Publisher’s Note

Dear Reader,

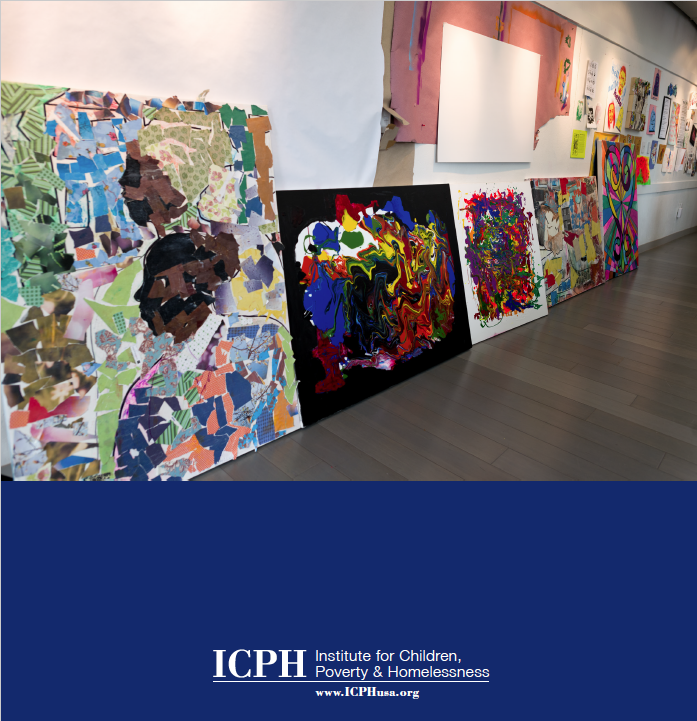

Every two years, the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness hosts “Beyond Housing: A National Conversation on Child Homelessness and Poverty” in New York City. Our 2016 conference brought together over 600 service providers, policymakers, researchers, and practitioners from across the country and around the world to discuss best practices and share insights on how to address the issue of family homelessness with tools that stem far beyond simply housing.

One of UNCENSORED’s central goals is to promote innovative approaches that go beyond housing to support children and families experiencing homelessness. We have dedicated our Spring 2016 issue to the 2016 Beyond Housing conference, spotlighting the ideas shared, the conversations sparked, and the organizations and individuals honored with the Beyond Housing award for their work providing services and support to homeless families while keeping the needs of children at the forefront.

“Home Is Where the Art Is” takes an in-depth look at one of our 2016 Beyond Housing award winners, Washington, DC’s Project Create, and how therapeutic arts programming builds resiliency in more than 500 children and youth experiencing homelessness and poverty. “CATCHing Signs of Trauma” examines the creation, implementation, and impact of another Beyond Housing award winner, Project CATCH, a program of the Wake County, North Carolina Salvation Army which ensures children experiencing homelessness have access to services that nurture their health and well-being. In “Diana Bowman: A Conversation on Student Homelessness,” we talk with our third award winner, Diana Bowman of the National Center for Homeless Education at SERVE, who spent her career working on behalf of homeless students and their families.

Throughout this issue, we represent many of the inventive programs and models presented in the Beyond Housing conference breakout sessions. One of these, a parenting education program, and its application to families in shelter, is profiled in “SafeCare.” As always, we welcome your comments and ideas for future stories at info@ICPHusa.org.

Sincerely,

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, Publisher

President and CEO, Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

Download this article here.

Beyond Housing—

A National Conversation on Child Homelessness and Poverty 2016

From January 13–15, 2016, ICPH hosted the 4th biennial Beyond Housing conference, bringing together more than 600 people from 42 states and six countries in New York City to discuss best practices and share insights on how to address the issue of family homelessness with tools that stem far beyond simply housing.

Pre-Conference Site Visits

The first day of the conference brought participants to one of five different sites in New York City and the surrounding area that provide direct service or opportunities to homeless, formerly homeless, or at-risk youth, children, and families.

One group travelled to the Ali Forney Drop-In Center in Harlem, the nation’s first 24-hour drop-in center for homeless LGBTQ youth. Here, youth ages 16 to 24 receive access to food, medical care, mental health services, education, and job training.

The center recently launched a housing program for the specialized needs of homeless transgender teens and offers hormone therapy at a medical clinic. Those who visited the Ali Forney Drop-In Center learned about the safe and supportive environment the center provides to this vulnerable and often underserved population.

The New York City Family Justice Center, Manhattan, provides free criminal justice, civil, legal, and social services for survivors of domestic violence, elder abuse, and sex trafficking. Participants who attended this site learned how 21 key city agencies, community, social, and civil legal services providers, and the district attorney’s office located on-site work together to make it easier for survivors to get help. Children and parents are served regardless of immigration status, income, or language spoken, and a children’s room gives kids a place to play while their parents receive services.

Another group of participants toured Broadway Housing Communities’ Sugar Hill Development. This affordable housing site is also home to an early childhood center for more than 100 children and a museum of children’s art and storytelling. The museum, which is focused on the developmental needs of children ages three to eight, maintains art exhibits, hosts an artist-in-residence, and employs a number of storytellers. The Sugar Hill Development meets the needs of the community with their emphasis on child- and family-centered programming.

For those who traveled to Yonkers, New York, Greyston Bakery described their open hiring policy. The bakery employs people regardless of their level of education, work history, or past social barriers, such as incarceration, homelessness, or drug use. Greyston also provides support, resources, and other social services that offer a road map to self-sufficiency in a program they refer to as “pathmaking.” Greyston Bakery was featured in our Spring 2014 issue of UNCENSORED magazine.

“It’s always informative to see something firsthand. I have read about Greyston but took away so much more as a result of this visit,” commented one attendee.

The fifth group of site visit attendees toured Saratoga Family Inn, a Community Residential Resource Center (CRRC) operated by Homes for the Homeless. CRRCs combine the basic services of a traditional shelter with a wide variety of programs for families residing in the shelter and those from surrounding neighborhoods. The Saratoga offers child-centered services such as day care, after-school, and recreation programs, in addition to adult services like career training, housing assistance, and life-skills classes.

Site visit attendees commented on how helpful it was to see how other programs similar to their own operate, to learn the challenges they have faced, and to hear the lessons they have to share.

Beyond Housing—Day One

Welcome, Letitia James

The conference proper kicked off with welcoming remarks from New York City Public Advocate Letitia James. Public Advocate James helps to make the voices of those facing discrimination and injustice, and those without resources, heard in government. She has a long history of advocating for children and families through her work for universal free lunch in public schools, protecting children in foster care, advocating for family leave, and fighting to raise the minimum wage. She has worked to put a face on what homelessness is, not just in New York City, but also around the country.

New York City Public Advocate Letitia James examined the realities facing the 77,000 homeless students in New York City.

In her remarks, the Public Advocate emphasized that homelessness is multifaceted—and it is a children’s issue. “There are too many children in our homeless system. Homeless children are the most vulnerable New Yorkers. They are voiceless, and invisible.”

Public Advocate James went into depth about the student homelessness crisis New York City now faces, explaining that there are 77,000 homeless students in New York City’s public school system. “Some of these children are in shelters, some are sleeping on couches at friends’ houses or relatives apartments. The impact of having an unstable home environment is traumatic on children; it has a lifelong impact.”

“There are too many children in our homeless system. Homeless children are the most vulnerable New Yorkers. They are voiceless, and invisible.”

—Letitia James

“Children are our most precious resource,” she continued, “and these are the most formative years of their lives. We need to do more to ensure they have a stable home, food to eat, and have the energy to come to school every day and learn. We know that education is the key to ending poverty.”

She also spoke about the realities of family homelessness in New York City, the challenges these families face, and the factors that contribute to their homelessness. According to Public Advocate James, there are gaps in the services available for these families and systematic changes need to be made. “We need more resources for our most vulnerable, our defenseless, and our innocent children.”

