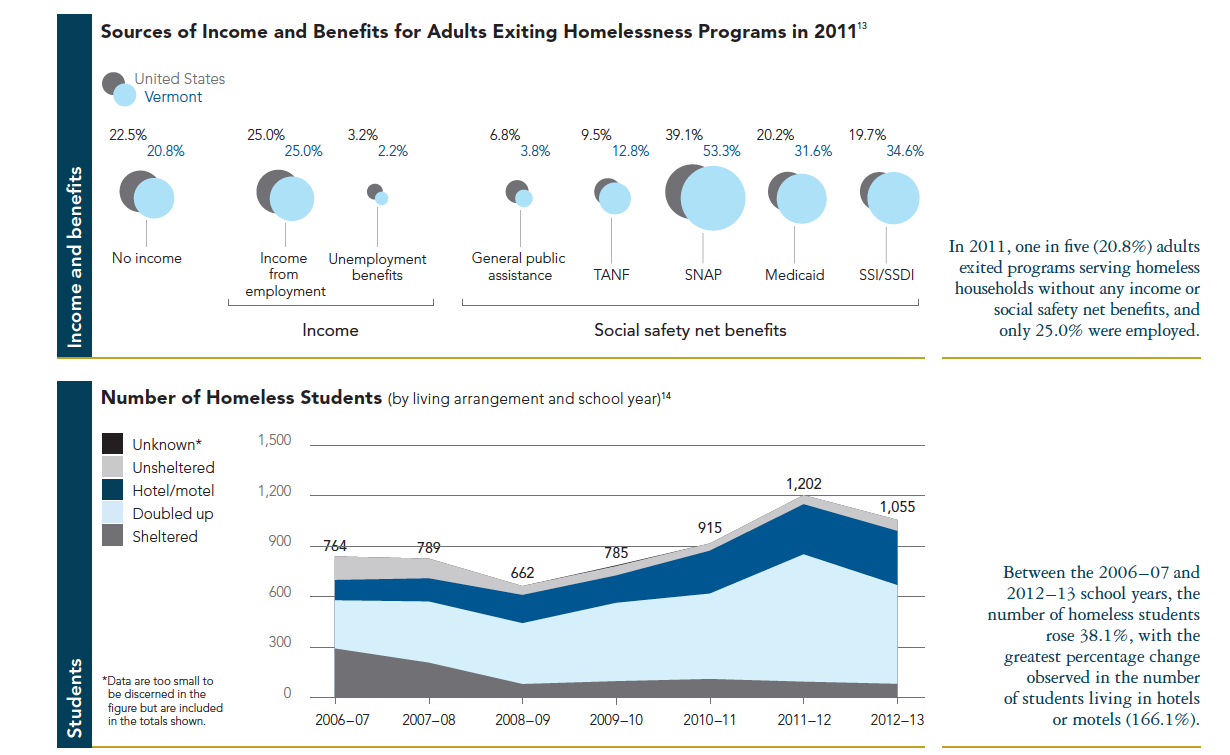

Example 11 Beyond the State Education Ranking—Florida and Vermont

Leadership at the state level—a factor in addressing family homelessness that is not directly assessed in the State Education Ranking—is paramount to ensure that local homeless liaisons are empowered with the appropriate knowledge and resources to properly identify homeless students. Despite ranking low (42nd) on the State Education Ranking, Florida has three full-time staff dedicated to coordinating the state homeless education program, which is more than the majority of states. In addition to ensuring statewide compliance with McKinney-Vento, the program staff provide guidance and technical assistance to local homeless liaisons, hosting bimonthly conference calls. Additionally, homeless students are also exempt from paying tuition at state universities in Florida, which removes a significant barrier to higher education. In contrast, while Vermont ranked high (7th) on the State Education Ranking, the U.S. Department of Education (ED) found that in 2013, the state was not monitoring local educational agencies for their compliance with McKinney-Vento. ED also discovered that Vermont had not distributed federal Education for Homeless Children and Youth program funds prior to the start of the 2013–14 school year as required. Vermont was obligated to correct both policies within 30 days. These examples demonstrate that the State Education Ranking indicators capture only some of the necessary policies and additional positive programs in place to support homeless students.58

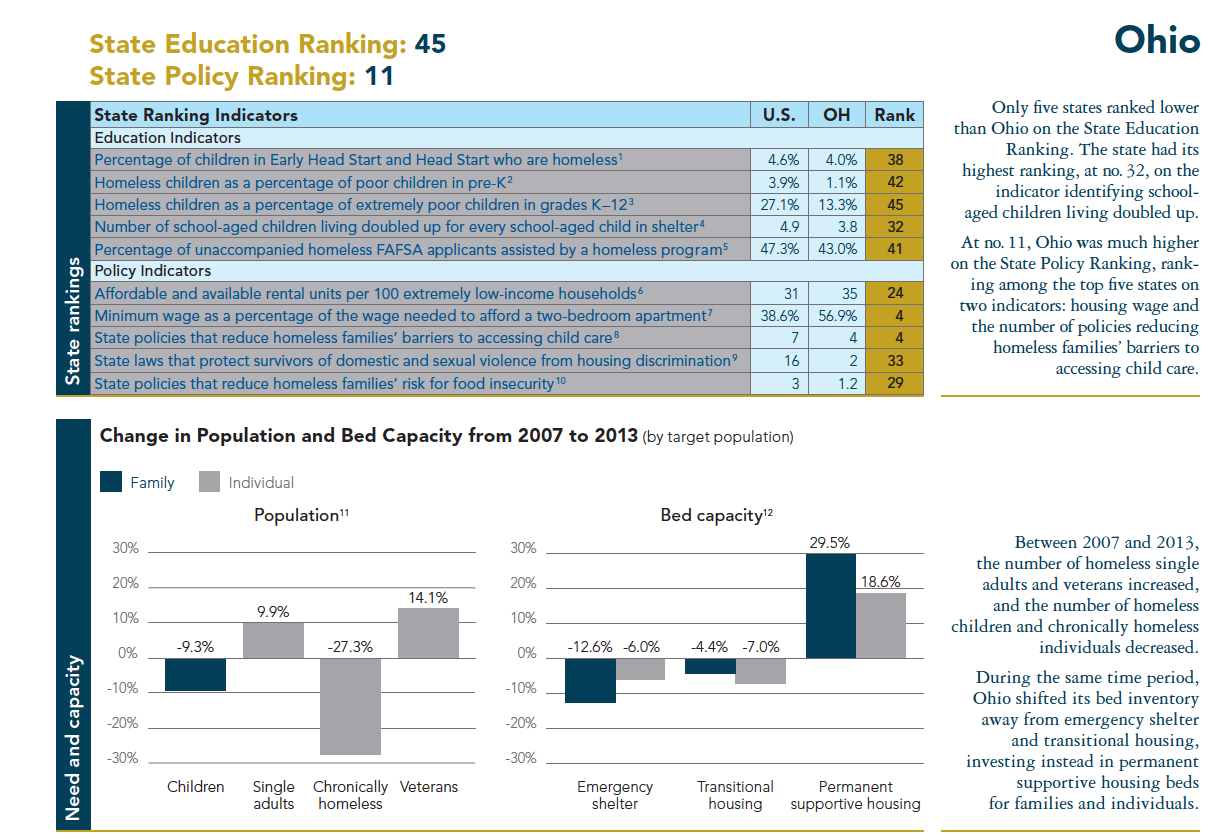

Example 12 Beyond the State Policy Ranking—Michigan and North Dakota

In addition to the homeless-specific policies and practices reflected in the State Policy Ranking indicators, there are many other policies that impact homeless families. School breakfast and lunch programs, for example, can help prevent food insecurity among homeless children. Despite ranking low (49th) on the State Policy Ranking, Michigan state law requires that all K–12 public schools participate in the National School Lunch Program. Schools where more than 20% of students receive free or reduced price lunch must participate in the School Breakfast Program as well. During the 2011–12 school year, Michigan was one of the first three states to implement the Community Eligibility Provision, a federal option to provide free breakfast and lunch to all students in high-poverty schools and districts. To support the programs, Michigan is one of the 26 states that provide additional state funding to supplement federal aid. North Dakota, in contrast, ranks high (5th) on the State Policy Ranking but does not have laws that mandate school breakfast or lunch participation, nor does it provide supplementary state funding. The Food Research and Action Council ranked states based on the percent of students participating in the school lunch and breakfast programs in School Years 2011–12 and 2012–13; North Dakota ranked 32nd and 35th, respectively. These examples illustrate that state policy environments are shaped by a variety of laws and policy choices beyond those included in the State Policy Ranking.59

Supporting the self-sufficiency of homeless families today—and preventing families from becoming homeless tomorrow— requires the time, attention, and resourcefulness of a variety of stakeholders, from service providers and educators to advocates and government officials. ICPH carefully selected the education and policy indicators included in the State Family Homelessness Rankings in order to provide specific avenues to improve the delivery and accessibility of services to homeless families, children, and youth. Ultimately, the rankings highlight states’ noteworthy social services and policies as well as areas where states should improve.

Endnotes

State Family Homelessness Rankings

1 Should federal appropriations requests be met, the Obama administration intends to end veteran homelessness by the end of 2015 and chronic homelessness in 2017; U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, Opening Doors: Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness, 2010; U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2016, February 2015.

2 Although the total number of family members was reduced by 9.2% between 2009 and 2014, this decrease was due to half (52.0%) as many unsheltered family members counted in 2014 than in 2009. The number of homeless parents and children in shelter increased 2.5% during this time period; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, The 2014 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress.

3 One indicator—minimum wage as a percentage of the wage needed to afford a two-bedroom apartment at Fair Market Rent—is also used in the National Center on Family Homelessness’ America’s Youngest Outcasts rankings; Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2013 KIDS COUNT Data Book; Foundation for Child Development, 2013 Child Well-being Index; National Center on Family Homelessness, America’s Youngest Outcasts 2014; United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Report 2013: Technical Notes; UNICEF Office of Research, Innocenti Report Card 11: Child Well-being in Rich Countries, A Comparative Overview, 2013; Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-being, 2013; Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index, 2012 State of American Well-being; Opportunity Nation, 2013 Opportunity Index; Institute for Child, Youth and Family Policy, Heller School for Social Policy and Management at Brandeis University and the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State University, Child Opportunity Index Mapping, 2014; Half in Ten, Resetting the Poverty Debate, State of the States 2013; Measure of America, American Human Development Report, the Measure of America 2013–14; National Institute for Early Education Research, The State of Preschool 2013.

4 To calculate the State Family Homelessness Rankings, each indicator was first normalized to a scale of zero to one and then averaged to create the two separate rankings. The fourth education indicator—the number of school-aged children living doubled up for every school-aged child staying in a shelter—was expressed as a percentage rather than a ratio.

5 See endnotes 4 and 6–10.

6 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012–13 Head Start Program Information Report, Survey Summary Report—State Level.

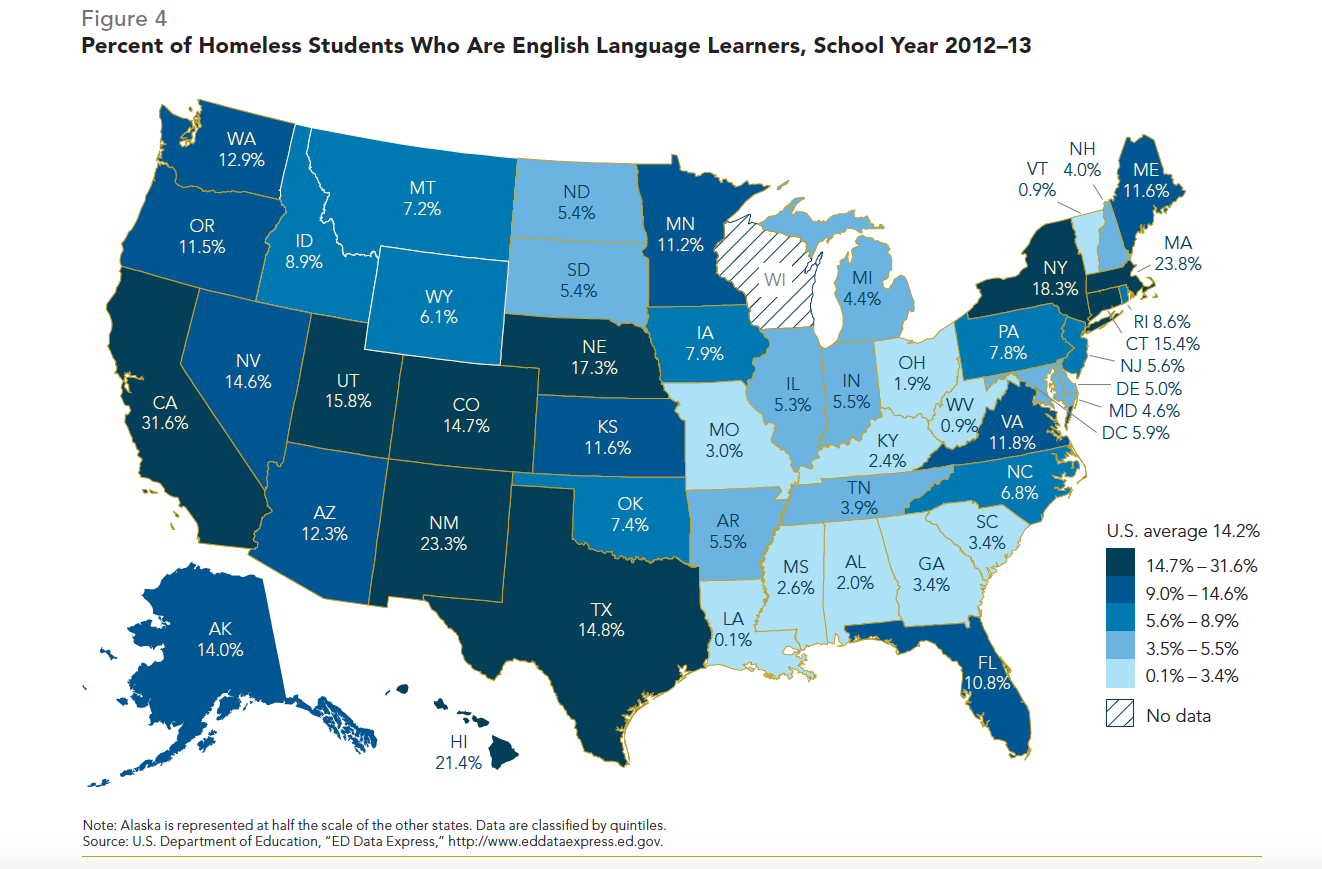

7 U.S. Department of Education, “ED Data Express,” http://eddataexpress.ed.gov; U.S. Census Bureau, 2013 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates.

8 Ibid.

9 U.S. Department of Education, “ED Data Express,” http://eddataexpress.ed.gov.

10 U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid, “Applicants with Homelessness Indicated on the FAFSA by State: 2012–13 Application Cycle” (unpublished data).

11 U.S. Census Bureau, 2013 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013 Poverty Guidelines.

12 National Institute for Early Education Research and Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Abbott Preschool Program Longitudinal Effects Study: Fifth Grade Follow-Up, March 2013; Steven Barnett, “Long-term Effects of Early Childhood Programs on Cognitive and School Outcomes,” The Future of Children Vol. 5, no. 3 (1995): 25–50; Lawrence J. Schweinhart, et al., Lifetime Effects: The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study Through Age 40 (Ypsilanti: High/Scope Press, 2005).

13 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Head Start,” http://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/hslc; Barbara Duffield, “Serving Homeless Children Through Head Start” (conference presentation, National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth, 21st Annual Conference, Denver, CO, November 14, 2009); Family Housing Fund, Homelessness and Its Effects on Children, 1999; Head Start Act, U.S. Code 9801 (2007).

14 U.S. Department of Education, Consolidated State Performance Reports, School Year 2012–13; U.S. Department of Education, Digest of Education Statistics 2013; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Characteristics and Dynamics of Homeless Families with Children, 2007.

15 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012–13 Head Start Program Information Report, Survey Summary Report—State Level; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2007–08 Head Start Program Information Report, Survey Summary Report—State Level.

16 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012–13 Head Start Program Information Report, Survey Summary Report—State Level.

17 U.S. Department of Education, “ED Data Express,” http://eddataexpress.ed.gov; U.S. Census Bureau, 2013 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Race to the Top—Early Learning Challenge,” http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/ecd/early-learning/race-to-the-top.

18 U.S. Department of Education, “ED Data Express,” http://eddataexpress.ed.gov; U.S. Census Bureau, 2013 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates; National Institute for Early Education Research, The State of Preschool 2013.

19 U.S. Census Bureau, 2013 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates.

20 National Center for Homeless Education, Education for Homeless Children and Youth Program Data Collection Summary, 2010–14; U.S. Government Accountability Office, Education of Homeless Students, July 2014.

21 U.S. Conference of Mayors, Hunger and Homelessness Survey, December 2013.

22 Ralph da Costa Nunez and Matthew Adams, “Primary Stakeholders’ Perspectives on Services for Families without Homes,” in Supporting Families Experiencing Homelessness, ed. Mary E. Haskett, Staci Perlman, and Beryl Ann Cowan (New York, NY: Springer, 2014).

23 U.S. Census Bureau, 2013 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates; University of Alaska Anchorage, The Homeless: Who and How Many?, 2014; U.S. Department of Education, Consolidated State Performance Reports, School Year 2012–13.

24 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013 Poverty Guidelines; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Characteristics and Dynamics of Homeless Families with Children, 2007.

25 State data on the number of extremely poor children in pre-kindergarten are not available; U.S. Department of Education, “ED Data Express,” http://eddataexpress.ed.gov; U.S. Census Bureau, 2013 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates.

26 U.S. Department of Education, Consolidated State Performance Reports, School Year 2012–13.

27 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, HUD’s Continuum of Care Homeless Assistance Programs—Housing Inventory Chart Report, 2005–14.

28 U.S. Department of Education, “ED Data Express,” http://eddataexpress.ed.gov.

29 U.S. Census Bureau, 2013 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Table A–4: Employment Status of the Civilian Population 25 Years and Over by Educational Attainment, 2013; Civic Enterprises, The Silent Epidemic: Perspectives of High School Dropouts, March 2006.

30 U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid, “Applicants with Homelessness Indicated on the FAFSA by State: 2012–13 Application Cycle” (unpublished data).

31 U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid, “Applicants with Homelessness Indicated on the FAFSA by State: 2012–13 Application Cycle” (unpublished data); National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth, College Access and Success for Students Experiencing Homelessness, A Toolkit for Educators and Service Providers, June 2013.

32 See endnotes 4 and 33–37.

33 National Low Income Housing Coalition, Housing Spotlight—The Affordable Rental Housing Gap Persists, August 2014.

34 U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, “Changes in Basic Minimum Wages in Non-farm Employment under State Law: Selected Years 1968 to 2013,” http://www.dol.gov/whd/ state/stateMinWageHis.htm; National Low Income Housing Coalition, Out of Reach 2013; Fair Labor Standards Act, U.S. Code 29 (1938) § 201.