Remarks, Dr. Ralph da Costa Nunez

Following the Public Advocate’s inspirational remarks, Dr. Ralph da Costa Nunez, president of the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness detailed how the country arrived at the family homelessness crisis it faces today. Dr. Nunez argued that after 30 years, this issue should no longer be called a homelessness “crisis,” but rather an institutional problem of very severe poverty.

“For 30 years we have been approaching homelessness in the wrong way. We have been trying to make families fit into shelters and fit into policy systems that we have put in place— when we should be making shelters fit families. What are their needs?”

—Dr. Ralph da Costa Nunez

In New York, and across much of the country, the policies to reduce homelessness have included housing, prevention, and vouchers. However, as Dr. Nunez noted, each of these policies has limitations. In addition, there are different types of homeless families with varying levels of need. There is no one-size-fits-all policy. One priority for addressing family homelessness, however, is education. Dr. Nunez argued that if we fail to address the educational needs of homeless children, the cycle of poverty will continue. To meet these educational needs, services must be provided in shelter. “For 30 years we have been approaching homelessness in the wrong way. We have been trying to make families fit into shelters and fit into policy systems that we have put in place—when we should be making shelters fit families. What are their needs?”

Keynote, Richard Rothstein

For the morning keynote, Richard Rothstein, a research associate focusing on education, race, and ethnicity from the Economic Policy Institute, took a step back to put the country’s current economic and social crises in a broader context by looking at how the U.S. arrived at the segregation and racial inequality it faces today.

Richard Rothstein argued that the segregation cities and schools face today is not by accident, but rather a direct result of public policies.

Mr. Rothstein, former national education columnist for the New York Times, former visiting professor at Teachers College, Columbia University, and author of Class and Schools: Using Social, Economic, and Educational Reform to Close the Black-White Achievement Gap, spoke about the failure of the social and economic conditions that bring children to schools with concentrated disadvantages. When every child in a school has disadvantages, Mr. Rothstein said, teachers cannot dedicate the time and resources they need to each and every one of them. These are not failing schools; it is a failing social system. “We will never accomplish the things we want to accomplish in our schools so long as our schools are segregated. And schools are increasingly segregated in this country today. They are more segregated than at any time since Brown v. Board of Education.”

“Public policies have segregated every metropolitan area in the country in violation of constitutional provisions.”

—Richard Rothstein

Mr. Rothstein argued that this segregation is not by accident, but rather it is segregation by public policy. He cited the long history of government policies (such as public housing laws, racial zoning ordinances, homeownership laws, and the redlining of neighborhoods) that led the country to this point. According to Mr. Rothstein, “Public policies have segregated every metropolitan area in the country in violation of constitutional provisions, imposing upon us an obligation which we have not recognized, and which if we do not recognize will continue to leave us in the situation we are in.”

“So long as we think segregation happened by accident,” he continued, “it is inevitable that we would think it can only be corrected by accident. If we understand, however, that this is a state system of segregation whose effects endure to this day, all kinds of possibilities open up to address it.”

Lunch Keynote, Peter Miller

The lunch keynote was given by Peter Miller, associate professor at the School of Education and Institute for Research on Poverty at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Mr. Miller was formerly a high school teacher and shelter employee and now studies issues of leadership, policy, homelessness, poverty, and university-school-community partnerships.

Peter Miller’s keynote focused on everyday innovations that anyone can use to make a difference in the lives of children experiencing homelessness.

Mr. Miller shared the lessons he learned from the last 10 years in shelters, schools, and early childhood centers, stating, “If we want to learn about and respond to homelessness, we cannot do it from a comfortable distance.”

His keynote speech focused on every day innovations that can be made by anyone to support homeless children and their families. Mr. Miller recognized that in the field of family homelessness there are big policy solutions, small day-to-day service questions, and the work “somewhere in the middle.” He suggested numerous ways that individuals working “in the middle” can function best, to shape the everyday in a positive way.

“If we want to learn about and respond to homelessness, we cannot do it from a comfortable distance.”

—Peter Miller

He recommended refocusing on making the everyday better. According to Mr. Miller, the everyday “is not inconsequential.”

To best serve homeless children and families, Mr. Miller suggested using the acronym BEETZ:

- Brokering—connecting with people where they are.

- Embedding—staying connected and getting up close to the issue to reduce gaps in perception.

- Experimenting—allowing new ideas to come forward and trying new things.

- Targeting of high doses—focusing on and making use of the everyday, routine activities.

- Zeal in all practice—working with enthusiasm and passion.

Reception and Awards

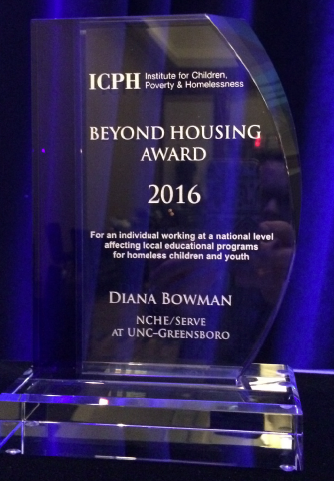

Day One ended with a reception and awards ceremony hosted by ICPH. The Beyond Housing award honors people and organizations whose work exemplifies the idea that homelessness is much more than a housing issue. Recipients’ work goes “beyond housing” to provide services and support to homeless families while keeping the needs of children at the forefront.

Project Create in Washington, DC received the Beyond Housing award for an organization working locally with children in shelter and in the community to nourish their minds, creativity, and curiosity. Maggie Ridden, executive director of the DC Alliance of Youth Advocates, who nominated Project Create for the Beyond Housing award, explained, “Project Create provides thousands of local DC students living in homelessness, who are unstably housed or in high-poverty neighborhoods, with the opportunity to transform their lives through artistic expression. It is a profound thing to give a young person when everything else is unstable.”

“I spend a lot of time navigating the homeless world,” she continued. “What I have discovered is that rarely is a space youth friendly. A space that empowers young people to be creative, to have their own opportunities for discussion and creative thought, and to self explore. Those are all elements that go beyond housing to make an enriching, holistic youth development process, opportunity, and program, which is why we ultimately nominated Project Create for this award.”

Upon receipt of the award, Project Create Executive Director Christie Walser noted, “The act of artistic creation is transformative and all children have the right to experience the arts.” Project CATCH received the Beyond Housing award for an organization working comprehensively to address the needs of homeless families. Mary Haskett, a professor at North Carolina State University and advisory board member of Project CATCH, introduced the organization. “CATCH stands for Community Action Targeting Children Who Are Homeless and it is a community collaboration of 11 programs in the Wake County, North Carolina area that serve families experiencing homelessness. The focus of the project is really to be the voice of children’s mental health.”

Jennifer Tisdale, coordinator of Project CATCH, accepted the award and explained, “We are all about people; we are about connection, we are about relationships, and more than anything we are about the kids.”

A third award, for an individual working at a national level affecting local educational programs for homeless children and youth, was given to Diana Bowman, former director of the National Center for Homeless Education at SERVE.

“For over 20 years, the work that I have done on behalf of homeless children and youth has been a passion, a mission, and a labor of love,” she said in a video accepting the award. “I think it is all of us working together that are able to make a difference for these homeless children and youth.”

Their work is featured in this issue of UNCENSORED.

Beyond Housing—Day Two

The second day of the conference began with a presentation by Nisha Beharie, postdoctoral fellow at the National Development and Research Institutes, and Angela Paulino, project coordinator at the McSilver Institute for Poverty Policy and Research at New York University, on the HOPE Family Program (HIV Prevention for Parents and Early Adolescents). Ms. Beharie and Ms. Paulino spoke about the development and implementation of this family-based, HIV and substance use prevention education program for homeless youth living in New York City Tier II shelters, as well as the findings from a study on the effectiveness of the program.

Final Keynote, Linda Tirado

The final keynote was delivered by Linda Tirado, author of Hand to Mouth: Living in Bootstrap America. In her book, and at the conference, Ms. Tirado told her own story of poverty, housing instability, and raising a family on minimum and low-wage jobs while placing her story in the greater context of what it means to be poor in America today.

Linda Tirado told her story of poverty, housing instability, and raising a family on minimum and low-wage jobs while placing her story in the greater context of what it means to be poor in America.

She explained, “There is a sense of disenfranchisement. That sense that the government is not ‘doing,’ the sense that there is no ‘we’— it is us against them.”

Ms. Tirado brought with her a fresh and candid perspective of the struggle those living in poverty face, addressing the many misconceptions about poverty and homelessness and emphasizing the need for less judgment and more understanding.

“We cannot have an underclass that continues to grow and a country that is going to be stable.”

—Linda Tirado

“The point is, we are all in this together and it is our problem if we do not understand that with a quickness. We cannot have an underclass that continues to grow and a country that is going to be stable.”

She emphasized to those at the conference who work on the front lines of poverty and homelessness the importance of standing by their clients. “It is your job to protect your clients,” she said. “To make a safe space for us to talk about our own trauma without fear that we will be further brutalized.”

Breakout Sessions

Throughout the conference, participants were invited to attend breakout sessions on topics including advocacy and coalition building, employment and adult skill building, education and enrichment, health, organizational and staff development, policy and research, program strategies, shelter and housing, trauma, and youth. More than 50 sessions were offered by organizations from across the U.S. and Canada.

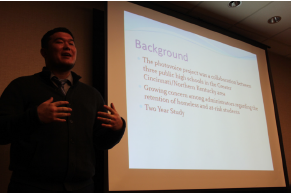

James Canfield from the University of Cincinnati describes a photography project used to give homeless students a voice and to learn more about what they see as their barriers to graduation.

Serving Our Kids Foundation

Dale Darcas, executive director of Serving Our Kids Foundation, presented “How to Build an Effective Coalition to Successfully Serve a Need,” which looked at how his program began by feeding 20 homeless and at-risk children in one school and grew into a coalition that has fed more than 186,000 children.

Serving Our Kids Foundation is an organization dedicated to feeding and serving homeless and at-risk children in Clark County, Nevada. This grassroots, volunteer organization utilizes the strength of community volunteers and donations to ensure children are fed for the weekends and provided with personal care items. As a 100 percent volunteer-based organization, Serving Our Kids Foundation relies on community organizations and volunteers to make its work possible.

Mr. Darcas provided specific suggestions and examples for how best to build a similar coalition:

- Identify a need

- Develop strategic partnerships

- Maintain and grow partnerships

- Build a community of excited volunteers who not only physically turn up to support, but also spread the word to others

- Create positive public awareness

- Connect and build bonds with other community groups

- Empower affluent school children to support children who are just like them, but do not have access to the same resources

- Develop sustainable grassroots fundraising

- Create and execute plans to achieve objectives

Since the Beyond Housing conference, Serving Our Kids Foundation has continued growing. Title I HOPE: Homeless Outreach Program for Education, a program within the Clark County School District, and Three Square, Southern Nevada’s only food bank and the area’s largest hunger-relief organization, have begun working with Serving Our Kids Foundation. In addition, ChildRun chose Serving Our Kids Foundation as one of three charities they will sponsor. ChildRun is an upcoming reality television show that will host a 10K run and dinner gala fundraiser to raise money and awareness for Serving Our Kids Foundation.

“I thank you for inspiring me at your conference to be better and keep going,” said Mr. Darcas when sharing the news with ICPH.

Raising the Roof

Carolann Barr and Caitlin Boros from Raising the Roof, a Canadian organization dedicated to long-term solutions to homelessness, presented “A Holistic Approach to Ending Child and Family Homelessness.” Ms. Barr and Ms. Boros widened the scope with which we look at homelessness by providing a snapshot of the issue in Canada.

More than 235,000 Canadians experience homelessness each year, with young people ages 16–24 making up about 20 percent of the homeless population. Between 2005 and 2009, the estimated number of children using emergency shelter grew by 50 percent. More than 1.3 million children live in poverty in Canada.

Raising the Roof believes that “by educating Canadians, learning from and sharing community-based work, and developing a practical planning framework, we can develop solutions to child and family homelessness in Canada.” As a part of educating Canadians on homelessness, Raising the Roof has generated several public awareness campaigns. The Humans for Humans ad campaign humanizes those experiencing homelessness. In these advertisements, which received international media attention, people experiencing homelessness read mean tweets written about homeless people. Their emotional responses help to dispel some of the misconceptions about homelessness.

According to their report, Beyond Housing First: A Holistic Response to Family Homelessness in Canada, “Homelessness is not a social concern that occurs in a vacuum, but one that intersects with multiple social concerns, including affordable housing, income, food security, discrimination, and gender and intimate partner violence (IPV). When it is viewed this way, solutions can be envisioned in a holistic manner, where interventions are geared at strengthening the foundations of our society, not just ensuring people have housing.”

Photovoice

James Canfield from the University of Cincinnati, and Dana Harley and Amy Trostle from Northern Kentucky University, presented “What Do Homeless Students See as Their Biggest Barriers to Graduation? A Participatory Action Research Project Using Photovoice.”

“This project began when a concerned parent approached our team about the increase in homelessness in her child’s school district,” explained James Canfield, an assistant professor at the University of Cincinnati. “She put us into direct contact with the district’s administration and we began our partnership to combat issues related to dropout [sic] for homeless high school students.”

The group gave each homeless high school student a camera and asked them to take pictures of things that would help them to graduate and things that stood in the way. They then had the students describe what they saw in the photos. Out of these interviews emerged dominant themes of what enabled students to graduate and what barriers to graduation they encountered.

“We presented for school faculty and staff to show what their homeless students faced as they pursued education,” explained Mr. Canfield. “The teachers were literally speechless as we showed them their students’ voices.” The group also held a public gallery show of the photographs.

While many knew the issues that plagued their area, it was powerful for them to see evidence of those issues. For example, heroin is a widely-known problem for the area. “For a student to take a picture of a used needle on their school route deeply impacted school administration and teachers,” said Mr. Canfield.

He concluded, “We provided a voice to homeless students and empowered them to tell the community and stakeholders where change is needed.”

Several other programs from the conference will be featured in future issues of UNCENSORED. Videos of the keynote speeches and the awards reception, and session handouts and PowerPoint presentations, are available at BeyondHousing.ICPHusa.org.

The 2016 ICPH Beyond Housing conference hosted a variety of informative and inspiring keynote speakers, interesting breakout sessions, and interactive site visits for more than 600 attendees.

Download this article here.

Download the Databank here.

Download this article here.

Home Is Where the Art Is: Therapeutic Arts Programs for DC Children and Youth

by Lauren Blundin

Project Create is on a mission: to create art, to create opportunity, and to create community. The nonprofit deploys about 30 professional artists each year to teach art to children and youth in partner sites throughout Washington, DC’s Wards 7 and 8, and also maintains a studio in Ward 8, known as the Anacostia neighborhood of the District of Columbia. The area is challenged by poverty and crime. In fact, in this area it is not unheard of for classes in public schools to be interrupted by lockdowns due to nearby shootings.

On a recent Tuesday evening, however, the small but cozy Project Create studio hummed with the quiet activity and conversation of 12 excited children and youth. Melissa Muttiah, a teaching artist with Project Create, patiently reviewed the “studio rules for behavior” created by the students earlier in the year, reminding them that the rules ensure that the studio remains a safe space for everyone. Muttiah demonstrated the process of making an accordion-style book out of card stock, origami paper, ribbons, and glue sticks. The project is not difficult, but it does have a number of specific steps, and the children were eager and attentive despite the wide range of grades represented, from elementary through high school.