35 As a final version of Alaska’s Fiscal Years 2014–15 state plan could not be obtained, a draft version was used instead; ICPH analysis of Child Care and Development Fund state plans for Fiscal Years 2014–15; Urban Institute, The CCDF Policies Database Book of Tables: Key Cross-state Variations in CCDF Policies as of October 1, 2012, November 2013.

36 National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty, There’s No Place Like Home: State Laws that Protect Housing Rights for Survivors of Domestic and Sexual Violence, 2013.

37 U.S. Department of Agriculture, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program State Options Report: Tenth Edition, 2012; Food Research and Action Center, Heat and Eat: State Responses to the Changed Federal Law, June 2014; U.S. Department of Agriculture, WIC Food Packages Policy Options Study, Final Report, June 2011.

38 National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2014 State Housing Profile; U.S. Census Bureau, South Dakota—2010 Census Results: Total Population by County.

39 National Low Income Housing Coalition, Out of Reach 2013; National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2014 State Housing Profile; Housing for the Homeless Consortium, 2014 Statewide Homeless Count Results; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Unemployment Rates for States Annual Average Rankings, Year: 2013,” http://www.bls.gov/lau/ lastrk13.htm; South Dakota Secretary of State, “Election Night Results—November 4th, 2014,” http://electionresults.sd.gov.

40 U.S. Census Bureau, 2013 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Worst Case Housing Needs 2011: Report to Congress, August 2013; National Low Income Housing Coalition, Out of Reach 2014.

41 National Low Income Housing Coalition, Housing Spotlight—The Affordable Rental Housing Gap Persists, August 2014.

42 U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, “Changes in Basic Minimum Wages in Non-farm Employment under State Law: Selected Years 1968 to 2013,” http://www.dol.gov/whd/ state/stateMinWageHis.htm; National Low Income Housing Coalition, Out of Reach 2013; Council of State Governments, Minimum Wage Watch 2015.

43 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Characteristics and Dynamics of Homeless Families with Children, 2007; U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, “Changes in Basic Minimum Wages in Non-farm Employment under State Law: Selected Years 1968 to 2013,” http://www.dol.gov/whd/state/stateMinWageHis.htm; National Low Income Housing Coalition, Out of Reach 2013.

44 Massachusetts Department of Early Education and Care, Policy Statement: Children’s Records Requirements for Priority Populations, September 2010.

45 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, FY 2012 CCDF Data Tables (Preliminary Estimates, October 2013).

46 Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, Meeting the Child Care Needs of Homeless Families: How Do States Stack Up?, July 2014; Child Care Aware of America, Parents and the High Cost of Child Care: 2013; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013 Poverty Guidelines.

47 The Child Care and Development Block Grant Act of 2014, enacted in November of 2014, made it a requirement that states establish 12-month eligibility periods and provide child care assistance for at least three months while parents who have lost their jobs look for work. The other policies that were assessed remain at each state’s discretion. As a final version of Alaska’s Fiscal Years 2014–15 state plan could not be obtained, a draft version was used instead; ICPH analysis of Child Care and Development Fund state plans for Fiscal Years 2014–15; Urban Institute, The CCDF Policies Database Book of Tables: Key Cross-state Variations in CCDF Policies as of October 1, 2012, November 2013.

48 National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty, Some Facts on Homelessness, Housing, and Violence Against Women, January 2009; Ellen Bassuk, et al., “The Characteristics and Needs of Sheltered Homeless and Low-income Housed Mothers,” Journal of the American Medical Association 276, no. 8 (1996): 640–46.

49 National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty, There’s No Place Like Home: State Laws that Protect Housing Rights for Survivors of Domestic and Sexual Violence, 2013.

50 Ibid.

51 Barrett A. Lee and Meredith J. Greif, “Homelessness and Hunger,” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 49, no. 1 (2008): 3–19; Craig Gundersen, et al., “Homelessness and Food Insecurity,” Journal of Housing Economics 12 (2003): 250–72; U.S. Department of Agriculture, “Food Security in the United States: Measuring Household Food Security,” http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/measurement.aspx; U.S. Department of Agriculture, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance

52 Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, SNAP’s Homeless Shelter Deduction Can Provide Much-needed Help for Homeless Individuals and Families, 2011; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program State Options Report: Tenth Edition, 2012.

53 Food Research and Action Center, Heat and Eat: State Responses to the Changed Federal Law, June 2014.

54 U.S. Department of Agriculture, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program State Options Report: Tenth Edition, 2012; Food Research and Action Center, Heat and Eat: State Responses to the Changed Federal Law, June 2014; U.S. Department of Agriculture, WIC Food Packages Policy Options Study, Final Report, June 2011.

55 Congressional Research Service, The 2014 Farm Bill: Changing the Treatment of LIHEAP Receipt in the Calculation of SNAP Benefits, February 2014; National Center for Appropriate Technology, LIHEAP Clearinghouse, Issue Brief #5: A New Framework for “Heat and Eat,” LIHEAP and SNAP After the 2014 Farm Bill, August 2014.

56 U.S. Department of Agriculture, WIC Food Packages Policy Options Study, Final Report, June 2011.

57 Ibid.; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program State Options Report: Tenth Edition, 2012; Food Research and Action Center, Heat and Eat: State Responses to the Changed Federal Law, June 2014.

58 Florida Department of Education, “Homeless Education Program,” http://www.fldoe.org/ schools/family-community/activities-programs/homeless-edu-program.stml; U.S. Government Accountability Office, Education of Homeless Students: Improved Oversight Needed, July 2014; U.S. Department of Education, Title I Program Monitoring: Vermont Agency of Education, September 10–12, 2013.

59 Food Research and Action Center, School Breakfast Scorecard: 2012–13 School Year, January 2014; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Community Eligibility Provision Evaluation (Summary), February 2014.

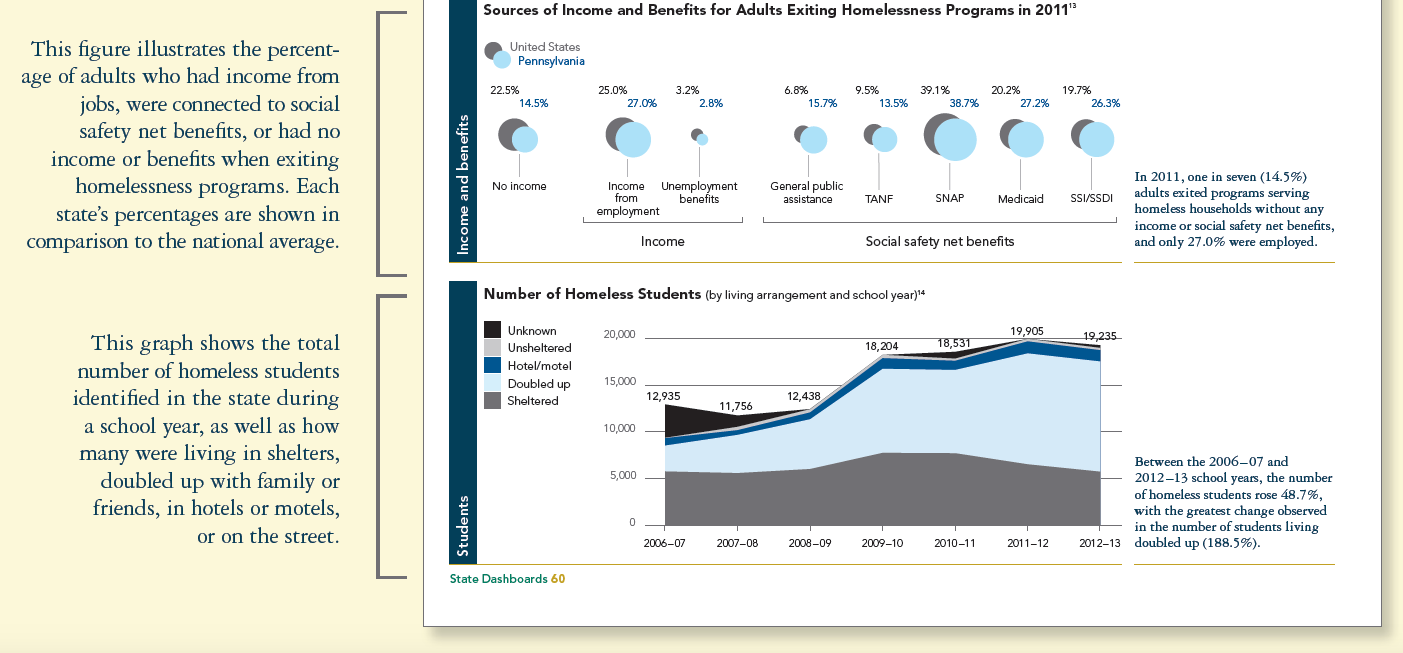

Guide to the State Dashboards

State Dashboards

Exploring Trends in Family Homelessness State by State

Endnotes

State Dashboards

1 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012–13 Head Start Program Information Report, Survey Summary Report—State Level.

2 U.S. Department of Education, “ED Data Express,” http://eddataexpress.ed.gov; U.S. Census Bureau, 2013 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates.

3 Ibid.

4 U.S. Department of Education, “ED Data Express,” http://eddataexpress.ed.gov.

5 U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid, “Applicants with Homelessness Indicated on the FAFSA by State: 2012–13 Application Cycle” (unpublished data).

6 National Low Income Housing Coalition, Housing Spotlight—The Affordable Rental Housing Gap Persists, August 2014.

7 U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, “Changes in Basic Minimum Wages in Non-farm Employment under State Law: Selected Years 1968 to 2013,” http://www.dol. gov/whd/state/stateMinWageHis.htm; National Low Income Housing Coalition, Out of Reach 2013; Fair Labor Standards Act, U.S. Code 29 (1938) § 201.

8 As a final version of Alaska’s Fiscal Years 2014–15 state plan could not be obtained, a draft version was used instead; ICPH analysis of Child Care and Development Fund state plans for Fiscal Years 2014–15; Urban Institute, The CCDF Policies Database Book of Tables: Key Cross-state Variations in CCDF Policies as of October 1, 2012, November 2013.

9 National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty, There’s No Place Like Home: State Laws that Protect Housing Rights for Survivors of Domestic and Sexual Violence, 2013.

10 U.S. Department of Agriculture, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program State Options Report: Tenth Edition, 2012; Food Research and Action Center, Heat and Eat: State Responses to the Changed Federal Law, June 2014; U.S. Department of Agriculture, WIC Food Packages Policy Options Study, Final Report, June 2011.

11 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, HUD’s CoC Homeless Assistance Programs—Homeless Populations and Subpopulations, 2007–13; National Center for Homeless Education, Education for Homeless Children and Youth Program Data Collection Summary, 2010–13; U.S. Department of Education, “ED Data Express,” http://www.eddataexpress.ed.gov.

12 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, HUD’s CoC Homeless Assistance Programs—Housing Inventory Chart Report, 2007–13.