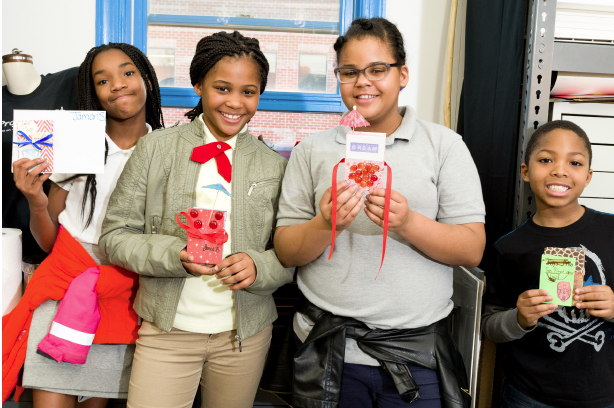

At the Project Create home studio pictured here, professional artists provide therapeutic arts programming to children and youth from Washington, DC’s poorest neighborhoods.

The students were attending Project Create that evening through a partnership with FAN DC, a mentoring organization for children and youth in foster care. (FAN is an acronym for Fihankra Akoma Ntoaso, which means “safe house, linked hearts” in the West African language of Akan.) FAN mentors picked up the students at their individual homes or schools for after-school programming that includes an art class with Project Create. As the class progressed, Muttiah, along with several assistants, circulated around the room repeating instructions, giving more demonstrations of the folding techniques required, and offering quiet encouragement and praise. By the end of the evening’s class, students were smiling with pride at the blank books they had created and personalized. They would now take their books home to fill as they liked, perhaps using them as sketchbooks or journals.

This class is one example of the many classes Project Create offers. In fact, the amount of programming Project Create provides, in the number of locations it serves, is remarkably comprehensive. The week’s schedule includes 15 classes offered through program partners in 13 different locations that include family shelters, long-term and transitional housing for families and youth, and Section 8 housing developments. Children and youth living in these locations have the opportunity to take classes such as visual art, spoken word and street art, mixed media collage, photography, hip-hop dance, and fashion.

“Broadly and anecdotally, what we see is that kids in shelters have very few opportunities to engage in artistic endeavors and self-exploration. Project Create can reach and engage those children, and keep them active in their community. … We are only kids once.”

—Maggie Riden, DC Alliance of Youth Advocates

This jam-packed schedule does not even include classes held in the Project Create studio, which offers painting and collage, digital design, dance, drop-in art time, teen studio (a variety of art opportunities for ages 13 and up), and Capoeira Angola (a Brazilian martial art). More arts opportunities through Project Create include documentary film, songwriting, music production, and, in partnership with the Anacostia Playhouse, theater improvisation. Children and youth interested in studying fine art have the opportunity to receive individual instruction. Project Create classes are free, offered after school and during the summer break, and designed for children and youth whose families are homeless and/or living in poverty. As impressive as it is, the breadth of Project Create’s arts programming and the depth of its commitment to youth development are only part of the reason that the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness honored Project Create with the 2016 Beyond Housing award at the Beyond Housing conference in New York in January.

Maggie Riden, executive director of the DC Alliance of Youth Advocates (DCAYA), nominated Project Create for the Beyond Housing award. Riden has worked closely with Project Create in the past through DCAYA, which is a coalition of 130 youth development organizations dedicated to supporting area youth, making sure they have access to the opportunities they need to thrive, driving research in youth development, and finding funding to promote high-quality projects.

As students make art, they are also building relationships with caring adults and learning life skills like collaboration, teamwork, perseverance, and problem solving. Such skills help create resiliency in students, who often face many stressful challenges as a result of poverty and homelessness.

“Project Create is an incredible program,” says Riden. “Broadly and anecdotally, what we see is that kids in shelters have very few opportunities to engage in artistic endeavors and self-exploration. Project Create can reach and engage those children, and keep them active in their community. Project Create also helps to make a shelter a place where kids can be kids, physically and emotionally. … It is such a unique time. We are only kids once.”

“We are lucky because DC is so rich in the arts, arts educators, and artists,” says Project Create Executive Director Christie Walser. “We draw from our local community to engage teachers in all disciplines, so we can offer a huge range of visual, performance, and digital media arts.”

The organization was created in 1994 by pastor and community activist John Wimberly who saw a need for positive, community-building activities focused on youth. At the same time, the public school system was cutting funding to arts programs. Using creative arts as a tool for youth development provided a way for Wimberly to support area youth while providing quality arts instruction. Wimberly started with one after-school arts program for children attending Thaddeus Stevens Elementary School. The organization grew over time both in locations and in programming. In 2016, Walser expects Project Create will serve over 500 children and youth, ranging from ages 5 to 24, living primarily in DC Wards 7 and 8.

Art projects created by the children and youth participating in Project Create’s extensive programming are on display at the organization’s home studio in the Anacostia neighborhood of Washington, DC.

In addition to its classes, Project Create coordinates arts enrichment field trips (e.g., theater and museum visits), holds community art events for families several times during the year, and puts on exhibitions and performances for the community. A board-certified art therapist develops the programming which is delivered by experienced, trained artists who are supported by teacher assistants or student assistants. Most important, as students make art, they are also building relationships with caring adults and learning life skills like collaboration, teamwork, perseverance, and problem solving. Such skills help create resiliency in students who often face many stressful challenges as a result of poverty and homelessness. The quality of resiliency is an important predictor of future positive life outcomes for children and youth, which is why many youth development organizations such as Project Create strive to develop it in the populations they serve.

According to Project Create, 80 percent of its programming serves children and youth experiencing homelessness, and 20 percent takes place in partnership with out-of-school-time programs in high poverty neighborhoods. Most classes take place “East of the Anacostia,” meaning the neighborhoods of Wards 7 and 8 located east of the Anacostia River. The poverty rates there are extremely high—40 percent and 50 percent, respectively, of households are living below the poverty line. (The federal poverty line is defined as a household income of $24,000 per year for a family of four.)

Through partnerships with housing and social service organizations like Community of Hope and Sasha Bruce Youthwork, Project Create delivers arts classes on-site in transitional, emergency, and long-term affordable housing locations. The classes are a welcome, fun, and safe place for students who are dealing with serious challenges in their lives. The program partners are grateful for the service Project Create provides children in the community. “The teachers have great relationships with the kids, and the kids look forward to it,” says Carla Turnage, program director at DC’s Community of Hope. “It gives them an opportunity to do something fun, and it also encourages them to try new things outside of class.”

Project Create classes like the one shown in this photo aid in the development of life skills such as collaboration, teamwork, and problem solving.

Project Create’s studio in Anacostia opened in 2015 and helps program staff maintain a relationship with students they originally encountered in temporary housing situations. Many students take the local bus line and/or the DC Metro (the local train) to visit the studio, and some students have been involved with Project Create for as many as ten years.

“Our families are transitional,” says Walser. “They move around, and in and out of homelessness. Sometimes they move from transitional housing to long-term housing to supportive housing. There is a lot of flux, and we were finding that we were establishing relationships with students, but if the family moved or the partnership changed, then we were losing the relationship with those kids. With our new home studio, those kids are coming to us. Basically no matter where they are, if there is a relationship, they can find us. We have a lot of relationships start through housing providers, and then families can continue with us at the studio, so that has been a great outcome. We host classes six days a week, so at any one time, we have around 24 to 25 classes happening throughout the city.”

“Art therapy really focuses on the process and making sure that feelings and emotions and things can be expressed using art materials. … Art therapy works really well with folks experiencing trauma.”

—Lindsey Vance,

art therapist and senior program manager at Project Create

Eric, age 17, is one such student in the DC public school system. While attending class at Project Create, Eric had to move from his family home into a group home for boys because of a family conflict. After developing close ties with Project Create staff, he maintained his relationship with them even after moving. Most days after school he visits Project Create. Sometimes he participates in programming (such as a Teen Night field trip), other times he works as a student assistant in one of the art classes for younger children, and sometimes he just goes by the studio to say hello and touch base with Christie Walser, with whom he has become close. Eric enjoys the art classes—his personal highlights include using spray paint in a street art class, learning to sew by hand and with a machine, and using a 3-D printer. Every Monday evening he attends the teen open studio. “We can come in and work on an art project,” he says, describing the teen studio, “or just chill it.”

Project Create uses art classes like this to build self-awareness in their students, creating well-rounded individuals and nurturing them from the inside out.

Eric has developed friendships with other students at the studio and a close mentoring relationship with Walser. When Eric recently visited the studio, Walser asked him how he was feeling, encouraged him to snag a snack from the studio kitchen when he mentioned being hungry, and reminded him that he needs to fill out his application for DC’s Summer Youth Employment Program, which should allow him to continue working at Project Create and be paid through the city. Sometimes Eric even calls Walser “Ma.”

“I knew she was a person I could talk to,” says Eric about Walser, who has been a stable presence among recent major changes in Eric’s life. “I could trust her. She is always there for me.” When talking about the many challenges Project Create students like Eric face, Walser says, “I admire our kids. They are so strong, so resilient, and so creative.”

“You get to express yourself.

And no one judges you.”

—Naimka, Project Create student

Part of Project Create’s uniqueness is its emphasis on arts instruction that is also therapeutic. But what exactly is therapeutic art, or art therapy, as it is also known? Lindsey Vance, art therapist and senior program manager at Project Create, readily explains the concept. “Rather than having just an art class, where you are learning about how to create a certain product,” says Vance, “art therapy really focuses on the process and making sure that feelings and emotions and things can be expressed using art materials. My focus is less on what the children and students come here to create, and more on the process and what they are going through. Art therapy works really well with folks experiencing trauma.”

Seventeen-year-old Eric embraces Executive Director Christie Walser, who has remained a constant in his life. He visits Project Create most days to participate in programming as well as to work as a student assistant in one of the classes.

“It may just look like a regular art class on the surface,” continues Vance, meaning that Project Create art teachers discuss techniques and students follow steps just as in any other class. “We have teaching artists who give specific directives for assignments.” She discusses a painting and collage class. “But we are really focusing on creating meaningful ways to create images and collages about the self. We are trying to cultivate self-awareness in our students so that we can create a well-rounded individual, and kind of nurture and grow our students from the inside out. Whether it is theater, or dance and movement, we are coming at art from a perspective where it is not about just learning skills, it is also learning about yourself and how you can apply these skills.”

Clearly, Project Create is making great headway in its mission to create art, to create opportunity, and to create community. Naimka, a ten-year-old student, recently visited the drop-in art session at the home studio. She greeted staff cheerfully, turned on some music, and settled in to practice digital art. She created colorful, abstract designs on a computer while chatting comfortably with Walser and the art teachers and assistants. Asked why she enjoys attending Project Create, Naimka says simply, “You get to express yourself. And no one judges you.”

Project Create will serve over 500 children and youth in 2016. A few of those students proudly showcase their completed art projects.

Resources

Project Create http://projectcreatedc.org Washington, DC ■ Fihankra Akoma Ntoaso http://www.fan-dc.org Washington, DC ■ DC Alliance of Youth Advocates http://www.dc-aya.org Washington, DC ■ Community of Hope https://www.communityofhopedc.org Washington, DC.

Download this article here.

Download this article here.

CATCHing Signs of Trauma: North Carolina Program Connects Homeless Children to Mental Health Services

by Mari Rich

Like most nine-year-olds, Monteece is a ball of energy, bouncing from school to soccer practice to acting class. And like most nine-year-olds, he sometimes procrastinates at homework time. “All I have to do, though, is remind him what a good time he had at engineering camp over the summer and how much he learned,” his mother, DeAnna (her name has been changed for this article), says, “and I emphasize that he has to keep his grades up if he wants to go back this year.”

DeAnna explains that Monteece’s impressive list of extracurricular activities and newfound ambition to become an engineer seemed highly unlikely not too long ago. “I was in an abusive relationship for several years,” the North Carolina resident recalls. “I finally left with Monteece and my two other children, Shone and DeNadya, and we ended up [spending] three months at a domestic violence shelter in Wake County. It turned out to be one of the places affiliated with the CATCH program, so suddenly I had access to resources and services I might never have known about before and certainly could not have afforded in any case.”

Project CATCH nurtures the health, well-being, and success of children experiencing homelessness. One of the parenting programs Project CATCH offers, Raising a Thinking Child, is focused on nurturing a child’s problem-solving abilities—an essential skill for all children.

Project CATCH (Community Action Targeting Children Who Are Homeless) is a Raleigh, North Carolina-based program whose mission is to ensure that families experiencing homelessness in Wake County have access to a coordinated system of care that nurtures the health, well-being, and success of their children. “Often, when families enter the shelter system, their number-one priority is employment and housing,” says Jennifer Tisdale, the coordinator of Project CATCH. “Obviously that is a pressing concern, but there are so many other issues impacting them. Prior to CATCH, we found that because of a combination of the drive to place the entire family in safe, stable housing and low staffing resources, the mental health and developmental needs of the youngest children—who had often suffered repeated upheaval and trauma—were not being effectively addressed.”

Recognizing the Problem

CATCH had its genesis eight years ago when frontline personnel at the Salvation Army of Wake County realized that the children in their shelter were experiencing noticeable difficulties; many were exhibiting age-inappropriate behaviors, an inability to focus, feelings of frustration and anger, and other such problems. The organization hired a case manager to conduct assessments and discovered, as they had suspected, that the social-emotional adjustment and development of their youngest residents was cause for concern. They subsequently approached the Young Child Mental Health Collaborative (YCMHC), a group of local professionals from various sectors. During a series of monthly meetings between shelter personnel and YCMHC members, they concluded that although a wealth of childhood resources and experts existed in Wake County, homeless families rarely benefited from them for a variety of reasons. Oftentimes, shelter staff did not access community resources because they had not been trained to recognize the sometimes-subtle signs of trauma or developmental delay. Even when they became aware of a child in need of services, there was no comprehensive, shared source of accurate information related to what was available in the region. Adding to the problem, there was little commitment among the available family- and child-serving agencies to prioritize those experiencing homelessness—often because personnel were entirely unaware of the scope of the problem right in their own communities. (In Wake County alone there are an estimated 5,000 children under the age of 18 experiencing homelessness.)It was obvious that a comprehensive, all-hands-on-deck plan to address the general well-being of homeless children in Wake County was desperately needed, and thus the idea for CATCH was born.

Since its inception, more than 1,700 referrals and connections to Wake County’s existing services have been provided to children and their parents.

Implementing the Solution

Project CATCH was spearheaded by the Salvation Army, the YCMHC, the child-advocacy group Wake County SmartStart, and the philanthropic John Rex Endowment. Almost a dozen Wake County shelters, many school social workers, and more than 20 community providers now refer people to CATCH and deliver services to CATCH clients. CATCH offers case management and referrals to services that address the specific needs of the children in their care. Since its inception, more than 1,700 referrals and connections to Wake County’s existing services have been provided to children and their parents. (CATCH receives, on average, 40 referrals from partners a month.)

Professor Mary Haskett, who teaches psychology at North Carolina State University in Raleigh and directs the school’s Family Studies Research Team, is an advisory board member of Project CATCH who has been involved in the program since the beginning. She explains that the program seeks to intervene holistically. “Children develop within families,” she says. “Those families are embedded in shelters, and the shelters are part of communities. We want to operate on all of those levels in order to achieve the best possible results.”

Project CATCH works closely with children who enter shelter to identify any developmental delays and connect them to services such as therapy.