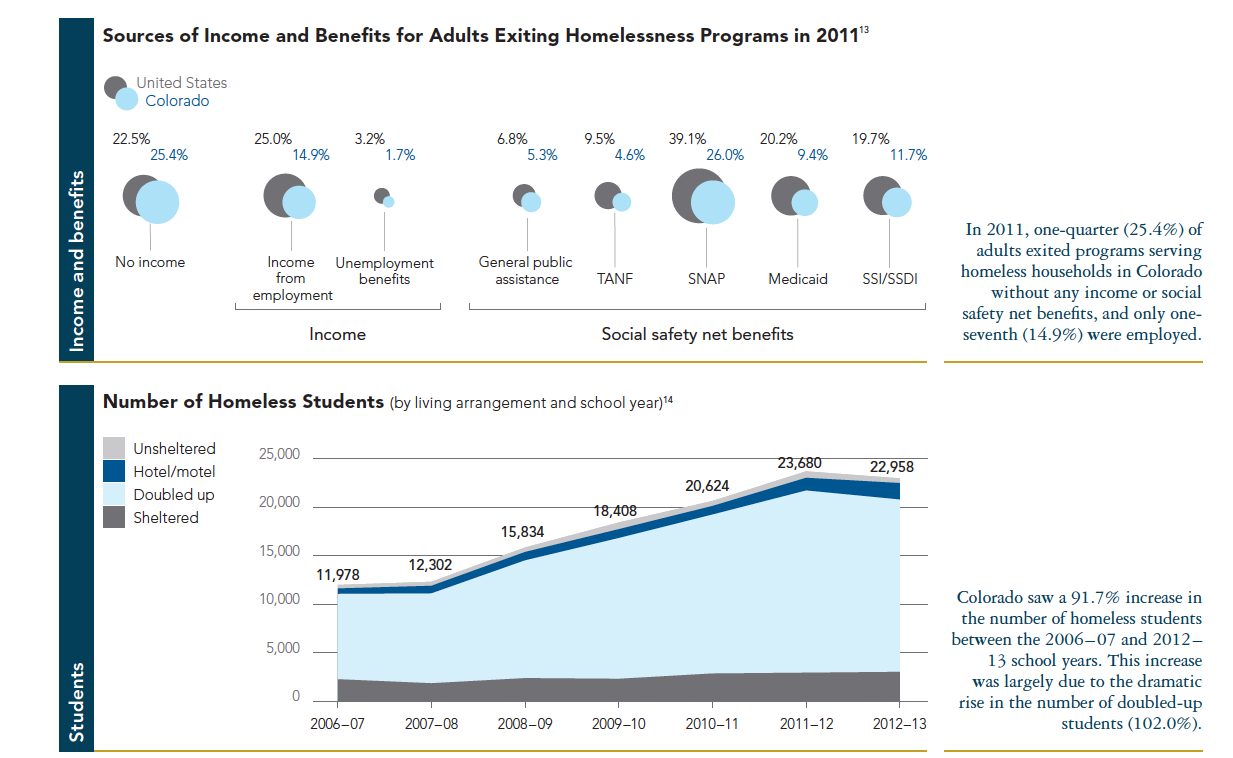

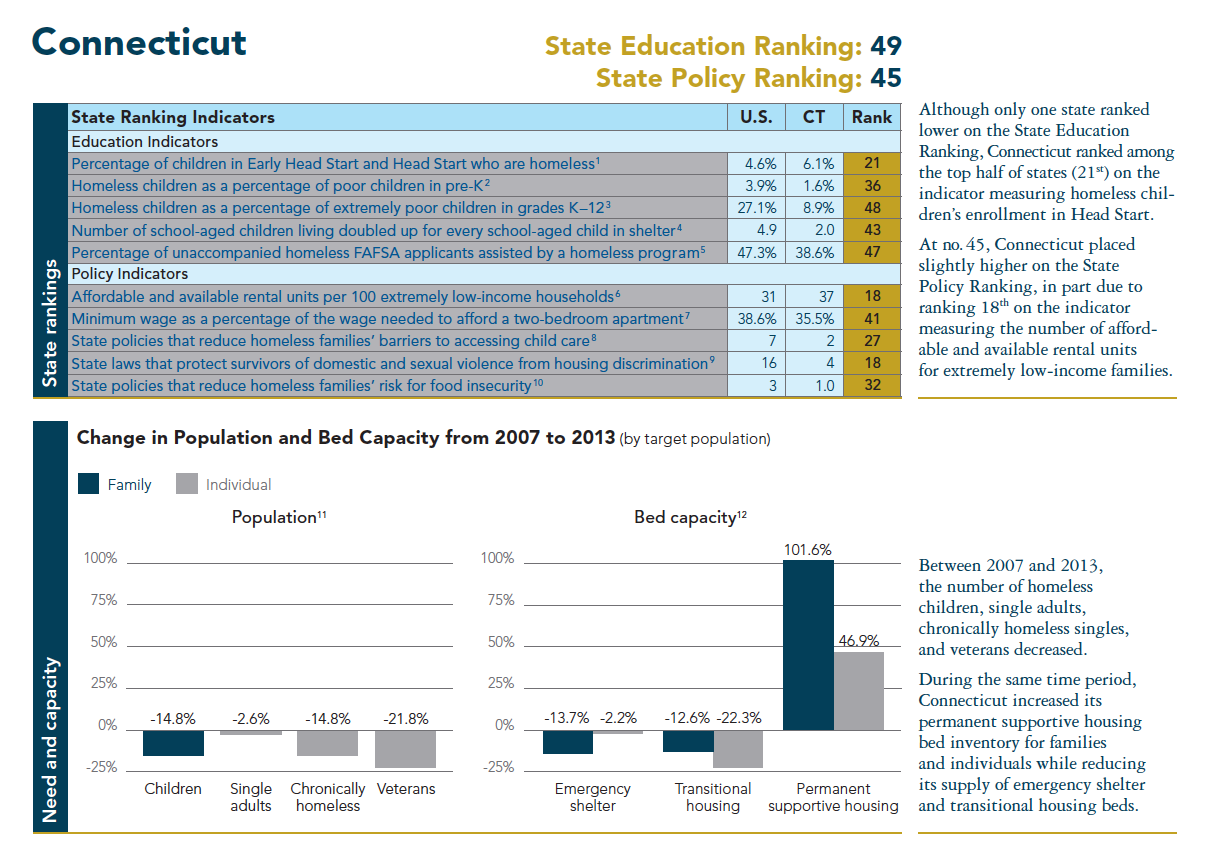

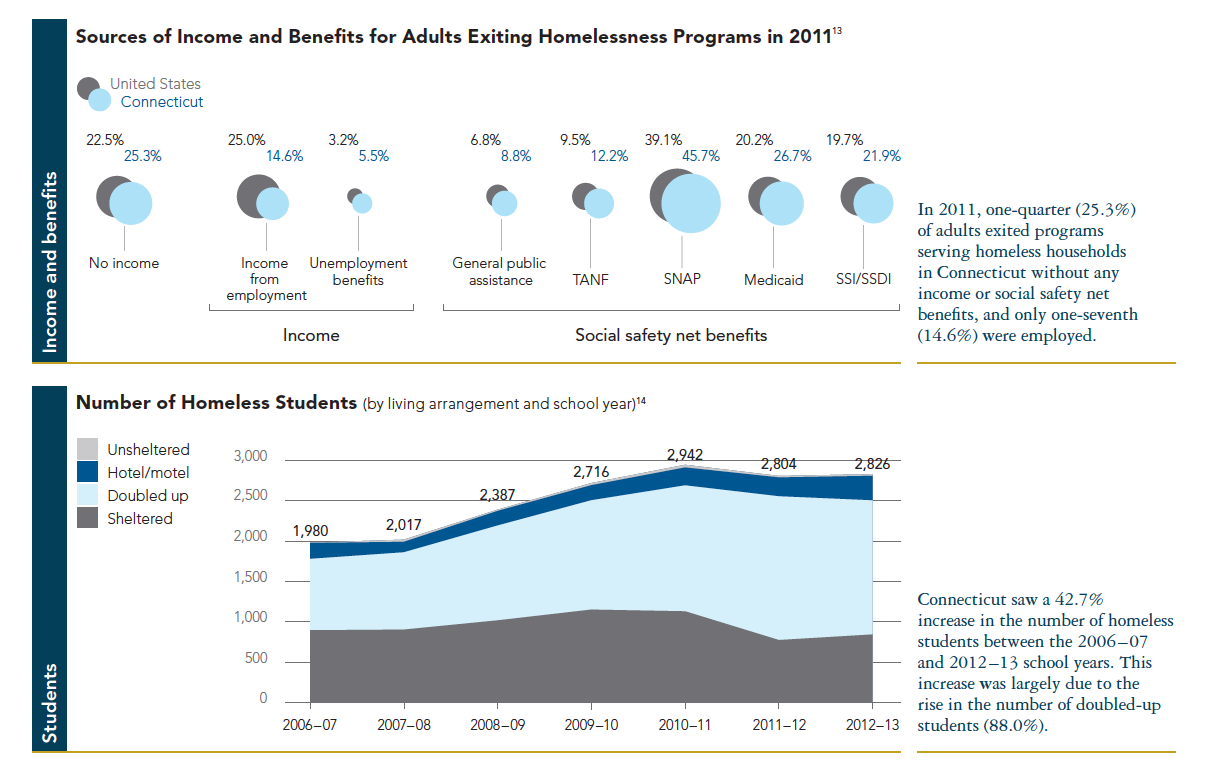

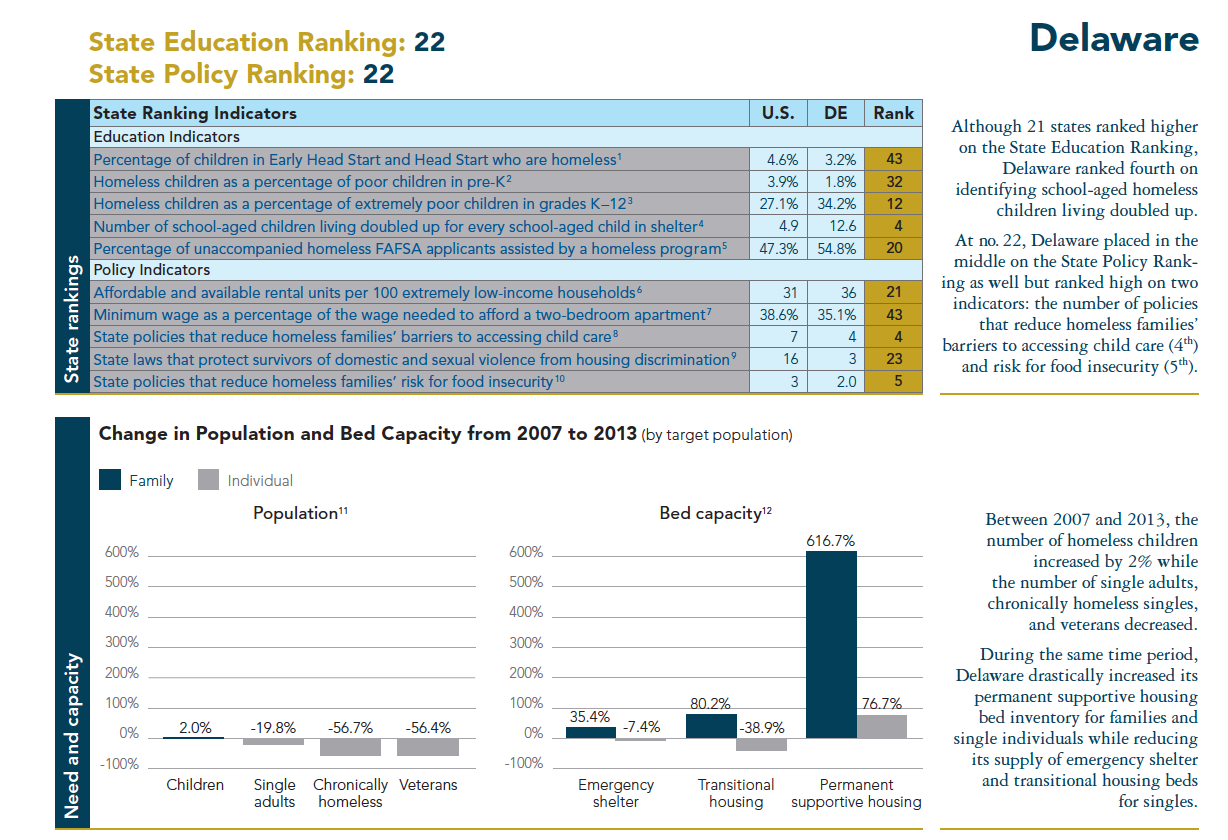

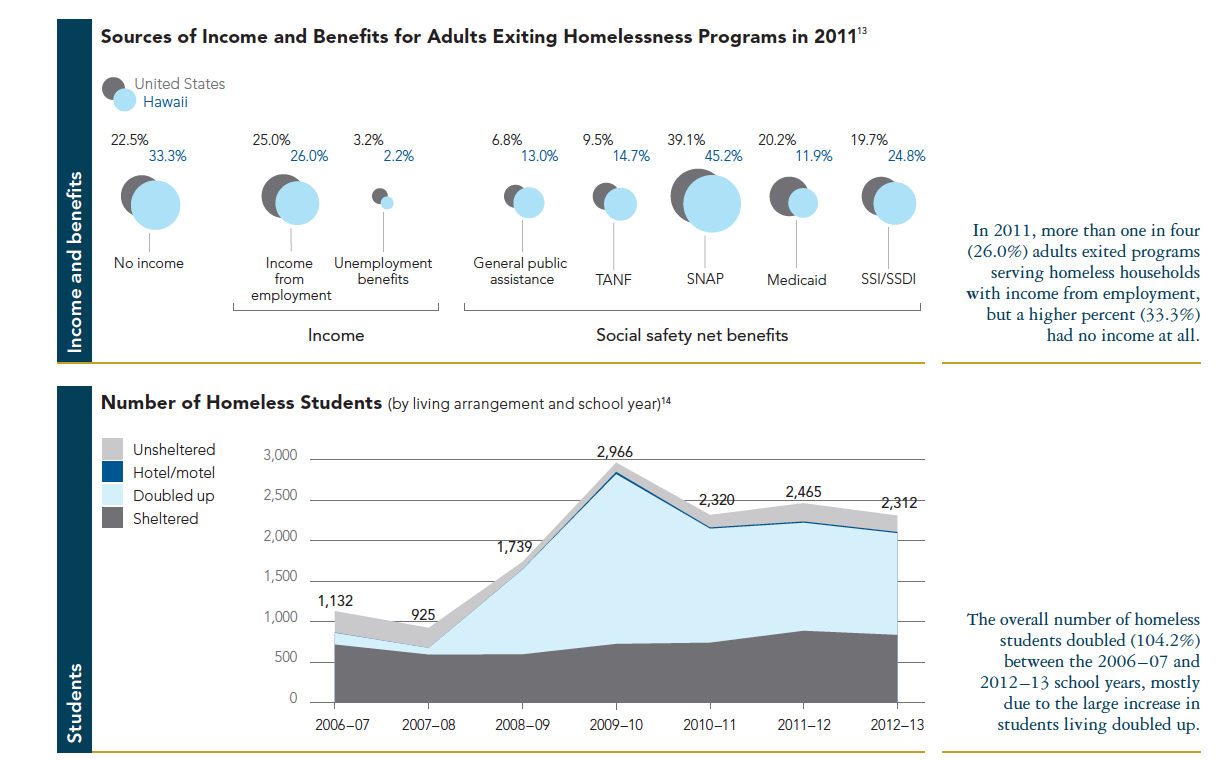

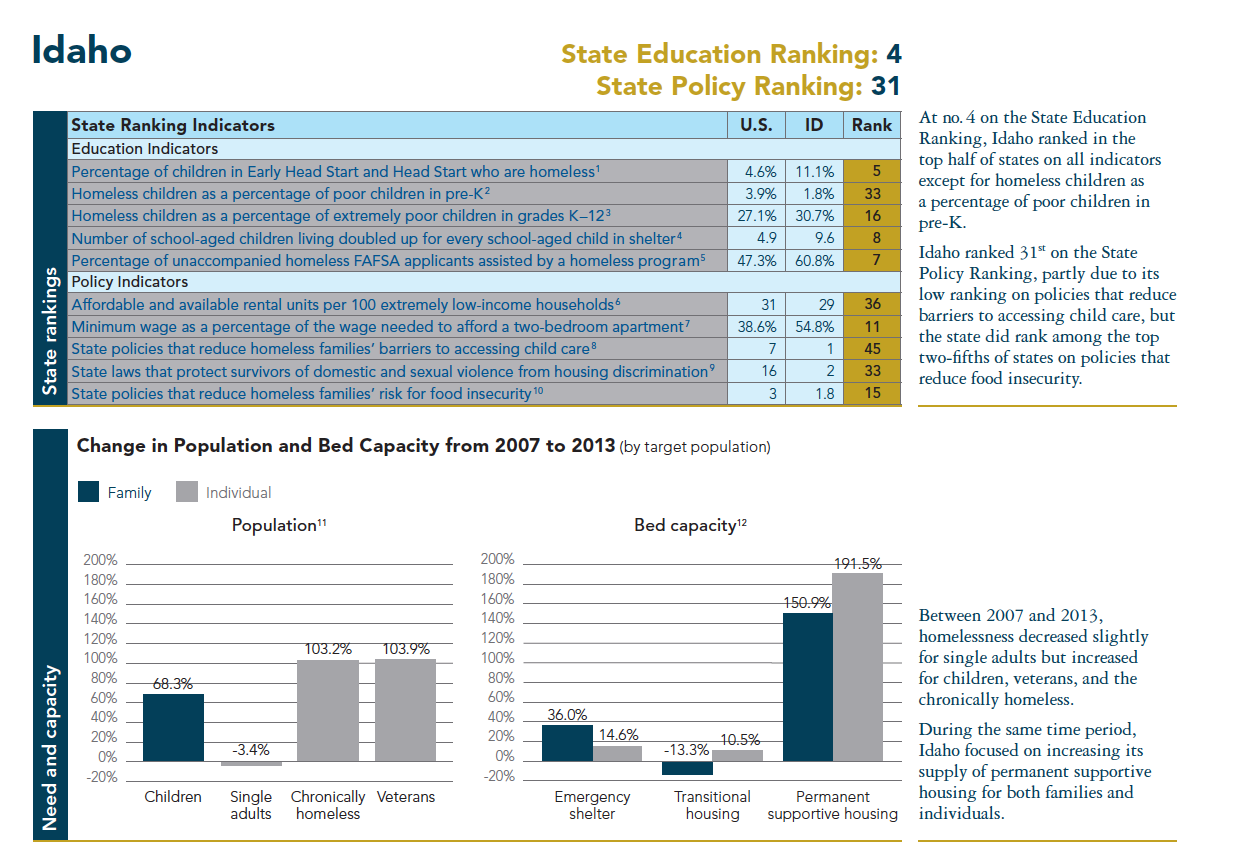

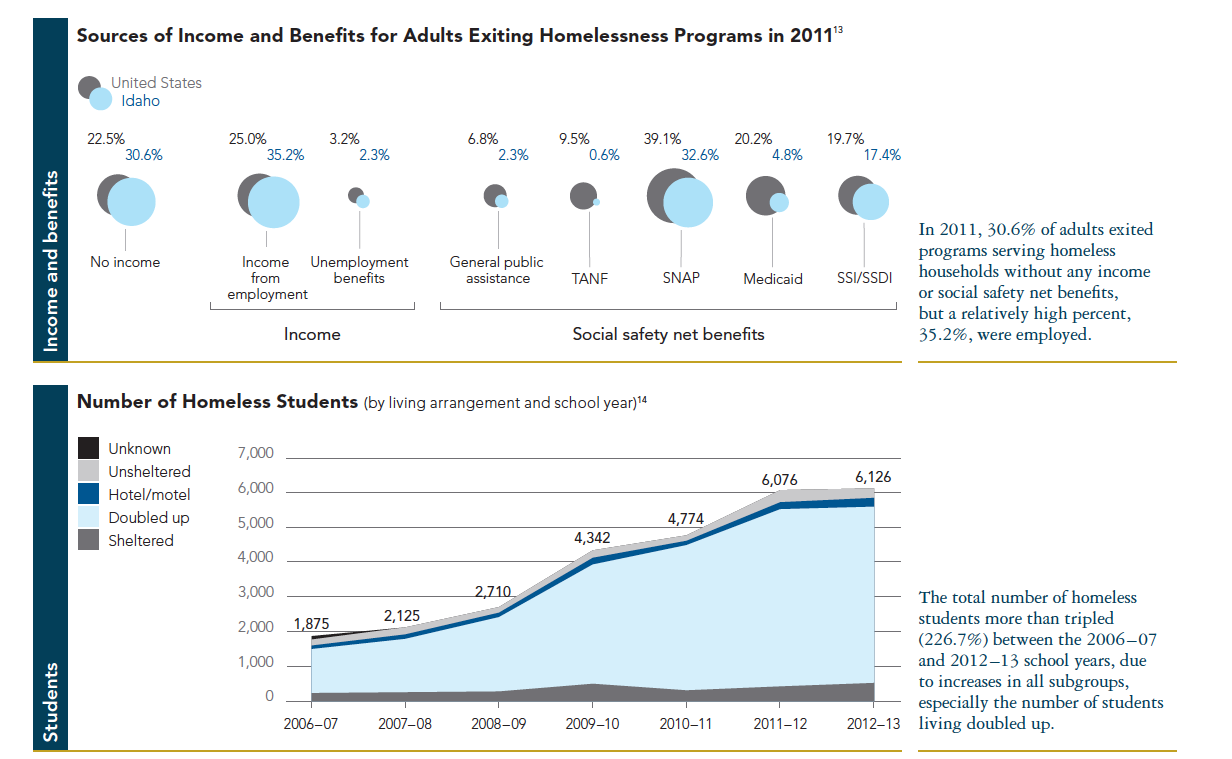

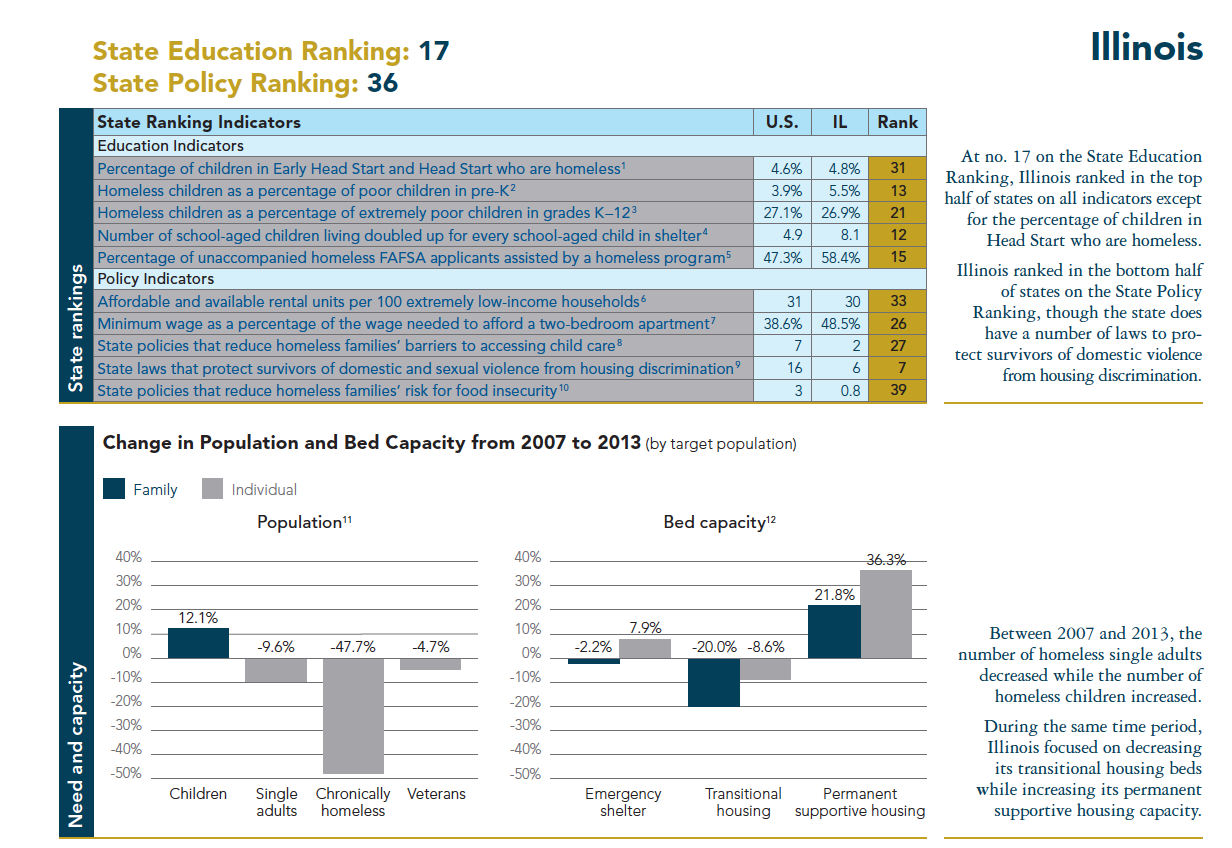

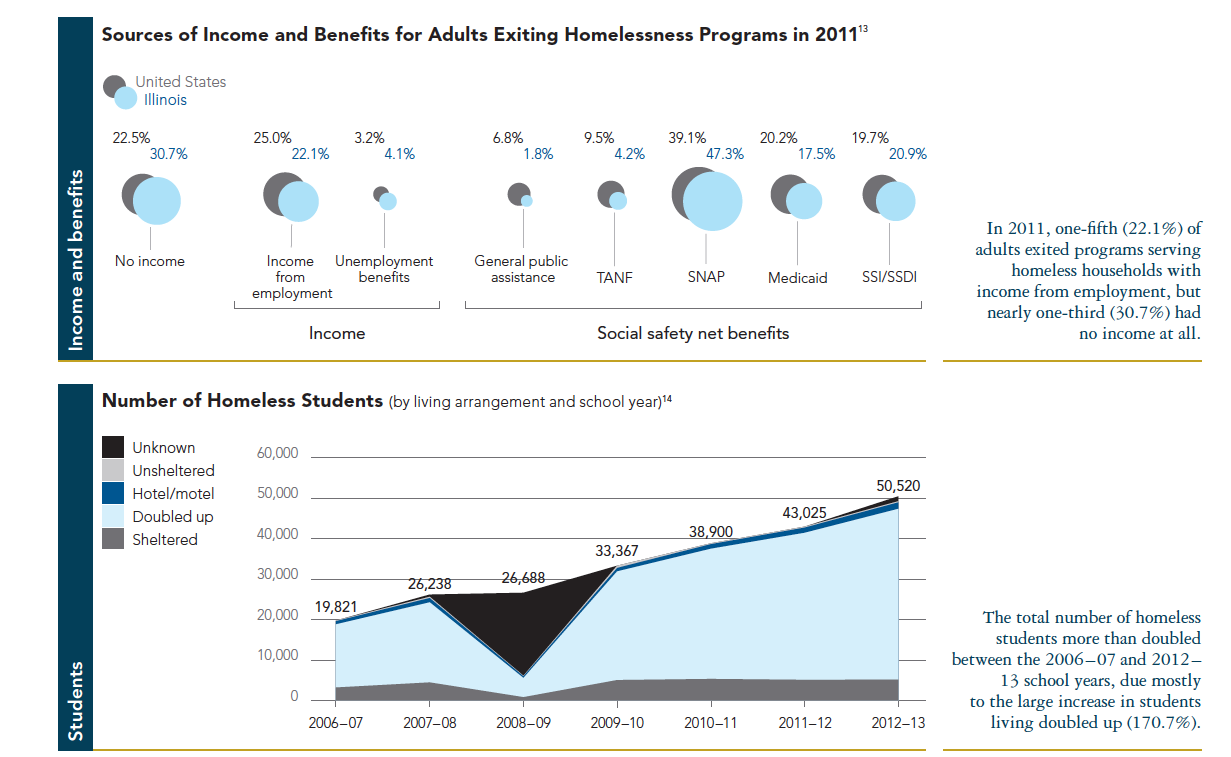

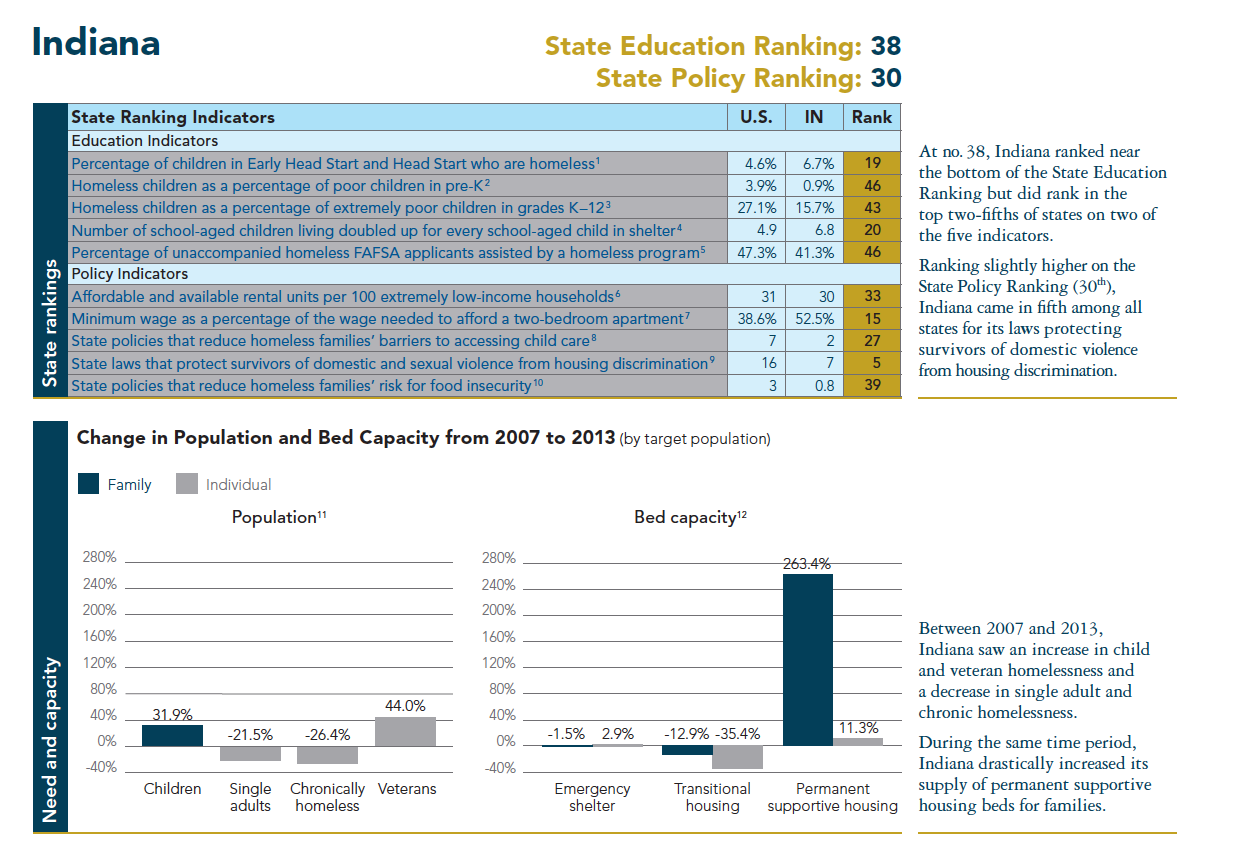

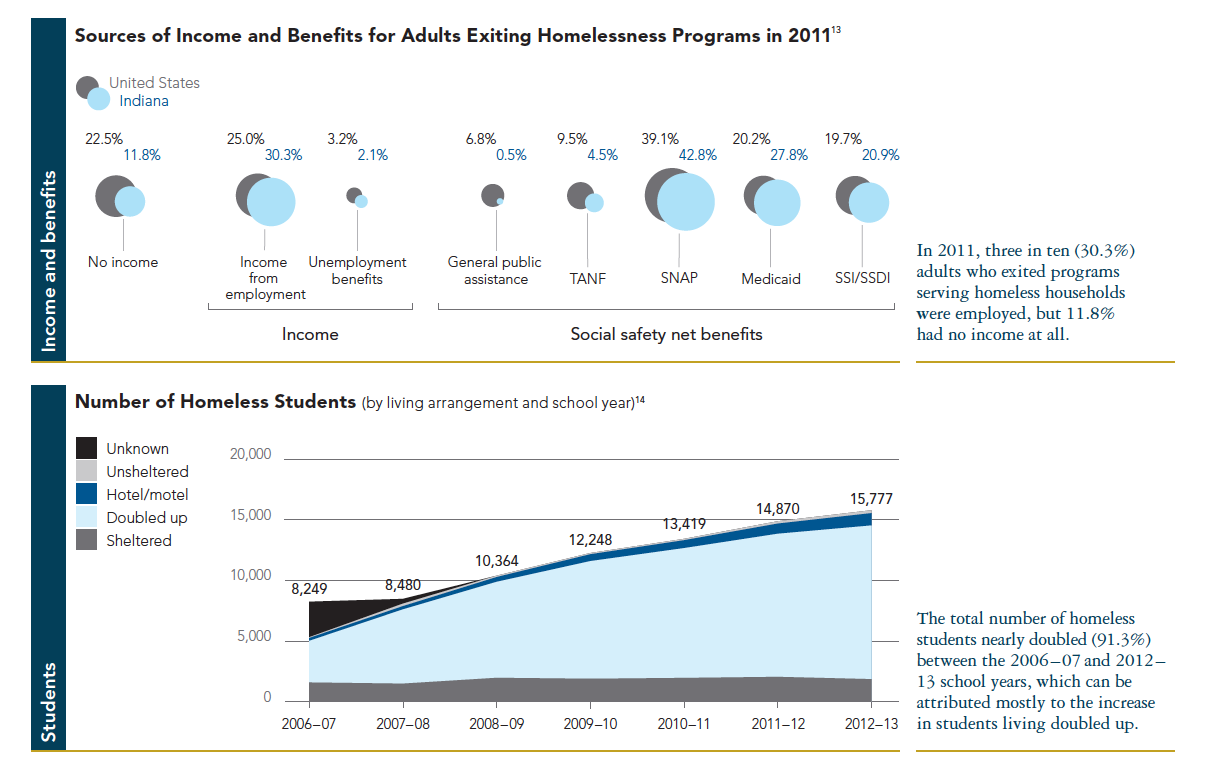

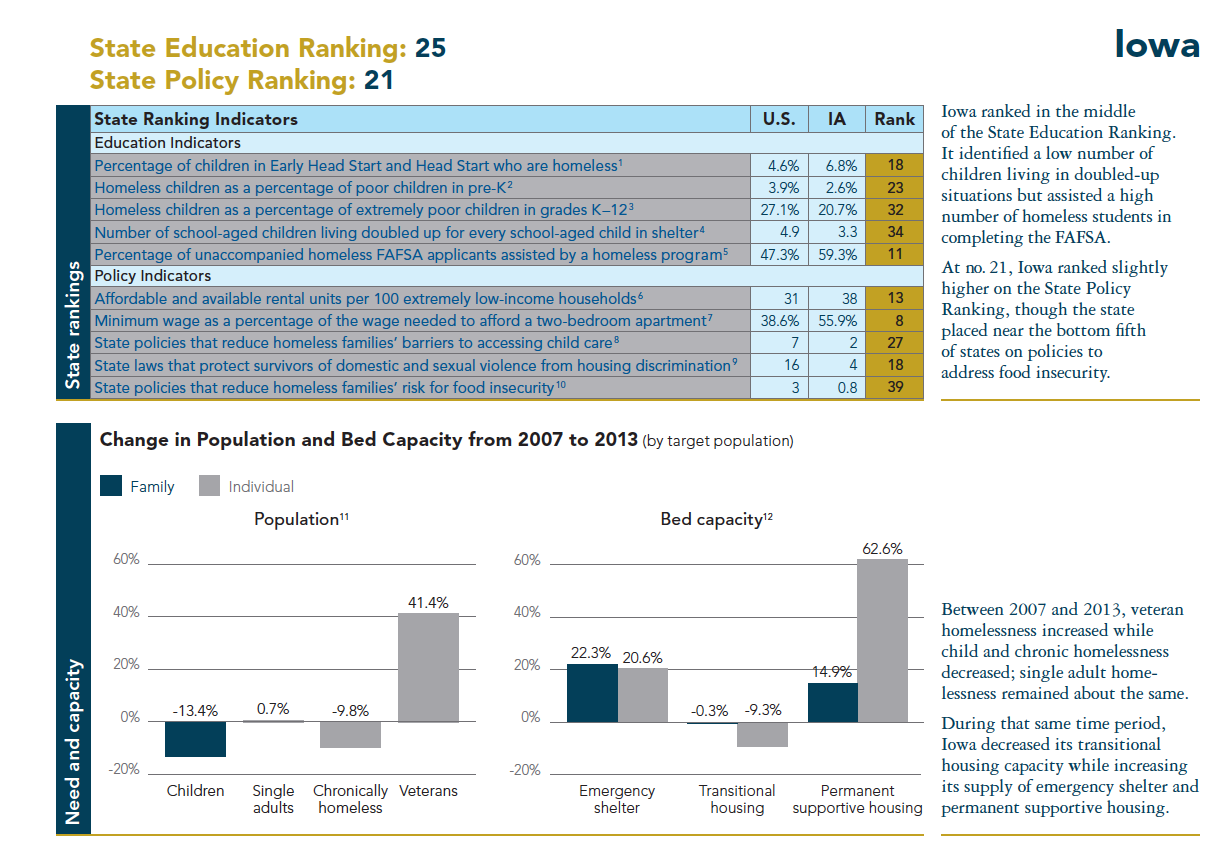

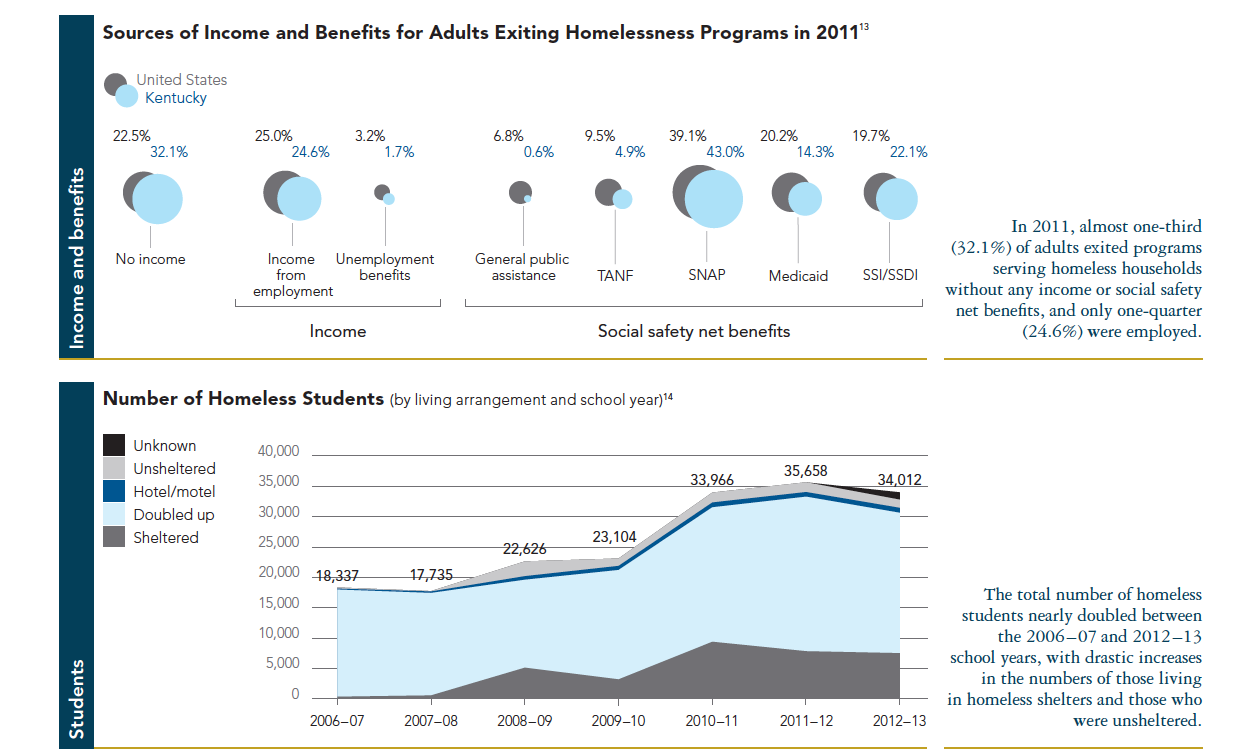

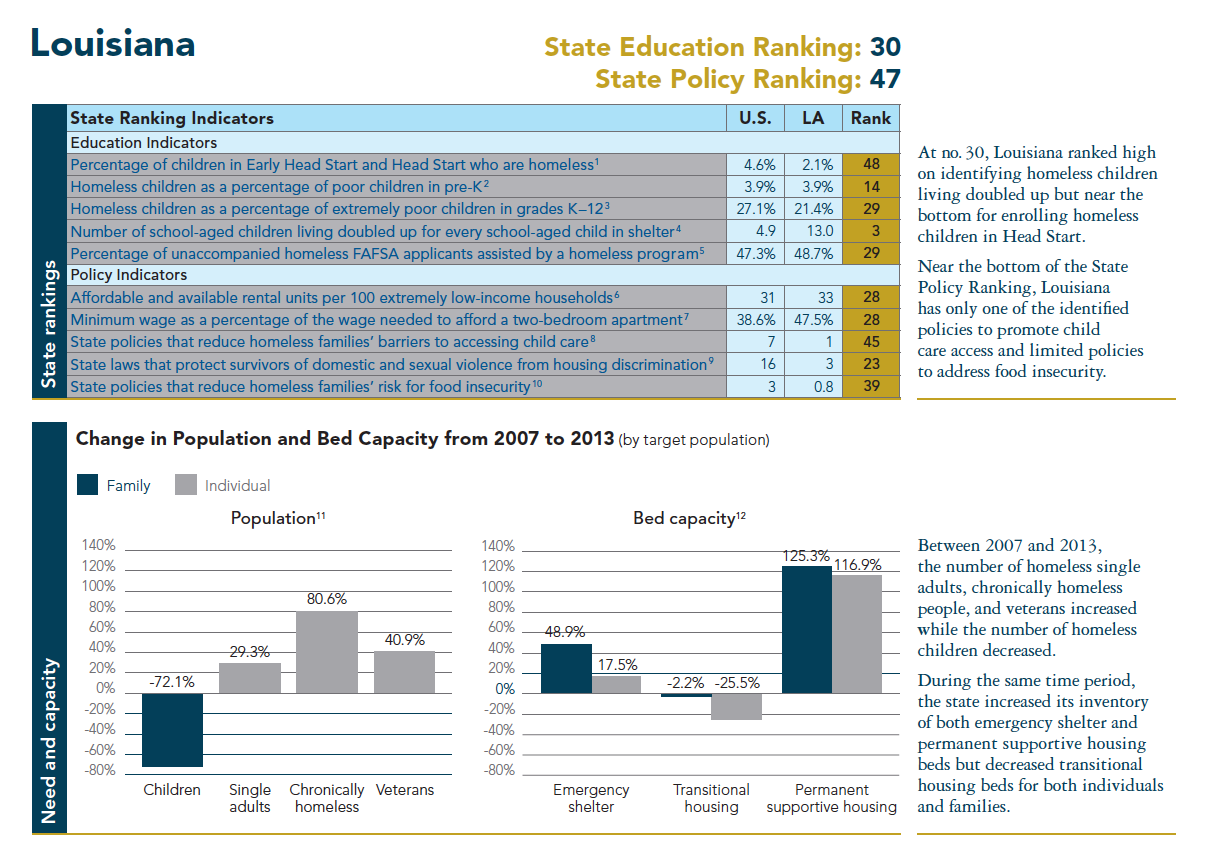

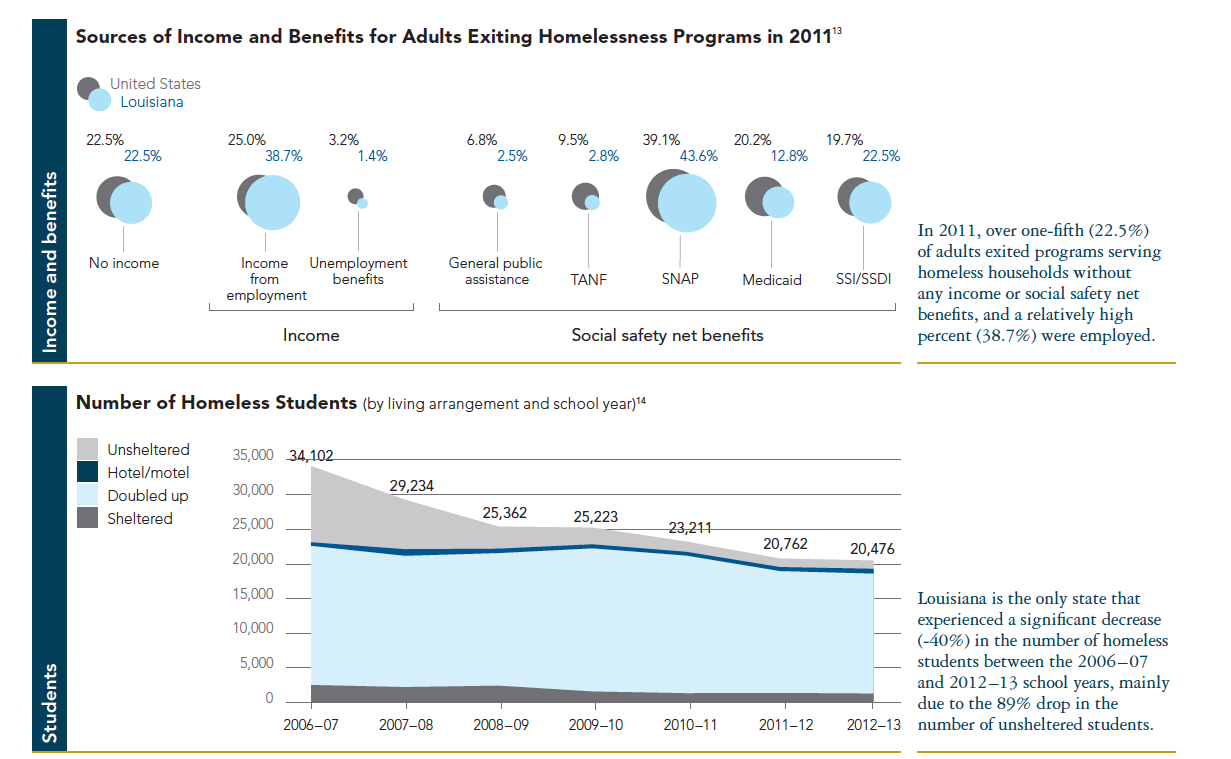

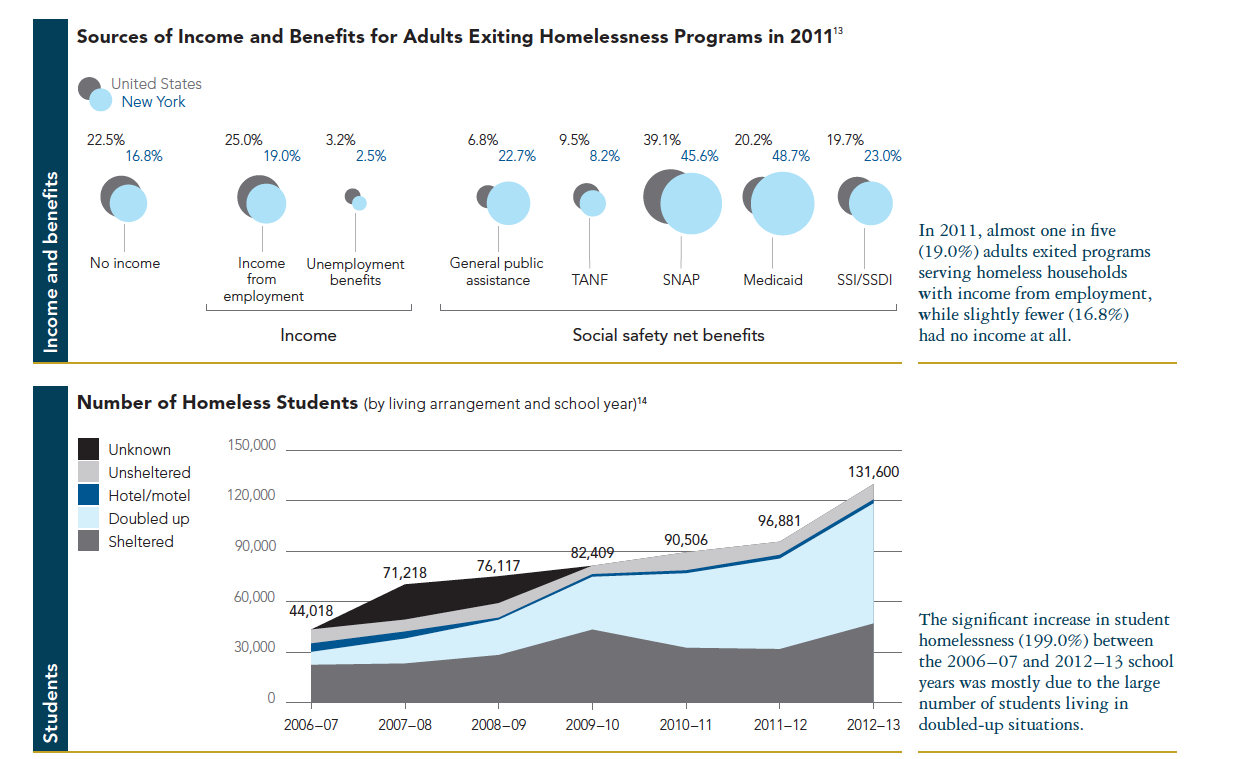

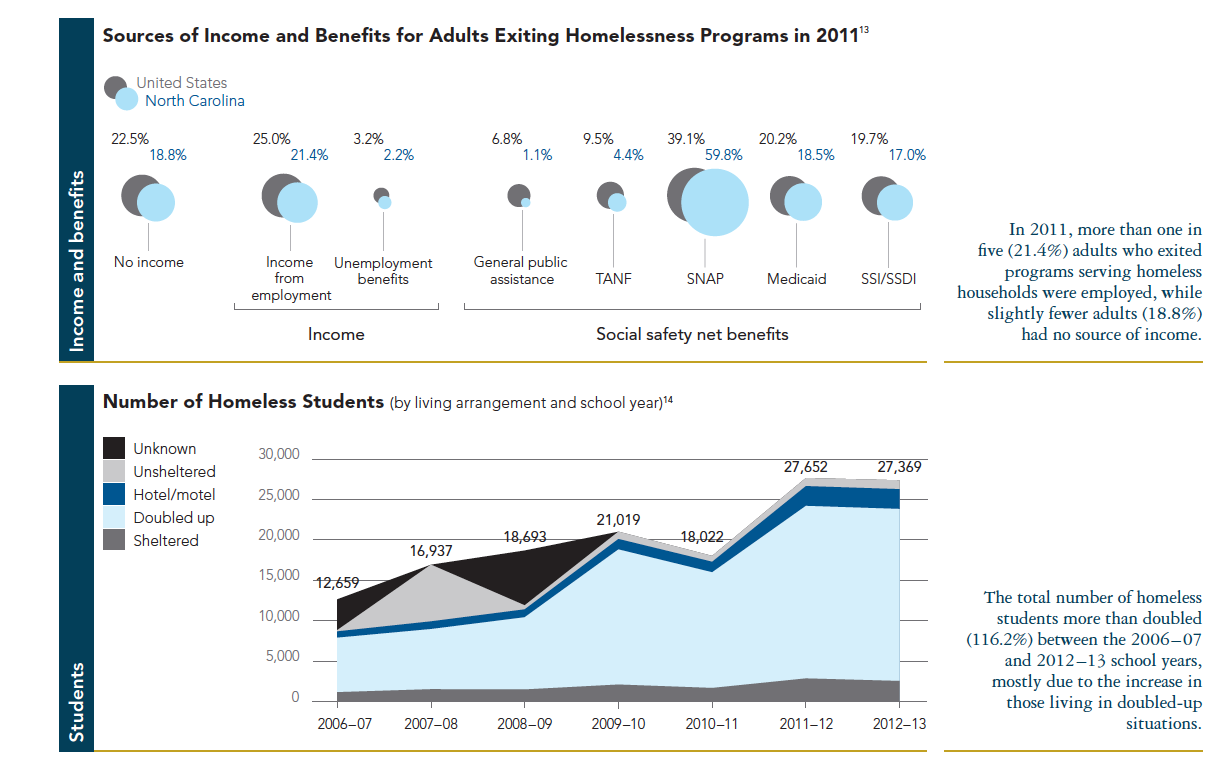

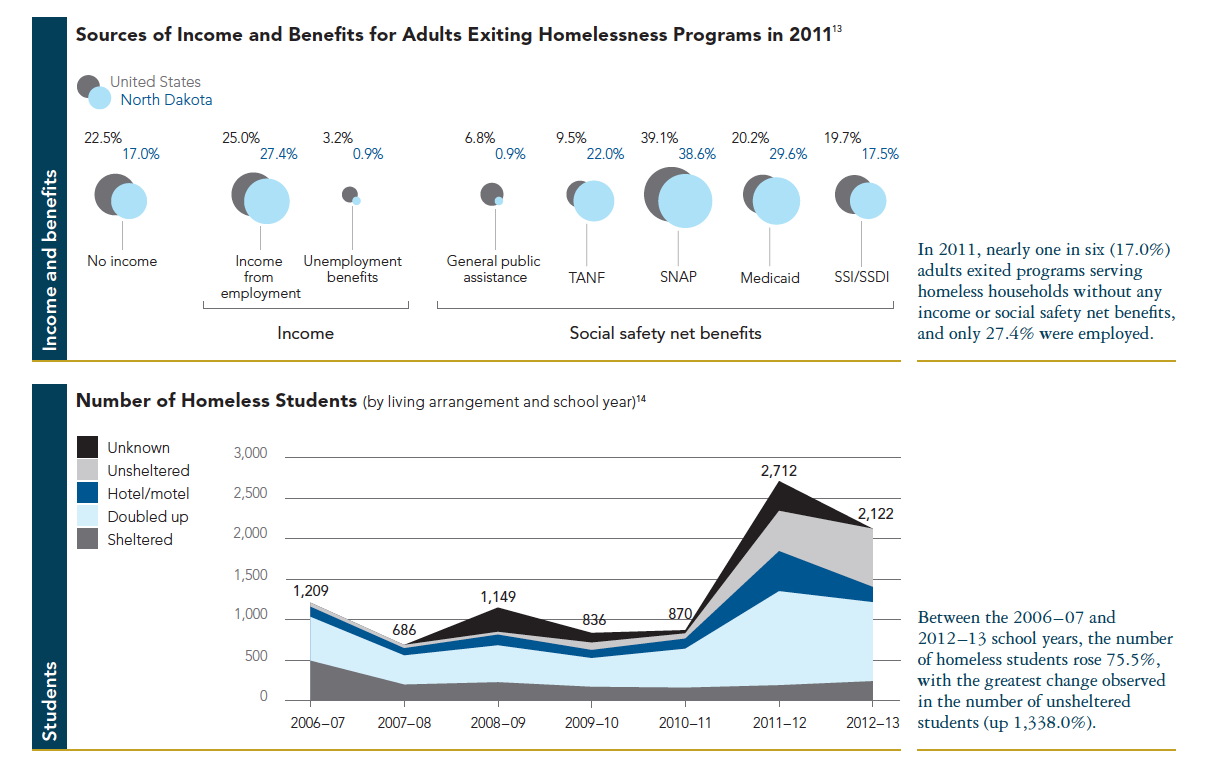

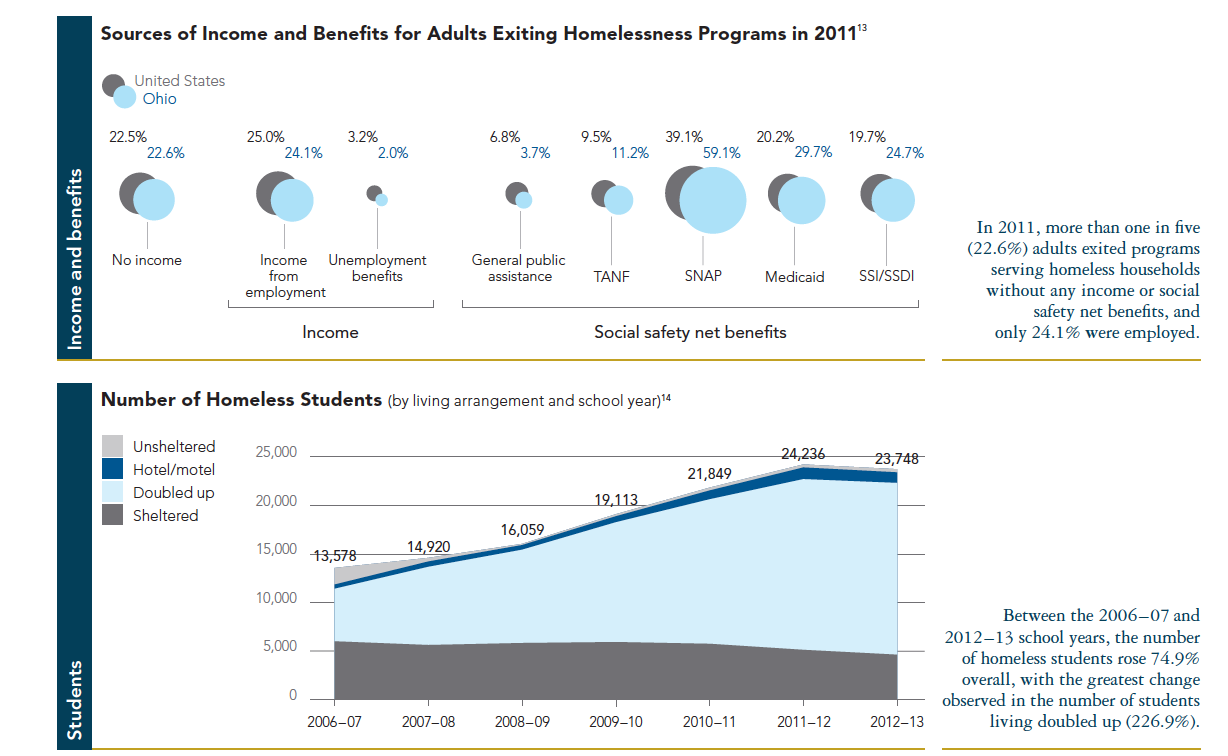

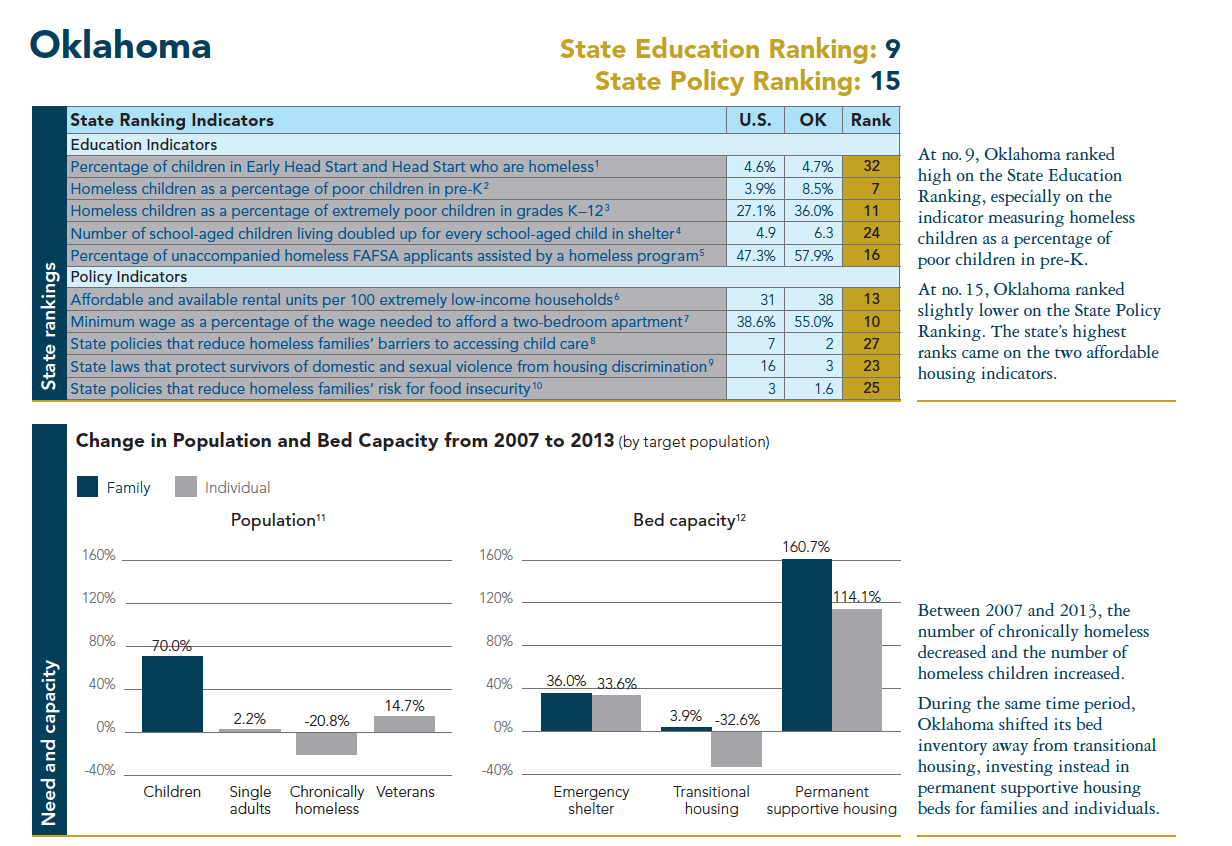