From the start, one of CATCH’s priorities has been to screen young shelter residents to assess their developmental functioning and make referrals to appropriate services. When a partner refers a family to CATCH, an intake worker asks parents for permission to screen the children. If the parents agree, a CATCH case manager schedules a psychosocial interview, followed by a Brigance Early Childhood Screen, a widely used test that assesses development and identifies delays. Additionally, parents are asked to complete questionnaires about their children’s social and emotional behaviors, and CATCH workers also collect medical and school records, when available. Based on the overall findings, they make recommendations for educational and mental-health interventions, such as academic remediation or therapy, and even provide transportation to therapeutic appointments. Jennifer Santitoro, the associate director of InterAct, a Wake County agency that provides support services to survivors of domestic violence and rape or sexual assault, praises the speed and responsiveness of the CATCH team. “Within 24 to 48 hours of our call, a case manager visits,” she says. “That is especially important because clients stay at our residential shelter for just eight weeks, and we need to do as much for them in that relatively short period of time as possible.”

Project CATCH has made impressive strides—especially considering that only two paid employees, Jennifer Tisdale and Taylor Ward, run the program.

In a recent study conducted by Haskett, Tisdale, and their colleagues, almost one-quarter of the children screened were found to be in need of mental-health services. Haskett explains that while many of the children experiencing homelessness are remarkably resilient, by the age of 12, more than 80 percent of them have been exposed to at least one serious violent incident, and almost one-quarter have—like Monteece, Shone, and DeNadya—witnessed instances of domestic abuse. Others have been parented by those suffering from addictions or depression, and some have been the target of maltreatment or neglect. Entering a shelter is no guarantee that a child will lead a stress-free existence, either. Lack of privacy, precious belongings placed in storage (and often lost completely due to an inability to pay the storage fees), friends left behind, and families occasionally torn apart due to restrictions regarding males in the shelter—all of these factors create anxiety and impede positive family interactions. “Isolated from their former social circles and with their routines disrupted, children in shelters are at undeniably greater risk for developmental delays and mental health issues,” Haskett says.

“Children develop within families. Those families are embedded in shelters, and the shelters are part of communities. We want to operate on all of those levels in order to achieve the best possible results.”

—Mary Haskett, advisory board member of Project CATCH

In addition to the screenings, CATCH helps meet the mental health needs of shelter residents by training personnel in “trauma-informed” practices. Traumatic experiences, as neuroscientists have shown, can adversely affect the developing brain of a child by altering the formation of important neural pathways, leading to attachment disorders, decreased cognitive abilities, oppositional behavior, and emotional issues. According to the National Council for Behavioral Health, trauma-informed providers must recognize that trauma of any type “can have broad and penetrating effects on a client’s personhood” and should strive to create soothing physical environments and to convey attitudes of dignity, respect, and personal empowerment. (Because shelter personnel are apt to experience their own stress and compassion fatigue—a type of emotional exhaustion brought on by the rigors of caring on a constant basis for those in need—CATCH managers encourage them to practice selfcare strategies such as yoga and meditation.)

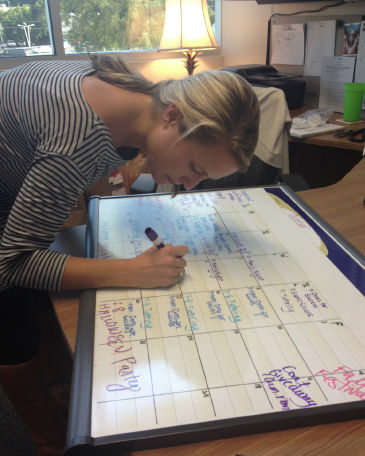

Taylor Ward, Project CATCH’s outreach case manager, schedules the weekly activities and programs that emphasize positive parent-child relationships.

The Importance of Play and Interaction

It takes more than healthy, well-developed neural networks to ensure that a child will thrive, and the CATCH program rigorously addresses another important factor: the parent-child relationship. DeAnna, who works full time at the Xerox Corporation and is currently studying for an undergraduate degree in accounting, has taken part in many of the parenting classes offered through CATCH. “I have picked up good strategies for initiating discussions with my kids, which is very important considering all they have been through, and I have also learned about the importance of play and interaction,” she says. “I know that I am a stronger, more effective parent now.”

Among the programs open at various times to CATCH participants are Raising a Thinking Child, a six- to eight-week course designed to help parents communicate in a way that nurtures a child’s interpersonal, cognitive problem-solving skills; the Triple P—Positive Parenting Program, designed to prevent and treat behavioral and emotional problems in children and to equip parents with the skills they need to manage family issues independently; Physical and Emotional Awareness for Children Who Are Homeless (PEACH), a 16-session curriculum that teaches young children about good nutrition, physical activity, and how to deal with the emotional stress of being homeless; Theraplay, an intervention based on natural patterns of playful, healthy interaction between parents and children; and Circle of Parents, a self-help support group.

“I have picked up good strategies for initiating discussions with my kids, which is very important considering all they have been through, and I have also learned about the importance of play and interaction. I know that I am a stronger, more effective parent now.”

—DeAnna, Project CATCH participant

Jennifer Tisdale and her colleagues have seen firsthand the power of parenting classes. “During the first session of one program we ran, many of the participants arrived late and were visibly reluctant, and there was just one mother really interacting with her toddler,” a case manager recalls. “Other toddlers were leaving their own mothers to go over to her to play and cuddle. It was not that the other women were bad mothers; it is just that most had never been played with or cuddled themselves as youngsters, so they simply did not realize what they should be doing. During the program they learned games they could play with their children, stories they could tell, and other ways to engage, and by the end, it was a pleasure to watch the improved relationship between each mother and child pair.”

Bringing Partners to the Table

The children of Wake County have a plethora of enrichment activities available to them—from museums to sports programming to special-interest camps—and the founders of the CATCH program saw no reason that children experiencing homelessness should not enjoy those very same things. “We wanted to bring good people from throughout the community to the table,” Haskett says. “And generally, it was just a matter of asking. Once people are made aware of the need, they want to help.” So now, for example, the North Carolina State College of Engineering welcomes CATCH kids like DeAnna’s son Monteece to week-long camp programs during which they design extreme waterslides, solar-powered cities, heart valves, and more. The Marbles Kids Museum, a popular Raleigh institution, offers CATCH families free annual memberships, enabling children to participate in fun and educational experiences they may not otherwise have, and hosts regular parent workshops that all are encouraged to attend. Michelle Mozingo, the district’s McKinney-Vento liaison, who is charged with ensuring that homeless students enroll in school and have full and equal opportunity to succeed in school, has helped organize workshops at the museum. She says, “We are able to speak with families regarding preparing their child for school, discuss any concerns a parent may have for a child already in school, and provide materials to educate parents on how they can be more involved in their child’s education. It allows me to reach more families and be a more effective liaison.”

“All of the groups that work with us are aware of our clients’ issues and are willing to address them in creative ways,” Haskett says. “The number of partnerships we have forged has grown steadily, and fostering those connections can make a tremendous impact on the lives of the children.”

“Without CATCH, children would be at risk of falling through the cracks, the community would be unaware of the issue of family homelessness, and children’s needs would be largely ignored or unidentified. CATCH clearly goes well beyond housing.”

—Damon Circosta, A.J. Fletcher Foundation

Susan D’Amico, who oversees the engineering camp at North Carolina State, believes that the program not only made a tremendous impact on Monteece, who took to the curriculum like “a fish to water,” but that his participation will, in turn, allow him to impact the world. “It is great when engineering catches the imagination of kids that young,” she says. “Engineers work to solve important problems, like ensuring access to clean water or developing ways to generate green energy. They help make the world better, and now Monteece realizes he can contribute to that.”

Going Well Beyond Housing

Some of CATCH’s impact can be measured by the numbers. Since mid-2015 CATCH has completed more than 500 psychosocial, developmental, and socio-emotional screenings (54 percent of all children referred); provided more than 650 clothing vouchers and almost as many food vouchers; given out almost 100 furniture vouchers; made more than 70 referrals to a partner agency that provides diapers to low-income Wake County families; connected 50 kids to after-school programs and an equal number to child care services; helped almost 200 obtain health care and mental-health services; provided 76 housing referrals and resources to families; and contributed to 10 families being permanently housed through a new community collaboration led by CATCH that targets families who have been placed in hotels as a stopgap measure.