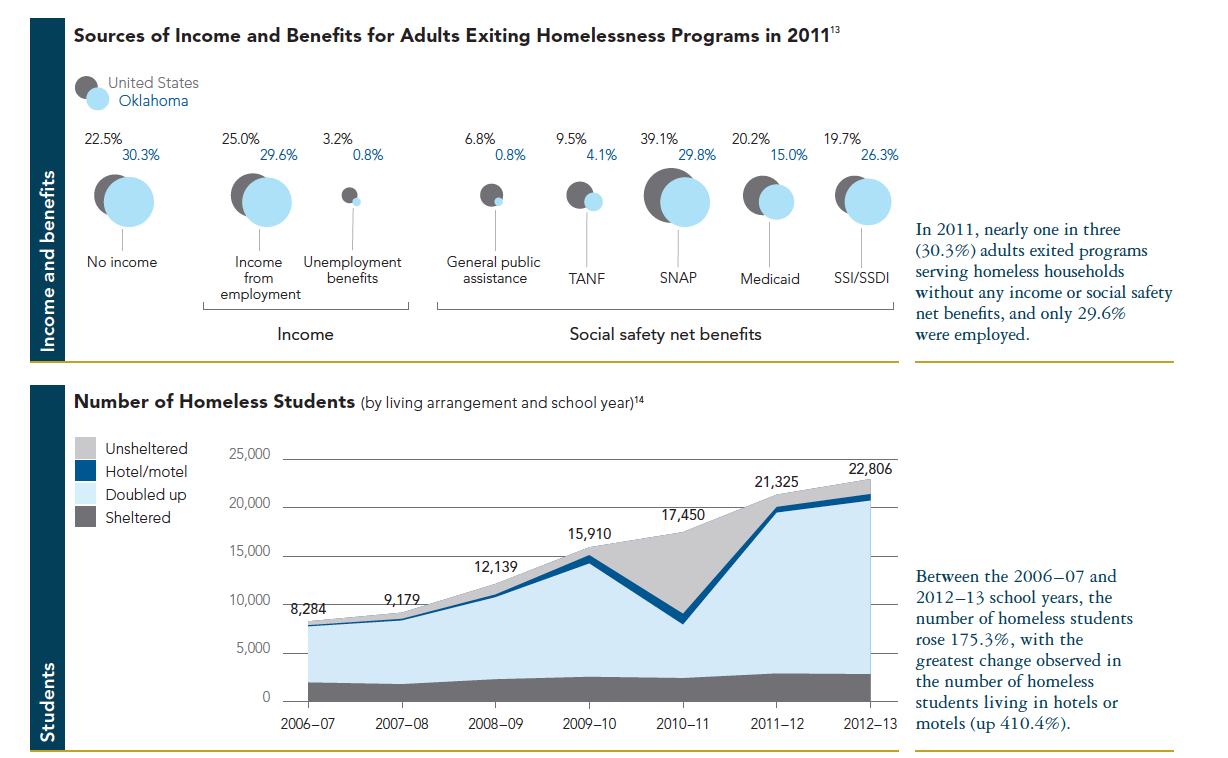

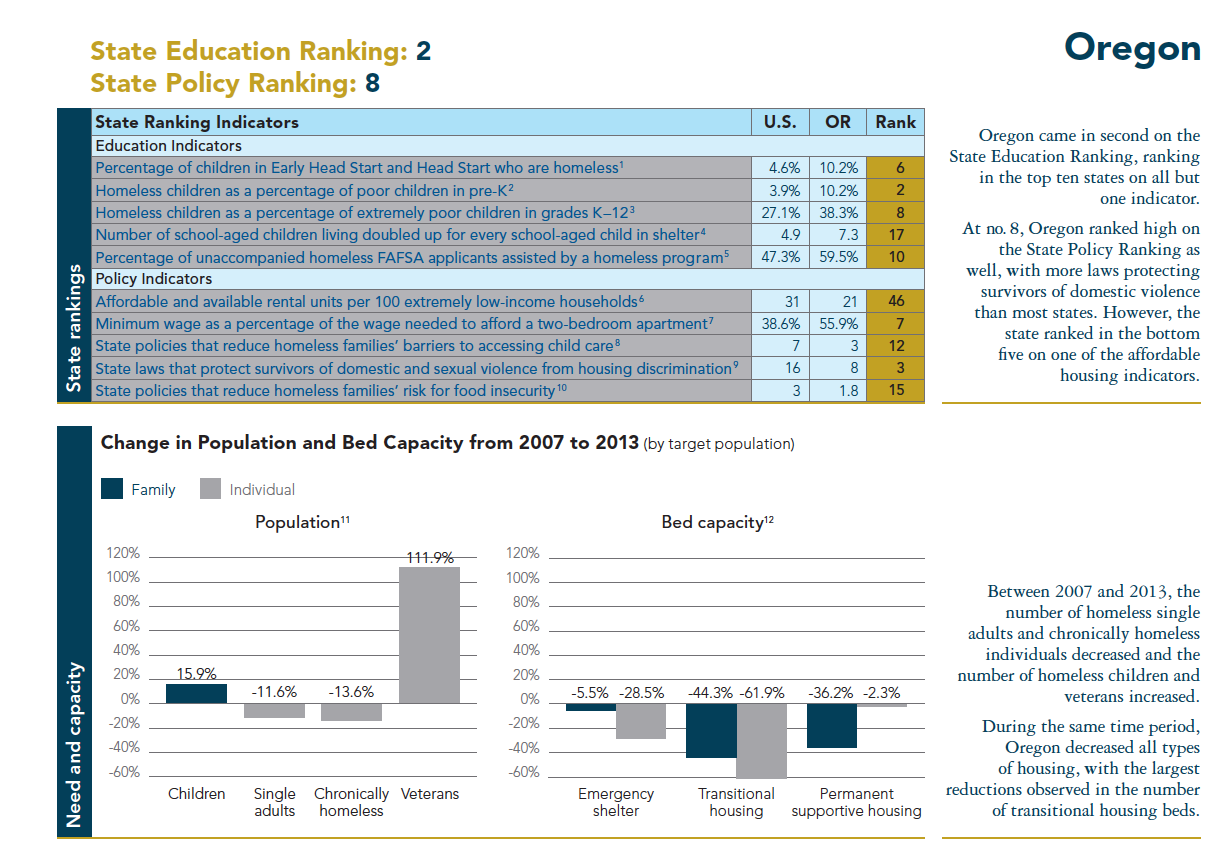

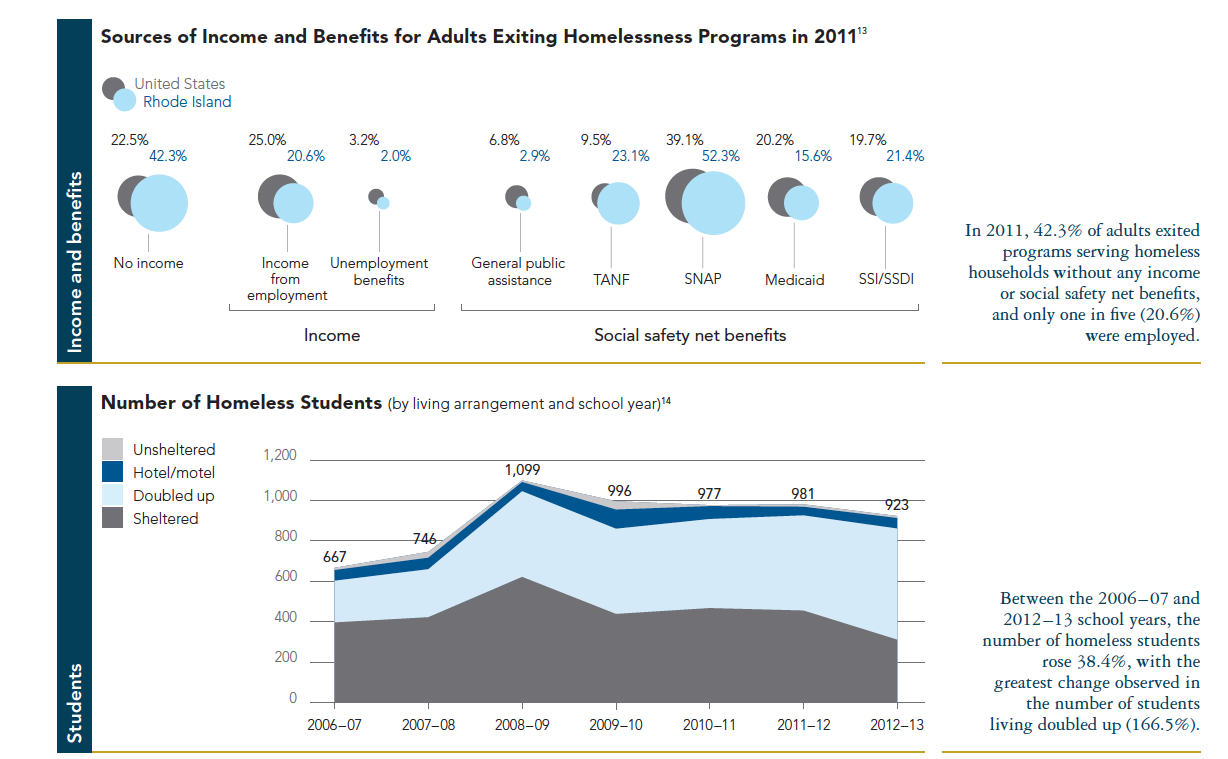

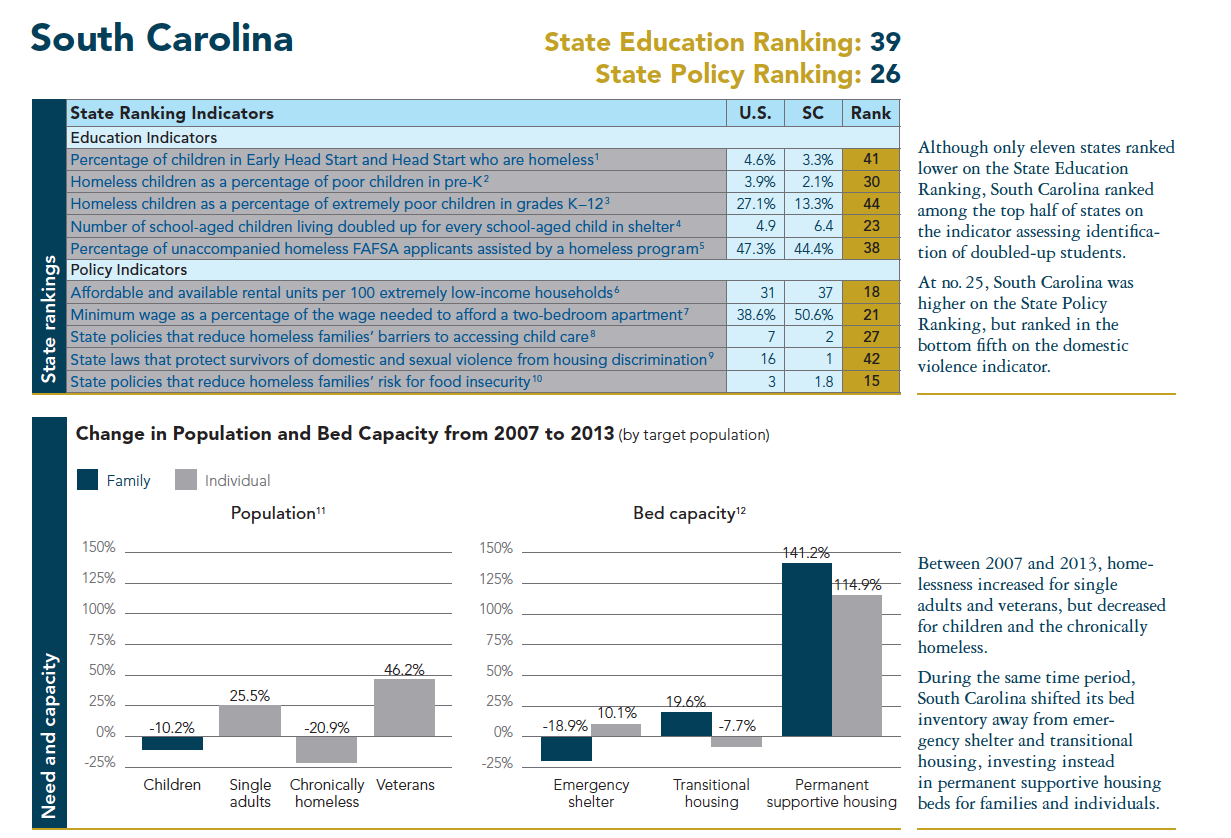

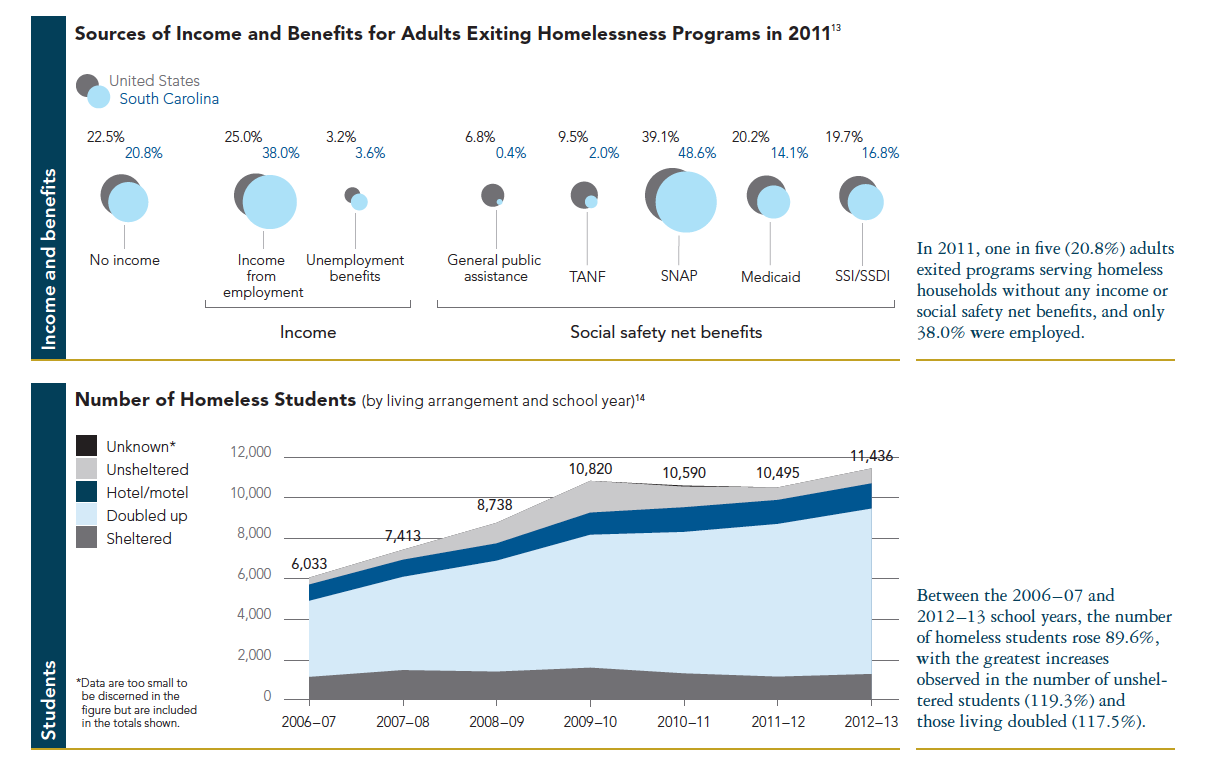

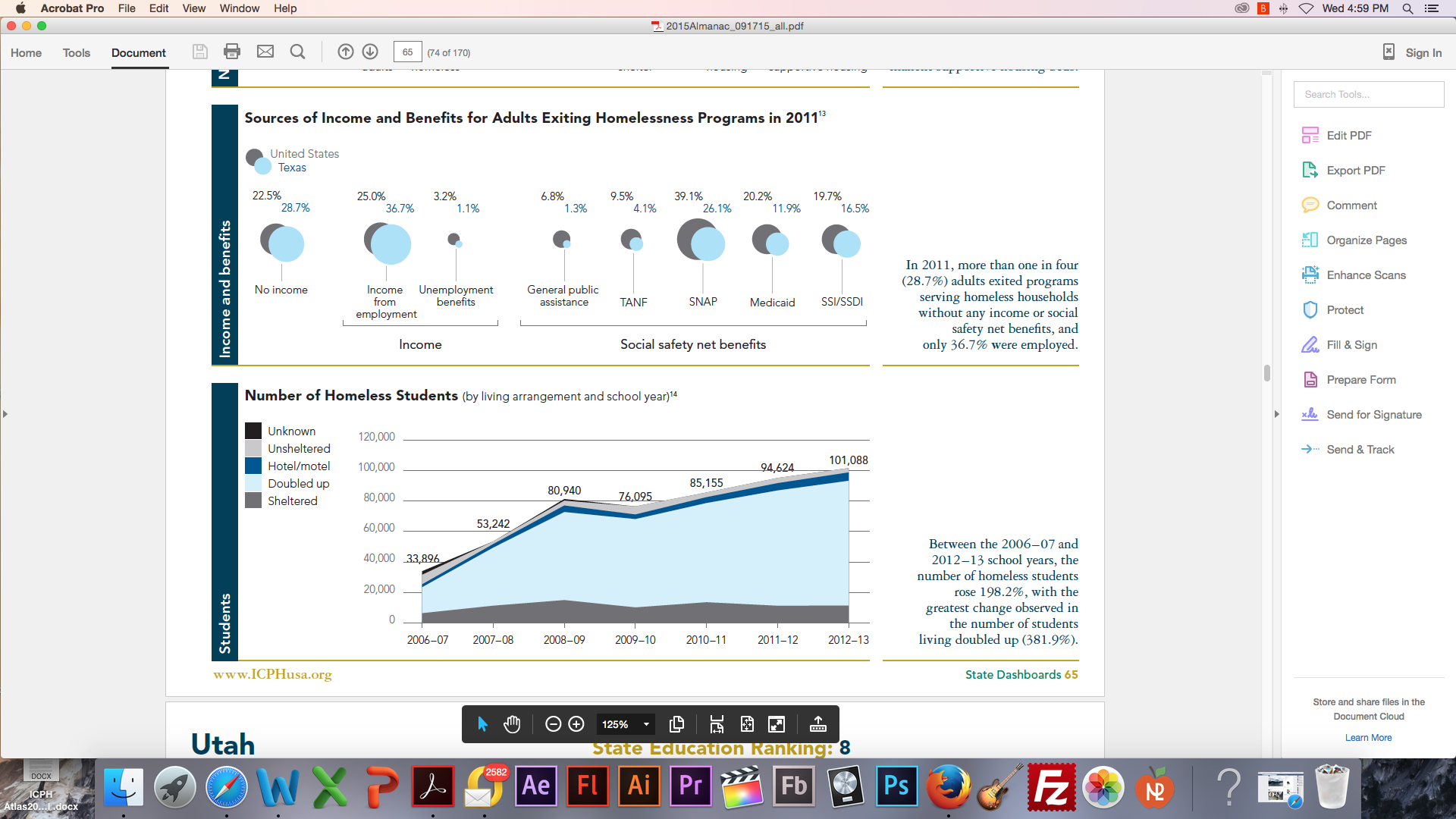

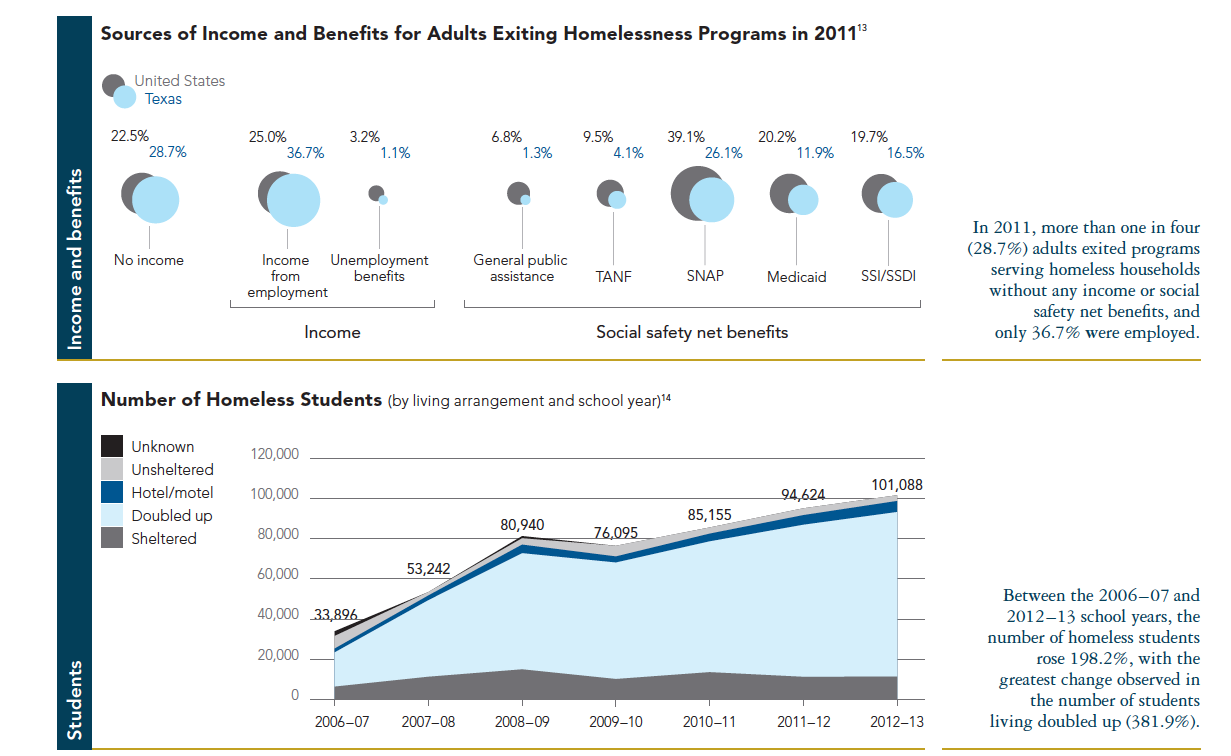

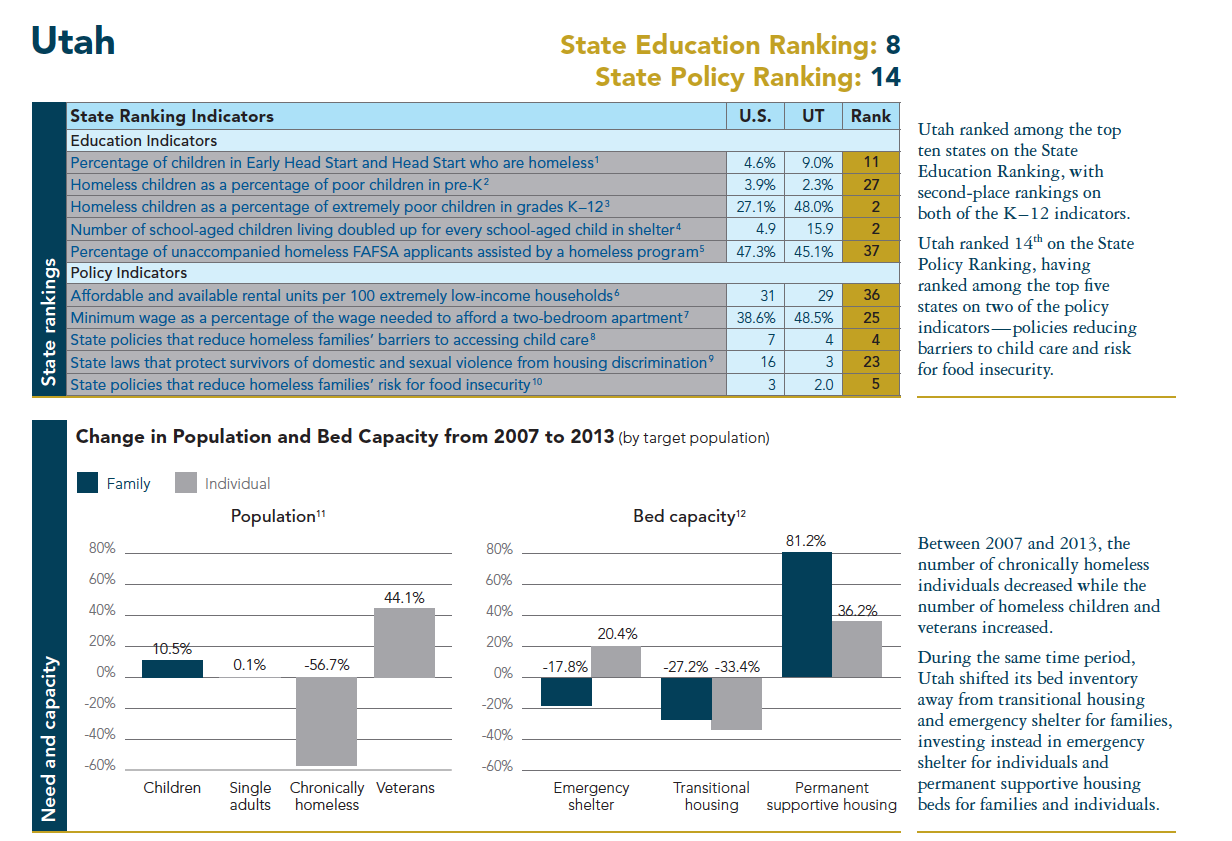

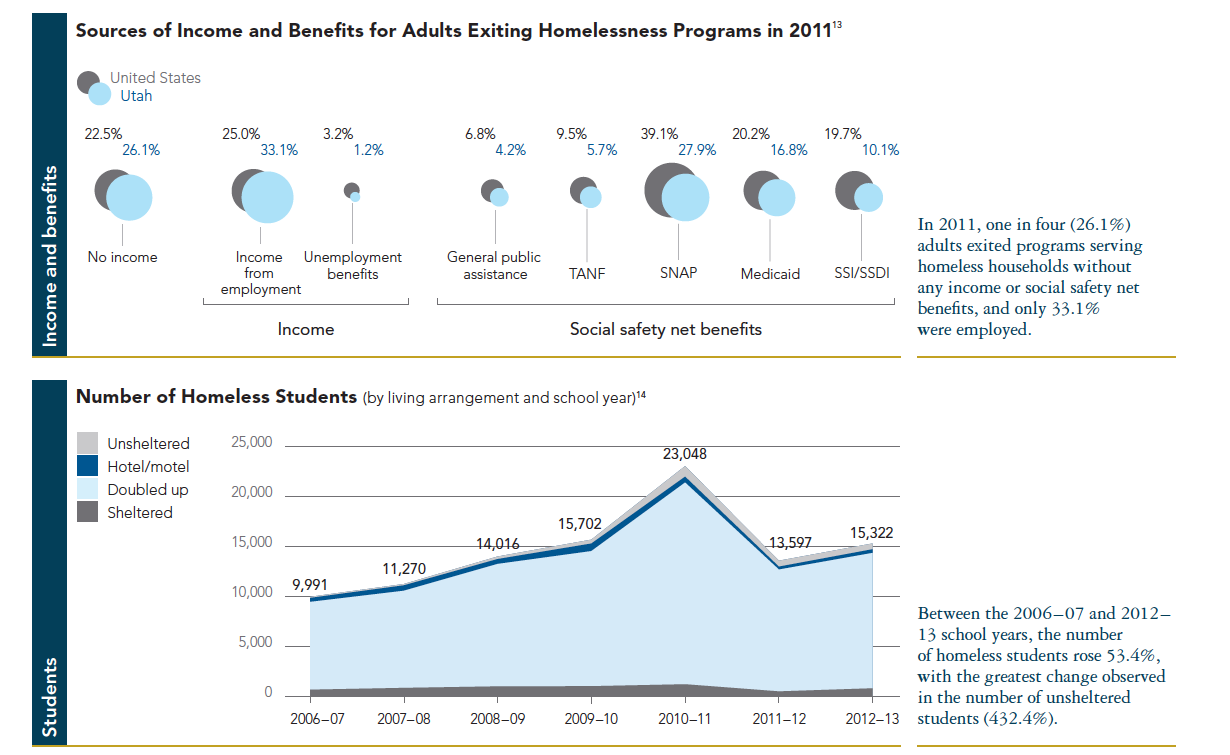

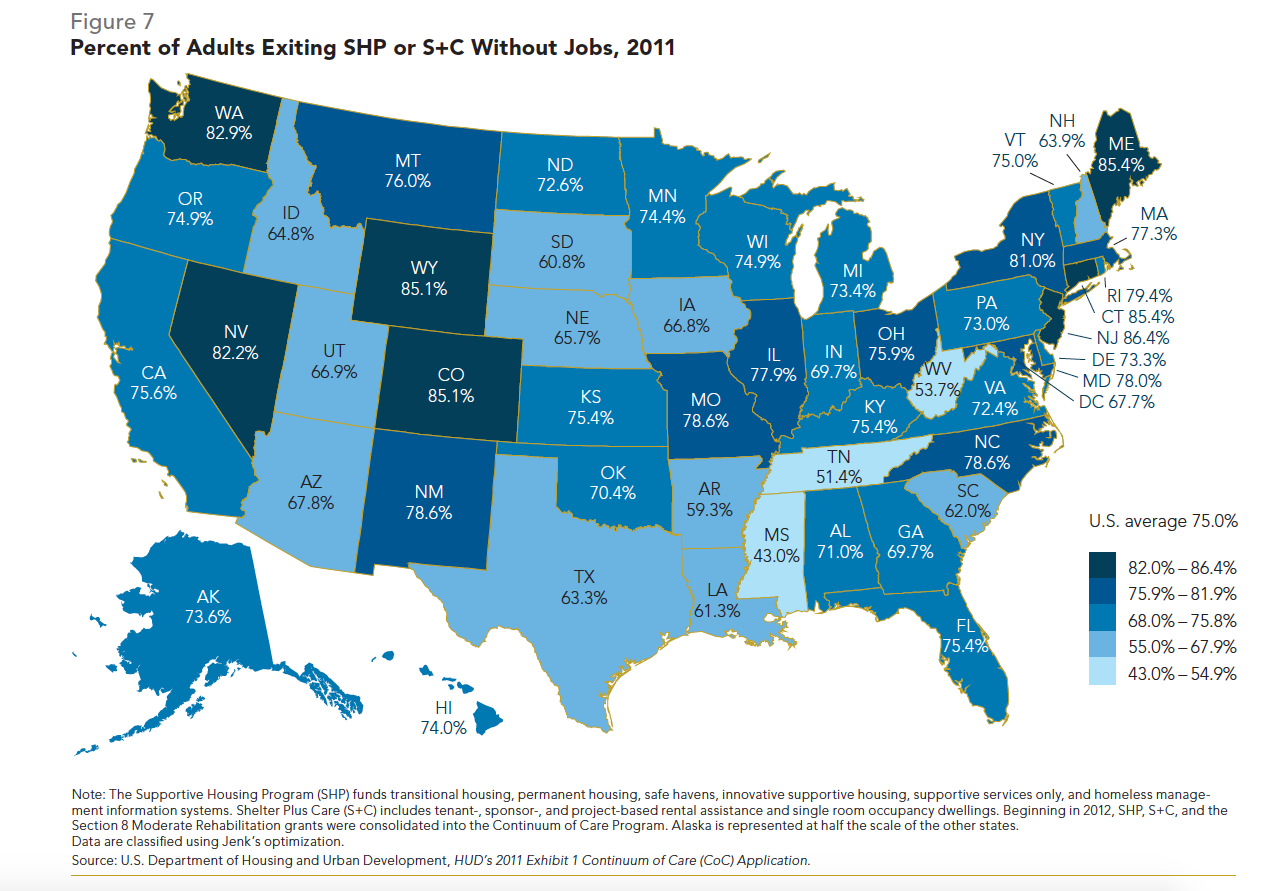

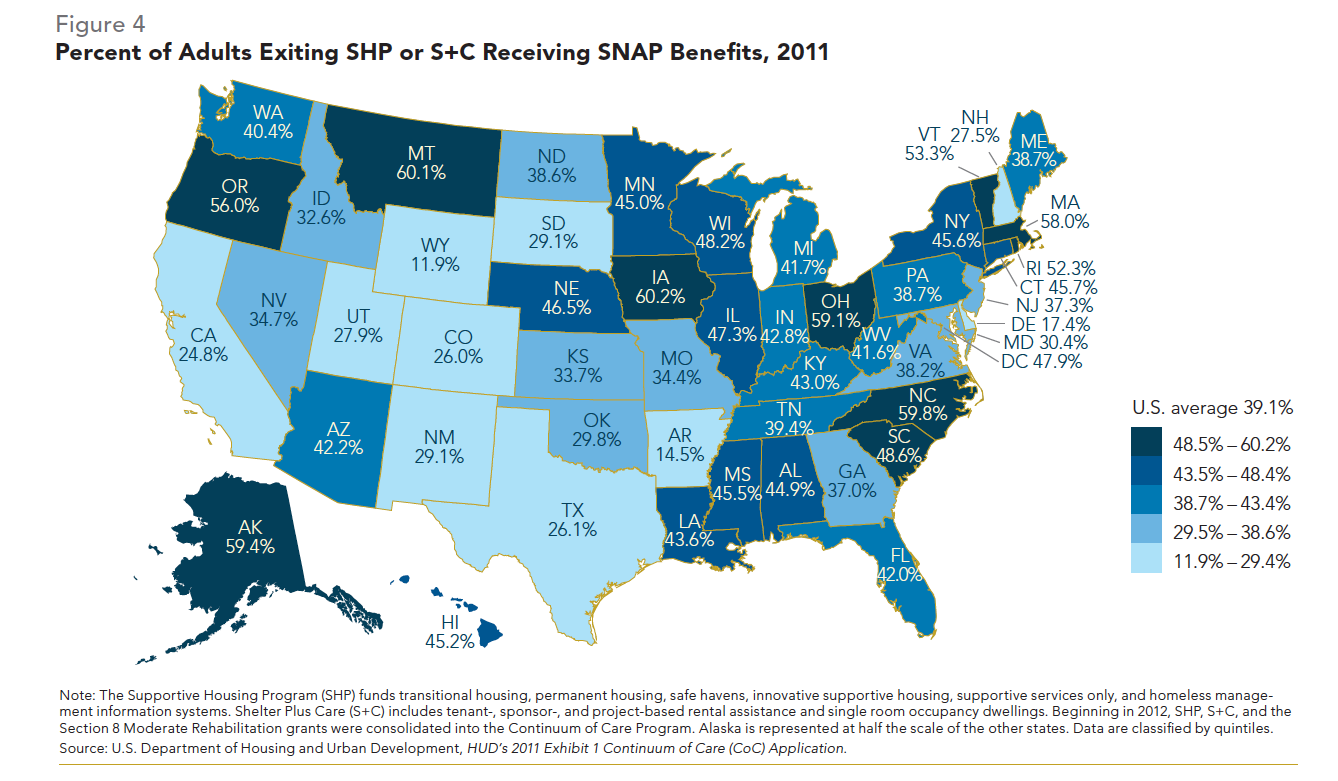

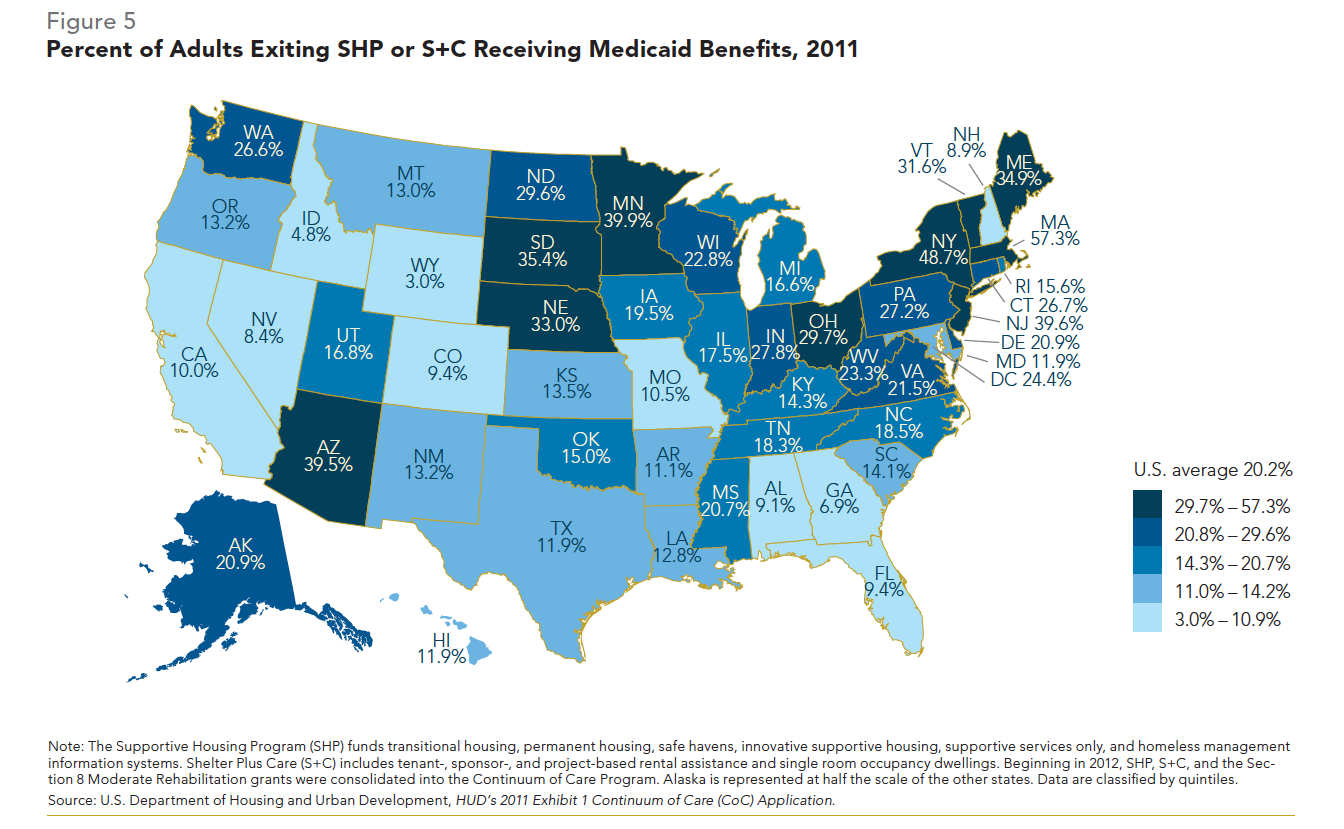

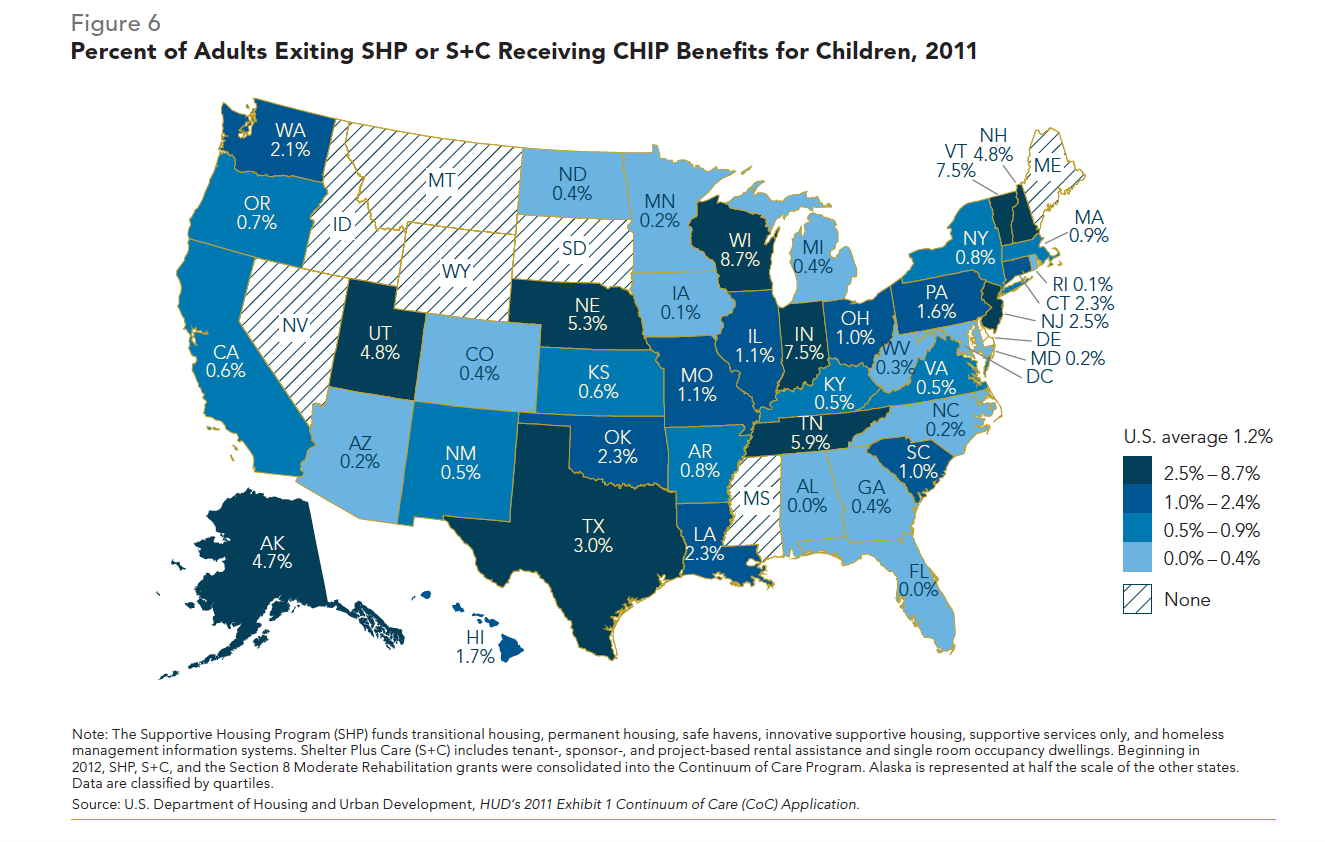

13 Data refers to all adults exiting the Supportive Housing Program (SHP) and Shelter Plus Care (S+C) in 2011. SHP funds transitional housing, permanent housing, safe havens, innovative supportive housing, supportive services only, and homeless management information systems. S+C includes tenant-, sponsor-, and project-based rental