Those numbers are even more impressive when you consider that the CATCH program is run by just two paid employees, Tisdale and Outreach Case Manager Taylor Ward. “It is a matter of marshaling the resources already in place,” Haskett says. “You just have to get together at a grassroots level, see which elements are missing, and then reach out to someone who can provide those elements. It is a model that could be easily replicated anywhere in the country, and we are happy to advise anyone ready to do that.”

Project CATCH offers parenting classes that emphasize the importance of play and interaction between parents and children.

There may soon be organizations lined up for that advice, as word of CATCH spreads. The project recently won the 2016 Beyond Housing award from the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, which honors people and organizations whose work exemplifies the idea that homelessness is much more than a housing issue. Damon Circosta, the executive director and vice president of the A.J. Fletcher Foundation, which has provided funding for CATCH, nominated the project for the honor. “CATCH is a unique program that accomplishes a lot with a little,” he says. “Without CATCH, children would be at risk of falling through the cracks, the community would be unaware of the issue of family homelessness, and children’s needs would be largely ignored or unidentified. CATCH clearly goes well beyond housing.”

DeAnna concurs. “I consider everyone involved in the program to be a blessing, and I will never stop being grateful to them,” she says. “They very literally changed our lives and created a future for my children. We are out of the shelter and in an apartment now. Shone is thriving because of counseling he received through CATCH. Monteece has so much confidence because of his acting classes and a new career goal because of his engineering camp. Who knows where any of us would be without CATCH?”

Resources

Project CATCH http://www.salvationarmycarolinas.org/wakecounty/programs/social-ministries/project-catch/ Raleigh, NC ■ Wake County SmartStart http://www.wakesmartstart.org Raleigh, NC ■ John Rex Endowment http://www.rexendowment.org Raleigh, NC ■ North Carolina State University https://www.ncsu.edu ■ Raleigh, NC ν National Council for Behavioral Health http://www.thenationalcouncil.org Washington, DC ■ InterAct http://interactofwake.org Raleigh, NC ■ A.J. Fletcher Foundation http://ajf.org Raleigh, NC.

Download this article here.

Download this article here.

SafeCare: Strengthening Families in Shelter through Parenting Education

by Anita Bushell

“How was school?” asks Adebukola Adeniyi, as three-year-old December enters her family’s transitional apartment (a one bedroom unit with a kitchen, bathroom, and beds for each family member) at Flagstone Family Center, a family shelter in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn that houses more than 150 families. December’s mother, Crystal, is participating in SafeCare, a parent training program offered by the center. Adeniyi is the SafeCare-trained parenting specialist working with Crystal and her family.

The goal of SafeCare is to teach effective parenting skills to families who are at risk for, or have histories of, maltreating young children (from birth through age five). At-risk families include young parents; parents with a history of depression or other mental health problems, substance abuse, or intellectual disabilities; foster parents; parents recently released from incarceration; parents with a history of domestic violence or intimate partner violence; and—as in the case of Crystal and December’s family—families experiencing homelessness.

Adebukola Adeniyi, a SafeCare parenting specialist, works with three-year-old December and her mother Crystal on SafeCare’s parent-child interaction module, which teaches parents to provide engaging and stimulating activities, increases positive interactions between parents and children, and prevents troublesome child behavior.

SafeCare operates in 22 states and six countries and is typically implemented on an individual basis in a family’s home. CAMBA, the nonprofit agency that operates Flagstone Family Center and other emergency, transitional, and permanent housing, as well as offers service-oriented programming to New Yorkers in need, is among the first to adapt the program to a shelter setting. CAMBA has used the SafeCare model for about two years with more than 170 families enrolled in its foster care prevention services, only some of which were living in shelter. In September 2015, with support from New York City Council member Stephen Levin’s office, the agency began offering SafeCare to every family living at Flagstone.

By working within the shelter system, SafeCare trainers provide assistance where it is needed most. Parents in shelters can often feel like they are “isolated, alone, and have no one to talk to,” says Gabrielle McCollins, program supervisor for SafeCare Family Services at CAMBA. McCollins is committed to providing more than just accommodations to homeless families. “It is important to embed services into the shelter system,” she says, “due to families facing many stressors, including histories of trauma, homelessness, domestic violence, and abuse. The SafeCare program … assists families through crisis situations and links families to community-based services and organizations. Embedding services into the shelter system decreases stressors and improves children’s behaviors.”

Adeniyi and her colleagues provide parental support as well as create a sense of community. “I hear that you are frustrated,” Adeniyi will tell parents after they report having a bad day. She counsels them to take “one problem at a time” and asks, “What two things can we do to minimize the stress?”

SafeCare training typically lasts between four and six months and is implemented on a weekly basis. When a SafeCare trainer visits a family, the trainer begins with an assessment to investigate if the home is safe, to make sure the children are healthy, and to determine the strength of the bond between the parents and children.

The next step is to improve the parent’s skills in four areas, or modules: health (i.e., training parents to prevent and/or identify a child’s illness and seek treatment); home safety (i.e., eliminating health and safety hazards in the home); parent-infant/child interactions (i.e., teaching parents to provide engaging and stimulating activities, increase positive interactions with their children, and prevent troublesome child behavior); and problem solving and communication (i.e., helping parents learn how to work through the stress they may face in a healthy manner).

SafeCare builds upon the skills parents already have while giving them additional resources and practice. “The main benefit[s] of SafeCare,” says Janee Harvey, a licensed social worker who implemented SafeCare in CAMBA’s foster care prevention services in 2013, are that “it is a behavior-based training curriculum that uses parents’ strengths while encouraging them to use different and more effective approaches to keeping their kids safe, healthy, and responding to their instructions.”

Adeniyi is currently working on the parent-child interaction module with Crystal and comes armed with activities, as well as rewards, to engage December, who is the focus of today’s training. “For two minutes we are going to do an activity; you can choose.” “Color!” December responds. Setting a kitchen timer for two minutes, Adeniyi colors with December, interacting and reminding her that she will get a reward if she colors until the timer goes off. When it does, December gets a high five and the choice of one piece of candy from Adeniyi’s jar.

To ensure the successful learning of each module, trainers utilize what is known as Safe-Care 4 (Explain, Model, Practice, Feedback). In this process, the trainer describes a behavior and its rationale, models the behavior, has the parent practice the behavior, and, finally, gives constructive criticism. When all the training modules have been completed, the parent fills out a questionnaire to provide feedback on the process. This format is grounded in evidence-based research and established social learning theory, which posits that behavior can be learned by observing others.

Following this model, it is now Crystal’s turn to practice the behavior. December chooses to work on a puzzle. “Should we do it together?” Crystal asks. The timer is reset. Sitting down on the floor, December and her one-year-old brother, Logan, decide to work the puzzle with their mother. “Purple goes with purple,” Crystal tells December. “Match the orange. … Good job!” she tells her when she matches a piece. “You see any other colors that go together?” she asks.

After the timer rings everyone sings the “clean up” song, and Adeniyi reflects on what she observed, praising Crystal for giving December a choice, sitting on the floor with both children, and encouraging them to clean up. “You guys did a good job! The more practice we do, the more comfortable it will be, like wearing a shirt.”

SafeCare trainers report a marked improvement in parent interactions with children and they feel pride in seeing the effect the curriculum has on the families they coach. “We are a team,” Adeniyi says about her bond with Crystal.

Crystal has noticed how beneficial SafeCare has been to her family. “I’m interacting better, talking more, and everything. It is a good program. It can help a lot of parents,” she says.