assistance and single room occupancy dwellings. Beginning in 2012, SHP, S+C, and the Section 8 Moderate Rehabilitation grants were consolidated into the Continuum of Care Program; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, HUD’s 2011 Exhibit 1 Continuum of Care (CoC) Application.

14 National Center for Homeless Education, Education for Homeless Children and Youth Program Data Collection Summary, 2010–13; U.S. Department of Education, “ED Data Express,” http://www.eddataexpress.ed.gov.

Ideas for Action at a Glance

Education for Homeless Children

- Prioritize access and increase outreach to expand the high-quality early learning opportunities available to young homeless children.

- Increase federal funding for the Education for Homeless Children and Youth program to better serve school-aged homeless children and strengthen policies that support homeless students through the Elementary and Secondary Education Act reauthorization.

- Pass legislation to reduce barriers to receiving financial aid and improve services for homeless students attending college.

For more information see Issues 4 and 6 and the State Family Homelessness Rankings.

Policies that Support Homeless Families

- Pass legislation to increase federal funding for the National Housing Trust Fund to expand the supply of affordable housing.

- Increase federal funding for child care assistance and implement homelessness-specific policies to facilitate families’ access across all states.

- Enact state laws to protect survivors of domestic and sexual violence from housing discrimination and increase federal funding for domestic violence shelters.

- Adopt state-level Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) and Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) policies that reduce homeless families’ risk for food insecurity.

For more information see Issues 2, 3, and 6 and the State Family Homelessness Rankings.

Research and Targeted Assistance - Collect and publicly release national data through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) that is necessary to prevent and reduce family homelessness.

- Expand HUD’s definition of homelessness to include families living doubled up to align with the definition used by other federal agencies.

- Dedicate federal funding exclusively for homeless children and their families, consistent with efforts for chronically homeless adults and veterans.

For more information see Issues 1, 2, 3, and 5 and the State Family Homelessness Rankings.

Ideas for Action

Federal- and State-level Policy Recommendations to Address Family Homelessness

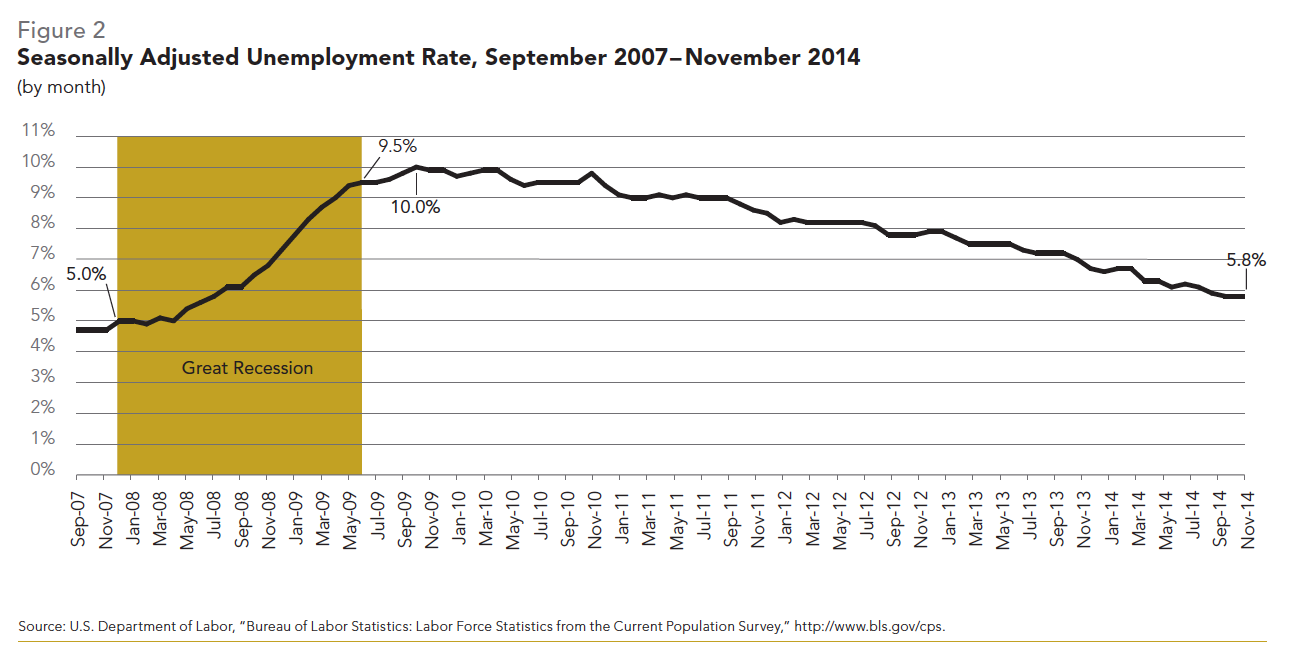

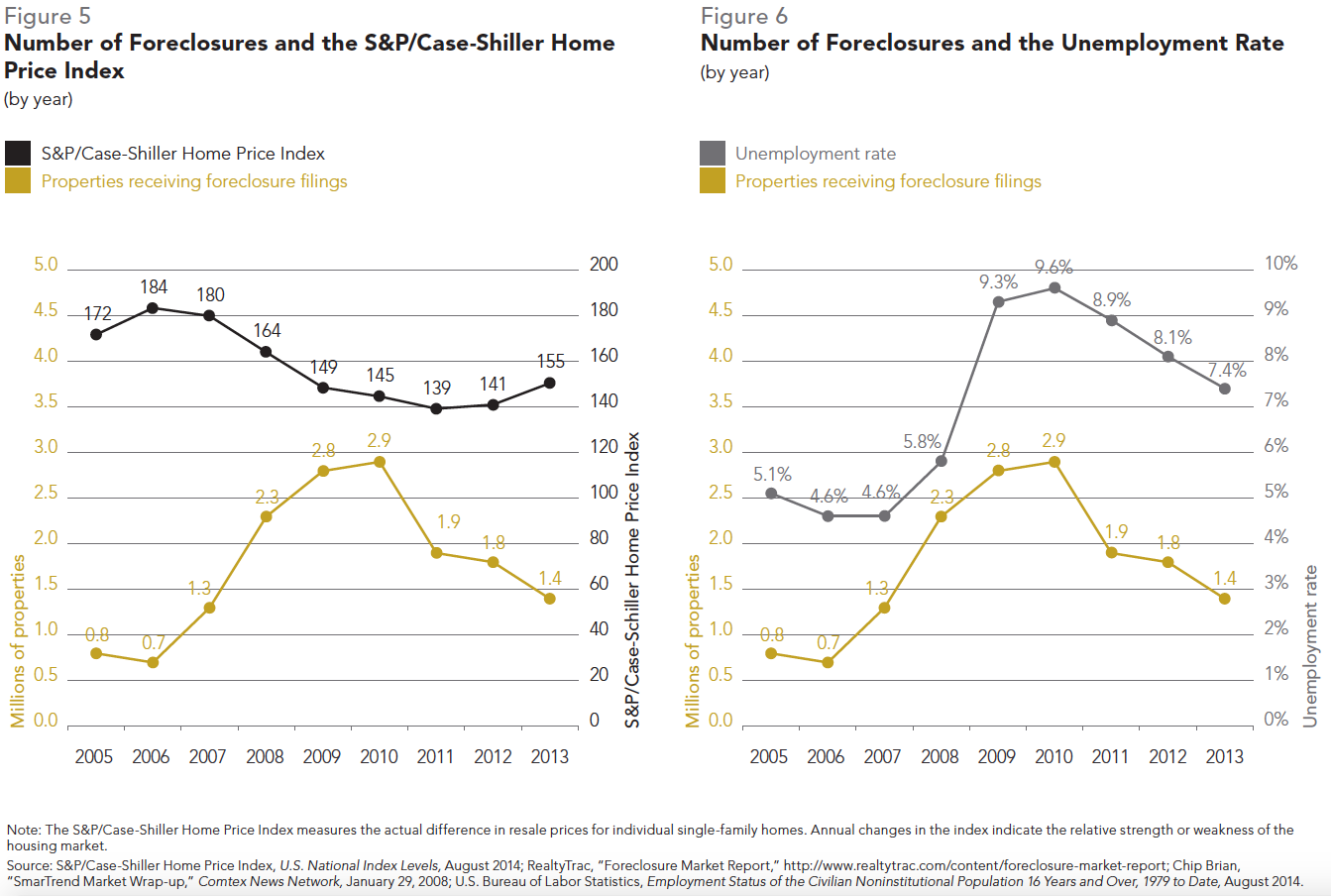

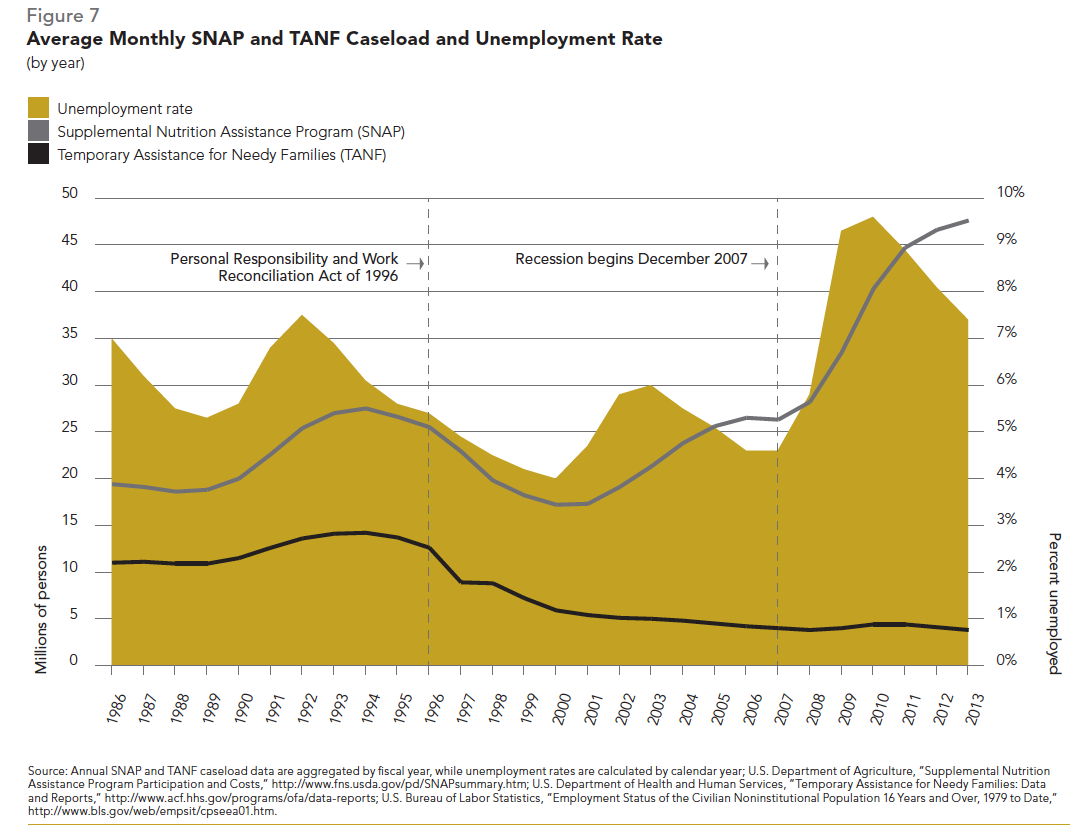

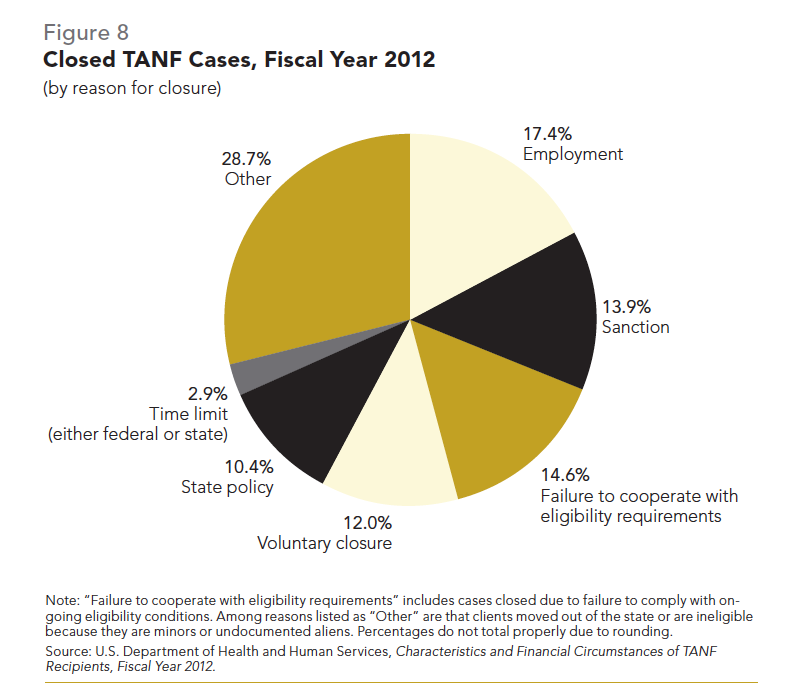

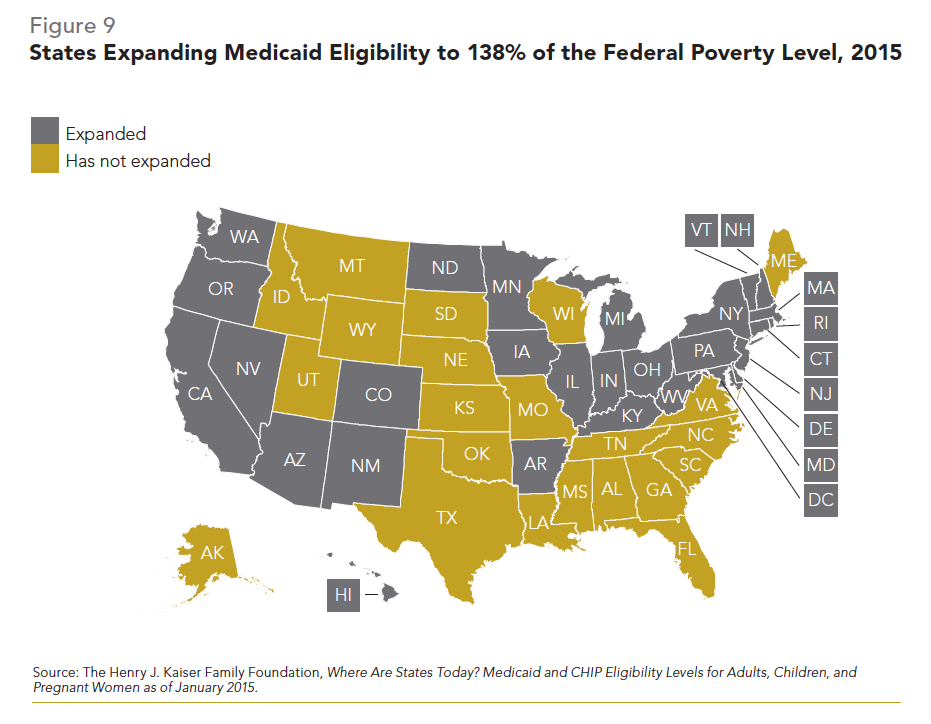

The forces that drive families from their homes are multi-faceted and interdependent, ranging from factors like housing costs and low wages to domestic violence and poor health. Yet federal, state, and local policy choices matter to homeless families as well, often meaning the difference between families at risk of homelessness remaining in their homes or losing that stability. The Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness’ (ICPH) policy recommendations outline a number of practical and cost-effective strategies to better meet the needs of homeless children and their parents.