Studies show that this is true. One ten-year study found that maltreatment of children age five and under was reduced by 26 percent among families who received SafeCare training in Oklahoma. “As the longest-term evaluation to date of a home visiting program in a child welfare system, these findings demonstrate the impact of SafeCare when implemented broadly,” says John R. Lutzker, director of the Mark Chaffin Center for Healthy Development, professor of public health, and associate dean for faculty development at Georgia State University in Atlanta. In another study, the number of home hazards was reduced by 78 percent, and there was an 84 percent increase in the use of the parenting skills taught.

In 2007, the National SafeCare Training and Research Center (NSTRC) was founded with funds from, among others, the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, to assist in the implementation of SafeCare across the country. The center’s goal is to expand SafeCare nationally and internationally, while continuing to refine the training program and raise awareness of the need for evidence-based practice. Furthering this goal, Jenelle Shanley, associate director of training at NSTRC, and Janee Harvey presented the SafeCare program and information about its use in the shelter setting at the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness 2016 Beyond Housing conference in New York in January.

Adebukola Adeniyi, pictured with Crystal, her daughter December, son Logan, and husband Miguel, works to provide support and a sense of community for Crystal and her family.

The timing for providing parents in shelter with these tools could not be better. Child Welfare Watch, a publication from the New School’s Center for New York City Affairs, recently noted in its Winter 2015 report that in New York City alone, a staggering 10,700 children in shelter were found to be under the age of five. This figure is up 60 percent since 2006.

These numbers are deeply troubling when considering that young children need a healthy, stable environment to develop and that homelessness is both destabilizing and traumatic; being separated from loved ones and uprooted from their communities during relocation can result in developmental delays.

The Child Welfare Watch report notes, however, that “researchers have discovered a powerful antidote to the toxic effects of chronic stress: When children are raised by particularly responsive or nurturing parents, their cortisol patterns and brain function are far more likely to be healthy, even if they live in the midst of upheaval and chaos.”

SafeCare provides parents with the concrete skills to give their kids this nurturing care and relieve the effects of homelessness on their families. “SafeCare impresses upon parents that you are the baby’s first teacher, and we are promoting touch, which we know facilitates bonding,” says Harvey. By bringing programs such as SafeCare into the shelter, organizations like CAMBA are recognizing that children’s time in shelter can be an opportunity to positively influence their lives.

Resources

CAMBA http://www.camba.org Brooklyn, NY ■ National SafeCare Training and Research Center http://safecare.publichealth.gsu.edu Atlanta, GA ■Child Welfare Information Gateway https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/preventing/programs/homevisit/homevisitprog/safe-care/ Washington, DC ■ Child Welfare Watch http://www.centernyc.org/time-tested New York, NY.

Download this article here.

Download this article here.

On the Record—Diana Bowman: A Conversation on Student Homelessness

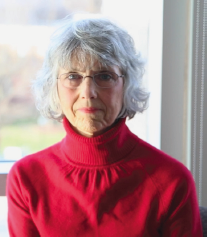

Diana Bowman, former director of the National Center for Homeless Education (NCHE) at SERVE at the University of North Carolina-Greensboro, is our Beyond Housing 2016 honoree “for an individual working at a national level affecting local educational programs for homeless children and youth.” Diana spent her entire career working with and on behalf of homeless students and their families.

She has had a direct impact on thousands of homeless children and their families as well as school districts, service providers, and advocates. As director, Diana worked on everything from developing training tools and tool kits for state coordinators of homeless education, to assisting homeless families directly in getting the help they need, to partnering with people and organizations across the country.

Diana Bowman

UNCENSORED spoke with Diana to learn more about her work, student homelessness, and the challenges homeless families face.

Q. How did you get involved in working with and on behalf of homeless students and their families?

A. I have always loved working with at-risk students. Years ago, I taught writing and reading classes at a small college in a rural area to freshmen who, for the most part, came from impoverished backgrounds and were the first in their generation to attend college. I loved their tenaciousness and practical perspectives. Some years later, at a time of transition in my life, I attended an annual conference of the National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth [NAEHCY], and hearing the stories of challenge and triumph and seeing an army of people committed to the success of homeless children and youth, I knew that working in this field was where I wanted to spend my time. And it just so happened that an opportunity at the National Center for Homeless Education [NCHE] came my way, which enabled me to merge my passion and my profession.

Q. What do you see as the greatest achievement of the homeless services and/or education community in terms of serving homeless students during the span of your career? What is your biggest disappointment or challenge that remains?

A. When I first started working at NCHE, there was much inconsistency in the ways homeless children and youth were enrolled and served in schools. With the reauthorization of the McKinney-Vento Act in 2002, every school district was required to appoint a local liaison who would be the key contact for implementing the law and ensuring that homeless children and youth were enrolled and connected to programs and services. Having a designated person in school districts has made a huge difference in implementation and accountability. Years ago, just getting homeless children and youth enrolled in school, particularly when they did not have the required documents, was one of the biggest challenges. Now, the focus is more on ensuring that they attend regularly, participate fully in educational opportunities, and succeed in school.

The most recent data from the U.S. Department of Education indicate that the number of homeless children and youth identified in schools increased by 15 percent over the past three years.*

I think the biggest disappointment and challenge is that the number of homeless families, children, and youth continues to increase. It would be so great if those of us who work in the field were no longer needed because societal and systemic changes ensured that all people had safe and affordable housing. I would take even a slow, steady decline in numbers, but that does not seem to be happening. The most recent data from the U.S. Department of Education indicate that the number of homeless children and youth identified in schools increased by 15 percent over the past three years.1 In the meantime, those who work on behalf of homeless children and youth need to continue to support young people from the cradle to college or career and keep them healthy and in school so that they will be strong, productive, and self-sufficient adults. We also need to advocate for changes in laws and policies that will create the context and environment for their success.

Diana Bowman, former director of the National Center for Homeless Education at SERVE, is the Beyond Housing 2016 honoree for an individual working at a national level affecting local educational programs for homeless children and youth.

Q. Why do you think that family homelessness remains an invisible issue?

A. For years, the focus of homelessness has been on chronically homeless adults, but I think that is shifting. A number of federal, state, and local programs are focusing efforts in communities on families and youth experiencing homelessness. Nevertheless, many communities are not aware that a great number of homeless families are not found in shelters. The U.S. Department of Education data show that in the 2013–2014 school year, 76 percent of homeless students were living in doubled-up situations. Families living doubled up are considered by many not to be precariously housed, yet these families, children, and youth live in stressful situations knowing that they can be on the street at the whim of their hosts and are often isolated from services that can more easily target people who are staying in shelters. The Department of Education data also show that homeless families live in cars, low-rent hotels and motels, and substandard housing, each with significant challenges but often beyond the awareness of the community and beyond the reach of mainstream services.

Q. What is the most frequent need of homeless students that you have heard of directly from the students that would surprise most people?

A. One of the key messages that has stuck in my mind came from a homeless youth who excelled in school. She said, “Do not hold homeless children and youth to lower expectations. If anything, have higher expectations because they have a bigger mountain to climb.” Building on that message, I believe that the role of educators, service providers, and mentors is to provide homeless children and youth with the resources and encouragement to meet those higher expectations. Moreover, we should acknowledge their creativity and resilience—for example, the homeless child who could think of more ways to use scissors than anyone else in her classroom or the homeless youth who folded his clothes and put them under his pillow at night where he slept in a park so that his clothes would look ironed.

Q. Moving forward, what is the biggest challenge that those providing service or advocacy face?

A. I would say keeping up the momentum. My colleagues across the country are an incredibly dedicated group of people who work long hours and struggle to ensure that homeless families, children, and youth get the services they need, both directly and indirectly. It is a really long haul, but we need to look at the progress we have made. The recent reauthorization of the Every Student Succeeds Act strengthens the McKinney-Vento Act and came about from the tireless efforts of national and grassroots advocates, but there is so much more that needs to be done and we need to stay the course.

Q. What have you learned from homeless students and their families?